Hepatic osteodystrophy is any bone disease in patients with chronic liver disease. To measure bone mineral density (BMD) T-score by bone densitometry (BD) is used, classifying the disease in osteopenia, osteoporosis and severe osteoporosis. There are not criteria for monitoring and detection of osteodystrophy in cases of non-cholestasic cirrhosis. To determine the risk of fracture at 10 years, Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX), could be useful.

ObjectivesDetermine the frequency of hepatic osteodystrophy in cirrhotic patients according to BD and FRAX and identify associated risk factors.

Patients and methodsAn observational, analytic, cross-sectional study. We included cirrhotic patients with report of DO and FRAX.

Results52 patients were included, 38 were female (73.1%). The mean age was 12.29±55.46 year-old, MELD 4.14±11.71. In cholestatic etiology Mayo Score was 2.9±3.31. The BMD was 0.756±0.1896mg/ cm 2 and T-score -2.34±1.0. Of all patients, 26 (50%) had ranges of osteopenia and 21 (40.4%) of osteoporosis. Fracture risk with FRAX 10-year was 7.77±6,713, and when we added the value of T-score fracture risk was 13.72±12. Higher prevalence of cholestatic diseases in women and viral etiology in men (P=0.006) was observed. There was significant relationship between cholestatic etiology T-score, alkaline phosphatase, and elderly and FRAXS with T-score (P=<0.05). Vitamin D was lower in patients with cholestatic liver disease (P=0.047) and a trend towards lower value of FRAX in patients with cholestatic liver disease was observed.

ConclusionsThe frequency of osteoporosis or osteopenia is 90.4% in Mexican patients with liver cirrhosis of different etiologies. The decreased levels of bone alkaline phosphatase and 25-hydroxyvitamin-D were correlated with the risk of bone disease in patients with liver cirrhosis.

La osteodistrofia hepática es cualquier enfermedad ósea en pacientes con enfermedad hepática crónica. Para medir la densidad mineral ósea (DMO) se utiliza la escala T-score por Densitometría ósea (DO) clasificando la enfermedad en osteopenia, osteoporosis y osteoporosis severa. No hay criterios establecidos para el seguimiento y detección de osteodistrofia en cirrosis de causa no colestásica. Para determinar el riesgo de fractura a 10 años, el Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX), podría ser útil.

ObjetivoConocer la prevalencia de osteodistrofia hepática en pacientes cirróticos de acuerdo a DO y FRAX, e identificar factores de riesgo asociados. Pacientes y Métodos: Estudio observacional, analítico y transversal. Incluimos pacientes cirróticos con reporte de DO y FRAX.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 52 pacientes, 38 (73.1%) fueron mujeres. La edad promedio fue 55.46±12.29 años, MELD 11.71±4.14, en etiología colestásica el Mayo Score fue 2.9±3.31. La DMO 0.756±0.1896mg/cm2 y T-score -2.34±1.0. Tuvimos 26 pacientes (50%) con osteopenia y 21 (40.4%) con osteoporosis. El riesgo de fractura a 10 años por FRAX fue 7.77±6.713, que aumento a 13.72±12 al considerar FRAX más T-score. Hubo mayor prevalencia de enfermedades colestásicas en mujeres y virales en hombres (P=0.006). Hubo relación entre etiología colestásica y T-score, fosfatasa alcalina, edad avanzada y FRAXS más T-score (P=<0.05). La 25-hidroxivitamina D fue menor en pacientes con hepatopatías no colestásicas (P=0.047) y se observó una tendencia a menor valor de FRAX en pacientes con colestasis.

ConclusiónLa frecuencia de osteodistrofia fue de 90.4%. Los niveles disminuidos de fosfatasa alcalina ósea y de 25-hidroxivitamina-D se relacionaron con riesgo de osteodistrofia en pacientes cirróticos.

Osseous illness in patients with advanced chronic liver disease is known as osteodistrophy (OH), mainly including osteomalacy and osteoporosis.1 It is a common complication of liver cirrhosis that can worsen after hepatic transplant (TH) due to immunosuppression, leading to a significant risk of fractures, with impact in morbidity, life quality and even survivability.2 Osteoporosis is characterized by a reduction in the level and quality in the osseous mass, associated with an increased risk of fractures due to fragility.3 Diagnosis is determined by measuring the osseous mineral density (DMO) and by detecting fractures. A value inferior to -2.5 in the T scale indicates osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and in men older than 50 years. When this value lies within -1 and -2.5, it is classified as osteopenia or reduced osseous mass.4 The probability that a 50 year old person develops a hip fracture, is 14% in women and 5-6% in men. The risk of vertebral deformity is 25% in postmenopausal women.5 Different prevalence rates in osteoporosis have been found, according to the cirrhosis aetiology: For viral hepatitis C 50%, for viral hepatitis B 10%, in alcoholic hepatopathy 30% and in self immune disease between 12-55% in different series.6 Osteomalacy is linked to cholestasis disease such as Primary Biliary Cirrhosis (CBP) and Sclerosing Cholangitis (CE). Osteoporosis in patients with hepatic conditions involves mainly the trabecular bone, characterized by a decrease in DMO, poor functioning of osteoblasts, an augmentation in osteoclastic cells activities and low levels of osteocalcine. It is known that osteoporosis is directly related with the type, severity and progression of hepatic disease.7 In cirrhotic patients there is a diminishment of 25 D hidroxi-vitamin and 1.25 D dihidroxi-vitamin, with a loss in DMO more frequently in the spine. In percentages of osteopenia and osteoporosis, according to the European Osteoporosis Foundation, the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the US, and the World Health Organization, four categories for diagnosis have been established: (T-score) normal: DMO not higher than one standard deviation (DE) lower than T-score. Low osseous mass or osteopenia: DMO higher than 1 but lower than 2.5 DE under the T-score. Osteoporosis: DMO higher than 2.5 DE. Severe or Established Osteoporosis: DMO higher than 2.5 and 1 or more vertebral compression fractures, with annual follow up in patients with risk factors and otherwise every 2 or 3 years.8 In patients with chronic cholestasis, osteoporosis has been reported in women in 37%. In India in 2009 there was a report of 68% of cirrhotic patients due to viral infection. In the patients with B hepatitis the prevalence was of 68% and 100% in patients with C hepatitis. Caused by alcohol a prevalence of 56.7% was found. There has also been research in the relation between antiretroviral therapy against hepatitis and the development of osteopenia, without any concluding evidence.9 Most of the patients with hepatic transplant had a fast loss in osseous mass during the first 6 months after the transplant, reaching 6% in lumbar spine in 3 months.10 Studies have shown low osteocalcine serum values (mark protein of the osteoblastic function) and reduction in trophic factors such as grow factor similar to insulin (IGF-1). A reduction in IGF-1 has been described in cirrhotic patients. Studies have shown that the administration of IGF-1 increase the osseous mass and the DMO in cirrhotic rats.11 In cholestasis hepatopathies it is related with the increase in bilirubin and biliary acids, as a consequence of cholestasis or of the hepatic disease in the development of osteodistrophy due to the harmful effect of not conjugated bilirubin over the osteoblastic cell viability and proliferation. However, this has been questioned by studies made in populations with Gilbert Syndrome, where no association was found. Yet, the harmful effect of bilirubin has to be evaluated within a global context of hepatic disease, with simultaneous increase in biliary acids, inflammatory cytokines and in the state of the phosphocalcic metabolism, including D vitamin and parathyroid hormone.12 Lithocholic Acid (LCA), same as D vitamin, is an antagonist of the vitamin D receptor (VDR).13 The LCA reduced the vitamin D capacity of activating genes involved in the metabolism of vitamin D. Hence, the increase in lithocolic acid, second to cholestasis, would interfere with vitamin D in its receptive level and would diminish the expression of genes related to the osseous formation. This has been related with increased intensity in patients with hepatic insufficiency accompanied by hypoalbuminemia.14

In chronic hepatic disease, the complete study with radiography of the dorsal and lumbar spine, in lateral projection, to identify previous fractures. Calcium levels (corrected with albumin), phosphor, 25-hidroxivitamin D, of parathyroid hormone, renal function. Biochemical marks of osseous interchange are used to value the response to treatment: alkaline phosphatase, serum osteocalcine, peptide serum of procollagen type 1 (formation), N-telopeptide, C-telopeptide and desoxiporidonoline (resorption). However, they can be modified by hepatic fibrosis. If osteomalacy is suspected by defect in the mineralization, a trans-iliac biopsy is indicated. Osseous densitometry (DO) in patients with advanced cirrhosis, ascites higher than 4 litres can give false positives.15 A study in patients with hepatopathic cholestasis identifies polymorphism COLIA1 as a genetic marker of osseous mass in postmenopausal female patients with CBP and osteoporosis. COLIA1 Sp1 could identify subgroups of patients with CBP before the development of osteoporosis.16 In the actuality the realisation of DO by DEXA has not been enough to identify persons with risk of fracture due to specific measurements that lack sensibility. Dr. Kanis and collaborators, carried out a meta-analysis, with the purpose of identifying the risk values independent of the DMO. From the outcomes resulted the FRAX tool (Fracture Risk Assessment Tool): a model that allows the prediction of the absolute risk of osteoporotic fracture in 10 years, integrating clinical risk factors and, if available, the results of the DMO; classifying people with greater risk and candidate to treatment. It values age, gender, corporal mass index, antecedents of personal fracture and femur fracture in progenitors, tobacco and steroids use, rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis, secondary osteoporosis causes, alcoholism and optionally the T index value of the femurs neck, measured by X-rays DO of double energy. This allows to calculate the absolute risk of proximal femur fracture or of any other mayor osteoporotic fracture in the following 10 years. In a study performed in Spain in 2009, it was concluded that the risk of fracture of FRAX is higher in patients that received previous treatment with steroids.17 However, it has never been used to evaluate patients with hepatopathy, considering it as a cause of secondary osteoporosis. This tool helps in the taking of decisions and stems from the necessity of taking out complementary accessory tests or the indication and necessity of pharmacological treatment.

This study had the purpose of researching the prevalence of hepatic osteodistrophy in a sample on cirrhotic patients of the Mexico General Hospital (MHG), according to the DMO y FRAX risk, and to identify the associated risk factors.

Patients and methodsA transversal analytic study was conducted, in which the clinical expedients of cirrhotic patients of MHG and the individual risk of FRAX fracture was calculated. This study included patients with diagnosis of cirrhosis whose are treated in the clinic of the MHG with DO. We recorded whether there was a history of hip fracture or vertebral column or any previous fracture. Individual FRAX fracture risk with validated computer tool, which ultimately yields the risk of 10-year fracture and T-score values were obtained by OD was calculated. Patients with antecedents of cirrhosis that had had an hepatic transplant, chronical renal disease and hypogonadism, thyroidal disease, cirrhosis of autoimmune nature that had received treatment with steroid, other pathologies of autoimmune origin or hepatic cirrhosis due to infection by VHC that are taking antiviral treatment, have been excluded. The statistical analysis was done in accordance to the variables and parametric and non-parametric tests were applied, for the description of variables, measures of central tendency and dispersion were made. T student test was used for quantitative variable and x2 for qualitative. 2 ways ANOVA was used for the analysis between groups, considering a value of P < 0.05 statistically significant.

Statistical analysis: The qualitative variables were expressed as proportions and percentages, numerical as mean and standard deviation. For comparison between groups, Student's t test was used for quantitative and qualitative variables X2. To evaluate correlation between variables correlation coefficient r2 of Pearson was used. A value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsDemographic and biochemical characteristicsFive hundred expedients of the Gastroenterology Service, of the Transplant Clinic, and the Liver Clinic were assessed, of which 52 patients fulfilled the criteria of inclusion to the study. The average age was 55.46±12.29 years. Of them 38 were women (73.1%) and 14 men (26.9%). All the patients fulfilled the biochemical and by ultrasound criteria of hepatic cirrhosis. The different aetiologies of cirrhosis that were found, were: alcohol in 6 patients (11.5%), viral in 6 patients (11.5%), autoimmune in 5 patients (9.6%), cholestasis disease in 25 (48.1%), non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (EHNA) in 5 (9.6%) and idiopathic in 5 patients (9.6%). The gravity of the disease was evaluated with the Child Pugh (Child) scale, 9 (17.3%) patients were Child A, 20(38.5%) were Child B and 21 (40.4%) were Child C. The MELD mean was 11.71±4.14 and for the cholestasis origin causes the Mayo Score was calculated, which was 2.9±3.31. The data of portal hypertension by endoscopy with oesophageal varices and ultrasound findings, corresponded to 32 patients (61.5%). According to the nutritional state of the population, the body mass index (BMI) was classified in different nutritional ranges, 1 patient (1,9%) with underweight, 25 (48.1%) patients within the normal parameters, 21 (40.4%) with overweight, 4 (7.7%) with grade I obesity, 1 (1,9%) with grade II obesity and no patient in grade III. The serum studies of importance were: Albumin 2.971±0.7261g/dl, total bilirubin 2.47±0.21mg/dl, aspartate aminotransferase 66.27±46.83 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 60.27±46.81 U/L, gamma-glutamiltransferase 190.31±0.75 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 228.29±186.47 U/L, lactic dehydrogenase 173.85±3.15 U/L.

Osseous evaluationThe average of DMO was 0.756±0.1896mg/cm2, T-score -2.34±1.0. Of which 5 patients (9.6%) were inside normal ranges, 26 (50%) within osteopenia ranges and 21 (40.4%) within osteoporosis ranges. Of these patients with osteoporosis, 11 (21%) had a history of bone fracture. Calculating the risk of fracture in 10 years with FRAX, this was of 7.77±6.713, when added the T-score, the risk of fracture was 13.72±12. The values of osseous alkaline phosphatase were in average 59.40±27.32 and of 25-hidroxivitamin D 14.44±12.4.

In our population, a higher prevalence of cholestasis diseases was found in women and the viral aetiology in men. (P=0.006). Alcohol consumption, viral infection, autoimmune disease, cholestatic origin, NASH or cryptogenic or were not correlated risk factor for hepatic osteodystrophy. In the cluster analysis according values MELD or Child no correlation was found with increased risk of FRAX. (r2=0.187 and 0.115; P=0.18 and 0.41 respectively).

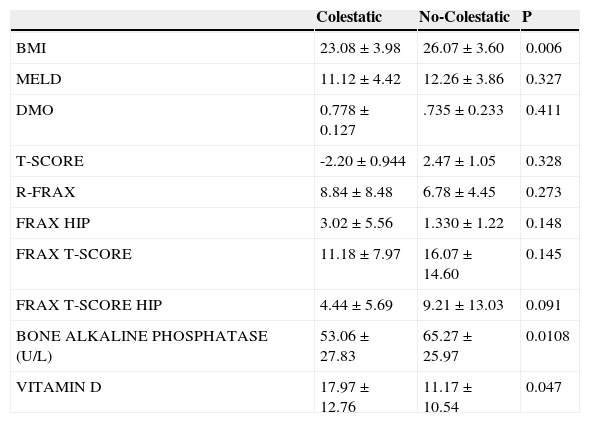

Because in several publications there is a higher prevalence in aetiology cholestasis, an analysis by aetiology was carried out, finding a highly significant relation between aetiology cholestasis and T-score, osseous alkaline phosphatase, age and FRAXs, with T-Score (P<0.05). Analysis by aetiology did not show differences in the values of osseous mineral density, T-score and risk FRAXs.

The IMC was lower in patients with hepatopathy caused by cholestasis than other reasons with a relevant difference (P=0.006). The levels of vitamin D were the lowest in patients with non-cholestasis hepatopathies (P=0.047) and a tendency to a lower FRAX level can be seen in patients with cholestasis hepatopathy. The findings in groups of cholestasis hepatopathy y non-cholestasis can be seen in Table 1.

Clinical features in hepatopaties by colestatic and no colestatic illness.

| Colestatic | No-Colestatic | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | 23.08±3.98 | 26.07±3.60 | 0.006 |

| MELD | 11.12±4.42 | 12.26±3.86 | 0.327 |

| DMO | 0.778±0.127 | .735±0.233 | 0.411 |

| T-SCORE | -2.20±0.944 | 2.47±1.05 | 0.328 |

| R-FRAX | 8.84±8.48 | 6.78±4.45 | 0.273 |

| FRAX HIP | 3.02±5.56 | 1.330±1.22 | 0.148 |

| FRAX T-SCORE | 11.18±7.97 | 16.07±14.60 | 0.145 |

| FRAX T-SCORE HIP | 4.44±5.69 | 9.21±13.03 | 0.091 |

| BONE ALKALINE PHOSPHATASE (U/L) | 53.06±27.83 | 65.27±25.97 | 0.0108 |

| VITAMIN D | 17.97±12.76 | 11.17±10.54 | 0.047 |

During the revision of the expedients very few patients had studies that evaluated the osseous metabolism (osseous alkaline phosphatase, 25-hidroxivitamin D, DMO and parathyroid hormone) probably because there is no established criteria during the evaluation of cirrhotic patients to assess osseous disease. All this contributes to the pathology osteodystrophy is undervalued in the cirrhotic patient. Particularly in the case of our hosptalaria Institution, besides; DO is not available. Most of our patients had a diagnosis of cholestatic diseases (48.1%), this most likely because there are specific guidelines for primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis where indicated finding conduct BMD or osteopenia osteoporosis and initiate appropriate treatment. 18-20 However, in our study we found no correlation between the different causes of cirrhosis and increased risk of fracture, probably due to the small sample size with which we, therefore, should be looking to expand the sample size to find associated risk factors. It is known that the risk of fracture in women over 50 years is 39% and men 13%.18 DO was also identified with T-score -2.5 or less in 21% of white women, women Mexico-American and 16% African American 10% and 20% of patients with vertebral fracture posmenoupáusicas.3,5,19 In our study, 73% were women, many of them postmenopausal, these factors could constitute a bias for themselves increase the risk for bone disease in our patients. On the other hand, particularly in cirrhotic patients, factors such as female gender and older than 50 years should be considered as probable indications for bone disease finding in cirrhotic patients regardless of etiology it. The gravity of the illness was measured in respect to MELD. In general MELD was of 11.71, which indicates that the patients have a mortality of 6% in 3 months. This model was created for the assignment of organs in liver transplant.20 Using the prognosticated value of Child, the majority (40.4%) reached Child C criteria with survivability of 45% in a year and of 35% in 2 years, this reflects the severity of illness of our patients; however, no correlation between the severity of disease or MELD Child with FRAX risk was found, perhaps this may be secondary to our small sample size.

Hepatic osteodistrophy (defined as any osseous disease in patients with advanced hepatic illness)21 was found in the 90.4% of our population. This prevalence is higher than reported in literature in almost 50%.22,23 26 patients were classified with osteopenia (50%) and 21 with osteoporosis (40.4%). These findings in the diagnosis of hepatic osteodistrophy, show that a minimum of 90% of the patients must be under treatment and vigilance to prevent fractures.

In the cirrhotic patients the FRAX calculated a fracture risk of 7.77%±6.713% without taking into account DO data. If added, the T-score data by DO raise the risk to 13.72%±12.03%. It should be noted that there is no previous literature that calculates the FRAX risk in patients with hepatic cirrhosis, making these findings notably valuable. Because the reported prevalence in cholestasis aetiology is higher24, in our study a highly significant relation between cholestasis aetiology with T-score, osseous alkaline phosphatase, age and FRAX with T-score was found. On the other hand, different studies have demonstrated that cirrhosis, caused by cholestasis aetiologies, is associated to a higher risk to suffer of osteodistrophy (37%).25,26 In our population the patients with cholestasis aetiology possess higher levels of vitamin D when compared to other cirrhosis causes (p=0.047). Probably reflecting a deficit of this vitamin in cirrhotic patients for other causes such as alcohol.

In our study the FRAX risk increase was associated with advanced age. This relation can be supported by significant statistic results.

Currently it is unknown the cut point of the FRAX risk at which osteoporosis treatment should begin. Comparing the fracture risk to 10 years of a healthy patient of 0.10% with the average risk of our population of 7%, it could be suggested the realization of a DO to value treatment and continuous vigilance of hepatic osetodistrophy, given a risk, calculated in cirrhotic patients, using a FRAX index higher than 2.

This is the first work where the use FRAX index is proposed as a fracture risk mark to 10 years in patients with hepatic cirrhosis of any aetiology. More studies are needed to continue the validation of this tool.

ConclusionsThis study shows the frequency of hepatic osteodistrophy of 90.4% in a sample of Mexican patients with hepatic cirrhosis of different aetiologies, attending to the Hospital General de México. There are no differences in the prevalence of hepatic osteodistrophy between the different causes of cirrhosis. The levels of osseous alkaline phosphatase and of 25-hidroxivitamin D correlated with the risk of hepatic osteodistrophy in patients with cholestasis aetiology. The most important thing should be the identification of patients in which the loss of life quality or incapacity can be prevented. Because of the findings of this study, a fracture risk to 10 year calculated in the first contact interview of cirrhotic patients with the FRAX tool, a value higher than 2, in the aforementioned index, could be proposed as a cohort point to be followed by DO and to start a scheme of vigilance and treatment.