Hyponatraemia, the most prevalent electrolyte imbalance in clinical practice, is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. The association between hyponatraemia and Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) has been described in the literature, although few studies have analysed its prevalence, aetiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. We present the case of a patient with GBS and severe hyponatraemia.

The patient was a 59-year-old man with type 2 diabetes mellitus and good metabolic control. He attended our hospital due to paraesthesia in the hands and feet and difficulty walking (2 falls at home), loss of sphincter control (requiring a urinary catheter), general discomfort, and drowsiness. Three weeks previously, the patient had presented diarrhoea, which lasted 3 days and resolved spontaneously. The examination revealed symmetric paraparesis, hypoaesthesia in both hands, and generalised areflexia. The patient was adequately hydrated and did not present oedema. A blood analysis revealed a low sodium concentration at 121mEq/L (normal range, 135-145mEq/L) and a glucose level of 168mg/dL (normal range, 80-120mg/dL), with normal potassium, urea, creatinine, and total protein concentrations; a head CT scan revealed no abnormalities. A CSF analysis detected albuminocytologic dissociation, a protein level of 2.34g/L (normal range, 0.15-0.5g/L), and a cell count of 8cells/mm3. The microbiological analysis yielded negative results. Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (a form of GBS) and euvolaemic hyponatraemia.

We started treatment with immunoglobulins (Ig) dosed at 0.4g/kg/day, in 5 boluses. However, treatment only achieved partial motor improvements, and an additional cycle was necessary 2 weeks later. Electroneurography and electromyography studies performed during hospitalisation confirmed the diagnosis. Neurological symptoms improved progressively; at discharge (a month after admission), however, the patient continued to display lower limb weakness, which prevented him from walking.

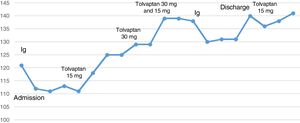

Physical examination results were compatible with euvolaemic hyponatraemia. Plasma osmolality was 239mOsm/kg (normal range, 275-295mOsm/kg), urine osmolality was 591mOsm/kg (normal range, 100-700mOsm/kg), urine sodium concentration was 80 mEq/L (normal range, 20-200 mEq/L), and TSH concentration was 1.70mIU/mL (normal range, 0.4-4mIU/mL); the patient showed a normal lipid profile and no monoclonal proteins in protein electrophoresis. Chest radiography revealed mediastinal widening; a chest and abdomen CT scan revealed no signs of tumour. The patient was diagnosed with euvolaemic hyponatraemia associated with syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) secondary to GBS. The patient was initially treated with 3% hypertonic saline (500cc/24h) and water restriction (800cc/24h); we subsequently administered tolvaptan dosed at 15mg/day due to lack of response. The drug was up-titrated to 30mg/day, and progressively withdrawn on an outpatient basis until complete discontinuation 4 months later.

One year later, lower limb weakness had improved with rehabilitation therapy, although the patient needed crutches to walk. Serum sodium levels were normal (141mEq/L).

Although some studies report an association between hyponatraemia and GBS, few studies have analysed the correlation. This association results in poorer hospital outcomes even at one year,1–5 longer hospital stays,1–3 and higher costs.1 The association between hyponatraemia and GBS is even reported to be an independent predictor of mortality,2,5 which has also been described in other disorders.1 Some studies suggest that patients with GBS and hyponatraemia are more likely to require ventilatory support,1,2 which may be explained by the fact that severe hyponatraemia can manifest as respiratory distress.6

Most cases of hyponatraemia in the context of GBS develop during hospitalisation and are associated with Ig treatment; pseudohyponatraemia linked to increased protein levels may therefore play an important role. Another possibility is associated with water transport from the intracellular space to the intravascular space due to increased osmolality secondary to infusion of sugar-stabilised Ig. Palevsky et al.7 analysed the effect of Ig infusion on sodium levels, measured with direct potentiometry to avoid diagnosis of pseudohyponatraemia. The authors observed hyponatraemia, despite using this technique. SIADH is a frequent cause of true hyponatraemia in patients with GBS.2,8,9 Other cases are due to cerebral salt-wasting syndrome, although this association is very rare.

Our patient may meet the diagnostic criteria for SIADH as established in the latest European hyponatraemia guidelines (plasma osmolality<275mOsm/kg; urine osmolality>100mOsm/kg; euvolaemia; and absence of adrenal insufficiency, hypothyroidism, hypopituitarism, or kidney failure).7 We did not determine cortisol levels in our patient; however, clinical and laboratory results were not compatible with adrenal insufficiency. The prevalence of SIADH in patients with GBS is not clear; case reports constitute the only available evidence. The pathophysiological mechanisms of the association between GBS and hyponatraemia are yet to be understood. Several hypotheses have been proposed: alterations of hypothalamic cells, causing ADH release into the bloodstream; alterations in osmoregulation; increased sensitivity of ADH receptors; and other mechanisms not related to ADH.9 Other researchers support the involvement of interleukin 6, which may increase vasopressin release.10

Interestingly, our patient's sodium levels decreased following Ig administration (Fig. 1). This may indicate pseudohyponatraemia and/or water transport to the intravascular space, which play a role in true hyponatraemia. In retrospect, this may explain the patient's poor response to hypertonic saline and water restriction and the need to up-titrate tolvaptan to 30mg/day to achieve normal sodium levels.

The available evidence on treatment with tolvaptan in patients with GBS and SIADH is strikingly scarce: to our knowledge, only one case has been published to date.

Sodium levels should be monitored in patients with GBS. Pseudohyponatraemia, water transport, and SIADH should be considered in the differential diagnosis of hyponatraemia. In our case, hyponatraemia may have played a role in the need for an additional cycle of Ig and the slow motor recovery.

Please cite this article as: Ternero Vega JE, León RG, Delgado DA, Baturone MO. Síndrome de Guillain-Barré e hiponatremia. Neurología. 2020;35:282–284.