Endoscopic lung volume reduction (BLVR) has emerged as an evidence-based, minimally invasive therapeutic option for patients with severe pulmonary emphysema who remain highly symptomatic despite optimal medical therapy and pulmonary rehabilitation. This SEPAR Clinical Protocol provides an updated, comprehensive, and standardized framework for the evaluation, selection, treatment, and follow-up of candidates for BLVR in Spain. The document synthesizes current scientific evidence on the efficacy and safety of available bronchoscopic techniques – principally endobronchial valves (EBV), bronchoscopic thermal vapor ablation (BTVA), and coils – highlighting the superiority and robustness of evidence supporting EBV therapy. Randomized controlled trials consistently show clinically meaningful improvements in lung function, hyperinflation, dyspnea, exercise tolerance, and health-related quality of life, particularly in patients without collateral ventilation. The protocol details the structural and organizational requirements for high-complexity BLVR programs, emphasizing the need for multidisciplinary teams, advanced imaging, comprehensive functional testing, and specialized inpatient care. It establishes clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, stressing the importance of radiological fissure assessment, physiological thresholds (FEV1 15–45%, RV >175%, DLCO >20%), smoking cessation, and appropriate symptom burden. Procedural sections describe indications, technical aspects, device characteristics, periprocedural management, and complication handling for EBV and BTVA. Finally, structured follow-up recommendations outline clinical, functional, radiological, and endoscopic monitoring to detect complications, evaluate loss of treatment effect, and guide valve revision or removal when necessary.

La reducción endoscópica del volumen pulmonar (BLVR) se ha convertido en una opción terapéutica mínimamente invasiva y basada en la evidencia para pacientes con enfisema pulmonar grave que siguen presentando síntomas graves a pesar del tratamiento médico óptimo y la rehabilitación pulmonar. Este protocolo clínico de la SEPAR proporciona un marco actualizado, completo y estandarizado para la evaluación, selección, tratamiento y seguimiento de los candidatos a BLVR en España. El documento sintetiza la evidencia científica actual sobre la eficacia y la seguridad de las técnicas broncoscópicas disponibles, principalmente las válvulas endobronquiales (EBV), la ablación térmica broncoscópica con vapor (BTVA) y las espirales, destacando la superioridad y solidez de la evidencia que respalda el tratamiento con EBV. Los ensayos controlados aleatorios muestran de forma sistemática mejoras clínicamente significativas en la función pulmonar, la hiperinflación, la disnea, la tolerancia al ejercicio y la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud, especialmente en pacientes sin ventilación colateral. El protocolo detalla los requisitos estructurales y organizativos de los programas BLVR de alta complejidad, haciendo hincapié en la necesidad de contar con equipos multidisciplinares, técnicas avanzadas de imagen, pruebas funcionales exhaustivas y atención hospitalaria especializada. Establece criterios claros de inclusión y exclusión, subrayando la importancia de la evaluación radiológica de la fisura, los umbrales fisiológicos (FEV1 15-45%, RV>175%, DLCO>20%), el abandono del tabaco y la carga sintomática adecuada. Las secciones sobre procedimientos describen las indicaciones, los aspectos técnicos, las características de los dispositivos, el manejo perioperatorio y el tratamiento de las complicaciones para EBV y BTVA.

.

In recent years, bronchoscopic lung volume reduction (BLVR) has consolidated its role as an innovative therapeutic strategy in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with severe pulmonary emphysema. This procedure has demonstrated efficacy in improving lung function, exercise capacity, and quality of life in carefully selected patients. As clinical evidence has expanded and patient selection criteria have been refined, the use of BLVR has steadily increased in Spain, underscoring the need for a reference document that establishes the foundations for its standardized implementation in clinical practice.

The Spanish COPD Guidelines (GesEPOC) on non-pharmacological treatment included a specific section on lung volume reduction, acknowledging its role in the treatment of patients with severe emphysema.1 However, since GesEPOC is a comprehensive guideline for the overall management of COPD,2 this section provided limited detail regarding patient selection, specific procedures, and follow-up. The growing complexity of available endoscopic techniques, along with the need for clear and structured protocols, calls for a more specialized document to guide healthcare professionals involved in the management of COPD in the use of BLVR.

The heterogeneity of care provided to COPD patients with severe emphysema who are candidates for endoscopic treatments represents a major challenge in clinical practice. Currently, patient selection, procedural approaches, and post-intervention follow-up vary considerably among centres. Therefore, it is essential to establish standardized assessment and referral criteria, as well as to harmonize procedures to ensure the best possible outcomes and minimize risks.

In this context, the COPD and Interventional Pulmonology, Pulmonary Function, and Lung Transplantation areas of SEPAR have developed this document with the objective of providing a detailed, evidence-based guide for the implementation of BLVR in COPD and severe emphysema. The protocol addresses patient selection criteria, indications for the different available techniques, the necessary multidisciplinary approach, and recommendations for follow-up. In addition, it seeks to serve as a reference for professional training, the organization of specialized units, and informed clinical decision-making. By doing so, it aims to homogenize patient care and improve access to an innovative therapy that may significantly enhance prognosis and quality of life.

Scientific evidence on bronchoscopic lung volume reductionChronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a complex and heterogeneous condition caused by abnormalities of the airways (bronchitis, bronchiolitis) and/or alveoli (emphysema), leading to progressive airflow limitation, hyperinflation, and chronic respiratory symptoms. Dyspnea is the most frequent and disabling symptom. Although its origin is multifactorial, dynamic hyperinflation (DH) – resulting from loss of elastic recoil and increased end-expiratory lung volume – is considered the main pathophysiological mechanism.3

Despite optimization of both pharmacological (bronchodilators) and non-pharmacological (physical activity, rehabilitation, oxygen therapy, non-invasive ventilation) treatments, patients with extensive emphysema and DH experience disabling dyspnea, reduced exercise tolerance, and impaired health-related quality of life (HRQoL).4 BLVR has emerged as an alternative therapy for these patients, offering a safer and less invasive option than surgery or lung transplantation, although not without procedure-related mortality (1–5%).5 Among BLVR techniques, endobronchial valves (EBV), coils, and bronchoscopic thermal vapor ablation (BTVA) have garnered the greatest interest. Other techniques such as coils (RePneu®, initially PneumRx Inc.), the AeriSeal® polymeric bio-adhesive (Aeris Therapeutics Inc.), or the Exhale® airway bypass stents (Bronchus Technologies) have been discontinued due to lack of proven clinical benefit. Currently, only EBVs hold approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). BTVA does not have FDA approval at present but has received CE marking in Europe and approval from the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) in Australia.

Endobronchial valvesUnidirectional EBVs allow air to exit during exhalation while preventing inflow during inhalation. This reduces hyperinflation in the treated region, induces local atelectasis, and relieves the mechanical burden on respiration, thereby improving dyspnea, exercise capacity, and HRQoL.6 EBVs have been FDA-approved since 2018.

The Endobronchial Valve for Emphysema Palliation Trial (VENT) was the first multicentre international randomized controlled trial (RCT) to demonstrate the benefit of BLVR with EBVs. However, the observed effects did not reach the minimal clinically important difference compared to standard treatment.7 A subsequent post hoc analysis revealed clinically and functionally significant benefits in the subgroup of patients with complete fissures as assessed by computed tomography (CT) and complete lobar atelectasis after EBV treatment.8 Since then, five additional RCTs using Zephyr valves (PulmonX Corp., USA)9–13 (Table 1) and four using Spiration valves (IBVs; Olympus, USA)14–17 (Table 2) have been published.

Results of change after endoscopic lung volume reduction treatment with EBV valves.

| Study (year of publication) | N (months) | FEV1 (l) | RV (l) | 6 MWD (m) | SGRQ (points) | Reduction in volume of the target lobe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BeLieVeR-HIFi (2015) | 50 (3) | 0.18 | −0.50 | 29 | −8.7 | |

| STELVIO (2015) | 68 (6) | 0.16 | −0.87 | 60 | −17.4 | −1.37 |

| IMPACT (2016) | 93 (3) | 0.10 | −0.42 | 23 | −8.6 | −1.20 |

| TRANSFORM (2017) | 97 (6) | 0.14 | −0.66 | 36 | −7.2 | −1.09 |

| LIBERATE (2018) | 190 (12) | 0.10 | −0.49 | 13 | −7.6 | −1.14 |

| Mean (range) | 0.14 (0.10–0.18 | −50 (−0.87 to −0.42) | 29 (13–60) | −8.6 (−17.4 to −7.2) | −1.17 (−1.37 to −1.09) |

Abbreviations: EBV, endobronchial valve; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second; RV, residual volume; 6MWD, distance walked in 6min; SGRQ, St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire; l, litres; m, metres.

Results of the change after endoscopic lung volume reduction treatment with IBV valves.

| Study (year of publication) | N (months) | FEV1 (l) | RV (l) | 6 MWD (m) | SGRQ (points) | Reduction in volume of the target lobe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ninane V (2012) | 37 (3) | 0.09 | −0.21 | 7 | −4.3 | – |

| Wood DE (2007) | 277 (6) | 0.07 | −0.31 | −24.02 | 32.2%**** | −0.224 |

| Reach Trial (2018) | 63 (6) | 0.09 | −0.42 | 20.8 | −8.38 | −0.99 |

| EMPROVE (2019) | 113 (6/12) | 37.2%* | −50.5%** | 32.4%*** | 50.5%**** | – |

Abbreviations: EBV, endobronchial valve; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second; RV, residual volume; 6MWD, distance walked in 6min; SGRQ, St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire; l, litres; m, metres.

Despite methodological differences in study design, type of emphysema (heterogeneous vs. homogeneous), and fissure assessment, all RCTs employing Zephyr valves demonstrated improvements in lung function, exercise tolerance, and quality of life, with an acceptable safety profile (Table 1). The overall mean change in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) from baseline to endpoint was 0.14L (0.10–0.18L), residual volume (RV) decreased by −0.50L (−0.87L to −0.42L), the 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) increased by 29m (13–60m), and the St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) score improved by −8.6 points (−17.4 to −7.2).18

For Spiration valves, a meta-analysis including 629 patients from four clinical trials (Table 2) showed that, in patients without collateral ventilation, FEV1 improved by 0.12L, SGRQ decreased by 12.27 points, and RV was reduced by an average of 360ml.19 Two recent meta-analyses compared outcomes between both valve types, finding modest but consistent advantages favouring Zephyr valves: +0.03L in FEV1, +30m in 6MWD, and −1.17 points in SGRQ.20,21

The safety profile of EBV therapy is favourable, although pneumothorax is the most frequent complication, occurring in 4–34% of cases.22 Most pneumothoraces occur within the first 72h (>85%).9,10 Other possible complications include pneumonia, COPD exacerbations, or haemoptysis.20,22

The impact of BLVR on exacerbations and survival has been less thoroughly studied. Brock et al.,23 in a retrospective series of 129 patients, observed a significant reduction in exacerbations one year after EBV implantation, with the greatest benefit in patients who developed complete lobar atelectasis. Regarding survival, early retrospective studies with small cohorts consistently demonstrated greater survival in patients achieving complete lobar atelectasis after BLVR.24–26 More recently, a study involving 1471 patients, of whom 483 underwent BLVR (73% EBVs, 27% coils), showed significantly longer median survival in the treated group compared with non-BLVR patients (3133 days [95% CI 2777–3489] vs. 2503 days [95% CI 2281–2725]; p<0.001).27

In Spain, the approximate cost per patient ranges from €7500 to €15,000 depending on the number and type of valves implanted.

CoilsAlthough EBVs currently represent the most effective therapeutic option within BLVR, coils have been proposed as an alternative for patients with homogeneous emphysema and/or collateral ventilation and remain available in Spain. Endobronchial coils (PneumRx/BTG, Mountain View, CA, USA) are nitinol devices with shape memory. Once deployed bronchoscopically, they return to their preset shape, compressing the lung parenchyma, thereby reducing hyperinflation and improving diaphragmatic function. Coils are generally implanted bilaterally in two separate procedures spaced 4–8 weeks apart.28 A recent meta-analysis of 680 patients29 demonstrated improvements in FEV1 at 3 and 6 months, reductions in RV, and improvements in SGRQ at 3, 6, and 12 months, as well as significant increases in 6MWD. In a small cohort of 22 patients followed for three years, the benefits gradually regressed to baseline.30 Adverse events have been reported in more than half of patients,31 with pneumonia being the most frequent complication.

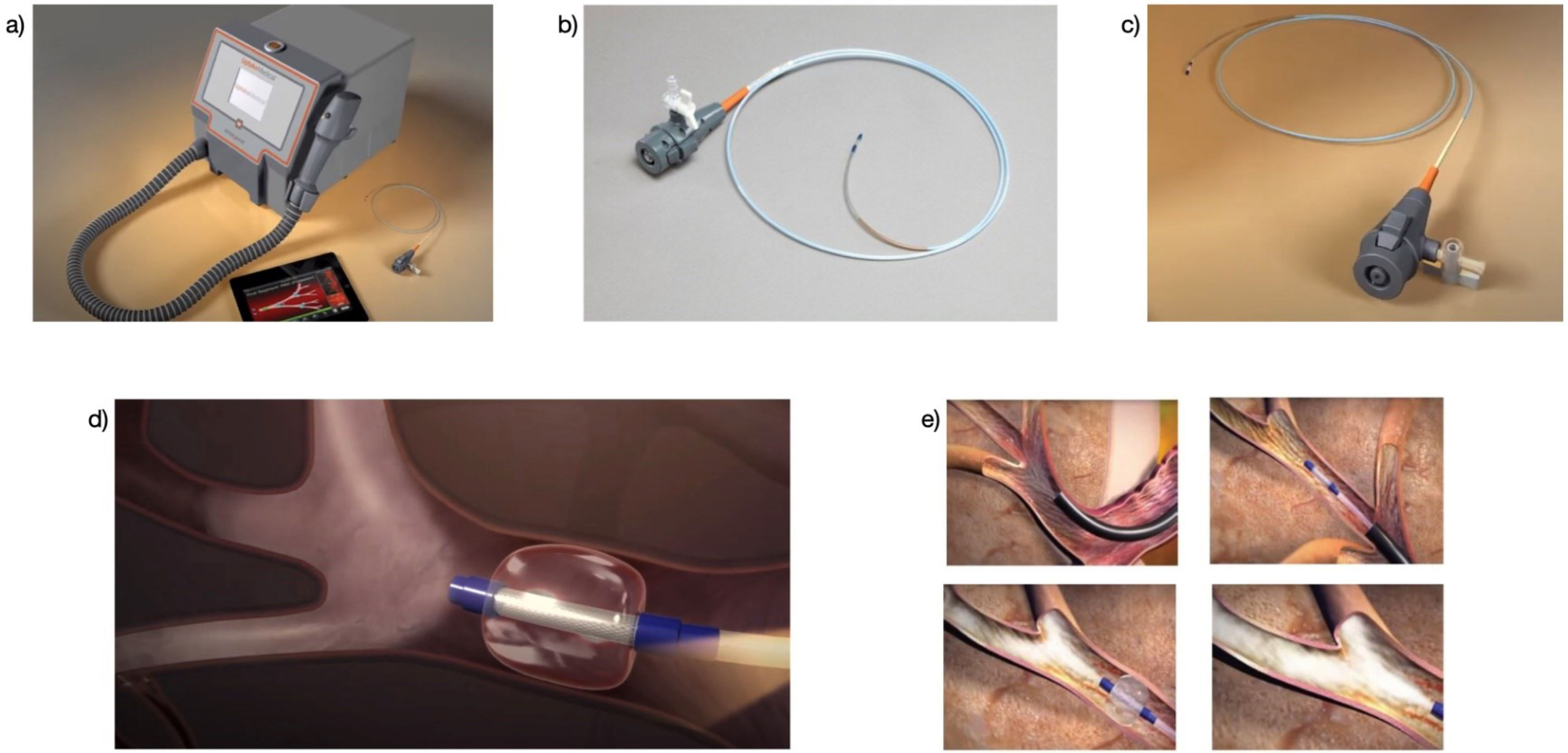

Bronchoscopic thermal vapor ablation (BTVA)The main limitation of EBVs is the presence of collateral ventilation due to incomplete fissures. In this context, BTVA has been shown to induce an inflammatory reaction followed by fibrotic remodelling and lung volume reduction. Initial lobar treatments were associated with frequent adverse events; however, limiting treatment to segmental areas and spacing sessions improved the safety profile. Nevertheless, BTVA has not yet been FDA-approved. A randomized controlled trial with six months’ follow-up demonstrated significant improvements in FEV1, reductions in SGRQ scores, and decreases in RV compared with controls.32 Subsequent observational studies have confirmed these findings.33,34 Although BTVA offers potential advantages over EBVs – such as segmental treatment and applicability in patients with incomplete fissures – safety concerns remain, and additional clinical trials are needed before broader implementation. The estimated cost per patient in Spain is €10,000–12,000 (two sessions, four segments).

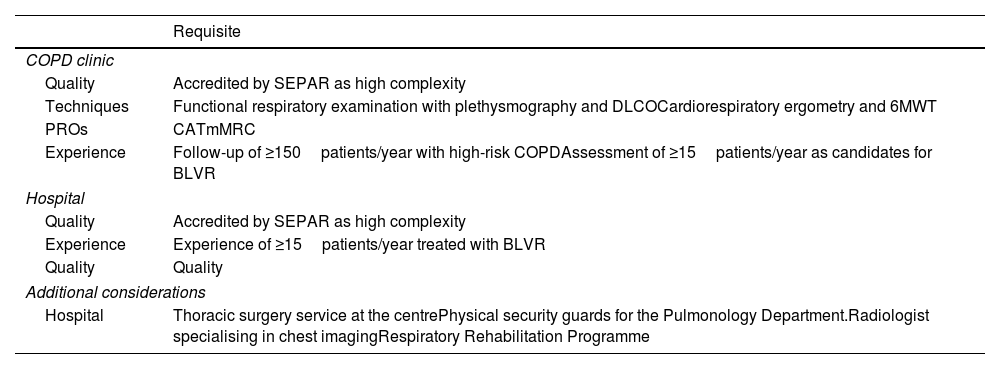

Requirements for a lung volume reduction programCOPD and Interventional Pulmonology Units performing BLVR procedures in patients with severe emphysema are recommended to be accredited by the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) as high-complexity units. This accreditation ensures compliance with the highest standards in infrastructure, equipment, staff training, and quality of care, ultimately translating into greater safety and efficacy of the procedures. However, the cornerstone of any BLVR program is the existence of a hospital-accredited multidisciplinary committee capable of evaluating each case individually and defining the most appropriate therapeutic strategy. This committee should include COPD specialists, interventional pulmonologists, thoracic surgeons, radiologists, and rehabilitation specialists. It should also oversee the implementation of a standardized registry of procedures to assess both efficacy and safety. Such a registry must include quality indicators such as success rates, complications, reinterventions, and functional outcomes. Regular audits and participation in continuing education programs are also recommended to ensure continuous quality improvement.

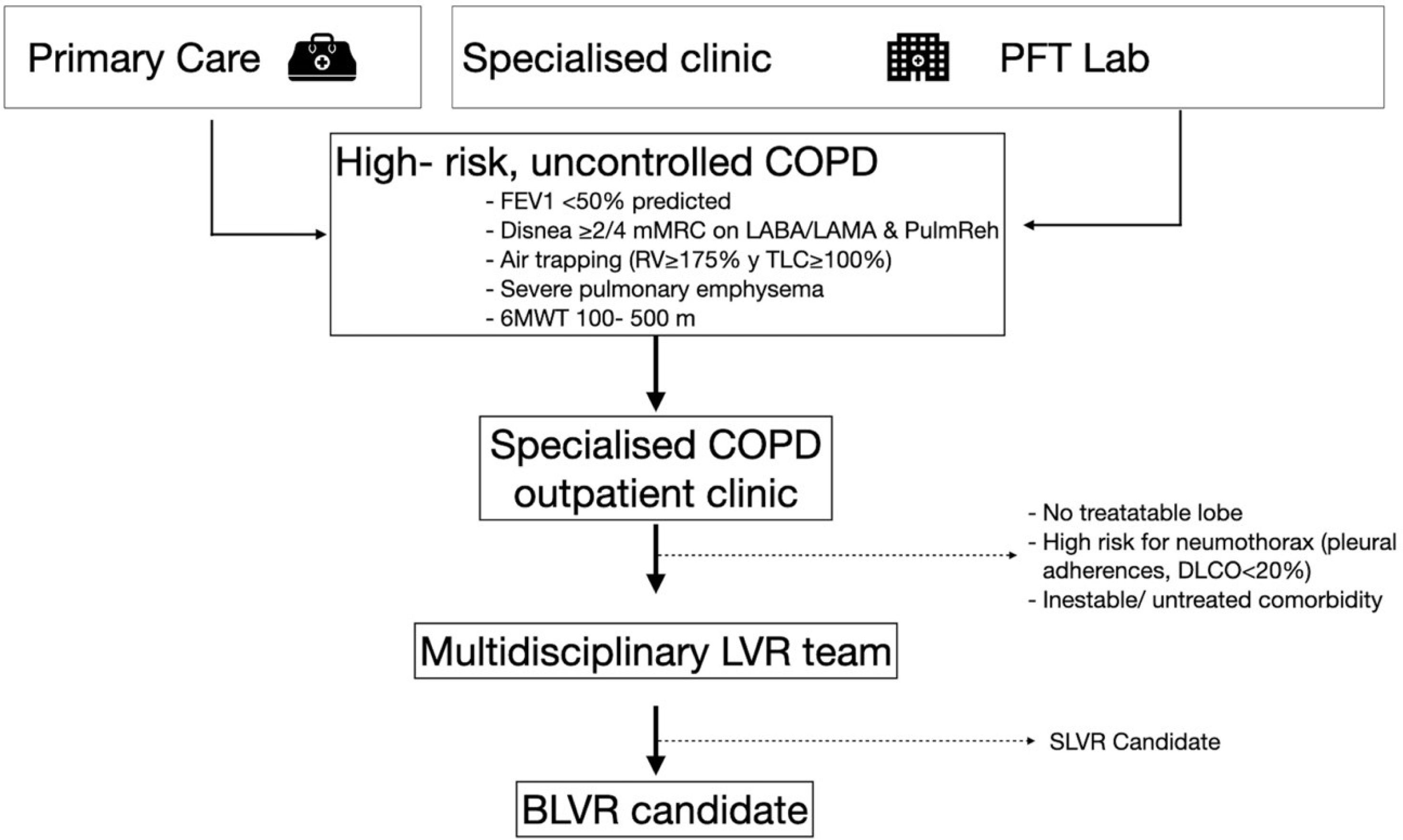

It is essential that these units be integrated into tertiary-level hospitals with the necessary infrastructure to provide comprehensive care for these patients. Most patients will be referred from specialized COPD outpatient clinics, which must have substantial experience managing high-risk COPD cases through a multidimensional assessment, including the routine use of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) such as the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) and the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scale. Without a high-complexity COPD clinic able to identify potential candidates, BLVR programs are unlikely to reach the minimum annual case volume required to ensure efficacy and safety35 (Fig. 1).

Process for assessing and selecting candidates for BLVR. LVR: lung volume reduction; SLVR: surgical lung volume reduction; FEV1: forced respiratory volume in the 1st second; mMRC: modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale; LABA: long acting beta-agonist; LAMA: long-acting muscarinic antagonist; PulmReh: pulmonary rehabilitation; RV: residual volume; TLC: total lung capacity; 6MWT: 6-minute walking test; LVR: lung volume reduction; SLVR: surgical lung volume reduction; BLVR: bronchoscopic lung volume reduction.

In addition, the program requires the availability of a specialized inpatient unit for pre- and post-procedure management, as well as immediate access to an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for the treatment of potential severe complications. Clear referral protocols must also be in place with other Pulmonology departments in the hospital's catchment area to ensure continuity of care when additional support is needed.

To perform BLVR, the unit must have a bronchoscopy suite equipped with the necessary technology for advanced procedures, including conventional and therapeutic videobronchoscopes, rigid bronchoscopy (desirable for complex valve removal or significant airway bleeding), and electrocautery/photocoagulation or electrocoagulation systems for resection of perivalvular granulomas that may hinder valve extraction, as well as a fluoroscopy unit.

Diagnostic support is also a critical component. Access to advanced imaging is required, such as high-resolution chest computed tomography with ventilation and perfusion analysis software for accurate patient selection. In centres lacking this technology, access to external software for emphysema quantification and fissure integrity assessment must be ensured. A well-equipped pulmonary function laboratory is also necessary, capable of performing spirometry, plethysmography, and diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) measurement. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing and the 6-minute walk test (6MWT) are also considered essential for evaluating functional capacity and optimizing intervention outcomes.

The multidisciplinary team within these units must be highly trained and experienced in the management of advanced COPD and endoscopic procedures. Specifically, the presence of pulmonologists with expertise in Interventional Pulmonology and formal training in BLVR techniques is indispensable. Based on expert opinion, each interventionalist should perform at least 15–20 BLVR procedures annually.36

Additional key team members include thoracic radiologists with advanced imaging expertise, thoracic surgeons for surgical management of complications, anaesthesiologists experienced in treating patients with severe COPD, specialized nursing staff in bronchoscopy and advanced respiratory care, and respiratory physiotherapists who play a critical role in pre- and post-procedure functional optimization (Table 3).

Requirements for BLVR centres.

| Requisite | |

|---|---|

| COPD clinic | |

| Quality | Accredited by SEPAR as high complexity |

| Techniques | Functional respiratory examination with plethysmography and DLCOCardiorespiratory ergometry and 6MWT |

| PROs | CATmMRC |

| Experience | Follow-up of ≥150patients/year with high-risk COPDAssessment of ≥15patients/year as candidates for BLVR |

| Hospital | |

| Quality | Accredited by SEPAR as high complexity |

| Experience | Experience of ≥15patients/year treated with BLVR |

| Quality | Quality |

| Additional considerations | |

| Hospital | Thoracic surgery service at the centrePhysical security guards for the Pulmonology Department.Radiologist specialising in chest imagingRespiratory Rehabilitation Programme |

DLCO: carbon monoxide diffusion; 6MWT: 6-minute walk test; CAT: COPD Assessment Test; mMRC: modified Medical Research Council dyspnoea scale; PROs: patient-reported outcomes; BLVR: endoscopic lung volume reduction.

Several bronchoscopic techniques are currently available for the treatment of air trapping in emphysema, all aimed at improving lung function, reducing hyperinflated lung volume, and thereby enhancing ventilatory capacity, dyspnea, exercise tolerance, and overall quality of life. It is important to highlight that these procedures are not without risks, and complications may arise. Each technique has specific indications as well as contraindications or limitations that must be carefully considered.

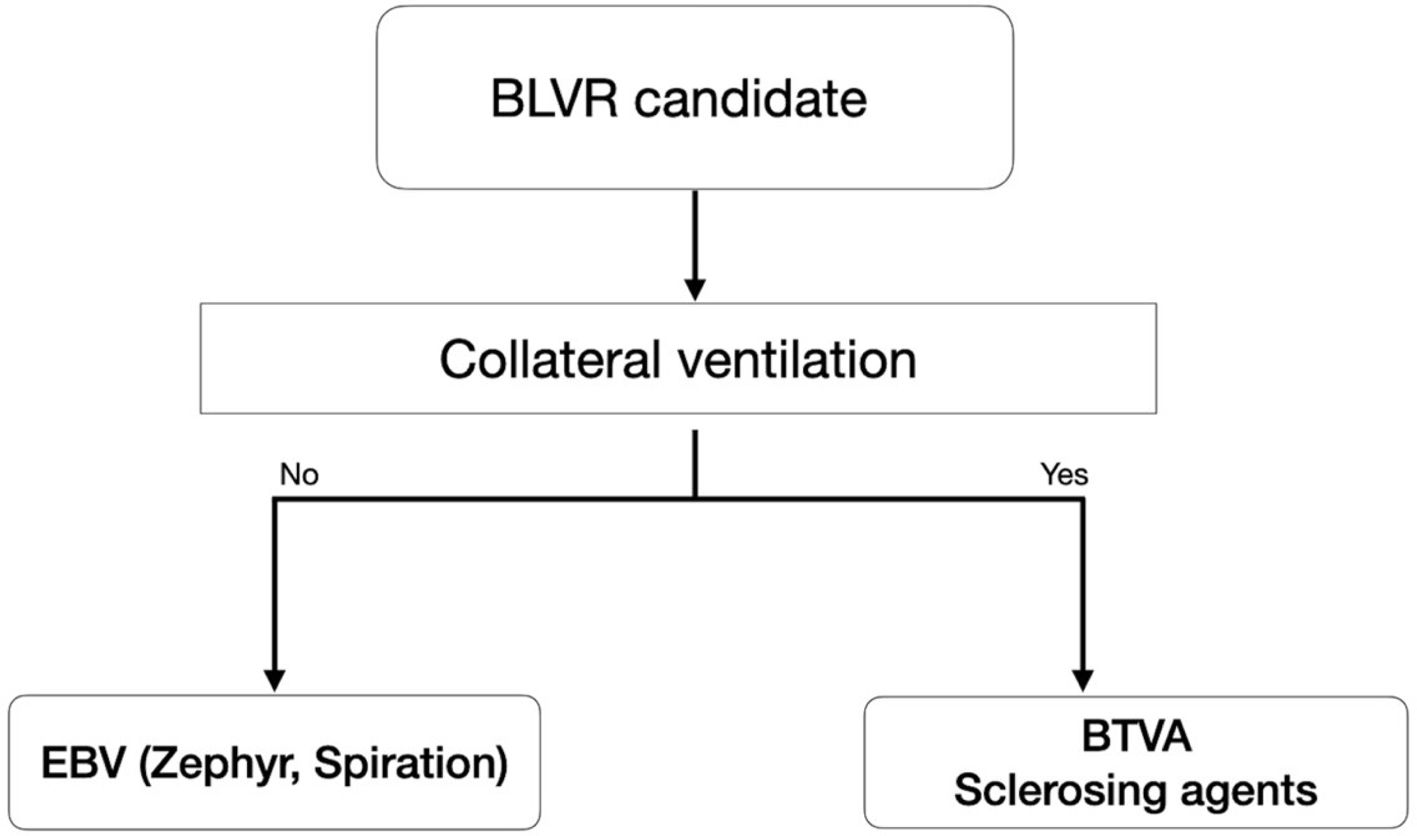

Among the different available techniques, endobronchial valve (EBV) placement has the broadest dissemination and strongest level of evidence. Other options, such as bronchoscopic thermal vapor ablation (BTVA) or the instillation of sclerosing agents to induce atelectasis, may serve as alternatives, particularly in patients with incomplete fissures and collateral ventilation. Therefore, the choice of procedure depends mainly on the type of emphysema and the presence or absence of collateral ventilation. Importantly, EBVs can be removed, making them a reversible treatment, whereas the other approaches are not.

In any case, careful patient selection is critical for procedural success, especially considering the high cost of these interventions. Below are the principal criteria that should be met when considering bronchoscopic lung volume reduction in patients with COPD and severe emphysema who remain highly symptomatic despite optimal medical therapy and completion of a pulmonary rehabilitation program:

- -

Age between 40 and 75 years (older patients may be considered if no other contraindications exist).

- -

A minimum of 4 months of smoking abstinence, confirmed by carbon monoxide levels in exhaled air or blood. Smoking cessation is essential, as active smokers face higher complication risks and therapeutic futility.

- -

Confirmed diagnosis of severe emphysema by high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT), including assessment of emphysema distribution, degree of heterogeneity, and anatomical location. Specialized software should then be used to determine fissure integrity, which will guide the choice of procedure.

- -

Pulmonary function tests: post-bronchodilator FEV1 between 15 and 45% predicted; total lung capacity (TLC) >100% predicted; residual volume (RV) >175% predicted. Regarding diffusing capacity (DLCO), studies have used an inclusion threshold of DLCO >20% predicted normal (7,13).

- -

Dyspnea score ≥2/4 on the mMRC scale (unable to keep pace with peers of the same age), despite optimized medical treatment and rehabilitation. The primary therapeutic goal of BLVR is to alleviate dyspnea and thus improve quality of life.

- -

6-minute walk test (6MWT): Patients should be able to walk between 100 and 500m. This reflects both disease severity and candidacy, as uncontrolled symptoms are the principal indication for BLVR.

- -

In selected cases with clinical uncertainty, a ventilation/perfusion scan may aid in decision-making.37

- -

For EBV placement, once a patient meets the above criteria, the presence and degree of collateral ventilation must be assessed (Fig. 2). This is typically performed using the Chartis® Pulmonary Assessment System. By contrast, vapor ablation or sclerosing agents are unaffected by collateral ventilation and may be alternatives for such patients.

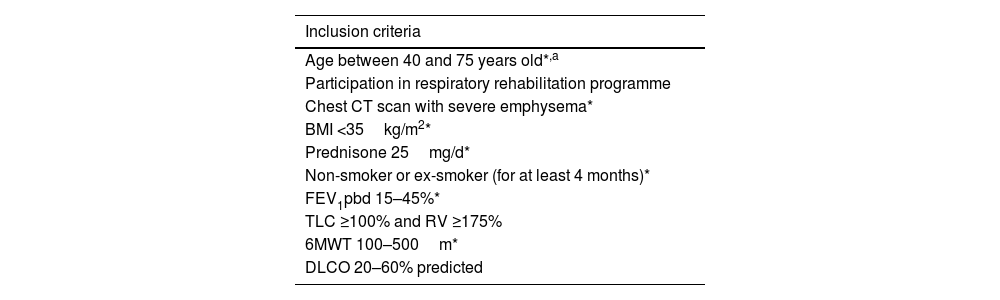

Table 4 summarizes the inclusion criteria that should be met before proceeding with BLVR. Likewise, Table 5 lists the contraindications that should preclude the intervention.

Inclusion criteria for an endoscopic volume reduction technique.

| Inclusion criteria |

|---|

| Age between 40 and 75 years old*,a |

| Participation in respiratory rehabilitation programme |

| Chest CT scan with severe emphysema* |

| BMI <35kg/m2* |

| Prednisone 25mg/d* |

| Non-smoker or ex-smoker (for at least 4 months)* |

| FEV1pbd 15–45%* |

| TLC ≥100% and RV ≥175% |

| 6MWT 100–500m* |

| DLCO 20–60% predicted |

CT: computed tomography, BMI: body mass index, FEV1pbd: post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in one second, TLC: total lung capacity, RV: residual volume, 6MWT: 6-minute walk test, DLCO: carbon monoxide diffusion capacity.

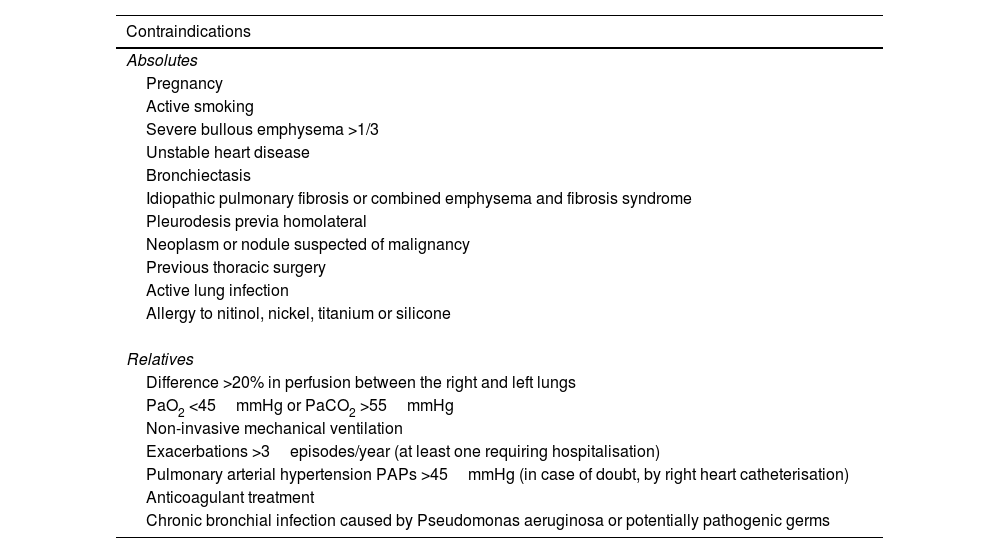

Exclusion criteria for an endoscopic volume reduction technique.

| Contraindications |

|---|

| Absolutes |

| Pregnancy |

| Active smoking |

| Severe bullous emphysema >1/3 |

| Unstable heart disease |

| Bronchiectasis |

| Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis or combined emphysema and fibrosis syndrome |

| Pleurodesis previa homolateral |

| Neoplasm or nodule suspected of malignancy |

| Previous thoracic surgery |

| Active lung infection |

| Allergy to nitinol, nickel, titanium or silicone |

| Relatives |

| Difference >20% in perfusion between the right and left lungs |

| PaO2 <45mmHg or PaCO2 >55mmHg |

| Non-invasive mechanical ventilation |

| Exacerbations >3episodes/year (at least one requiring hospitalisation) |

| Pulmonary arterial hypertension PAPs >45mmHg (in case of doubt, by right heart catheterisation) |

| Anticoagulant treatment |

| Chronic bronchial infection caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa or potentially pathogenic germs |

PAPs: pulmonary arterial systolic pressure, PaO2: partial pressure of oxygen, PaCO2: partial pressure of carbon dioxide.

Because these procedures are complex and costly, they are only performed in a limited number of centres. Therefore, if a given hospital does not offer BLVR, patients should be referred to a reference centre once deemed appropriate, ideally after undergoing the maximum number of recommended tests available locally and, whenever possible, after specialist assessment by their referring pulmonologist.

ProcedureAt present, the two bronchoscopic techniques most commonly performed in Spain are endobronchial valves (EBV) and bronchoscopic thermal vapor ablation (BTVA).

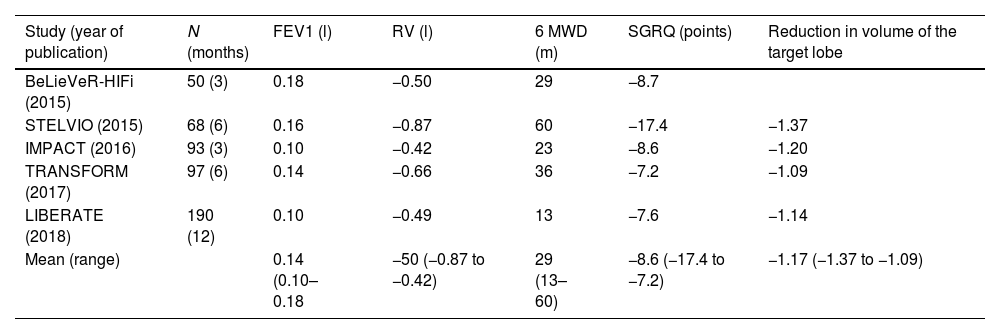

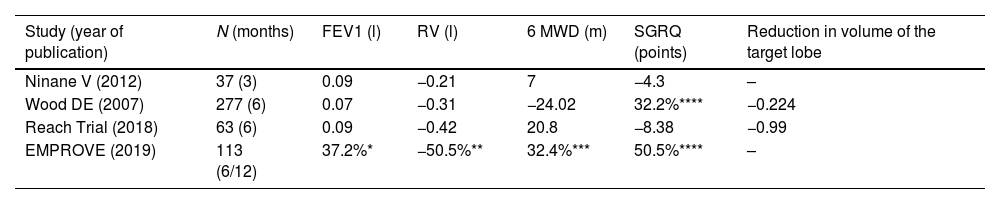

Endobronchial valvesUnidirectional EBVs are designed to exclude the most diseased pulmonary lobe. Valves are implanted to occlude all segmental bronchi of the target lobe, producing atelectasis that reduces hyperinflation and relieves the load on respiratory muscles. EBVs are used in both heterogeneous and homogeneous emphysema, as well as in upper and lower lobes. Treatment is unilateral, and the target lobe must be carefully selected. For this purpose, radiological assessment is performed (using SeleCT software from Olympus or StratX from Pulmonx, depending on the chosen valve type) to quantify emphysema severity, heterogeneity, and fissure integrity. Two valve types are available: Spiration (Olympus) and Zephyr (Pulmonx).

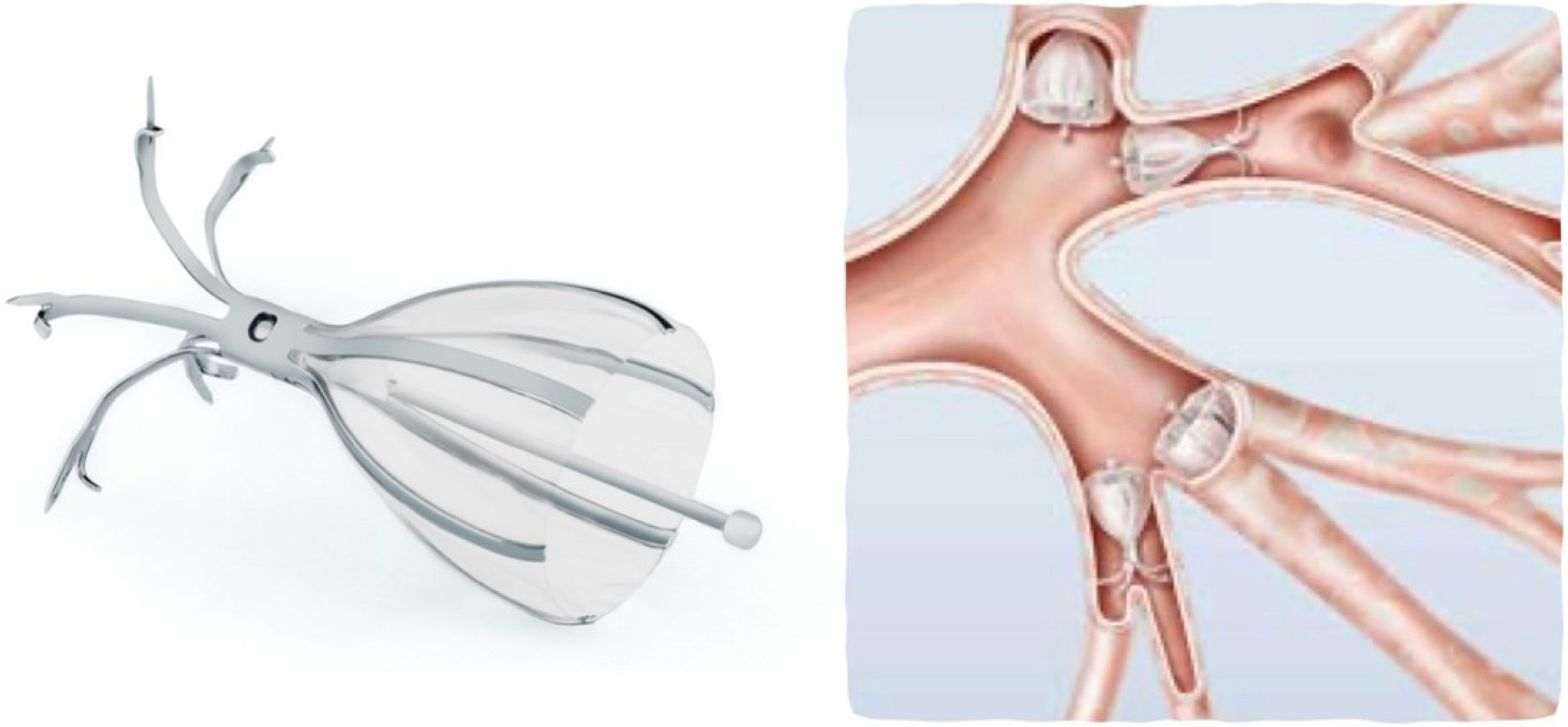

Spiration® valveThe Spiration valve is a self-expanding umbrella-shaped device, deployed through a catheter passed via a therapeutic flexible bronchoscope. It has FDA approval for persistent air leaks and, in Europe, for emphysema treatment as well. The valve limits airflow into the target airway while allowing exhalation and secretion clearance along its outer surface17 (Fig. 4).

It consists of a nitinol framework coated with silicone. Distally, five metallic anchors fix the valve in place, while proximally, six struts secure the membrane against the bronchial wall. The device compresses and expands with respiration, ensuring unidirectional airflow. A central rod facilitates grasping with forceps for removal if required. Valves are available in diameters of 5, 6, 7, and 9mm. Sizing is determined using a balloon catheter calibrated with saline solution; the required inflation volume estimates the appropriate valve size. The valve is then loaded into the delivery catheter, which has a marker to align with the bronchial edge for accurate deployment.

Although various studies have evaluated this device, evidence of its clinical benefit remains limited.15,17 A frequent complication is long-term granuloma formation associated with metallic anchors, as the valves are designed for permanent implantation.

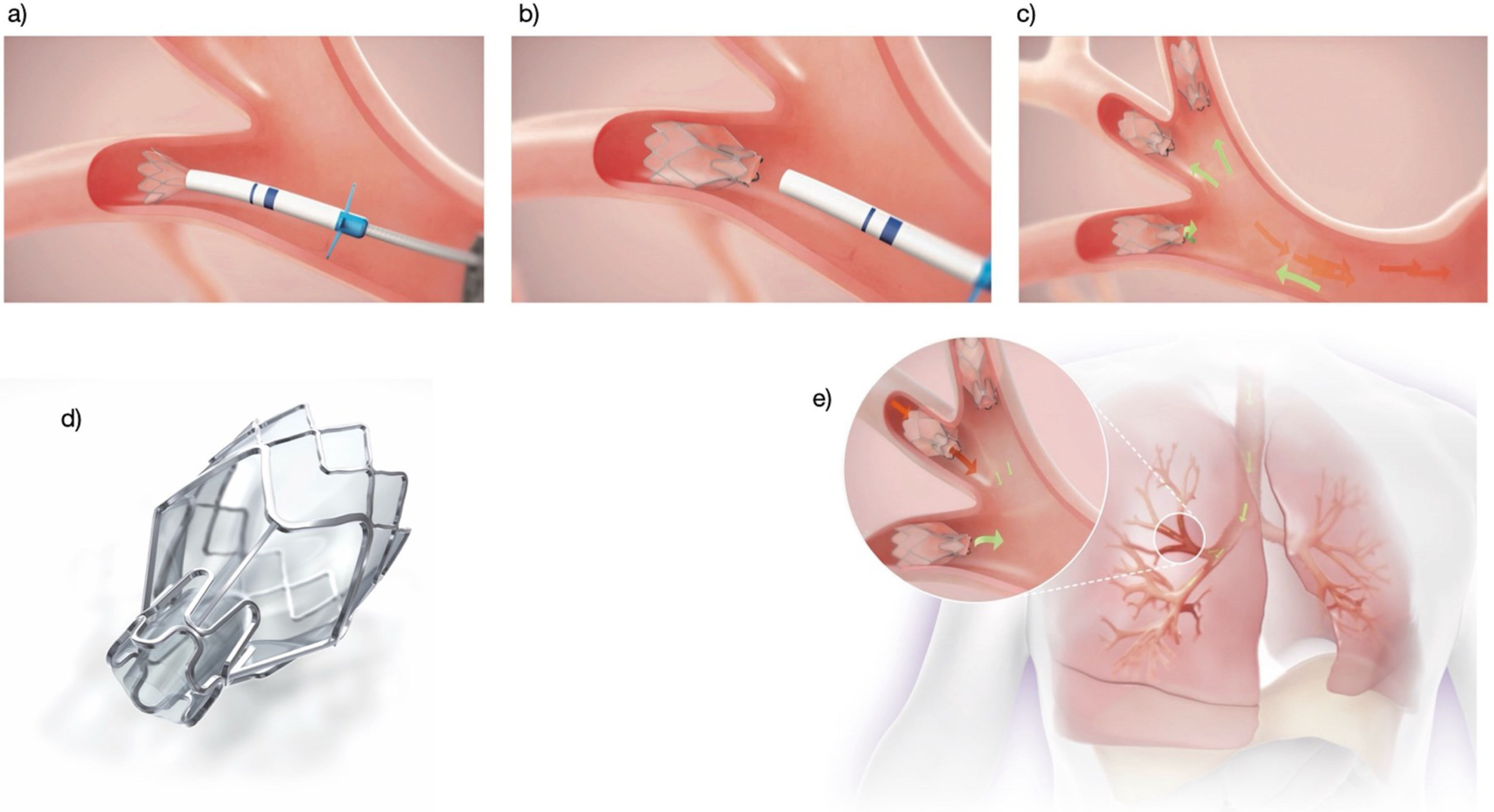

Zephyr® valveThe Zephyr valve is a self-expanding nitinol device covered with silicone, resembling a self-expanding stent. At its centre, a unidirectional valve allows airflow during exhalation while preventing inspiration. It is introduced folded into a catheter via a therapeutic bronchoscope. Two catheter sizes are available, which also serve for airway measurement, featuring cross-shaped extensions (5.5mm and 8.5mm) at the distal tip. A marker indicates the valve's length, which must align with the bronchial margin. Once in place, the valve is deployed to occlude the segmental bronchus.

Valves are available in 4mm and 5.5mm diameters, each in standard or long formats depending on bronchial depth. As there is no exposed metal, granuloma formation is less likely, though it can occur, particularly if valves are placed too deep. The valve closes during inspiration and opens during expiration, allowing secretion drainage and lobar deflation.

When fissure integrity is uncertain, the Chartis® Pulmonary Assessment System can be used. A balloon occludes the target lobe, and exhaled airflow is monitored: a gradual decrease indicates absence of collateral ventilation, while persistent flow beyond 5min suggests significant collateral ventilation.

The Zephyr valve has the strongest supporting evidence and is by far the most frequently used device for BLVR in Spain.13,28

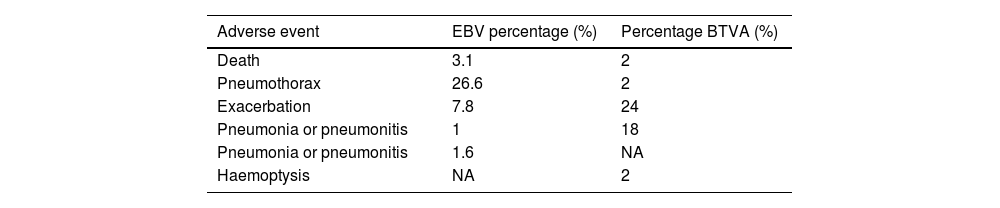

Valve placement can be performed under conscious sedation or general anaesthesia with endotracheal intubation, the latter preferred to suppress coughing. Preventive antibiotic therapy (5–7 days) should begin one day prior to implantation, covering common respiratory pathogens (H. influenzae, S. pneumoniae, M. catarrhalis) (Fig. 3). Given the risk of complications, especially pneumothorax, hospitalization for at least 24–48h is recommended. Chest radiography or thoracic ultrasound should be performed within the first 24h and at discharge to detect complications.38,39 Adverse events are summarized in Table 6. Procedure-related mortality ranges from 1% to 5% depending on series.

Adverse effects of bronchoscopic volume reduction with EBV and BTVA.

| Adverse event | EBV percentage (%) | Percentage BTVA (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Death | 3.1 | 2 |

| Pneumothorax | 26.6 | 2 |

| Exacerbation | 7.8 | 24 |

| Pneumonia or pneumonitis | 1 | 18 |

| Pneumonia or pneumonitis | 1.6 | NA |

| Haemoptysis | NA | 2 |

EBV: endobronchial valves, BTVA: bronchial thermal vapor ablation.

Modified from quote 10 and 30. NA: not available.

BTVA is approved in the European Union for lung volume reduction in heterogeneous emphysema predominantly affecting the upper lobes. The treatment is segmental rather than lobar, allowing sequential bilateral application, with at least 3 months between procedures.32 HRCT with company-provided software is used to quantify emphysema severity, heterogeneity, segmental volume, and identify treatable segments. The software also calculates per-segment volume, tissue mass, energy required (calories/g), and application time. During the procedure, a catheter with a distal balloon (passed through a therapeutic bronchoscope) seals the segment to be treated. Sterile water vapor at ∼70°C is then applied, inducing an inflammatory reaction followed by fibrosis and atelectasis. The maximum volume per procedure is limited to 1700cm3 to avoid excessive inflammation. Up to two segments of a lobe can be treated per session (Fig. 5).

Antibiotic prophylaxis is similar to that used for EBVs. There is ongoing debate regarding the use of oral corticosteroids to prevent post-procedure complications, versus reserving them for cases of exacerbation. Pneumothorax is rare following BTVA, but COPD exacerbations, pneumonitis (sometimes difficult to differentiate from pneumonia), and mild haemoptysis are relatively frequent. Aggressive inpatient management is required for exacerbations. Post-procedure hospitalization for at least 48–72h is recommended.

Adverse events are summarized in Table 6. They are most common during the first 3 months, particularly in the first month. Procedure-related mortality ranges from 1% to 5% across series.

Monitoring and evaluation of the therapeutic responseEndoscopic lung volume reduction treatment in severe emphysema offers benefits in lung function, exercise capacity, and quality of life.9,40–43 However, long-term outcomes remain less well understood.44 In the study by Hartman et al.45 and the German register by Gompelmann et al.46 significant improvements were observed at 3 years in lung function, dyspnoea and quality of life; also in exercise capacity at 2 years with BLVR using EBV, with a gradual decrease over time in the changes achieved.

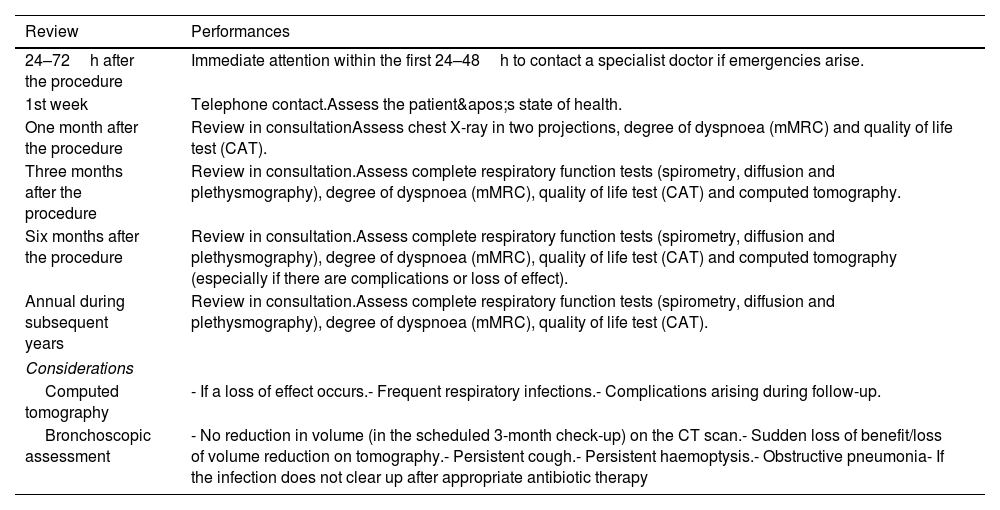

Close, standardised monitoring is important to optimise treatment outcomes, assess its effect or loss of effect, and detect the onset of complications. Some complications can be treated by your regular pulmonologist; however, specific problems arising from endoscopic procedures (VEB) valves will require assessment by a unit with more specific experience in BLVR. A panel of experts in 2017,28 established a document as a guideline to perform follow-up at one month, three months, six months, and annually after the procedure to closely monitor all the benefits obtained and possible complications. Table 7 describes the actions to be taken in the follow-up of patients treated with BLVR.

Clinical, radiological and endoscopic follow-up.

| Review | Performances |

|---|---|

| 24–72h after the procedure | Immediate attention within the first 24–48h to contact a specialist doctor if emergencies arise. |

| 1st week | Telephone contact.Assess the patient's state of health. |

| One month after the procedure | Review in consultationAssess chest X-ray in two projections, degree of dyspnoea (mMRC) and quality of life test (CAT). |

| Three months after the procedure | Review in consultation.Assess complete respiratory function tests (spirometry, diffusion and plethysmography), degree of dyspnoea (mMRC), quality of life test (CAT) and computed tomography. |

| Six months after the procedure | Review in consultation.Assess complete respiratory function tests (spirometry, diffusion and plethysmography), degree of dyspnoea (mMRC), quality of life test (CAT) and computed tomography (especially if there are complications or loss of effect). |

| Annual during subsequent years | Review in consultation.Assess complete respiratory function tests (spirometry, diffusion and plethysmography), degree of dyspnoea (mMRC), quality of life test (CAT). |

| Considerations | |

| Computed tomography | - If a loss of effect occurs.- Frequent respiratory infections.- Complications arising during follow-up. |

| Bronchoscopic assessment | - No reduction in volume (in the scheduled 3-month check-up) on the CT scan.- Sudden loss of benefit/loss of volume reduction on tomography.- Persistent cough.- Persistent haemoptysis.- Obstructive pneumonia- If the infection does not clear up after appropriate antibiotic therapy |

mMRC: modified Medical Research Council dyspnoea scale; CAT: COPD Assessment Test.

Follow-up bronchoscopy is recommended in clinical practice for patients who show no clinical response or experience a sudden late loss of benefit, based on lung function tests and follow-up computed tomography (absence, minimal or loss of atelectasis of the treated lobe).47. It is therefore advisable to perform a bronchoscopy in the following situations: (1) no volume reduction is achieved approximately 12 weeks after treatment; (2) sudden loss of treatment benefit and/or loss of volume reduction; (3) presence of persistent cough, persistent haemoptysis or obstructive pneumonia.13,44,48

During the additional bronchoscopic evaluation, the valves are inspected and, if necessary, cleaned, adjusted, replaced, or removed.28,49 The reasons for permanent valve removal are unsatisfactory treatment outcome, severe granulation tissue formation, severe haemoptysis (caused by granulation tissue), hypoxaemia, and obstructive pneumonia. The most common diagnosis during follow-up bronchoscopies, found in 53% of patients, was granulation tissue formation causing valve dysfunction, as well as haemoptysis and persistent cough.8,50,51 The most common procedure performed was valve replacement and, in some cases, permanent valve removal. The main reason for permanent removal was unsatisfactory treatment outcome for which no other intervention was considered possible three months after the procedure, as well as persistent air leakage after chest tube placement for pneumothorax. If the valves were retained, follow-up bronchoscopy improved the effect of treatment, according to the results of pulmonary function testing, in patients who had previously experienced no effect from treatment or a loss of its initial effect. Sometimes, this may not be due to direct interaction of the valve with the target bronchus itself, but rather to interaction of the valve casing with the adjacent bronchial wall or if an edge of an eccentrically placed valve scrapes the mucosa during coughing. In rare cases, airway remodelling or bronchial torsion has been observed. A tightly fitted valve may leak if the bronchus changes shape elliptically. It is recommended to replace the valve in such a situation.

The formation of granulation tissue is one of the therapeutic challenges of treatment following VEB implantation and in all interventional bronchoscopic procedures involving implantable devices in the lung, such as stents. Not much is known about the aetiopathogenesis or what risk factors are associated with the development of granulation tissue.51 Most patients with granulation tissue formation will experience a loss of the initial effect of the treatment, and valve replacement will be necessary.47 Treatment consists of removing the valve and, if necessary, treating the granulation tissue by cryoablation with a cryoprobe, if available. In the first case, it is recommended to replace the valve with a larger one 6 weeks later, assuming that the granulation tissue has disappeared. In the case of temporary removal, a “cooling-off” period of approximately 12 weeks is advisable before performing a follow-up review bronchoscopy with the intention of replacing the valves. Care should be taken to place the valve as centrally as possible to avoid irritation of the wall.

Computed tomography will be performed if there is a loss of benefit or complications or frequent respiratory infections appear. If no changes are observed on the CT scan, we will first evaluate your history of exacerbations to determine whether they are justified by the disease or due to endoscopic volume reduction. If it is the natural course of the disease, the doses of inhaled bronchodilators and other therapies will be increased as described in the GOLD/GesEPOC guidelines.2 Long-term infection is rare, and the recommendation is to follow the standard 7- to 14-day course of oral antibiotics. If the infection does not clear up after appropriate antibiotic therapy, removal of the valves and a second course of antibiotic therapy will be considered. Table 8 summarises the main considerations in the follow-up of patients treated with endoscopic volume reduction.

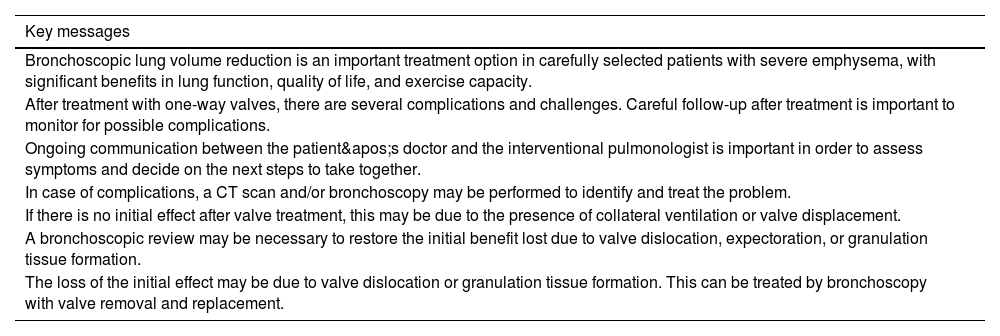

Key messages for follow up.

| Key messages |

|---|

| Bronchoscopic lung volume reduction is an important treatment option in carefully selected patients with severe emphysema, with significant benefits in lung function, quality of life, and exercise capacity. |

| After treatment with one-way valves, there are several complications and challenges. Careful follow-up after treatment is important to monitor for possible complications. |

| Ongoing communication between the patient's doctor and the interventional pulmonologist is important in order to assess symptoms and decide on the next steps to take together. |

| In case of complications, a CT scan and/or bronchoscopy may be performed to identify and treat the problem. |

| If there is no initial effect after valve treatment, this may be due to the presence of collateral ventilation or valve displacement. |

| A bronchoscopic review may be necessary to restore the initial benefit lost due to valve dislocation, expectoration, or granulation tissue formation. |

| The loss of the initial effect may be due to valve dislocation or granulation tissue formation. This can be treated by bronchoscopy with valve removal and replacement. |

This clinical protocol is based exclusively on the synthesis of published scientific evidence and expert consensus. It does not involve the collection of new patient data, experimental interventions, or procedures carried out specifically for the development of this document. Accordingly, no ethical concerns beyond those inherent to routine clinical practice are identified. Nevertheless, the protocol strongly recommends that all bronchoscopic lung volume reduction (BLVR) procedures be performed in accredited high-complexity centres and follow national and international ethical standards for patient safety, autonomy, and beneficence.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processArtificial intelligence tools were used exclusively to support editing and linguistic refinement of the manuscript. AI tools did not influence the scientific content, data interpretation, or clinical recommendations, which are based solely on expert consensus and published evidence. All final decisions regarding content were made by the authors.

Informed consentThis protocol does not include original research involving human subjects and therefore does not require informed consent. However, it emphasizes that all patients undergoing BLVR must provide written informed consent as part of standard clinical care, after being fully informed of the indications, expected benefits, potential risks, alternative treatment options, and specific device-related considerations.

FundingNo external funding was received for the development, writing, or review of this SEPAR clinical protocol. All contributing experts participated voluntarily as part of the scientific mission of the society.

Authors’ contributionsAll listed authors contributed substantially to the conception, drafting, and critical revision of the protocol. They approved the final version and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. The authorship structure adheres to the ICMJE recommendations for scholarly contributions.

Conflicts of interestB.A.N. has received consultancy fees, research grants, or lecture honoraria from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, CSL Behring, GSK, Laboratorios Bial, Laboratorios Menarini, and Sanofi.

M.J.B.B. has received lecture honoraria from Medtronic, Faes Farma, AstraZeneca, Chiesi, Olympus, Ambu, and Pulmonx.

A.C.V. has received lecture honoraria from Pulmonx.

M.C.R. has received lecture honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bial, Chiesi, CSL Behring, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, Grifols, and Pulmonx, and consultancy honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols, and Bial.

E.C.V. has received lecture honoraria from Olympus and Pulmonx.

J.M.D. has received research grants, lecture or consultancy honoraria, or travel support from AstraZeneca, BIAL, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Faes, Ferrer, Gebro, Grifols, GSK, Janssen, Menarini, Mundipharma, Novartis, Sanofi, Roche, Rovi, Teva, Pfizer, and Zambon.

J.G.L. has received support for educational courses, lecture honoraria, or travel support from PneumoRx, Pulmonx, Ambu, Bronchus, and Olympus.

I.S.G. has received lecture honoraria or travel support from Laboratorios Bial and Chiesi.

J.J.S.C. has received research grants, lecture or consultancy honoraria, or travel support from AstraZeneca, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Faes, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, and Novartis.

A.T.F. declares no conflicts of interest.