Abdominal infections caused by bacteria of the genus Clostridioides are associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality,1–3 especially in immunosuppressed individuals.1 The most severe infections are caused by C. perfringens and C. septicum due to their blood cell tropism,1–3 causing intravascular haemolysis, with disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), which may lead to multiple organ failure.4 However, C. difficile infection is increasingly frequent in our setting. It is associated with inappropriate use of such drugs as antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors and a wide range of comorbidities. C. difficile infection may cause symptoms of varying severity, ranging from mild gastrointestinal symptoms to pseudomembranous colitis and toxic megacolon.5C. difficile toxins induce a proinflammatory state, causing systemic complications.1–3

We report the case of a patient admitted due to C. difficile infection, who presented DIC and subsequently cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST).

The patient was a 46-year-old woman who visited the emergency department due to a one-week history of haemorrhagic diarrhoea and abdominal pain, with fever developing over the previous 48hours. She had history of bilateral salpingectomy due to pelvic inflammatory disease, and chronic consumption of proton pump inhibitors; in the preceding days, she had been receiving amoxicillin and clavulanic acid following tooth extraction.

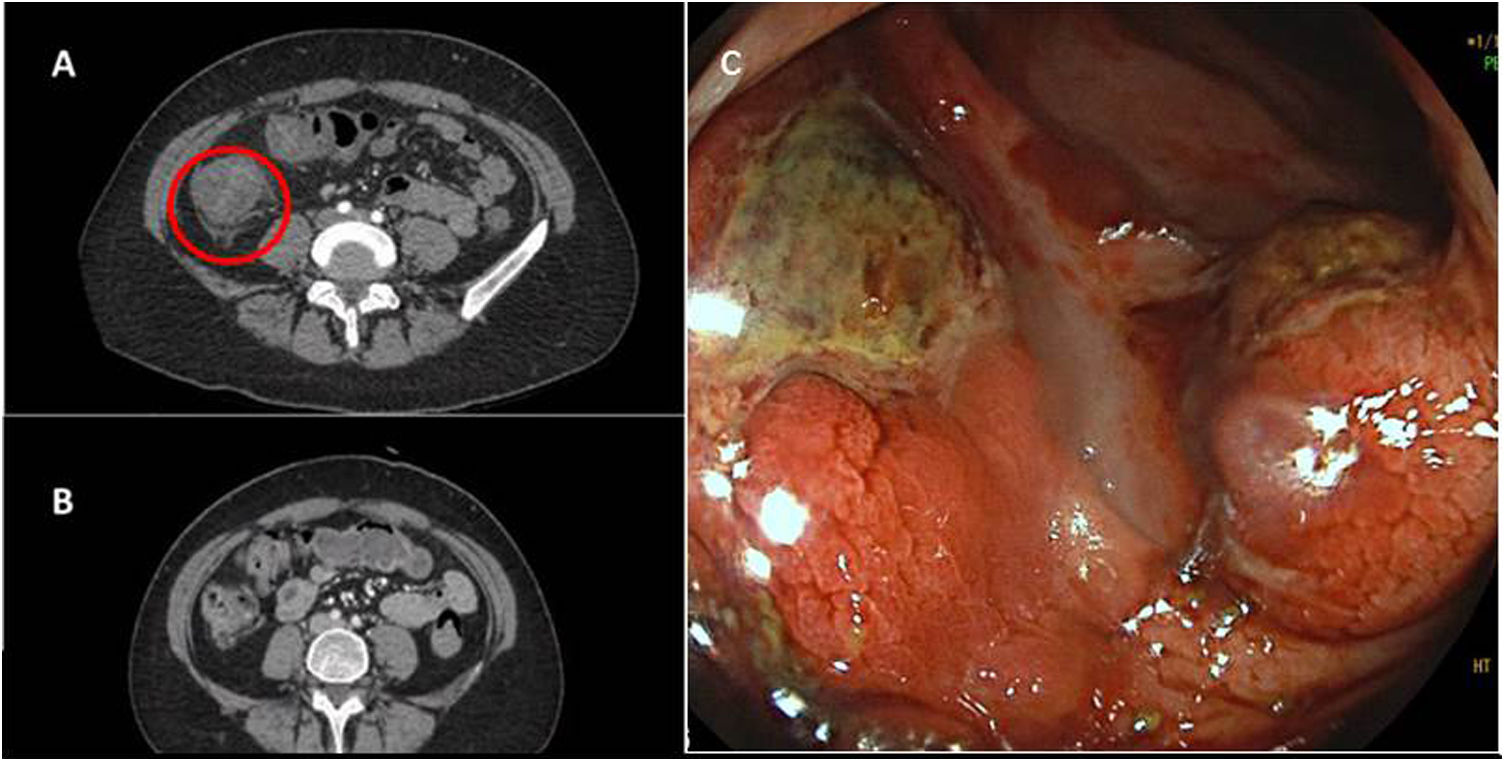

The patient was haemodynamically stable and presented no peritoneal signs. Support measures were started. A blood analysis revealed high levels of acute-phase reactants, moderate thrombocytopaenia (70,000platelets/mm3), and high D-dimer levels (3566μg/L). A polymerase chain reaction test for SARS-CoV-2 yielded negative results. An abdomen CT scan with contrast revealed signs of extensive colitis (Fig. 1). Due to suspicion of enteroinvasive colitis, the patient was admitted and started on broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy.

A) Abdominal CT with contrast performed at admission revealed bowel wall thickening with submucosal oedema in the ascending colon; these findings are compatible with colitis. B) Abdominal CT with contrast performed at discharge, showing resolution of inflammatory signs. C) Colonoscopy image showing fibrinated ulcerations in the transverse colon.

A colonoscopy performed the following day revealed extensive colitis with multiple deep, fibrinated ulcers (Fig. 1). Abdominal pain and haemorrhagic diarrhoea persisted, and the patient presented petechiae in the distal limbs. An additional blood analysis revealed increased severity of thrombocytopaenia, signs of coagulopathy, and elevated levels of liver enzymes. A glutamate dehydrogenase test yielded positive results for C. difficile, and treatment was started with oral vancomycin.

On the third day of hospitalisation, the patient presented sudden-onset mixed aphasia, and code stroke was activated. An emergency blood analysis revealed 35 000 platelets/mm3, a prothrombin time of 45s, fibrinogen level of 195mg/dL, and D-dimer level of 5000μg/L. A head CT scan revealed a hypodense lesion in the left occipitotemporal region and cavernous sinus asymmetry. The patient was transferred to the reference stroke unit. A CT angiography study confirmed left CVST associated with venous infarction in the context of DIC. She received platelet transfusion and treatment with corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulins, and perfusion of heparin sodium, which was subsequently switched to low–molecular weight heparin. Fidaxomicin was also added to treat the C. difficile infection.

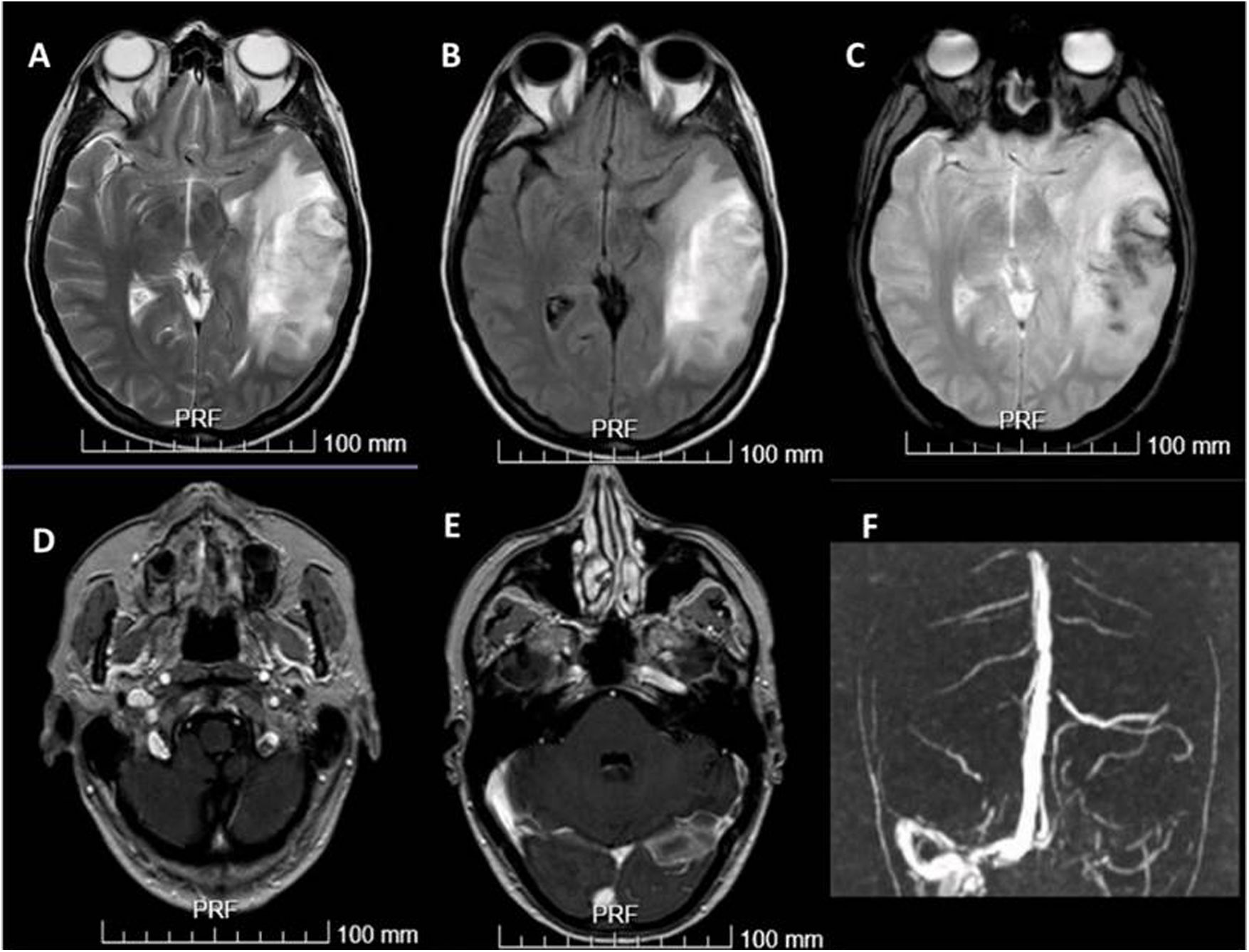

The extension of the brain lesion was evaluated with MRI angiography (Fig. 2). Studies were performed to detect the trigger factor of DIC, including a thrombophilia study (acute phase and delayed), serology tests, an autoimmunity study, full body CT, and gynaecological ultrasound; results were normal, revealing radiological improvement of colitis (Fig. 1).

Brain MRI and MRI angiography. A and B) Hyperintense lesion on T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences compatible with venous haemorrhagic infarction. C) Echo-gradient sequence showing haemosiderin deposits. D and E) Post-contrast T1-weighted sequence revealing obstruction of the left jugular vein and left venous sinuses. F) Brain MRI angiography revealed venous sinus thrombosis of the left sigmoid and left transverse sinuses and torcula.

Aphasia improved with speech therapy. The patient received anticoagulation treatment for 6 months. Liver enzymes levels decreased slowly, reaching normal levels at 8 months; the alteration in liver enzyme levels was attributed to the intercurrent process.

Several clinical conditions, particularly those associated with systemic inflammation, such as sepsis, neoplasia, and trauma, may trigger coagulation, with extremely severe consequences.6 This process is known as DIC, and consists of thrombocytopaenia, prolonged prothrombin and thromboplastin times, and increased levels of fibrin degradation products. Thrombocytopaenia is caused by consumption of platelets in fibrin clots, impairing microcirculation and potentially leading to multiple organ dysfunction and thromboembolic and haemorrhagic events.6

Although C. difficile infection rarely causes DIC, it has recently been associated with higher rates of deep vein thrombosis in hospitalised patients, leading to higher mortality rates.7,8 A recent report describes the case of a patient with respiratory tract infection due to SARS-CoV-2 and abdominal infection due to C. difficile who presented portal vein thrombosis; the causal mechanism was thought to be the combination of infection and coagulopathy secondary to COVID-19.9

Other gastrointestinal disorders, such as inflammatory bowel disease, have been linked to venous and arterial thrombotic events, with the most frequent being ulcerative colitis.10,11 Intestinal inflammation present in Crohn disease has been suggested as a predisposing factor for the coagulopathy underlying CVST.12,13

This is the first reported case of CVST in the context of DIC in a patient with no predisposing factor other than gastrointestinal C. difficile infection.

Please cite this article as: Alba Isasi MT, García Núñez DF, Navarro García JC, Valero López G. Trombosis de senos venosos secundaria a coagulación intravascular diseminada tras infección por Clostridioides difficile. Neurología. 2022;37:499–501.