Edited by:

Diego Sauka - Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Argentina

Leopoldo Palma - Universidad de Valencia, Spain

Johannes Jehle - Julius Kühn-Institut, Institute for Biological Control, Germany

Last update: October 2025

More infoSpecies of the genus Streptomyces are a promising strategy for bacterial disease management in agriculture crops. The present study aimed to isolate and identify Streptomyces-like actinobacteria from rhizospheric soil using physical pretreatments and to evaluate their antimicrobial activity against Xanthomonas sp. A rhizospheric soil from a bean plantation was pretreated using dry heat or microwave radiation for isolating actinobacteria. Antimicrobial activity was evaluated using the double agar layer method; 73 isolates exhibiting Streptomyces colony characteristics were obtained from the soil after dry heat pre-treatment series (50 BVBZ) and microwaves (23 BVBZMW); 34 BVBZ (68%) isolates inhibited Xanthomonas sp. growth with 11.2–35.8mm halos in diameter. Fifteen (15) of 23 BVBZMW isolates (65%) recorded inhibition zones ranging from 15.7 to 73.6mm in diameter. The 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis confirmed three isolates with greater antimicrobial activity belonging to the genus Streptomyces. Streptomyces sp. BVBZ 35, BVBZ 47, and BVBZMW 18 shared greater 16S rRNA gene sequence identity with S. monomycini NRRL B-2409T (100%), S. nogalater JCM 4799T (99.38%) and S. leeuwenhoekii C34T (99.45%), respectively. Streptomyces sp. BVBZMW 18, which exhibited the highest antimicrobial activity, could only be cultured after microwave irradiation of the soil. Streptomyces species isolated from rhizospheric soil using physical pretreatments are a potentially novel antimicrobial source for Xanthomonas disease control.

Las especies del género Streptomyces son una prometedora estrategia para el manejo de enfermedades bacterianas en cultivos agrícolas. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo aislar e identificar actinobacterias tipo Streptomyces de suelo rizosférico luego de aplicar pretratamientos físicos y evaluar su actividad antimicrobiana contra Xanthomonas sp. El suelo rizosférico de una plantación de frijol, pretratado con calor seco o radiación electromagnética con microondas, se usó para aislar las actinobacterias. La actividad antimicrobiana de los aislados se evaluó por el método de la doble capa de agar. Se obtuvieron 73 aislados con las características coloniales de Streptomyces luego de los pretratamientos de calor seco (n=50, serie BVBZ) y de microondas (n=23, serie BVBZMW). Treinta y cuatro aislados de la serie BVBZ (68%) y 23 aislados BVBZMW (65%) inhibieron el crecimiento de Xanthomonas sp., con halos de inhibición de 11.2 a 35.8mm y 15.7 a 73.6mm de diámetro, respectivamente. El análisis de la secuencia del gen ARNr 16S confirmó que los tres aislados con mayor actividad antimicrobiana correspondían al género Streptomyces. Los aislamientos BVBZ 35, BVBZ 47 y BVBZMW 18 compartieron la mayor identidad de secuencia (ARNr 16S) con Streptomyces monomycini NRRL B-24309T (100%), Streptomyces nogalater JCM 4799T (99.38%) y Streptomyces leeuwenhoekii C34T (99.45%), respectivamente. Streptomyces sp. BVEZMW 18 fue el aislado que exhibió la mayor actividad antimicrobiana y solo pudo cultivarse después de la irradiación del suelo con microondas. Las especies de Streptomyces aisladas de suelo rizosférico luego de pretratamientos físicos son una fuente de antimicrobianos potencialmente novedosos para controlar enfermedades provocadas por Xanthomonas.

Mexico is the third chili pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) producer at world level and the second vegetable producer at national level with 3 million 681 thousand tons in 202346. Exports of this agricultural product generated USD 1231 million in 202346 profits. Chili, like other economically important cultivars, is affected by diseases caused by phytopathogenic organisms that decrease their productivity32. Bacterial spot is one of the diseases that mostly affect chili cultivars, caused by four Xanthomonas biotypes: X. vesicatoria, X. euvesicatoria pv. euvesicatoria, X. euvesicatoria pv. perforans and X. hortorum pv. gardneri52. In Mexico, bacterial spot in chili has been reported to affect commercial plantations in states such as Jalisco, Zacatecas, Michoacán, and Chihuahua15,26. Bacterial spot is estimated to cause losses of about 30–66% in crop yield, including higher numbers if the environmental conditions are favorable for the pathogen8,42. Disease control is based on the continuous use of agrochemicals based on copper or antibiotics, whose indiscriminate use has caused the survival of resistant strains, thus requiring new products for disease management3,15.

Bacterial biocontrol agents or their bioactive compounds have been reported as potential alternatives for managing diseases caused by Xanthomonas spp.27,31. The bacterial genus Streptomyces is known to be a source of natural bioactive compounds with antibacterial, anti-biofilm, enzymatic or quorumsensing inhibitors, among others6,20. Moreover, this genus is widely distributed in terrestrial and aquatic environments, with terrestrial environments containing the greatest percentage of new species (80%) and natural products (60%) found from 2015 to 20226.

Streptomyces spp. has been reported to be a biological control agent against bacterial diseases, such as the halo blight of beans caused by Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola3, the pineapple white rot caused by Dickeya zeae1, the bacterial panicle blight of rice caused by Burkholderia glumae47, the bacterial wilt caused by Ralstonia solanacearum18; and the bacterial spike blight caused by Rathayibacter tritici13. Likewise, the use of Streptomyces spp. has been reported against diseases caused by Xanthomonas phytopathogenic species. Streptomyces spp., isolated from rhizospheric soils of Artemisia tridentata, exhibited broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against phytopathogenic fungi, oomycetes, and bacteria such as Rhizoctonia solani, Pythium ultimum, and X. campestris pv. campestris13. Bioactive metabolites produced by Streptomyces sp. J46 showed leaf suppression of the bacterial spot caused by X. arboricola pv. pruni25. Soil isolate S. hawaiiensis SE4 reduces the severity of the rice bacterial blight caused by X. oryzae pv. oryzae16. Streptomyces spp. with antibacterial activity could be an alternative to control the bacterial spot caused by Xanthomonas spp. in chili pepper and tomato10,38,51. The application of the Actinovate® AG product, which contains Streptomyces lydicus WYEC108 as the active ingredient, was effective in controlling the bacterial spot on squash caused by X. cucurbitae49.

Moreover, physical or chemical pretreatments of rhizospheric soil are among the strategies used for the isolation of actinobacteria to promote the growth of species that are otherwise uncultivable using conventional methods. Regarding microwave radiation, Wang et al.53 reported that microwave irradiation of soil samples increased the number of cultivable actinobacteria compared to non-irradiated samples. Furthermore, the authors noted that certain actinobacteria of the genus Streptomyces were cultivable only after microwave irradiation53.

Considering the above background, soil Streptomyces are a promising strategy for bacterial disease management in agricultural crops. Therefore, the present study aimed to isolate and identify Streptomyces-like actinobacteria from rhizospheric soil using physical pretreatments and to evaluate their antimicrobial activity against Xanthomonas sp.

Materials and methodsSoil samples and pretreatmentsActinobacteria were isolated from a soil sample that belongs to the Centro de Investigación y Asistencia en Tecnología y Diseño del Estado de Jalisco (CIATEJ) Soil Collection of the Phytopathology Laboratory. The soil sample was maintained in storage at room temperature for three years and three months. The rhizospheric soil sample was collected from a bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) plantation in the locality of Bañuelos, Zacatecas (23°22′50.7″N; 103°00′44.7″W) in 2014 (Fig. 1). A portion of 100g of soil was sieved using a fine 8-mesh steel strainer (2.38mm). The sieved soil was prepared using two physical methods: dry heat and microwave radiation. The dry heat pretreatment was performed heating 10g of soil at 70°C for 1h in a drying oven11. The pretreatment with microwave radiation was conducted in accordance with that described by Wang et al.53 with slight modifications. In a sterile 15-ml test tube, 10g of soil were deposited and moistened with 4ml of distilled sterile water. The test tube was placed within a 1l precipitation glass beaker with 900ml of water and then irradiated with microwaves at a power of 100% (1100W) for 3min using a microwave oven (2450MHz, Microwave Mod. NN-989B, Panasonic Inverter System Inside). The prepared soil samples were set to cool down for 30min at room temperature and then mixed with 90ml of sterile distilled water for 5min.

Isolation of actinobacteriaActinobacteria were isolated following the sowing by extension technique, using potato-dextrose agar and adding 2g/l of yeast extract (PDA-Y; pH 7.0), 12.5mg/l of nalidixic acid and 50mg/l of cycloheximide, as described by Trinidad-Cruz et al.51. Soil suspensions were diluted in sterile distilled water until 1/1000 dilution. A 100μl aliquot of 1/100 up to 1/1000 dilutions was scattered in Petri (90mm in diameter) PDA-Y plates and incubated at 28°C for 7–14 days. The colonies with similar colony characteristics in morphology to Streptomyces19 bacteria were streaked on the PDA-Y plates until pure cultures were obtained. The isolates were preserved by transferring spores and/or mycelia into cryotubes containing 25% (v/v) glycerol at −80°C44. Pure isolates were named using the “BV” code, indicating Biotecnogía Vegetal in Spanish (translated as Plant Biotechnology); “BZ” indicating the sampling site Bañuelos, Zacatecas; and “MW” indicating those isolates obtained in the pretreatment using microwaves.

Phytopathogenic bacteriaXanthomonas sp. BV801 (laboratory strain)26,36 was cultured in nutrient-yeast extract glycerol agar [NYGA; 5g/l of Bacto™ Peptone (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA), 3g/l of yeast extract, 20g/l of glycerol and 15g/l agar]5 at 28°C for two days. For Xanthomonas sp. BV801 antimicrobial activity essays, 20ml of NYG broth (NYGB), was cultured at 28°C at 200 RPM for 18h; a bacterial suspension was prepared at an OD600nm of 1 with fresh NYGB using a spectrophotometer.

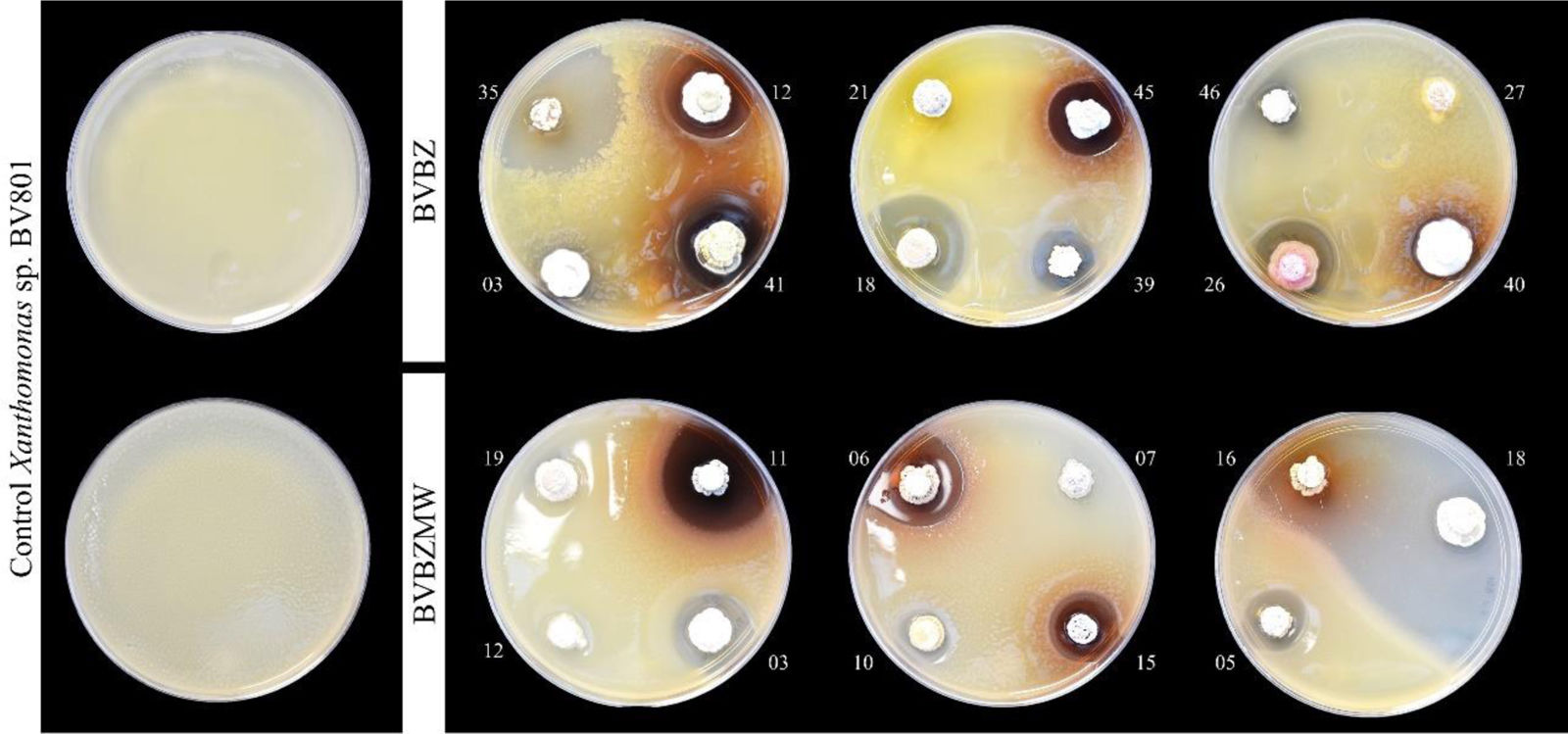

Antimicrobial activity assayThe antibacterial activity of the isolates against Xanthomonas sp. BV801 was determined by the double agar assay, as described by Dopazo et al.7 with slight modifications51. Previously, the isolates were cultured on PDA-Y plates at 28°C for seven days. Agar-mycelium 7.5-mm disks in diameter were prepared for each isolate and inoculated using the point of application method45 on PDA plates. The agar-mycelium disks were placed at 1cm of distance from the plate border in x shape and incubated at 28°C for five days. After incubation, the overlay agar was poured onto the PDA plates, which was prepared mixing 400μl of Xanthomonas sp. BV801 suspension with 4ml of soft NYGA (6g/l agar) tempered at 48°C. As control, the overlay agar mixture was poured onto the PDA plates without actinobacteria. The plates were incubated at 28°C for two days. The inhibition halo was measured from the center of the agar disc of each actinobacterium to the periphery of the surrounding growth of Xanthomonas sp. BV801. In cases where the growth of Xanthomonas sp. BV801 did not fully surround the agar disc due to inhibitory effects; therefore, the radius of the inhibition halo – from the center of the disc to the edge of Xanthomonas sp. growth – was measured. In both cases, results were expressed as the diameter of the inhibition halo. The diameter or radius of the inhibition zone caused by Xanthomonas sp. BV801 was measured using a digital Vernier caliper.

Experimental design and statistical analysisThe experiments were performed using a completely randomized experimental design. For each isolate and control, three replicates were used. Data of the inhibition halos were analyzed using ANOVA (analysis of variance) and Tukey's (p≤0.05) multiple comparisons of means, using StatGraphics Centurion XVI (version 16.2.04, StatPoint Technologies, Inc. USA) statistical package.

DNA extractionThe BVBZ 35, BVBZ 47, and BVBZMW 18 isolates were cultured in 25ml of potato-dextrose broth adding up 2g/l of yeast extract (pH 7.0) at 28°C with orbital agitation at 200 RPM for five days. The bacterial cultures were centrifuged at 13000 RPM for 10min. Each isolate biomass was frozen at −80°C for 6h, lyophilized and ground in a mixing grinder at 25Hz for 5min (MM 400, Retsch®, Haan, Germany). DNA was extracted from 1-mg biomass using the Dynabeads® DNA DIRECT™ Universal (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) kit as recommended by the producer and stored at −20°C until subsequent use.

Molecular identification of the actinobacterial strainsThe identification of the BVBZ 35, BVBZ 47, and BVBZMW 18 isolates was performed by amplifying the 16S rRNA gene for the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using oligonucleotides fD1 (5′-CCGAATTCGTCGACAACAGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and rD1 (5′-CCCGGGATCCAAGCTTAAGGAGGTGATCCAGCC-3′)54. The PCR was performed in a total volume of 50μl that contained buffer PCR 1×, 1.5mM de MgCl2, 0.16mM of each dNTP, 12pmol of each oligonucleotide, 1.25 Taq DNA polymerase units (High Fidelity PCR Enzyme Mix, Fermentas, Waltham, MA, USA) and 4μl of the DNA extraction. PCR was performed in a thermocycler under the following conditions: one initial denaturalization at 94°C for 3min; followed by 35 amplification cycles at 94°C for 30s, 58°C for 30s and 72°C for 1.5min, and one final extension at 72°C for 10min. The amplification products were subjected to electrophoresis in agarose gel at 1.2% stained with GelRed® (Biotium, Inc., Fremont, CA, USA) at 90V for 1h and visualized under ultraviolet fluorescence. The amplified fragments were purified using the Wizard® PCR Preps DNA Purification Resin (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) kit as recommended by the producer and sequenced by Sanger in Macrogen Inc. (Seoul, KR), using the oligonucleotides 800R (5′-TACCAGGGTATCTAATCC-3′), 1100R (5′-GGGTTGCGCTCGTTG-3′) and rD1.

The sequences obtained from each isolate were assembled, analyzed, and cut using SnapGene® (ver. 4.3.7, GSL Biotech, Chicago, IL, USA). The 16S rRNA consensus sequences of each isolate were compared with the material type sequences available in the GenBank database using the BLASTn (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) program of the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) website. The sequences of the closest species to the isolates were discharged from the GenBank database41; the similarity of the 16S rRNA gene sequence values were calculated using the Pairwise Nucleotide Sequence Alignment For Taxonomy tool available in the EzBioCloud (https://www.ezbiocloud.net/tools/pairAlign) website. The isolate sequences and those that recorded similar values greater than 99% were aligned in a multiple form using the MUSCLE (predetermined parameters) algorithm. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method40 based on the Kimura-2 parameters nucleotide substitution model22, and the branch trust value was determined by the bootstrap analysis, with 1000 resamplings12. All the analyses were performed in MEGA1148 software. The 16S rRNA gene sequences of Streptomonospora salina YIM 90002T (AF178988) and Streptosporangium roseum DSM 43021T (CP001814) were used as an external group. The 16S rRNA gene of the BVBZ 35, BVBZ 47, and BVBZMW 18 isolates were deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers MT756003, OQ569350, and OQ569351, respectively.

ResultsPhysical pretreatment effects on isolated actinobacteriaOf the 73 isolates obtained, 50 (68%) were recovered (BVBZ 01 to BVBZ 50 series) from the pretreated soil sample with dry heat and 23 (32%) were isolated from the microwave-irradiated samples (BVBZMW 01 to BVBZMW 23 series).

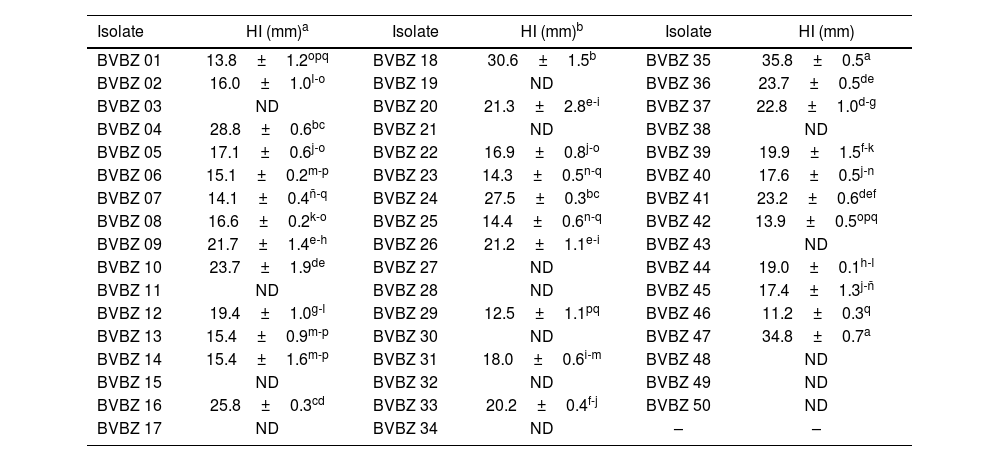

Antimicrobial activity of the isolatesOf the BVBZ series, 34 (68%) isolates showed antimicrobial activity against Xanthomonas sp. BV801 observed as inhibition halos in the confrontation assays (11.2–35.8mm in diameter) (Table 1 and Fig. 2). The BVBZ series isolates caused significant (p≤0.05) differences in Xanthomonas sp. BV801 inhibition halos (Table 1), of which those of BVBZ 35 and BVBZ 47 recorded the greatest inhibition halos with 35.8±0.5 and 34.8±0.7mm in diameter, respectively.

Inhibition halos (HI) of actinobacteria of the BVBZ series recorded during the antimicrobial assay activity against Xanthomonas sp. BV801.

| Isolate | HI (mm)a | Isolate | HI (mm)b | Isolate | HI (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BVBZ 01 | 13.8±1.2opq | BVBZ 18 | 30.6±1.5b | BVBZ 35 | 35.8±0.5a |

| BVBZ 02 | 16.0±1.0l-o | BVBZ 19 | ND | BVBZ 36 | 23.7±0.5de |

| BVBZ 03 | ND | BVBZ 20 | 21.3±2.8e-i | BVBZ 37 | 22.8±1.0d-g |

| BVBZ 04 | 28.8±0.6bc | BVBZ 21 | ND | BVBZ 38 | ND |

| BVBZ 05 | 17.1±0.6j-o | BVBZ 22 | 16.9±0.8j-o | BVBZ 39 | 19.9±1.5f-k |

| BVBZ 06 | 15.1±0.2m-p | BVBZ 23 | 14.3±0.5n-q | BVBZ 40 | 17.6±0.5j-n |

| BVBZ 07 | 14.1±0.4ñ-q | BVBZ 24 | 27.5±0.3bc | BVBZ 41 | 23.2±0.6def |

| BVBZ 08 | 16.6±0.2k-o | BVBZ 25 | 14.4±0.6n-q | BVBZ 42 | 13.9±0.5opq |

| BVBZ 09 | 21.7±1.4e-h | BVBZ 26 | 21.2±1.1e-i | BVBZ 43 | ND |

| BVBZ 10 | 23.7±1.9de | BVBZ 27 | ND | BVBZ 44 | 19.0±0.1h-l |

| BVBZ 11 | ND | BVBZ 28 | ND | BVBZ 45 | 17.4±1.3j-ñ |

| BVBZ 12 | 19.4±1.0g-l | BVBZ 29 | 12.5±1.1pq | BVBZ 46 | 11.2±0.3q |

| BVBZ 13 | 15.4±0.9m-p | BVBZ 30 | ND | BVBZ 47 | 34.8±0.7a |

| BVBZ 14 | 15.4±1.6m-p | BVBZ 31 | 18.0±0.6i-m | BVBZ 48 | ND |

| BVBZ 15 | ND | BVBZ 32 | ND | BVBZ 49 | ND |

| BVBZ 16 | 25.8±0.3cd | BVBZ 33 | 20.2±0.4f-j | BVBZ 50 | ND |

| BVBZ 17 | ND | BVBZ 34 | ND | – | – |

ND: non-detectable.

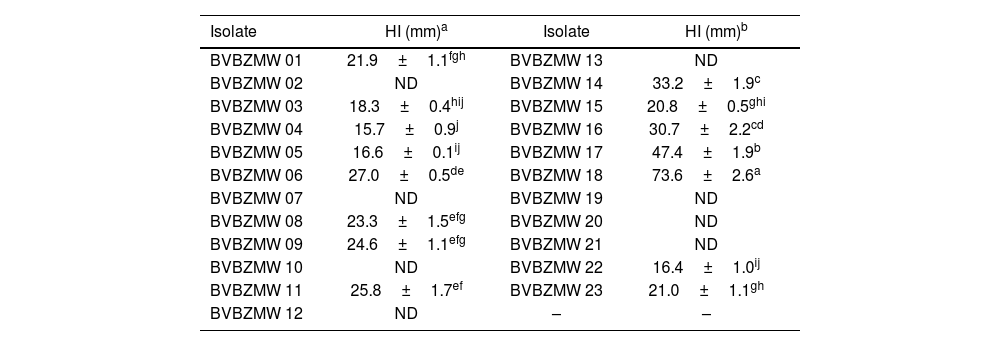

On the other hand, of the BVBZMW series, 15 (65%) of 23 inhibited Xanthomonas sp. BV801 growth with halos from 15.7 to 73.6mm in diameter (Table 2 and Fig. 2). The greatest significant differences in Xanthomonas sp. BV801 inhibition (p≤0.05) were recorded for isolate BVBZMW 18 (73.6±2.6mm), followed by BVBZMW 17 (47.4±1.9mm) and BVBZMW 14 (33.2±1.9mm) isolates.

Inhibition halos (HI) of actinobacteria of the BVBZMW series recorded during the antimicrobial assay against Xanthomonas sp. BV801.

| Isolate | HI (mm)a | Isolate | HI (mm)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| BVBZMW 01 | 21.9±1.1fgh | BVBZMW 13 | ND |

| BVBZMW 02 | ND | BVBZMW 14 | 33.2±1.9c |

| BVBZMW 03 | 18.3±0.4hij | BVBZMW 15 | 20.8±0.5ghi |

| BVBZMW 04 | 15.7±0.9j | BVBZMW 16 | 30.7±2.2cd |

| BVBZMW 05 | 16.6±0.1ij | BVBZMW 17 | 47.4±1.9b |

| BVBZMW 06 | 27.0±0.5de | BVBZMW 18 | 73.6±2.6a |

| BVBZMW 07 | ND | BVBZMW 19 | ND |

| BVBZMW 08 | 23.3±1.5efg | BVBZMW 20 | ND |

| BVBZMW 09 | 24.6±1.1efg | BVBZMW 21 | ND |

| BVBZMW 10 | ND | BVBZMW 22 | 16.4±1.0ij |

| BVBZMW 11 | 25.8±1.7ef | BVBZMW 23 | 21.0±1.1gh |

| BVBZMW 12 | ND | – | – |

ND: non-detectable.

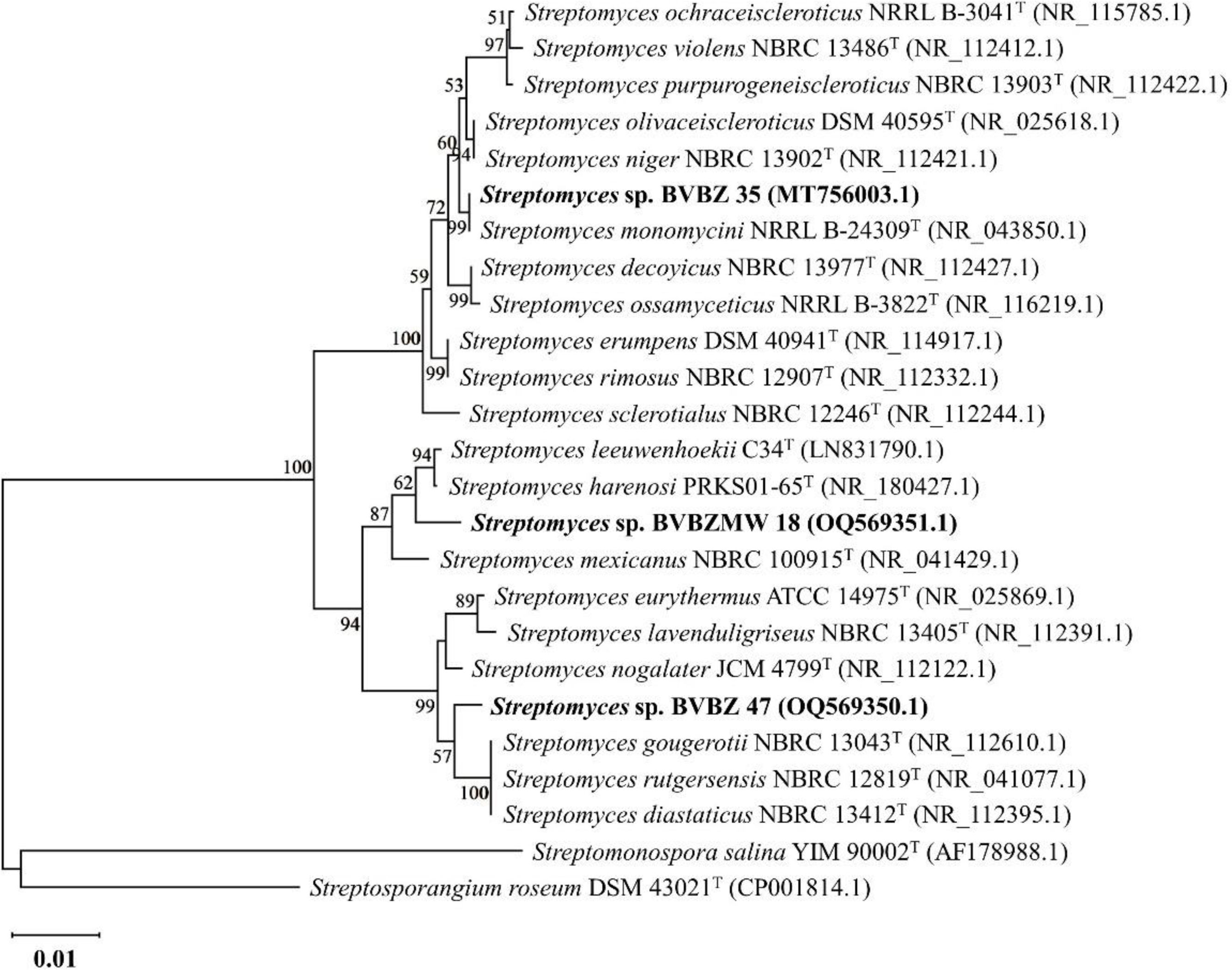

The results of the BLASTn program for the 16S rRNA gene sequences of isolates BVBZ 35 (1125bp), BVBZ 47 (1289bp), and BVBZMW 18 (1462bp) confirmed that they belong to genus Streptomyces. Isolate BVBZ 35 shared the greatest rRNA 16S gene sequence identity with S. monomycini NRRL B-24309T (100%), followed by S. olivaceiscleroticus DSM 40595T (99.73%) and S. niger NBRC 13902T (99.73%). For isolate BVBZ 47, the closest type of strain was S. nogalater JCM 4799T (99.38%) with rRNA 16S gene sequence similarity with S. eurythermus ATCC 14975T, S. lavenduligriseus NBRC 13405T, S. gougerotii NBRC 13043T, and S. rutgersensis NBRC 12819T, sharing a 99.07% similarity value. The comparative analysis of the 16S rRNA gene sequence showed that isolate BVBZMW 18 shared the greatest similarity values with S. leeuwenhoekii C34T (99.45%), S. harenosi PRKS01-65T (99.38%), and S. mexicanus NBRC 100915T (99.25%).

The phylogenetic analysis based on the 16S rRNA gene sequence indicated that isolates BVBZ 35, BVBZ 47 and BVBZMW 18 were grouped with their closest Streptomyces genus neighbors (Fig. 3). Streptomyces sp. BVBZ 35 formed a well-supported clade with its closest relative, S. monomycini NRRL B-24309T, exhibiting 100% sequence identity and a high bootstrap value of 99%. Streptomyces sp. BVBZMW 18 formed a distinct branch within the phylogenetic tree and clustered with S. leeuwenhoekii C34T (99.45% similarity) and S. harenosi PRKS01-65T (99.38% similarity), with a bootstrap support value of 62%. Unlike the two previous isolates, the phylogenetic analysis indicated that the subclade formed by Streptomyces sp. BVBZ 47 was closely related to S. gougerotii NBRC 13043T (99.07%), S. rutgersensis NBRC 12819T (99.07%), and S. diastaticus NBRC 13412T (99.06%) (Fig. 3).

Neighbor joining phylogenetic tree based on the 16S rRNA gene sequence showing the phylogenetic relationships among Streptomyces strains isolated from soil (BVBZ 35, BVBZ 47, and BVBZMW 18) and their closest relatives. The bootstrap values (>50%) are shown next to the branches. The 16S rRNA gene sequence of Streptomonospora salina YIM 90002T and Streptosporangium roseum DSM 43021T were used as external group. GeneBank accession numbers are shown in parentheses. Bar=0.01 substitutions per nucleotide position.

The soil from a bean plantation showed Streptomyces isolates with a weak to strong antibacterial activity against Xanthomonas sp. BV801. From Agave cupreata agricultural soils, Rincón-Enríquez et al.37 found that 14 Streptomyces-type isolates inhibited the growth of P. syringae pv. phaseolicola 1448A by 50–100%. Encheva-Malinova et al.10 reported that Streptomyces spp., isolated from Antarctic soils, produced inhibition halos ranging from 11 to 40mm in diameter against Xanthomonas phytopathogenic strains. In a previous study, Streptomyces isolates obtained from avocado cv. Hass tree soil recorded similar inhibition halos (15.5–62.7mm in diameter) against Xanthomonas sp. BV80151. Other studies mentioned that S. lydicus 5US-PDA8 showed inhibition percentages from 9.2 to 70.8% against several Xanthomonas strains causing bacterial chili spot38, whereas S. lydicus WYEC 108 recorded an inhibition halo of 10.6mm in diameter against X. cucurbitae49. Soil isolate Streptomyces sp. J46 showed antibacterial activity against X. arboricola pv. pruni25. In the present study, the result of a significant antimicrobial activity against Xanthomonas sp. BV801 suggests that Streptomyces (BVBZ 35, BVBZ 47, and BVBZMW 18) are potential candidates for the biological control of these phytopathogens; nevertheless, in vivo studies are required to subsequently prove this activity.

On the one hand, actinobacteria, especially those of the genus Streptomyces, are a prominent bioactive secondary metabolite source with different biological activities29. In the present study, Streptomyces sp. BVBZ 35, closely related to S. monomycini NRRL B-24309T, showed antimicrobial activity (inhibition halo of 35.8mm in diameter) against Xanthomonas sp. BV801 phytopathogen bacteria. This activity could be due to the production of secondary metabolites. Similarly, Meidani et al.28 reported S. monomycini ATHUBA 220 antimicrobial activity against non-phytopathogenic bacteria and yeast, which showed the greatest activity against Lactobacillus fermentum ATCC 9338 and Saccharomyces cerevisiae DSM 70449. As reported by Sadegui et al.39, S. monomycini C 801 showed antimicrobial activity against the phytopathogenic oomycete Phytophthora drechsleri. Recently, a S. monomycini RVE129 purified bioactive compound, known as setomycin, recorded antibacterial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria9. In other studies, antibacterial secondary metabolite production has been reported by S. monomycini NRRL B-24309T as monomycine19, argolaphos A and B17. Subsequent studies are necessary to determine which metabolites of Streptomyces sp. BVBZ 35 strain may be implied in Xanthomonas sp. BV801 in vitro growth inhibition.

On the other hand, Streptomyces sp. BVBZ 47 shared the greatest similarity with S. nogalater JCM 4799T (99.38%); however, the phylogenetic analysis indicated that it was closely related to S. gougerotii NBRC 13043T, S. rutgersensis NBRC 12819T, and S. diastaticus NBRC 13412T. Recently, Komaki and Tamura23 reported that a polyphasic taxonomic study reclassified S. gougerotii NBRC 13043T and S. rutgersensis NBRC 12819T as subsequent heterotypical synonyms of S. diastaticus NBRC 13412T. Based on these findings, the closest Streptomyces sp. BVBZ 47 relative was S. diastaticus NBRC 13412T. The production of bioactive compounds for S. diastaticus has been reported in several studies, with compounds such as rimocidin, CE-108, oligomycin A and B showing antimicrobial activity against fungi, yeast, and P. capsici33,55. Rutamycin (also known as oligomycin D), isolated from S. rutgersensis NBRC 12819T, showed antifungal but not antibacterial activity43. The production of antimicrobial secondary metabolites of other closer relatives of Streptomyces sp. BVBZ 47 have been reported previously. S. nogalater JCM 4799T produces nogalamycin50, a powerful antibiotic against Gram-positive bacteria4.

From one S. lavenduligriseus strain, Filipin III was purified and identified in three new polyene macrolides, which exhibited from strong to weak antifungal activity against Candida albicans56. The antimicrobial activity of the closest Streptomyces sp. BVBZ 47 relatives, agrees with that observed in the present study in which the isolated strain showed strong antimicrobial activity (inhibition zone of 34.8mm in diameter) against Xanthomonas sp. BV801 Gram-negative bacteria.

The phylogenetic analysis placed Streptomyces sp. BVBZMW 18 in a clade with S. leeuwenhoekii C34T and S. harenosi PRKS01-65T, S. leeuwenhoekii C34T, originally isolated from the Atacama Desert, is known to produce the antibiotics chaxamycins A–D, chaxalactins A–C, and hygromycin A34,35 antibiotics. Among the chaxamycins, chaxamycin D showed a strong antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and several strains of Staphylococcus aureus34 whereas chaxalactines A-C recorded a strong antibacterial activity against Gram-positive (St. aureus ATCC 25923, Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 19115 and Bacillus subtilis NCTC 2116) bacteria but weak activity against Gram-negative (E. coli ATCC 25922 and Vibrio parahemolyticus NCTC 10441) bacteria35. Kusuma et al.24 indicated that the genome of S. harenosi PRKS01-65T, a bacterium isolated from a sand dune, contains several biosynthetic genes with the potential to produce new natural products.

Streptomyces type strains, closely related to the Streptomyces strains identified in this study, have been shown to be a source of secondary metabolites with antimicrobial activity. However, Kiepas et al.21 reported that, due to the complex taxonomy of the Streptomyces genus, 16S rRNA gene sequences, as a single molecular marker, are not suitable for species-level assignment. The authors suggest that other approaches, such as multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) or core genome MLSA (cgMLSA) are needed, as they are more accurate for taxonomic assignment.

In our study, 16S rRNA gene sequencing enabled assignment of the selected isolates to the genus Streptomyces, and phylogenetic analysis indicated that their closest relatives are secondary metabolite producers with antimicrobial activity. However, further studies are needed to assign the Streptomyces spp. from this study to the species level (either as a previously described species or as a new taxon). Furthermore, it is key to identify the possible secondary metabolites involved in the antimicrobial activity of Streptomyces spp.

The results of the present study demonstrated that the pretreatment of the soil samples by the physical methods were effective for obtaining Streptomyces isolates with antibacterial activity against Xanthomonas sp. BV801. Particularly Streptomyces sp. BVBZMW 18 could only be cultured after irradiating the soil sample with microwaves, which was confirmed by the molecular identification of isolates with significant antimicrobial activity. Likewise, Wang et al.53 observed that some antagonist antibacterial strains belonging to the genera Streptomyces, Streptosporangium, and Lentzea were only culturable from microwave-irradiated soil samples.

In another study, Niyomvong et al.30 indicated that the majority of the rare actinobacteria from the genera Microbispora, Micromonospora, Nocardia, and Nonomuraea were isolated from microwave-irradiated soil samples compared to non-irradiated ones. Recently, Arango et al.2 and Hamedi et al.14 reported that the greatest number of actinobacterial type isolates were obtained from the microwave pretreatment. In the present study, the opposite effect was observed, where the pretreatment with microwaves recorded fewer than half of the Streptomyces (23) type isolates, compared with the pretreatment using dry heat (50). Although the pretreatment with microwaves has been used in several studies as a tool for isolating actinobacteria, to our knowledge, it is still unknown how the irradiation of the microwaved samples affects the culturable actinobacteria53.

The Streptomyces type isolates obtained from the bean rhizospheric soil showed antimicrobial activity against Xanthomonas sp. BV801, which caused the chili pepper bacterial spot. Among them, Streptomyces sp. BVBZ 35, BVBZ 47, and BVBZMW 18 showed a significant antimicrobial activity. The electromagnetic radiation pretreatment was an effective tool for obtaining Streptomyces type isolates with antimicrobial activity. This could be observed in the Streptomyces sp. BVBZMW 18 strain, which stood out for its inhibitory activity. Streptomyces sp. BVBZ 35, BVBZ 47, and BVBZMW 18 are potential candidates for the biological control of the causal agent of bacterial spot in chili pepper crops. Likewise, other unidentified isolates from the microwave-irradiated soil, such as BVBZMW 14, BVBZMW 16 and BVBZMW 17, could be considered in subsequent studies for their antimicrobial activity, similar to that of Streptomyces obtained from soil pretreated with dry heat.

FundingThis research was funded by CIATEJ Phytopathology Laboratory internal projects.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare having no conflict of interest.

J.R. Trinidad-Cruz is grateful to Conahcyt (Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencias y Tecnologías) for the scholarship granted for Doctoral (CVU 424465), D. Fischer for translation and edition.