Brochures are commonly used as educational tools in daily neurological practice. They are provided to increase the general population's knowledge of a specific disease and also to combat sources of erroneous information. Surveys are the most commonly used method of ascertaining user satisfaction with services received.

ObjectivesThis study will assess patient-perceived satisfaction and provide feedback to measure the comprehensibility and overall utility of an educational brochure on migraine.

Material and methodsOpen prospective multicentre study of a group of patients diagnosed with migraine in neurology clinics in Alicante province. During the initial visit, each patient received a migraine brochure prepared by the Valencian Society of Neurology's study group for headaches (CEFALIC). During a follow-up visit, they were then asked to fill out a personal survey on the overall quality of the information in the brochure.

ResultsWe included a total of 257 patients diagnosed with migraine (83% episodic migraine; 17% chronic migraine); mean age was 37.6 years. Two hundred seven patients confirmed having read the brochure (80.5%); 50 patients (19.5%) either forgot to read it or had no interest in doing so. The brochure seemed interesting and easy to understand according to 90% of the patients. Seventy-six per cent of the respondents stated that reading the brochure increased their overall knowledge of migraine, while 50% of the patients found the brochure useful for improving migraine control.

ConclusionsPatients found the migraine educational brochure to be comprehensible, a means of increasing overall knowledge of the disease, and useful for increasing control over migraines. Evaluations of the educational brochures that we provide to our patients with migraine should be studied to discover the causes of dissatisfaction, determine the level of quality of service, and investigate potential areas for improvement.

Los folletos informativos son una herramienta educativa habitual en la práctica neurológica diaria; mediante este mecanismo se pretende incrementar de primera mano los conocimientos que la población tiene sobre una enfermedad concreta, además de evitar fuentes de información erróneas. Las encuestas son el medio más empleado para conocer la satisfacción de los usuarios con los servicios recibidos.

ObjetivosEvaluar la satisfacción percibida y establecer una retroalimentación informativa que valore la comprensión y la utilidad global de un folleto educativo sobre migraña.

Material y métodosEstudio abierto, prospectivo y multicéntrico sobre una población de pacientes diagnosticados de migraña en diversas consultas de neurología de la provincia de Alicante. En la visita basal se les entrega un folleto informativo de migraña confeccionado por el grupo de estudio para la cefalea de la Sociedad Valenciana de Neurología (CEFALIC). En la visita control se les solicita la cumplimentación de una encuesta personal y por escrito sobre la calidad global de la información incluida en el folleto.

ResultadosSe incluye a un total de 257 pacientes diagnosticados de migraña (83% migraña episódica; 17% migraña crónica), con una edad media de 37,6 años. Confirmaron la lectura del folleto 207 paciente (80,5%) y no lo habían leído 50 pacientes (19,5%), bien por olvido bien por desinterés. Al 90% de los pacientes la lectura del folleto les pareció interesante y comprensible. El 76% de los encuestados opina que la lectura del folleto incrementa sus conocimientos sobre migraña. El 50% de los pacientes opina que el folleto resultó de utilidad para mejorar el control de su migraña.

ConclusionesLa utilización de un folleto educativo sobre migraña resultó comprensible, además incrementó el conocimiento global de la enfermedad y en opinión de los pacientes resultó útil para mejorar el control de su migraña. La evaluación de la información educativa que prestamos a nuestros pacientes con migraña debe ser medida para descubrir las causas de descontento, determinar el nivel de calidad del servicio e investigar las posibilidades de mejora de calidad.

Many associations of doctors, regulatory agencies, educators, researchers, and patients are aware that effective communication is essential for good medical care. Acknowledging and reinforcing the role of patients in different stages of the care process guarantees quality healthcare.1 As a result, current guidelines for managing chronic illnesses, including guidelines for migraine management,2 underscore the necessity of improving communication channels by means of educational programmes aimed at fostering self-management. Several authors have highlighted how important it is for patients to be able to control the wide variety of factors involved in quality of life.3

Educational programmes have traditionally focused on providing patients with information and teaching technical skills that were often difficult to understand and put into practise. The concept of self-management represents a paradigm shift in the doctor-patient relationship. Self-management education gives patients the tools and the independence necessary to solve problems arising during the course of chronic diseases.4 The end goal would be to promote shared decision-making by providing patients with comprehensible summaries of scientific evidence and encourage patients and doctors to work together in selecting treatments or healthcare strategies.

The quality of medical information, and the ability to transmit it using the many tools available at present, is correlated with greater patient satisfaction and treatment compliance, a lower risk of medical errors, reduced healthcare costs, and greater satisfaction for healthcare providers.1 Implementing migraine education programmes has been proved to have a substantial impact on patients’ knowledge of the disease, which results in greater patient satisfaction with the care received.5 Self-management brochures help patients choose the most suitable treatment option for each situation and therefore contribute to improving quality of life. They also provide an alternative to the numerous sources of erroneous information that are unfortunately proliferating with the help of new technologies. Patients with migraine are interested not only in accessing objective, accurate information on how to improve control over their disease, but also in having a more interactive relationship with the doctors treating them.6

The National Headache Foundation, the American Council for Headache Education, and the American Headache Society produce informative brochures on migraine that can be found in waiting rooms, which has proved to be a very useful and inexpensive educational strategy.5,6 However, these brochures must be presented and structured in such a way that the information is transmitted as clearly as possible.7 Despite the potential usefulness of brochures as a means of transmitting information, patients with migraines still prefer face-to-face communication and telephone consultations with the doctor to such other channels as brochures or websites, which are regarded as secondary information sources.8

In order to evaluate the usefulness of brochures, the headache study group (CEFALIC) of the Valencian Society of Neurology designed a brochure on migraine offering predominantly practical information about predisposing and triggering factors for migraine crises or progression to chronic migraine, as well as easy-to-understand information about the treatments available. At the same time, we know that interviews are the most widely used tool for measuring care quality and patient satisfaction with a service since they offer information about their needs and preferences from a unique viewpoint.9 For purposes of gathering patient feedback that could later be studied by researchers in the CEFALIC group, a survey was designed to evaluate how many patients had actually read the educational brochure handed out to patients at the clinic, the degree of understanding and satisfaction they displayed, whether the brochure provided new information on migraine, and the patients’ impressions about the usefulness or effectiveness of the information provided to improve migraine management.

Material and methodsWe conducted a multicentre prospective longitudinal and observational study including consecutive patients diagnosed with migraine in 10 neurology departments in Alicante province. The inclusion criterion was being diagnosed with migraine (with or without aura, or chronic) according to the diagnostic criteria given in the second edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-2).10 Both sexes and all ages were accepted. We collected the following data: age, sex, type of migraine (episodic migraine with or without aura, chronic migraine), level of education (little or no schooling, primary education, secondary education, university education), and current occupational status (unemployed, homemaker, employed, retired, student).

Patients were given the information brochure created by the CEFALIC group during the initial consultation. The contents of the brochure were drawn up by a working group of neurologists based on the diagnostic criteria of the ICHD-210; a literature review was subsequently conducted to evaluate aspects directly related to management of patients with migraine based on the recommendations listed in the Spanish Society of Neurology's official guidelines for diagnosing and treating headache (2011).11 However, it was not our purpose to compare contents of our brochure to the contents of brochures provided by other entities. A consensus meeting was subsequently held to conclude that, based on experts’ clinical experience, the brochure covered the most relevant aspects that patients should know about their disease. The brochure included the following sections: (1) definition of migraine; (2) knowledge as the key to managing migraine correctly; (3) analgesic treatment; (4) preventive treatment; (5) non-pharmacological treatment; and (6) basic rules for effective migraine control. The brochure is available from the Valencian Society of Neurology's website (http://www.svneurologia.org/qs/CEFALIC/FOLLETO%20DE%20MIGRAAS.pdf). During their next visit, patients were requested to complete a survey about the quality of the brochure. Participation in this stage was voluntary and anonymous.

The survey included 6 main items: brochure readability, clarity of the information provided, quality of the information provided, contribution to the patient's knowledge of migraine, usefulness for migraine management, and global quality of the brochure (Appendix 1). Each item was assessed using a Likert-type scale12,13 with 5 possible response options: 1=completely disagree; 2=disagree; 3=neither agree nor disagree; 4=agree; 5=completely agree. The 5 possible response options provided for the item evaluating global quality of the brochure were very good, good, average, poor, and very poor. In order to develop the satisfaction survey, we included a selection of those items evaluating the concepts of interpretability, item length, validity, discriminant ability, and homogeneity. The neurologists participating in the study concluded, in a subsequent consensus meeting, that the survey reflected the main aspects needed to assess patient satisfaction with the brochure.

Data were entered in an Excel spreadsheet; the statistical analysis was conducted using descriptive statistics (mean±SD) for quantitative variables and frequency distributions for qualitative measurements. We compared the characteristics of patients who had read the brochure with those of the patients who had not read it using the Chi-square test and the Fisher exact test, with a significance level of P=.05. The statistical analysis of all variables was performed using G-Stat statistical software version 2.0.

ResultsSociodemographic and clinical description of patientsWe interviewed a total of 257 patients who had received the brochure (209 women and 48 men). Mean age was 36.58±11.96 years. Patients with episodic migraine accounted for 82.27% of the total, while 17.7% of patients had chronic migraine.

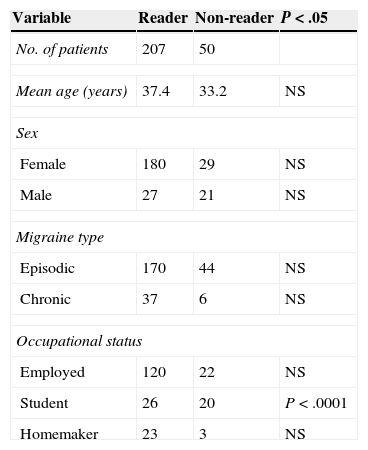

Reading and understanding the brochureA total of 207 patients (80.54%) stated that they had read the brochure (reader group), while 50 patients (19.4%) stated they had not read it (non-reader group). Table 1 shows the demographic variables analysed for each of the 2 groups. There were statistically significant sex differences in the percentages of non-readers: 43.75% for men and 13.88% for women. However, the percentage of readers was lower among patients with episodic migraine (79.4%) than in the chronic migraine group (86%). Regarding occupational status, the percentage of readers was significantly lower among students (56.5%) than in the actively employed (84.5%) and/or homemakers (88.5%) (P<.0001).

Distribution of variables for readers and non-readers.

| Variable | Reader | Non-reader | P<.05 |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 207 | 50 | |

| Mean age (years) | 37.4 | 33.2 | NS |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 180 | 29 | NS |

| Male | 27 | 21 | NS |

| Migraine type | |||

| Episodic | 170 | 44 | NS |

| Chronic | 37 | 6 | NS |

| Occupational status | |||

| Employed | 120 | 22 | NS |

| Student | 26 | 20 | P<.0001 |

| Homemaker | 23 | 3 | NS |

The most frequently reported causes for not reading the brochure were forgetfulness (60%), lack of interest (22%), and lack of time (10%). Patients in general considered the brochure to be interesting (68%), and 92% agreed or completely agreed that the information was clearly presented and that the brochure was easy to read and understand; only 1% found the information unclear.

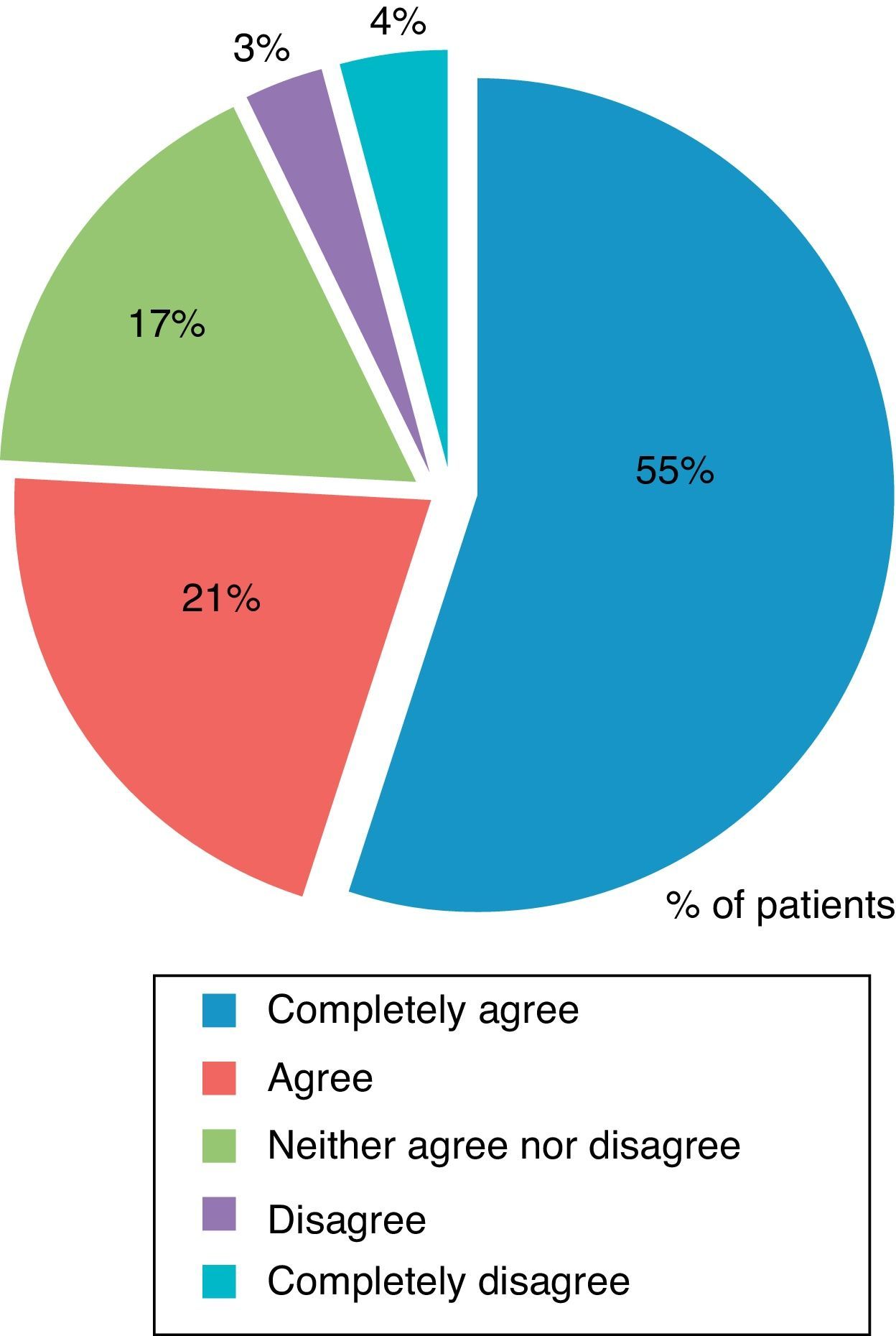

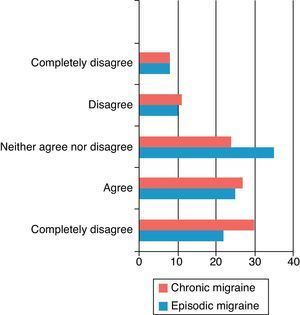

Global quality of the brochure informationSeventy-six percent of patients agreed that the brochure had increased their knowledge about migraine, while 3% disagreed and 4% completely disagreed with that statement. There were no significant differences regarding increased knowledge about migraine between groups broken down by migraine type (Fig. 1).

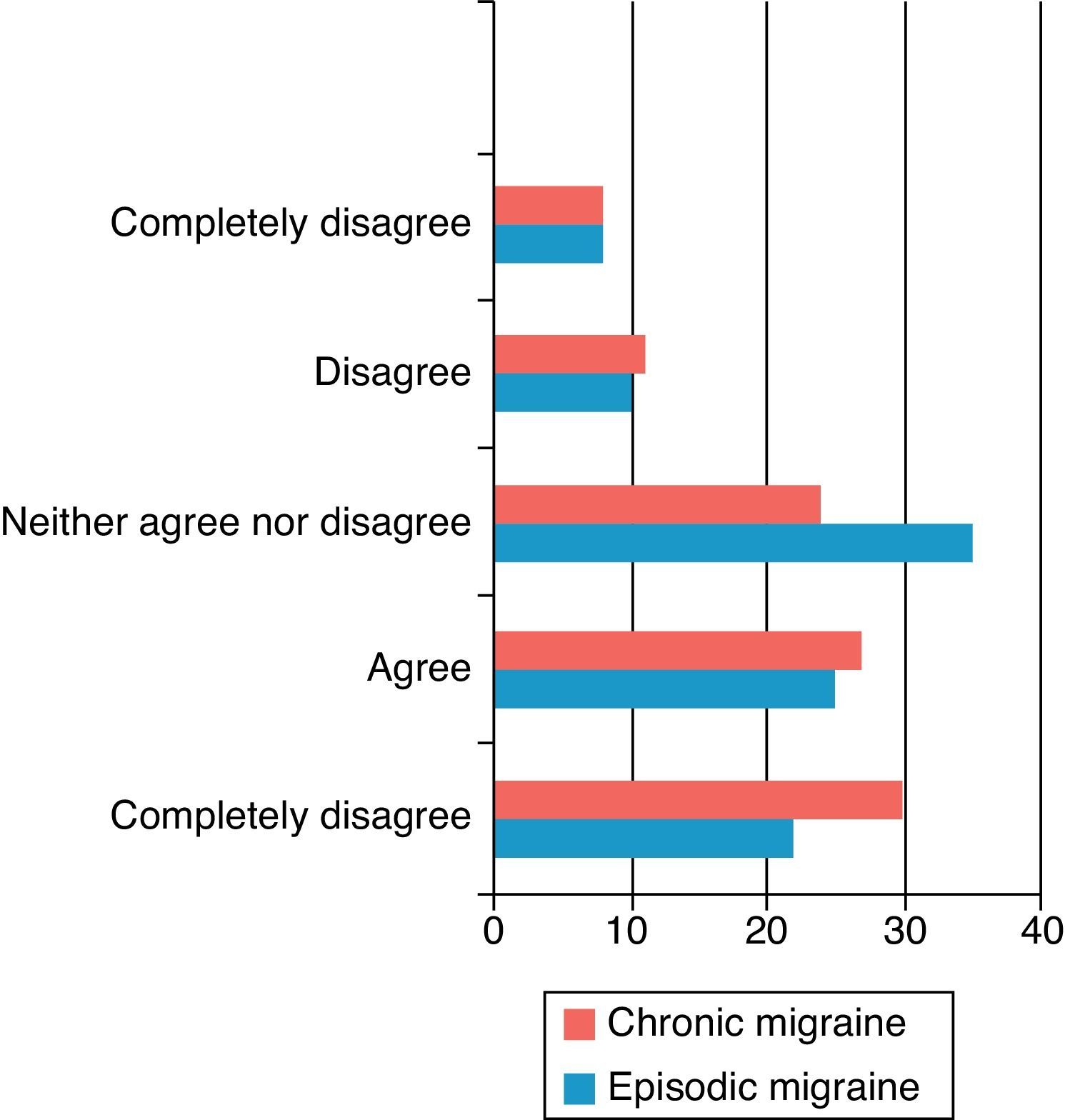

In answer to whether the brochure was useful for improving migraine management, a large percentage of patients (33%) neither agreed nor disagreed, 50% regarded it as a useful tool, and only 17% disagreed; no significant differences were found between groups broken down by migraine type (Fig. 2).

Overall quality of the brochure was rated as good or very good by 96% of patients, while 4% of them rated it as average, and no patients considered it to be poor or very poor. While 97% of patients would recommend the brochure to other patients with migraine, 70% stated that it should contain additional information. On item number 8 of the survey, patients were asked if it was necessary to include some additional recommendations according to what each patient felt to be pertinent. The item included a comment box where patients could write their suggestions. Seventy percent of the patients who had read the brochure stated that it was not necessary to include additional information, 14% felt that more information was necessary (suggestions in the comment box were varied and non-specific, with prevention and alternative treatments being the most common requests), and 16% did not answer or checked the box for ‘no response/do not know’.

DiscussionAt present, there are no articles in the literature addressing achieving patient satisfaction with the aid of informative brochures. Our study therefore explores a new area in clinical practice and provides useful information about the importance patients assign to the information they read in migraine education brochures. Our results confirm that patients diagnosed with migraine willingly accept written information in the form of informative brochures about their disease (80% of the patients read the brochure). Among the most commonly adduced causes for not reading the brochure were forgetfulness and lack of interest in doing so. Nearly half of all male patients did not read the brochure. It may come as a surprise that such a large percentage of students did not read the brochure. However, a study conducted in Singapore showed that Internet and short messages were the most widely accepted means of access to medical information among young people and those with higher education levels.14

The main purpose of the present study was to analyse the level of overall satisfaction with the quality of the contents of the brochure. Broadly speaking, satisfaction rates were high, especially regarding clarity and global quality. We found no significant differences in patients’ perception of quality and clarity of the information between episodic and chronic migraine patients. However, we were unable to confirm this finding since no studies in the literature address this point. Likewise, the group with the most severe form of migraine (patients with chronic migraine) may be expected to already have abundant information about the disease, which might lead them to give the brochure a poorer evaluation. However, our results do not support this hypothesis. This may be due to the fact that patients with migraine, regardless of the level of severity, usually dispose of little information, and therefore welcome any type of reading material on the disease.

The COMOESTAS consortium project,8 published in 2011 by Munksgaard et al., included a pilot study in 3 European countries to analyse the expectations of treatment outcomes and preferences for information sources in a group diagnosed with chronic migraine. The researchers found that the information channels preferred by most patients were face-to-face personal verbal information and telephone consultations. Only a third of the patients preferred alternative channels of information (brochures, websites). Brochures were not a popular option since they usually provide very general information and lack more specific content that patients might find helpful.8 In our study, the high percentage of patients who regarded the brochure as clear and easy to understand leads us to conclude that the brochure design was successful for communicating high-quality information at a level that the general population finds accessible. The informative brochure was therefore a useful tool for increasing patients’ knowledge of migraine management since it provides comprehensive information about the disease. Studies analysing the importance of education for migraine patients and its impact on outcomes are scarce. In a study of 284 patients with migraine, published by Smith et al.5 in 2010, simple educational materials were shown to improve general knowledge about the disease, which led to increased satisfaction with the care patients received. Likewise, increased satisfaction resulted in fewer migraine crises, reduced migraine intensity, and improved quality of life overall. In 2006, Rothrock et al.15 conducted a comparative study in 2 groups of university students with migraine who were randomised to attend or not attend a workshop about migraine management. The researchers observed that the group attending the workshop experienced fewer migraine episodes per month and fewer incapacitating headache days per month, decreased use of analgesics and rescue treatments, and greater compliance with preventive treatment. Furthermore, these patients made fewer unscheduled visits to the clinic due to migraine. These findings are in line with those reported by studies in patients with other chronic illnesses (diabetes mellitus, asthma, cardiovascular diseases, among others), in which providing basic education about the disease resulted in lower morbidity and lower levels of concern and anxiety.

As stated in a study by Allen et al.,16 new technologies have opened the door to new ways of transmitting information, enabling closer interaction between patients, information providers, and caregivers. Although these technologies offer an efficient, low-cost, innovative approach to chronic illness management, the impact of the information that reaches the patient depends on patients’ previous knowledge and the level of individual support from the educator. For example, the study by Cady et al.17 evidences the changes in satisfaction experienced by both patients and professionals providing information about migraine in CD-ROM/DVD format. The study included 4 groups: group A watched the CD-ROM/DVD with a nurse trained to answer their questions, group B watched the material with a nurse familiar with the CD-ROM/DVD, group C watched the CD-ROM/DVD with a nurse who had not seen the material, and group D received no information. The patients who best assimilated the information were those in group A since they not only received information, but also were supported by a qualified healthcare professional who answered their questions. Websites providing access to large volumes of specialised information should not be too general or misleading, and they must be periodically reviewed by a medical authority to endorse that content and adapt it to a lay audience while guaranteeing quality.8,18

Our study shows the need to develop new communication channels to provide user-friendly high-quality information. Educational material on health-related topics is only effective when it can be read, understood, and remembered by patients.19 Our survey has shown that patients rated our educational brochures positively based on the increase in their overall knowledge of the disease and tips oriented towards self-management, which in turn improves treatment compliance and quality of life. A number of controlled studies including patients with diverse illnesses have shown that providing self-management instructions (1) is more effective than simply repeating information, and (2) may reduce costs in some cases since they can decrease use of healthcare resources. Transmitting information is useful when both the educator and the patient are fully committed: patients are interested in understanding what occurs in migraine, in addition to knowing how to relieve pain. In fact, patients wish to build cooperative relationships with their doctors, and they prefer a team-based approach to treatment.6

Our study has several limitations. First, there was the loss of information about patients receiving a brochure who did not attend the follow-up appointment. Second, waiting times for the follow-up consultation were too long and may have contributed to patients’ forgetting to read the brochure. Furthermore, the interviewer may have influenced survey responses. Likewise, our study displays the limitations inherent to Likert-type scales. Despite the study limitations described above, we feel that our results accurately reflect the current situation in patient care: patients need information about their disease and user-friendly self-management instructions have a positive impact on patients’ health.

In conclusion, the CEFALIC group feels that handing out easy-to-understand educational brochures about migraine in neurology clinics is a low-cost, effective means of increasing patients’ knowledge about the disease that also contributes to improving migraine self-management. Lastly, the evaluations of the educational material provided to our migraine patients should be analysed to determine the reasons for low satisfaction, measure the perceived quality of our educational services, and investigate opportunities for increasing quality.

FundingThe authors of the present study have received no funding for developing the brochure, the survey, or this study. The costs of printing the information brochure were financed by Almirall, S.A.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Medrano Martínez V, Callejo-Domínguez JM, Beltrán-lasco I, Pérez-Carmona N, Abellán-Miralles I, González-Caballero G, et al. Folletos de información educativa en migraña: satisfacción percibida en un grupo de pacientes. Neurología. 2015;30:472–478.