The analysis of the causes that have given rise to a change in tendency in the incidence and mortality rates of breast cancer in the last few decades generates important revelations regarding the role of breast screening, the regular application of adjuvant therapies and the change of risk factors. The benefits of early detection have been accompanied by certain adverse effects, even in terms of an excessive number of prophylactic mastectomies. Recently, several updates have been published on the recommendations in breast cancer screening at an international level. On the other hand, the advances in genomics have made it possible to establish a new molecular classification of breast cancer. Our aim is to present an updated overview of the epidemiological situation of breast cancer, as well as some relevant issues from the point of view of diagnosis, such as molecular classification and different strategies for both population-based and opportunistic screening.

El análisis de las causas que han provocado un cambio de tendencia en la incidencia y la mortalidad del cáncer de mama en las últimas décadas genera revelaciones importantes sobre el papel del cribado mamográfico, el empleo regular de terapias adyuvantes y la alteración de los factores de riesgo. Los beneficios de la detección precoz se han acompañado de ciertos efectos adversos, incluso en forma de un excesivo número de mastectomías profilácticas. Recientemente se han publicado diversas actualizaciones internacionales sobre las recomendaciones en cribado del cáncer de mama. Por otra parte, los avances en genómica han permitido establecer una nueva clasificación molecular del cáncer de mama. Nuestro objetivo es presentar una visión actualizada de la situación epidemiológica del cáncer de mama y de algunas cuestiones relevantes desde el punto de vista del diagnóstico, como son la clasificación molecular y las diferentes estrategias de cribado, poblacional y oportunista.

Numerous aspects associated with the early diagnosis and management of breast cancer have been at the centre of a great deal of scientific researches during the last decades, a fact that, when translated into the daily routine, has revolutionized the management of this condition. Some of the most significant aspects are the technological evolution of detection methods (digital mammograms, computer-assisted readings, and tomosynthesis); the development of a standardized system for the interpretation of imaging modalities; the use of less invasive surgical techniques; the improvement of systemic therapies; and the recent advances made in the field of genomics. At the same time, social awareness and the acceptance of breast cancer have increased, and the high rates of cancer incidence and mortality have made the governments of several countries develop economic resources aimed at implementing strategies of early detection.

Nevertheless, breast cancer is still the leading cause of cancer death in women, and the alleged peaks of progress achieved have been accompanied by the appearance of new risks and adverse events that, although they are hard to quantify accurately, question the real benefits that may be derived from mammography screenings.1

Our goal in this paper is to present an updated review on the epidemiological situation of breast cancer and some relevant aspects from the diagnostic point of view, such as molecular classification, and the different strategies of population and opportunistic screening programmes.

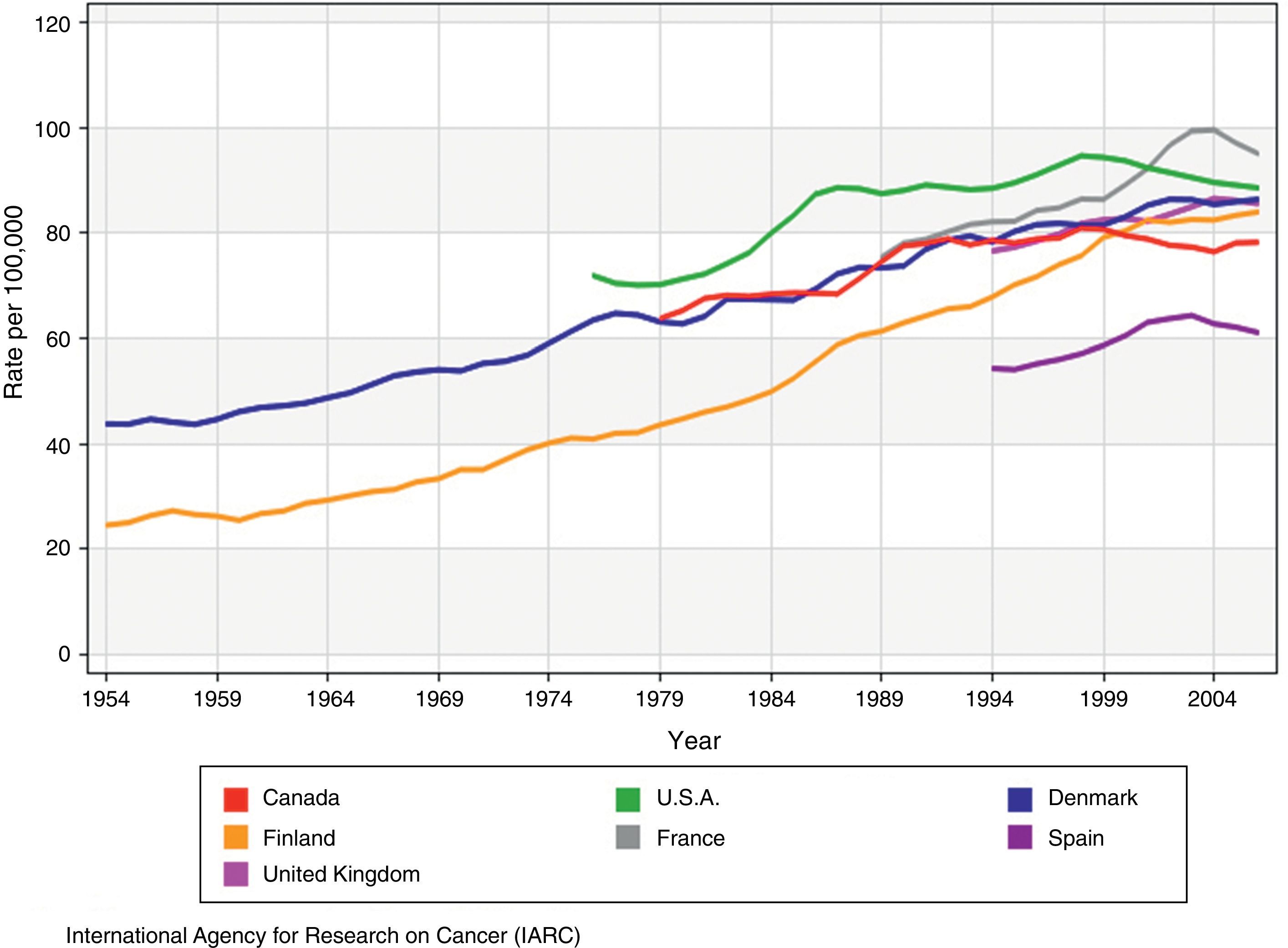

The epidemiology of breast cancerEpidemiological dataIncidenceEver since the first available records that data back to 1940,2 there has been a growing trend in the incidence of breast cancer3 (Fig. 1), with annual spikes of 1–4 per cent,4 both in developed and developing countries. This trend became more significant between the end of the 1980s and the dawn of the 21st century,5 specially in the case of early-stage in situ and invasive tumours. Ever since, we have seen the stabilization or decrease of incidence rates in most parts of Europe, United States, and Canada. In Spain, official data from the 1980–2004 period show that from 2001 onwards, the incidence of breast cancer started to decline at an annual rate of 2.4 per cent in women between 45 and 64 years of age, while in the group of women of 64 or more years of age this rate increased until 1995 at an annual rate of 3.3 per cent and, then, it stabilised.6

Incidence rates of breast cancer adjusted by age in countries with mammography screenings (adapted from the original from the IARC3).

Yet despite these facts, breast cancer is still the most common neoplasm of all in women. The odds of suffering from breast cancer increase with age, although the risk is heterogeneous in the female population and depends on a series of non-modifiable factors such as race; the confirmation through a biopsy of certain proliferative lesions (atypical hyperplasias, in situ lobular carcinomas); personal or family histories of breast cancer, or inherited genetic mutations (BRCA1, BRCA2). In the year 2012, breast cancer amounted to 25 per cent of all female cancers worldwide, surpassed only by lung cancer (both sexes combined), which translates into 25,215 new cases in Spain, and 458,718 new cases in Europe.7 By age groups, around 19 per cent of all breast cancers are diagnosed when the patient is between 30 and 49 years of age, 37 per cent when the patient is between 50 and 64 years of age, and 44 per cent in women who are, at least, 65 years old.8

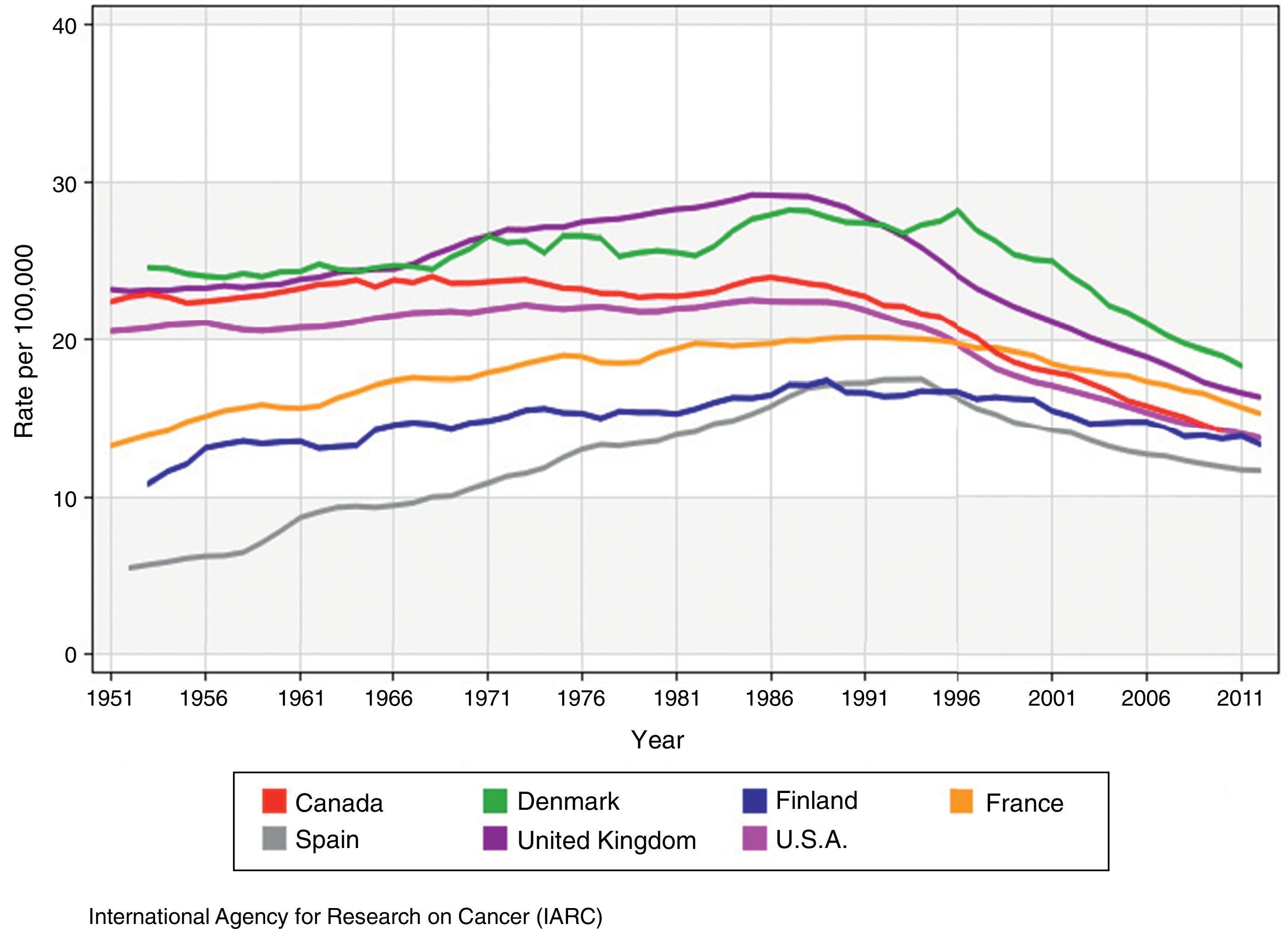

MortalityBreast cancer mortality9 (Fig. 2), experienced a long period of growth during most of the 20th century until the inflection point of 1990, when there was a trend reversal in most developed countries at an annual rate of 0.6–5.0 per cent,5 and significant increases of survival rates could be confirmed. According to estimates by the EUROCARE-5 group on the analysis of patients diagnosed with breast cancer in 29 different European countries in the 2000–2007 period, the relative rate of survival at 5 years has increased in Europe with the passage of time, with an average 81.8 per cent (76–86 per cent), reaching its maximum peak in the 45–54 year old group of patients, and gradually dropping from that age onwards.10

Mortality rates of breast cancer adjusted by age in countries with mammography screenings (adapted from the original from the IARC9).

Nevertheless, breast cancer is still the leading cause of death in women between 35 and 54 years of age. In 2012 there were 521,907 deaths worldwide – 131,347 in Europe alone.7 In Spain, where tumours are the second cause of death after circulatory system diseases, breast cancer is the leading cause of death in women, and the third overall cause of death, behind lung cancer, and colorectal cancer. In the year 2014, 6231 Spanish women died of breast cancer,11 which is a 3.8 per cent drop with respect to 2013. Spain has the lowest mortality rate of all European nations and its rates of survival exceed the average rates.

Justification of the historical trendAltered risk factorsAlthough most breast cancers are sporadic and it is not possible to prevent them, its growing incidence during the 20th century has been associated with the adverse alteration of known risk factors,12 such as the prolonged endogenous oestrogen exposure of women (early menarche, late menopause, nulliparity, or first full-term pregnancy at a late age); the ageing of population; sedentary life; alcohol consumption; obesity; exposure to ionizing radiation; and replacement hormone therapy – specially the combination of oestrogens and progestagens.13 The abandonment of the replacement hormone therapy – not very much used in Spain compared to other European countries,14 and whose effect as a risk factor increases with the duration of the therapy and is considered completely extinguished 5 years after its withdrawal,15 could partially explain the reduced incidence rates.

The role of mammography screeningsThe introduction of screening programmes in many developed countries from the late 1980s contributed to increase the incidence rates of breast cancer in the target population exponentially, not only thanks to early detection in preclinical stages of the disease, but also thanks to the diagnosis of tumours of small size and indolent biology that, in the absence of screening, would have never been clinically diagnosed,16 which has been associated with overdiagnosis. Years later, an effect of screening saturation would have initially participated in the reversal of such trend.

Much more controversial has been trying to accurately define the impact that mammography screenings have had in the progression of breast cancer mortality, yet despite that, after more than 20 years of conducting the first population screenings, the decreased mortality rates seen are consistent with what the meta-analyses of the controlled randomized trials conducted in Europe and the United States between 1963 and 1982 had predicted. On this regard, in the year 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) stated that according to the best available evidence today, mammography screenings reduce the risk of breast cancer mortality by 23 per cent in women between 50 and 69 years of age who are invited to join this programme, and by 40 per cent among the female population who really participated in such a programme17; on this regard, the IARC advocates its effectiveness in women between 40 and 49 years of age, although to a lesser degree, and supported by limited evidence.

However, for some authors, the effect that planned mammography screenings have on mortality is more modest,18 for two main reasons: (1) even though it is true that screenings have raised the number of breast cancers detected in early stages of the disease, the reduction of cases with distant metastasis has been poor in certain geographical areas19,20; and (2) even though the impact that early detection has on mortality for this reason should have been felt 7–10 years after the introduction of screening programmes, that is, at the beginning of the 21st century, in those countries that started this practice in the first place, the rapid increase of survival rates from the 1990s suggests that the periodical use of mammograms has not been the only element involved in this change of trend.16 This is why they say that the role of screening has been overestimated and that we still do not know for sure to what extent other factors such as the improvement of systemic therapies; the early detection of palpable tumours (by women themselves or during a regular physical examination); the protocolized management of breast cancer; the technological advances made in mammography screenings, more precise tumour staging and grading; or the greater availability of diagnostic tests and therapies may have also been an influence.

One relevant aspect of mammography screenings is that, regardless of the patient's age and the intrinsic biological traits of her tumour, the tumour stage still plays a significant role in the overall survival rates. This is what Saadatmand et al.’s trial21 confirmed after assessing patients with breast cancer diagnosed in Denmark during the periods of 1999–2005, and 2006–2012, that is, in both groups, mortality rates were higher together with axillary affectation and tumour size, yet despite the fact that the use of the appropriate surgical therapies and adjuvant and neoadjuvant systemic therapies was far more common in 2006–2012. Consequently, an early stage at the moment of diagnosis of breast cancer is still a non-negotiable goal.

Managing breast cancerTogether with mammography screenings, systemic therapies have been the other key factor involved in the reduced mortality rates seen in breast cancer.22 The benefit that adjuvant chemotherapy and hormone therapy have on mortality in patients with distant metastases persists from the beginning of the therapy and reaches its highest intensity after 5–15 years.23 Since their use grew and became systematic in many developed countries at the beginning of the 1980s,24 the reduced mortality rates seen during the first half of the 1990s before the introduction of population screenings or during their gradual implementation have been attributed, in particular, to the effect of adjuvant therapy. In this sense, one meta-analysis of numerous randomized trials established that, according to data collected until the year 2000, such therapies reduce the risk of relapse at 5 years and the annual mortality rates due to breast cancer at 15 years; these annual mortality rates are reduced by 38 per cent in women under 50, and by 20 per cent in women between 50 and 69 years of age.23 Another trial also states that the relative contribution of such therapies when it comes to improving mortality is greater than the relative contribution of screening in tumours with positive hormone receptors, and that, in the absence of hormone receptors, the benefit of both elements is similar.25

On the other hand, new advances in this field have been made during the first few years of the 21st century, whose impact on breast cancer mortality will be evident in the near future, such as the introduction of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the management protocols; the creation of more effective chemotherapy regimes; and the development of adjuvant biological drugs, among them, trastuzumab, that significantly improves the disease-free interval and survival of patients with HER-2 positive receptors.26

When it comes to surgical therapy, the following elective techniques have become popular: breast conservative surgery vs mastectomy, followed by adjuvant radiotherapy; and selective biopsy of the sentinel node at axillary emptying, since they decrease the risk of iatrogenia, and have the same survival rates.27,28 Also, the introduction of oncoplastic surgical techniques that combine the resection of a larger volume of tissue with better cosmetic results widened the possibilities of surgical therapy with breast conservation. However, and although we are in the age of early detection of non-palpable tumours, during the last two decades we have seen a paradoxical increase in the rate of unilateral and bilateral mastectomies, that has been even more pronounced in young candidates to conservative surgery,29 whose lifetime risk of developing contralateral neoplasms is 2–11 per cent.30 Thus, the use of prophylactic contralateral mastectomies tripled from 2002 and 2012 in U.S. patients diagnosed with stage I-III unilateral breast carcinomas, yet despite the fact that such practice associates a higher morbidity and did not associate any survival benefits.31 In an attempt to reverse this trend, the American Society of Breast Surgeons has recently published one consensus document where it recommends offering conservative surgery as long as it is feasible, together with systemic neoadjuvant therapies, or oncoplastic techniques, if needed, but does not recommend prophylactic contralateral mastectomies in medium-risk women with unilateral breast cancer.32

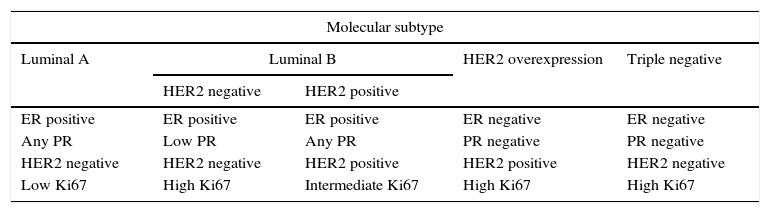

Molecular classification of breast cancerThe prognosis of breast cancerWith the experience we have accumulated through the years we have been able to confirm that not all breast cancers have a similar biological behaviour, since patients tend to have different responses to therapies and variable clinical results, yet despite being diagnosed at an identical tumour stage. At the beginning of the 21st century, the newly available genomic techniques have confirmed that there is an association between every woman's natural progression of breast cancer and their tumour gene expression profile.33,34 This has lead to establishing a new molecular classification into subtypes that is more effective than the anatomical criteria (TNM system) in order to come up with a prognosis and plan therapy individually.35 In practice, the data necessary to identify each molecular subtype are obtained preoperatively through the immunohistochemical analysis of the histological sample obtained in the percutaneous biopsy36 (Table 1).

Molecular classification of breast cancer according to immunochemistry markers.

| Molecular subtype | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luminal A | Luminal B | HER2 overexpression | Triple negative | |

| HER2 negative | HER2 positive | |||

| ER positive | ER positive | ER positive | ER negative | ER negative |

| Any PR | Low PR | Any PR | PR negative | PR negative |

| HER2 negative | HER2 negative | HER2 positive | HER2 positive | HER2 negative |

| Low Ki67 | High Ki67 | Intermediate Ki67 | High Ki67 | High Ki67 |

HER2: human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; Ki67: most common value of the Ki-67 proliferation index; ER: oestrogen receptors; PR: progesterone receptors.

Similarly, determining the tumour genotype is of great utility in patients with infiltrating breast cancer in early stages. It provides us with information on the odds of relapse and, therefore, on how convenient it is of receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. In order to conduct this proceeding included in the recommendations of the more influential oncological guidelines,37 there are different genomic tests such as Oncotype DX®; Recurrence Score®; Mammaprint®; Endopredict®; and Prosigna®, that analyse groups of genes and the activity they display. Although initially it was needed to provide fresh surgical tumour samples for study purposes, today it is possible to know the genetic profile of breast cancer with the sample from the percutaneous biopsy; this has been confirmed by López Ruiz et al.38 in the Mammaprint® platform with which they had a 84.62 per cent success rate in viable masses in the ultrasounds by using paraffin blocks of diagnostic punctures after obtaining 3–4 samples with 12G calibre needles.

Molecular subtypes: biological and imaging characteristicsLuminal AIt represents 50 per cent of all breast cancers,39 it is usually of low histological grade, and its prognosis is the most favourable of all with a 5-year survival of 80 per cent.35 The percentage of multifocal and multicentric tumours is 30–44 per cent and 9–37 per cent, respectively.40,41 Metastases usually affect the bone.42

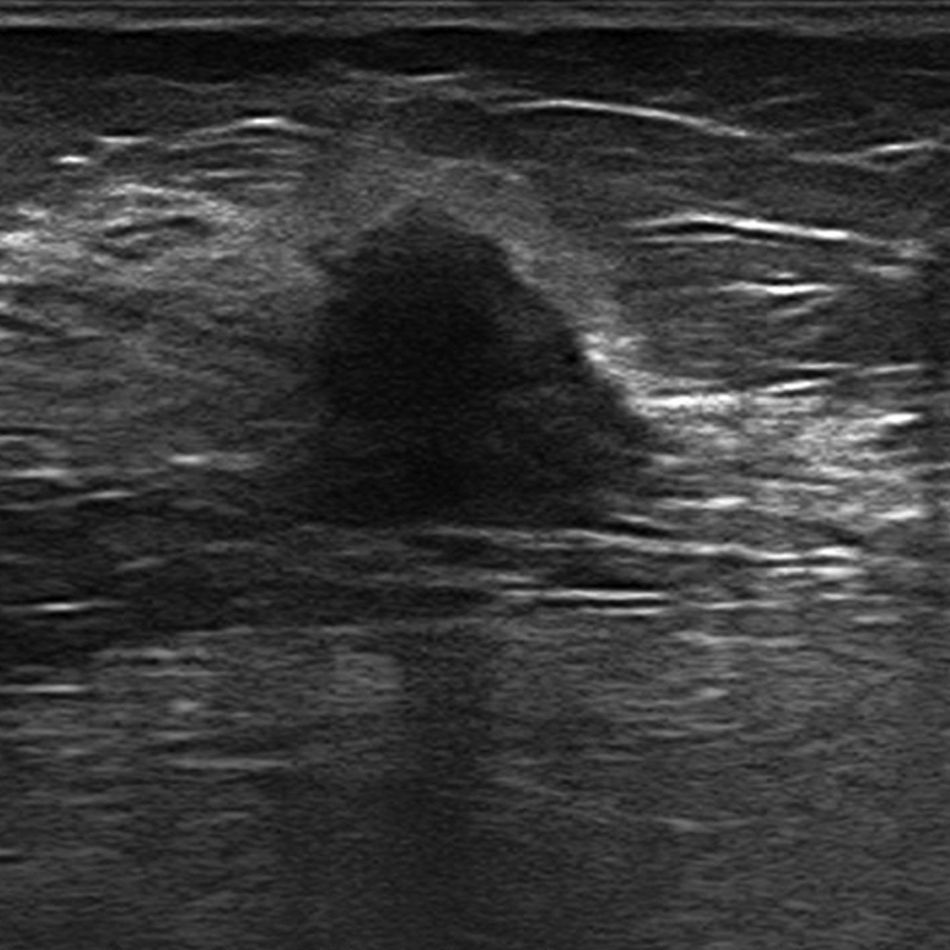

The most common mammographic finding of all is a mass-like lesion (45 per cent); other less common patterns are microcalcifications, with or without a solid component, and focal asymmetries.43 In the ultrasound, and in most of the cases, it usually appears as a hypoechogenic irregular lesion of microlobulated or angular edges, without posterior acoustic findings, with an abrupt interphase43 (Fig. 3). In the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) it usually presents as one lesion of irregular morphology, although it may look round or oval and show irregular edges, hypointensity or isointensity in the T2-weighted sequences, heterogeneous internal enhancement, and dynamic behaviour in plateau or with washout.40,44

Luminal BIts average incidence is around 15 per cent.39 Initially its survival rates at 5 years were around 40 per cent.35 In the images its traits are not different from the traits of luminal A-type neoplasms.

HER2 positiveIt represents 15–30 per cent of the total45 and corresponds to tumours of high or intermediate histological grade, with a trend towards multifocality.44,46 Survival at 5 years used to be around 31 per cent before the appearance of trastuzumab.35 Metastases affect the bones, brain, liver, and lungs.

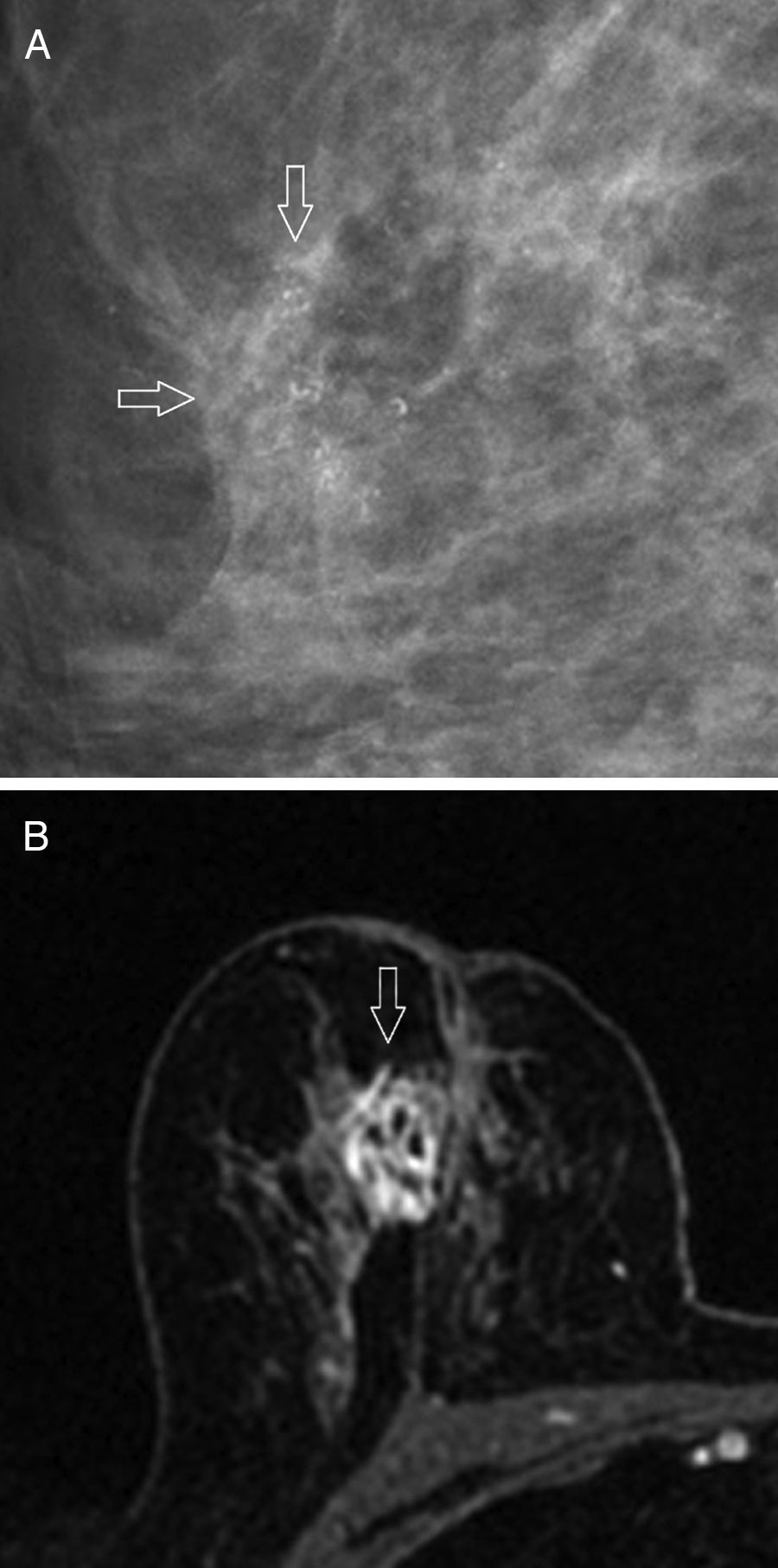

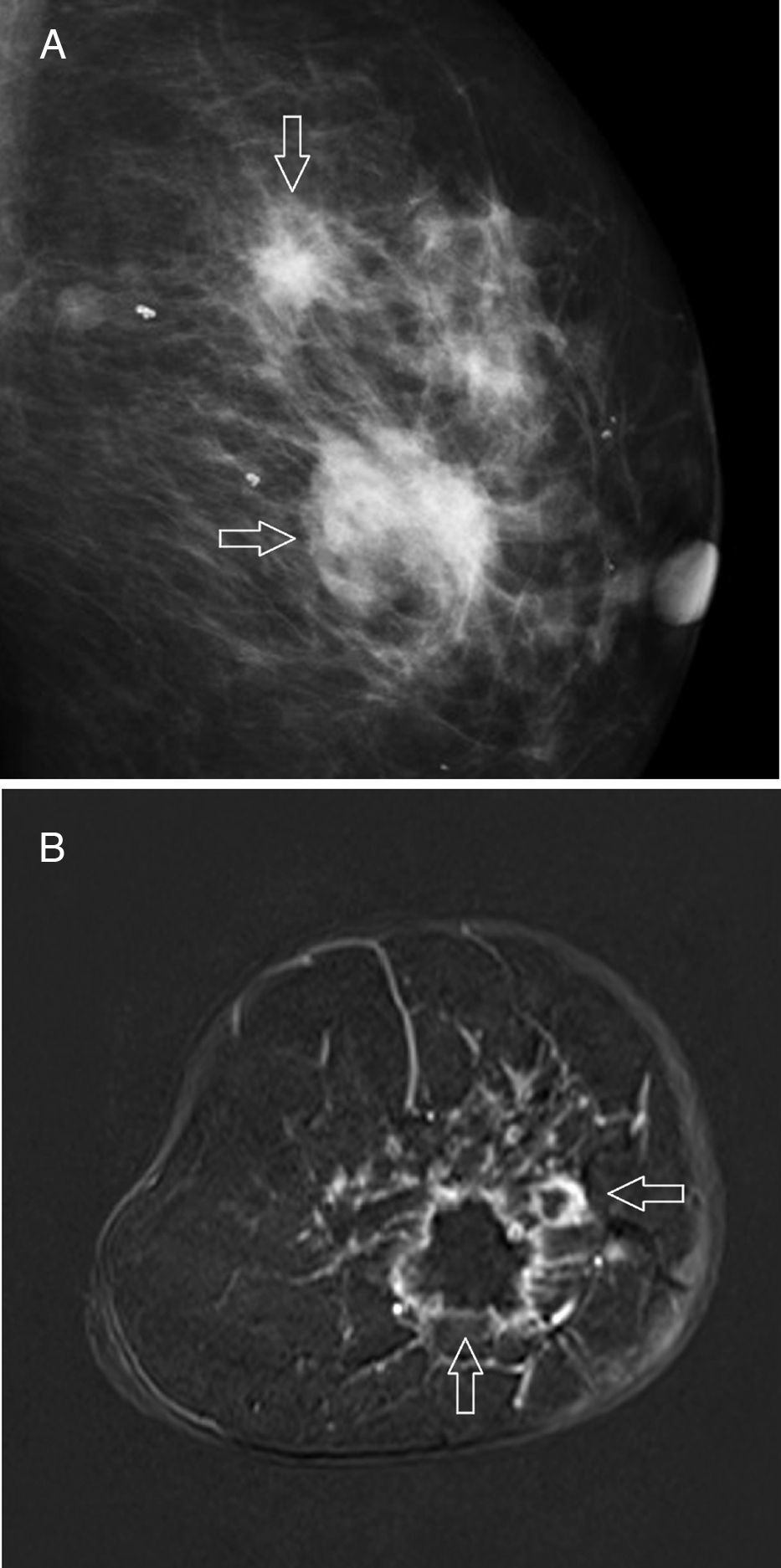

The most common mammographic findings (61–80 per cent) are pleomorphic microcalcifications,45 or thin ramified lines,46 that in most of the cases associate a mass with spiculated edges43,45 (Fig. 4A). Its common appearance in the ultrasound is that of an irregular hypoechogenic mass,45 or microlobulated or angular edges, with an abrupt interphase,43 and posterior acoustic reinforcement46; on the other hand, it manifests itself as a lesion without a detectable mass in the ultrasound – an event that occurs more frequency with this subtype than with other subtypes. The MRIs usually show one mass of irregular morphology, with speculated or irregular edges that appears hypointense or isointense in the T2-weighted images, and with heterogeneous internal enhancement44 (Fig. 4B); the dynamic study with contrast shows rapid initial enhancement with posterior washout.41,46

Triple negativeIt represents 12–17 per cent of breast cancers only,47 but it is responsible for a high percentage of deaths due to its aggressiveness.48 Its incidence is higher in Afroamerican younger women who are carriers of a BRCA1 gene mutation. They are usually unifocal neoplasms49 that when diagnosed reach larger sizes, with common axillary metastases, high histological grade, and no direct correlation between tumour size and survival,50 or the probability of axillary infiltration.49 The risk of relapse is higher during the first 1–4 years of follow-up, above all in lungs and brain,47 but from the 10th year onwards, the risk of relapse drops to a lower level than that of patients with tumours expressing oestrogen receptors.51 Unlike the rest, its sensitivity to neoadjuvant chemotherapy is higher, and prognosis looks better after a complete response.52 Many interval cancers correspond to this subtype,53 most of which are detected clinically, which has been associated with rapid tumour growth and high breast density in the mammography – more common at younger ages.

In the mammography, the most characteristic pattern is an oval, lobulated, or round mass with poorly established edges and without associated microcalcifications45,54 (Fig. 5A); irregular shapes and spiculated edges53 are less common. In the ultrasound it usually looks like an irregular hypoechogenic mass of heterogeneous structure43; however, in 15–20 per cent of the patients its appearance may be misleading and initially lead us to think of benignity,55 since it shows a round or oval shape, well established edges,45,53 and posterior acoustic reinforcement.43 The most common findings in the MRI40,41,44,55,56 are a round or oval mass with well established edges (39–71 per cent), that show intratumor hyperintensity in the T2-weighted sequences due to the existence of intratumor necrosis (46–66 per cent), showing ring enhancement pattern in 46–80 per cent of the cases (Fig. 5B), while exhibiting kinetic behaviour in plateau or with washout.

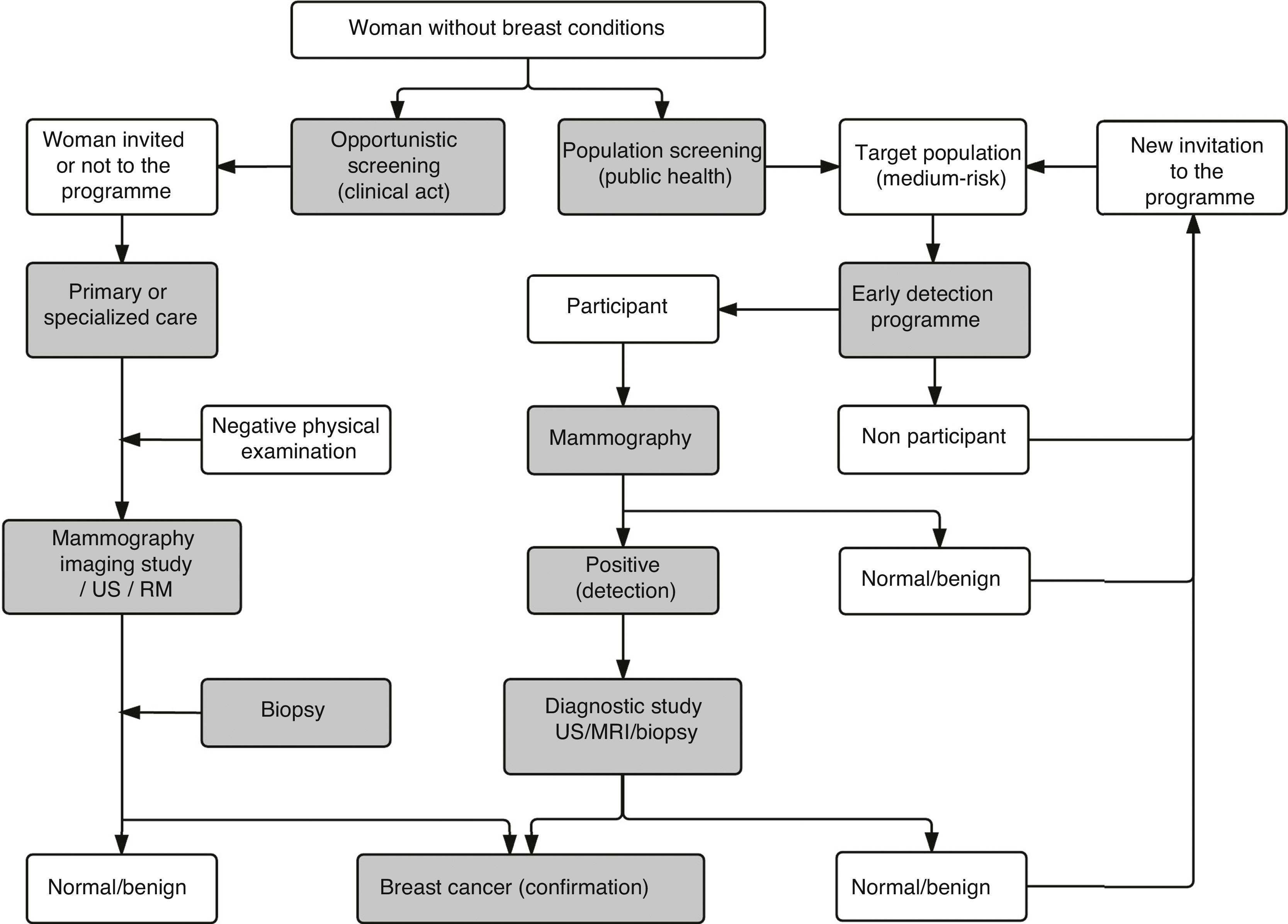

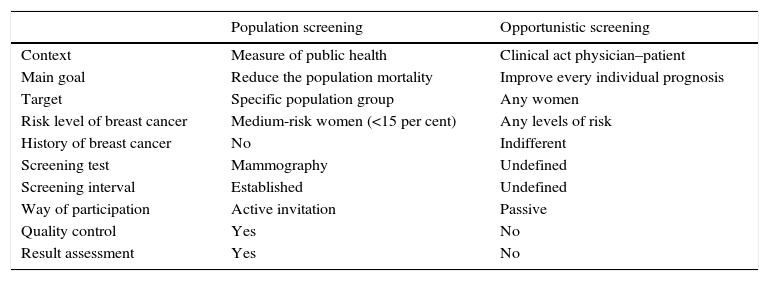

The mammography screening of breast cancerScreening strategies: population and opportunisticThe concept of screening includes the application of selection methods to people who are apparently healthy in order to detect those who may suffer from this or that medical condition in a pre-clinical stage, and that would need additional tests to confirm or rule out the diagnosis.57 There are two (2) different screening strategies in breast cancer: population and opportunistic. Table 2 shows their main differential aspects, while the activities that make up their respective process are shown in Fig. 6.

Main characteristics of population screening and opportunistic screening of breast cancer.

| Population screening | Opportunistic screening | |

|---|---|---|

| Context | Measure of public health | Clinical act physician–patient |

| Main goal | Reduce the population mortality | Improve every individual prognosis |

| Target | Specific population group | Any women |

| Risk level of breast cancer | Medium-risk women (<15 per cent) | Any levels of risk |

| History of breast cancer | No | Indifferent |

| Screening test | Mammography | Undefined |

| Screening interval | Established | Undefined |

| Way of participation | Active invitation | Passive |

| Quality control | Yes | No |

| Result assessment | Yes | No |

In most European countries both modalities coexist together. Unlike population screening that has been studied in numerous trials, the opportunistic screening is supported by little evidence. In particular in Switzerland, several researches have been conducting opportunistic screenings with mammograms and they have come to the conclusion that, although the effectiveness of both strategies is similar when conducted simultaneously in the same geographical region, the results are not as good when only the opportunistic screening is available.58 When it comes to conducting opportunistic screenings only, Bordoni et al.59 saw that the indicators required by the screening programmes such as a certain percentage of in situ cancers, and invasive cancers ≤10mm in size, without axillary metastases or in stage ≥II were not being met. de Gelder et al.60 informed that, in this country, every year of life gained against breast cancer with opportunistic screenings doubled the economic cost compared to population screenings. In one Spanish autonomous community, one trial showed that between 2003 and 2006, the opportunistic screening was requested by half the patients from the breast cancer units where population screenings were the routine practice, which translated into one third of the activity performed there and a high cost compared to the latter, yet it only detected 6.3 per cent of diagnosed cancers.61 Vanier et al.62 claimed that in French women between 50 and 74 years of age from a certain region, the breast cancers diagnosed through opportunistic screenings showed earlier stages than the ones diagnosed clinically. On the other hand, it has also been published that the sensitivity of the mammography is higher when conducted in a context of population screenings.63 One essential fact that advocates for screening programmes is that they not only guarantee the equality of access to mammograms but also achieve higher rates of participation, specially among women of higher socioeconomic status.64,65

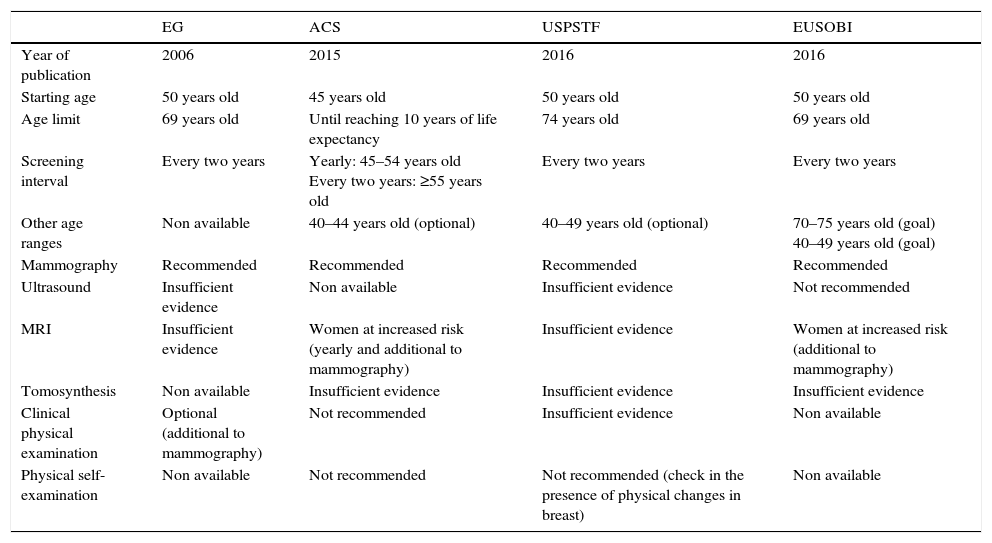

Screening programmes: international recommendationsThe fourth edition of the European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Mammography Screening,66 published in 2006 and a model for this practice in our setting has been recently accompanied by updates of the clinical guidelines published by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force,67 and the American Cancer Society,68 and the position paper published by the European Society of Breast Imaging.69 All these recommendations are focused on maximizing the benefits of screenings, specially when it comes to reducing mortality and years of life gained, and at the same time, minimizing the risks and adverse events derived from such screenings, among which we find overdiagnosis [estimated at an average 6.5 per cent (1–10 per cent)] in European women between 50 and 79 years of age who participated in ten rounds.70,71 All the aforementioned documents are consistent with the claim that mammograms are the only imaging modality recommended for screening medium-risk women and include an age range between 50 and 69 years of age in the target population but do not recommend physical examinations by healthcare personnel or the patient herself (Table 3). While these documents do not agree on the starting ages, age limits, or screening intervals, most do agree on conducting screenings every two years. Although the prognosis of a patient diagnosed with breast cancer through a population screening is more favourable and her chances of dying due to this type of cancer are 50 per cent lower compared to when the diagnosis is achieved in a clinical stage,72 the women invited to join the programme should have enough information in order to be able to make an informed decision on their own participation.

International recommendations on population screenings of breast cancer.

| EG | ACS | USPSTF | EUSOBI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of publication | 2006 | 2015 | 2016 | 2016 |

| Starting age | 50 years old | 45 years old | 50 years old | 50 years old |

| Age limit | 69 years old | Until reaching 10 years of life expectancy | 74 years old | 69 years old |

| Screening interval | Every two years | Yearly: 45–54 years old Every two years: ≥55 years old | Every two years | Every two years |

| Other age ranges | Non available | 40–44 years old (optional) | 40–49 years old (optional) | 70–75 years old (goal) 40–49 years old (goal) |

| Mammography | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended |

| Ultrasound | Insufficient evidence | Non available | Insufficient evidence | Not recommended |

| MRI | Insufficient evidence | Women at increased risk (yearly and additional to mammography) | Insufficient evidence | Women at increased risk (additional to mammography) |

| Tomosynthesis | Non available | Insufficient evidence | Insufficient evidence | Insufficient evidence |

| Clinical physical examination | Optional (additional to mammography) | Not recommended | Insufficient evidence | Non available |

| Physical self-examination | Non available | Not recommended | Not recommended (check in the presence of physical changes in breast) | Non available |

In the year 2013 the fifth edition of the BI-RADS® (Breast Imaging Reporting And Data System)73 was published – the classification that has standardized the language of radiology reports and allowed us to assign one category of tumour suspicious for carcinoma to a certain finding, plus one associated recommendation for acting accordingly. In order to reduce the intra and inter-observer variability inherent to any systems based on individual perception74 and causing the overlapping of the lesions assigned to each category,75 in the actual edition, the specific vocabulary of mammography, ultrasound, and MRI has been reviewed, and a larger number of graphic resources, plus two sections on follow-up and monitoring of the results have been included.

ConclusionThe combined actions of early detection with mammograms plus the routine use of adjuvant therapies has been a determinant factor in the more favourable evolution of mortality of breast cancer patients during the last few decades. It has also been confirmed that the prognosis of every woman is closely related to the genetic profile of their respective tumours and that, although the findings from the imaging modalities are non-specific, there are cases where some peculiar traits may be identified that will lead us to a certain molecular subtype. In the future, it is expected that we will have new evidence that will make us keep advancing in the management of this condition.

Authors- 1.

Manager of the integrity of the study: JAMB.

- 2.

Study idea: JAMB, MTT and LHRM.

- 3.

Study design: JAMB and MTT.

- 4.

Data mining: N/A.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: N/A.

- 6.

Statistical analysis: N/A.

- 7.

Reference: JAMB.

- 8.

Writing: JAMB.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant remarks: MTT and LHRM.

- 10.

Approval of final version: all authors have read and approved the final version of this paper.

The authors declare that no experiments with human beings or animals have been performed while conducting this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors confirm that in this article there are no data from patients.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors confirm that in this article there are no data from patients.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interests associated with this article whatsoever.

To Mr. Javier Barbero Fernández, for his unconditional help editing the images included in this paper.

Please cite this article as: Merino Bonilla JA, Torres Tabanera M, Ros Mendoza LH. El cáncer de mama en el siglo XXI: de la detección precoz a los nuevos tratamientos. Radiología. 2017;59:368–379.