Brugada syndrome is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder caused by a mutation in the genes SCN5A (in 20% of the cases) and SCN1A (in 17% of the cases). SCN5A codes for the alpha subunit of the voltage-gated sodium channel.1 These mutations affect phases 0 and 1 of the depolarisation potential.2 Since this syndrome is a channelopathy, it has been associated with epileptic seizures in some cases. We present 2 patients with Brugada syndrome and epilepsy and review the available literature on this unusual association.

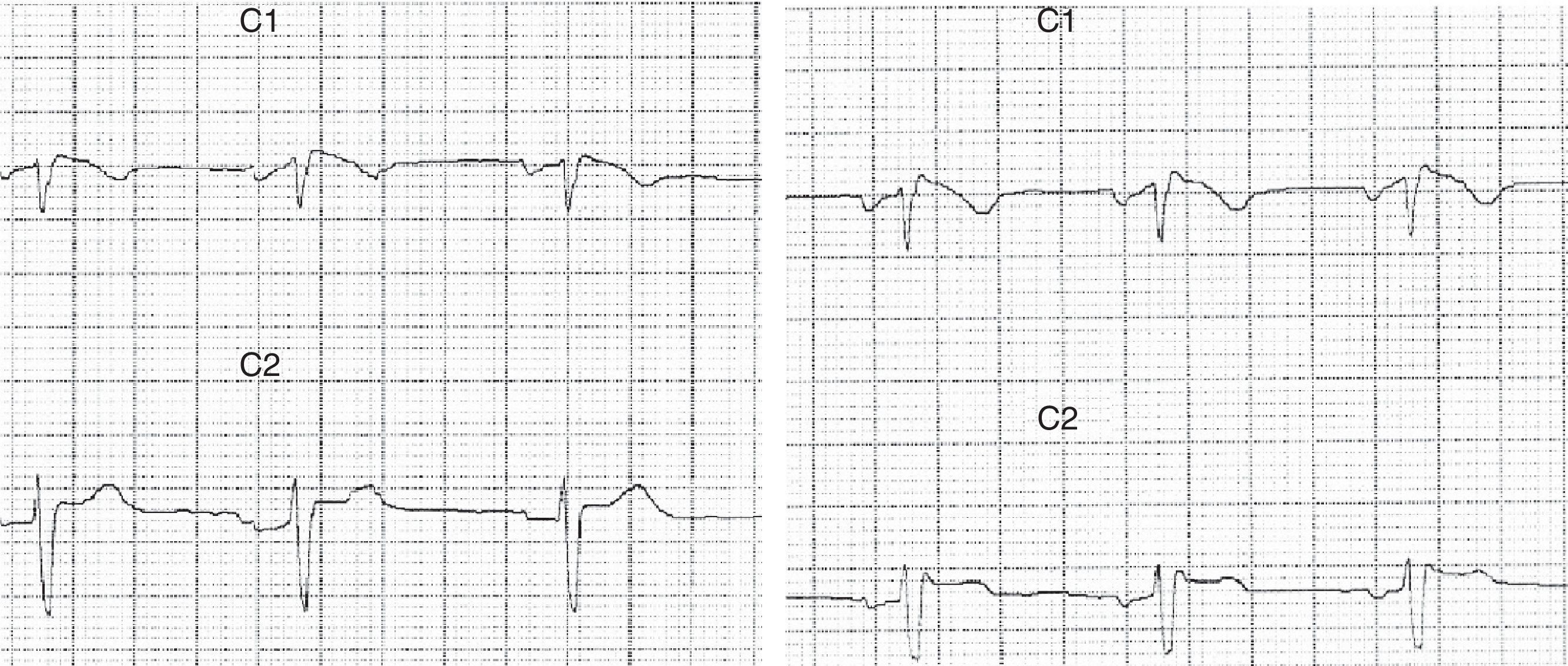

Patient 1Our first patient was a 37-year-old man with a history of repeated episodes of syncope; his father had a pacemaker implanted due to cardiac arrhythmia of unknown causes. The patient visited the emergency department due to a series of self-limiting tonic-clonic seizures followed by confusional state. Blood tests yielded normal results. Brain CT and MRI scans displayed no alterations. The eletrocardiography (ECG) revealed an RSR’ pattern in lead V1 with T-wave inversion and ST segment elevation in lead V2 (Fig. 1). Holter ECG showed sinus rhythm with frequent atrial extrasystoles. Ajmaline test results were compatible with Brugada syndrome. The echocardiogram revealed no abnormalities. Our patient was treated with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Seizures were controlled with valproic acid dosed at 1500mg/day. Our patient remains seizure-free to date.

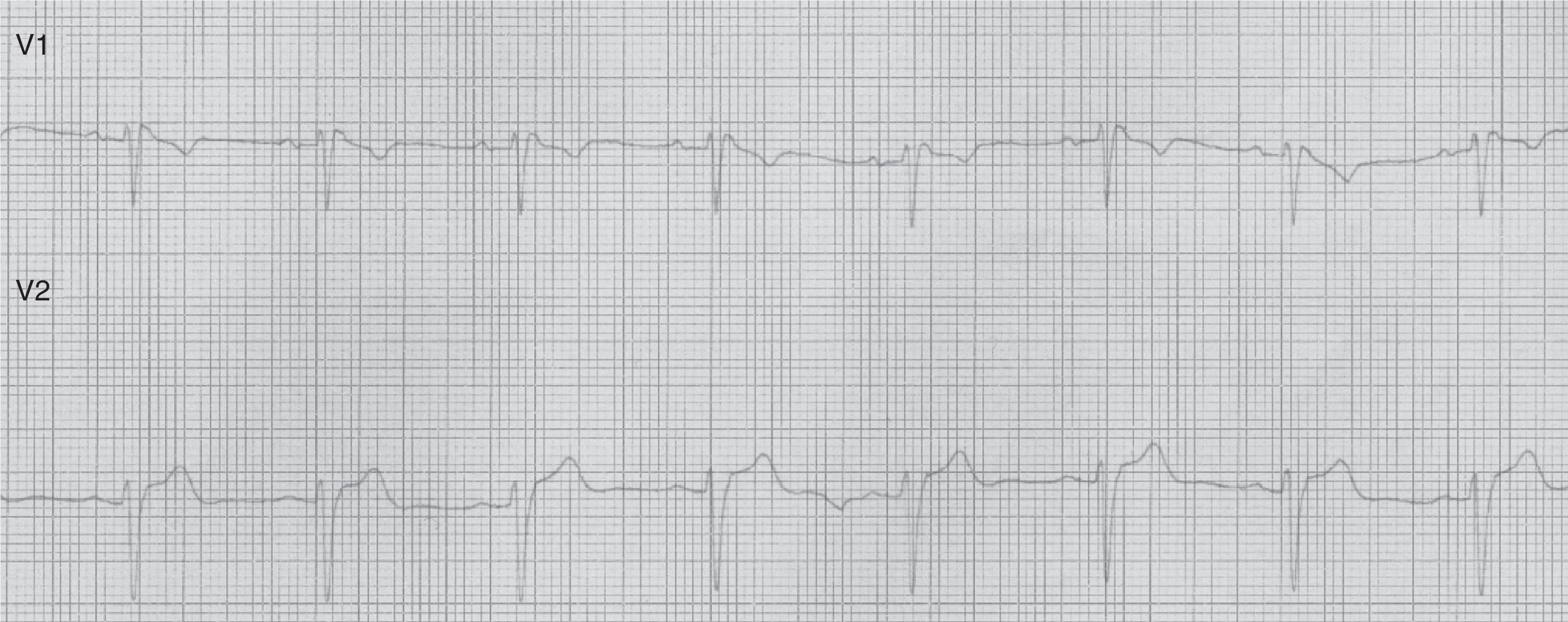

Patient 2Our second patient was a 49-year-old man with a history of arterial hypertension. His father had died suddenly at the age of 57 and a first-degree relative had experienced febrile seizures. While asleep, he experienced 2 self-limiting tonic-clonic seizures lasting a few minutes each, followed by confusion. Our patient was admitted to our hospital. The physical examination yielded normal results. The ECG revealed sinus tachycardia, a QRS complex with an RSR’ pattern in lead V1, and coved ST segment elevation in lead V2: these patterns were compatible with Brugada syndrome (type 3 ECG pattern) (Fig. 2).

Brain MRI, blood test, Holter ECG, and echocardiography results were normal. The electroencephalography (EEG) revealed right fronto-temporal spikes that were more pronounced during sleep stages 3 and 4. Our patient tested positive on the flecainide test. Levetiracetam dosed at 2000mg/day rendered the patient seizure-free.

Brugada syndrome is characterised by ECG alterations, indicating a predisposition to tachyarrhythmias and sudden death. Sudden death typically occurs around the age of 40, at night and while the patient is resting; fever and increased vagal tone have been suggested as potential trigger factors.3 Brugada type 1 ECG pattern is characterised by incomplete right bundle branch block (RSR’), ST segment elevation >2mm in leads V1-V3, and T-wave inversion; ST segment elevations have also been described in inferior leads.4 The coved pattern (RSR’ with the descending arm of the R’ wave coinciding with the beginning of the ST segment) corresponds to Brugada types 2 and 3. However, these ECG changes are transient, random, and may not always appear in a routine ECG. Therefore, such sodium channel blockers as procainamide, ajmaline, and flecainide may be used to trigger these ECG patterns and diagnose the underlying syndrome. The SCN5A gene has been found to play a role in long QT syndrome (LQTS) by either reducing or increasing function of the sodium channel subunit5 (function decreases in Brugada syndrome).

Heritable channelopathies are associated with paroxysmal dysfunction of excitable tissues (heart, brain, muscles). According to experimental models in mice, the SCN5A protein is expressed in the limbic lobe and may play a relevant role in neuronal activation.6 The SCN5A gene is particularly active in astrocytes, which means that any alterations in that gene may confer susceptibility to recurrent seizure activity.7 In our second patient, symptoms and findings may point to nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy, which has an autosomal dominant component linked to ion channel alterations. According to the literature, Brugada syndrome should be considered in healthy patients with nocturnal seizures and urinary incontinence.8

Molecular defects affecting sodium channels may be temperature-dependent; the literature reports one case with fever and 2 with conduction disorders.9,10

Potassium channelopathies constitute another type of channelopathy associated with epilepsy and heart disorders11: KCNH2 channel dysfunction causes type 2 LQTS and KCNQ1 channel dysfunction leads to type 1 LQTS.

Recognising conduction disorders in epileptic patients poses a true clinical challenge; the same is true for seizures in patients with conduction disorders. Symptom exacerbation and ECG changes after treatment with antiepileptics that act by blocking sodium channels are clues that may contribute to the diagnosis of sodium channelopathies.

FundingThe authors have received no private or public funding for this case report.

Please cite this article as: Camacho Velásquez JL, Rivero Sanz E, Velazquez Benito A, Mauri Llerda JA. Epilepsia y síndrome de Brugada. Neurología. 2017;32:58–60.

This study has not appeared previously in print, nor has it been presented in any meetings or congresses.