Tilapia production is considered an alternative to increasing the income of the rural population, and in recent years has surpassed traditional agricultural and livestock activities, playing a fundamental role in food production at the national and global level. The State of Hidalgo has significant aquaculture production; however, there are no previous records related to the microorganisms present. Therefore, this study aimed to identify bacteria that cause foodborne diseases or are associated with human diseases, present in Tilapia in the State of Hidalgo. Sixty-nine isolates were obtained from a collection recovered from a sampling previously conducted in different municipalities of Hidalgo and from different Tilapia organs. Once the isolates were activated, DNA extraction was obtained and molecular identification was performed using the rpoD or 16S rRNA genes, and later sequenced by the Sanger method. Twelve genera and 19 species were identified: Aeromonas (40.6%), Shewanella (14.5%), Acinetobacter (8.7%), Citrobacter, Comamonas, Plesiomonas, Pseudomonas, and Vibrio (5.8%), Kosakonia (2.9%) and Exiguobacterium, Glutamicibacter and Pantoea (1.4%). In this study, various isolates of health importance were identified, because 66.7% of the bacteria found have been associated with foodborne diseases, which can mainly affect immunosuppressed or immunocompetent individuals. This study reveals the presence of pathogens in a highly consumed product; therefore, it is necessary to implement strategies to reduce the presence of these pathogens of public health importance.

La producción de tilapia ha permitido incrementar los ingresos de la población rural en ciertas áreas de México y, en los últimos años, ha superado a las actividades agrícolas y pecuarias tradicionales, jugando un papel fundamental en la producción de alimentos a nivel nacional y mundial. En el estado de Hidalgo (México) existe una importante producción acuícola; sin embargo, no hay registros relacionados con la presencia de microorganismos en este producto. Por lo tanto, este estudio tuvo como objetivo identificar bacterias causantes de enfermedades transmitidas por alimentos, o asociadas a enfermedades en humanos, en ejemplares de tilapia en el estado de Hidalgo. Se obtuvieron 69 aislamientos de una colección recuperada de un muestreo realizado con anterioridad en diferentes municipios de dicho estado y a partir de diferentes órganos de tilapia. Una vez activados los aislamientos, se extrajo el ADN y se realizó la identificación molecular utilizando los genes rpoD o 16s ARNr; posteriormente se secuenciaron por el método de Sanger. Se identificaron 19 especies distribuidas en los siguientes 12 géneros: Aeromonas (40,6%), Shewanella (14,5%), Acinetobacter (8,7%); Citrobacter, Comamonas, Plesiomonas, Pseudomonas y Vibrio (5,8%); Kosakonia (2,9%) y Exiguobacterium, Glutamicibacter y Pantoea (1,4%). El 66,7% de las bacterias encontradas se han asociado a enfermedades de transmisión alimentaria, que pueden afectar principalmente a personas inmunodeprimidas, aunque también a inmunocompetentes. Este estudio revela la presencia de patógenos en un producto muy consumido, por lo que es necesario implementar estrategias para reducir la carga de patógenos de importancia sanitaria en este producto.

Aquaculture is one of the economic activities with the most significant development and growth in recent decades. Reports from the FAO indicate that there has been an increase in the consumption of foods of aquaculture origin, estimated at 20.7kg per capita, pointing to an increase in apparent consumption of 3% between 1961 and 202147. Tilapia (Oreochromis spp.) enjoys great popularity due to its rapid growth and adaptability to different environments and food sources. However, high concentrations of animals per pond undermine the health status of Tilapia, causing stress, reducing their growth, risking their immune system, and making them susceptible to pathogens present in the environment19. The State of Hidalgo has an active population of 3357 fishermen and about 432 aquaculture production units, producing Tilapia, channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and carp (Cyprinus carpio); among these, Tilapia rank first, accounting for 60.22% of the total production, resulting in 274 tons in live weight for the year 202210. This is marketed through the production units and directly, in local markets, by intermediaries in regional markets and nearby states that demand weight and size, but are less demanding regarding the sanitary quality of the product46. Foodborne diseases (FBDs) are caused by food contamination at any stage of the production, supply, and consumption chain. Their origin is attributed to environmental contamination, storage, and transformation of food, involving any process, from breeding to processing and consumption9, and have been noted as a priority in worldwide public health11. The bacteria that cause diseases are diverse and the genera associated with infections in aquaculture and their derivatives are Aeromonas spp., Streptococcus spp., Staphylococcus spp., Pseudomonas spp., Plesiomonas spp. and Vibrio spp.37. Furthermore, the genera Pseudomonas spp., Aeromonas spp., and Shewanella spp., have been isolated from fillets3,15, and have been identified as causing FBDs. The conditions caused by these genera that have been observed in humans are diverse, ranging from weakness, fever, headache, and mild diarrhea to more serious conditions in immunocompromised individuals or in people suffering from chronic diseases, such as gastroenteritis, septicemia, necrotizing fasciitis and meningoencephalitis18,32. For these reasons and due to the possible risks that they represent for public health, this study aimed to identify pathogenic bacteria with the potential to cause FBDs, isolated from Tilapia raised in municipalities of aquaculture importance in the State of Hidalgo using molecular techniques.

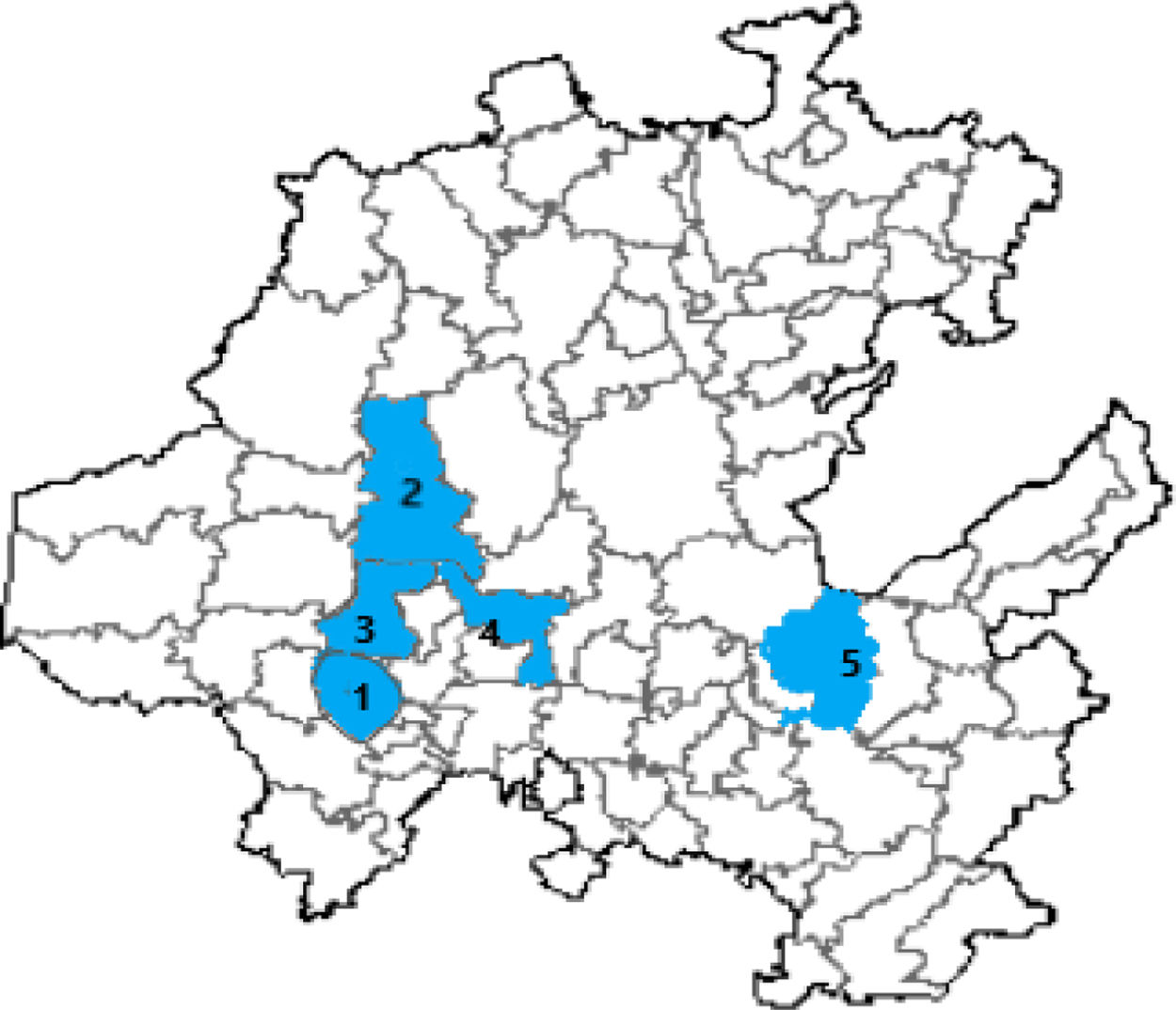

Materials and methodsOrigin of the bacterial isolatesTilapias were captured by the producer in aquaculture production units located in the municipalities of Tezontepec de Aldama (2004 m.a.s.l.), Ixmiquilpan (1680 m.a.s.l.), Progreso de Obregón (1985 m.a.s.l.), Chilcuautla (1864 m.a.s.l.) and Huasca de Ocampo (2089 m.a.s.l.) (Fig. 1). The producer provided 30 specimens, each was assigned a number in progressive sequence and samples were taken from the dorsal, pectoral, ventral, anal and caudal fins, as well as from the intestine, liver, spleen, and kidneys (Tables 1 and 2). For bacteriological isolation, each sample was plated on Trypto-Casein Soy Agar (TSA) (MCD LAB, Tultitlán de Mariano Escobedo, Mexico) and ampicillin-dextrin agar media (HiMedia, India) incubated at 30°C for 24h. Circular, convex, yellow colonies, with 1–3mm in diameter were selected as presumptive Aeromonas spp.11,41. The bacteria used were preserved at −20°C in cryovials containing trypticase soy broth (Difco, BD), with 10% glycerol (PROMEGA), and form part of the strain collection isolated from Tilapia in 2021.

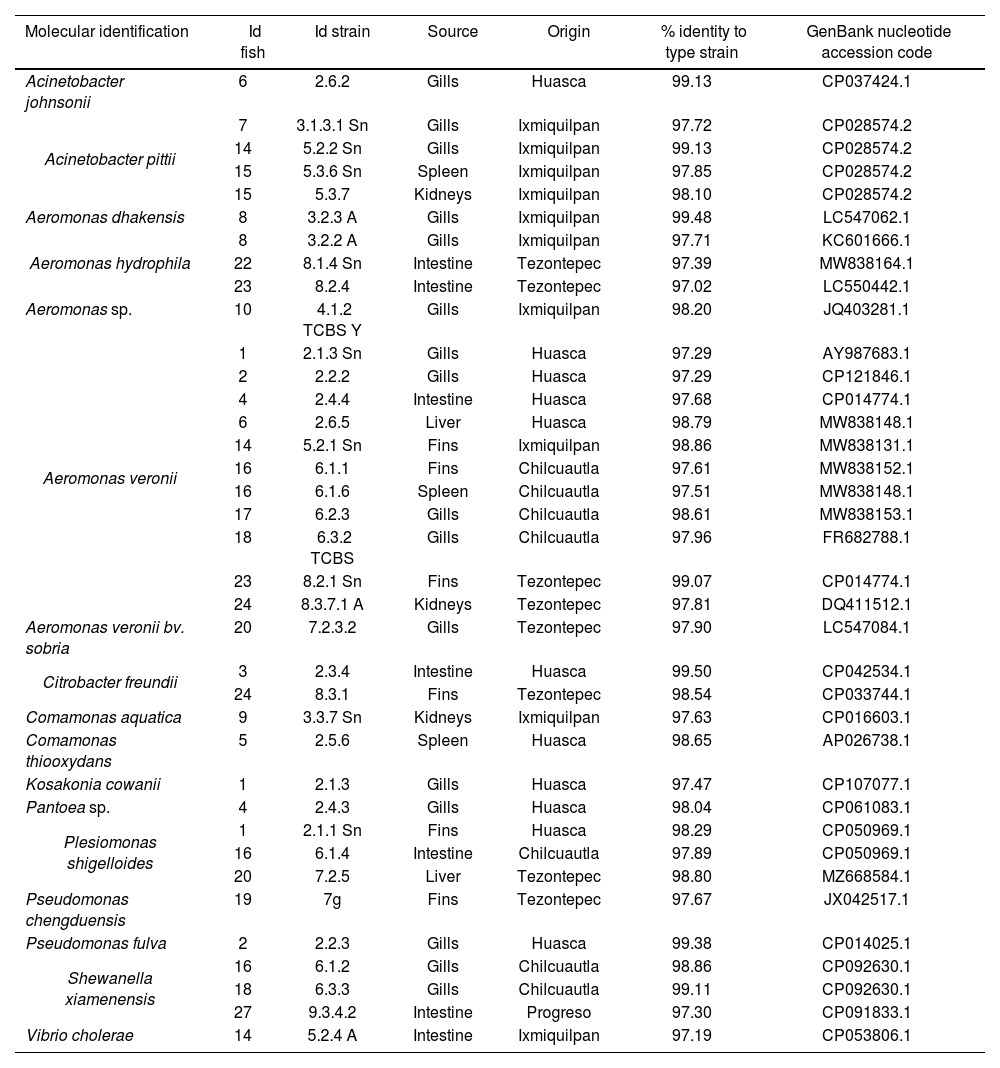

Molecular identification of bacteria isolated from Tilapia (Oreochromis spp.) using the rpoD gene.

| Molecular identification | Id fish | Id strain | Source | Origin | % identity to type strain | GenBank nucleotide accession code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acinetobacter johnsonii | 6 | 2.6.2 | Gills | Huasca | 99.13 | CP037424.1 |

| Acinetobacter pittii | 7 | 3.1.3.1 Sn | Gills | Ixmiquilpan | 97.72 | CP028574.2 |

| 14 | 5.2.2 Sn | Gills | Ixmiquilpan | 99.13 | CP028574.2 | |

| 15 | 5.3.6 Sn | Spleen | Ixmiquilpan | 97.85 | CP028574.2 | |

| 15 | 5.3.7 | Kidneys | Ixmiquilpan | 98.10 | CP028574.2 | |

| Aeromonas dhakensis | 8 | 3.2.3 A | Gills | Ixmiquilpan | 99.48 | LC547062.1 |

| Aeromonas hydrophila | 8 | 3.2.2 A | Gills | Ixmiquilpan | 97.71 | KC601666.1 |

| 22 | 8.1.4 Sn | Intestine | Tezontepec | 97.39 | MW838164.1 | |

| 23 | 8.2.4 | Intestine | Tezontepec | 97.02 | LC550442.1 | |

| Aeromonas sp. | 10 | 4.1.2 TCBS Y | Gills | Ixmiquilpan | 98.20 | JQ403281.1 |

| Aeromonas veronii | 1 | 2.1.3 Sn | Gills | Huasca | 97.29 | AY987683.1 |

| 2 | 2.2.2 | Gills | Huasca | 97.29 | CP121846.1 | |

| 4 | 2.4.4 | Intestine | Huasca | 97.68 | CP014774.1 | |

| 6 | 2.6.5 | Liver | Huasca | 98.79 | MW838148.1 | |

| 14 | 5.2.1 Sn | Fins | Ixmiquilpan | 98.86 | MW838131.1 | |

| 16 | 6.1.1 | Fins | Chilcuautla | 97.61 | MW838152.1 | |

| 16 | 6.1.6 | Spleen | Chilcuautla | 97.51 | MW838148.1 | |

| 17 | 6.2.3 | Gills | Chilcuautla | 98.61 | MW838153.1 | |

| 18 | 6.3.2 TCBS | Gills | Chilcuautla | 97.96 | FR682788.1 | |

| 23 | 8.2.1 Sn | Fins | Tezontepec | 99.07 | CP014774.1 | |

| 24 | 8.3.7.1 A | Kidneys | Tezontepec | 97.81 | DQ411512.1 | |

| Aeromonas veronii bv. sobria | 20 | 7.2.3.2 | Gills | Tezontepec | 97.90 | LC547084.1 |

| Citrobacter freundii | 3 | 2.3.4 | Intestine | Huasca | 99.50 | CP042534.1 |

| 24 | 8.3.1 | Fins | Tezontepec | 98.54 | CP033744.1 | |

| Comamonas aquatica | 9 | 3.3.7 Sn | Kidneys | Ixmiquilpan | 97.63 | CP016603.1 |

| Comamonas thiooxydans | 5 | 2.5.6 | Spleen | Huasca | 98.65 | AP026738.1 |

| Kosakonia cowanii | 1 | 2.1.3 | Gills | Huasca | 97.47 | CP107077.1 |

| Pantoea sp. | 4 | 2.4.3 | Gills | Huasca | 98.04 | CP061083.1 |

| Plesiomonas shigelloides | 1 | 2.1.1 Sn | Fins | Huasca | 98.29 | CP050969.1 |

| 16 | 6.1.4 | Intestine | Chilcuautla | 97.89 | CP050969.1 | |

| 20 | 7.2.5 | Liver | Tezontepec | 98.80 | MZ668584.1 | |

| Pseudomonas chengduensis | 19 | 7g | Fins | Tezontepec | 97.67 | JX042517.1 |

| Pseudomonas fulva | 2 | 2.2.3 | Gills | Huasca | 99.38 | CP014025.1 |

| Shewanella xiamenensis | 16 | 6.1.2 | Gills | Chilcuautla | 98.86 | CP092630.1 |

| 18 | 6.3.3 | Gills | Chilcuautla | 99.11 | CP092630.1 | |

| 27 | 9.3.4.2 | Intestine | Progreso | 97.30 | CP091833.1 | |

| Vibrio cholerae | 14 | 5.2.4 A | Intestine | Ixmiquilpan | 97.19 | CP053806.1 |

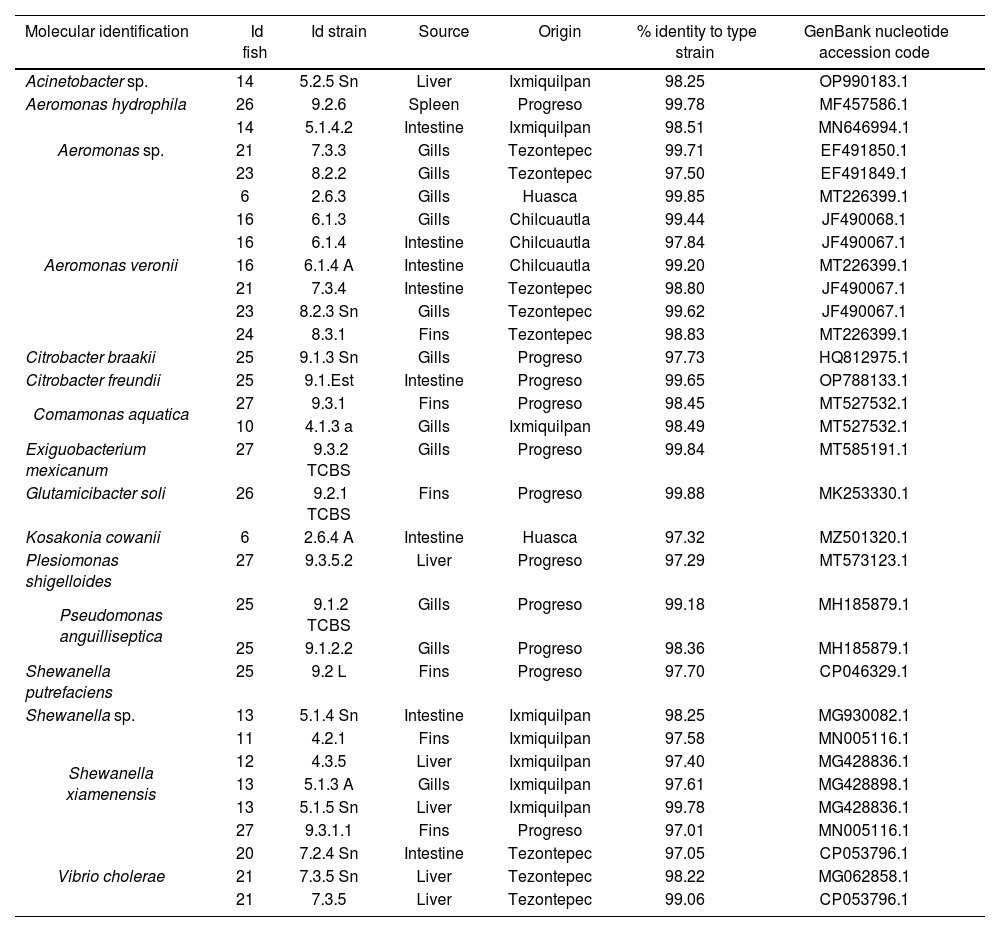

Molecular identification of bacteria isolated from Tilapia using the 16S rRNA gene.

| Molecular identification | Id fish | Id strain | Source | Origin | % identity to type strain | GenBank nucleotide accession code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acinetobacter sp. | 14 | 5.2.5 Sn | Liver | Ixmiquilpan | 98.25 | OP990183.1 |

| Aeromonas hydrophila | 26 | 9.2.6 | Spleen | Progreso | 99.78 | MF457586.1 |

| Aeromonas sp. | 14 | 5.1.4.2 | Intestine | Ixmiquilpan | 98.51 | MN646994.1 |

| 21 | 7.3.3 | Gills | Tezontepec | 99.71 | EF491850.1 | |

| 23 | 8.2.2 | Gills | Tezontepec | 97.50 | EF491849.1 | |

| Aeromonas veronii | 6 | 2.6.3 | Gills | Huasca | 99.85 | MT226399.1 |

| 16 | 6.1.3 | Gills | Chilcuautla | 99.44 | JF490068.1 | |

| 16 | 6.1.4 | Intestine | Chilcuautla | 97.84 | JF490067.1 | |

| 16 | 6.1.4 A | Intestine | Chilcuautla | 99.20 | MT226399.1 | |

| 21 | 7.3.4 | Intestine | Tezontepec | 98.80 | JF490067.1 | |

| 23 | 8.2.3 Sn | Gills | Tezontepec | 99.62 | JF490067.1 | |

| 24 | 8.3.1 | Fins | Tezontepec | 98.83 | MT226399.1 | |

| Citrobacter braakii | 25 | 9.1.3 Sn | Gills | Progreso | 97.73 | HQ812975.1 |

| Citrobacter freundii | 25 | 9.1.Est | Intestine | Progreso | 99.65 | OP788133.1 |

| Comamonas aquatica | 27 | 9.3.1 | Fins | Progreso | 98.45 | MT527532.1 |

| 10 | 4.1.3 a | Gills | Ixmiquilpan | 98.49 | MT527532.1 | |

| Exiguobacterium mexicanum | 27 | 9.3.2 TCBS | Gills | Progreso | 99.84 | MT585191.1 |

| Glutamicibacter soli | 26 | 9.2.1 TCBS | Fins | Progreso | 99.88 | MK253330.1 |

| Kosakonia cowanii | 6 | 2.6.4 A | Intestine | Huasca | 97.32 | MZ501320.1 |

| Plesiomonas shigelloides | 27 | 9.3.5.2 | Liver | Progreso | 97.29 | MT573123.1 |

| Pseudomonas anguilliseptica | 25 | 9.1.2 TCBS | Gills | Progreso | 99.18 | MH185879.1 |

| 25 | 9.1.2.2 | Gills | Progreso | 98.36 | MH185879.1 | |

| Shewanella putrefaciens | 25 | 9.2 L | Fins | Progreso | 97.70 | CP046329.1 |

| Shewanella sp. | 13 | 5.1.4 Sn | Intestine | Ixmiquilpan | 98.25 | MG930082.1 |

| Shewanella xiamenensis | 11 | 4.2.1 | Fins | Ixmiquilpan | 97.58 | MN005116.1 |

| 12 | 4.3.5 | Liver | Ixmiquilpan | 97.40 | MG428836.1 | |

| 13 | 5.1.3 A | Gills | Ixmiquilpan | 97.61 | MG428898.1 | |

| 13 | 5.1.5 Sn | Liver | Ixmiquilpan | 99.78 | MG428836.1 | |

| 27 | 9.3.1.1 | Fins | Progreso | 97.01 | MN005116.1 | |

| Vibrio cholerae | 20 | 7.2.4 Sn | Intestine | Tezontepec | 97.05 | CP053796.1 |

| 21 | 7.3.5 Sn | Liver | Tezontepec | 98.22 | MG062858.1 | |

| 21 | 7.3.5 | Liver | Tezontepec | 99.06 | CP053796.1 |

The strains were subjected to thermal shock following the methodology of Reyes-Rodríguez41. A bacterial colony was suspended in 1ml of sterile distilled water and washed by centrifugation. Subsequently, the bacterial pellet was suspended in 200μl of sterile distilled water, incubated at 100°C for 5min and frozen in a block of ice for 5min, repeating the cycle three times. Finally, they were centrifuged for 10min at 10000rpm. The supernatant was quantified using a spectrophotometer (Nanodrop ND-100, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., US) and stored at −20°C until use.

Enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus-PCRFor the ERIC-PCR test, the primers used were ERIC-1R (5′-ATGTAAGCTCCTGGGGATT CAC-3′) and ERIC-2 (5′-AAGTAAGTGACTGGG GTGAGCG-3′)48. The technique was performed using a mix adjusted for a final volume of 50μl. Master Mix 2X (Promega, Wisconsin, USA) (1×) Taq (0.625U), dNTPs (200μM) and MgCl2 (1.5mM), primer forward and reverse (10μM) and DNA (15ng) were used, it was optimized with MgCl2 (1mM) and Taq Polymerase (GoTaq, Gentaq) (0.375U). The amplification cycles used were: an initial denaturation at 94°C for 5min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation (1min at 94°C), hybridization (1min at 52°C), extension (6min at 74°C), and final extension at 74°C for 6min. Ten microliters of 5X Green Go Taq (Promega, USA) were added to the amplified products and observed on a 1.5% agarose gel (Invitrogen) previously prepared with 4μl of ethidium bromide. Fourteen wells were prepared in each gel. The 100bp DNA ladder marker occupied two wells, and a positive control was included. Samples were loaded accordingly, and electrophoresis was performed in a THERMO CE chamber (Massachusetts, USA) for 120min at 80V and 400mA. Gel images were captured for subsequent analysis using GelJ software. The isolates were clustered using the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) analysis and the dice similarity coefficient.

Sequencing identificationTo identify the isolates, sequences of the rpoD and 16S rRNA genes were analyzed based on the similarity percentage of the type strains for each gene and the position of the sequences in the phylogenetic analysis. The rpoD gene was amplified with the primers reported by Reyes-Rodríguez41. The PCR reaction included 5μl of 10× PCR Go-Taq reaction mix (50mM KCl, 75mM Tris–HCl, pH 9.0, 2mM MgCl2; Promega), 1μl of 10mM dNTP mix, 0.5μl of Taq DNA polymerase (5U/μL; Promega), 1μl of 10mM of each primer, and 5μl of DNA, adjusted to a final volume of 50μl. The conditions were as follows: 95°C for 5min followed by two cycles at 94°C for 1min, 63°C for 1min (hybridization), 72°C for 1min, two cycles at 94°C for 1min, 61°C for 1min, 72°C for 1min, two cycles at 94°C for 1min, 59°C for 1min, 72°C for 1min, 30 cycles at 94°C for 1min, 58°C for 1min, 72°C for 1min44. The amplified products (830bp) were observed on a 1.5% agarose gel (Invitrogen), placed in an electrophoresis chamber under the following conditions: 80V, 400mA for 50min; those that tested negative were subjected to PCR amplification of 16S ribosomal RNA.

Fragments of the 16S rRNA gene were amplified using the universal primers described by Borrell2. The PCR reaction included 10μl 5X GoTaq® Flexi Reaction Buffer (Promega, Wisconsin, USA), 1μl dNTP mix, 1.25U (0.25μl) Taq DNA polymerase, 35.75μl nuclease-free water, 1μl of each primer and 1μl of DNA, adjusted at a final volume of 50μl, the presence of a 1503bp amplicon was verified on 1.5% agarose gels under conditions similar to those described above and time was reduced to 45min. The conditions in the thermocycler were: initial denaturation for 3min at 93°C, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation for 1min at 95°C, annealing for 1min at 56°C, and extension for 1min at 72°C. Final extension for 10min at 72°C for 10min. The amplified products (1503bp) were observed a 1.5% agarose gel placed in an electrophoresis chamber, under the conditions described previously.

The amplified products were purified using the Wizard® SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System kit (Promega, #A9281, Wisconsin, US). They were sequenced by the Sanger method at the National Laboratory of Genomics for Biodiversity of the Center for Research and Advanced Studies of the National Polytechnic Institute, Mexico. The sequences obtained were assembled using the MEGA 11 software (https://www.megasoftware.net) and compared in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database using the BLAST tool. The nucleotide sequences of the strains identified were aligned using the ClustalW program including the published sequences for the type strains. Genetic distances were obtained using the Kimura's two-parameter model26. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining method43 using the MEGA 11 software.

Results and discussionIn this study, 69 bacteria isolated from Tilapia (Oreochromis spp.) from the State of Hidalgo were identified at distinct developmental stages and in unaltered organs. Genera identified were Aeromonas 40.6% (28/69), Shewanella 14.5% (10/69); Acinetobacter 8.7% (6/69), Citrobacter, Comamonas, Plesiomonas, Pseudomonas and Vibrio 5.8% each (4/69), Kosakonia 2.9% (2/69); Exiguobacterium, Glutamicibacter and Pantoea 1.4% each (1/69). The organs with the highest percentage of isolations were the gills 39.1% (27/69), followed by the intestine 21.7% (15/69), fins 17.4% (12/69), liver 10.1% (7/69), spleen 7.3% (5/69) and kidneys 4.4% (3/69) (Tables 1 and 2).

The ERIC-PCR test allowed us to make a first filter among the strains, as we obtained 6 clusters (A, B, C, D, E and F), from which we selected a strain from each one, considered to be the “representative” strain. Following the molecular identification, we found that each cluster corresponded to different strains of Aeromonas sp., Aeromonas veronii, Shewanella xiamenensis, Plesiomonas shigelloides, and Acinetobacter johnsonii (supplementary material).

The genus with the highest presence was Aeromonas, specifically A. veronii 64.3% (18/28) Aeromonas sp., and A. hydrophila 14.3% each (4/28), A. dhakensis and A. veroniibv.sobria. It is a Gram-negative pathogen with coccobacillary morphology, usually found in aquatic environments, capable of affecting a wide variety of species, domestic animals, frogs, reptiles, freshwater, and saltwater fish, and considered an opportunistic human pathogen capable of affecting immunocompromised and immunocompetent individuals21. It has also been isolated from different food sources. Therefore, it is regarded as an emerging pathogen and a public health risk as a result of the multiple reports of its presence in raw, lightly processed foods on display and ready for consumption23, due to its ability to survive and multiply at low temperatures15. Members of the Aeromonas genus are known pathogens in global aquaculture; A. hydrophila, A. veronii, A. sobria, A. dhakensis, A. jandei have been found in both healthy and sick fish, spreading due to stressful breeding and handling conditions that compromise the immune system8, allowing the passage of bacteria to internal organs. A. caviae, A. piscicola, A. veronii, A. dhakensis, A. hydrophila, A. schubertii, and A. trota are also reported as disease-causing species in humans11, accounting for 96% of gastroenteritis cases. A. veronii is a public health risk and several outbreaks associated with food of aquatic origin have been reported, for example, disease was reported from consumed fish in China31, while a high prevalence of A. veronii was observed in adult diarrhea cases in a hospital in Taiwan7. This genus causes gastroenteritis, septicemia, hepatobiliary tract and pleuropulmonary infections, meningitis, peritonitis, and hemolytic uremic syndrome by food consumption or by direct contact with immunocompromised persons41. The presence of this genus in Tilapia (Oreochromis spp.) represents a problem for human health.

Isolates of Shewanella sp., S. xiamenensis and S. putrefaciens were also identified. They were found in the fins, intestines, liver, and gills. The Shewanella genus, which are Gram-negative bacilli are widely distributed in aquatic environments, sediments, and soils6. S. putrefaciens is a halophilic bacterium of great relevance in the food industry, due to its ability to survive refrigeration temperatures, causing putrefaction of meat from aquaculture, poultry, or bovine sources37. Reports indicate that S. putrefaciens, among S. xiamenensis, and S. algae are a growing threat to human health, causing skin and soft tissue infections, bacteremia, otitis, and hepatobiliary infections. S. putrefaciens can adapt to different niches, thereby facilitating the acquisition of a wide variety of mobile elements; thus, it is considered a reservoir of resistance genes because it participates in the dissemination of antimicrobial resistance6. This pathogen can be a threat because it was identified from tilapias intended for human consumption, and inadequate management can lead to possible consequences for health.

The genus Acinetobacter consists of Gram-negative coccobacilli, ubiquitous in nature and present in soils, bodies of water, drinking water, various foods, and nosocomial environments5. In this study we identified six isolates of this genus. A. pitti, which causes diseases in fish and humans, is highly prevalent in nosocomial environments30, while A. johnsonii, an emerging pathogen in aquaculture, has been associated with cases of bacteremia in humans28.

Pseudomonas is an opportunistic freshwater and saltwater fish pathogen and a serious threat to the aquaculture industry38. The genus is widely distributed in soils, plants, and animals due to its low survival and adaptability requirements. In this study, P. chengduensis, P. fulva and P. anguilliseptica were identified. P. fulva has been isolated from wetlands, rice plantations, plants, and oil soils40; however, cases of infection in humans are rare, typical of nosocomial origin, and associated with trauma, ventricular drainage, or transfusions using contaminated equipment27.

Vibriosis is a disease caused by different members of the genus Vibrio, Gram-negative bacilli resulting in high mortality rates and significant losses in the aquaculture sector, most members of this genus are opportunistic pathogens22. Vibrio cholerae can be isolated from aquatic environments, especially in warm months16. The consumption of raw or poorly cooked seafood and fillets causes in humans profound dehydration, dysentery, and in some cases extraintestinal diseases such as meningitis, septicemia, acute diarrhea, and in particular cases, death50; however, only the strains of serogroups O1 and O139 cause cholera epidemics, although some non-O1/O139 strains can produce heat stable toxins and cause septic infections17,32. In this study four isolates were identified; nonetheless, in Mexico the regulations specify that it should be absent in this type of products, considering that it is regarded as a worldwide threat to public health.

Plesiomonas shigelloides is the only species of the genera, in which only four isolates were identified. This genus is a Gram-negative bacillus with a wide distribution in water and has been isolated from terrestrial and aquatic mammals, fish, mollusks, crustaceans, amphibians, reptiles, and birds24. Infection in humans is mainly associated with the consumption of raw or undercooked fish and shellfish and causes gastrointestinal and extraintestinal illnesses, usually causing chills, fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting, cellulitis, meningitis, urinary tract infections, and, in severe cases, profuse diarrhea and septicemia12.

Comamonas spp. comprises species of Gram-negative bacilli49; Citrobacter is a genus belonging to the Enterobacteriaceae family, comprising Gram-negative bacilli20. Four isolates were identified in each of the two genera, and both are usually found in soils, bodies of water, water used in airplanes, plants, and as commensals in the digestive system of pets, birds, and domestic animals, in addition to the respiratory and urinary tracts of humans29. They are considered opportunistic pathogens33. Comamonas kerstersii, Comamonas aquatica, Comamonas thiooxydans, and Comamonas terrigena have been reported as causing infection in immunocompromised individuals42.

Kosakonia cowanii (previously known as Enterobacter cowanii) and Pantoea sp. are pathogens isolated mainly from plants, soils, and rarely in infant formulas and healthcare facilities. Few cases of infections in humans have been reported, mainly occurring in newborns or in individuals with chronic diseases1,34. The genus Exiguobacterium has variable morphology (ranging from small bacilli to cocci), is Gram negative, and can be isolated from various environments such as soils, sediments, permafrost, glaciers, industrial waters, and hydrothermal vents, it is not considered pathogenic25. Exiguobacterium mexicanum was isolated for the first time from Artemia spp. larvae35 and has shown no pathological potential. Glutamicibacter soli belongs to the genus Glutamicibacter. It has been isolated from wastewater, soil, human urine, roots, and from the fly Protophormia terraenovae4.

All identified genera are usually found in water, sediments, or soil near aquaculture farms; however, Aeromonas, Vibrio, Plesiomonas, Pseudomonas, and Shewanella are not only pathogenic for fish but also considered threats to human health6,11,12. Their presence in the skin, gills, intestines, spleen, and kidneys facilitates the subsequent colonization of the fillet since the muscle is considered sterile until the death of the fish. These bacteria can migrate due to ulcerative lesions, potentially resulting in septicemic processes, both at the time of the fish death and during the handling processes to obtain the fillet3. If ingested raw, lightly, or inadequately cooked, it can cause FBDs9. This agrees with the findings reported in our study, hence the bacteria identified with the highest prevalence were found in fins and gills, followed by the intestine. Foysal19 demonstrated high prevalence of pathogens such as Vibrio cholerae, Aeromonas spp., Acinetobacter spp., Staphylococcus spp., Streptococcus spp., Mycobacterium, and Escherichia-Shigella found in both the skin and intestine of fish intended for human consumption sold in local markets and in shopping malls in Bangladesh. Sripradite45 also reported the presence of Aeromonas hydrophila, Salmonella sp. and Vibrio cholerae in fillet, intestine, liver, and kidneys of Tilapia sold fresh, displayed on ice and shopping centers. These microorganisms can persist in undercooked or raw preparations, as reported by Park36, who demonstrated the prevalence of A. hydrophila in sushi samples (20–51.4%) obtained from shopping centers and restaurants. Li32 showed the presence of V. cholerae (3.8%) among other pathogens, in different fish purchased from farms, restaurants, supermarkets, and online stores; Díaz-Cárdenas14 found the genera Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, Vibrio, Aeromonas and Citrobacter in ceviche samples, showing that these bacteria are capable of surviving different preparation processes. In addition, it should be considered that many of the gastrointestinal conditions caused by these bacteria can go unnoticed and may not be accurately diagnosed, particularly when appropriate follow-up is lacking, a situation that is further aggravated when vulnerable populations are involved, and where dehydration could trigger serious clinical conditions.

Surveillance, prevention, and management measures play an essential role, as some of the bacteria identified in this study have multiple characteristics that could affect more than one sector, and cause various types of diseases. As mentioned previously, all the identified genera are usually found in diverse environments. Aeromonas, Shewanella, Vibrio, and Pseudomonas are classified as food spoilage organisms affecting food quality13; Aeromonas, Plesiomonas, and Vibrio are considered bacteria with zoonotic potential worldwide39,50. Furthermore, there is growing evidence pointing to Aeromonas, Pseudomonas, Plesiomonas, Acinetobacter, Vibrio, and Citrobacter as genera exhibiting antimicrobial resistance and potentially serving as reservoirs of antibiotic resistance genes18,27,38,39,45.

In Mexico, Tilapia is consumed primarily cooked or fried, which significantly reduces its microbial load. However, several studies have documented the presence of pathogenic bacteria in aquaculture production systems, which represents a potential risk to public health12,31.32. Microbiological analyses performed on non-edible tissues, such as skin, gills, intestines, and culture water, have identified microorganisms such as Salmonella spp., Aeromonas spp., Vibrio spp., Plesiomonas spp. and Escherichia coli, which are recognized foodborne pathogens9,11,12,14,21,32. These bacteria can be transferred to the edible muscle of fish due to poor hygiene practices during the capture, filleting, transportation or storage stages, as well as due to injuries to the fish or unhealthy conditions of the culture water15,37. Furthermore, subsequent inadequate practices, such as poor refrigeration, cross-contamination, or the preparation of semi-raw dishes, such as ceviches or pickles, can compromise the safety of the final product, especially in vulnerable populations such as immunocompromised individuals, young children, and older adults12,21. Therefore, the detection of pathogens in Tilapia external matrices constitutes a significant health alert regarding hygiene and sanitation deficiencies in production systems, which must be addressed to reduce the risk of contamination of the final product intended for human consumption. Although studies that do not include muscle analysis do not allow direct estimation of consumer risk, they provide sufficient evidence to justify corrective measures in production and handling practices.

ConclusionThis study demonstrated the presence of microorganisms, such as Aeromonas, Shewanella, Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, Vibrio, and Plesiomonas, among others, obtained from Tilapia cultured in the State of Hidalgo. The possible presence of these microorganisms is attributed to their ubiquity and wide distribution in the environment, as well as to the biological composition of fish, which makes them susceptible to contamination. These microorganisms can affect various species and be transmitted throughout the production process, causing various diseases. For all these reasons, further research is needed to design and implement surveillance, control, and other measures to prevent or mitigate risks to public health.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

The authors would like to thank the economic support provided by the Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencias y Tecnologías (CONAHCYT), Beca de Estimulo Institucional de Formación de Investigadores (BEIFI), Instituto Politécnico Nacional (IPN).