Brugada syndrome is an autosomal dominant inherited channelopathy that affects the sodium channels of cardiac cell membranes. It is more frequent in young patients, and diagnosis is based on electrocardiographic (ECG) criteria and clinical history of syncope, or family history of sudden death due to malignant ventricular arrhythmias. Three different Brugada ECG patterns have been described: 1) type I, characterised by a coved-type ST-segment elevation≥2mm in more than one right precordial lead (V1-V3), followed by negative T wave; this is considered the only diagnostic type of pattern; (2) type II, characterised by an ST-segment elevation≥2mm in right precordial leads followed by positive or biphasic T wave resulting in a saddle-back configuration; and 3) type III, defined as either of the 2 previous types with ST-segment elevation≤1mm.1,2

Furthermore, several situations and drugs are reported to trigger an ECG pattern of Brugada syndrome.

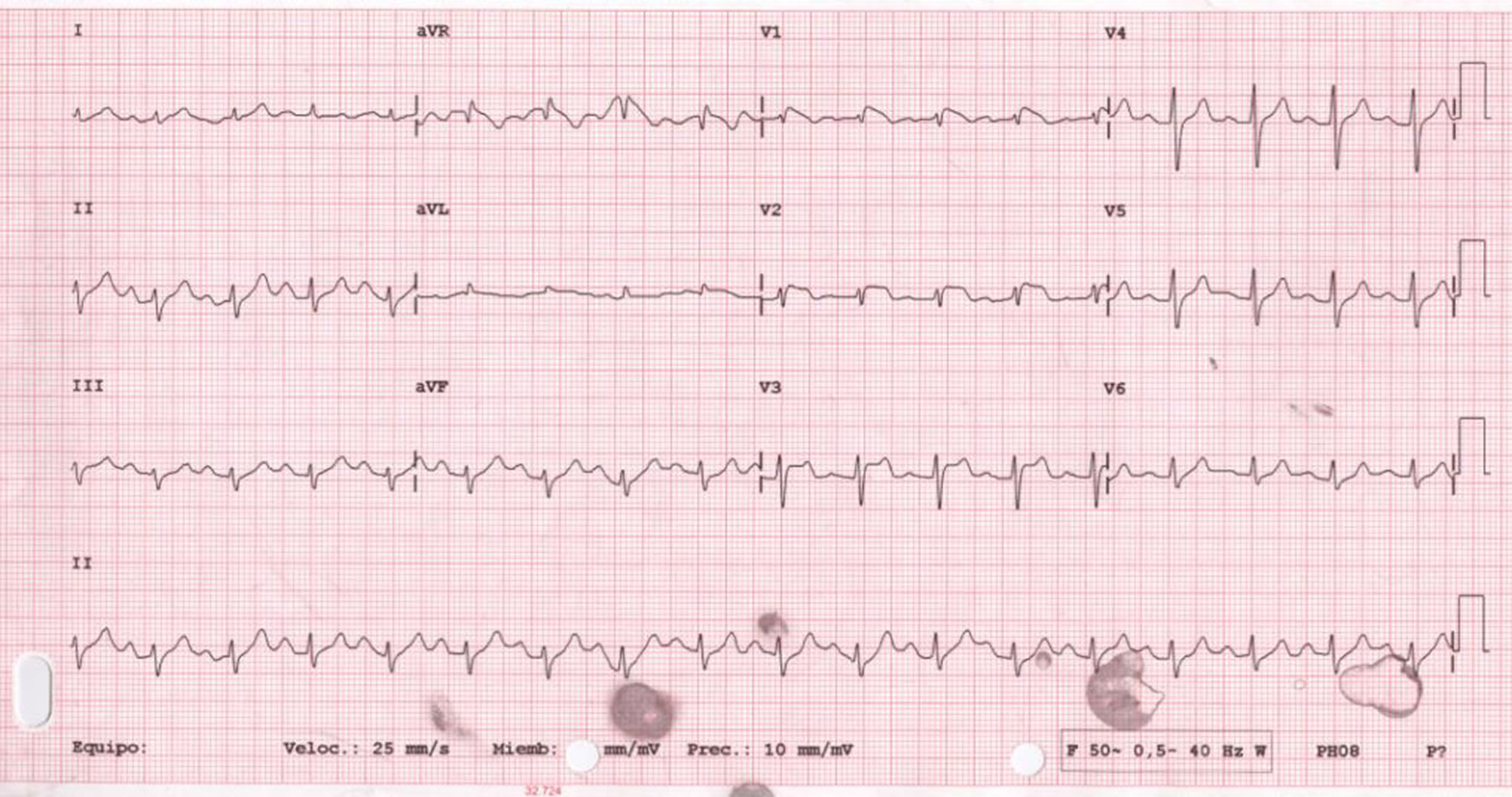

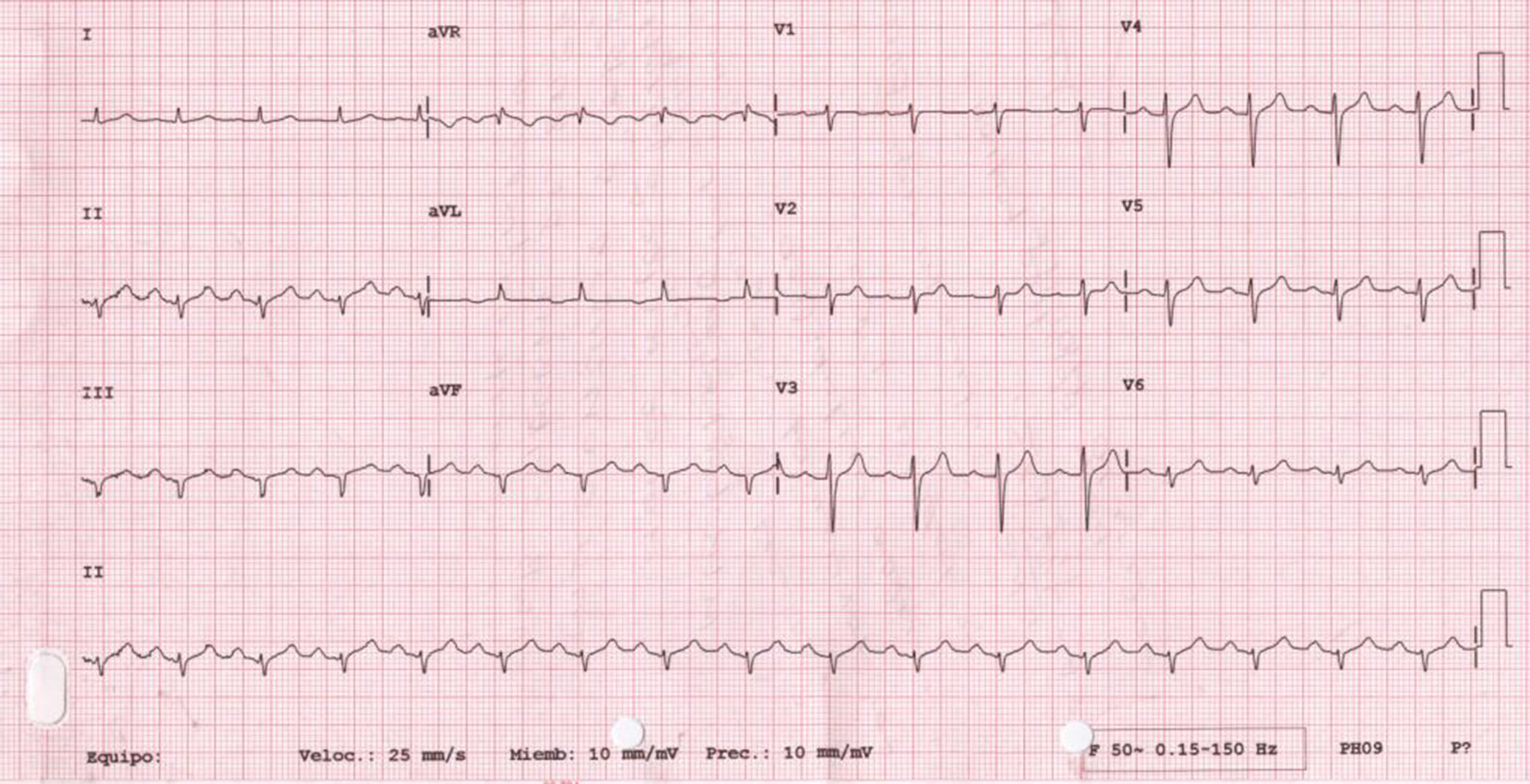

We present the case of a 56-year-old woman with history of smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidaemia, treated with insulin, metformin, valsartan/hydrochlorothiazide, and atorvastatin. She was also taking topiramate and levetiracetam for epilepsy and amitriptyline for depression. At baseline, she showed significant limitations due to moderate cognitive impairment. No family history of sudden death was reported. She was admitted to our hospital due to vasovagal syncope in a context of common cold with fever not exceeding 38°C. The first ECG revealed sinus rhythm with first-degree atrioventricular block, with ST-segment elevation of 1mm in V1-V3 and negative T wave in V1-V2 (Fig. 1). The initial blood analysis showed: creatinine 2.2mg/dL; sodium 136mEq/L; potassium 4.7mEq/L; magnesium 1.2mEq/L; pH 7.32; and troponin I<0.01ng/mL. As acute anteroseptal ST-elevation myocardial infarction was suspected, we consulted the haemodynamics department, who, considering the uncertain diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome and the patient's physical and cognitive impairment, recommended completing a cardiology study and performing an enzyme series, which revealed no abnormalities. An echocardiography revealed left ventricular hypertrophy with normal ejection fraction and no alterations in segmental contractility. The patient progressed favourably, with complete resolution of the infection and normalised kidney function (creatinine at discharge 0.78mg/dL). An ECG performed 48 hours after admission showed that alterations in the previous study had disappeared (Fig. 2). A Holter ECG study revealed no significant arrhythmic events. The patient, who was taking drugs capable of inducing type 1 Brugada pattern (amitriptyline), was discharged with diagnosis of Brugada phenocopy (BrP) probably secondary to impaired kidney function, with no associated alterations in electrolyte levels. Considering the patient's significant physical and cognitive impairment, a flecainide test was not performed. We discussed the case with the neurology department with a view to adjusting or discontinuing amitriptyline.

BrPs are characterised by ECG patterns identical to type 1 or 2 Brugada patterns despite absence of true congenital Brugada syndrome. Their clinical causes include hyperkalaemia, adrenal insufficiency, hypothermia, mechanical chest compression, myocarditis, pericarditis, or ischaemia. The current diagnostic criteria for BrP are: 1) the ECG pattern has a Brugada type 1 or type 2 morphology; 2) the patient has an underlying condition that is identifiable; 3) the ECG pattern resolves after resolution of the underlying condition; 4) there is a low clinical pretest probability of true Brugada syndrome determined by lack of symptoms, medical history, and family history; 5) the results of provocative testing with flecainide, procainamide, ajmaline, or other sodium channel blockers are negative; 6) provocative testing is not mandatory if there has been surgical manipulation of the outflow tract in the previous 96hours; and 7) the results of genetic testing are negative (not a mandatory criterion, because the SCN5A mutation is identified in only 20%-30% of probands affected by true Brugada syndrome).3 Furthermore, several psychoactive drugs, including lithium, amitriptyline, nortriptyline, oxcarbazepine, and clomipramine are contraindicated in patients with Brugada syndrome due to their potential to block sodium channels, which may induce the appearance of malignant arrhythmias, syncope, or sudden cardiac death.4,5 Such other drugs as topiramate or levetiracetam are not contraindicated for these patients. This article describes a possible BrP in a patient receiving amitriptyline, a probable cause according to the modified Karch and Lasagna algorithm,6 in the context of transient kidney dysfunction with no evidence of electrolyte imbalance.

Please cite this article as: Fernández-Anguita MJ, Martínez-Mateo V, Cejudo Díaz del Campo L, Galindo-Andugar MÁ. Patrón de Brugada en paciente tratada con amitriptilina. Neurología. 2020;35:138–140.