Consumers increasingly use social media for a variety of consumption-related tasks such as complaining about a brand or sharing purchase experiences. Social media growth represents an opportunity for business based on information sharing, but also complicates the work of marketing managers who need to be ready to deal with current issues in this field. This article highlights eight areas within social media marketing that create difficult challenges for marketing practitioners. Based on practitioner reports and academic findings about online social networks, we preview emerging threats and opportunities derived from changes in consumers’ behavior and from changes in business models as well. In addition to discussing each challenge, we pose research questions for marketing academics in order to inspire broader research and better understanding of this evolving field.

Los consumidores utilizan cada vez con más frecuencia los medios sociales para diversas tareas relativas al consumo, tales como las quejas acerca de una marca, o el intercambio de experiencias sobre compras. El crecimiento de los medios sociales representa una oportunidad de negocio basada en el intercambio de información, aunque también complica el trabajo a los Directores de Marketing, quienes necesitan estar preparados para manejar las cuestiones corrientes en este campo. Este artículo destaca ocho áreas pertenecientes al marketing de los medios sociales, que crean retos difíciles a las personas que se dedican al marketing. Basándonos en los informes de estos últimos, y en los hallazgos académicos en relación a las redes sociales online, prevemos amenazas y oportunidades emergentes derivadas de los cambios de los comportamientos de los consumidores y de los cambios de los modelos de negocio. Además de tratar cada reto, planteamos cuestiones sobre investigación a los académicos de marketing, a fin de inspirar un análisis más amplio y una mejor comprensión de este campo en evolución.

Social media remain in continuous growth and by some accounts have become the main channel for costumers to experience and interact with the world. To help attain their goals, people join general or more specialized networks and search, share, participate, consume and play (Bolton et al., 2013).

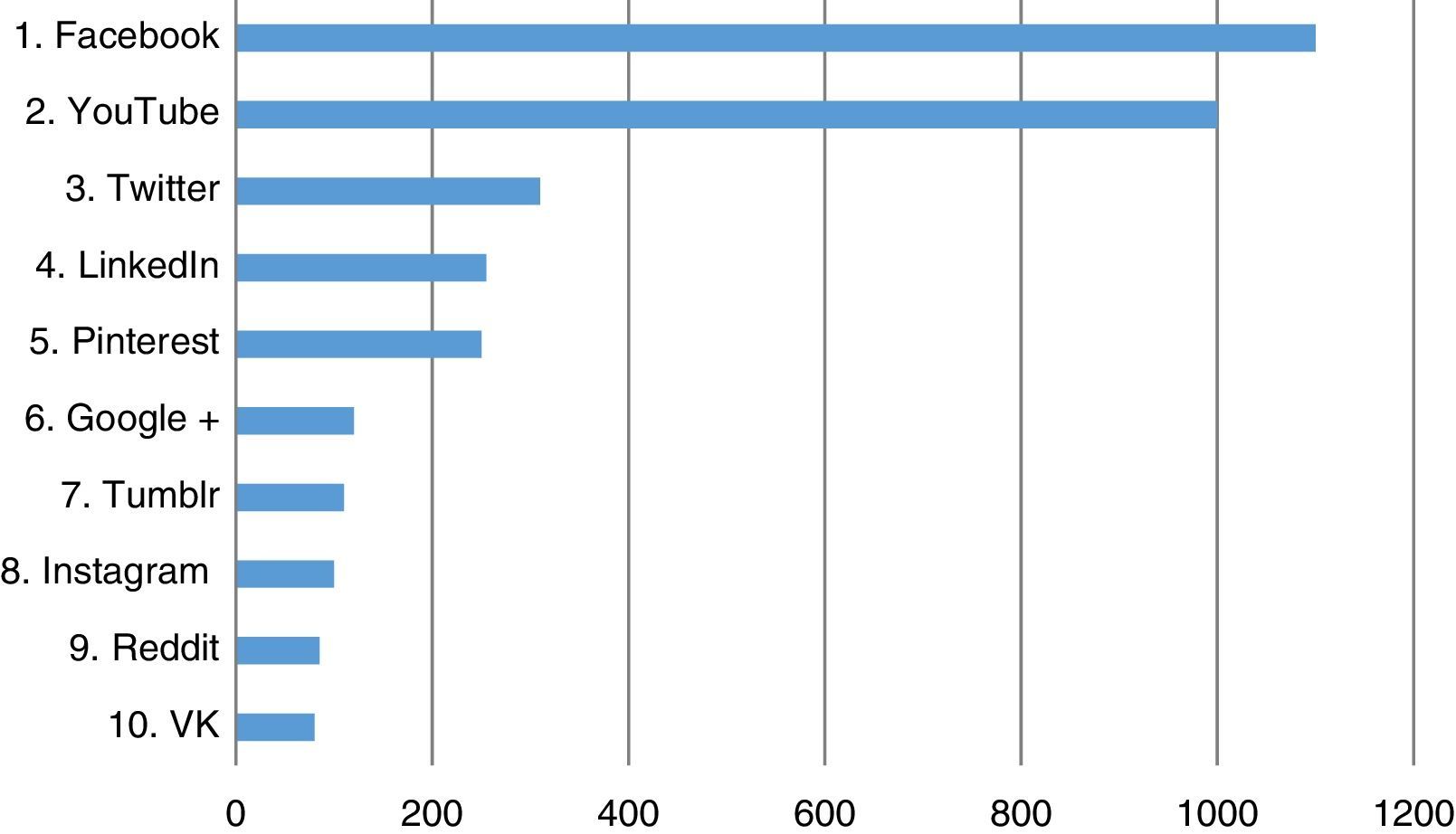

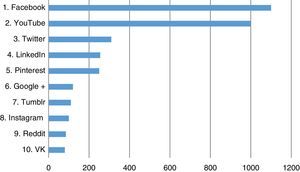

The social media phenomenon could be approached from several perspectives. First, from sociology or anthropology, networks favor interaction between people all around the world. Facebook and YouTube reached more than 1000 million users, as presented in Fig. 1. That means that more than one third of all Internet users in the world, and more than one sixth of the global population, are active members of such networks. Second, from an economic approach, social media have an important value for the firms that own them, although often users do not pay for these services. The recent acquisition of LinkedIn by Microsoft for 26,200 million US$ (more than 102 US$ per user), is an example of the potential value and high rivalry in the social media domain. Corporation's strategic mergers and acquisitions to gather clients, such as Facebook purchase of Instagram and WhatsApp, reveal how important is for companies to lead this digital evolution.

Top 10 social network sites in million users.

Third, from a marketing approach, social media function as a marketspace in which both buyers and sellers exist (Yadav, De Valck, Hennig-Thurau, Hoffman, & Spann, 2013), along with various exchange facilitators (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010), all interacting with each other in complex ways (Hennig-Thurau, Hofacker, & Bloching, 2013). The growth of social media and its information and technology base are thought to represent a great opportunity – and threat – for companies. Currently, firms have the chance to generate innovative business models and to extend customer relationships through social media. However, the rise of social media has also generated a number of difficult challenges for marketing managers.

Previous research has outlined some of these challenges. In an important article, Kaplan and Haenlein (2010) presented a classification of social media based on the level of social media richness (from static blogs to virtual social worlds or games such as Second Life) and self-disclosure (from anonymous content collaborative projects such as Wikipedia to personal presentations in social networking sites such as Facebook). They also suggested that companies choose their social media platforms carefully, develop their own applications when necessary, involve employees, and integrate or align their online activity. They recommended that companies be active, interesting, humble, unprofessional and honest in their social media activity (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010).

From an internal focus, qualitative research has been often employed to describe social media use in organizations as a balance between openness, strategy and management (e.g. Macnamara & Zerfass, 2012). Focusing on managers’ use of social media, Rydén, Ringberg, and Wilke (2015) interviewed managers and identified four kinds of mental models (1) business to customers with a transactional focus to promote and sell, (2) business from customers with an informational focus to listen and learn, (3) business with customers with a relational focus to connect and collaborate, and (4) business for customers with a communal focus to empower and engage customers.

Focusing on Spanish retailers, Lorenzo Romero, Constantinides, and Alarcón del Amo (2013) found that firms demand greater employee abilities to manage online interactive tools. Social media use highly depends on firms’ size, with large companies using social primarily for branding and small companies using it for customer service (Lorenzo Romero et al., 2013).

Taking a broader perspective, in this article we discuss a set of eight social media challenges for marketing managers. These eight challenges are connected to previous research but extend and update the literature by considering the latest academic findings and current marketing practice in industry. A related goal is to provide new research questions for marketing theorists. In this way to we hope to advance the understanding and management of marketing in social media.

Challenge 1: The liquification of the economyMuch of the value produced by the world economy shifted from agriculture to manufacturing in the 19th century, from manufacturing to service in the 20th century, and from service to information in the 21th century (Martin & Midgley, 2003). According to Lambrecht et al. (2014) companies purchase and sell digital information as a product because of its unique combination of traits: Information is (1) not-rival, meaning that consumption does not decrease availability to others, (2) it has near zero marginal cost of production and distribution even over large distances, (3) it has lower cost of search than products sold in offline stores, and (4) reduces transaction costs.

Thus, contrary to goods and services, information is highly liquid, meaning that it flows easily in our era of ubiquitous digital networks. It makes formerly important barriers, like national borders, permeable, complicating the web regulations, for instance in terms of content copyright or international trade licenses. But the border of the firm has become more permeable as well, and sometimes this is problematic. There are frequent database trades or thefts by hackers, with major networks attacks by organized groups or governments (Fernandes, Soares, Gomes, Freire, & Inácio, 2014).

Firm border permeability also enhances the possibilities to establish closer relationships with customers. It is frequently the case that companies allow and motivate customers to create advertising and participate in firm's activities. In general, firms must organize carefully in this new and open environment (Weinberg, de Ruyter, Dellarocas, Buck, & Keeling, 2013). They must also come to grips with the consumer power that this liquification implies (Labrecque, vor dem Esche, Mathwick, Novak, & Hofacker, 2013).

The following research questions arise:

RQ1a: What types of marketing organization fares best under liquefied conditions?

RQ1b: How does marketing strategy change when much of the added value in offerings is derived from information?

RQ1c: Does the marketing function gain within the firm under conditions of permeable firm borders?

RQ1d: Does the marketing function gain under conditions of increased consumer power?

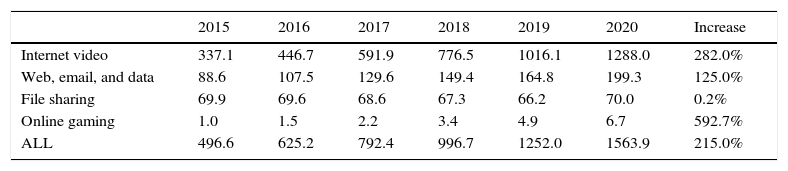

The presence of massive amounts of data and the above mentioned consumer power require that businesses become more nimble, more reactive; we are not in charge any more. Thanks to Internet accessibility, users both demand and provide information continuously, anywhere, anytime and through plenty of devices (Belanche & Casaló, 2015). The popularization of information use by numerous stakeholders leads to an exponential grow of Internet traffic. Table 1 presents the evolution of online information exchange for the period 2015–2020.

Global Internet information traffic by consumer use in Exabytes per year 2015–2020.

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Increase | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internet video | 337.1 | 446.7 | 591.9 | 776.5 | 1016.1 | 1288.0 | 282.0% |

| Web, email, and data | 88.6 | 107.5 | 129.6 | 149.4 | 164.8 | 199.3 | 125.0% |

| File sharing | 69.9 | 69.6 | 68.6 | 67.3 | 66.2 | 70.0 | 0.2% |

| Online gaming | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 4.9 | 6.7 | 592.7% |

| ALL | 496.6 | 625.2 | 792.4 | 996.7 | 1252.0 | 1563.9 | 215.0% |

The English verb used to describe online activity; the verb to navigate; neatly captures the idea that the consumer is no longer passively watching media but is instead in charge of their pre- and post-purchase experience. Although most of user-generated content cannot be controlled, companies may stimulate, drive or monitor brand related content (Araujo, Neijens, & Vliegenthart, 2016).

Big data describes large volumes of high-velocity, complex and variable information assets that demand advanced techniques and technologies to process for enhanced insight and decision making (Gandomi & Haider, 2015). In the presence of such data the role of marketing is devolving toward identifying trigger events that can then be leveraged using one-to-one CRM communication (Hofacker, Malthouse, & Sultan, 2016).

As a result, scholars should follow current trends in the industry and solve the following questions:

RQ2a: Which data events imply the consumer is looking to switch brands?

RQ2b: Can we sense that the consumer is about to buy?

RQ2c: What are the firm antecedents of effective data monitoring?

Marketers have long acknowledged the notion that the customer co-creates value (Vargo & Lusch, 2004). Marketing is a process of performing acts in interaction with the customer, who is an operant and essential resource for the firm. Customer participation may include labor, information, service specification, quality control, knowledge sharing and specific competencies (e.g. design) (Mustak, Jaakkola, & Halinen, 2013). However, in many prototypical new businesses the customer creates nearly all of the value. Examples of this are platform businesses like Facebook, AirBnb, and Uber, companies with modest human resource or other assets. This is consistent with the view of Grönroos and Voima (2013) who emphasize the customer role in value creation since co-creation is necessarily based on the increased value created due to buyer–seller interaction.

We can therefore say that marketing practice is shifting away product management and toward platform management. As such we may find that knowledge about offline platform management will be adaptable to online platforms. In the online setting, technology reliability, interface usability and reduced costs becomes even more crucial (Mikkola & Skjøtt-Larsen, 2006). In this shift toward platforms, key marketing capabilities include encouraging engagement (Hollebeek, Glynn, & Roderick, 2014), and the ability to deal with two-sided markets, discussed below. Active ways to engage customers through social media may comprise using traditional marketing instruments online, such as customer service, customizing the offer, reaching social media influencers and employing customer creativity to innovate together with customers (Constantinides, 2013). Additionally, there is frequently a need to foster user-generated content (Smith, Fischer, & Yongjian, 2012) and to identify influential users (Trusov, Bodapati, & Bucklin, 2010).

In order to move forward on these issues, researchers should further investigate:

RQ3a: What managerial practices encourage consumer creativity?

RQ3b: What practices encourage consumer content creation?

Information and communication technologies represent a disruption in business models and labor markets. Indeed, the Davos World Economic Forum predicts than more than a half of all new jobs in the next 5 years will be related to mobile Internet, cloud technology and big data processing (WEF, 2016); and that 65% of children currently in primary school will work in jobs that do not exist yet.

New business models based on information sharing are spreading globally, as can be seen in the case of multi-side markets. A multi-sided market is one in which each side does not internalize the costs and benefits of the other side (Parker & van Alstyne, 2005). AirBnb (renters and tenants) or Uber (drivers and passengers) are examples of the phenomenon. These companies are rapidly growing their number of clients each year and are challenging the hotel and taxi industries, respectively (Cusumano, 2015). For companies operating in multi-side markets, creating a marketing mix that works for both sides is potentially quite complex. Due to cross-side externalities, sellers prefer to compete with a small number of other sellers but would like to have a large potential buyer base available. Buyers prefer to compete with a small number of other buyers but would like to have a large potential seller base available. Preference differences also extend to price, product, promotion and product. Thus understanding buyer and seller preferences in such two-sided markets seems essential.

More precisely the following questions should be addressed:

RQ4a: What marketing mix variables create tension in that two or more sides have different preferences?

RQ4b: What conceptual models are useful for understanding the tension and optimizing accordingly?

Traditionally marketers have thought of consumer behavior as a problem-solving activity comprised of five steps (Blackwell, Miniard, & Engel, 2001). The traditional steps have long been (1) problem recognition, (2) search, (3) evaluation, (4) purchase, and (5) post-purchase evaluation. At this time the act of consumption is playing out publicly on social media and needs to be explicitly included as a step. This is, perhaps, not surprising. We know that sharing consumption experiences (either positive or negative) creates positive emotion (Kim & Fesenmaier, 2015). Ubiquitous mobile devices and social media facilitate experience sharing behaviors (Shankar et al., 2016); for instance, four out of every five shoppers use mobile in physical stores for consumption related issues (Google, 2013). Think as well of all the photos of restaurant meals that get uploaded onto Facebook or all of the unboxing videos we see on YouTube.

Likewise, post-purchase engagement is becoming sufficiently critical to be considered a step (Hofacker, Malthouse, et al., 2016). For our purposes, we define post-purchase engagement as any public user behavior that creates user-brand interaction or which is directed toward the brand. Post-purchase engagement frequently takes the form of sharing (as in writing a review, for example), and it also has an impact on other consumers’ decisions, specifically when it helps to anticipate the evaluation, and consequences of, purchase (Kladou & Mavragani, 2015; Bagozzi, Belanche, Casaló, & Flavián, 2016).

We may summarize by pointing out that social networks have become a consumption and post-consumption channel, a channel that needs to be integrated with other traditional channels in order to create better management in a multi-channel world (Flavián, Gurrea, & Orús, 2016). Doing this will lead to higher profitability, but not before we answer the following questions:

RQ5a: How can marketing managers leverage public consumption to produce advantage for their brands?

RQ5b: How does the psychology of consumption alter when it becomes public?

Word-of-mouth, now powerfully amplified by digital networks and social media platforms, represents a complex series of sender and receiver interactions (King, Racherla, & Bush, 2014). As a discipline, we have mostly begun to explore the impact of word-of-mouth on the message receiver's purchase intent, but that is just the initial stage of understanding the phenomenon. We might also think about the antecedents and consequences of posting a review on the reviewer. There are a variety of marketing outcomes for both message sender and receiver: memory, knowledge, belief, attitude, and purchase behavior to be understood.

We should also continue to learn the relationship between C2C communication and firms’ performance in terms of sales, revenue and value creation (Pauwels, Aksehirli, & Lackman, 2016). In general, social media can be thought of as a catalyst for the interactive influence between individuals and groups of individuals. No doubt there are complex and interactive effects on these outcomes for word-of-mouth senders and word-of-mouth receivers. In addition research should also focus on the socio-political and economic value of online information sharing (Bechmann & Lomborg, 2013).

The following questions remain yet unresolved:

RQ6a: Does posting a review change the poster's preference hierarchy in some way?

RQ6b: How memorable are product reviews?

RQ6c: What review characteristics lead to higher brand recall?

RQ6d: What is the typical dynamic feedback and causality structure of product reviews?

RQ6e: What factors moderate the typical structure?

The economy is creating more and more currencies, which is to say we are witnessing numerous firm-generated point systems that compete with money for the attention and desire of consumers. Examples of these are cryptocurrencies such as BitCoin, but also more subtle exchange methods involving disclosing customer information (e.g. in exchange for Web access or app use), opt-in advertising formats (Belanche, Flavián, & Pérez-Rueda, 2016), or reciprocity behaviors as in Wikipedia (Schumann, von Wangenheim, & Groene, 2014). We believe traditional CRM will morph into a practice whereby interacting with a firm becomes game-like. Successful using of game elements in a non-gaming context tends to create a hedonic and enjoyable experience, with immediate feedback, clear goals, social comparisons and a state of flow (Hamari, 2013). Gamification is often linked to user engagement in many disciplines such as e-learning, social cause fundraising, and customer loyalty programs. But gamifying firm-customer interaction has been poorly applied and lacks a basis in fundamental psychological insights (Hofacker, de Ruyter, Lurie, Manchanda, & Donaldson, 2016).

The following questions still need answers:

RQ7a: What is the optimal level of difficulty for gamified interaction?

RQ7b: What types of game elements function best in a marketing context?

Digital data do not arrive to us as a simple, clean rectangle of data ready for ANOVA or SEM. Digital data frequently consist of text and images, or even video, as presented above in Table 1. This means that both academics and practitioners need different methodological skill sets than that which we currently teach, as predicted by labor studies (WEF, 2016).

While verbal text mining has become common in the marketing literature (e.g., Schweidel & Moe, 2014), the billions of visual images uploaded are an untapped resource for marketers (Vilnai-Yavetz & Tifferet, 2015). Specialized software has been developed for text data processing using semantic and syntactic knowledge. Automated extracting and understanding of information from pictures and videos will likely be more complex, although important advances are appearing every day; consider for instance face recognition tool in Facebook.

However, social media data also come in new and diverse structural formats, such as graphs or networks. The analysis on the interactions between members of a social network are often useful to identify the different roles played by members, but many other analyses may be performed (Wilson, Sala, Puttaswamy, & Zhao, 2012; Guinalíu & Jordán, 2016). In addition data from several sources may be combined to provide firms with detailed information to better adapt marketing actions to specific users and locations (e.g. geolocation of credit-cards use). As each year goes by, the Internet of Things will begin to add geolocation to the mix of data types that marketers will need to deal with.

RQ8a: Will marketers, or the adherents of another discipline, end up as experts in modeling customer social graphs?

RQ8b: Will marketers end up as the experts for geolocation modeling?

RQ8c: Will marketers end up as the experts for text mining?

RQ8d: Will marketers end up as the experts in video mining?

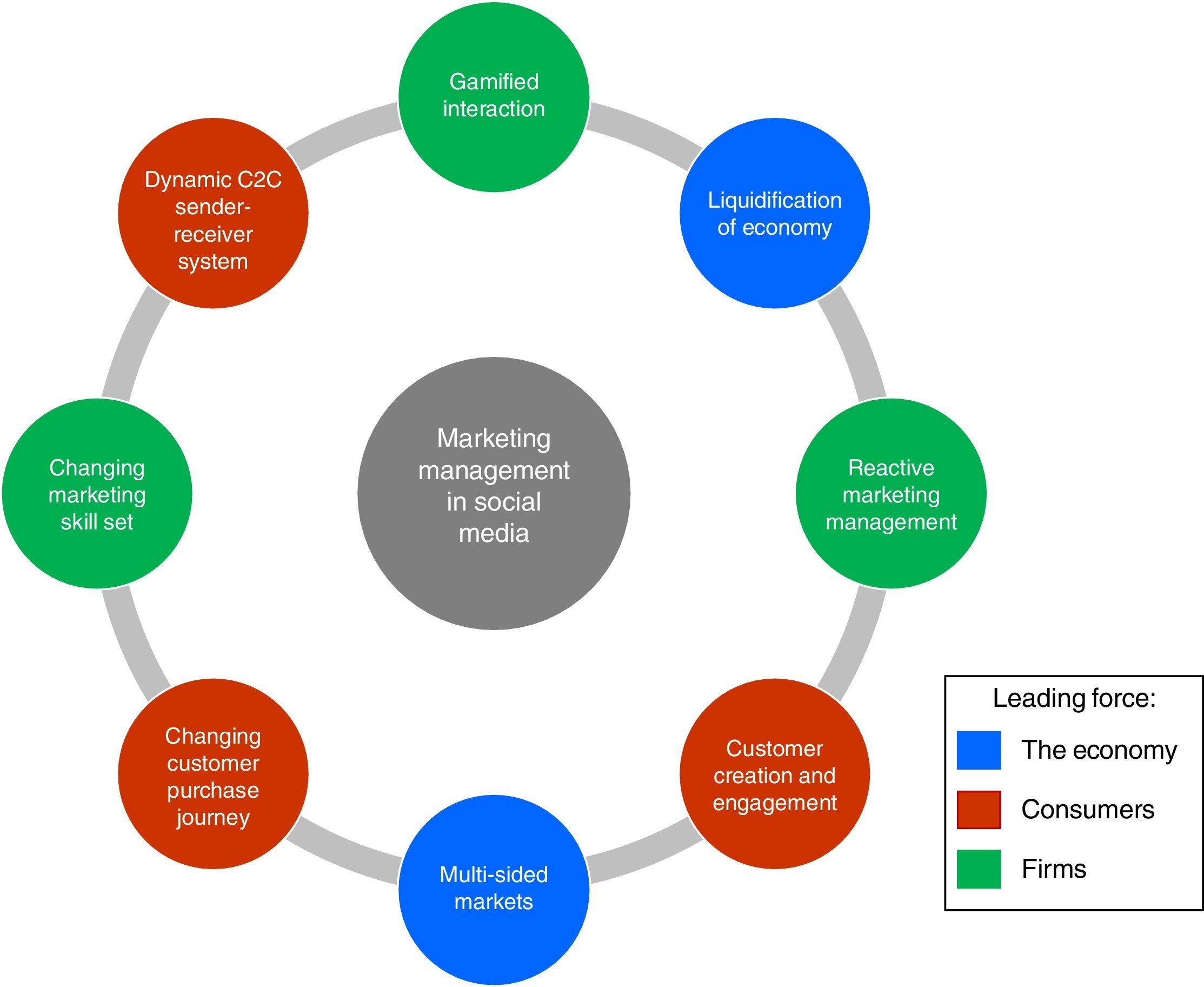

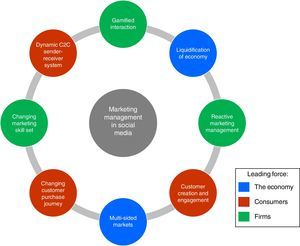

With this research we describe eight social media challenges for marketing managers and add a number of questions that academic researchers should explore in order to contribute to the development of this field. Fig. 2 presents a summary of our framework.

The challenges presented herein should be taken on in the context of increasing social media use, and specifically increasing information sharing. These trends enable and determine a wide variety of consumer behaviors and highlight a matching set of business opportunities. The well-known benefits of digital media (low cost, ubiquity, fast diffusion, etc.) have created a liquification of the economy and have brought to the fore the notion of sidedness in markets and platforms. Further, social media are particularly useful in empowering customers to freely create and engage with the brands, communities and firm actions that they most like; but also to propagate feelings and opinions among peers. This latter propagation is reshaping the purchase journey, making it more social, more shared and more public.

As digital channels throw off millions of data records, scholars and practitioners have begun to analyze big data as a relevant source of knowledge on social media use. Of course no single data source can answer all questions since experiments, surveys or qualitative studies are required to deepen our understanding into the psychological mechanisms behind consumers’ behavior in social media (Hofacker, Malthouse, et al., 2016). Researchers will need better methods and skills to integrate different types or data. Collaborative research projects with firm, and even public institutions, might well favor deeper understanding of the phenomena described in this article.

We hope this work advances the field beyond previous challenges on Internet usage an e-commerce by focusing on social media issues that are still currently emerging. Nonetheless, our research has necessarily missed many other questions dealing with social media marketing management. For instance, privacy and security concerns continue as a primary threat to social media use by both firms and customers. Exacerbating the problem, it is difficult to quantify the number of users who quit social media. Epidemiological models of social media (Cannarella & Spechler, 2014) and millennials’ preference for new and more customized instant social media (Bolton et al., 2013) suggest that marketing managers should move forward aggressively to protect users’ privacy and security. It is also the case that both scholars and practitioners need to be attentive to new businesses based on the combinations of the above challenges. As an example, consider Pokemon Go, a business model that combines geolocation, gamified interaction, C2C systems, and multi-side markets.

Managers must also cope with the specific challenges of social media in their own industry. Along those lines, some authors have already outlined recommendations for social media management in very different sectors such as tourism (Xiang & Gretzel, 2010), public management (Bertot, Jaeger, & Hansen, 2012) or advertising (Okazaki & Taylor, 2013).

Finally, we believe that social media are in their early stages of development and that their unpredic evolution will bring on new and even more complex issues for marketers. Scholars and practitioners should seek to solve the challenged posed above if, for no other reason, to be better prepared to deal with new challenges that are no doubt coming.

Conflict of interestNone declared.