In the present study, we examined an exploratory model to assess the relationship between transformational leadership and group potency and analyze the mediating role of group identification and cohesion. The research was conducted with squads of the Spanish Army. The sample was composed of 243 members of 51 squads of operational units. Our findings highlighted the importance of the transformational leadership style of command of non-commissioned officers (NCOs) due to its positive relationship with the group potency of the squad. We also analyzed the indirect relationships between transformational leadership and group identification and group cohesion and found that the latter variables played a mediating role between transformational leadership and group potency. The conclusions of this study are relevant due to the growing importance of transformational leadership and actions implemented at lower levels of the command chain for the success of missions of security organizations and defense.

En el presente estudio se examina un modelo exploratorio que evalúa la relación entre liderazgo transformacional y potencia del grupo donde se analiza el papel mediador de la identificación de grupo y la cohesión grupal. La investigación se realizó con pelotones del ejército español. La muestra se compuso de 243 miembros de 51 pelotones de unidades operativas. Se destacan de los resultados la importancia del estilo de liderazgo transformacional en el mando de los suboficiales debido a su relación positiva con la potencia de grupo. Se analizaron las relaciones indirectas entre variables existiendo un papel mediador de la identificación y la cohesión entre liderazgo transformacional y la potencia del grupo. Las conclusiones de este estudio son relevantes debido a la importancia del liderazgo transformacional para ser ejercido en los niveles más básicos de la cadena de mando con objeto de obtener éxito en las misiones asignadas a las organizaciones de defensa y seguridad.

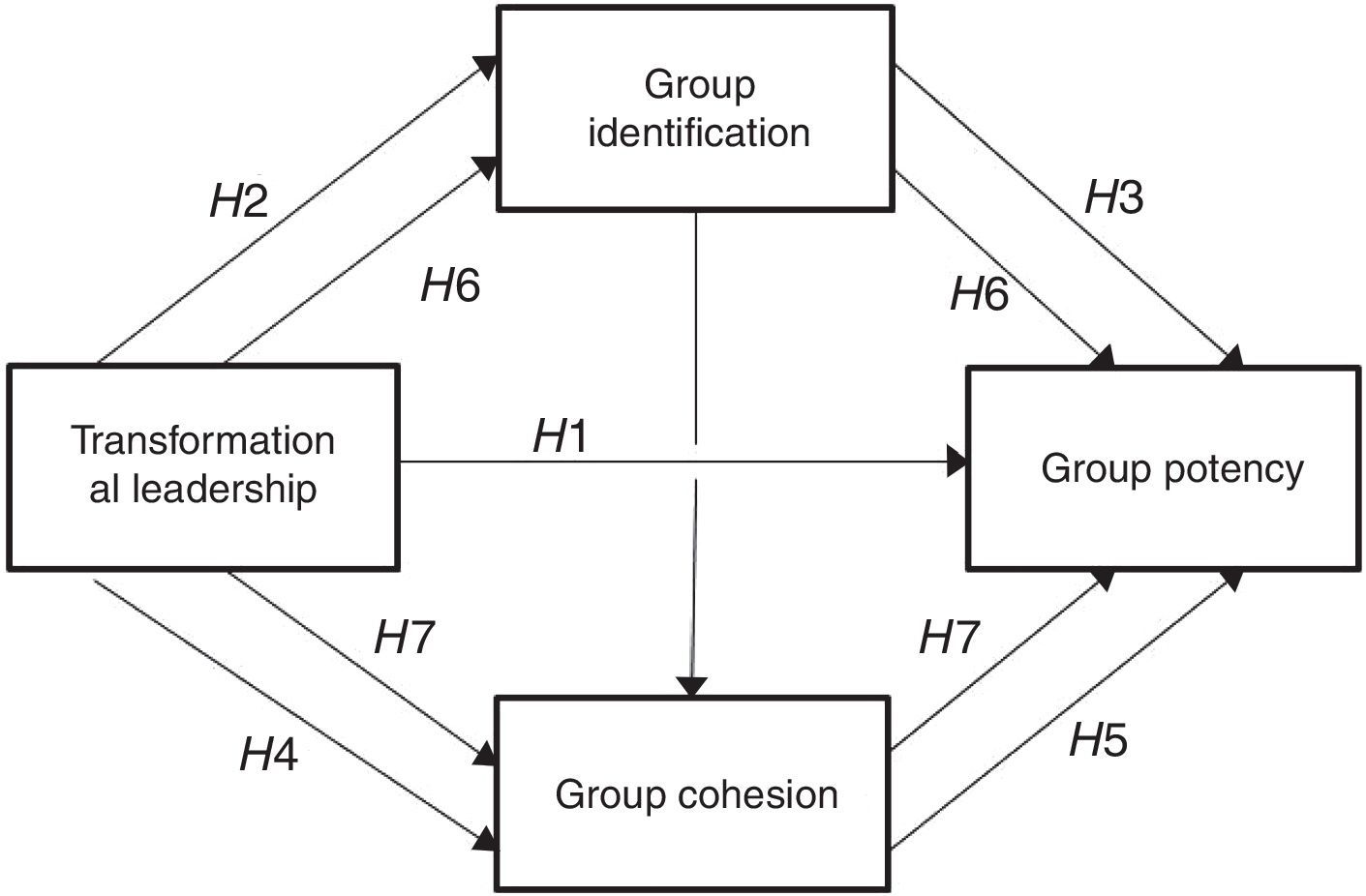

In the present study, we explored the influence of transformational leadership on group potency, a variable that is closely related to group performance. We identified two ways through which leadership may have an impact on group outcomes: group identification and group cohesion.

Our research focused on small military units in the Spanish Army. The profile of small units in military operations has progressively increased over the last few years. In armies, small units often operate in remote scenarios and under extreme conditions with no direct supervision from commanding officers. Thus, factors such as leadership, cohesion, and potency in the most basic units of military organization are becoming increasingly important for military decision makers.

Bass, Avolio, Jung, and Berson (2003) proposed a model of transformational leadership (TL) in which they analyzed the influence of TL on group cohesion, group potency, and unit performance of military units. Their model inspired many studies in the past decade. In the military field, research about these aspects is especially scarce at the squad level, even though these units are of great importance, both considering the level of responsibility and the roles assigned to them to achieve success in military operations.

Group potency is a key component of group effectiveness. Several studies have pointed to confirm the existence of a positive relationship between group potency and group performance (Gully, Incalterra, Joshi, & Beaubien, 2002; Shea & Guzzo, 1987).

In the military environment, where it is often difficult to measure effectiveness, group potency can be a very useful indicator of the degree of preparation of units to tackle their missions. In previous studies, group potency has significantly predicted efficacy and was also positively correlated with mental task performance, physical task performance, and commander ratings of team performance (Jordan, Field, & Armenakis, 2002).

Authors such as Shamir, Zakay, Brainin, and Popper (2000) and more recently Haslam, Reicher, and Platow (2011) have underlined the importance of group identification processes in achieving group's objectives. Such identification is materialized as a process of reciprocal influence between leaders and followers.

Throughout history, cohesion is another factor that has been considered critical for groups to be able to fulfill their missions (Griffith, 1988; Jung & Sosik, 2002; Tziner & Vardi, 1982). Recent studies (Shamir et al., 2000; Siebold, 2007, 2012) have highlighted that cohesion is a determining factor of the effectiveness of military units (Tziner & Chernyak-Hai, 2012), since these units often face high-risk situations (Hannah, Uhl-Bien, Avolio, & Cavarretta, 2009).

Zaccaro and Klimoski (2002) raised the importance of developing models that explain the collective effectiveness of teams including the variables that contribute to collective action and leadership processes. We consider that it is especially interesting to jointly explore collective effectiveness, leadership, and relevant variables for teams, such as group cohesion and group identification in military organizations where leaders are formally established.

The objective of the present research was to analyze the direct and indirect effects of the transformational leadership of squad leaders (i.e., non-commissioned officers) on group potency. Group Identification and group cohesion were considered as mediating or indirect variables. The relationship between the various group variables that we included in our research is explained below.

Transformational leadershipTransformational leadership (TL) is one of the theories that have generated the largest volume of research in the area of Psychology, and such productivity has been reflected in numerous spheres of organizational and social psychology (Bass & Bass, 2008). Transformational leaders are those who achieve a change in their followers through their charisma and vision and are able to develop a personal motivation among their followers. Transformational leadership is composed of inspirational motivation, idealized influence, individualized consideration, and intellectual stimulation. Avolio and Bass (2004) and Jung and Sosik (2002) have proven that transformational leadership is closely related to criteria such as cohesion, organizational effectiveness, satisfaction of employees with their supervisor, and perceived group performance. This theory has also been studied in the military context (Bass et al., 2003) and has become a reference and inspiration for military doctrine in various countries, suggesting that the leadership style of officers is of key importance and further research is needed on TL to better understand its impact on organizations.

Group PotencyIn the present study, group potency was understood as “the collective belief in a group that it can be effective” (Guzzo, Yost, Campbell, & Shea, 1993, p. 87). This construct is considered essential to take action successfully when the group faces a difficult environment (Shamir et al., 2000) and helps to understand group processes and their relationship with group performance (Alcover & Gil, 2000; Bass et al., 2003).

Group potency and collective efficacy will be treated in this manuscript as different constructs in line with previous research groups’ theoretical approaches (Gully et al., 2002a,b; Jung & Sosik, 2002; Stajkovic, Lee, & Nyberg, 2009). Despite their similarities, Gibson (1996) suggested that these constructs are distinguishable on the basis of sharedness and task specificity (Gully et al., 2002a,b). Group potency is a shared belief (Guzzo et al., 1993) and is primarily a group-level construct. The concept of group potency was proposed by Shea and Guzzo (1987) to be a key determinant of team effectiveness (Gully et al., 2002a,b).

Previous studies have examined the complex relationship between group potency and team effectiveness (Ilgen, Hollenbeck, Johnson, & Jundt, 2005). Jung and Sosik (2002) suggested a positive relationship between group potency and group performance (Stajkovic et al., 2009). Thus, research has shown that performance is better in teams that score high rather than low in potency, and a significant positive association between potency, on the one hand, and productivity, employee satisfaction, and managerial ratings of performance, on the other hand (Campion, Papper, & Medsker, 1996; Duffy & Shaw, 2000; Stajkovic et al., 2009).

Bass et al. (2003) explored leadership in platoons, which are larger than squads, and found positive relationships between transformational leadership and unit cohesion and potency. Sivasubramaniam, Murry, Avolio, and Jung (2002) examined how leadership within a team could predict levels of group potency and group performance over time.

Sosik, Avolio, and Kahai (1997) and Jung and Sosik (2002) explored transformational leadership style and concluded that group potency is a mediating factor between leadership and group effectiveness. Based on such studies, we developed the following hypothesis without considering the possible effects of indirect relationships between other variables:H1 The transformational leadership style of squad leaders will be directly and positively related to group potency in squads.

Organizational identification is understood as “the perception of oneness with or belongingness to an organization” (Ashforth & Mael, 1989, p. 34). It is considered to be a specific type of social identity according to which members assume that they belong to an organization. In this study, the organization studied was the squad, a group or unit of small size, and organizational identification with the squad was defined as group identification. Military organizations, depending on their size and structure, are not single and indivisible entities but rather networks of groups that may elicit feelings of identification with smaller units such as squads, which are closer to the everyday life of members.

As regards the antecedents of group identification, in studies with military units, Shamir et al. (2000) observed that it is influenced by certain behaviors of leaders, such as highlighting shared values or inclusive behaviors. These authors found a positive relationship between social identification and some aspects of potency understood as a component of unit effectiveness. In addition, the social identity theory of leadership (Hogg, Van Knippenberg, & Rast, 2012) explains leader-follower relations as a group process generated by social categorization and prototype-based depersonalization processes associated with social identity. According to Shamir et al. (2000), social identification is an important basis for collectivistic work motivation. Based on the theoretical postulates of Haslam et al. (2011) and Reicher, Haslam, and Hopkins (2005), according to which leadership plays a major influence on organizational identification, we proposed the following hypothesis:H2 The transformational leadership style of squad leaders will be directly and positively related to group identification in squads.

As regards the consequences of group identification, in an analysis of military units, Shamir et al. (2000) highlighted the importance of social identification as a collective source of motivation at work. They also highlighted the relationship between the social identification of military personnel in companies and group potency. The theoretical origin of such relationships is the Social Identity Theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1985), which suggests that identity is based on self-categorization and group membership processes. Hogg, Abrams, Otten, and Hinkle (2004) provided theoretical foundations that highlighted the importance of the perspective of social identity in promoting membership in the group and eliciting group processes that favor the development of collective self-conception in groups.

The theoretical postulates of Haslam et al. (2011) also underlined the importance of organizational identification, which enables group processes based on reflecting, representing, and realizing reality and makes it possible to reach the objectives set. Based on such theories we developed the following hypothesis:H3 Group identification will be directly and positively related to group potency in squads.

One of the definitions of group cohesion most frequently used in the literature is “a dynamic process that is reflected in the tendency for a group to stick together and remain united in the pursuit of its instrumental objectives and/or for the satisfaction of member affective needs” (Carron, Brawley, & Widmeyer, 1998, p. 213). Regarding cohesion in military units, Siebold (2012) highlighted the existence of a social group that remains united despite external threats and is able to achieve material and psychological objectives thanks to the psychosocial reinforcement among its members.

The importance of cohesion in military units was a clear finding of the meta-analytical review conducted by Oliver, Harman, Hoover, Hayes, and Pandhi (1999). The review revealed the importance of cohesion and its positive relationship with group and individual performance, job satisfaction, retention, well-being, and readiness. In the present study, we followed the approach of Ahronson and Cameron (2007), who studied cohesion in the Canadian Army using the model developed by Carron, Widmeyer, and Brawley (1985).

Several studies have analyzed the relationship between cohesion in military units and leadership (Arthur & Hardy, 2014; Bass et al., 2003). Tziner and Chernyak-Hai (2012) argued that high-cohesiveness crews perform best under the leadership of a commander who exercises high involvement both in the process of task accomplishment and in the interpersonal arena.

Bartone, Johnsen, Eid, Brun, and Laberg (2002) found that the influence of leadership on group cohesion can be increased by familiarity and the fact of performing challenging tasks in small military units. In accordance with the characteristics of transformational leadership style behavior, in which leaders combine an individual relationship with followers with a shared vision of the future at the squad level, we developed the following hypothesis:H4 The transformational leadership style of squad leaders will be directly and positively related to group cohesion in squads.

Several studies have shown a relationship between group cohesion and effectiveness (Beal, Cohen, Burke, & McLendon, 2003). Cohesion can be considered as an important characteristic of groups, as it allows them to assume that they will be able to overcome the difficulties of their environment. Cohesion enables groups to have the commitment of their members, to coordinate actions, and to persevere in the performance of tasks. In the Spanish Army, the psychological potential of units is often measured with an instrument known as Cuestionario para la Estimación del Potencial Psicológico de Unidad (CEPPU-03; Questionnaire to estimate the psychological potential of units). According to this questionnaire, cohesion is one of the factors that determine the psychological potential of the unit. This instrument is used to study both companies and battalions (García, Gutierrez, & Núñez, 2005). However, a review of specialized literature shows that little research has been conducted on the effects of group cohesion on group potency in small military units, particularly in Spain, where it takes two years of specific training in a military academy to become a squad leader. Zaccaro, Rittman, and Marks (2001) developed a model that can also be analyzed considering the self-perception of followers. In this model, the stages prior to the effectiveness of the teams are based on actual processes of coordination and motivation linked to cohesion. Based on the above-mentioned points, we developed the following hypothesis:H5 Group cohesion will be directly and positively related to group potency in squads.

In the present research, we proposed that TL develops processes of influence that contribute to a greater identification of members with the group (Haslam et al., 2011; Reicher et al., 2005). In the research conducted by Walumbwa, Avolio, and Zhu (2008), the authors explored the effect of transformational leadership on rated performance in individuals and found that it was also mediated by the interaction of identification and means efficacy. Shamir, Zakay, Breinin, and Popper (1998) highlighted leader behaviors that raise the salience of certain values and identities in followers’ self-concepts and constitute a framework for a group's mission and the roles of followers based on such values and identities. Based on their research and the theoretical approach of Haslam et al. (2011) and Reicher et al. (2005), according to which leadership plays a predominant role related to organizational identification in the development of group processes, we developed the following hypothesis:H6 The transformational leadership style of squad leaders will be indirectly related to group potency through group identification in squads.

The relationship between transformational leadership and cohesion has been explored in various studies, which have highlighted the influence of cohesion on collective-efficacy team performance and unit performance (Bass & Bass, 2008). In the military context, Tziner and Vardi (1982) also conducted a study on tank crews in the Israeli army that revealed a significant effect of leadership style on performance, mediated by cohesion.

Sivasubramaniam et al. (2002) argue that the behavior of transformational leaders influences group potency. According to them, military unit leaders must articulate a vision oriented toward the missions and tasks assigned to the squad; these missions and tasks must be achieved by means of team cohesion and the distribution of responsibilities.

However, there are practically no studies in military literature on the effect of group cohesion as a mediator between the transformational leadership of squad leader and group potency in squads. Thus, it would be interesting to further explore the intermediate processes that characterize military units. For this reason, we proposed the following hypothesis:H7 The transformational leadership style of squad leader will be indirectly related to group potency through group cohesion in squads.

Our hypotheses are summarized in the exploratory model shown in Figure 1, in which TL is considered as an antecedent of group potency. The model postulates the existence of direct and indirect relationships between TL and group potency through both group identification and group cohesion.

We considered group size and time spent working with the evaluated leader in the team as control variables (Becker, 2005). Prior studies have found that these variables could have significant group effects. The teamwork literature has suggested that the size of the team has an inverse relationship with team performance (Easley, Devarj, & Crant, 2003) and time spent following the orders of the leader (Wheelan, 2005). Both variables could increase barriers among group members (Liden, Wayne, Jaworski, & Bennett, 2004).

MethodSample and ProcedureThe questionnaires were completed under the supervision of a single researcher by 243 members of 51 squads that belonged to four companies of infantry and two companies of sappers of a light and a mechanized brigade in Cordoba and Almeria provinces, in Spain. Such units belonged to the Ground Force that regularly participates in missions abroad. Data collection took place in September and October 2013. The participating squads had a mean size of 6 members and ranged from 5 to 12 members. Not all squad members were present when the questionnaire was administered. On average, 6 members completed the questionnaire per squad, ranging from 3 to 8. Most respondents were male (98% males and 2% females). Mean time under the orders of the leader was 16.2 months (SD=13.8); the shortest time was one month. Mean age of participants was 26.1 years (SD=5.1).

Squad leaders were in most cases with the rank of sergeant (91%) and cabo primero – a military rank between corporal and sergeant – (9%). Most squad leaders were male (96% males and 4% females). The questionnaire was administered in person in the different units and all groups received the same instructions. Questionnaires were administered only to subordinates, and each member of the squad was evaluated with regard to his/her direct supervisor. Participants were informed that participation was voluntary and that the study was confidential and anonymous.

Participation in the study was voluntary, and the researchers explained before data collection the maintenance of confidentiality and anonymity principles. The researchers explained how the collected information would be used, ensuring the participants that they could abandon their participation in the study at any time without any consequence. The questionnaire omitted personal identification data in order to assure anonymity, and the researchers committed themselves to protecting the confidentiality of the data and not to misusing respondents’ answers.

The time needed to complete the questionnaire ranged from 20 to 35minutes.

InstrumentsTransformational leadership. TL was measured using the Spanish adaptation of the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) developed by Molero, Recio, and Cuadrado (2010). This adaptation is based on the MLQ-5X, a short form developed by Bass and Avolio (1997). The scale consists of 32 items and has a composite reliability of .95. It has a 5-point Likert response scale (0=never, 4=always). Participants are asked to indicate how frequently each statement fits the style of the squad leader. Higher scores indicate a greater use of transformational leadership.

In our study, as in most studies conducted with the MLQ, we considered overall scores in transformational leadership. Due to the good reliability of the MLQ and the high correlations among the different factors (average of .81, range between .89 and .70) and the fact that Cronbach's α ranged between .86 and .64, we considered it more parsimonious to use the aggregate score. Examples of the items of the questionnaire are “Talks optimistically about the future” or “Spends time teaching and coaching”.

Group potency. We measured this variable using the scale developed by Shamir et al. (2000), translated and adapted for this study using a back translation method with bilingual staff. We followed the guidelines of Muñiz, Elosua, and Hambleton (2013) for test translation and adaptation. The questionnaire includes 4 items and reached a reliability of α=.93. Items are responded on a 5-point Likert scale (0=totally disagree, 4=totally agree). Higher scores indicate greater group potency. An example of the items of the questionnaire is “To what extent is your company prepared for routine security missions?”

Group identification. We used a scale prepared by Shamir et al. (2000) for use in military units. For the present study, the scale was translated into Spanish by the authors of this study using a back translation method with bilingual staff, following the guidelines of Muñiz et al. (2013). Although the scale has five items, we reduced it to four to improve factor loadings and reliability reached an alpha value of .88. The scale had a 5-point Likert response scale (0=totally disagree, 4=totally agree). Higher scores indicate greater group identification. An example of the items of the questionnaire is “My platoon is like a family to me”.

Group cohesion. In our study, we used the Group Integration Task subscale of the Group Environment Questionnaire (GEQ) developed by Carron et al. (1985) as a measure of cohesion because our research focused on determining aspects of squad cohesion such as the degree of unity among its components to achieve goals, cooperation, and the establishment of responsibilities among the members of the group. The Spanish version of this scale was validated by Iturbide, Elosua, and Yanes (2010). The scale has five items and reliability reached an alpha value of .87. Items are answered on a 5-point Likert scale (0=totally disagree, 4=totally agree). Higher scores indicate greater cohesion. Example of items is “Our team is united in trying to reach its goals”.

Data AnalysisThe unit of analysis in our study was the squad. We aggregated responses of squad members in the factors studied using the within-group agreement index (rWG) proposed by James, Demaree, and Wolf (1984), considering a value of .70 as sufficient to justify aggregation. The mean of rWG values for TL, group identification, group cohesion, and group potency was .90. We eliminated four groups that did not fulfill the within-group agreement criterion from the analysis. The final rWG values for TL, group identification, group cohesion, and group potency were .91, .87, .88, and .92 respectively for 48 squads and 223 members.

Data analysis and the study of the models proposed were conducted using the Partial Least Squares (PLS) statistical technique to model the relationships between observed and latent complex variables (Vinzi, Chin, Henseler, & Wang, 2010). Calculations were made with SmartPLS software, version 2.0 (Ringle, Wende, & Will, 2005).

PLS is a flexible but rigorous modeling technique (Ringle et al., 2005; Wong, 2013) that has advantages compared to covariance techniques because it can be used to predict and explore indicators and estimated statistics with small samples without the limitations of other statistical techniques (Cepeda & Roldán, 2008; Vinzi et al., 2010).

PLS accounts for measurement error and should provide more accurate estimates of mediation effects than regression analyses. Moreover, PLS was developed to avoid the necessity of large sample sizes and normal distribution of the data (Falk & Miller, 1992). Significance was evaluated using bootstrapping of 500 samples. PLS analyses follow a two-step approach. Before hypotheses are tested (inner model), reliability and validity of the measures – that is, how well manifest indicators predict the latent variables – are tested first (outer model).

In a first stage, we calculated the reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of the factors proposed for the research model. The convergent and discriminant validity of factors was also analyzed as a previous step to the assessment of the structural model. The structural model was used to assess the weight and the magnitude of the relationships between the different variables, ensuring that endogenous variables were explained by the constructs that predicted them and determining to what extent predictor variables explained the variance of endogenous variables (Cepeda & Roldán, 2008; Falk & Miller, 1992).

After that, we analyzed the direct relationships between variables according to the hypotheses, considering the first as the independent variable and the second as the dependent variable, without considering the possible effects of indirect relationships between variables. Finally, we explored direct and indirect relationships of multiple mediation (Preacher & Hayes, 2008), that complemented the traditional method of Baron and Kenny (1986).

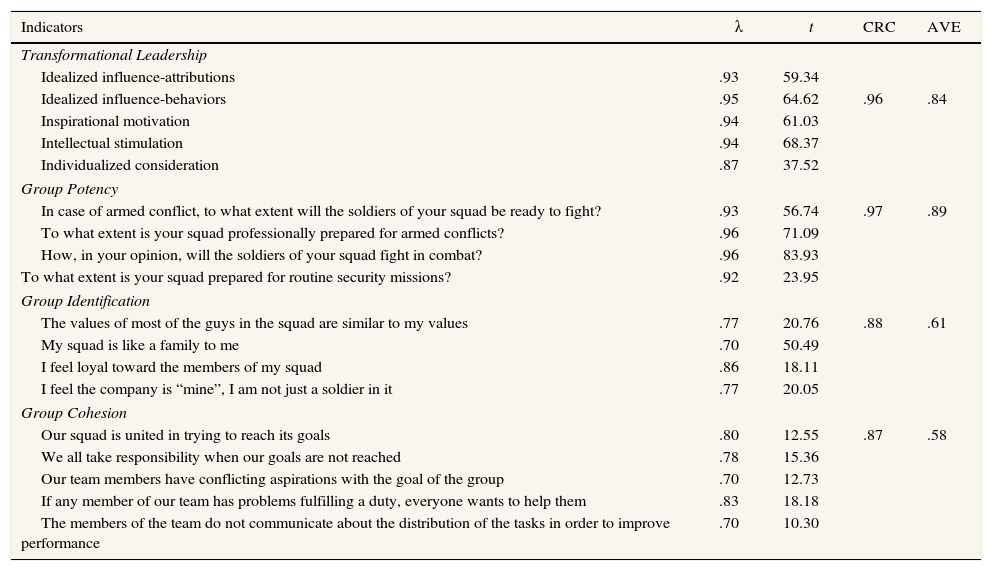

ResultsMeasurement ModelWe explored the reliability of constructs applying the criterion of Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, and Tatham (2006), that is, reaching values of loadings over .60 and a critical value of 1.96 for p<.05. Each indicator was assessed by exploring the loadings of the indicators of each construct (λ). Indicator loadings and composite reliability are shown in Table 1. Overall, the factors showed adequate discriminant validity. Specifically, they were all above .70, the reference value, which shows that the discriminant validity of the factors was adequate for the criterion used (Hair et al., 2006). This procedure yielded a composite reliability in which the different loadings of the indicators were taken into account. Composite reliability is similar to Cronbach's α but is a better indicator of reliability (Henseler, Ringle, & Sinkovics, 2009).

Individual Loadings (λ), Composite Reliability Coefficient (CRC), t-values and Average Variance Extracted (AVE).

| Indicators | λ | t | CRC | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transformational Leadership | ||||

| Idealized influence-attributions | .93 | 59.34 | ||

| Idealized influence-behaviors | .95 | 64.62 | .96 | .84 |

| Inspirational motivation | .94 | 61.03 | ||

| Intellectual stimulation | .94 | 68.37 | ||

| Individualized consideration | .87 | 37.52 | ||

| Group Potency | ||||

| In case of armed conflict, to what extent will the soldiers of your squad be ready to fight? | .93 | 56.74 | .97 | .89 |

| To what extent is your squad professionally prepared for armed conflicts? | .96 | 71.09 | ||

| How, in your opinion, will the soldiers of your squad fight in combat? | .96 | 83.93 | ||

| To what extent is your squad prepared for routine security missions? | .92 | 23.95 | ||

| Group Identification | ||||

| The values of most of the guys in the squad are similar to my values | .77 | 20.76 | .88 | .61 |

| My squad is like a family to me | .70 | 50.49 | ||

| I feel loyal toward the members of my squad | .86 | 18.11 | ||

| I feel the company is “mine”, I am not just a soldier in it | .77 | 20.05 | ||

| Group Cohesion | ||||

| Our squad is united in trying to reach its goals | .80 | 12.55 | .87 | .58 |

| We all take responsibility when our goals are not reached | .78 | 15.36 | ||

| Our team members have conflicting aspirations with the goal of the group | .70 | 12.73 | ||

| If any member of our team has problems fulfilling a duty, everyone wants to help them | .83 | 18.18 | ||

| The members of the team do not communicate about the distribution of the tasks in order to improve performance | .70 | 10.30 | ||

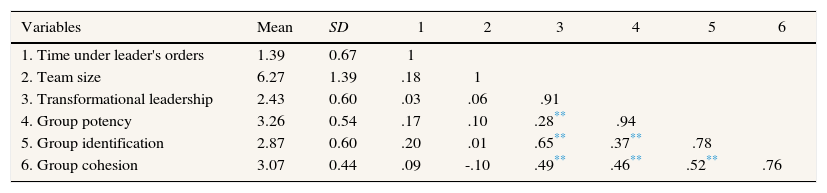

To measure convergent validity, Fornell and Larcker (1981) proposed using Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and recommended that the AVE should exceed .50. Table 2 shows the construct's factors, including means, standard deviations, correlations, and the square root of the AVE in the diagonal. One of the discriminant validity criteria was that the correlation between constructs should be lower than the indicator defined by the square root of the AVE to ensure that different phenomena are being measured (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The data suggested adequate discriminant validity. It is worth noting that significant relationships were found between all the factors and particularly between group identification and group cohesion.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations between the Variables Studied (N=243 subjects and 51 squads).

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Time under leader's orders | 1.39 | 0.67 | 1 | |||||

| 2. Team size | 6.27 | 1.39 | .18 | 1 | ||||

| 3. Transformational leadership | 2.43 | 0.60 | .03 | .06 | .91 | |||

| 4. Group potency | 3.26 | 0.54 | .17 | .10 | .28** | .94 | ||

| 5. Group identification | 2.87 | 0.60 | .20 | .01 | .65** | .37** | .78 | |

| 6. Group cohesion | 3.07 | 0.44 | .09 | -.10 | .49** | .46** | .52** | .76 |

Note. Elements in the diagonal are the square root of the AVE between constructs and their indicators.

Time spent under the orders of the leader in years. Team size in number of members. The remaining variables are reported on a 5-point Likert scale (0-4).

This was done by conducting a linear regression in which the loadings could be interpreted as standardized beta coefficients. To determine the statistical significance of the overall results and calculate Student's t for each structural effect, confidence intervals were based on a bootstrapping procedure with 500 samples (Henseler & Chin, 2010).

To analyze the predictive value of the model for the dependent latent variables, we considered the criterion of Falk and Miller (1992), according to whom the value of the proportion of variance explained (R2) should be greater than .10.

First, we analyzed the direct relationships between variables (Figure 1) according to the established hypotheses, without considering the possible effects of indirect relationships between variables. Our analysis showed the following results: we found a positive and direct relationship between TL and Group Potency (β=.37, p<.01) that explained a proportion of variance (R2) of .18. This point to confirm Hypothesis 1. An analysis of the relationship between TL and Group Identification without considering the direct relationship between TL and Group Potency showed a direct and positive relationship (β=.64, p<.01) that explained a proportion of variance of .47. This support Hypothesis 2. We found a significant positive and direct relationship between Group Identification and Group Potency (β=.56, p<.01) that explained a proportion of variance of .34, which points to confirm Hypothesis 3.

The analysis of the relationship between TL and Group Cohesion based on the value of the path without considering the direct relationship between TL and Group Potency showed a positive and direct relationship (β=.51, p<.01) that explained a proportion of variance of .29, which supports Hypothesis 4.

We found a positive and direct relationship between Group Cohesion and Group Potency (β=.56, p<.01) that explained a proportion of variance of .35, which points to confirm Hypothesis 5.

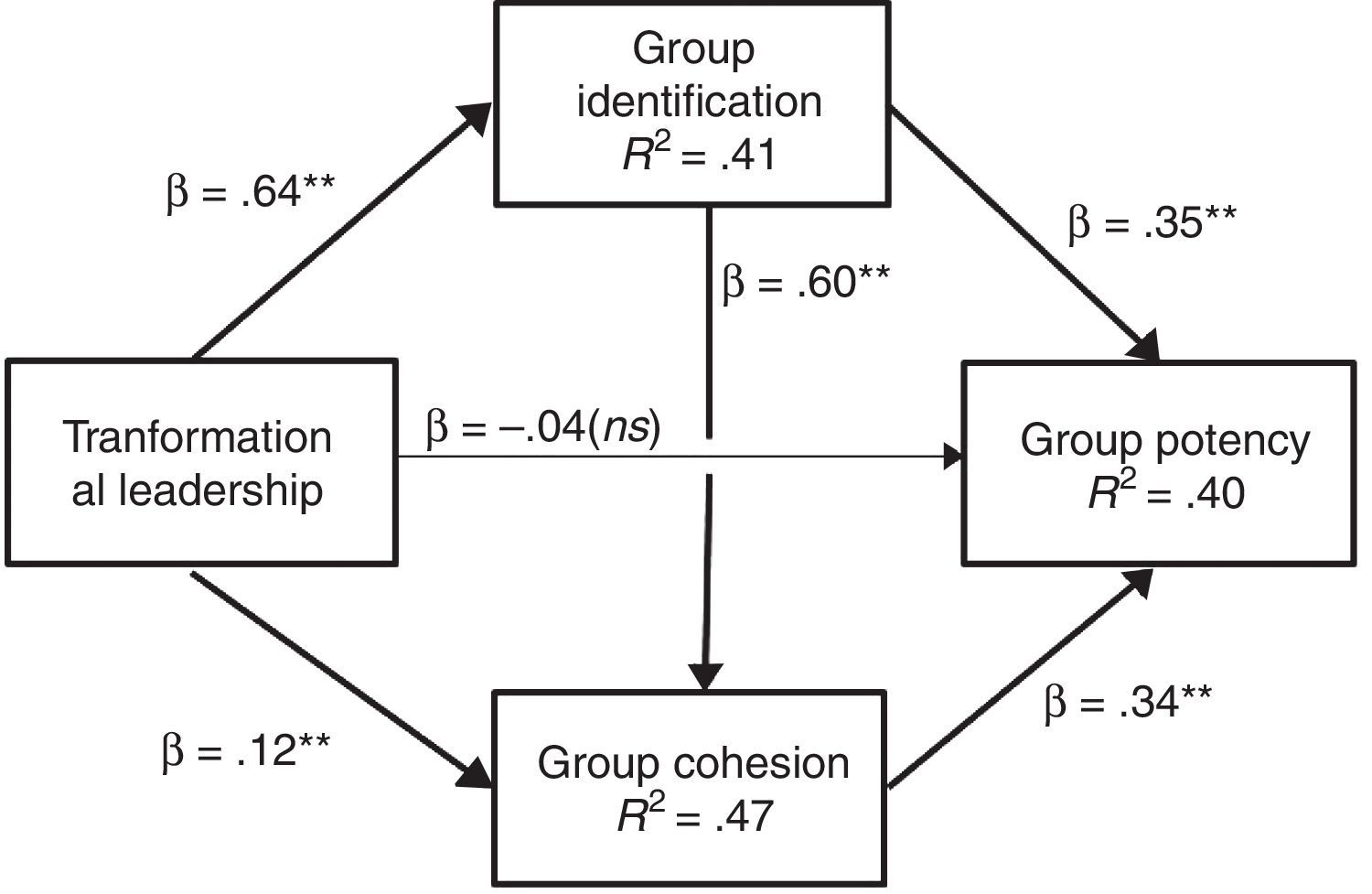

Exploring direct and indirect of multiple mediation we considered the hypotheses based on the postulates of Preacher and Hayes (2008), proposing the existence of two mediators (Figure 1). Results are shown in Figure 2.

When we explored the direct relationship between TL and Group Potency considering the overall model, we observed a considerable change in the relationship from β=.37 (p<.01) to β=- .07 (ns), with an increase in the variance explained from R2=.18 to R2=.40. The model suggests the existence of an indirect relationship between TL and Group Potency that is mediated by Group Identification and Group Cohesion, as we found significant values in the paths and the variance explained by such variables. Such results support hypotheses 6 and 7.

Team size and time spent following the orders of the leader variables were analyzed in the model; however, neither of these two variables presented a significant relation to the other variables of study.

DiscussionThe conclusions of the present study suggest that transformational leadership is important and positively related to group potency but influenced by group identification and cohesion. Although this relationship can be applied in general to small groups within organizations (Bass et al., 2003; Walumbwa et al., 2008), it should be particularly considered at squad level. Various studies have suggested the existence of a positive relationship between group potency and performance in teams (Bass et al., 2003; Sivasubramaniam et al., 2002). This relationship is interesting as it is difficult to measure the performance of military units in real-life situations, given the context of uncertainty and complexity in which military operations usually take place and the difficulty to assess the results obtained. Results highlight the importance of considering the actual transformational component at the most basic levels of military units and its possible influence on the processes of selection, training, and promotion.

Mediational factors that intervene and transmit the influence of inputs to outcomes could be explained by the input-mediator-output-input (IMOI) model (Ilgen et al., 2005; Rico, Alcover, & Tabernero, 2010). The IMOI model reflects the fact that there is a broad range of factors that could mediate the effects of team inputs on outcomes, and invokes a cyclical causal feedback. In this case, group potency serves as inputs to future team processes.

Group potency refers to a group-level phenomenon that is parallel to the individual-level construct called self-efficacy and increases the ability to accomplish goals (Jung & Sosik, 2002). This study has broadened our understanding of the mediator role of group cohesion and group identification for group potency in the group development process.

The present study also highlighted the existence of an indirect relationship between TL and group potency through group identification. In squads, group identification promotes organization and coordination between members and facilitates their protection in situations of stress, anxiety, or fear associated with contexts of risk such as those caused by explosive threats, armed attacks, and uncertain operations. Military missions on the ground often involve situations of isolation, with a lack of direct instructions from higher levels and a very fast evolution of events. All this highlights how important it is for soldiers to identify with their groups, including those in the barracks and also those set up in areas of operations.

The study also highlights the importance of group cohesion in the relationship between TL and group potency.

Zaccaro and Klimoski (2002) highlighted the importance of leadership in developing the collective efficacy of units under stress. Our findings suggest that this perception of collective efficacy (similar to group potency) can be obtained through the cohesion between team members and the development of a group identity. Regarding cohesion, both leader-follower and follower-follower relations have been analyzed by various authors specialized in military cohesion (Salo and Sinko, 2012). Results of studies confirm the importance of promoting opportunities to increase cohesion at squad level as parts of larger units.

In the present study, we explored factors of group cohesion related to the distribution of responsibilities between the members of the group, effective communication, review of job procedures, and definition of common objectives. Our results suggest that transformational leaders of squads who promote group integration with the task will increase group potency. One of the possible explanations to this is that members who identify with the group will tend to “own” their tasks and feel united to perform them. This approach is complemented by the conceptualization of Zaccaro et al. (2001), according to which leaders perform a number of tasks related to information and management that ultimately facilitate the transfer of their vision of the mission to the members of the team in order to perform a collective action.

Our research also raises the importance of transformational leaders at the squad level and their tasks related to the promotion of group identification through shared values as well as the development of relationships based on mutual loyalty and affection between members of the group. In the model presented here, leadership can be understood as an individual variable that exerts its influence on a group variable – group potency – through identification of individuals with the group and increases group cohesion around a joint task.

The present study has certain limitations. First of all, the measures were obtained through self-reports, which may have increased the bias of the common variance by using a single measuring system (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). It would have been interesting to include various indicators of the factors studied from different sources. Another possible limitation is that we studied the factors in groups, aggregating data, and conducted a limited multilevel analysis (Yammarino & Dansereau, 2011). Multilevel theoretical models can improve our understanding of organizational phenomena. Such limitations could be overcome in future studies by broadening the levels of analysis and trying to analyze psychosocial phenomena with multiple causes.

The cross-sectional model of this study could be one limitation, and future research should examine the IMOI model suggested (Ilgen et al., 2005; Rico et al., 2010) in longitudinal studies to analyze the role of leadership in group cohesion and identification to increase group potency.

Another limitation could be the minimum sample size required (Wong, 2013). Even though PLS is well known for its capability of handling small sample sizes, 48 groups could still be a small sample.

The present study highlights the importance of factors based on behaviors of military leaders and on characteristics of units at tactic levels that are the basis of operational and strategic levels. Our study suggests the need to promote selection, training, and promotion at the squad level, enhancing group identification and cohesion between members, which are the cornerstone of small units, particularly during operations. As leaders of small units that belong to sections and companies, squad leader require proper training and skills to promote a transformational leadership style. The importance of achieving group potency in military units lies in the collective motivation that this construct represents. Group potency is one of the pillars of the human factors that, together with material factors, enable the military capabilities that armies require to fulfill their missions.

One of the possible future lines of research proposed is to consider the various factors involved in transformational leadership and the potential influence of different mediator variables. Although some progress has been made in recent years in the differentiation between transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership, further research is needed on the charismatic-transformational paradigm. Another potential area of interest for new studies is to attempt to better operationalize social identification and organizational identification constructs (Haslam et al., 2011).

To conclude, the theoretical model proposed suggests that military leaders at the most basic levels with a transformational leadership style promote group potency by developing group identification and cohesion in the squad. In the armed forces, squads are key to undertake missions in the complex and uncertain environments that are so characteristic today. In military units, group potency is considered as a key human factor to reach the preparation required and be able to conduct the missions entrusted by society to its armed forces.

Conflict of InterestThe authors of this article declare no conflict of interest.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Spanish Army Training and Doctrine Command (MADOC) for encouraging this research, assisting in carrying it out, and the time devoted by the soldiers to the collection of data. They are also indebted to the reviewers for their detailed and positive comments.