Lung cancer (LC) is the leading cause of cancer-related death. Early detection strategies include LC screening (LCS) with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) and incidental pulmonary nodule clinics (IPNCs). This study describes the structure, workflow, and outcomes of an integrated early diagnosis strategy combining LCS and IPNCs.

MethodsWe conducted a descriptive analysis of a prospective observational study (May 2023–June 2025) implementing an integrated IPNC-LCS model. All IPNC patients underwent initial LC-risk assessment: highly suspicious lesions were referred to a fast-track diagnostic pathway, low-risk patients to primary care (PC), and high-risk individuals to the LCS program. Additional referrals to the LCS program were received from pulmonology clinics and PC. The LCS program followed the I-ELCAP protocol, including LDCT, lung function testing, α1-antitrypsin deficiency (AATD) screening, and smoking cessation support.

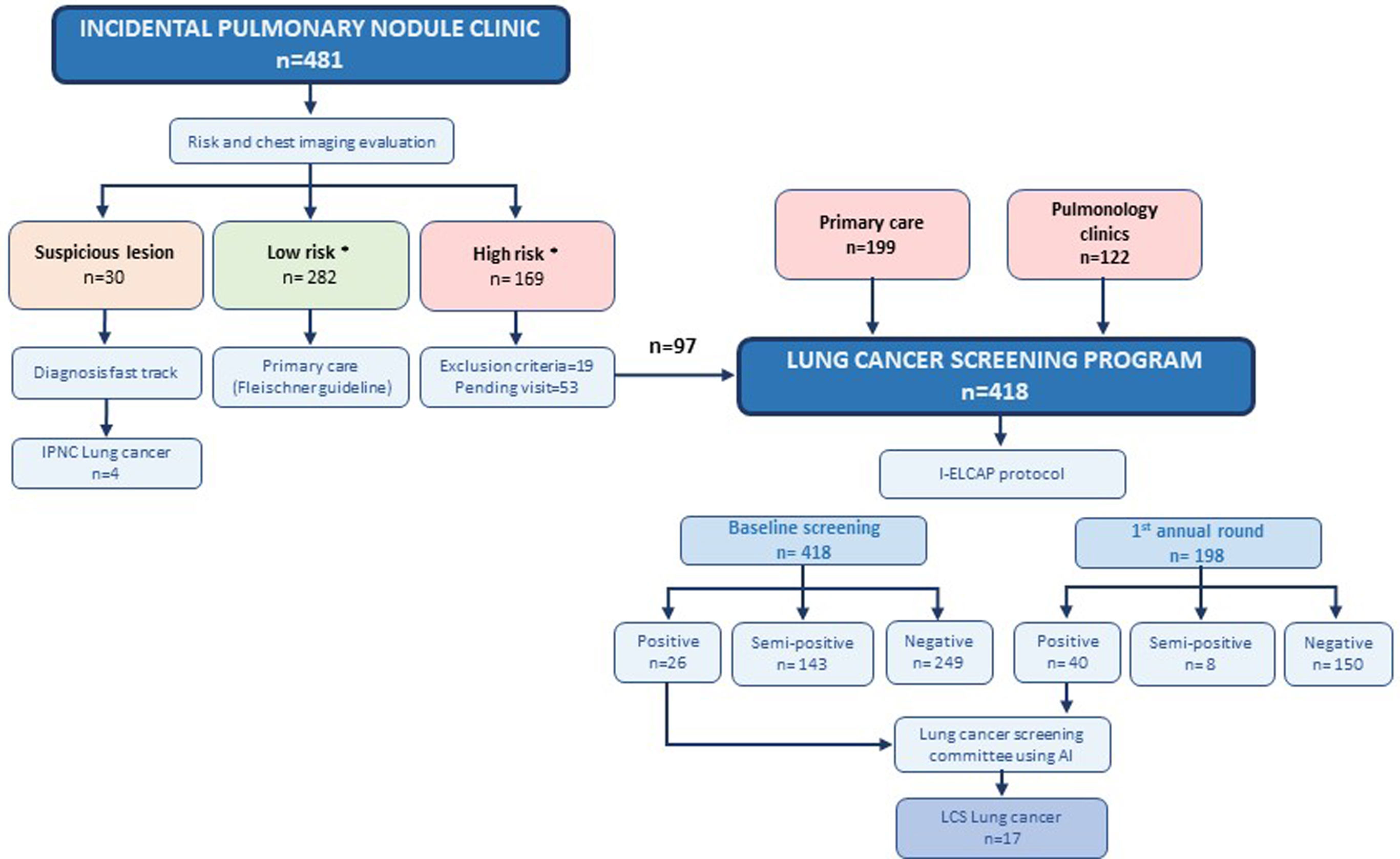

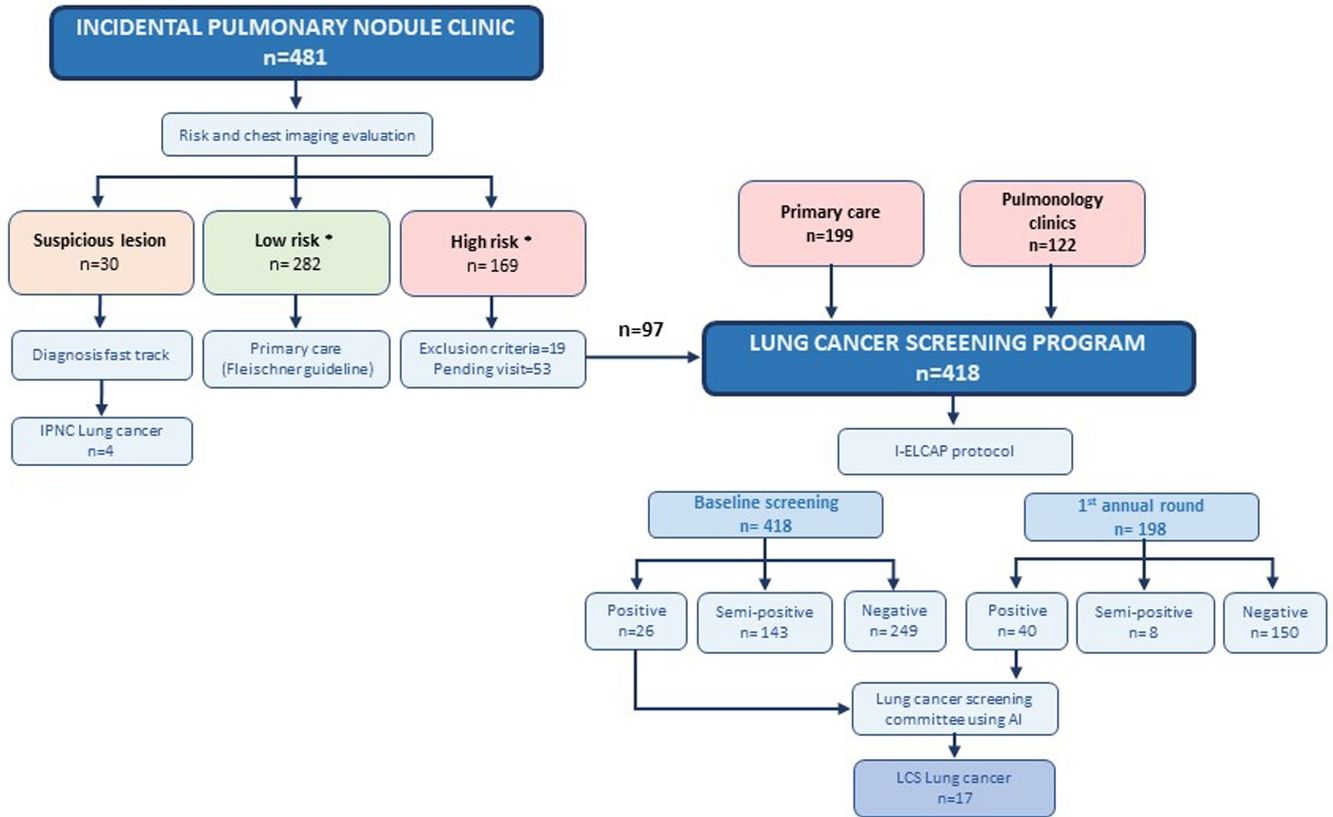

ResultsThe IPNC evaluated 481 individuals: 30 (6.2%) had suspicious lung lesions, with four stage I LC confirmed; 282 (58.6%) were classified as low-risk; and 150 (31.2%) as high risk of whom 97 were enrolled in LCS. The LCS program also received 199 referrals from PC and 122 from pulmonology clinics, totaling 418 participants at baseline (63.2% male; mean age 63.0±6.43 years; 52.9% former smokers; 39.7% with COPD; 67.9% with emphysema). New diagnoses included emphysema (n=106), COPD (n=25), and AATD mutations (n=95). Smoking cessation referral was accepted by 74% of smokers. LC was detected in 17 participants (4.07%), 14 (82.4%) at stage I, all receiving curative-intent treatment.

ConclusionsThis integrated IPNC–LCS model achieved high early-stage LC detection and enabled curative treatment, while uncovering unrecognized respiratory comorbidities and promoting smoking cessation.

El cáncer de pulmón (CP) es la principal causa de muerte por cáncer. Las estrategias de detección precoz incluyen el cribado de CP (CCP) mediante tomografía computarizada de baja dosis (TCBD) y las clínicas de nódulos pulmonares incidentales (CNPI). Este estudio describe la estructura, el flujo de trabajo y los resultados de una estrategia integrada de diagnóstico precoz que combina CCP y CNPI.

MétodosSe realizó un análisis descriptivo de un estudio observacional prospectivo (mayo 2023–junio 2025) que implementó un modelo integrado CNPI–CCP. Los pacientes atendidos en la CNPI fueron sometidos a una evaluación del riesgo de CP. Las lesiones altamente sospechosas se derivaron a un circuito diagnóstico rápido, los pacientes de bajo riesgo a atención primaria (AP), y los individuos de alto riesgo a un programa de CCP, que también recibió derivaciones de consultas de neumología y AP. El programa siguió el protocolo I-ELCAP e incluyó TCBD, pruebas de función pulmonar, cribado de déficit de α1-antitripsina (DAAT) y apoyo para el cese tabáquico.

ResultadosLa CNPI evaluó a 481 individuos: 30 (6,2%) presentaron lesiones pulmonares sospechosas, confirmándose cuatro casos de CP en estadio I; 282 (58,6%) fueron clasificados como de bajo riesgo y 150 de alto riesgo de los cuales 97 se incorporaron al programa de CCP. El programa de CCP recibió además 199 derivaciones desde AP y 122 desde neumología, alcanzando 418 participantes en la evaluación basal (63,2% varones; edad media [DE] 63,0 [6,43] años; 52,9% exfumadores; 39,7% con enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica (EPOC) 67,9% con enfisema). Se identificaron nuevos diagnósticos de enfisema (n=106), EPOC (n=25) y mutaciones de DAAT (n=95). El 74% de los fumadores activos aceptó derivación a deshabituación tabáquica. Se detectó CP en 17 participantes (4,07%), 14 (82,4%) en estadio I, todos con tratamiento con intención curativa.

ConclusionesEste modelo integrado CNPI–CCP logró una alta detección de CP en estadios iniciales y permitió tratamientos curativos, además de identificar comorbilidades respiratorias no diagnosticadas y fomentar el cese tabáquico.

Lung cancer (LC) is the most frequently diagnosed malignancy and remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, accounting for more deaths than colorectal and breast cancers combined.1 In Spain, approximately 20,000 new lung cancer diagnoses occur annually, resulting in 23,239 deaths in the past year alone,2 a figure that is projected to rise in the coming years.3 The overall 5-year survival rate remains low(13.8%), largely because nearly 80% of diagnoses are made at advanced stages, when curative treatment is no longer feasible.4

Improving LC survival requires structured programs for the early detection and management of pulmonary nodules.5 LC may be detected incidentally, during thoracic CT scans performed for unrelated clinical reasons, or through systematic screening, in asymptomatic high-risk individuals undergoing low-dose CT (LDCT) scans. On the one hand, the efficacy of screening strategies has been demonstrated in the International Early Lung Cancer Action Program (I-ELCAP)6,7 and confirmed in randomized trials, including the National Lung Screening Trial(NLST)8 and the NELSON trial.9 These findings prompted endorsements of lung cancer screening(LCS) by the US Preventive Services Task Force and the European Respiratory Society,10,11 and led to the development of large-scale initiatives such as 4-IN-THE-LUNG-RUN12 and the Targeted Lung Health Check program in the UK,13 among others.14–16 However, current implementation remains limited, with fewer than 5% of eligible individuals enrolled in LDCT LCS programs.17 On the other hand, incidental pulmonary nodule clinics(IPNC) may provide a complementary pathway for early detection and serve as an entry point into LCS programs.18,19 This is particularly relevant in Spain, where national LCS initiatives have not yet been adopted and a critical gap remains in cancer prevention policies.20

In this context, we implemented a novel strategy in May 2023 to enhance early LC diagnosis through a dual approach integrating a dedicated virtual IPNC with a LCS program for high-risk individuals. This paper provides an overview of the entire structure, components, and preliminary results of this early diagnosis strategy. Additionally, we describe the specific outcomes of the LCS program, which integrates clinical and radiological data collection, comprehensive respiratory evaluation, biological sample acquisition, and voluntary referral to a smoking-cessation program for current smokers.

Material and methodsStudy design and objectiveThis prospective, ongoing observational study is being conducted between May 2023 and June 2025 at Arnau de Vilanova and Santa Maria University Hospital in Lleida, Catalonia, Spain.

The study adheres to the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) guidelines. It was approved by the local ethics committee (CEIC-2783), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The primary objective was to describe the implementation framework of an early LC detection strategy integrating a dedicated virtual IPNC with a LCS program for high-risk individuals.

The secondary objective was to provide a detailed description of the clinical outcomes of the comprehensive LCS program.

Overall structure of the early diagnosis strategyThe overall structure of the early diagnosis strategy is outlined in Fig. 1. The IPNC, conducted as a virtual consultation, included asymptomatic individuals in whom pulmonary nodules were identified on imaging performed for unrelated clinical indications. Initially, the pulmonary nodule nurse navigator conducted a telephone interview to assess the patient's risk based on age, smoking history, personal and family history of cancer, occupational exposures, and the presence of COPD and/or emphysema. The nurse (AV) also ensured that the patient did not present with any symptoms suspicious for LC. Patients were then classified as low-risk (none of the following criteria) or high-risk if they met all of the following: current or former smokers who quit within the past 15 years, with a tobacco exposure of ≥20 pack-years, and aged between 50 and 80 years. However, the smoking cessation criterion was waived for individuals with COPD or emphysema. Subsequently, all cases and imaging studies were reviewed by three pulmonologists (JG, MZ and CM).

Early diagnosis strategy diagram. *High risk criteria: current or former smokers who quit within the past 15 years, with a tobacco exposure of ≥20 pack-years, and aged between 50 and 80 years. The smoking criteria were waived for individuals with COPD or emphysema, a first-degree family history of LC, or relevant occupational exposure to lung carcinogens. Low risk criteria: not meeting the above. I-ELCAP: International Early Lung Cancer Action Program, CT Biopsy: Computed Tomography-guided Biopsy, FBS: Flexible Bronchoscopy, FNA: Fine Needle Aspiration, EBUS: Endobronchial Ultrasound.

Lesions considered highly suspicious for LC (regardless of the patient's risk profile) were referred directly to the LC diagnostic fast-track consultation for further evaluation. Individuals classified as low-risk (i.e., not meeting the aforementioned criteria) were referred back to primary care (PC) with follow-up recommendations according to the Fleischner Society guidelines.21 The pulmonary nodule nurse navigator(AV) ensured appropriate follow-up for these patients. High-risk individuals (i.e., meeting the aforementioned criteria) were included in the LCS program, conducted through in-person visits, and were followed according to the I-ELCAP protocol.22

The second referral pathway for the LCS program included patients selected from pulmonology outpatient clinics, particularly those with COPD and/or emphysema. The third pathway was direct referral from PC. The province of Lleida includes 23 PC centers, covering an area of 12,173km2 and a population of approximately 446,000 inhabitants. Dissemination of the LCS program and its eligibility criteria was carried out progressively through meetings with PC teams, social media, newspapers, radio, and patient associations. To date, seven PC centers have been actively participating. All referred patients underwent centralized eligibility review to confirm that high-risk criteria were met prior to enrollment.

A dedicated multidisciplinary LCS committee (Fig. 1) was established at the hospital to manage all suspicious lesions. The committee included radiologists, the aforementioned pulmonologists, the nurse navigator, the project manager, thoracic surgeons, radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, and pathologists. Case discussions were conducted on-site once a week.

LCS program cohortThe LCS cohort included high-risk individuals enrolled in a comprehensive screening program through the three referral pathways (Fig. 1) mentioned above: the IPNC, pulmonology outpatient clinics, and PC centers across the province of Lleida. All participants met the predefined high-risk criteria previously described. Exclusion criteria included a current cancer diagnosis, cognitive impairment that limited participation, or a limited life expectancy.

Screening protocol and comprehensive evaluationThe LCS program followed the previously described I-ELCAP protocol.22 As part of the screening process, participants underwent an annual chest LDCT scan, along with a comprehensive respiratory assessment that included complete pulmonary function tests and biobanked serial blood samples for future biomarker research. Current smokers were offered referral to a smoking cessation program. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency(AATD) screening was performed at baseline.

- •

Pulmonary function tests:

Airway function (spirometry, lung volume, and diffusing capacity) was measured in all participants using a flow spirometer (MasterScreen; Jaeger) according to the guidelines of the American Thoracic Society.23 Pulmonary parameters included TLC, FVC, residual volume, FEV1, FEV1 to FVC ratio, and DLCO. The results were expressed as a percentage of the predicted value according to the European Community Lung Health Survey.24 For subjects with obstructive spirometry, postbronchodilation measurements were determined 15min after inhalation of 400μg of salbutamol.

- •

Low-dose chest CT scan examinations

Chest CT scan examinations for patients in the IPNC were typically performed using 128-mm×0.6-mm slice collimation, 0.5-s gantry rotation time, and 2-mm section thickness with a 1-mm reconstruction interval. All the images were acquired with patients in the supine position in the craniocaudal direction at end inspiration. The resulting images were visualized with an image archiving and communication system with standard lung (level, −450 Hounsfield units [HU]; width, 1600HU) and mediastinal (level, 40HU; width, 400HU) windows. The LCS program examinations were performed at low-dose settings (Sn100-kV tube voltage) resulting in a 4–5-fold reduction in radiation exposure.

In general, chest CT examinations were interpreted by the institution's radiologists, with LDCT scans from the LCS program read by a specialist thoracic radiologist (MP). All chest CT images were subsequently reviewed by pulmonologists with specific training in thoracic imaging (JGG), who were also responsible for the LC fast-track diagnostic consultation (MZ and CM). All three participated in the two separate weekly meetings: one for the IPNC and another for the LCS.

To enhance nodule characterization and consistent assessment, the reviewing pulmonologists employed an artificial intelligence (AI)-based software tool (https://contextflow.com/). This AI platform assists in detecting, segmenting, and characterizing pulmonary nodules, providing standardized measurements of nodule size, volume, and morphology, and highlighting suspicious features that may warrant further evaluation. The tool was used as a support system alongside expert clinical judgment.

Radiological emphysema was assessed according to the Fleischner Society consensus.25 Follow-up recommendations were based on Fleischner Society criteria21 for low-risk patients and the I-ELCAP protocol22 for high-risk individuals included in the LCS program (Fig. 1).

- •

Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (AATD) screening

The AATD screening used the A1AT Genotyping Test (Progénika) AlphaKit®, a PCR and hybridization-based test to detect 14 SERPINA1 gene variants, used with the Luminex 200™ instrument (xPONENT® software) and ORAcollect·Dx model OCD-100 for genomic DNA collection via buccal swab.

- •

Lung cancer diagnostic data

LC diagnostic data included information on diagnostic procedures, histological subtype, disease stage according to the 8th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual26 and treatment modality. Diagnosis was attributed to baseline screening if the nodule first appeared on the initial LDCT, regardless of when confirmed. Nodules first seen on annual LDCT were linked to that corresponding screening round.22

StatisticsDescriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics of the study population. Absolute and relative frequencies were used for qualitative data. The Shapiro–Wilk test was applied to assess the normality of quantitative variables, and mean (standard deviation [SD]) or median (25–75th percentiles) were presented as appropriate. R statistical software, version 4.3.1 (R Project for Statistical Computing), was used for all analyses.

Results- •

IPNC evaluation

Of the 481 individuals evaluated at the IPNC, 30 (6.2%) had suspicious lung lesions and underwent further diagnostic work-up through the LC diagnostic fast-track consultation, resulting in the identification of four participants with stage I LC (three adenocarcinomas and one squamous cell carcinoma). Another 282 (58.6%) were classified as low-risk and referred to PC, with no participants in this group diagnosed with LC to date. The remaining 169 (35.1%) were considered high-risk and 150 met eligibility criteria for the LCS program. At the time of analysis, 97 high-risk individuals had completed baseline LDCT and 53 were scheduled for upcoming visits (Fig. 1). The IPNC cohort baseline characteristics are detailed in eTable 1.

- •

Comprehensive LCS baseline evaluation

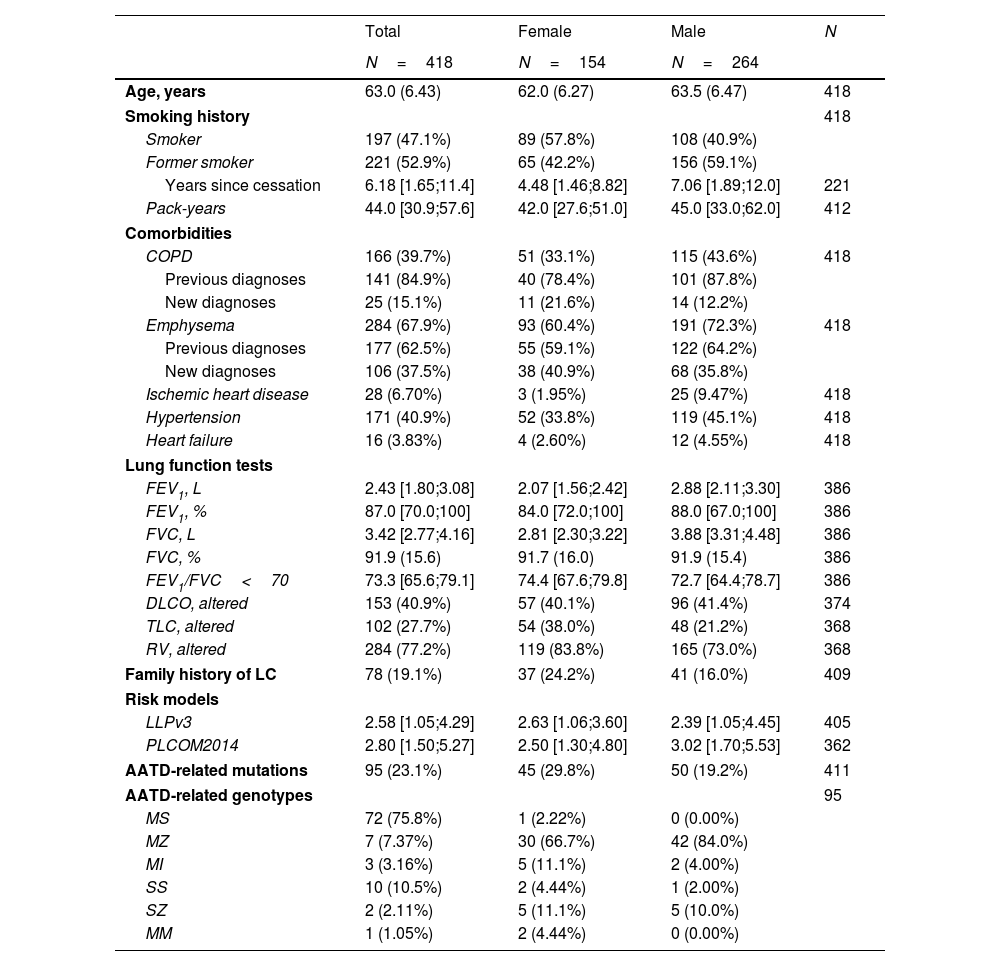

The baseline LCS program included 418 participants: 97 (23.2%) high-risk IPNC referrals, 199 (47.6%) from PC, and 122 (29.2%) from pulmonology clinics (Fig. 1). The cohort was predominantly male (63.2%), with a mean age of 63.0 (6.43) years. Most participants were former smokers (52.9%), with a median pack-year index of 44.0 [30.9;57.6]. Among the 197 (47.1%) current smokers, 146 (74.11%) accepted referral to the smoking cessation clinic. The most frequent comorbidities were emphysema (67.9%), hypertension (40.9%) and COPD (39.7%). Lung cancer risk scores are summarized in Table 1. Lung function tests generally showed preserved spirometry values (Table 1); however, 146 (36.8%) of the LCS cohort had an FEV1/FVC ratio below 70%, indicating airflow obstruction, which led to the identification of 25 (6.0%) individuals with previously undiagnosed COPD. Additionally, 284 (77.2%) showed evidence of air trapping, and 153 (40.9%) exhibited impaired DLCO. Radiological emphysema was newly diagnosed in 106 (25.4%) participants, while AATD mutations were detected in 95 (23.1%), most commonly the S allele (75.8%) (Table 1). None of the participants with detected mutations required specific treatment.

- •

LCS LDCT results: baseline and 1st annual round.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of lung cancer screening program participants.

| Total | Female | Male | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=418 | N=154 | N=264 | ||

| Age, years | 63.0 (6.43) | 62.0 (6.27) | 63.5 (6.47) | 418 |

| Smoking history | 418 | |||

| Smoker | 197 (47.1%) | 89 (57.8%) | 108 (40.9%) | |

| Former smoker | 221 (52.9%) | 65 (42.2%) | 156 (59.1%) | |

| Years since cessation | 6.18 [1.65;11.4] | 4.48 [1.46;8.82] | 7.06 [1.89;12.0] | 221 |

| Pack-years | 44.0 [30.9;57.6] | 42.0 [27.6;51.0] | 45.0 [33.0;62.0] | 412 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| COPD | 166 (39.7%) | 51 (33.1%) | 115 (43.6%) | 418 |

| Previous diagnoses | 141 (84.9%) | 40 (78.4%) | 101 (87.8%) | |

| New diagnoses | 25 (15.1%) | 11 (21.6%) | 14 (12.2%) | |

| Emphysema | 284 (67.9%) | 93 (60.4%) | 191 (72.3%) | 418 |

| Previous diagnoses | 177 (62.5%) | 55 (59.1%) | 122 (64.2%) | |

| New diagnoses | 106 (37.5%) | 38 (40.9%) | 68 (35.8%) | |

| Ischemic heart disease | 28 (6.70%) | 3 (1.95%) | 25 (9.47%) | 418 |

| Hypertension | 171 (40.9%) | 52 (33.8%) | 119 (45.1%) | 418 |

| Heart failure | 16 (3.83%) | 4 (2.60%) | 12 (4.55%) | 418 |

| Lung function tests | ||||

| FEV1, L | 2.43 [1.80;3.08] | 2.07 [1.56;2.42] | 2.88 [2.11;3.30] | 386 |

| FEV1, % | 87.0 [70.0;100] | 84.0 [72.0;100] | 88.0 [67.0;100] | 386 |

| FVC, L | 3.42 [2.77;4.16] | 2.81 [2.30;3.22] | 3.88 [3.31;4.48] | 386 |

| FVC, % | 91.9 (15.6) | 91.7 (16.0) | 91.9 (15.4) | 386 |

| FEV1/FVC<70 | 73.3 [65.6;79.1] | 74.4 [67.6;79.8] | 72.7 [64.4;78.7] | 386 |

| DLCO, altered | 153 (40.9%) | 57 (40.1%) | 96 (41.4%) | 374 |

| TLC, altered | 102 (27.7%) | 54 (38.0%) | 48 (21.2%) | 368 |

| RV, altered | 284 (77.2%) | 119 (83.8%) | 165 (73.0%) | 368 |

| Family history of LC | 78 (19.1%) | 37 (24.2%) | 41 (16.0%) | 409 |

| Risk models | ||||

| LLPv3 | 2.58 [1.05;4.29] | 2.63 [1.06;3.60] | 2.39 [1.05;4.45] | 405 |

| PLCOM2014 | 2.80 [1.50;5.27] | 2.50 [1.30;4.80] | 3.02 [1.70;5.53] | 362 |

| AATD-related mutations | 95 (23.1%) | 45 (29.8%) | 50 (19.2%) | 411 |

| AATD-related genotypes | 95 | |||

| MS | 72 (75.8%) | 1 (2.22%) | 0 (0.00%) | |

| MZ | 7 (7.37%) | 30 (66.7%) | 42 (84.0%) | |

| MI | 3 (3.16%) | 5 (11.1%) | 2 (4.00%) | |

| SS | 10 (10.5%) | 2 (4.44%) | 1 (2.00%) | |

| SZ | 2 (2.11%) | 5 (11.1%) | 5 (10.0%) | |

| MM | 1 (1.05%) | 2 (4.44%) | 0 (0.00%) | |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, FVC: forced vital capacity, FEV1: forced expiratory volume in first second, TLC: total lung capacity, RV: residual volume, LC: lung cancer, PLCOM2014: Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial Model 2017, LLPv3: Liverpool Lung Project lung cancer risk stratification model v3. Data are presented as n (%), mean (SD) or median [IQR].

As represented in Fig. 1, LCS baseline LDCT results were classified as negative in 249 (59.6%) participants, semi-positive in 143 (34.2%), and positive in 26 (6.2%). At the time of analysis, 198 subjects had completed the1st annual LDCT screening round, in which 150 (75.8%) scans were negative, 8 (4.0%) were semi-positive, and 40 (20.2%) positive.

- •

LC diagnostic outcomes of the LCS program

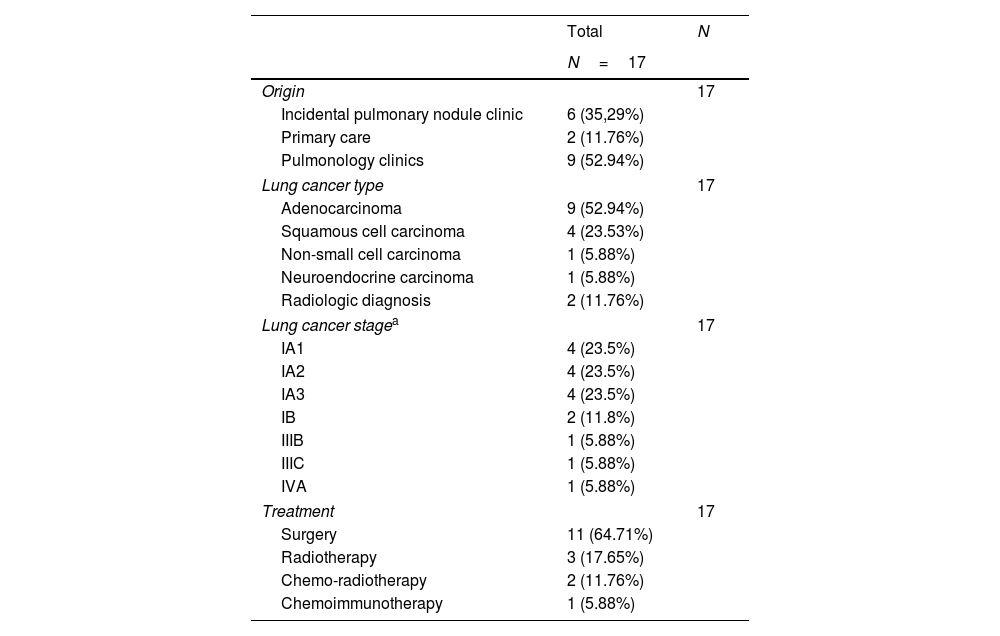

Seventeen individuals with LC (4.07%) were diagnosed following positive LDCT results in the LCS program. Sixteen lesions were visible at baseline screening, regardless of the timing of diagnosis, and one lesion was newly detected in the 1st annual round. Nine of the diagnosed individuals were referred from pulmonary outpatient clinics, six from the IPNC (two of which were newly identified lesions on baseline LDCT), and two from PC. No interval LCs were observed to date.

Differences between participants diagnosed with LC and LCS participants without LC are detailed in eTable 2. Notably, all 17 LC patients were male, had emphysema, and 14 (82.4%) also had COPD. The stages and histologic types of LC are presented in Table 2. The majority of participants were diagnosed at stage I (n=14, 82.4%), whereas three participants were diagnosed at stages IIIB, IIIC, and IVA, respectively. The majority were adenocarcinomas (n=9, 52.9%), followed by squamous cell carcinomas (n=4, 23.5%). Surgical resection was the predominant treatment modality (n=11, 64.7%), while 3 (17.6%) patients received stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) with curative intent.

Type, stage at diagnosis, and treatment of participants with lung cancer detected in the lung cancer screening program.

| Total | N | |

|---|---|---|

| N=17 | ||

| Origin | 17 | |

| Incidental pulmonary nodule clinic | 6 (35,29%) | |

| Primary care | 2 (11.76%) | |

| Pulmonology clinics | 9 (52.94%) | |

| Lung cancer type | 17 | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 9 (52.94%) | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 4 (23.53%) | |

| Non-small cell carcinoma | 1 (5.88%) | |

| Neuroendocrine carcinoma | 1 (5.88%) | |

| Radiologic diagnosis | 2 (11.76%) | |

| Lung cancer stagea | 17 | |

| IA1 | 4 (23.5%) | |

| IA2 | 4 (23.5%) | |

| IA3 | 4 (23.5%) | |

| IB | 2 (11.8%) | |

| IIIB | 1 (5.88%) | |

| IIIC | 1 (5.88%) | |

| IVA | 1 (5.88%) | |

| Treatment | 17 | |

| Surgery | 11 (64.71%) | |

| Radiotherapy | 3 (17.65%) | |

| Chemo-radiotherapy | 2 (11.76%) | |

| Chemoimmunotherapy | 1 (5.88%) | |

During the diagnostic work-up of positive findings, one surgical resection yielded a benign lesion (presurgical biopsy was not feasible), another surgical biopsy was benign, and in one surgical case the specimen could not be analyzed due to technical issues. The two participants with radiologically diagnosed LC (Table 2) remain under clinical and radiological surveillance: one patient's surgical specimen was damaged and could not be evaluated by the pathologists, and the other patient did not undergo biopsy due to clinical contraindications and received SBRT. These two cases were carefully reviewed by the LCS committee, and all members agreed on the diagnosis of lung cancer despite the lack of a confirmatory histopathological diagnosis. Importantly, no deaths attributable to LC or its treatment were observed among the 17 diagnosed participants during the current follow-up period.

DiscussionThis is the first report in Spain to describe an innovative early LC diagnosis strategy that integrates an IPNC with a comprehensive LCS program—including respiratory assessment—both closely linked to PC and monitored by a nurse navigator. The report summarizes the first two years of an ongoing implementation, during which the infrastructure and technology of the existing virtual IPNC were adapted to launch an LCS program, aiming to optimize available resources for early LC detection with active PC involvement.

This strategy enabled the appropriate management of 481 individuals with incidental pulmonary nodules and facilitated the enrollment of 418 participants in the LCS program, for a total of 802 participants. Among these 418 high-risk individuals ultimately included in the LCS program (199 from PC, 122 from pulmonary consultations, and 97 from IPNC), the LC prevalence was 4.07%. This detection rate exceeds those reported in large-scale trials (eTable 3), likely due to the inclusion of individuals with pulmonary nodules and a high prevalence of COPD and emphysema—both known risk factors for LC.27–29 These results support the integration of IPNCs into LCS programs and underscore the need to refine eligibility criteria to improve diagnostic yield and cost-effectiveness by focusing on high-risk profiles, thereby reducing the number needed to screen.30,31 The rate of early-stage LC (n=14, 82.4%) subjects diagnosed at stage I and the predominance of adenocarcinomas are consistent with other cohorts (eTable 3), particularly the I-ELCAP32 study. Moreover, LC detected via the IPNC showed similar biological characteristics (stage and histology) to those identified through LCS, as previously described,33 further supporting the integration of both diagnostic pathways. This is particularly relevant given that LCS implementation is often hindered by the lack of infrastructure34; IPNCs can help identify and recruit eligible individuals, facilitating program expansion.

The value of IPNCs in supporting early LC diagnosis and appropriate management is well established, especially when CT scans are reviewed by pulmonologists trained in LC and interventional pulmonology, which helps minimize unnecessary invasive procedures.18,35 Our model includes such expertise, complemented by specialized training in thoracic imaging and artificial intelligence (AI)-based software for nodule detection and characterization. This is particularly relevant given the limited adherence to guideline-based nodule management among radiologists—reported between 34% and 60%36—which can result in inadequate follow-up in up to two-thirds of patients.37 AI tools may help mitigate these gaps, especially in detecting small nodules.38 Notably, no participants in the low-risk group monitored in PC were diagnosed with LC, suggesting effective risk stratification and the clinical safety of our approach. These findings highlight the importance of expert-led imaging review, structured clinical pathways, and coordinated patient navigation. In our experience, nurse navigators played a key role in linking nodule management and the LCS program with PC, ensuring continuity and coordination throughout the process.5,18

The comprehensive respiratory evaluation led to new diagnoses of COPD (n=25, 6.0%), emphysema (n=106, 25.4%), and AATD-related mutations (n=95, 23.1%). Although screening for other smoking-related diseases is not routinely included in LCS programs, growing evidence supports its value—particularly in the early identification of lung function impairment and emphysema.27–29 The detection of AATD-related mutations, rarely assessed in LCS settings, may have clinical relevance, as evidence suggests a higher LC risk in carriers, especially for adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.39 These findings support a broader “lung health check” approach, as adopted in the UK Targeted Lung Health Check program,13,31 where early detection of comorbidities may prompt smoking cessation, pharmacological treatment, and genetic counseling, potentially reducing morbidity and refining individual risk stratification.40

The main strengths of this study are: (1) its prospective design and thorough patient characterization; (2) the availability of imaging and biological samples for future research; and (3) the innovative integration of an IPNC with a LCS program, coordinated with PC through nurse navigators, and supported by a dedicated LCS committee enhanced with artificial intelligence tools. However, some limitations should be noted. First, this study is essentially a descriptive, observational analysis of an implemented early-diagnosis strategy, without a control or comparison group. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted as observational evidence. Second, the relatively small sample size limits statistical power and generalizability compared to larger multicenter studies and it should be noted that not all PC centers in the region participated; therefore, implementation was not fully systematic, which may influence comparisons with more population-wide screening cohorts. Third, participant perspectives on the acceptability of the screening process were not formally assessed, despite their relevance for recruitment, adherence, and program sustainability. Finally, the comprehensive respiratory assessment, although valuable, added complexity to data collection and required specialized resources, which may limit feasibility in settings with fewer resources.

In conclusion, our findings support the feasibility of implementing LCS program in our public health system and provide evidence that this approach enables the detection of LC at curable stages. The strategy of integrating the LCS program with an IPNC may represent a key initial step in the implementation process, as it facilitates the identification of high-risk, eligible patients. When integrated with a comprehensive lung health assessment, this approach not only improves the efficiency of LC detection—particularly in populations enriched for emphysema and COPD—but also offers the opportunity to investigate previously unrecognized risk factors and promote smoking cessation. This integrated strategy may help reduce the number needed to screen and maximize the likelihood of diagnosing LC at earlier, more treatable stages. The data collected provide a solid foundation for understanding the performance and challenges of implementing such programs on a national scale.

Ethics statementThe study adheres to the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) guidelines. It was approved by the local ethics committee (code CEIC-2783), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Artificial intelligence involvementChatGPT was used to assist with language review during the preparation of this manuscript. The content was subsequently reviewed and edited by the authors, who take full responsibility for its accuracy and integrity.

Sources of supportAS-C was supported by Departament de Salut (Pla Estratègic de Recerca i Innovació en Salut (PERIS): SLT028/23/000191), SS was supported by Departament de Salut (Pla Estratègic de Recerca i Innovació en Salut (PERIS): SLT035/24/000025), DdGC has received financial support from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Miguel Servet 2020: CP20/00041), co-funded by the European Union. FB is supported by the ICREA Academia program, Generalitat de Catalunya.

Author's contributionsConceptualization (AS-C, JG), data curation (EG-L, AS-C, NR-S), formal analysis (EG-L, IDB, AS-C, JG), investigation (all), methodology (JG, AS-C, SS, CM), project administration (JG, AS-C, NR), supervision (JG, FB, CH), writing – original draft (AS-C, JG), and writing – review & editing (all). All authors provided final approval of the version submitted for publication.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare not to have any conflicts of interest that may be considered to influence directly or indirectly the content of the manuscript.