Previous official clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for epilepsy were based on expert opinions and developed by the Epilepsy Study Group of the Spanish Society of Neurology (GE-SEN).

The current CPG in epilepsy is based on the scientific method, which extracts recommendations from published scientific evidence. Reducing variability in clinical practice through standardisation of medical practice is its main function.

Scope and objectivesThis CPG focuses on comprehensive care for individuals affected by epilepsy as a primary and predominant symptom, regardless of the age of onset and medical policy.

Methodology(1) Creation of a working group of GE-SEN neurologists, in collaboration with neuropediatricians, neurophysiologists and neuroradiologists. (2) Identification of clinical areas to be covered: diagnosis, prognosis and treatment. (3) Search and selection of the relevant scientific evidence. (4) Formulation of recommendations based on the classification of the available scientific evidence.

ResultsThe CPG contains 161 recommendations of which 57% were established by consensus between authors and publishers, due to significant lack of awareness of this disorder in many fields.

ConclusionsThis epilepsy CPG formulates recommendations based on explicit scientific evidence as a result of a formal and rigorous methodology, according to the current knowledge in the pre-selected areas.

This paper includes the CPG chapter dedicated to emergency situations in seizures and epilepsy. These may present as a first seizure, an unfavourable outcome in a patient with known epilepsy, or status epilepticus (SE) as the most severe manifestation.

Las anteriores Guías oficiales de práctica clínica en epilepsia elaboradas por el Grupo de Estudio de Epilepsia de la Sociedad Española de Neurología (GE-SEN) estaban basadas en la opinión de expertos.

La actual Guía de práctica clínica (GPC) en epilepsia se basa en el método científico que extrae recomendaciones a partir de evidencias científicas constatadas. Su principal función es disminuir la variabilidad de la práctica clínica a través de la homogeneización de la práctica médica.

Alcance y objetivosEsta GPC se centra en la atención integral de personas afectadas por una epilepsia, como síntoma principal y predominante, independiente de la edad de inicio y ámbito asistencial.

Metodología1) Constitución del grupo de trabajo integrado por neurólogos del GE-SEN, con la colaboración de neuropediatras, neurofisiólogos y neurorradiólogos; 2) determinación de los aspectos clínicos a cubrir: diagnóstico, pronóstico y tratamiento; 3) búsqueda y selección de la evidencia científica relevante; 4) formulación de recomendaciones basadas en la clasificación de las evidencias científicas disponibles.

ResultadosContienen 192 recomendaciones. El 57% son de consenso entre autores y editores, como consecuencia del desconocimiento en muchos campos de esta patología.

ConclusionesEsta GPC, en epilepsia, con una metodología formal y rigurosa en la búsqueda de evidencias explícitas donde ha sido posible, formula recomendaciones extraídas de las mismas.

En este artículo incluimos el capítulo de la GPC dedicado a situaciones de urgencia en crisis epilépticas y epilepsia, que pueden presentarse como una primera crisis epiléptica, una evolución desfavorable en un paciente con una epilepsia conocida o en su forma más grave como un estado epiléptico.

Epilepsy refers to a heterogeneous array of highly prevalent illnesses, and it is regarded as one of the most common reasons for neurological consultation. Epilepsy may be defined as a brain disorder characterised by a long-term predisposition to epileptic seizures (ES), and by the neurobiological, cognitive, psychological, and social consequences of that disorder. Diagnosis must be preceded by at least one ES. This is one of the diseases with the greatest impact on patients’ quality of life.

The Epilepsy Study Group of the Spanish Society of Neurology (GE-SEN) has published two previous editions of the official guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of epilepsy. These guidelines were fundamentally based on expert opinion. The current guidelines, drawn up during 2012, are based on the scientific method, which uses confirmed evidence to formulate recommendations.

This study group comprises 47 epilepsy experts, including neurologists, neurophysiologists, neuroradiologists, and paediatric neurologists. The Guidelines were coordinated by five editors under a general director.

Recommendations for searching and selecting applicable scientific evidence are described below.

- 1.

Selective keyword search on PubMed-MEDLINE, using scientific evidence filters to select meta-analyses and controlled clinical trials.

- 2.

Other search engines used to gather evidence:

- -

Tripdatabase (www.tripdatabase.com).

- -

Cochrane Library/Cochrane Library Plus (http://www.update-software.com/Clibplus/Clibplus.asp).

- -

Search engines for treatment data: DARE (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/crdweb).

- -

For prognoses and aetiology: EMBASE (http://www.embase.com).

- -

- 3.

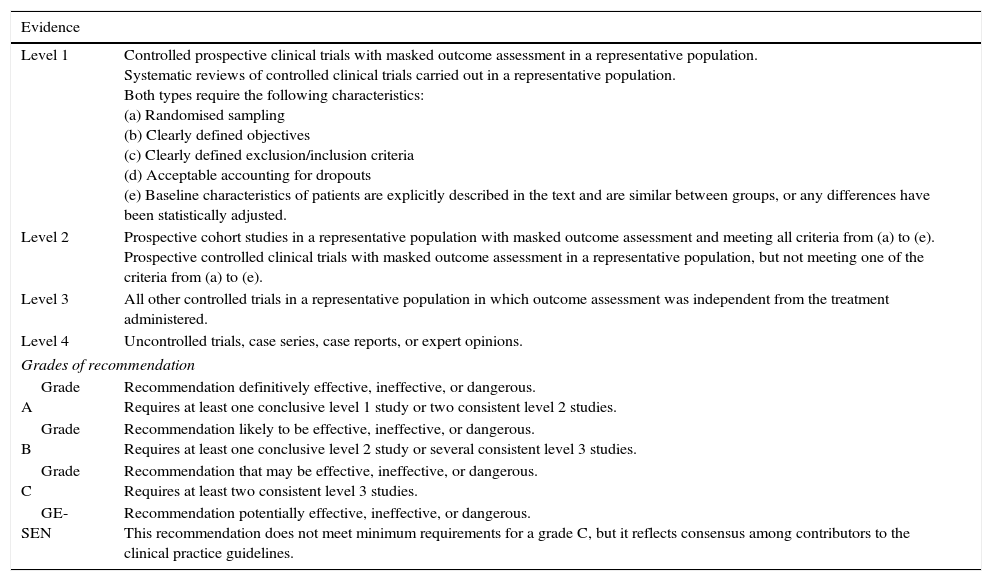

Information from other clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) or recommendations by medical societies: American Academy of Neurology, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, International League Against Epilepsy, European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS), Guía oficial para el diagnóstico y tratamiento de la epilepsia SEN 2008, and Guía andaluza de epilepsia 2009. The study group adheres to the 2004 EFNS instructions for classifying scientific evidence (Table 1).1

Table 1.Classification of level of evidence for therapeutic actions

Evidence Level 1 Controlled prospective clinical trials with masked outcome assessment in a representative population.

Systematic reviews of controlled clinical trials carried out in a representative population.

Both types require the following characteristics:

(a) Randomised sampling

(b) Clearly defined objectives

(c) Clearly defined exclusion/inclusion criteria

(d) Acceptable accounting for dropouts

(e) Baseline characteristics of patients are explicitly described in the text and are similar between groups, or any differences have been statistically adjusted.Level 2 Prospective cohort studies in a representative population with masked outcome assessment and meeting all criteria from (a) to (e).

Prospective controlled clinical trials with masked outcome assessment in a representative population, but not meeting one of the criteria from (a) to (e).Level 3 All other controlled trials in a representative population in which outcome assessment was independent from the treatment administered. Level 4 Uncontrolled trials, case series, case reports, or expert opinions. Grades of recommendation Grade A Recommendation definitively effective, ineffective, or dangerous.

Requires at least one conclusive level 1 study or two consistent level 2 studies.Grade B Recommendation likely to be effective, ineffective, or dangerous.

Requires at least one conclusive level 2 study or several consistent level 3 studies.Grade C Recommendation that may be effective, ineffective, or dangerous.

Requires at least two consistent level 3 studies.GE-SEN Recommendation potentially effective, ineffective, or dangerous.

This recommendation does not meet minimum requirements for a grade C, but it reflects consensus among contributors to the clinical practice guidelines. - 4.

For prognostic studies, we used a modified version of the evidence grading system promoted by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine.

- 5.

Where scientific evidence was lacking, we followed the general instructions in CPGs issued by other medical societies considering that absence of proof should not be considered proof of inefficacy, that is, ‘absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.’ In such cases, the recommendation is graded by consensus of the medical society itself. In our case, we assigned the recommendation based on consensus of the GE-SEN.

The Guidelines contain a total of 193 recommendations, some of which are expressed as tables or action algorithms. Epilepsy's pathophysiology is unknown, and so is the cause in some cases. Approval of new antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) rests more on administrative than on clinical criteria. The result of this situation is that scientific evidence remains scarce for all areas of epilepsy. This being the case, 57% of the recommendations in these guidelines stem from consensus between authors and editors and not from scientific evidence. They are therefore expressed as GE-SEN recommendations.

In these guidelines, the terminology and classification systems for ES are those established by the Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy in 1989. This is the dominant practice among the sources we reviewed to create these guidelines.2

These guidelines were shown to be a good reference tool for clinical practice in neurological consults, emergency departments, and primary care centres during 2013.

The full version of this consensus statement can be viewed on the SEN's webpage, and the journal Neurología is publishing excerpts on epilepsy treatment under the following titles:

- -

Emergencies in epilepsy and ES.

- -

Pharmacological treatment of epilepsy (two articles).

- -

Drug-resistant epilepsy. Non-pharmacological treatments.

ES account for about 1% of all emergency department visits. These cases can be categorised as follows3:

- 1.

Patients whose seizure is associated with signs or symptoms of acute, systemic, or CNS disease. This type is known as provoked seizure (PS) (or acute symptomatic seizure), and its treatment requires resolving the underlying cause as well as achieving seizure control.

- 2.

Patients with an initial seizure. The cause of an initial seizure cannot be immediately determined in half of all cases.

- 3.

Patients with known epilepsy who experience worsening of the disorder, referring to both increased critical frequency and increased AED tolerance.

- 4.

Patients with prolonged or clustered seizures that are classified as different types of status epilepticus (SE). Due to their poor prognosis, these conditions require immediate and appropriate treatment.

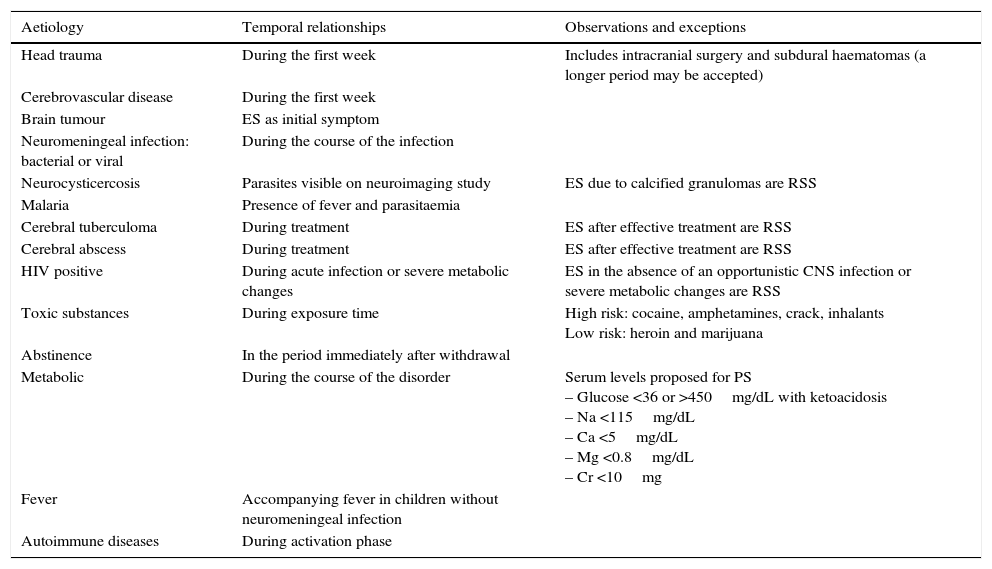

Symptomatic ES are those that arise due to brain insult. There are two types: PS and remote symptomatic seizures (RSS). Provoked or acute symptomatic seizures are those directly caused by, or occurring soon after, a precipitating factor. This factor may be metabolic, toxic, structural, infectious, or inflammatory, and it causes an acute brain event (Table 2). Remote symptomatic ES are caused by pre-existing static or progressive brain lesions. They may appear as isolated events or else recur (epilepsy).

Acute symptomatic epileptic crises

| Aetiology | Temporal relationships | Observations and exceptions |

|---|---|---|

| Head trauma | During the first week | Includes intracranial surgery and subdural haematomas (a longer period may be accepted) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | During the first week | |

| Brain tumour | ES as initial symptom | |

| Neuromeningeal infection: bacterial or viral | During the course of the infection | |

| Neurocysticercosis | Parasites visible on neuroimaging study | ES due to calcified granulomas are RSS |

| Malaria | Presence of fever and parasitaemia | |

| Cerebral tuberculoma | During treatment | ES after effective treatment are RSS |

| Cerebral abscess | During treatment | ES after effective treatment are RSS |

| HIV positive | During acute infection or severe metabolic changes | ES in the absence of an opportunistic CNS infection or severe metabolic changes are RSS |

| Toxic substances | During exposure time | High risk: cocaine, amphetamines, crack, inhalants Low risk: heroin and marijuana |

| Abstinence | In the period immediately after withdrawal | |

| Metabolic | During the course of the disorder | Serum levels proposed for PS – Glucose <36 or >450mg/dL with ketoacidosis – Na <115mg/dL – Ca <5mg/dL – Mg <0.8mg/dL – Cr <10mg |

| Fever | Accompanying fever in children without neuromeningeal infection | |

| Autoimmune diseases | During activation phase |

The current International Classification of Epileptic Syndromes4 places PS among the conditions presenting with ES, but not considered to be epilepsy proper. PS do not require long-term antiepileptic treatment, although short-term treatment may be necessary until the acute condition has resolved.

Scientific evidence for pharmacological treatment of acute symptomatic seizures- -

Carbamazepine, phenobarbital (PB), phenytoin (PHT), and valproic acid (VPA), the classic AEDs, are effective for preventing PS in cases of severe traumatic brain injury. PHT effectively prevents PS after craniotomy.5,6 Level of evidence 1.

- -

Classic AEDs effectively prevent PS due to traumatic brain injury or craniotomy, contrast material, malaria, or alcohol withdrawal syndrome. They do not prevent RSS or future development of epilepsy due to these causes.5,6 Level 1.

- -

Benzodiazepines (BZD) are effective for preventing PS due to alcohol withdrawal.5,6 Level 1.

- -

Patients with brain tumours treated with antineoplastic drugs, radiotherapy, or corticosteroid treatment should not take classic AEDs due to interactions or idiosyncratic adverse effects.6 Level 4.

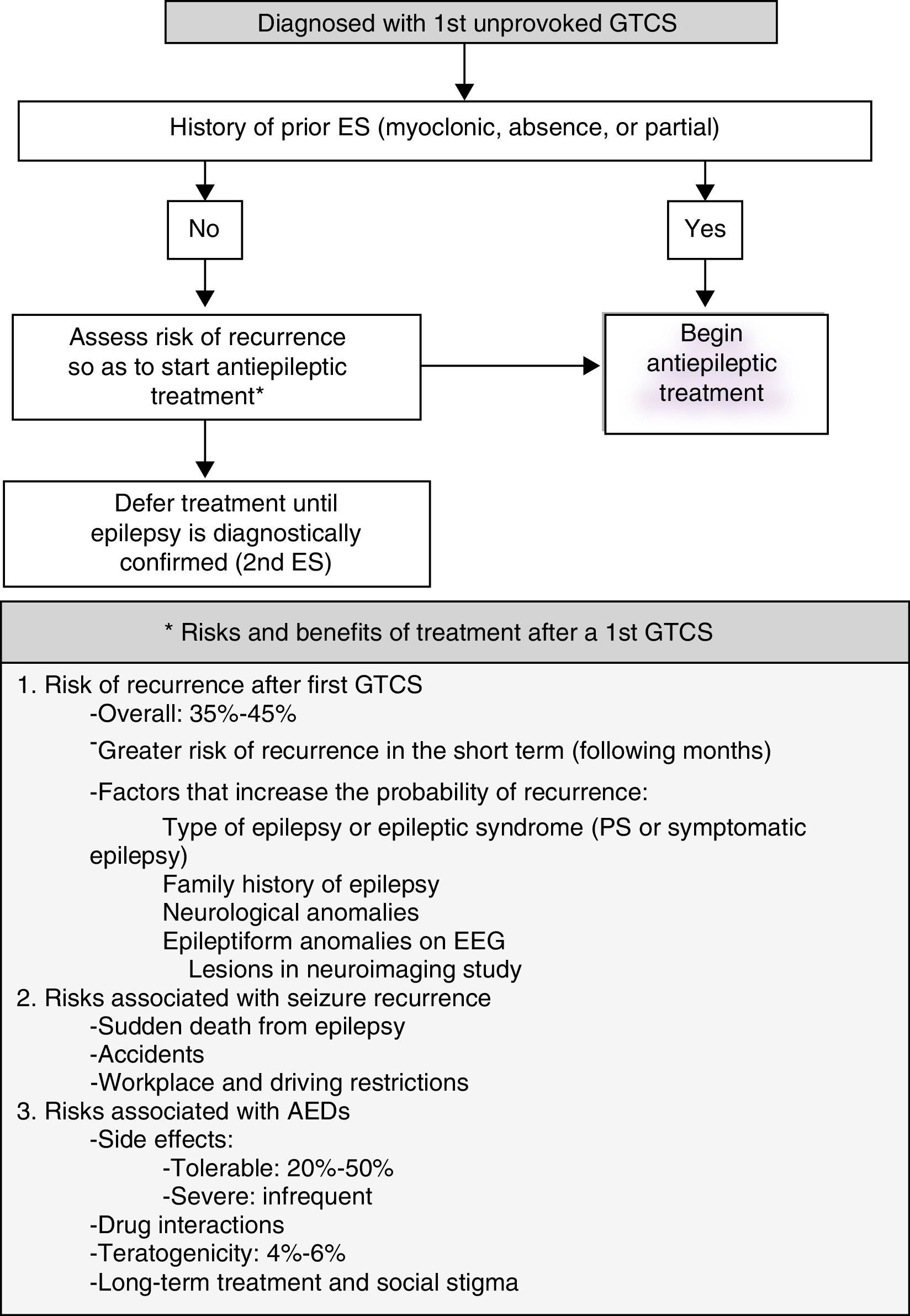

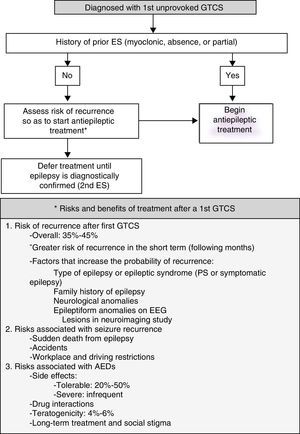

Most patients who visit the emergency department due to ES have experienced an initial generalised tonic-clonic seizure (GTCS) whose cause cannot be determined (Fig. 1).

- -

Most guidelines indicate, based on randomised observational studies, that AED treatment should not be started until the patient experiences a second GTCS of undetermined cause.7 Level 1.

- -

Treatment with AEDs reduces risk of recurrence in the short term (months or weeks), but this does not affect the patient's long-term prognosis for seizure remission.8 Level 1.

Action algorithm for initial GTCS is shown in Fig. 1.

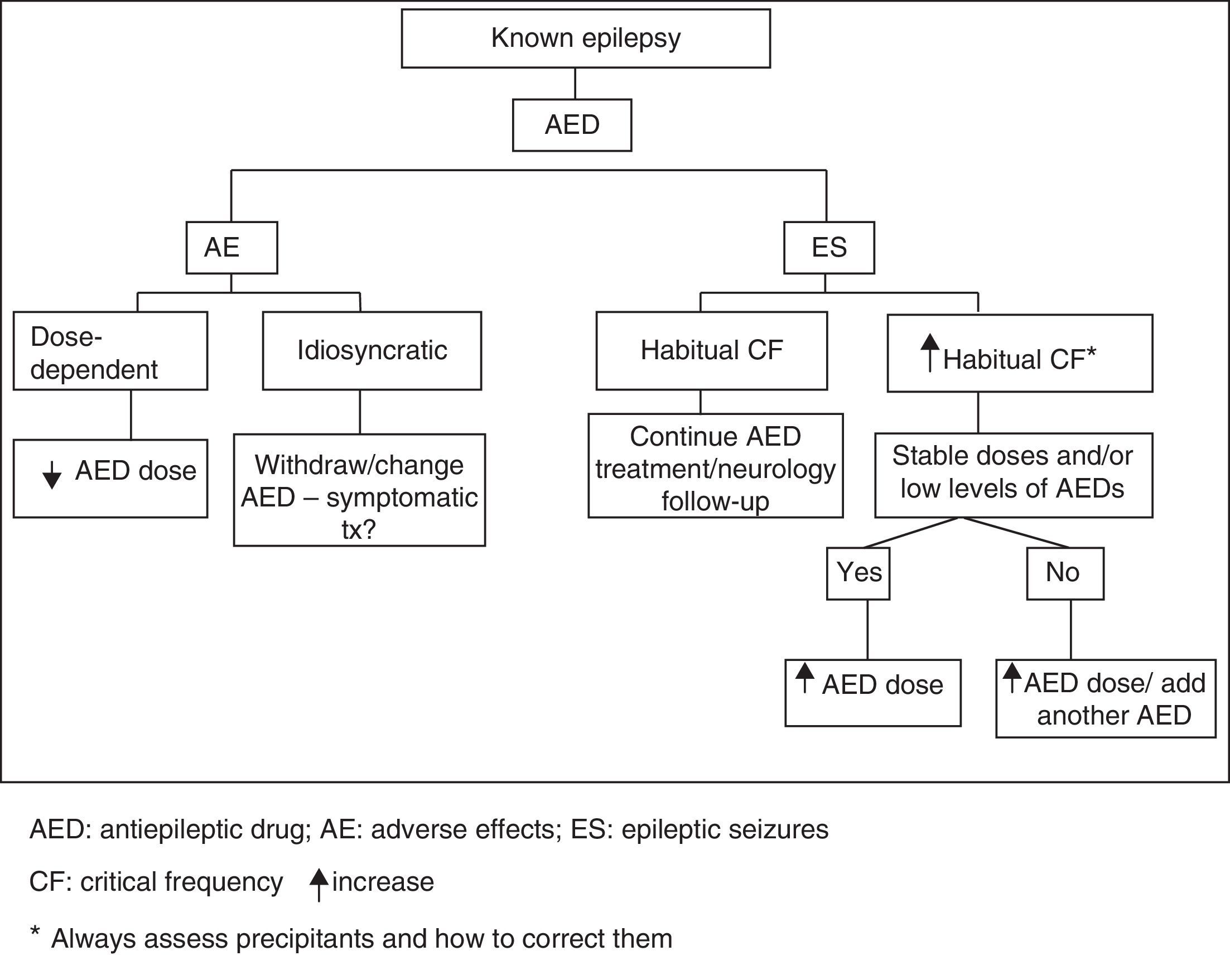

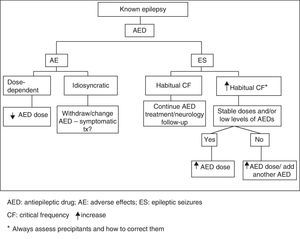

Unfavourable changes in progression of previously diagnosed epilepsy are characterised by either increase in habitual critical frequency or AED intolerance. Emergency action algorithm for this type of clinical situation is shown in Fig. 2.

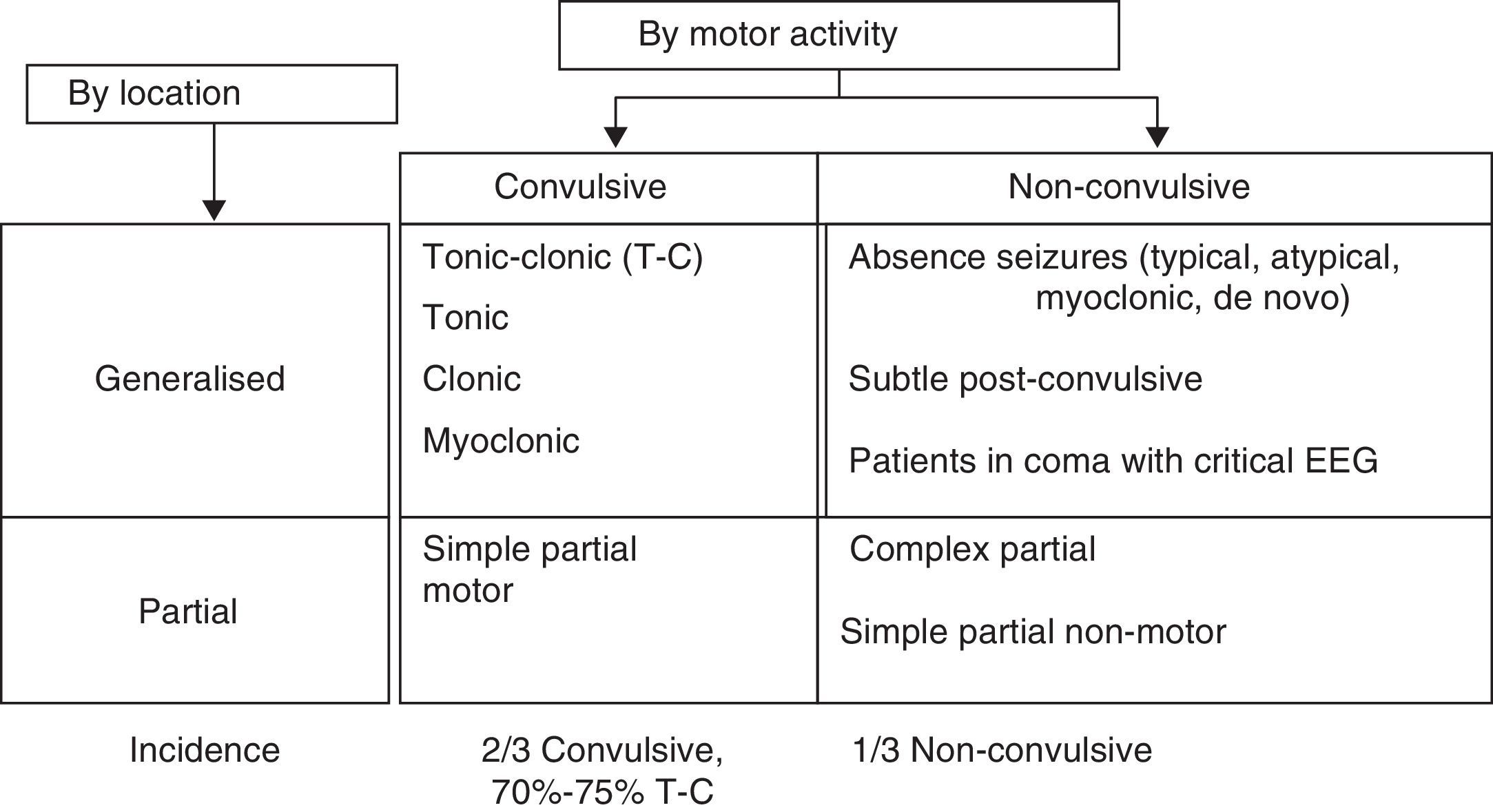

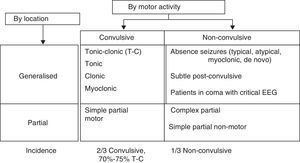

Patients with clustered or prolonged seizures constitute different types of SE. Status epilepticus is a seizure lasting more than 30minutes, or a sequence of seizures repeated over more than 30minutes during which time the patient does not recover the baseline neurological state.9 There are as many types of SE as there are seizure types. The most common classification system for SE is shown in Fig. 3.

Clinical experience and video-EEG monitoring show that a convulsive seizure that continues beyond 5minutes gives rise to convulsive SE. Mortality is higher in cases of SE lasting more than 30minutes.

The literature lists different definitions and classifications of SE for use in clinical practice and treatment.7,10

- •

Convulsive tonic-clonic SE:

- -

A generalised, continuous convulsive seizure lasting 5minutes or longer.

- -

Two or more generalised convulsive seizures presenting without the patient regaining consciousness between seizures.

- -

Cluster seizure: two or more generalised convulsive seizures in an hour.

- -

- •

Refractory SE (RSE): continuous SE after treatment with two appropriately chosen and correctly dosed AEDs.

- •

Non-convulsive SE (NCSE): seizure without recognisable or predominant motor activity and a continuous critical EEG trace. The typical clinical manifestation of this type of SE is decreased level of consciousness.

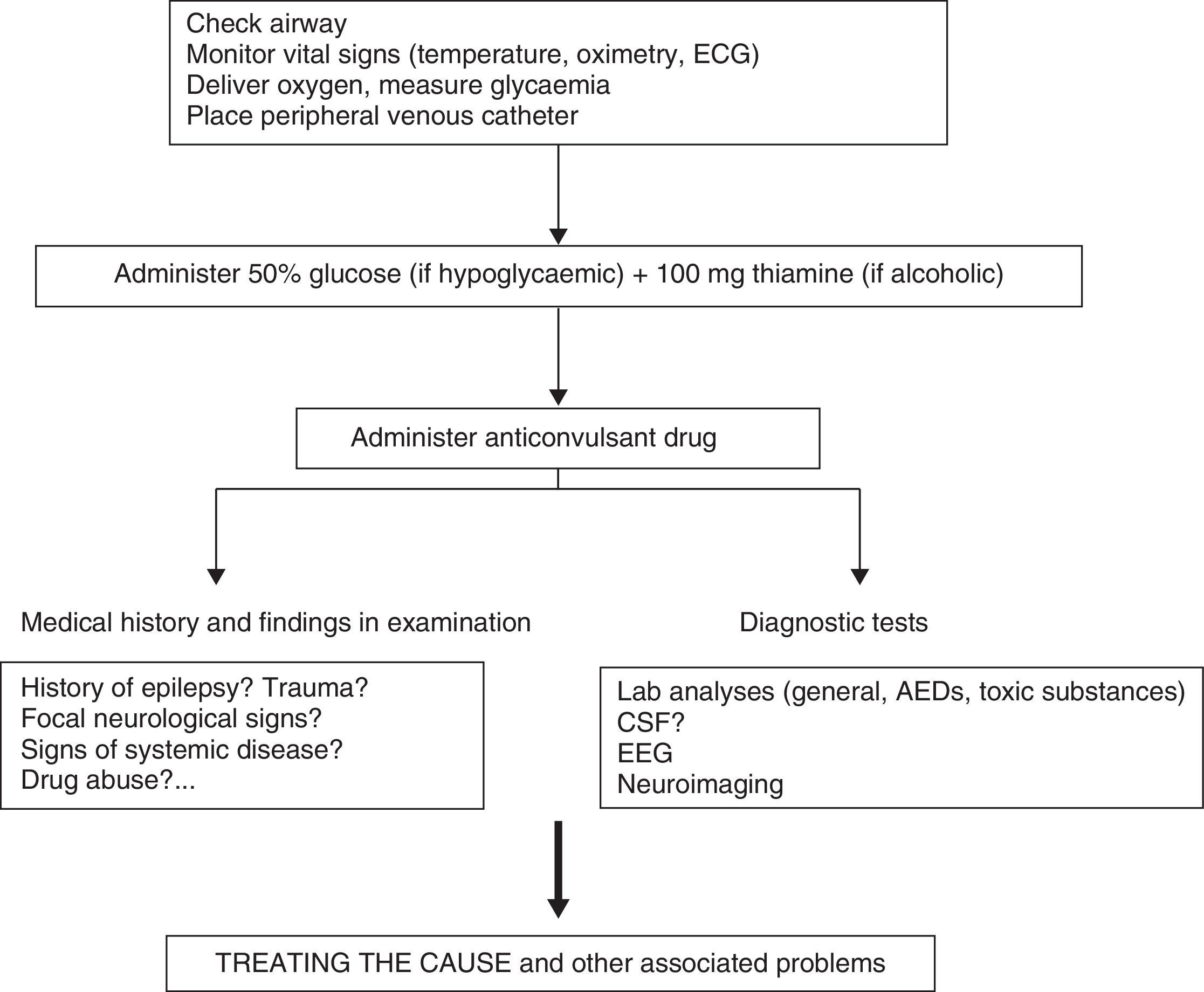

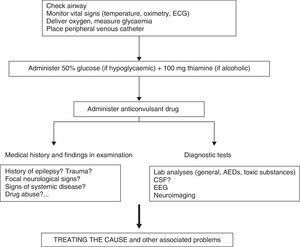

Clinical response to convulsive SE should initially entail checking vital signs, followed by providing anticonvulsant treatment and treating the cause or other associated problems (Fig. 4).

Most CPGs recommend intravenous (IV) administration of the BZD drugs lorazepam (LZP) or diazepam (DZP) as the first line of treatment for all types of SE.7,11

Scientific evidence for initial treatment of convulsive SE- -

LZP and DZP are effective for treating convulsive SE.12 Level 1.

- -

Non-IV midazolam (MDZ, administered by oral, nasal, intramuscular, or rectal routes) is as effective as IV DZP; oral MDZ is superior to rectal DZP.13 Level 2.

- -

Intramuscular MDZ shows similar efficacy to IV LZP as initial prehospital treatment. Level 2.14

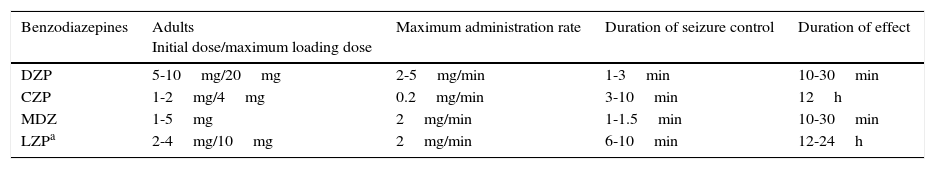

Loading dose, route of administration, and duration of effect vary for different types of BZD (Table 3).

IV treatment regimens and benzodiazepine pharmacokinetics in convulsive SE

| Benzodiazepines | Adults Initial dose/maximum loading dose | Maximum administration rate | Duration of seizure control | Duration of effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DZP | 5-10mg/20mg | 2-5mg/min | 1-3min | 10-30min |

| CZP | 1-2mg/4mg | 0.2mg/min | 3-10min | 12h |

| MDZ | 1-5mg | 2mg/min | 1-1.5min | 10-30min |

| LZPa | 2-4mg/10mg | 2mg/min | 6-10min | 12-24h |

Non-IV treatment regimens: DZP rectal route, 10-30mg; MDZ oral/nasal/intramuscular, 5-10mg.

CZP: clonazepam; DZP: diazepam; LZP: lorazepam; MDZ: midazolam.

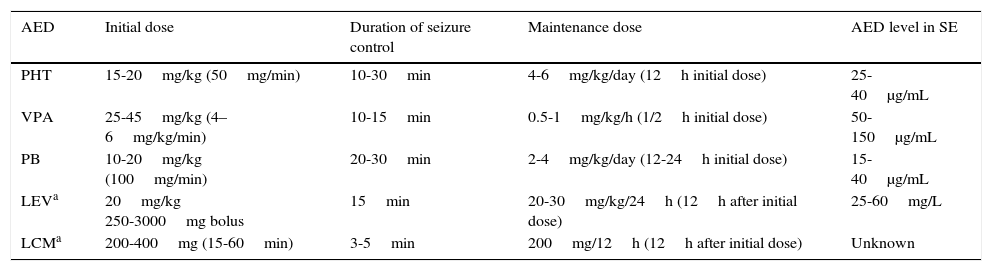

If the initial BZD treatment, including a second dose, fails to control convulsive SE, a second-line AED must be administered (Table 4).

IV treatment regimens and AED pharmacokinetics in convulsive SE

| AED | Initial dose | Duration of seizure control | Maintenance dose | AED level in SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHT | 15-20mg/kg (50mg/min) | 10-30min | 4-6mg/kg/day (12h initial dose) | 25-40μg/mL |

| VPA | 25-45mg/kg (4–6mg/kg/min) | 10-15min | 0.5-1mg/kg/h (1/2h initial dose) | 50-150μg/mL |

| PB | 10-20mg/kg (100mg/min) | 20-30min | 2-4mg/kg/day (12-24h initial dose) | 15-40μg/mL |

| LEVa | 20mg/kg 250-3000mg bolus | 15min | 20-30mg/kg/24h (12h after initial dose) | 25-60mg/L |

| LCMa | 200-400mg (15-60min) | 3-5min | 200mg/12h (12h after initial dose) | Unknown |

AED: antiepileptic drug; LCM: lacosamide; LEV: levetiracetam; PB: phenobarbital; PHT: phenytoin; VPA: valproic acid.

- -

IV DZP+PHT, PB, and LZP are equally effective for controlling convulsive SE at 20minutes after perfusion and during the first hour.12 Level 1.

- -

IV PHT and VPA, and VPA and LEV are equally effective for controlling convulsive SE at 30minutes after perfusion and in cases of adverse effects.10,15 Level 2.

- -

IV lacosamide (LCM) was shown to be effective by different non-prospective, non-controlled studies and case series for different types of SE. Level 4.16

- -

Most CPGs recommend using LZP (4mg IV) or DZP (10mg IV) followed by PHT (18mg/kg IV) or PB (20mg/kg IV).7,11 Level 4.

- -

Treatment with VPA, LEV, or LCM is indicated in cases of RSE or when PHT is contraindicated, as an alternative to IV PB.17,18 Level 3. LEV and LCM are not authorised as treatments for SE.

Several randomised clinical trials are currently being carried out to compare the efficacy of PHT, fosphenytoin, VPA, and LEV.19

Treatment for the cause of seizures, if known, should be administered simultaneously with anticonvulsants. Systemic complications of SE (fever, metabolic disorders, rhabdomyolysis, etc.) should also be treated at the same time (Table 5).

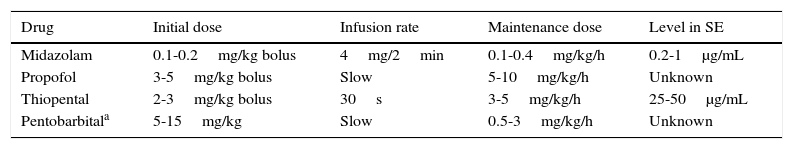

Instructions for IV treatment and pharmacokinetics for anaesthetics as treatment for convulsive SE

| Drug | Initial dose | Infusion rate | Maintenance dose | Level in SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Midazolam | 0.1-0.2mg/kg bolus | 4mg/2min | 0.1-0.4mg/kg/h | 0.2-1μg/mL |

| Propofol | 3-5mg/kg bolus | Slow | 5-10mg/kg/h | Unknown |

| Thiopental | 2-3mg/kg bolus | 30s | 3-5mg/kg/h | 25-50μg/mL |

| Pentobarbitala | 5-15mg/kg | Slow | 0.5-3mg/kg/h | Unknown |

There is no consensus on a definition of RSE. The medical literature defines RSE as a seizure lasting more than 60minutes, or failure of two appropriately employed and properly dosed second-line AEDs.

Steps in treating RSE are as follows:

- 1.

Admit patient to the ICU. Stabilise vital signs. Continue treating or investigating the cause.

- 2.

Maintain treatment with habitual AEDs.

- 3.

Induce medical coma during 24 to 48hours. There is no evidence that barbiturates (thiopental) are superior to non-barbiturates (propofol, MDZ) for inducing a medical coma.10,11,20 Level 4. The choice of treatment depends on associated comorbidities, pharmacokinetics, and adverse effects.

- 4.

Withdraw drugs used to induce coma in 12 to 24hours if clinical symptoms and EEG indicate SE resolution (monitoring).

- 5.

Start/continue administering long-term AED treatment.

- 6.

Treat cause and any complications.

If RSE persists after 24hours of starting anaesthetic treatment, or if SE recurs with reduction or withdrawal of anaesthesia (a clinical state called ‘super-refractory’ SE by some authors), other types of non-anaesthetic treatment should be attempted. These include magnesium sulphate, pyridoxine (in children), steroids, immunoglobulins, plasmapheresis, hypothermia, ketogenic diet, electroconvulsive therapy, neurosurgery for lesion-induced SE, and vagus nerve stimulation; treatment sequences vary depending on the cause and according to different authors.20 Level 4.

NCSEThis definition is based on absence of manifest motor activity with an indicative EEG pattern. If there is a clinical suspicion, the diagnosis is confirmed by EEG. Lack of unified EEG terminology makes it more difficult to classify cases of NCSE.

Most authors use electroclinical data to classify NCSE into two groups: with and without coma/stupor.

The group without coma/stupor is further subdivided into SE with generalised onset (absence SE: typical, atypical, or myoclonic), focal onset (NCSE with or without altered consciousness, aphasia, etc.), and unknown origin (autonomic NCSE).21

There is no high-level evidence regarding which treatment to choose for each type.

For non-hospitalised patients with a prolonged history of confusional states, experts recommend treatment with BZD, preferably by the oral route.7

Treatment for patients in coma following a convulsive SE episode (subtle NCSE) resembles that for RSE cases. Critical activity can be seen on the EEG trace in 20% to 30% of the cases in which the patient is comatose and his/her situation is critical due to a wide range of serious causes (anoxic brain injury after cardiac arrest, head trauma, severe intoxication, etc.). The underlying cause, which determines prognosis, has to be treated in these cases, and non-sedating AEDs must be added to the treatment regimen.12

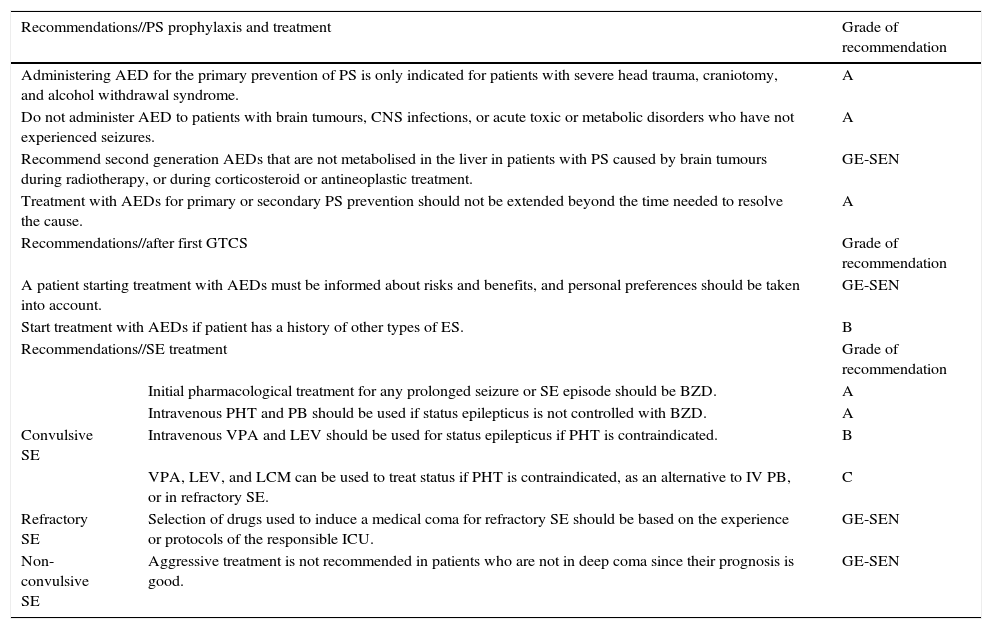

We have listed recommendations for a variety of clinical situations that may be observed in the emergency department (Table 6).

General list of recommendations for treating epilepsy in the emergency department

| Recommendations//PS prophylaxis and treatment | Grade of recommendation | |

|---|---|---|

| Administering AED for the primary prevention of PS is only indicated for patients with severe head trauma, craniotomy, and alcohol withdrawal syndrome. | A | |

| Do not administer AED to patients with brain tumours, CNS infections, or acute toxic or metabolic disorders who have not experienced seizures. | A | |

| Recommend second generation AEDs that are not metabolised in the liver in patients with PS caused by brain tumours during radiotherapy, or during corticosteroid or antineoplastic treatment. | GE-SEN | |

| Treatment with AEDs for primary or secondary PS prevention should not be extended beyond the time needed to resolve the cause. | A | |

| Recommendations//after first GTCS | Grade of recommendation | |

| A patient starting treatment with AEDs must be informed about risks and benefits, and personal preferences should be taken into account. | GE-SEN | |

| Start treatment with AEDs if patient has a history of other types of ES. | B | |

| Recommendations//SE treatment | Grade of recommendation | |

| Initial pharmacological treatment for any prolonged seizure or SE episode should be BZD. | A | |

| Intravenous PHT and PB should be used if status epilepticus is not controlled with BZD. | A | |

| Convulsive SE | Intravenous VPA and LEV should be used for status epilepticus if PHT is contraindicated. | B |

| VPA, LEV, and LCM can be used to treat status if PHT is contraindicated, as an alternative to IV PB, or in refractory SE. | C | |

| Refractory SE | Selection of drugs used to induce a medical coma for refractory SE should be based on the experience or protocols of the responsible ICU. | GE-SEN |

| Non-convulsive SE | Aggressive treatment is not recommended in patients who are not in deep coma since their prognosis is good. | GE-SEN |

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Mercadé Cerdá JM, Toledo Argani M, Mauri Llerda JA, López Gonzalez FJ, Salas Puig X, Sancho Rieger J. Guía oficial de la Sociedad Española de Neurología de práctica clínica en epilepsia. Neurología. 2016;31:121–129.