Diseases that involve the medium caliber airways (segmental and subsegmental bronchi) are common and present clinically with nonspecific respiratory symptoms such as cough, recurrent respiratory infections and occasionally, hemoptysis. The abnormal and irreversible dilation of bronchi is known as “bronchiectasis”. The diagnosis can be challenging and the analysis of the regional distribution of the bronchiectasis is the most useful diagnostic guide. The objective of this manuscript is to describe the main imaging findings of bronchiectasis and their classification, review the diseases that most commonly present with this abnormality, and provide an approach to the diagnosis based on their imaging appearance and anatomic distribution. Bronchiectasis is a frequent finding that may result from a broad range of disorders. Imaging plays a paramount role in diagnosis, both in the detection and classification, and in the diagnosis of the underlying pathology.

La patología de las vías respiratorias de medio calibre (bronquios segmentarios y subsegmentarios) es común y se presenta con síntomas respiratorios poco específicos, como tos, infecciones de repetición y en ocasiones hemoptisis. La dilatación permanente del árbol bronquial se conoce como «bronquiectasia» y representa un reto diagnóstico. El análisis de la distribución regional de las bronquiectasias en los diferentes lóbulos pulmonares es la guía diagnóstica más útil. El objetivo de este trabajo es describir los hallazgos de imagen de las bronquiectasias y sus diferentes tipos, revisar las situaciones más comunes y proponer un algoritmo diagnóstico basado en su distribución anatómica. Las bronquiectasias son un hallazgo frecuente, resultado de un amplio espectro de enfermedades. Los estudios de imagen desempeñan un papel esencial en su detección, clasificación y orientación diagnóstica hacia la patología subyacente.

Bronchiectases are a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways that involve dilation and progressive destruction of the brochial wall. Due to the little specificity of their clinical manifestations, such as chronic cough, recurrent respiratory infections, expectoration or hemoptysis, the imaging modalities play an important role in its diagnostic guide and treatment.

Chest X-ray is the initial study in patients presenting with respiratory symptoms.1 Recognizing the findings that characterize bronchiectases is esencial in their diagnostic algorythm. The computed tomography (CT) scan is the imaging modality of choice in the study of the airways,2–4 and specifically in the diagnosis of bronchiectases thanks to the anatomic information it provides, both of the airway and the lung parenchyma, and its high spatial resolution so needed if we want to visualize small bronchial structures. In addition, the CT scan can provide the keys to the etiological diagnosis of bronchiectases. CT protocols with low radiation doses allow its use in young patients and among the pediatric population.5–7

The goal of this work is to describe the imaging findings of bronchiectases as well as their different types, to review the most common diseases that present this abnormality and to propose a diagnostic algorithm based on its anatomical distribution.

Definition, classification and imaging findingsThe term “bronchiectasis” is reserved to describe permanent localized or diffused dilation of the bronchi.8–10 Bronchiectases usually occur due to chronic infectious processes; recurrent inflammation; obstruction of the bronchial lumen; or systemic diseases,9,11 resulting in a vicious circle of infection and inflammation that alters the dynamics of the airways and the mucociliary transport, weakening the wall, making it collapse and promoting the retention of secretions.12 In up to 50 per cent of the cases the cause is not identified.11

The abnormal dilation of the bronchioles is called bronchiolectasis8 and it is usually of inflammatory etiology, or secondary to pulmonary fibrosis.

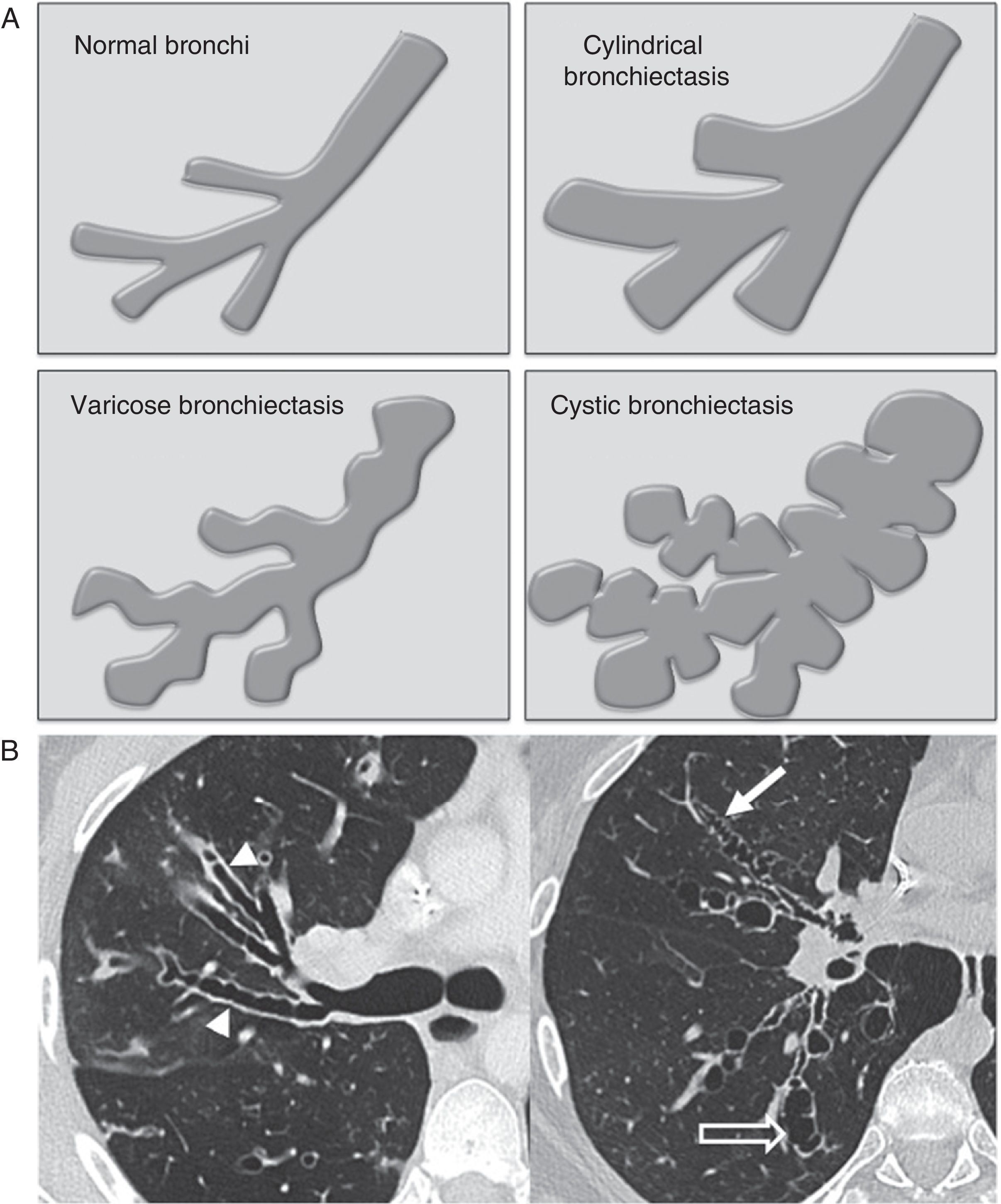

Based on their macroscopic morphology, bronchiectases are categorized into three main groups13–cylindrical, varicose and cystic. Although this categorization has an excellent correlation with the bronchiectases morphology seen in the CT scans, its use is of little diagnostic utility,14 since the different types usually coexist and they can be associated with more than just one disease:

- •

Cylindrical bronchiectasis consists of the uniform dilation of segmental brochi (Fig. 1A and B), in most cases spreading to subsegmental branches.

Figure 1.(A) Illustrations of the different morphological types of bronchiectases. (B) Axial CT scan slices in two patients illustrating the different morphological types of bronchiectases: cylindrical bronchiectasis (arrowheads), varicose bronchiectasis (white arrow) and cystic bronchiectasis (hollow arrow).

- •

Varicose bronchiectases are characterized by the tortuosity of the affected bronchi, which, in addition to being dilated, have some sort of difuse pseudosaccular appearance (Fig. 1A and B).

- •

In cystic bronchiectasis, the bronchius acquires a rounded morphology forming spaces of cystic appearance that converge with one another in severe cases (Fig. 1A and B) capable of simulating a “honeycombe” pattern.

“Traction bronchiectases” are a subtype of varicose bronchiectases that occur in pulmonary fibrosis.9

Any of these types of bronchiectases can be associated with the thickening of the brochial walls and with mucoid impaction.

Chest X-ray findings are based on the severity and type of bronchiectasis.

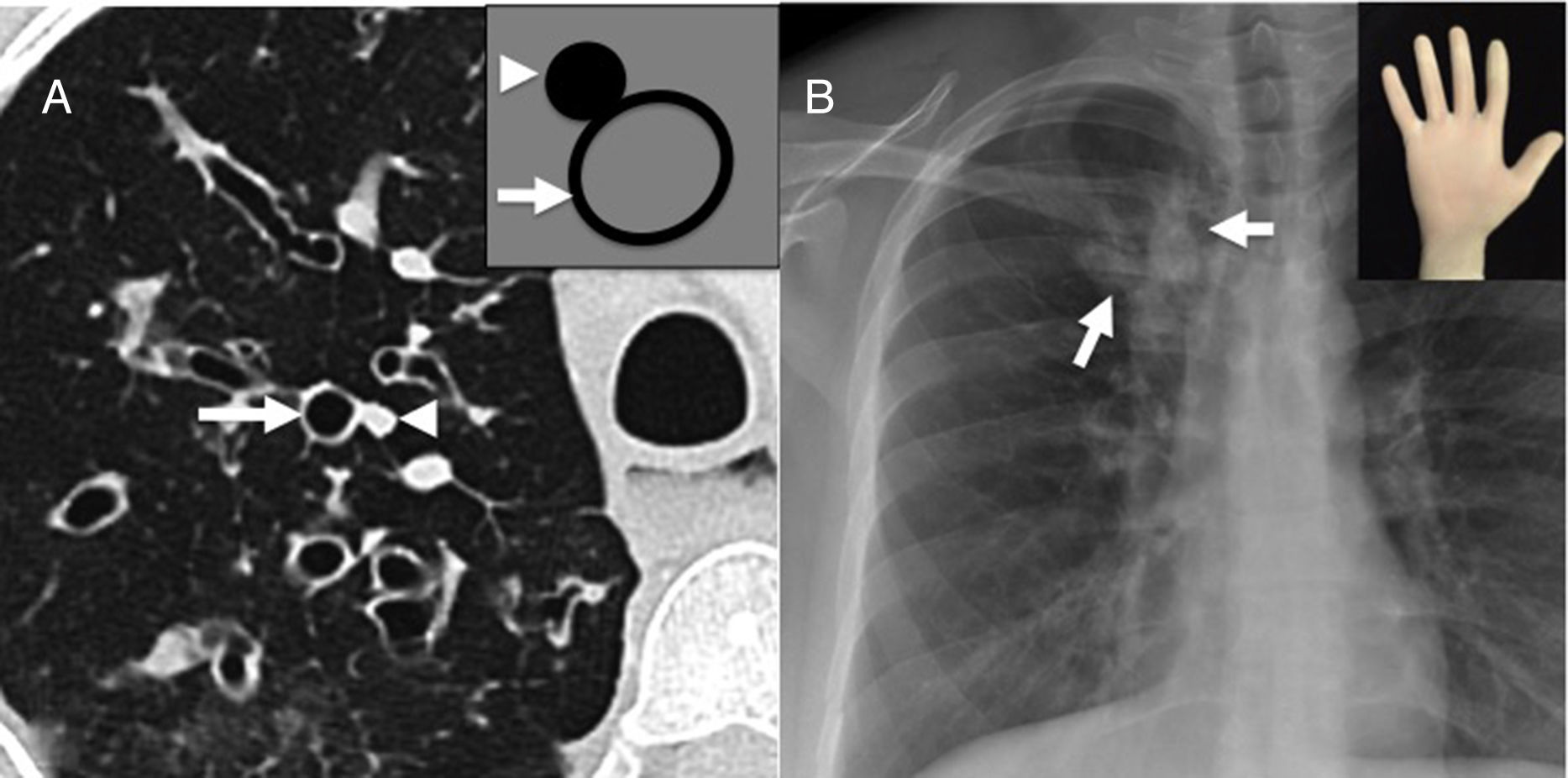

We should remember that: The “tram line” visualization of bronchial walls (Fig. 2), and the peripheral tubular opacities branching out, with the “finger-in-glove” sign in cases of severe proximal bronchial dilation (Fig. 3) are signs of bronchiectasis in the chest X-rays.9,15

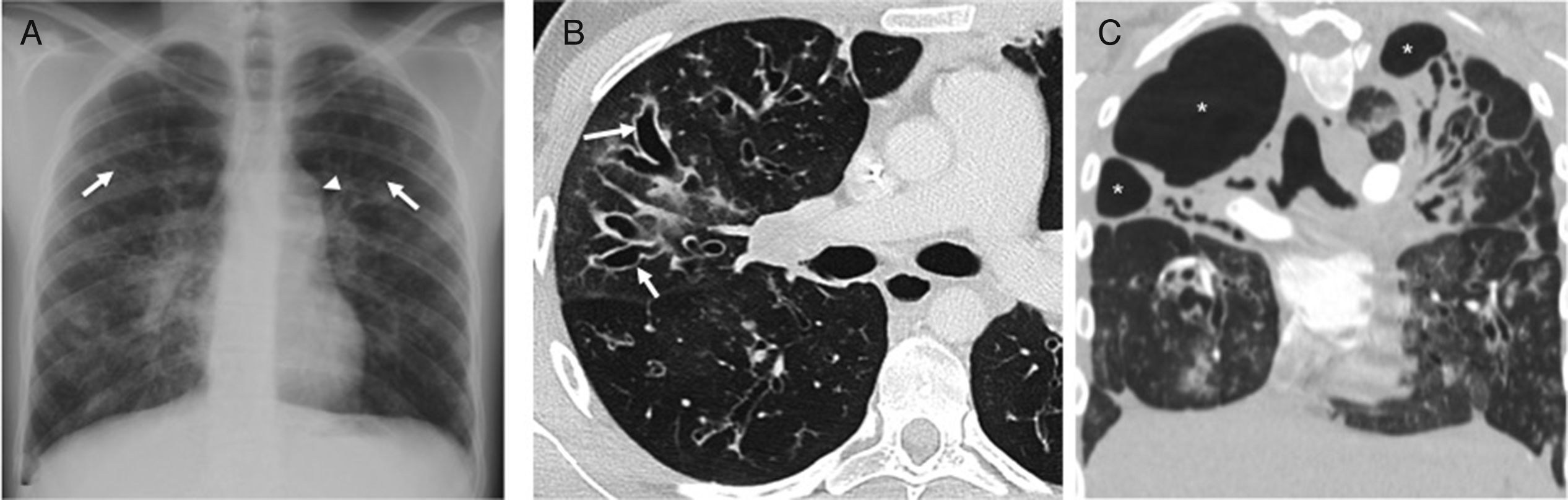

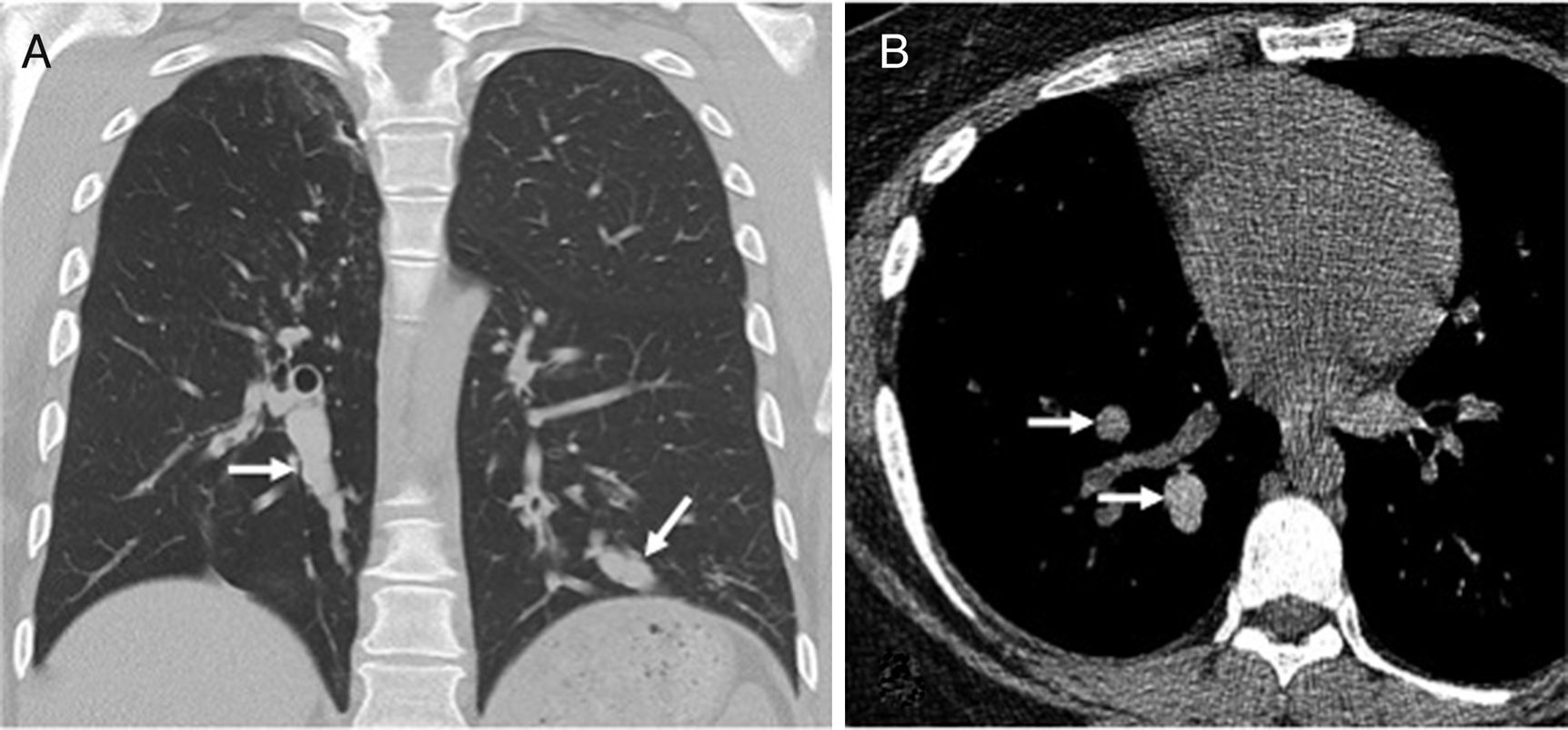

Twenty-three-year-old male with cystic fibrosis. (A) The chest X-ray shows extensive bronchial thickening, and “tramline” opacities predominantly in the superior lobes, secondary to bronchiectasis (arrows). The abnormal convexity of the aortopulmonary window (arrowhead) is due to associated mediastinal adenopathies. (B) Axial CT scan image confirming the existence of extensive cylindrical bronchiectases, mainly segmental and subsegmental (arrows). (C) Coronal CT reconstruction in another paciente with cystic fibrosis complicated with recurrent infections showing great distortion of lung architecture due to severe fibrosis and formation of bullae and apical cystic cavities (asterisks).

(A) Axial CT scan image showing “signet-ring sign” characterized by the abnormal proportion between arterial (arrowhead) and bronchial diameter (arrow) defining the presence of bronchiectasis. This sign takes its name because its appearance is similar to a ring and its stone (illustration). (B) Posteroanterior chest X-ray showing the “finger-in-glove” sign, characterized by one tubular opacity branching out (arrows) due to mucoid impaction and severe bronchial dilation.

In the CT scan axial images, the recognition of an abnormal caliber of the bronchi is based on the association between the arterial and bronchial calibers. Both the arteries and the bronchi travel while wrapped up by the same connective tissue (axial interstice) toward the pulmonary periphery, and when they branch out, the proportion between both their calibers remains relatively constant. We should not forget that the lack of progressive bronchial tapering toward the pulmonary periphery, and one bronchio-arterial relation >1 in the CT scan axial slices, are useful if we want to determine the presence of bronchiectases in adults.16 One dilated bronchus adjacent to its arterial branch with a smaller caliber gives the appearance of the characteristic “signet-ring sign”2,8,13 (Fig. 3).

In healthy people, bronchi are only visualized on the CT scan up to 2–3cm of the pleural surface. The only structure of the secondary pulmonary lobule that is normally seen is the centrilobular artery.8

We should remember that: visualization of the bronchi in the lung periphery is indicative of bronchiectasis.17

The thickening of bronchial walls; mucoid impactions; mosaic pattern; and air trapping are usually associated findings.

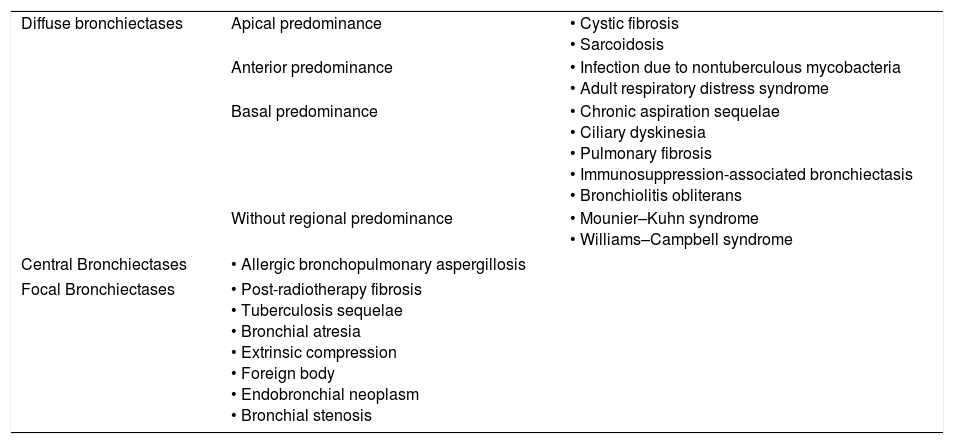

Etiologic diagnosis: the key is distributionThe analysis of the regional distribution of bronchiectasis is the most useful diagnostic guide (Table 1). They can be diffuse; central; or focal, and have a preference for apical, anterior or inferior pulmonary regions. Here is a look at them based on their regional distribution in order to facilitate the differential diagnosis.

Classification of bronchiectases based on their distribution.

| Diffuse bronchiectases | Apical predominance | • Cystic fibrosis • Sarcoidosis |

| Anterior predominance | • Infection due to nontuberculous mycobacteria • Adult respiratory distress syndrome | |

| Basal predominance | • Chronic aspiration sequelae • Ciliary dyskinesia • Pulmonary fibrosis • Immunosuppression-associated bronchiectasis • Bronchiolitis obliterans | |

| Without regional predominance | • Mounier–Kuhn syndrome • Williams–Campbell syndrome | |

| Central Bronchiectases | • Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis | |

| Focal Bronchiectases | • Post-radiotherapy fibrosis • Tuberculosis sequelae • Bronchial atresia • Extrinsic compression • Foreign body • Endobronchial neoplasm • Bronchial stenosis | |

The most common disease in this group is cystic fibrosis. It is a recesive autosomal genetic disorder due to an alteration of the gene that encodes the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein. It usually occurs in the pediatric age, with a wide spectrum of severity. Repeated respiratory infections and excessive production of sputum are the most common respiratory manifestations. Pancreatic failure and infertility are its most common systemic manifestations.5,18

Commonly, bronchiectases in cystic fibrosis are predominantly apical and peripheral, with damage of segmental and subsegmental bronchi in severe forms. Due to an abnormal mucociliary transport,5 there is an extensive mucoid impaction in the affected bronchi, which can dilate greatly and adopt cylindrical or cystic forms (Fig. 2A and B). Colonization by microorganisms such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa19 is not uncommon, which can result in extensive scarring (Fig. 2C).

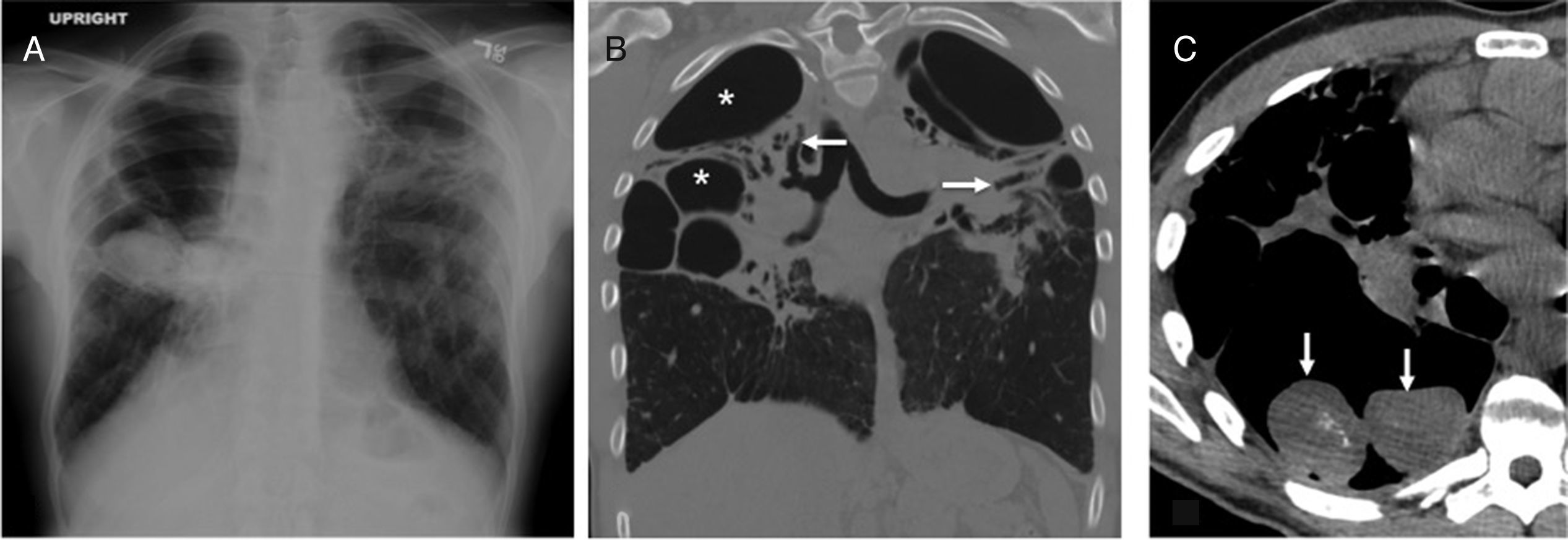

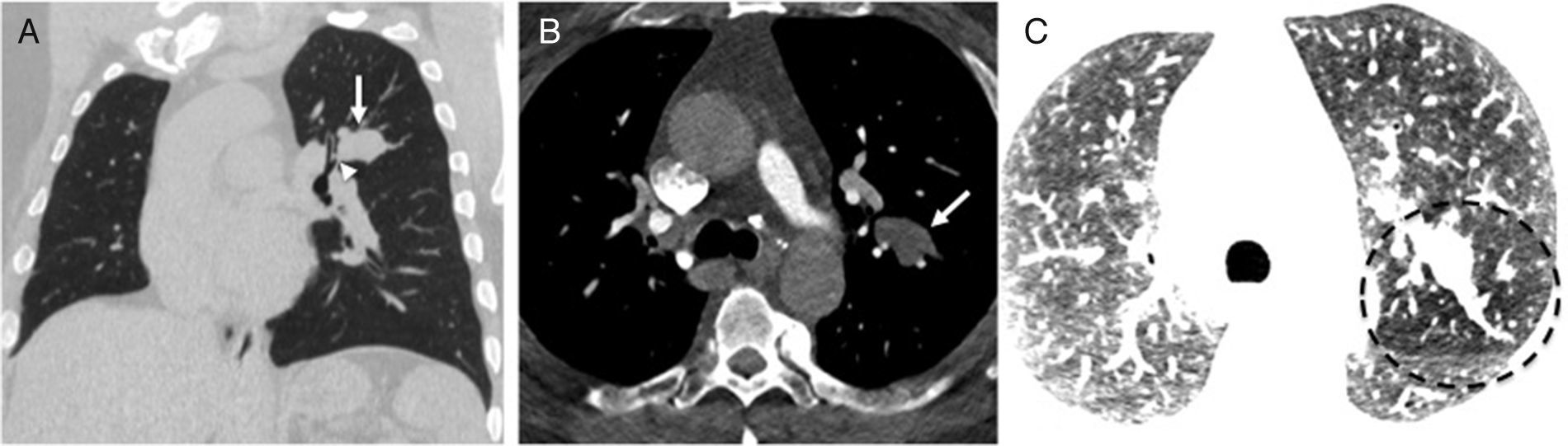

Bronchiectases in pulmonary sarcoidosis are seen in cases of severe interstitial fibrosis (stage 4) as traction bronchiectases15,20 that mainly affect the superior lobes (Fig. 4). Other associated findings characteristic of sarcoidosis are calcifications of hilar and mediastinal nodes, and perilymphatic nodes.20

Fifty-eight-year-old male with a history of pulmonary sarcoidosis. The posteroanterior chest X-ray (A) and the Coronal CT reconstruction (B) show the characteristic distortion of the pulmonary parenchyma secondary to advanced sarcoidosis. There is traction bronchiectasis (arrows) and apical cavities (asterisks) due to severe fibrotic changes. The axial CT scan image (C) shows solid and partially calcified masses within the cavities representative of mycetomas (arrows) due to saprophytic colonization by Aspergillus.

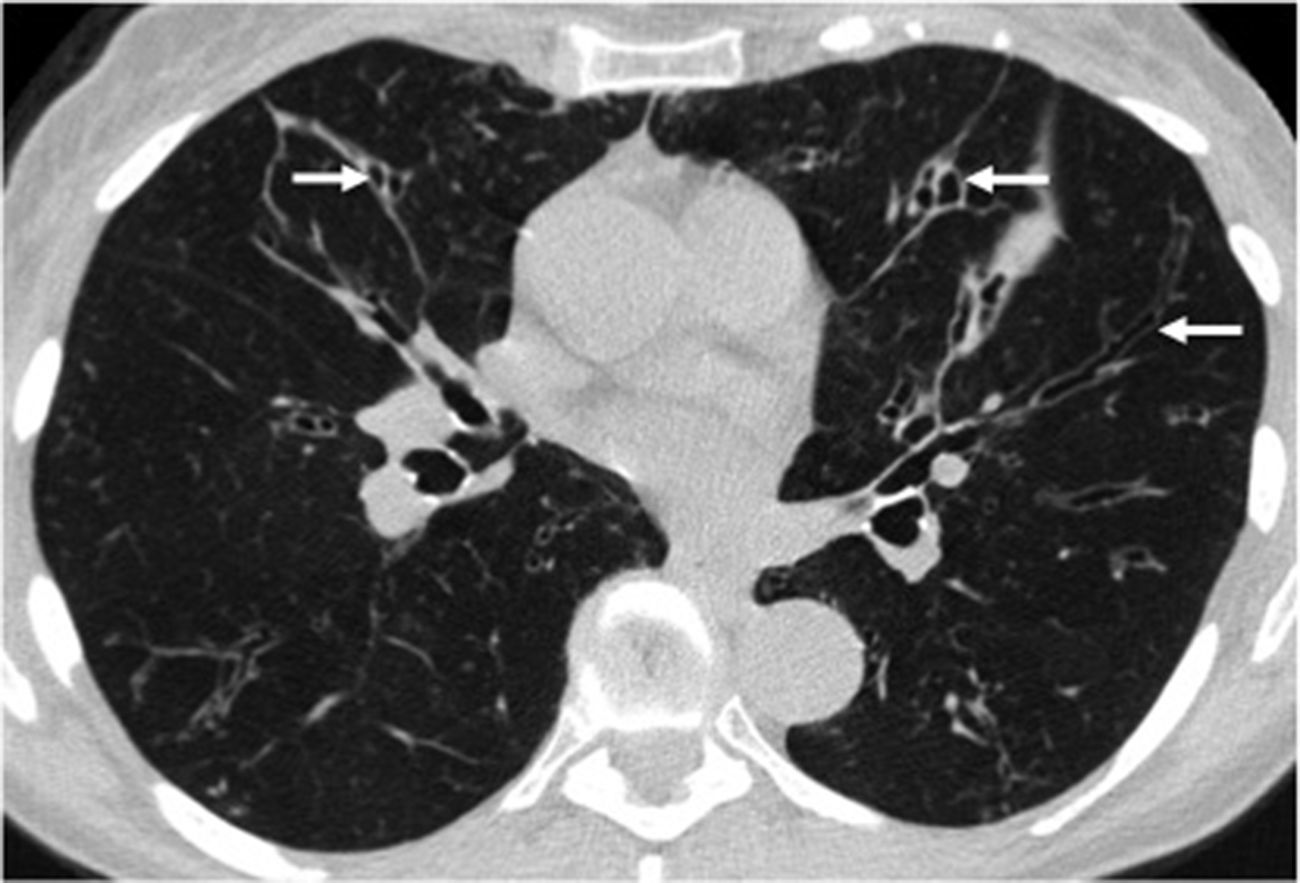

Infection due to non-tuberculous mycobacteria usually affects the middle lobe and the lingula in middle-aged women with normal immunity with recurrent cough.21,22 Bronchiectases are cylindrical and varicose, associated with bronchial thickening, mucus plugs and peribronchiovascular nodes (Fig. 5).

Fifty-eight-year-old woman with chronic cough of several years duration. The axial CT scan image shows diffuse bronchial thickening and segmental and subsegmental cylindrical bronchiectases in the middle lobe and the lingula (arrows). This distribution is characteristic of chronic infection due to nontuberculous mycobacteria.

In the adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), after its early inflammatory phase, the proliferation of fibroblasts results in pulmonary fibrosis.23 Both the predominantly anterior distribution of fibrosis and traction bronchiectases seem to be due to the protective effect against the barotrauma exerted by consolidations, and the dependent atelectasis that characterize the early stages of ARDS.24

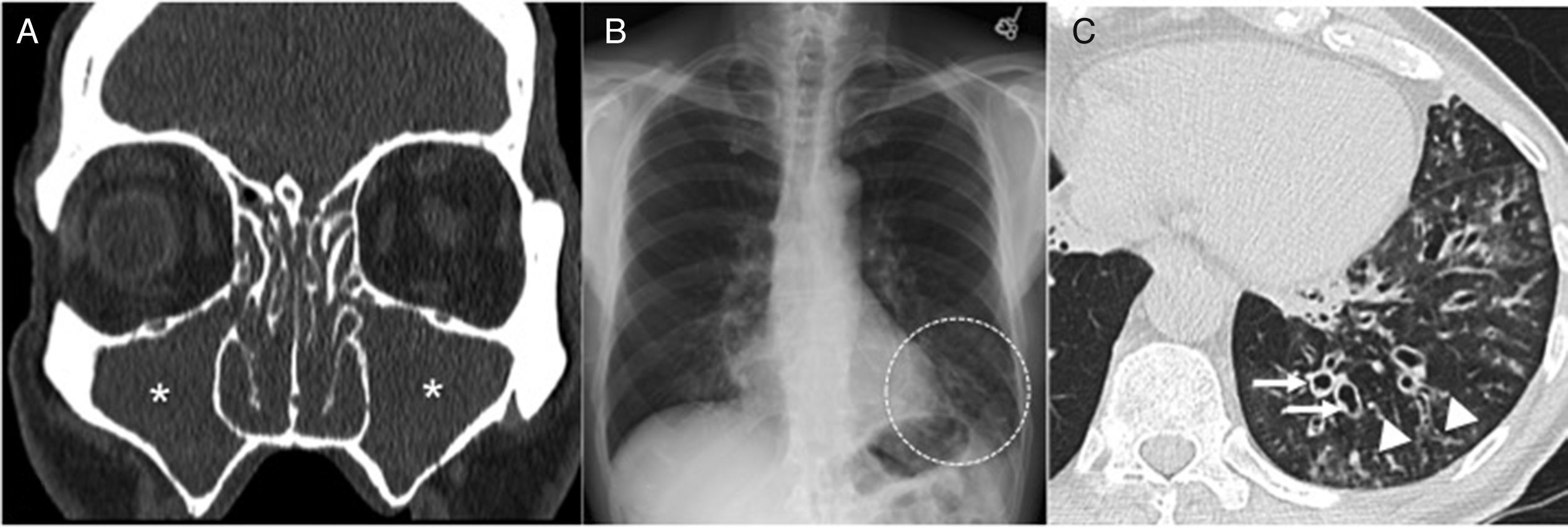

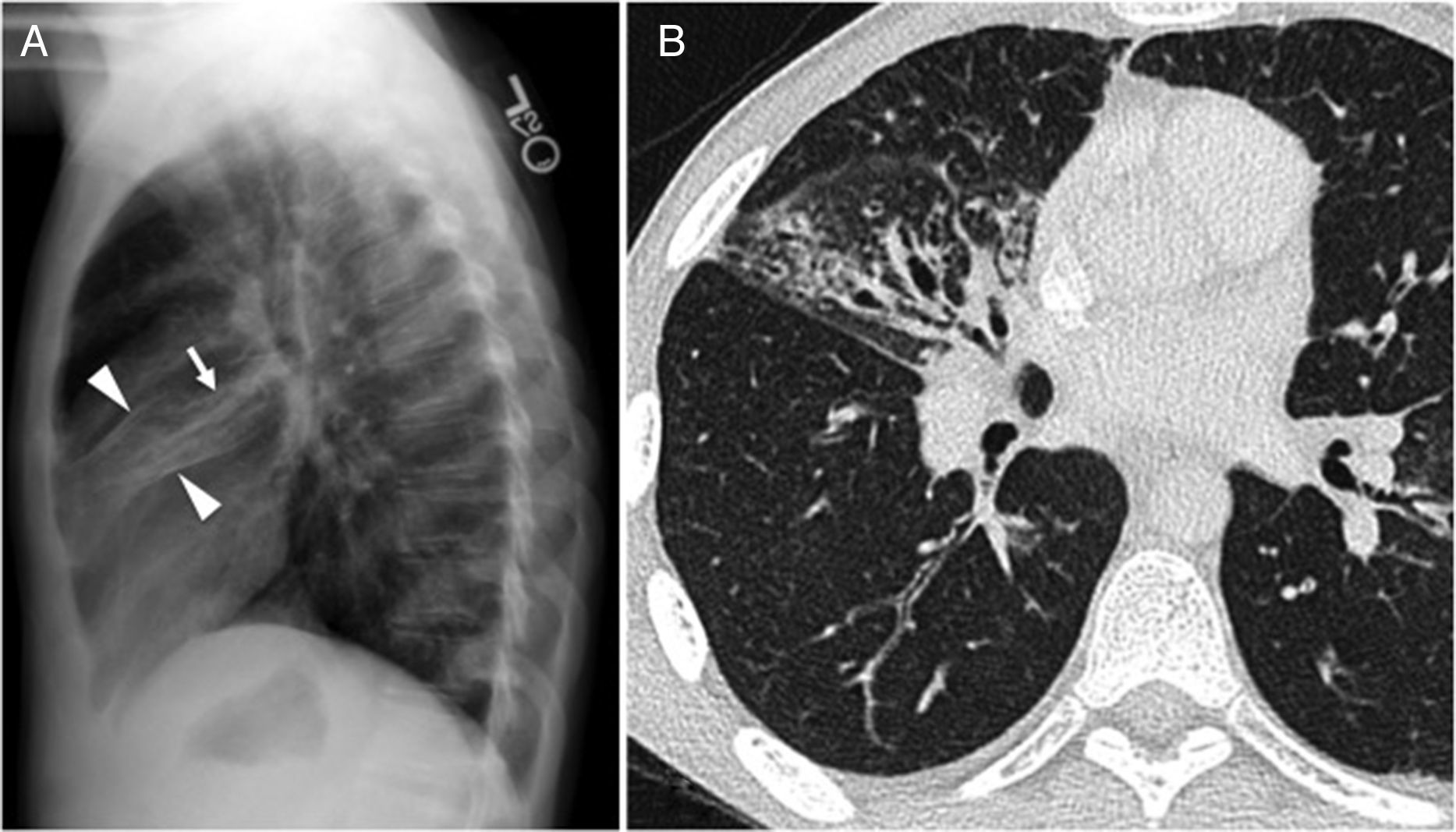

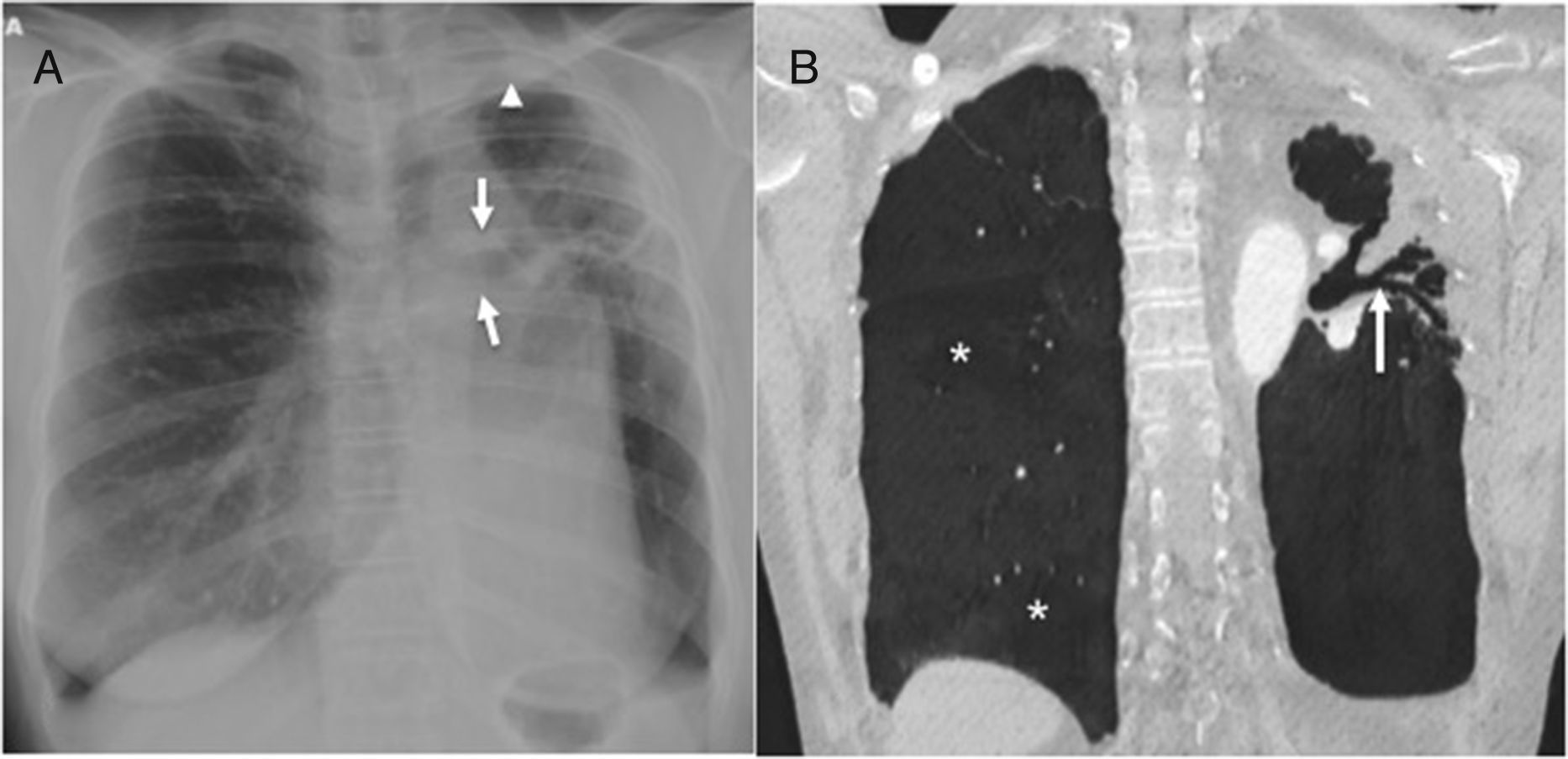

Diffuse bronchiectasis of basal predominant distributionThe ciliary dyskinesia syndrome is characterized by an abnormal mucociliary transport and it characteristically occurs with recurrent respiratory infections. The age of occurrence is variable, and patients can remain asymptomatic until adulthood.21,25 Due to a generalized ciliary dysfunction, it is invariably associated with sinusitis and often with alterations in sperm motility and male infertility. The Kartagener syndrome, characterized by situs inversus, bronchiectases and sinusitis, occurs in approximately half the patients with ciliary dyskinesia. The findings of bronchiectasis both on the chest X-rays and the CT scans are similar to the ones reported in other diseases that occur with bronchiectases, yet damage is predominantly basal26 (Fig. 6).

Forty-three-year-old male with a history of sinusitis, recurrent pneumonias and infertility. (A) The coronal CT scan image of paranasal sinuses shows extensive occupation of the maxillary sinuses (asterisks) and the ethmoidal air cells due to mucoid material. The bony walls of paranasal sinuses are intact. (B) The posteroanterior chest X-ray shows heterogeneous opacities in both pulmonary bases, predominantly in the left one. There are tubular transparencies and bronchial thickening, indicative of bronchiectasis (circle). (C) The axial CT scan image confirms the presence of bronchial thickening and dilation (arrows) in the inferior left lobe, and bronchiolectasis (arrowheads) due to distal bronchiolar damage.

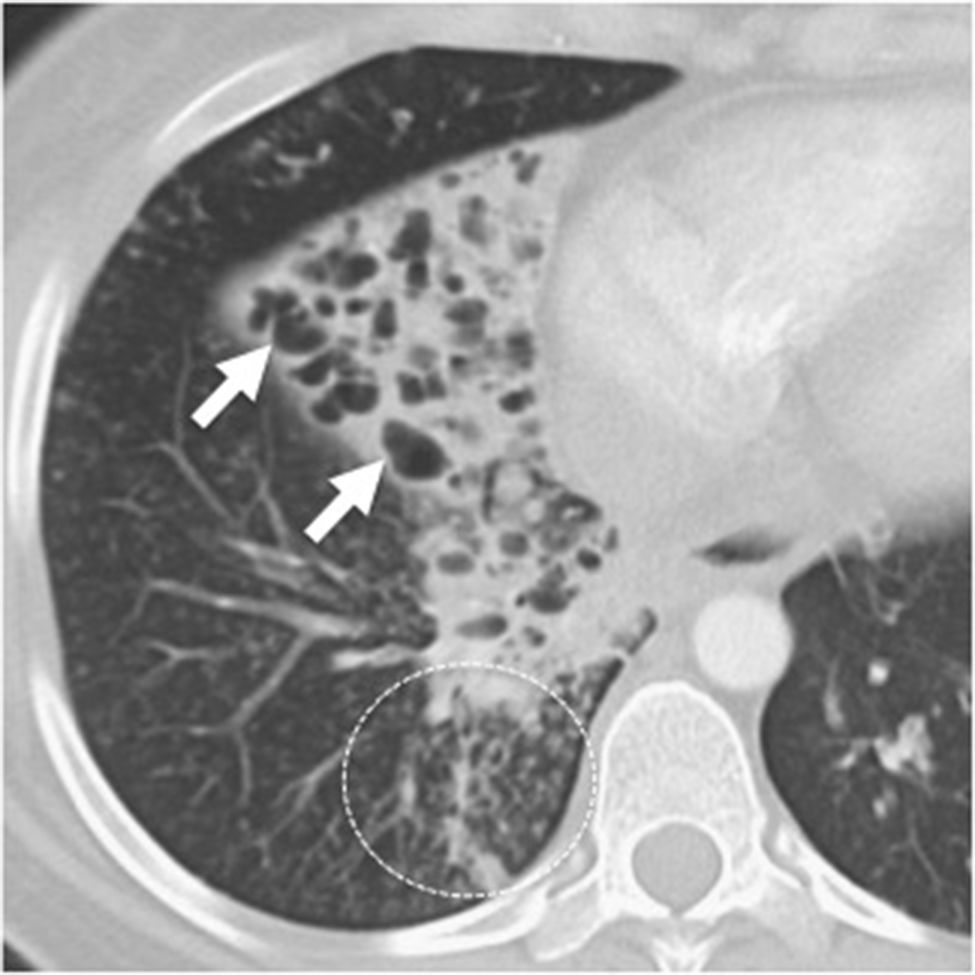

Aspiration bronchitis/bronchiolitis is a relatively misdiagnosed condition, but not an uncommon one. Patients with an altered mental status; dysfunction in their swallowing mechanism; or a history of neck neoplasms that may have required resection or radiotherapy are considered groups of risk. Due to the gravitational gradient, bronchiectases resulting from repeated microaspiration of gastric content are predominantly basal.27,28 In addition to bronchiectases, bronchial thickening, mucoid impaction, “tree-in-bud” opacities, and subsegmental atelectasis are common findings too (Fig. 7).

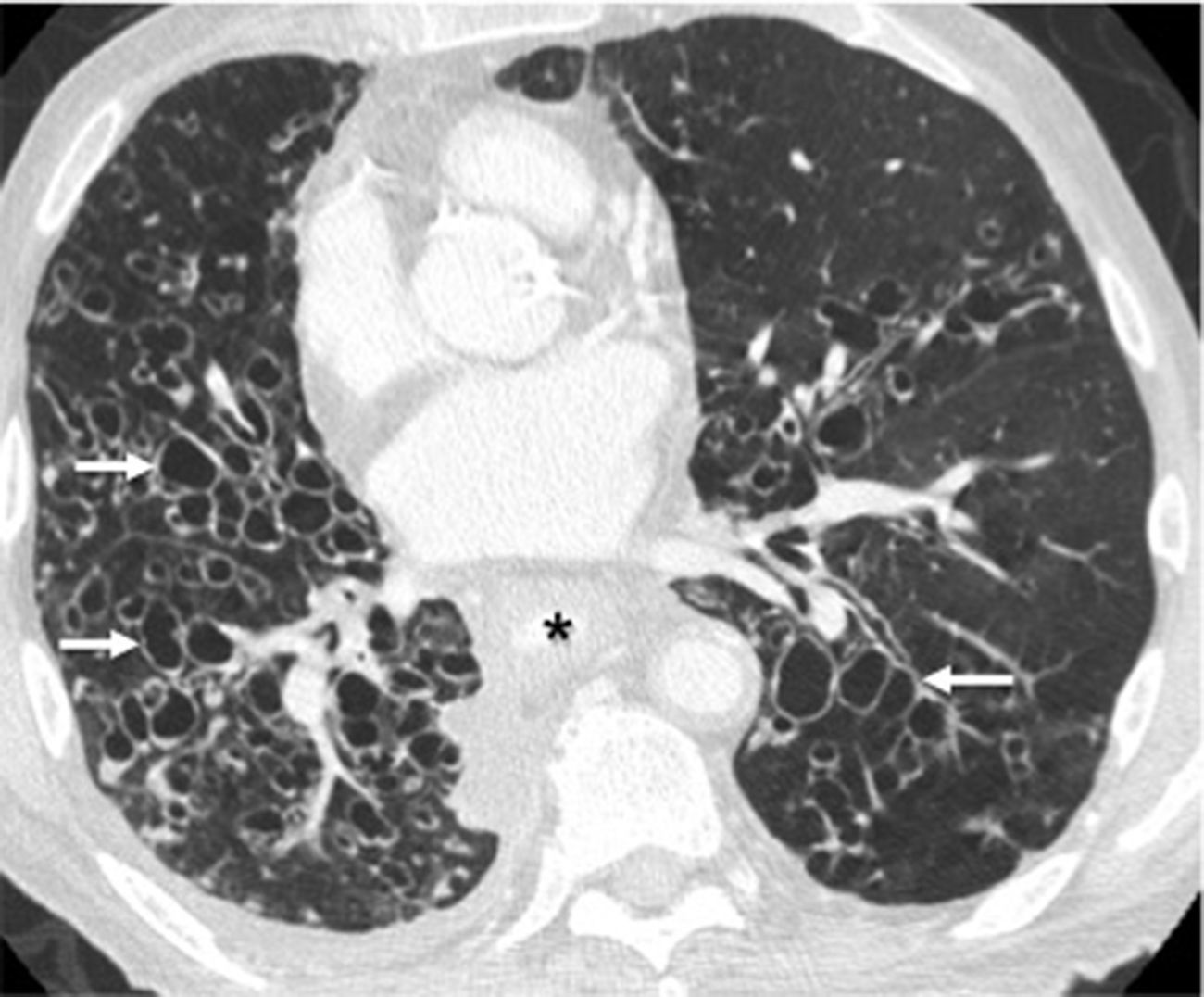

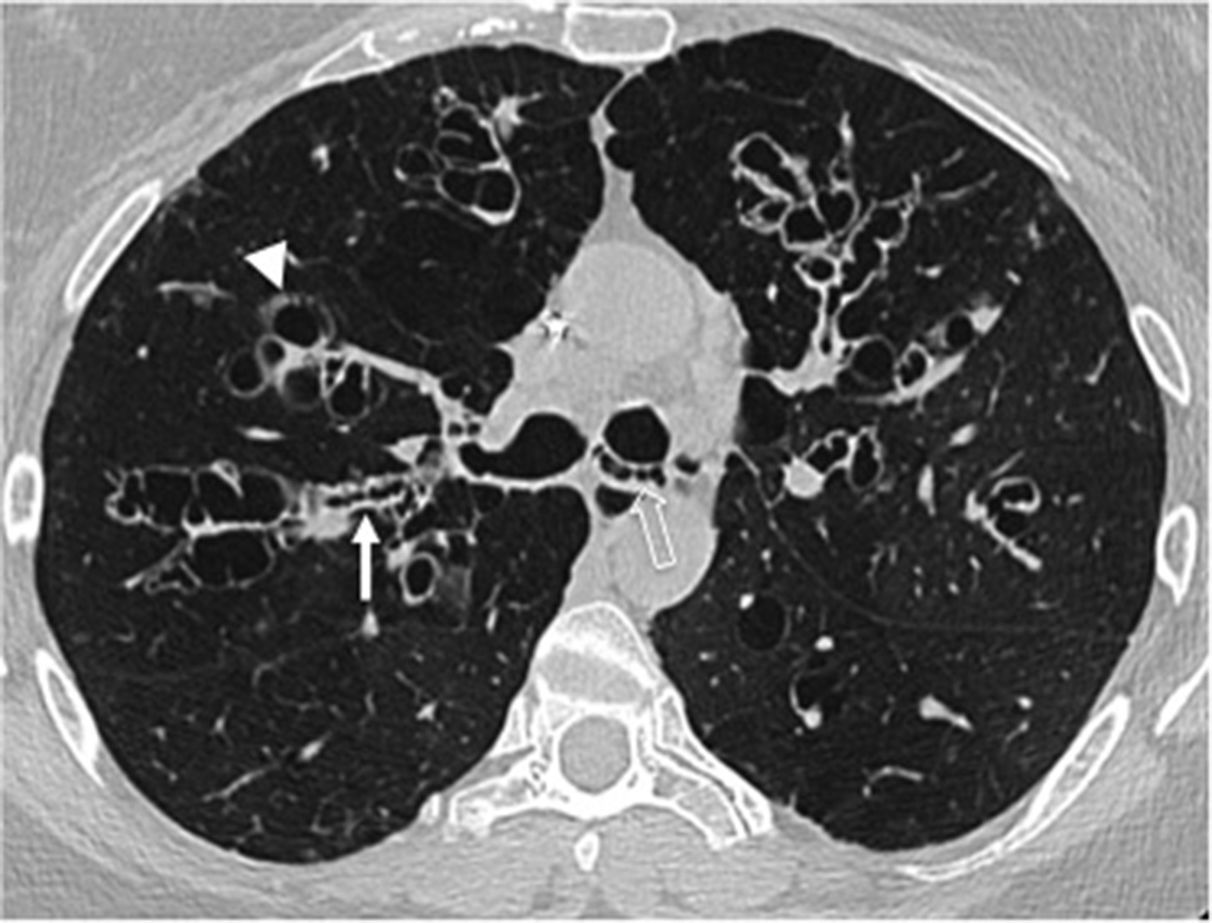

Bronchiectases associated with pulmonary fibrosis in cases of usual interstitial pneumonia and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia are also predominantly basal and are characteristically traction bronchiectases29 in the areas of fibrosis (Fig. 8).

Sixty-three-year-old male with a history of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis confirmed through lung biopsy. The high-resolution axial CT scan image shows bronchiectasis and traction bronchiolectasis (arrows) of a varicose morphology and secondary to underlying advanced pulmonary fibrosis, in this case being a usual interstitial pneumonia characterized by extensive subpleural reticulation and areas of basal honeycombing (arrowheads).

Simliarly, basal predominance has been reported in idiopathic bronchiectases and bronchiectases associated with hypogammaglobulinemia and immunosuppression30 (Figs. 9 and 10).

Forty-eight-year-old male with a history of chronic cough and recurrent pneumonia. The axial CT scan image shows consolidation and cystic bronchiectases in the middle lobe (arrows). There is also thickening of bronchial walls, centrilobular micronodes and “tree-in-bud” opacities (circle) in the lower right lobe due to multilobar condition.

Forty-seven-year-old male with a history of Crohn's disease with chronic cough. (A) Lateral chest X-ray showing bronchial thickening and partial volume loss in the middle lobe (arrowheads). We can see tubular “tramline” opacities (arrow), indicative of bronchiectasis. (B) The axial CT scan image confirms the radiographic findings. There is diffuse thickening of bronchial walls, yet the presence of bronchiectasis is limited to the middle lobe.

In patients with lung transplants, the development of bronchiolitis obliterans (BO) as a chronic dysfunction of the graft is well known and it occurs in up to 50 per cent of the cases.31 It is an important cause of morbidity and mortality, and develops in approximately 12–18 months after the trasplant.31,32 BO can also occur in patients with heart transplants33; in cases of graft versus host disease after hematopoietic stem cell trasplants; in occupational diseases, associated with systemic causes such as rheumatoid arthritis, or be of idiopathic nature.34,35 Bronchiectases associated with BO are usually predominantly basal, cylindrical and symmetrical. At times, they are associated with thickening of bronchial walls and mosaic attenuation of the pulmonary parenchyma. The latter finding, due to areas of regional air trapping, can be seen through the CT scan expiratory images, although it is not always observed and its presence is not related to the severity of the disease.31,32

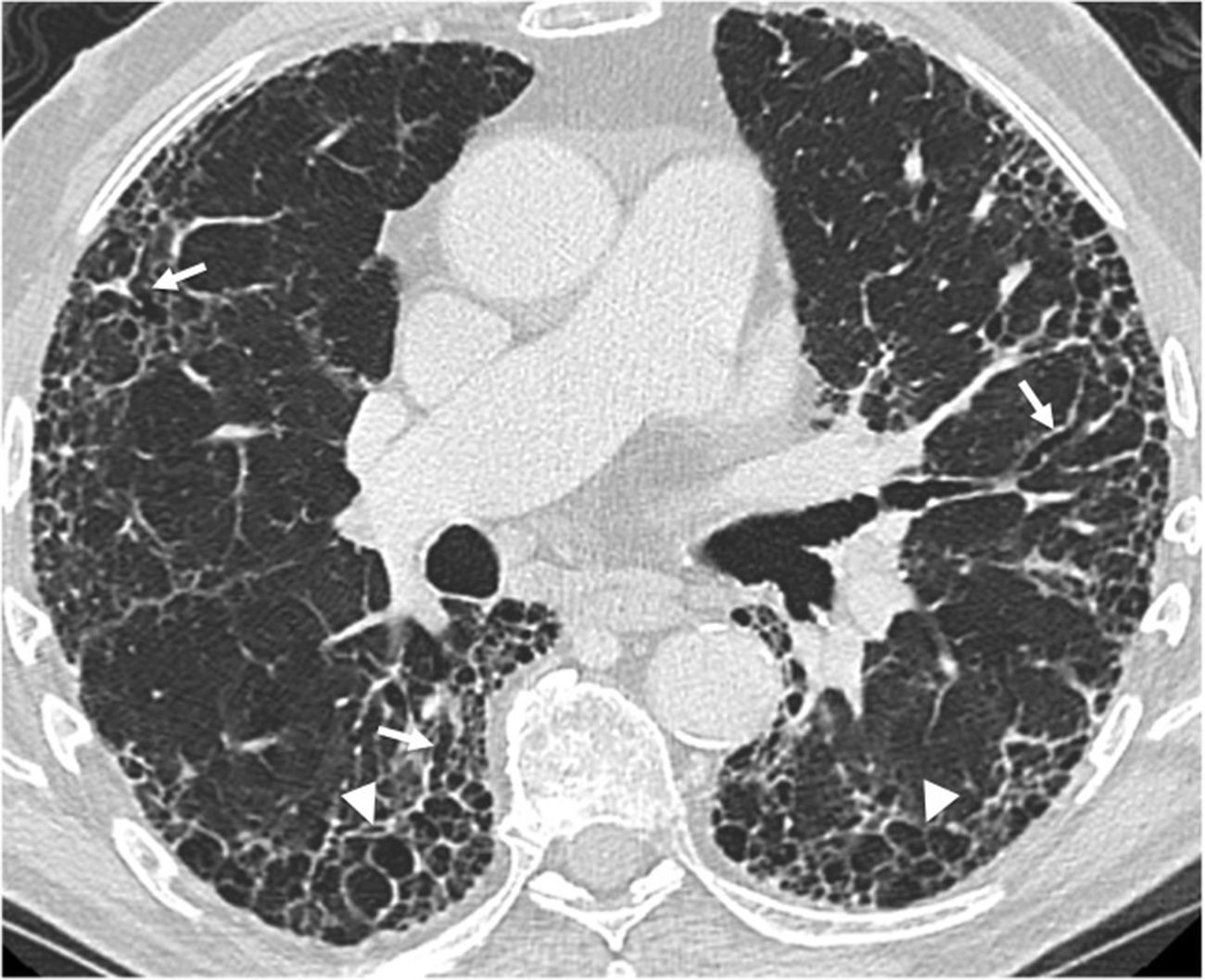

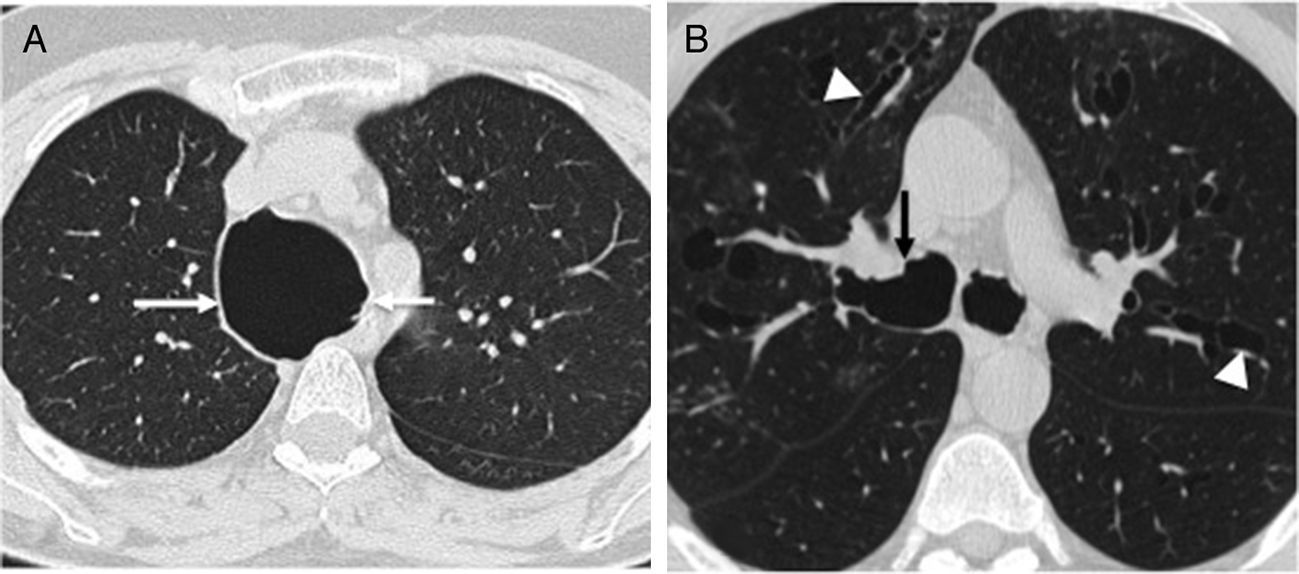

Diffuse bronchiectases without regional predominanceLess common diseases presenting wiht abnormalities in the airway cartilage composition, such as the Mounier–Kuhn syndrome, and the Williams–Campbell syndrome present with diffuse bronchiectases without regional predominance. The Mounier–Kuhn syndrome, also known as tracheobronchomegaly, is characterized by the caliber widening of the upper airways, with a tracheal diameter >3cm and main bronchi >2.4cm on the CT scans.2,36 Also, the presence of pseudodiverticuli on the tracheobronquial walls is characteristic of this condition (Fig. 11). The Williams–Campbell syndrome characteristically affects fourth to sixth generation bronchi, keeping the central airways untouched15 (Fig. 12).

Forty-nine-year-old woman with a history of chronic cough and recurrent respiratory infections. Axial CT scan image showing diffuse thickening of bronchial walls, and varicoid (white arrow) and cystic bronchiectasis (arrowhead) affecting the segmental and subsegmental bronchi. There are central bronchial pseudosacculations (hollow arrow), but the main bronchi and the tracheal caliber are normal. This set of findings is characteristic of the Williams–Campbell syndrome.

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis is characterized by large central bronchial dilations, with extensive mucus plugs and thick secretions, causing the classical “finger-in-glove” sign in the chest X-rays (Fig. 3). On the CT scan, the bronchial content shows a characteristically high attenuation17,37 (Fig. 13).

Forty-three-year-old woman with a history of asthma complicated with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. (A) Coronal CT reconstruction showing bronchiectasis and mucoid impactions with “glove-in-finger” appearance in both inferior lobes (arrows). (B) The axial image in a mediastinal window setting shows high density (54HU, arrows) in the lumen of bronchiectasis – a characteristic finding of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis.

Unlike the causes of diffuse bronchiectases, the presence of focal bronchiectases is usually secondary to the obstruction of the bronchial lumen (due to tumor, inflammation, foreign body, or stenosis), with the subsequent distal dilation of the bronchus.

We should remember that: the study of focal bronchiectases requires bronchoscopic assessment in order to determine and treat the cause.9 The “finger-in-glove” radiological sign, characterized by tubular opacity that may branch out, describes the appearance of focal bronchiectases occurring in cases of bronchial atresia, postinfectious bronchial stenosis, or secondary to a foreign body in a lobar or segmental bronchus. This type of bronchiectasis is also known as “bronchocele”,8 since these disorders result in the retention of secretion and the significant dilation of the affected bronchus (Fig. 14).

Thirty-one-year-old asymptomatic male. Coronal reconstruction (A) and axial CT scan slice (B) showing focal bronchiectasis with mucoid impaction in a characteristic “finger-in-glove” image in the upper left lobe (arrows), distal to bronchial atresia (arrowhead). (C) Axial image with contrast manipulation in the lung window in order to highlight segmental hypodensity secondary to trapping distal to the obstruction of the atrophied bronchus (encircled area).

Some inflammatory or infectious processes may cause focal bronchiectases, as it is the case with radiotherapy fibrosis. Traction bronchiectases appear close to the irradiated area as a result of pulmonary fibrosis.9 Also, the scarring process of infections such as tuberculosis in any of its stages, and specifically bronchial tuberculosis, is associated with bronchial wall damage and fibrosis, and results in bronchiectases.38 Since the bacillus tha causes tuberculosis has a preference for pulmonary apices, this type of post-tuberculous bronchiectases has a focal apical distribution (Fig. 15).

Twenty-five-year-old male with a history of tuberculosis treated during childhood; currently asymptomatic. (A) The posteroanterior chest X-ray shows cicatricial atelectasis with loss of upper left lobe volume and pulmonary hilum upper retraction (arrows). There is associated pleural apical thickening (arrowhead). (B) Coronal CT reconstruction in minimum intensity projection (MinIP) showing cylindrical bronchiectases (arrow) associated with total volume loss of the superior left lobe. There is compensatory expansion of right lung that shows areas of lesser attenuation (asterisks), indicative of air trapping, probably due to post-infectious bronchiolitis.

Bronchiectases are a common finding and they can be the result of a broad range of diseases, including congenital; infectious; inflammatory; systemic; and iatrogenic conditions. Imaging modalities play a crucial role in their detection and classification. Specifically, the analysis of its distribution through CT scans allows diagnostic guidance of the underlying disease.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments with human beings or animals have been performed while conducting this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors confirm that in this article there are no data from patients.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors confirm that in this article there are no data from patients.

Authors contribution- 1.

Manager of the integrity of the study: JB and LF.

- 2.

Study Idea: JB and LF.

- 3.

Study Design: JB and LF.

- 4.

Data Mining: JB and LF.

- 5.

Data Analysis and Interpretation: JB and LF.

- 6.

Statistical Analysis: N/A.

- 7.

Reference: JB and LF.

- 8.

Writing: JB and LF.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant remarks: JB and LF.

- 10.

Approval of final version: JB and LF.

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Bueno J, Flors L. Papel de los estudios de imagen en el diagnóstico etiológico de las bronquiectasias: la distribución es la clave. Radiología. 2018:60;39–48.