To analyze the anatomic characteristics of the left atrium and pulmonary veins in individuals undergoing ablation for atrial fibrillation and to identify possible anatomic factors related with recurrence.

Material and methodsWe retrospectively reviewed the CT angiography studies done to plan radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation in 95 patients (57 men; mean age, 65 ± 10 y). We reviewed the anatomy of the pulmonary veins and recorded the diameters of their ostia as well as the diameter and volume of the left atrium. We analyzed these parameters according to the type of arrhythmia and the response to treatment.

ResultsIn 71 (74.7%) patients, the anatomy of the pulmonary veins was normal (i.e., two right pulmonary veins and two left pulmonary veins). Compared to patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, patients with persistent atrial fibrillation had slightly larger diameter of the left pulmonary veins (left superior pulmonary vein 17.9 ± 2.6 mm vs. 16.7 ± 2.2 mm, p = 0.04; left inferior pulmonary vein 15.3 ± 2 mm vs. 13.8 ± 2.2 mm, p = 0.009) and larger left atrial volume (91.9 ± 24.9 cm3 vs. 70.7 ± 20.3 mm3, p = 0.001). After 22.1 ± 12.1 months’ mean follow-up, 41 patients had sinus rhythm. Compared to patients in whom the sinus rhythm was restored, patients with recurrence had greater left atrial volume (81.4 ± 23.0 mm3 vs. 71.1 ± 23.2 mm3, p = 0.03). No significant differences in pulmonary vein diameters or clinical parameters were observed between patients with recurrence and those without.

ConclusionThe volume of the left atrium is greater in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation and in those who do not respond to ablation.

Definir las características anatómicas de la aurícula izquierda y las venas pulmonares (VP) en sujetos sometidos a ablación de fibrilación auricular (FA) e identificar posibles factores anatómicos relacionados con la recurrencia.

Material y métodosSe estudiaron de manera retrospectiva los estudios de angio-TC de 95 pacientes (57 hombres, edad media 65 ± 10 años), realizados para planificación de ablación por radiofrecuencia de FA. Se revisó la anatomía de las VP y se recogieron los diámetros de sus ostium y los diámetros y volumen de la aurícula izquierda. Estos parámetros fueron comparados con el tipo de arritmia y la respuesta al tratamiento.

ResultadosLa anatomía de las venas pulmonares fue normal (dos venas pulmonares derechas y dos izquierdas) en la mayoría de los pacientes (74,7%). Los pacientes con FA persistente presentaron diámetros ligeramente superiores de las venas pulmonares izquierdas (VPSI de 17,9 ± 2,6 mm vs. 16,7 ± 2,2 mm, p = 0,04; VPII de 15,3 ± 2 mm vs. 13,8 ± 2,2 mm, p = 0,009) y mayor volumen de la aurícula izquierda (91,9 ± 24,9 cm3 vs. 70,7 ± 20,3 mm3, p = 0,001) que los sujetos con FA paroxística. Tras un seguimiento medio de 22,1 ± 12,1 meses, el 43% de los pacientes presentaba ritmo sinusal. Los pacientes con recurrencia mostraron mayor volumen de la aurícula izquierda (81,4 ± 23 mm3 vs. 71,1 ± 23,2 mm3, p = 0,03). No se objetivaron diferencias significativas en los diámetros de las VP ni en los parámetros clínicos estudiados en ambos grupos.

ConclusiónEl volumen de la aurícula izquierda es mayor en pacientes con FA persistente y en pacientes que no responden al procedimiento de ablación.

The best way to comply with funding policies is to declare the funding entity for your research and the grant received. We were unable to locate any reference to the funding for your research in your manuscript. Please confirm that this is correct. If you would like to declare a funding entity for your research, please specify the entity's full name and country and the IDs for the grant in the text of your article. Ablation is a procedure that is usually planned using a computed tomography (CT) angiogram. This techniques enables the number, size and location of the pulmonary veins to be determined in great anatomical detail. It also allows clinicians to examine the anatomy of the left ventricle, measure its size and rule out the presence of thrombi.4 This study was conducted with the objective of determining the anatomical characteristics of the pulmonary veins and the left atrium in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) and ascertaining whether any imaging data may predict the success of ablation or establish risk factors for recurrence.

Material and methodsPatientsThe study retrospectively enrolled 95 patients who underwent a computed tomography (CT) angiogram prior to ablation for atrial arrhythmias (AF, flutter, atrial tachycardia) in 2015. It excluded patients having undergone ablation in prior years, haemodynamically unstable patients and patients with classic contraindications for CT such as chronic kidney disease (serum creatinine >1.4 mg/dl) and a history of allergic reaction to iodinated contrast.

Informed consent was obtained in writing from all individuals. The study was approved by the independent ethics committee at our centre.

CT angiogram protocolCT angiograms were performed with a dual-source CT scanner (SOMATOM Definition, Siemens Healthineers, Forchheim, Germany) with the patient in the supine decubitus position, on inspiration, craniocaudally, in a range extending from the middle of the aortic arch to the end of the heart, and with retrospective electrocardiogram (ECG) synchronisation. The following acquisition parameters were used: 120 kVp, 350 mA for each tube, a slice thickness of 64 × 0.6 mm, collimation of 64 × 0.6 mm, a gantry rotation time of 330 ms and temporal resolution (83 ms). A variable pitch (0.2−0.45) adapted to the heart rate was used. The tube current was automatically modulated (ECG pulsing), with administration of a maximum dose of radiation between 30% and 80% of the cardiac cycle and reduction of the nominal tube current to 25% in all other cardiac cycle phases.

Patients were injected with 80 ml of intravenous iodinated contrast (Iomeron 400, Iomeprol, Bracco S.p.A, Milan, Italy) at a rate of 4 ml/s, followed by a bolus of 50 ml of normal saline, through a dual-syringe injector (CT Stellant, Medrad Inc., Indianola, United States), using the automated bolus technique and a firing threshold of 100 Hounsfield units (HUs).

The images were reconstructed with a slice thickness of 0.75 mm, a reconstruction increase of 0.4 mm, a single-segment reconstruction algorithm, a soft-tissue filter (B26f) and a matrix of 512 × 512 pixels. To reconstruct the images and evaluate the anatomy of the pulmonary veins, a diastolic phase was selected in patients who had a heart rate lower than 60 beats per minute (bpm), and a systolic phase was selected in patients who had a heart rate higher than 60 bpm or who presented an arrhythmia. The diameters of the pulmonary veins and the volume of the left atrium were calculated in a systolic reconstruction.

No patients were excluded from the study due to arrhythmia or irregular heart rhythm, nor were beta blockers used to reduce heart rate. All CT angiograms were performed no more than one week from the ablation procedure. The studies were stored in the hospital's picture archiving and communication system (PACS).

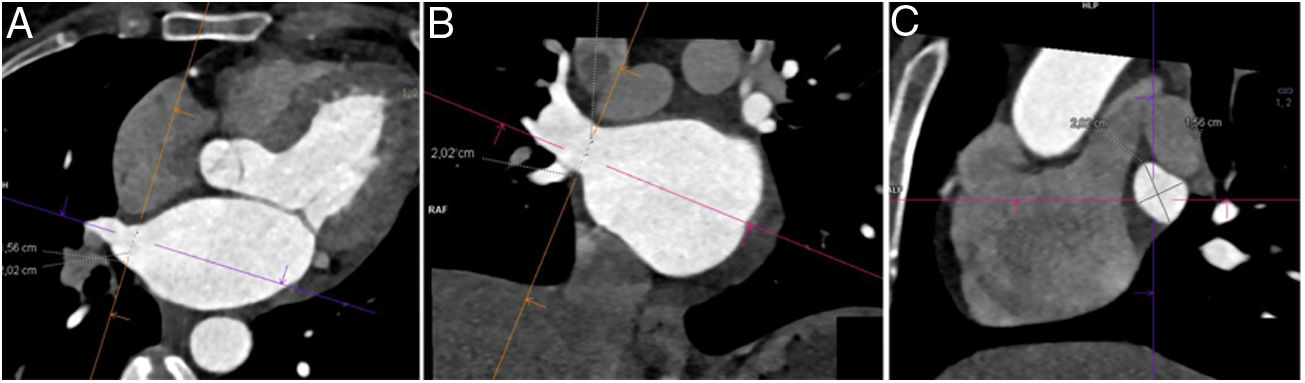

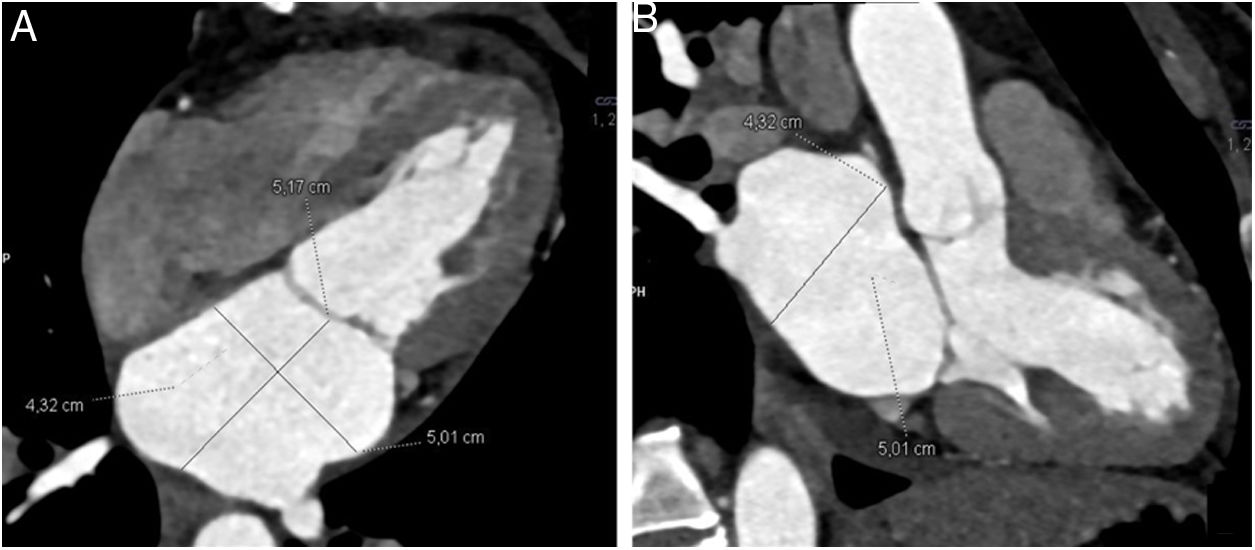

Image analysisPost-processing of images was performed at a workstation equipped with a specific program capable of multiplanar and volumetric reconstructions (MM Reading, Syngo.via, Siemens Healthineers). Normal anatomy was defined as the presence of two left pulmonary veins and two right pulmonary veins that drained into the left atrium. Among anatomical variants, an accessory pulmonary vein was defined as one that independently drained from the main pulmonary veins to the left atrium and was named in accordance with the pulmonary segment from which it drained. A common venous drainage trunk was considered to be present when the superior and inferior pulmonary veins joined for at least 5 mm before emptying into the left atrium.5 The diameters of the ostia of the pulmonary veins (right superior pulmonary vein [RSPV], right inferior pulmonary vein [RIPV], left superior pulmonary vein [LSPV] and left inferior pulmonary vein [LIPV]) were measured less than 1 cm from their entrance into the left atrium, on a double-oblique perpendicular plane, along the main axis of each pulmonary vein (Fig. 1). The diameters of the left atrium were measured on the four-chamber view and on the three-chamber view of the left ventricle (Fig. 2). The volume of the left atrium was calculated using the following equation: Vol. = (D1 × D2 × D3) × (0.523), where D1 is the transverse diameter on the four-chamber view, D2 is the anteroposterior diameter on the four-chamber view and D3 is the craniocaudal diameter on the three-chamber view.6 The atrial appendage was excluded from the volume calculation.

Measurement of the diameters of the pulmonary veins. After tracing orthogonal planes in the axial images (A) and coronal images (B) from computed tomography, a double-oblique image of the ostium of the pulmonary vein (C) was obtained, on which the diameters were measured. The example shows the diameters of the right superior pulmonary vein.

The following were collected in all patients: demographic data, heart rate, blood pressure, cardiovascular risk factors and other variables such as age at first episode of arrhythmia, type of arrhythmia, complications of ablation, recurrence and time free from arrhythmia. Blanking-period recurrences were defined as recurrences that appeared in the first three months subsequent to ablation.7 In this period, recurrence of arrhythmias could be attributed to inflammatory changes occurring in the atrium after the procedure and not necessarily predictive of late recurrence of arrhythmias. Definitive recurrences were defined as arrhythmias that reappeared after three months had elapsed since ablation. The imaging variables that were collected were the diameters of the ostia of the pulmonary veins, the diameters of the left atrium and the left atrial volume.

Statistical analysisThe data are presented in terms of mean ± standard deviation or frequencies, depending on their nature. The normal distribution of the data was confirmed with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Student's t-tests were used for independent or paired samples to compare continuous quantitative variables, and the χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables. Statistical analysis of the data was performed using the SPSS program (IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac, version 20.0). A p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

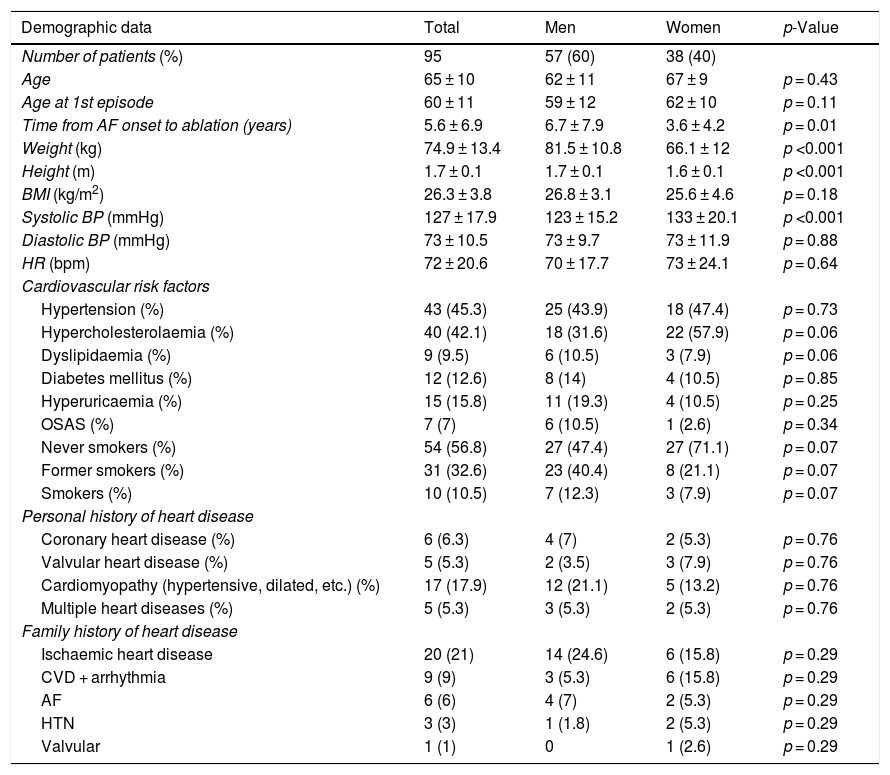

ResultsPatientsA CT angiogram was performed prior to the ablation procedure in 95 patients (57 men and 38 women, with a mean age of 65 ± 10 years). The mean age at onset of the first episode of arrhythmia was 60 ± 11 years. The most common arrhythmias were paroxysmal AF (43.2%), persistent AF (30.5%) and paroxysmal AF with flutter (14.7%). The mean age of patients with paroxysmal AF (66 ± 9 years) and persistent AF (66 ± 10 years) and the profile of cardiovascular risk factors between the two groups were similar. The mean duration of AF from the first episode to ablation was 5.6 ± 6.9 years. Table 1 summarises the demographic data, cardiovascular risk factors and personal and family histories of heart disease for the subjects enrolled in the study.

Demographic data, cardiovascular risk factors and personal and family history of heart disease in the study population. Differences between men and women are compared.

| Demographic data | Total | Men | Women | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (%) | 95 | 57 (60) | 38 (40) | |

| Age | 65 ± 10 | 62 ± 11 | 67 ± 9 | p = 0.43 |

| Age at 1st episode | 60 ± 11 | 59 ± 12 | 62 ± 10 | p = 0.11 |

| Time from AF onset to ablation (years) | 5.6 ± 6.9 | 6.7 ± 7.9 | 3.6 ± 4.2 | p = 0.01 |

| Weight (kg) | 74.9 ± 13.4 | 81.5 ± 10.8 | 66.1 ± 12 | p <0.001 |

| Height (m) | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | p <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.3 ± 3.8 | 26.8 ± 3.1 | 25.6 ± 4.6 | p = 0.18 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 127 ± 17.9 | 123 ± 15.2 | 133 ± 20.1 | p <0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 73 ± 10.5 | 73 ± 9.7 | 73 ± 11.9 | p = 0.88 |

| HR (bpm) | 72 ± 20.6 | 70 ± 17.7 | 73 ± 24.1 | p = 0.64 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||||

| Hypertension (%) | 43 (45.3) | 25 (43.9) | 18 (47.4) | p = 0.73 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia (%) | 40 (42.1) | 18 (31.6) | 22 (57.9) | p = 0.06 |

| Dyslipidaemia (%) | 9 (9.5) | 6 (10.5) | 3 (7.9) | p = 0.06 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 12 (12.6) | 8 (14) | 4 (10.5) | p = 0.85 |

| Hyperuricaemia (%) | 15 (15.8) | 11 (19.3) | 4 (10.5) | p = 0.25 |

| OSAS (%) | 7 (7) | 6 (10.5) | 1 (2.6) | p = 0.34 |

| Never smokers (%) | 54 (56.8) | 27 (47.4) | 27 (71.1) | p = 0.07 |

| Former smokers (%) | 31 (32.6) | 23 (40.4) | 8 (21.1) | p = 0.07 |

| Smokers (%) | 10 (10.5) | 7 (12.3) | 3 (7.9) | p = 0.07 |

| Personal history of heart disease | ||||

| Coronary heart disease (%) | 6 (6.3) | 4 (7) | 2 (5.3) | p = 0.76 |

| Valvular heart disease (%) | 5 (5.3) | 2 (3.5) | 3 (7.9) | p = 0.76 |

| Cardiomyopathy (hypertensive, dilated, etc.) (%) | 17 (17.9) | 12 (21.1) | 5 (13.2) | p = 0.76 |

| Multiple heart diseases (%) | 5 (5.3) | 3 (5.3) | 2 (5.3) | p = 0.76 |

| Family history of heart disease | ||||

| Ischaemic heart disease | 20 (21) | 14 (24.6) | 6 (15.8) | p = 0.29 |

| CVD + arrhythmia | 9 (9) | 3 (5.3) | 6 (15.8) | p = 0.29 |

| AF | 6 (6) | 4 (7) | 2 (5.3) | p = 0.29 |

| HTN | 3 (3) | 1 (1.8) | 2 (5.3) | p = 0.29 |

| Valvular | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (2.6) | p = 0.29 |

Note: Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation and as percentages.

AF: atrial fibrillation; BMI: body mass index; BP: blood pressure; CVD: cardiovascular disease; HR: heart rate; HTN: hypertension; OSAS: obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome.

The mean dose length product (DLP) was 694.1 ± 273.6 mGy*cm, equivalent to a mean effective radiation dose of 9.7 ± 8.8 mSv (conversion factor k = 0.014 mSv/mGy/cm).8

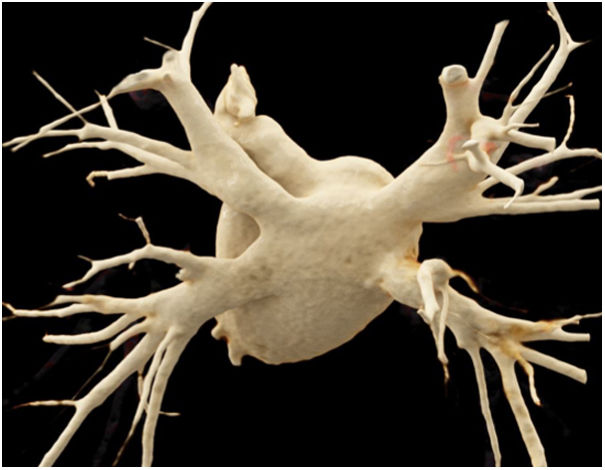

Anatomy of the left atrium and of the pulmonary veins in the pre-ablation studiesThe anatomy of the pulmonary veins was normal in most of the patients enrolled in the study (71 patients) (Fig. 3). The anatomical variants seen were a right accessory vein, corresponding to independent drainage of the middle lobe vein into the left atrium (13 patients), a common left trunk for venous drainage (8 patients), a right accessory vein together with a common left trunk for venous drainage (2 patients) and two common trunks for venous drainage (1 patient).

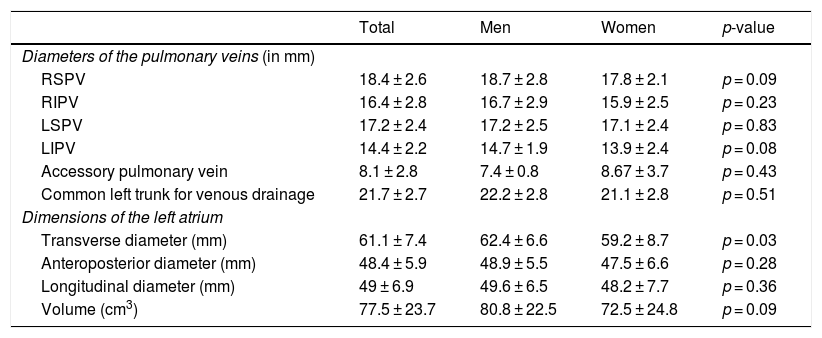

Table 2 summarises the diameters of the pulmonary veins and the diameters and volumes of the left atrium acquired in CT angiography. The superior pulmonary veins were larger than the inferior pulmonary veins; the left inferior pulmonary vein was the smallest vein. No significant differences were seen in the diameters of the pulmonary veins between men and women. The mean left atrial volume was 77.5 ± 23.7 cm3, and was similar in both sexes (80.8 ± 22.5 cm3 for men and 72.5 ± 24.8 cm3 for women; p = 0.09; 95% confidence interval [CI]: −15.6, 17.9).

Diameters of the pulmonary veins and diameters and volumes of the left atrium in men and women. Differences between the sexes are compared.

| Total | Men | Women | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameters of the pulmonary veins (in mm) | ||||

| RSPV | 18.4 ± 2.6 | 18.7 ± 2.8 | 17.8 ± 2.1 | p = 0.09 |

| RIPV | 16.4 ± 2.8 | 16.7 ± 2.9 | 15.9 ± 2.5 | p = 0.23 |

| LSPV | 17.2 ± 2.4 | 17.2 ± 2.5 | 17.1 ± 2.4 | p = 0.83 |

| LIPV | 14.4 ± 2.2 | 14.7 ± 1.9 | 13.9 ± 2.4 | p = 0.08 |

| Accessory pulmonary vein | 8.1 ± 2.8 | 7.4 ± 0.8 | 8.67 ± 3.7 | p = 0.43 |

| Common left trunk for venous drainage | 21.7 ± 2.7 | 22.2 ± 2.8 | 21.1 ± 2.8 | p = 0.51 |

| Dimensions of the left atrium | ||||

| Transverse diameter (mm) | 61.1 ± 7.4 | 62.4 ± 6.6 | 59.2 ± 8.7 | p = 0.03 |

| Anteroposterior diameter (mm) | 48.4 ± 5.9 | 48.9 ± 5.5 | 47.5 ± 6.6 | p = 0.28 |

| Longitudinal diameter (mm) | 49 ± 6.9 | 49.6 ± 6.5 | 48.2 ± 7.7 | p = 0.36 |

| Volume (cm3) | 77.5 ± 23.7 | 80.8 ± 22.5 | 72.5 ± 24.8 | p = 0.09 |

LIPV: left inferior pulmonary vein; LSPV: left superior pulmonary vein; RIPV: right inferior pulmonary vein; RSPV: right superior pulmonary vein.

By type of arrhythmia, no differences were observed in pulmonary vein anatomy between patients with paroxysmal AF and persistent AF, although patients with persistent AF had left pulmonary veins with slightly larger dimensions (LSPV 17.9 ± 2.6 mm versus 16.7 ± 2.2 mm; p = 0.04; 95% CI: −2.2, −0.4); LIPV 15.3±2 mm versus 13.8±2.2 mm; p = 0.009; 95% CI: −2.4, −0.4). Patients with persistent AF also showed a higher left atrial volume (91.9 ± 24.9 cm3) than patients with paroxysmal AF (70.7 ± 20.3 cm3) (p = 0.001; 95% CI: −28.4, −87.7).

Clinical outcome of ablationSubsequent to a mean follow-up period after the ablation procedure of 22.1 ± 12.1 months, it was observed that 41 patients (43%) now had a sinus rhythm. Arrhythmia recurrence was seen in 48 subjects (51%): 16 blanking-period recurrences (mean time 1.2 ± 0.6 months) and 32 late recurrences (mean time 14.2 ± 13.1 months). Another ablation procedure was performed in 42 subjects, with success in 27 (64.3%) and another recurrence in 15 (15.8%). No follow-up data were available for six patients.

When the groups were compared according to ablation procedure efficacy, no statistically significant differences were found in terms of age, sex, cardiovascular risk factors, type of arrhythmia, age at onset of first episode of AF or duration of arrhythmia.

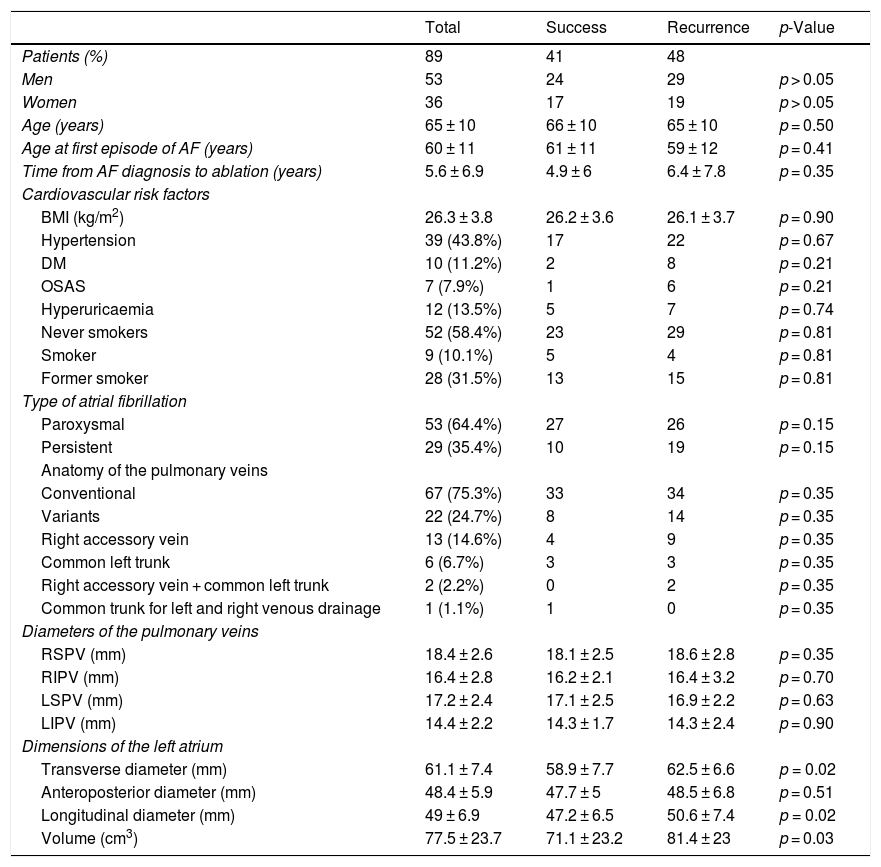

From a morphological perspective, the anatomy and dimensions of the pulmonary veins were similar in the two groups; the only difference observed was that patients with recurrence presented larger transverse diameters (62.5 ± 6.6 mm versus 58.9 ± 7.7 mm; p = 0.02; 95% CI: −6.6, −0.6) and longitudinal diameters (50.6±7.4 mm versus 47.2 ± 6.5 mm; p = 0.02; 95% CI: −6.3, −0.4) for the left atrium. In these patients, left atrial volume was also higher (81.4 ± 23 mm3 versus 71.1 ± 23.2 mm3; p = 0.03; 95% CI: −20, −50.6) (Table 3).

Differences in demographic characteristics, type of arrhythmia, cardiovascular risk factors and anatomical characteristics and diameters of the pulmonary veins and diameters and volume of the left atrium by ablation outcome. Outcomes between procedure success and arrhythmia recurrence following ablation are compared.

| Total | Success | Recurrence | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (%) | 89 | 41 | 48 | |

| Men | 53 | 24 | 29 | p > 0.05 |

| Women | 36 | 17 | 19 | p > 0.05 |

| Age (years) | 65 ± 10 | 66 ± 10 | 65 ± 10 | p = 0.50 |

| Age at first episode of AF (years) | 60 ± 11 | 61 ± 11 | 59 ± 12 | p = 0.41 |

| Time from AF diagnosis to ablation (years) | 5.6 ± 6.9 | 4.9 ± 6 | 6.4 ± 7.8 | p = 0.35 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.3 ± 3.8 | 26.2 ± 3.6 | 26.1 ± 3.7 | p = 0.90 |

| Hypertension | 39 (43.8%) | 17 | 22 | p = 0.67 |

| DM | 10 (11.2%) | 2 | 8 | p = 0.21 |

| OSAS | 7 (7.9%) | 1 | 6 | p = 0.21 |

| Hyperuricaemia | 12 (13.5%) | 5 | 7 | p = 0.74 |

| Never smokers | 52 (58.4%) | 23 | 29 | p = 0.81 |

| Smoker | 9 (10.1%) | 5 | 4 | p = 0.81 |

| Former smoker | 28 (31.5%) | 13 | 15 | p = 0.81 |

| Type of atrial fibrillation | ||||

| Paroxysmal | 53 (64.4%) | 27 | 26 | p = 0.15 |

| Persistent | 29 (35.4%) | 10 | 19 | p = 0.15 |

| Anatomy of the pulmonary veins | ||||

| Conventional | 67 (75.3%) | 33 | 34 | p = 0.35 |

| Variants | 22 (24.7%) | 8 | 14 | p = 0.35 |

| Right accessory vein | 13 (14.6%) | 4 | 9 | p = 0.35 |

| Common left trunk | 6 (6.7%) | 3 | 3 | p = 0.35 |

| Right accessory vein + common left trunk | 2 (2.2%) | 0 | 2 | p = 0.35 |

| Common trunk for left and right venous drainage | 1 (1.1%) | 1 | 0 | p = 0.35 |

| Diameters of the pulmonary veins | ||||

| RSPV (mm) | 18.4 ± 2.6 | 18.1 ± 2.5 | 18.6 ± 2.8 | p = 0.35 |

| RIPV (mm) | 16.4 ± 2.8 | 16.2 ± 2.1 | 16.4 ± 3.2 | p = 0.70 |

| LSPV (mm) | 17.2 ± 2.4 | 17.1 ± 2.5 | 16.9 ± 2.2 | p = 0.63 |

| LIPV (mm) | 14.4 ± 2.2 | 14.3 ± 1.7 | 14.3 ± 2.4 | p = 0.90 |

| Dimensions of the left atrium | ||||

| Transverse diameter (mm) | 61.1 ± 7.4 | 58.9 ± 7.7 | 62.5 ± 6.6 | p = 0.02 |

| Anteroposterior diameter (mm) | 48.4 ± 5.9 | 47.7 ± 5 | 48.5 ± 6.8 | p = 0.51 |

| Longitudinal diameter (mm) | 49 ± 6.9 | 47.2 ± 6.5 | 50.6 ± 7.4 | p = 0.02 |

| Volume (cm3) | 77.5 ± 23.7 | 71.1 ± 23.2 | 81.4 ± 23 | p = 0.03 |

AF: atrial fibrillation; BMI: body mass index; DM: diabetes mellitus; LIPV: left inferior pulmonary vein; LSPV: left superior pulmonary vein; OSAS: obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome; RIPV: right inferior pulmonary vein; RSPV; right superior pulmonary vein.

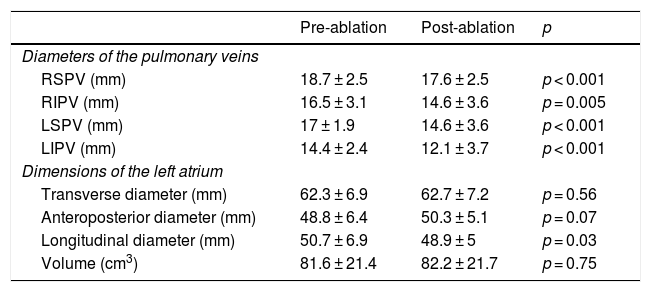

Clinical course monitoring following the ablation procedure demonstrated a slight decrease in the diameters of the pulmonary veins and in the longitudinal diameter of the left atrium. Left atrial volume did not undergo any significant changes (82.2 ± 21.7 cm3 versus 81.6 ± 21.4 cm3; p = 0.75; 95% CI: −44.8, 32.7) (Table 4).

Differences in the diameters of the pulmonary veins and diameters and volume of the left atrium following ablation.

| Pre-ablation | Post-ablation | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diameters of the pulmonary veins | |||

| RSPV (mm) | 18.7 ± 2.5 | 17.6 ± 2.5 | p < 0.001 |

| RIPV (mm) | 16.5 ± 3.1 | 14.6 ± 3.6 | p = 0.005 |

| LSPV (mm) | 17 ± 1.9 | 14.6 ± 3.6 | p < 0.001 |

| LIPV (mm) | 14.4 ± 2.4 | 12.1 ± 3.7 | p < 0.001 |

| Dimensions of the left atrium | |||

| Transverse diameter (mm) | 62.3 ± 6.9 | 62.7 ± 7.2 | p = 0.56 |

| Anteroposterior diameter (mm) | 48.8 ± 6.4 | 50.3 ± 5.1 | p = 0.07 |

| Longitudinal diameter (mm) | 50.7 ± 6.9 | 48.9 ± 5 | p = 0.03 |

| Volume (cm3) | 81.6 ± 21.4 | 82.2 ± 21.7 | p = 0.75 |

LIPV: left inferior pulmonary vein; LSPV: left superior pulmonary vein; RIPV: right inferior pulmonary vein; RSPV: right superior pulmonary vein.

The most significant observations of this study were as follows: first, most patients with arrhythmia had normal pulmonary vein anatomy, with no differences between the sexes; second, patients with persistent AF presented slightly larger dimensions for the left pulmonary veins and left atrium compared to patients with paroxysmal AF; and third, patients who experienced recurrence following the ablation procedure had a larger left atrium.

A pre-ablation CT angiogram provides information on the number of pulmonary veins and their diameters, measures the dimensions of the left atrium, identifies thrombi in the atrial appendage, detects abnormalities in pulmonary venous drainage, determines the integrity of the interatrial septum and determines the location of the oesophagus. Hence, it has become an indispensable tool for successful ablation and prevention of complications.9 The anatomy and anatomical variants of the pulmonary veins found in our study (25%) were consistent with the published literature. Chen et al.10 reported a 28.5% rate of anatomical variants in patients with AF, where accessory veins (17%) were predominantly on the right side and a common draining trunk was most often on the left side (7.5%). As all anatomical variants are potentially arrhythmogenic, detection of anatomical variants is important for planning the ablation procedure, monitoring the technique and reducing the risk of complications. It has been reported that, due to its small size, the right accessory pulmonary vein may go unnoticed during the ablation process and prove a cause of recurrence.10 Regarding AF recurrence and its relationship to anatomical variants of the pulmonary veins, the scientific literature is inconsistent. While some studies have found that patients with anatomical variants are at higher risk of AF recurrence,3,11 other studies have not found this association.12,13 Our study found no anatomical differences between patients who responded and patients who experienced recurrence of their arrhythmia.

Knowing the size of the pulmonary veins is important for choosing the size of the catheter to perform ablation and minimise complications. It has also been reported that the size of the pulmonary veins may have prognostic implications. Although our study did not find significant differences between the two groups, some authors such as Shimamoto et al.2 have reported that the size of the pulmonary veins estimated by CT angiogram may be an independent risk factor for AF recurrence. These authors demonstrated that, in patients with paroxysmal AF, pulmonary vein ostia with a larger area were associated with a higher risk of recurrence. The discrepancy between our results and those reported by said working group may be due to the fact that the latter measured the area of the ostia instead of the diameters of the pulmonary veins, as in our study. Since the ostia of the pulmonary veins have an elliptical shape with a long axis in a vertical orientation, it is likely that measuring the area of the ostia is more accurate than measuring the diameters. Another study by Lambert et al.14 also reported that the area of the ostium of the LSPV was a factor in AF recurrence. These authors also identified the angle between the interatrial septum and the RSPV as a parameter with prognostic value. According to them, a narrower angle indicates a higher level of difficulty in achieving contact between the ablation catheter and the RSPV, meaning ablation could be less effective.

One of the most significant predictors of recurrence following ablation is left atrial volume.10,13 In our cohort, we found that subjects who responded to ablation had a significantly higher left atrial volume than those who experienced recurrence of their arrhythmia; this finding was similar to that reported by Ejima et al.15 These authors studied 80 patients with atrial tachyarrhythmia resistant to anti-arrhythmic treatment who underwent ablation. After a follow-up period of more than two years, 21% of patients experienced recurrence of their arrhythmia. When they compared the study variables, they found that left atrial volume was the sole predictor of recurrence both in patients who had undergone a single ablation and in patients who had undergone multiple ablations. According to Ejima et al., the values for left atrial volume that best identified the risk of recurrence were those exceeding 86 cm3 following an initial ablation and 92 cm3 following multiple ablations.15 Other authors have noted that left atrial volume seems to be predictive of recurrence in patients with persistent AF but not so predictive in patients with paroxysmal AF.16 In addition to dimensions and volume, some authors have noted the usefulness of classifying the atrium according to its geometry,1 describing left atrial sphericity as a significant predictor of AF recurrence.17

Our study had some limitations. It was conducted at a single hospital; hence, results at other centres may vary. CT angiograms were performed with ECG synchronisation in order to measure the parameters as accurately as possible and reliably rule out the presence of intra-atrial thrombi. This acquisition protocol involved relatively high doses of radiation. In this regard, a recent study noted that atrial thrombi can be ruled out with similar reliability if studies without ECG synchronisation are performed; these involve a lower radiation dose.18 Data were collected retrospectively from medical histories taken by the physician responsible for the patient. As AF may present as asymptomatic episodes that cannot be detected by the patient, the arrhythmia recurrence rate may have been underestimated. This study did not specifically study the morphology and size of the atrial appendage. The literature is inconsistent with regard to its value as a predictor of AF recurrence.19,20 Finally, although the sample size studied was similar to that of other studies, a larger number of patients would probably have yielded results better suited to extrapolation to the population with AF.

In conclusion, CT angiography is a technique that enables acquisition of a detailed map of the anatomy of the pulmonary veins and the left atrium prior to pulmonary vein ablation in patients with AF, and yields data with prognostic value. The study must be extended, a larger number of subjects must be enrolled and the results must be validated in a broader population in order to more precisely determine the clinical value of the parameters obtained by CT angiogram in patients with arrhythmias.

AuthorsStudy integrity: UMU, MC, IS and GB.

Study concept: UMU, PR, IGB and GB.

Study design:

Data acquisition: UMU, MC, IS and GB.

Data analysis and interpretation: UMU, MC and GB.

Statistical processing: UMU and GB.

Literature search: MC, IS, PR, IGB and GB.

Drafting of the study: UMU and GB.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: UMU, MC, IS, PR, IGB and GB.

Approval of the final version: UMU, MC, IS, PR, IGB and GB.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Martinez Urabayen U, Caballeros M, Soriano I, Ramos P, García Bolao I, Bastarrika G. Características anatómicas de la aurícula izquierda en sujetos sometidos a ablación por radiofrecuencia de fibrilación auricular. Radiología. 2021;63:391–399.