The COVID-19 pandemic has caused an unexpected boost to telemedicine. We analyse the impact of the pandemic on telemedicine applied in Spanish headache consultations, review the literature, and issue recommendations for the implementation of telemedicine in consultations.

MethodThe study comprised 3 phases: 1) review of the MEDLINE database since 1958 (first reported experience with telemedicine); 2) Google Forms survey sent to all members of the Spanish Society of Neurology’s Headache Study Group (GECSEN); and 3) online consensus of GECSEN experts to issue recommendations for the implementation of telemedicine in Spain.

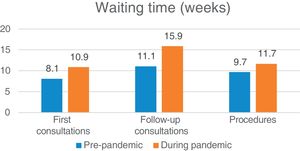

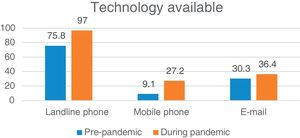

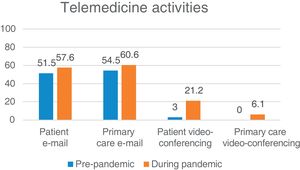

ResultsCOVID-19 has increased waiting times for face-to-face consultations, increasing the use of all telemedicine modalities: landline telephone (from 75% before April 2020 to 97% after), mobile telephone (from 9% to 27%), e-mail (from 30% to 36%), and video consultation (from 3% to 21%). Neurologists are aware of the need to expand the availability of video consultations, which are clearly growing, and other e-health and m-health tools.

ConclusionsThe GECSEN recommends and encourages all neurologists who assist patients with headaches to implement telemedicine resources, with the optimal objective of offering video consultation to patients under 60-65 years of age and telephone calls to older patients, although each case must be considered on an individual basis. Prior approval and advice must be sought from legal and IT services and the centre’s management. Most patients with stable headache and/or neuralgia are eligible for telemedicine follow-up, after a first consultation that must always be held in person.

La pandemia COVID-19 ha provocado un inusitado impulso a la Telemedicina (TM). Analizamos el impacto de la pandemia en la TM aplicada en las consultas de cefaleas españolas, revisamos la literatura y lanzamos unas recomendaciones para implantar la TM en las consultas.

MétodoTres fases: 1) Revisión de la base Medline desde el año 1958 (primera experienciade TM); 2) Formulario Google Forms enviado a todos los neurólogos del Grupo de Estudio de Cefaleas de la Sociedad Espa˜nola de Neurología (GECSEN), y 3) Consenso on-line de expertos GECSEN para emitir recomendaciones para implantar la TM en. España.

ResultadosLa pandemia por COVID-19 ha empeorado los tiempos de espera presenciales, incrementando el uso de todas las modalidades de TM antes y después de abril de 2020: teléfono fijo (del 75% al 97%), teléfono móvil (del 9% al 27%), correo electrónico (del 30% al 36%), y videoconsulta (del 3% al 21%). Los neurólogos son conscientes de la necesidad de ampliar la oferta con videoconsultas, claramente in crescendo, y otras herramientas de e-health y m-health.

ConclusionesDesde el GECSEN recomendamos y animamos a todos los neurólogos que asisten a pacientes con cefaleas a implantar recursos de TM, teniendo como objetivo óptimo la videoconsulta en menores de 60-65 años y la llamada telefónica en mayores, si bien cada caso debe individualizarse. Se deberá contar previamente con la aprobación y asesoramiento de los servicios jurídicos e informáticos y de la dirección del centro. La mayoría de los pacientes con cefalea y/o neuralgia estable son candidatos a seguimiento mediante TM, tras una primera visita que tiene que ser siempre presencial.

Telemedicine (TM) is not as novel as is widely believed, as it first emerged with the creation of the telegraph, radio, and telephone. Though it was used sporadically during the First World War, the first public experience of TM as it is known today was in 2 states during the New York World’s Fair in 1951. The first therapeutic experience was conducted by the psychiatrist Cecil Wittson in 1958, with the implementation of a distance education and telepsychiatry programme using closed-circuit television at the Nebraska Psychiatric Institute,1 which he directed (Fig. 1).

Left: a therapy session held over closed-circuit television at the Nebraska Psychiatric Institute in the late 1950s.1 Right: a neurologist at Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau in Barcelona holding a video-consultation, using the desktop computer at her consultation to connect to the smartphone of a patient with migraine (June 2020).

Since then, the concept of TM has evolved in line with developments in information and communication technology (ICT), advancing greatly with the emergence of the Internet and once more with the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic completely changed our clinical practice; TM has taken a central role and is now being used alongside traditional in-person medicine (Fig. 1).

This new approach in patient assessment cannot compete with in-person clinical interviews with patients with headache, and will never replace neurological examination. However, TM will become increasingly important, and its integration in daily practice must be managed appropriately.

In the light of this, the Spanish Society of Neurology’s Headache Study Group (GECSEN, for its Spanish initials), in collaboration with the Spanish Society of Neurological Nursing (SEDENE) and the Spanish Society of Neurology’s Ad-hoc Committee on New Technologies and Innovation (TecnoSEN), drafted this consensus statement, which we hope may serve as guidance for all neurologists attending patients with headache disorders and neuralgias. The statement reviews important issues such as the concepts of TM and teleneurology, the relevant legislation, and the advantages and disadvantages of this approach. Finally, we present data on the current situation of TM in public headache units and clinics, and issue a series of recommendations to optimise our adaptation to this new form of medical consultation and to ensure that patients receive quality care.

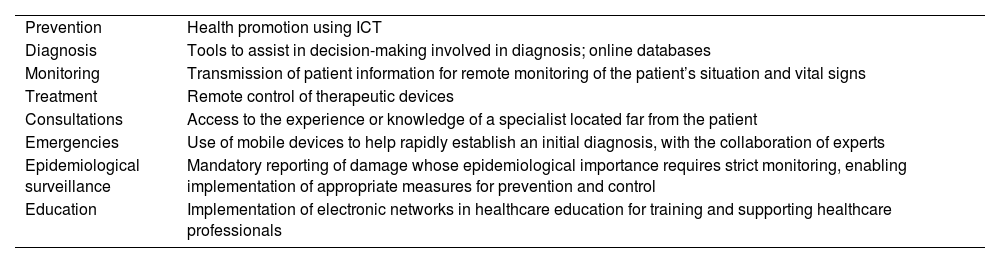

What is telemedicine? Strategies, models, platforms, and current applicationsTM is defined as the use of ICT for the remote exchange of information in healthcare provision and education through teleconsultations. It is defined by the World Health Organization as “the delivery of healthcare services where distance is a critical factor, by all healthcare professionals using information and communication technologies for the exchange of valid information for diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease and injuries all in the interests of advancing the health of individuals and their communities.” Applications of TM are listed in Table 1, and essentially focus on prevention, diagnosis, monitoring, treatment, consultation, emergencies, epidemiological surveillance, medical instruction, healthcare education (tele-education), and research (assessment in clinical trials), among others.

Current applications of telemedicine.

| Prevention | Health promotion using ICT |

| Diagnosis | Tools to assist in decision-making involved in diagnosis; online databases |

| Monitoring | Transmission of patient information for remote monitoring of the patient’s situation and vital signs |

| Treatment | Remote control of therapeutic devices |

| Consultations | Access to the experience or knowledge of a specialist located far from the patient |

| Emergencies | Use of mobile devices to help rapidly establish an initial diagnosis, with the collaboration of experts |

| Epidemiological surveillance | Mandatory reporting of damage whose epidemiological importance requires strict monitoring, enabling implementation of appropriate measures for prevention and control |

| Education | Implementation of electronic networks in healthcare education for training and supporting healthcare professionals |

ICT: information and communication technology.

TM offers neurologists the ability to assess patients remotely, unhindered by distance or barriers to access. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Spanish healthcare system was equipped to provide at-home TM on a small scale. Three in 4 hospitals in the United States were using TM before the pandemic, although most patients were attended in person.2 However, in the context of the pandemic, TM has become an everyday tool to improve access to care and to minimise the risk of person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection.3,4

A retrospective analysis of a cohort of 50 185 patients found that TM support in primary care reduced specialist consultation times and the number of patients on waiting lists, enabling patients with more severe illness to see specialists earlier5; the use of TM has also resulted in improvements in referral systems.6 Furthermore, 25%-70% of patients referred to specialist consultations did not require an in-person appointment,7 demonstrating the great value of TM in avoiding unnecessary diagnostic tests and procedures.8 TM and its numerous applications require proper training of healthcare staff, and must observe the regulations and legislation in force in each country or supranational organisation.9

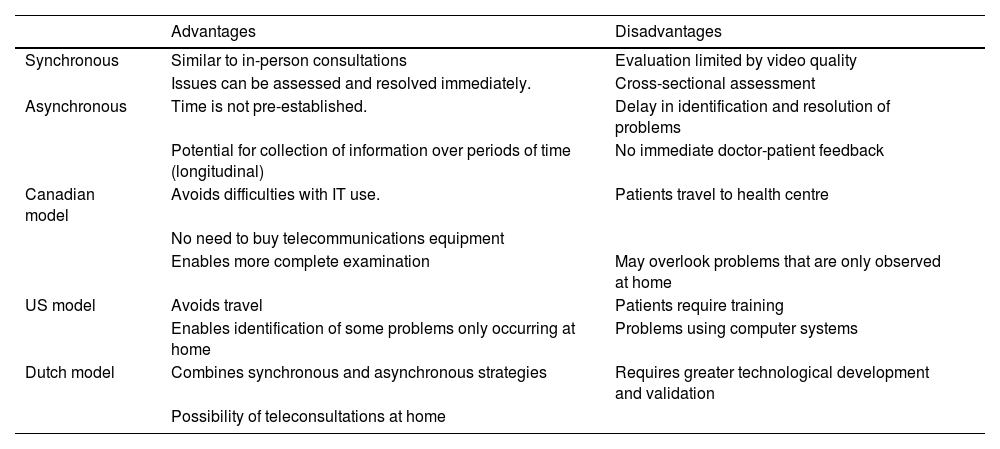

Telemedicine strategies and models. The application of TM in the field of neurology is known as teleneurology, and may follow 2 basic approaches: synchronous and asynchronous strategies. Furthermore, various models may be implemented, depending on where consultations are held and whether an intermediary is present (Table 2). Teleneurology care may also follow a multidisciplinary approach involving several medical specialists or teams, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and other professionals, further improving care quality.

Main characteristics of telemedicine models and strategies.

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|

| Synchronous | Similar to in-person consultations | Evaluation limited by video quality |

| Issues can be assessed and resolved immediately. | Cross-sectional assessment | |

| Asynchronous | Time is not pre-established. | Delay in identification and resolution of problems |

| Potential for collection of information over periods of time (longitudinal) | No immediate doctor-patient feedback | |

| Canadian model | Avoids difficulties with IT use. | Patients travel to health centre |

| No need to buy telecommunications equipment | ||

| Enables more complete examination | May overlook problems that are only observed at home | |

| US model | Avoids travel | Patients require training |

| Enables identification of some problems only occurring at home | Problems using computer systems | |

| Dutch model | Combines synchronous and asynchronous strategies | Requires greater technological development and validation |

| Possibility of teleconsultations at home |

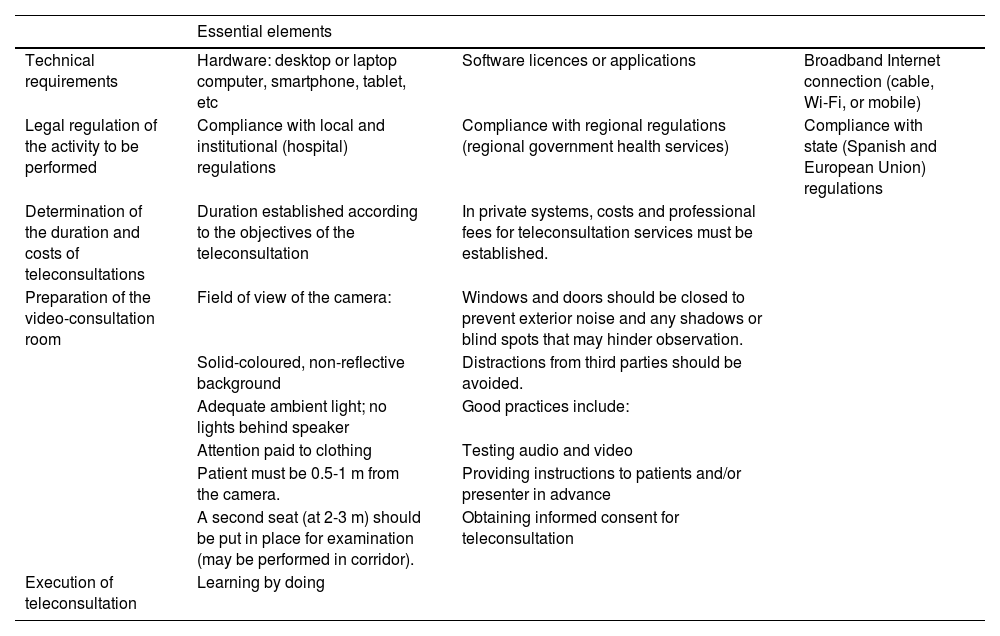

The recommendations for the implementation of such systems are summarised in Table 3. These recommendations were issued in the manual on the use of new technologies in movement disorders published by the Spanish Society of Neurology’s Movement Disorders Study Group.10

Recommendations for implementing teleconsultation.

| Essential elements | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Technical requirements | Hardware: desktop or laptop computer, smartphone, tablet, etc | Software licences or applications | Broadband Internet connection (cable, Wi-Fi, or mobile) |

| Legal regulation of the activity to be performed | Compliance with local and institutional (hospital) regulations | Compliance with regional regulations (regional government health services) | Compliance with state (Spanish and European Union) regulations |

| Determination of the duration and costs of teleconsultations | Duration established according to the objectives of the teleconsultation | In private systems, costs and professional fees for teleconsultation services must be established. | |

| Preparation of the video-consultation room | Field of view of the camera: | Windows and doors should be closed to prevent exterior noise and any shadows or blind spots that may hinder observation. | |

| Solid-coloured, non-reflective background | Distractions from third parties should be avoided. | ||

| Adequate ambient light; no lights behind speaker | Good practices include: | ||

| Attention paid to clothing | Testing audio and video | ||

| Patient must be 0.5-1 m from the camera. | Providing instructions to patients and/or presenter in advance | ||

| A second seat (at 2-3 m) should be put in place for examination (may be performed in corridor). | Obtaining informed consent for teleconsultation | ||

| Execution of teleconsultation | Learning by doing | ||

Platforms and current applications. Several platforms have been developed for the dissemination, collection, and processing of data, as well as numerous teleconferencing programs and services.11,12 Whatever the information system and communication interface used in a specific setting, for example in a hospital network, it is essential to ensure adequate standards of encryption, security, and privacy in compliance with the data protection standards in force. Such widely used tools as Telegram, WhatsApp, and FaceTime (iOS) provide end-to-end encryption, although their use in TM is not currently regulated.

Telemedicine implementation before and after the COVID-19 pandemicThe continuous progress in ICT, and especially the widespread use of smartphones and remote patient monitoring systems, has led to considerable advances in TM. However, in our setting, in-person consultations were the norm before the COVID-19 pandemic, and the use of TM was restricted to the evaluation of radiology images, anatomical pathology samples, and skin lesions.13

Today, it is possible to take medical history using video-conferencing, to monitor vital signs using mobile applications, and even to view complementary examinations, such as electrocardiography recording.

The primary objective of TM is to improve access to healthcare. It also facilitates communication and the exchange of information between community healthcare professionals and specialists at university hospitals.14 To this end, programs have been developed to provide timely, accurate, specialised information at the time and place it is most needed, for instance in teletrauma, telestroke, and teleradiology.15 Furthermore, in parallel with the development of minimally invasive surgery, telesurgery using remotely operated robotic surgical systems enables surgeons to provide expert care in remote locations.16

Optimising the treatment of patients with chronic diseases is another objective of TM, which may improve treatment adherence through the use of applications or reminders and/or enhance education or non-pharmacological therapies that are often underfunded in healthcare systems, such as rehabilitation or psychotherapy.15 The development of sensors for home monitoring of vital signs, glycaemia, or electrocardiography readings, among other parameters, and associated alarm systems has enabled remote monitoring in real time to help predict exacerbations of chronic diseases requiring rapid attention.17,18

TM has enabled screening of patients with suspected COVID-19 through monitoring of respiratory symptoms and triage prior to assessment in the emergency department, particularly in high-risk groups. Due to the inability to perform a physical examination, patients take their temperature at home and speak with physicians over video-conference for assessment of their general status and breathing, and for oropharyngeal examination.19

During the pandemic, practically all medical specialties were forced to rely on technology to continue attending their patients, with psychiatry, oncology, gynaecology, and dermatology being key examples.20

However, the generalised use of TM has significant limitations related to some patients’ and healthcare professionals’ lack of knowledge and trust in these tools, problems associated with the exchange of confidential information, and the need to create reimbursement systems for TM services.13,21 The American College of Physicians considers TM to be a useful strategy for healthcare provision, and issues a series of recommendations. It considers TM to be more effective when an established, continuing doctor-patient relationship already exists, and in patients in whom physical examination is not essential. Furthermore, the recommendations also highlight the need for clinical guidelines on the provision of this type of care.21

Teleneurology and its application in headache clinicsA considerable percentage of patients attended at neurology departments have chronic diseases; in-person consultations with these patients were reduced to a minimum during the pandemic to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2. As a result, TM became a reliable, satisfactory tool for neurological care,4,21 as demonstrated by various studies reporting experiences in the fields of dementia,22–24 epilepsy,25,26 movement disorders,27 multiple sclerosis,28 and neuromuscular diseases.29

However, although headache is the most frequent reason for consultation at Spanish neurology departments, little attention has been placed on TM in this context, with only 3 embryonic studies having been published. These articles describe online consultations for second opinions or virtual consultation between the neurologist, at hospital, and the patient, at their primary care centre, using the family doctor’s desktop computer.30–33

TM is clearly useful in certain cases in the diagnosis and treatment of uncomplicated headaches, and for reducing waiting lists and healthcare expenditure.23 Furthermore, the second edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders has been validated for the diagnosis of migraine through telephone interviews.34

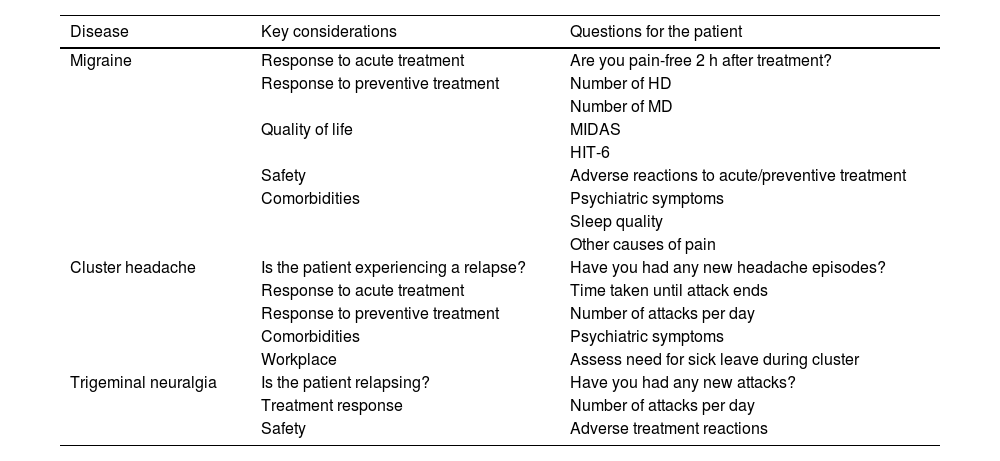

Despite this, generalised use of TM may be hindered by the need for appropriate equipment and the increase in interventional techniques; therefore, there is a need to optimise TM approaches.35 In general, with respect to the 3 most common patient profiles in headache clinics, me may ask a series of basic questions that should be addressed in history-taking (Table 4).

Basic issues to address in telephone interviews.

| Disease | Key considerations | Questions for the patient |

|---|---|---|

| Migraine | Response to acute treatment | Are you pain-free 2 h after treatment? |

| Response to preventive treatment | Number of HD | |

| Number of MD | ||

| Quality of life | MIDAS | |

| HIT-6 | ||

| Safety | Adverse reactions to acute/preventive treatment | |

| Comorbidities | Psychiatric symptoms | |

| Sleep quality | ||

| Other causes of pain | ||

| Cluster headache | Is the patient experiencing a relapse? | Have you had any new headache episodes? |

| Response to acute treatment | Time taken until attack ends | |

| Response to preventive treatment | Number of attacks per day | |

| Comorbidities | Psychiatric symptoms | |

| Workplace | Assess need for sick leave during cluster | |

| Trigeminal neuralgia | Is the patient relapsing? | Have you had any new attacks? |

| Treatment response | Number of attacks per day | |

| Safety | Adverse treatment reactions |

HD: headache days per month; HIT-6: Headache Impact Test-6; MD: migraine days per month; MIDAS: Migraine Disability Scale.

The nursing profession is adapting to provide care to patients who are increasingly accustomed to using technology; incorporating innovative TM tools is a key element in the management of patients diagnosed with headache.36 Despite the complexity of this, we propose 2 basic pillars in this work:

Firstly, healthcare education addressing both the disease and its treatment. Regardless of the field in which this support is provided, the short-term objective should be patient empowerment. The long-term objective should be to improve quality of life and adherence to pharmacological treatment.

The incorporation of anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies as a preventive treatment for migraine seems unlikely to constitute a limitation on the use of TM, both by nurses and by patients, as adverse reactions to these drugs are infrequent and mild. However, due to their parenteral administration route, it currently seems challenging to start administering these types of treatments through TM alone, although, broadly speaking, patients receiving them could be followed up by trained nurses using TM, which would most probably reduce workloads at headache clinics.

Without a doubt, nurses using TM will provide effective, efficient care to patients with headache.

Current situation of telemedicine in headache careTo support these recommendations, we sought to establish the current situation of TM in headache care in Spain. A questionnaire was distributed to the directors of headache units/clinics, with questions divided into 4 sections:

Section 1. Characteristics of the unit/clinic. This section enquired about whether the respondent worked at a headache unit or headache clinic; about the population of the reference area; and other characteristics relevant to the care provided. It also addressed the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic on waiting times.

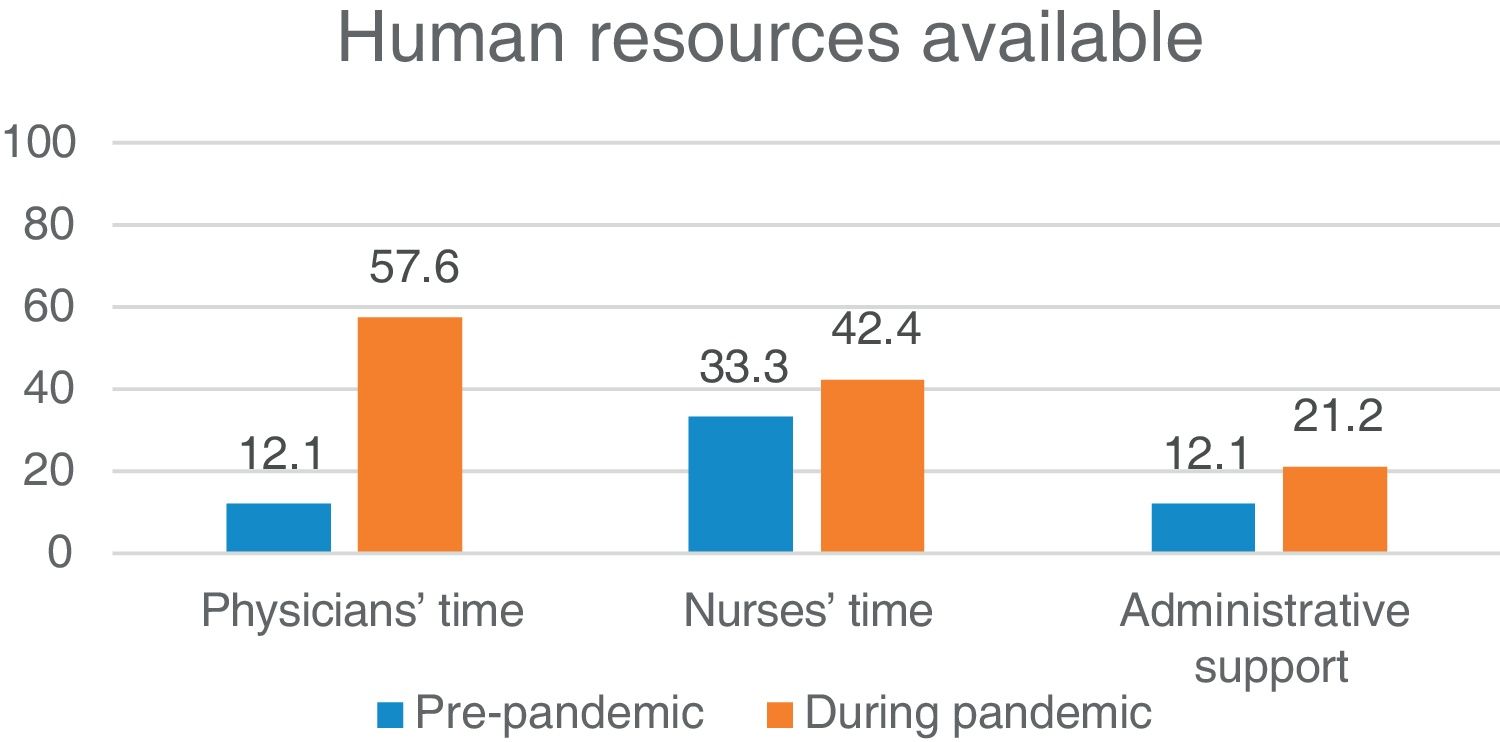

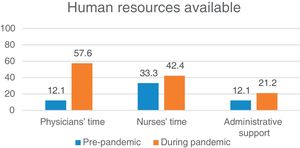

Section 2. Human resources available for TM before and during the pandemic, such as time allotted in neurologists’ or nurses’ schedules and the availability of administrative support staff. The final question addressed respondents’ highest-priority human resources needs for the provision of TM care at their unit/clinic.

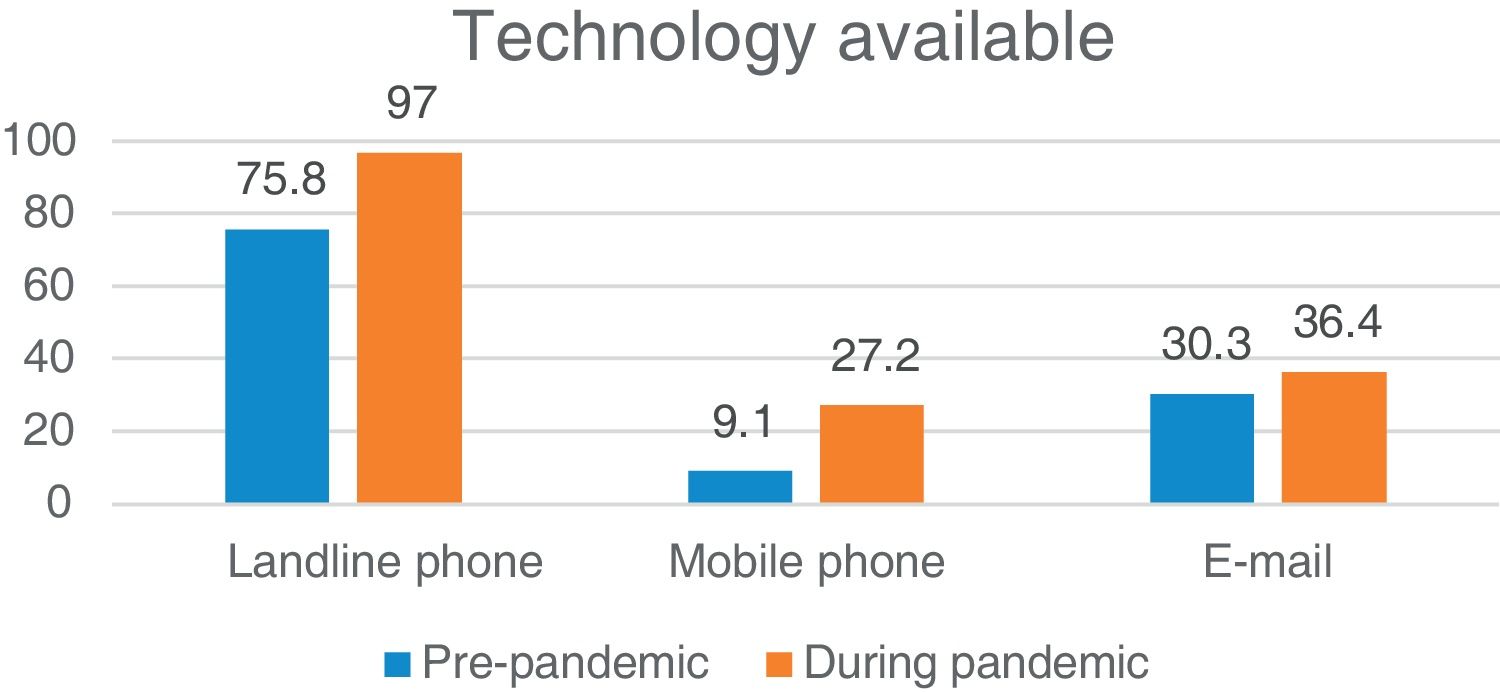

Section 3. Technological resources available for TM provision, such as landline or mobile phones, hardware/software, e-mail, and applications. As in the previous section, we enquired about changes related to the pandemic and the highest-priority needs in this area.

Section 4. TM activities available at the headache unit/clinic, both before and after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. The final question in this section addressed respondents’ priorities for the implementation of new activities.

The survey was sent to the directors of all 65 headache units and clinics belonging to GECSEN, with an initial e-mail inviting them to participate and a subsequent reminder e-mail. The questionnaire, created with Google Forms, was available between 22 October and 10 November 2020. We received 33 responses (50.7%) from neurologists working in 13 of the 17 Spanish Autonomous Communities; the best represented regions were Madrid and Catalonia, with 6 responses from each.

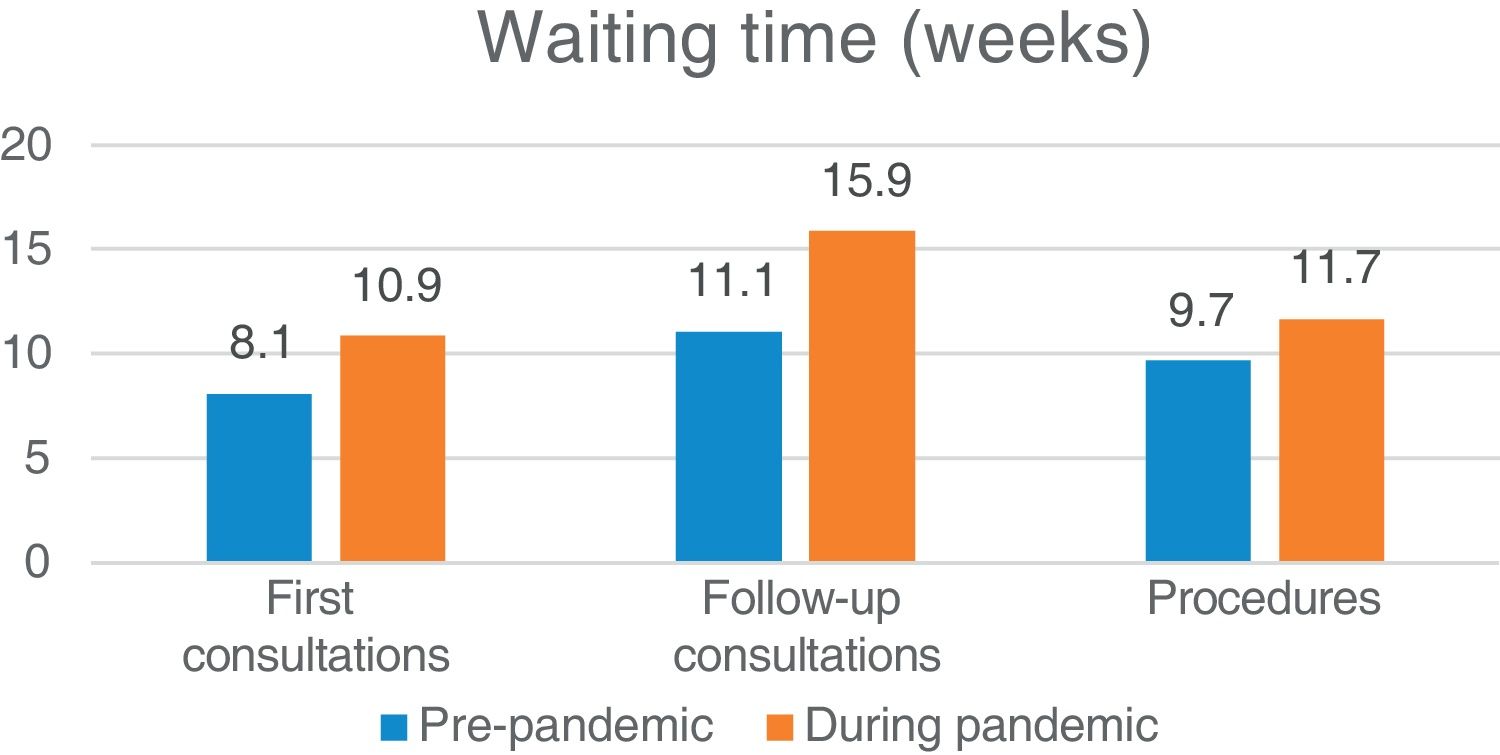

A total of 36.3% of respondents worked at headache units, with the rest working at specialised headache clinics; 57.6% of clinics/units received referrals from other healthcare districts. Clinics/units held a mean of 3.4 (range, 1-13) consultation sessions per week, with 557 (120-1580) first consultations and 1844 (480-10 000) follow-up consultations per year. Fig. 2 summarises the effect of the pandemic on waiting lists.

Fig. 3 shows the availability of specific time allotted to TM in physicians’ and nurses’ schedules, and the presence of administrative support, before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Respondents were also asked about their greatest needs in terms of human resources to maintain or broaden TM provision. The need for more neurologists was mentioned by 42.4% of respondents, with 27.3% reporting that they needed more nurses and 21.2% describing a need for administrative support staff.

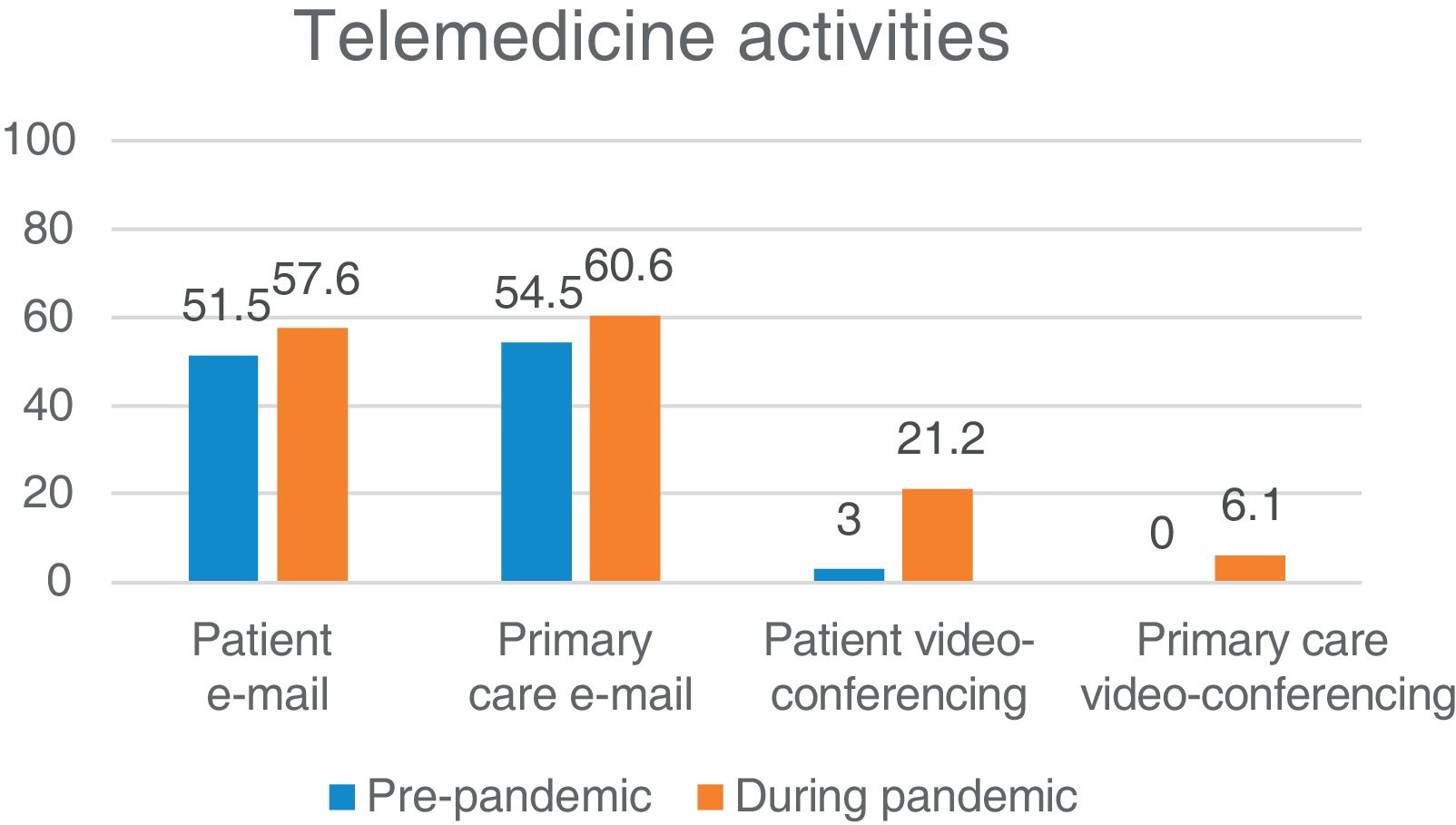

Regarding the technology available for TM provision, telephone and e-mail were the main resources mentioned. Respondents reported greater availability of landline phones with external lines and mobile phones during the pandemic, as well as institutional e-mail at the unit/clinic. These results are shown in Fig. 4. No changes were reported during the pandemic in the availability of such other resources as an Internet connection at the hospital (42.4%) or a specific router at the headache clinic/unit (30.3%). Responses were heterogeneous with regard to the greatest technological needs, with Wi-Fi connections, mobile phones, and video-conferencing devices being the most frequent. Several respondents reported that they needed more time; thus, human resources were considered more important than technological resources.

The final section of the survey addressed the TM activities available at each unit/clinic. Fig. 5 shows the availability of e-mail and video-conferencing consultations for patients and primary care physicians, before and during the pandemic. Three centres implemented systems for SMS and WhatsApp communication between nurses and patients; another centre developed an m-health (mobile health) system for patient follow-up. Finally, 45.4% of respondents considered video-consultations with patients the greatest priority for the future implementation of TM activities at their centres.

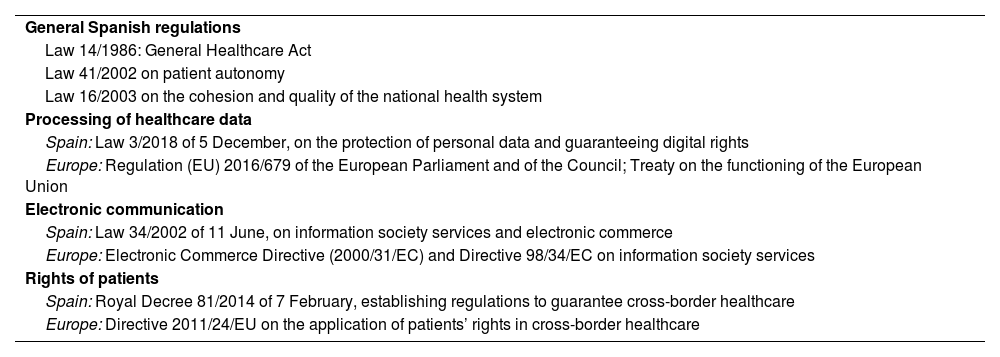

Telemedicine regulations and legislationOne of the factors that has most delayed the implementation, validation, and consolidation of several TM modalities is the lack of a specific regulatory framework. This need for regulation has prevented the application of many forms of TM that have been technically feasible for 20 years or longer. Furthermore, this lack of regulation has habitually been used by government to justify such delays, with privacy and security concerns having been raised even within the medical profession, which has historically resisted change, citing the sanctity of the doctor-patient relationship, the art of medicine, and other romantic ideals. However, we have been using telephones (a form of TM) all our lives to speak with patients, their relatives, and other physicians, and nobody has ever thought to regulate this practice. It took a pandemic to turn this situation around, with TM becoming an urgently needed, essential strategic tool overnight.10

Unlike other countries,37–39 Spain currently lacks any specific regulations or law governing TM. The fact that most healthcare powers are devolved to the Autonomous Communities is a further complication, although this may also represent an opportunity if a robust regional framework is developed that may serve as a scalable model for a subsequent national framework. Fortunately, TM is not lost in no-man’s-land, and is subject to several directly or indirectly related European and Spanish laws (Table 5).

Regulation of telemedicine in Spain and in Europe.36,37

| General Spanish regulations |

| Law 14/1986: General Healthcare Act |

| Law 41/2002 on patient autonomy |

| Law 16/2003 on the cohesion and quality of the national health system |

| Processing of healthcare data |

| Spain: Law 3/2018 of 5 December, on the protection of personal data and guaranteeing digital rights |

| Europe: Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council; Treaty on the functioning of the European Union |

| Electronic communication |

| Spain: Law 34/2002 of 11 June, on information society services and electronic commerce |

| Europe: Electronic Commerce Directive (2000/31/EC) and Directive 98/34/EC on information society services |

| Rights of patients |

| Spain: Royal Decree 81/2014 of 7 February, establishing regulations to guarantee cross-border healthcare |

| Europe: Directive 2011/24/EU on the application of patients’ rights in cross-border healthcare |

Finally, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Central Ethics Committee of the Spanish General Council of Official Medical Colleges9 published the document “La telemedicina en el acto médico. Consulta médica no presencial, e-consulta o consulta online” (Telemedicine in the medical act. Remote consultations, e-consultations, or online consultations), which includes general guidelines based on the principles of medical ethics (the document can be consulted online).

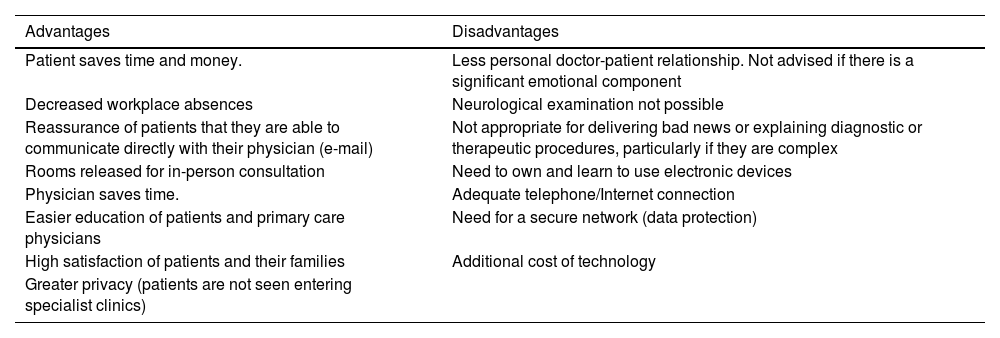

Advantages and disadvantages of telemedicineTM presents numerous advantages for outpatient management (Table 6). Telephone or video consultations can be held from any device physically connected to the network, and therefore do not require a room in a hospital outpatient consultations area. This releases consultation rooms in these areas, which may be used to attend patients who do require in-person consultations, reducing waiting lists. In fact, physicians can even be at home, if they are provided with remote access to the hospital information system.

Summary of the main advantages and disadvantages of telemedicine.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Patient saves time and money. | Less personal doctor-patient relationship. Not advised if there is a significant emotional component |

| Decreased workplace absences | Neurological examination not possible |

| Reassurance of patients that they are able to communicate directly with their physician (e-mail) | Not appropriate for delivering bad news or explaining diagnostic or therapeutic procedures, particularly if they are complex |

| Rooms released for in-person consultation | Need to own and learn to use electronic devices |

| Physician saves time. | Adequate telephone/Internet connection |

| Easier education of patients and primary care physicians | Need for a secure network (data protection) |

| High satisfaction of patients and their families | Additional cost of technology |

| Greater privacy (patients are not seen entering specialist clinics) |

Furthermore, TM care also reduces consultation times. According to a study by the consulting firms PwC and GSMA, European physicians saved 42 million working days in 2017 through the use of TM, reduced healthcare expenditure by nearly 100 billion euros, and were able to treat 126 million new patients.40 TM also offers greater privacy than in-person consultations, as patients are not seen entering the consultations of physicians specialising in specific diseases or in the waiting rooms of particular hospital departments. There is also an environmental benefit, as no physical documents are generated, resulting in considerable savings in paper and ink.

However, TM also presents some disadvantages (Table 6). The doctor-patient relationship may become more impersonal. Therefore, it is not considered an appropriate medium for delivering bad news, for instance after a complementary test. These systems are also inappropriate for explaining complex treatments or diagnostic examinations. In the event of any change in headache symptoms, TM does not allow for the performance of a new neurological examination. Finally, there is a potential risk of confidentiality issues or identity theft.

Clearly, the provision of TM care requires both patient and physician to have suitable devices (computer, mobile phone, webcam, etc) and understanding of their correct and optimal use. It is also essential to have a good telephone and/or Internet connection, as well as access to a secure network guaranteeing the protection of patients’ personal data.41–43

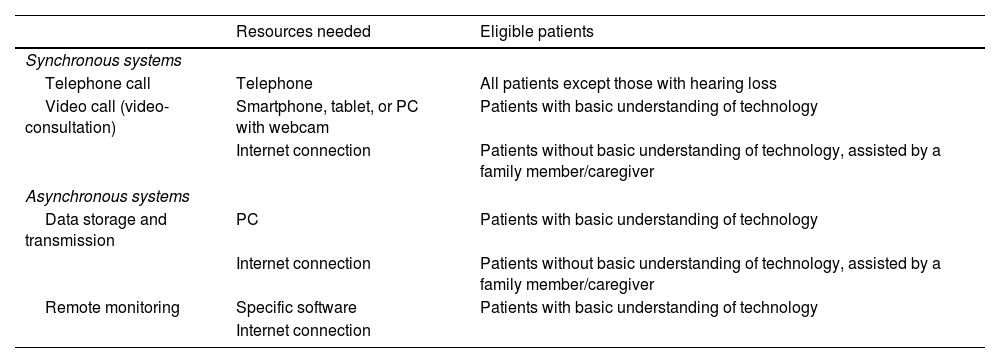

Implementation of telemedicine in headache consultationsTM can be implemented in several ways (Table 7). Broadly speaking, it can be characterised as synchronous (real time) or asynchronous (information is transmitted but is not reviewed in real time).

Types of telemedicine: synchronous and asynchronous.

| Resources needed | Eligible patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Synchronous systems | ||

| Telephone call | Telephone | All patients except those with hearing loss |

| Video call (video-consultation) | Smartphone, tablet, or PC with webcam | Patients with basic understanding of technology |

| Internet connection | Patients without basic understanding of technology, assisted by a family member/caregiver | |

| Asynchronous systems | ||

| Data storage and transmission | PC | Patients with basic understanding of technology |

| Internet connection | Patients without basic understanding of technology, assisted by a family member/caregiver | |

| Remote monitoring | Specific software | Patients with basic understanding of technology |

| Internet connection | ||

- □

Telephone calls. This is currently the most widely used form of remote consultation between physicians and patients.

- □

Real-time video-conferencing (video-consultation). This approach uses live audiovisual transmission to exchange information. It requires an electronic device with audio and video recording, as well as an adequate, stable Internet connection, to establish satisfactory communication between patient and physician. Most of the laptops and smartphones that patients may own are now equipped with integrated cameras enabling this type of connection. Ironically, physicians may have greater difficulty accessing this technology, as desktop computers in their consultations may not have cameras, and they will need to request webcams and third-party software; however, these devices are inexpensive. The advantage of video-consultations over telephone calls is that communication is closer and the meeting can be more similar to an in-person consultation; it may even be possible to conduct a general clinical examination of the patient,44 although craniofacial palpation and eye fundus examination are clearly not possible.

- □

Data storage and transmission (e-mail). E-mail enables the transmission of medical information as text, with or without images, as well as prescriptions, and can be used to address patients’ queries that do not require real-time interactive communication. Both patient and physician must have access to an electronic device capable of accessing and sending e-mail.

- □

Remote monitoring. Remote or at-home monitoring is the use of technology to transmit data from a device implanted in a patient to the specialist’s consultation.41 In the field of headache, the most similar applications are e-health (electronic health) platforms, which include various functions designed to improve communication between patients and physicians, to empower patients in the management and treatment of their disease, to detect symptoms early, and to individualise care interventions through the use of data recorded on the platform by patients.45

As the implementation of TM resources constitutes a change in care provision, the first step to be taken is the design and approval of a plan by the centre’s clinical directors. Prior to this, it is advisable to establish what TM resources are available in the Autonomous Community; these should be used over a secure network and/or platform to guarantee compliance with Spanish data protection legislation. Therefore, evaluation by the centre’s legal and IT departments is important in ensuring compliance.46,47

To be considered eligible, patients must know how to use common devices (smartphones or computers), without necessarily being e-patients (patients, typically “digital natives,” who are highly connected to technology and naturally use it to care for aspects of their health). These skills are sufficient to maintain correspondence by e-mail and video-consultations.

As the majority of patients attended at headache consultations are young and well familiarised with these technologies, the ideal outcome would be to implement video-consultations as the norm. However, we also attend older patients (those with neuralgias, hypnic headache, cervicogenic headache, etc), who are typically less familiar with these types of resources. In the absence of a family member or caregiver who can offer support, the simplest solution is to hold telephone consultations. Each case should be assessed on an individual basis, especially in patients older than 60-65 years.

Finally, clinical records should include a note on the form of consultation, after the patient is informed and consents to the new format. The date and time of the next consultation should also be scheduled, with the duration established according to the objectives of the consultation, rather than the tool used.

Conclusions and recommendationsBased on our analysis of the current situation of TM in the management of patients with headache or neuralgia in Spain, we may draw the following conclusions:

- □

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the mean waiting time for in-person care at headache units/clinics.

- □

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a growth in the use of TM, although its implementation and continued use require increased levels of human and technological resources.

- □

Telephone and e-mail are currently the most widely used TM tools, although neurologists are aware of the need to broaden the forms of TM on offer, including such other tools as video-consultations, e-health, and m-health.

- □

Generally, patients with headache and neuralgias are ideal candidates to benefit from TM. Due to their age, which is below the mean for our specialty, they are more capable users of ICT.

GECSEN advises and encourages all neurologists attending patients with headache and neuralgias to consider the implementation of TM resources, ideally focusing on video-consultation. However, in the absence of a legal framework regulating TM in Spain, it is essential for these efforts to be advised and approved by legal and IT departments and hospital management prior to implementation of TM.

After the initial appointment, which must always be in person, any stable patient with headache and/or neuralgia may be eligible for periodic follow-up by TM. This form of care is not appropriate for patients undergoing semi-invasive procedures (onabotulinum toxin A infiltration and/or anaesthetic blocks) or receiving parenteral administration of monoclonal antibodies (first consultation), or for carriers of neuromodulation devices. It is also inappropriate for following up patients with refractory headache and/or neuralgia, for explaining complex procedures (eg, surgery), or for delivering bad news or prognosis (concerning findings from a complementary examination, for instance). GECSEN recommends the use of video-consultation for patients younger than 60-65 years, and telephone consultations for older patients, although each case should be considered on an individual basis; it should be noted that there is a growing number of older people with sufficient digital proficiency.

TM emerged in clinical practice as the result of a viral pandemic. Its current impetus will largely decrease in line with the resolution of the COVID-19 pandemic, in other fields of neurology and other specialties; however, in the area of headache and neuralgias, all evidence suggests that TM is here to stay. We must accept and normalise this change as soon as possible. This development also represents a fertile new field of clinical research.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.