In Spain, stroke is the leading cause of death in women as well as the leading cause of disability in adults. This translates into a huge human and economic cost. In recent years there have been significant advances both in the treatment of acute stroke and in the neurorehabilitation process; however, it is still unclear when the best time is to initiate neurorehabilitation and what the consequences of delaying treatment are. To test the effect of a single day delay in the onset of neurorehabilitation on functional improvement achieved, and the influence of that delay in the rate of institutionalisation at discharge.

MethodsA retrospective study of patients admitted to Parkwood Hospital's Stroke Neurorehabilitation Unit (UNRHI) (University of Western Ontario, Canada) between April 2005 and September 2008 was performed. We recorded age, Functional Independence Measurement (FIM) score at admission and discharge, the number of days between the onset of stroke and admission to the Neurorehabilitation Unit and discharge destination.

ResultsAfter adjustment for age and admission FIM, we found a significant association between patient functional improvement (FIM gain) and delay in starting rehabilitation. We also observed a significant correlation between delay in initiating therapy and the level of institutionalisation at discharge.

ConclusionsA single day delay in starting neurorehabilitation affects the functional prognosis of patients at discharge. This delay is also associated with increased rates of institutionalisation at discharge.

El ictus representa en Espa¿na la primera causa de muerte por entidades específicas en mujeres, la primera causa de invalidez en los adultos y supone un enorme coste tanto humano como económico. En los últimos a¿nos se han producido avances importantes tanto en el tratamiento de la fase aguda como en el proceso neurorrehabilitador; sin embargo, continúa sin quedar claro cuál es el momento óptimo en el que debe iniciarse la neurorrehabilitación después de un ictus y cuáles son las consecuencias de retrasar este inicio. El objetivo de este estudio es comprobar el efecto que supone cada día de retraso en el inicio de la neurorrehabilitación en la recuperación funcional y su influencia en la tasa de institucionalización al alta.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo en el que se incluyeron los pacientes ingresados entre abril de 2005 y septiembre de 2008, en la Unidad de Neurorrehabilitación de Ictus (UNRHI) del Hospital Parkwood (Universidad de Western Ontario, Canadá). Se obtuvo la edad, la puntuación FIM al ingreso y al alta, los días entre la aparición del ictus y el ingreso en la Unidad de Neurorrehabilitación y el destino al alta.

ResultadosDespués de ajustar por edad y FIM al ingreso, se encontró una asociación estadísticamente significativa entre la mejoría funcional de los pacientes (ganancia de FIM) y el retraso por cada día en comenzar la rehabilitación. Existe una correlación estadísticamente significativa entre el retraso en iniciar esta terapia y el grado de institucionalización al alta.

ConclusionesPor cada día que se retrase el inicio del tratamiento neurorrehabilitador empeora el pronóstico funcional de los pacientes al alta. Este retraso se relaciona también con una mayor tasa de institucionalización al alta.

Cerebrovascular disease and stroke constitute the leading cause of physical disability and the second cause of dementia in adults according to the World Health Organization (WHO).1,2 Researchers estimate that stroke generates 3%–4% of the total healthcare expenses in developed countries,3,4 amounting to a mean direct cost of 4000 euros per patient in the first three months after the event.5

Neurorehabilitation, understood as the ensemble of methods applied in order to recover neurological functions that have been lost or diminished as the result of cerebral or medullary damage,6 is currently one of the central strategies for treating strokes, in conjunction with early neurological care (admission to the stroke unit and fibrinolytic treatment).

Admitting patients to the stroke unit during the acute phase, followed by admission to specialised neurorehabilitation programmes staffed by multidisciplinary teams dealing exclusively with brain damage, decreases both death rates and sequelae. This improves long-term functional prognosis in these patients.7–9 Some published studies10–12 suggest that after a stroke has occurred, there is a window of time during which the brain is more sensitive to rehabilitation activities, but that this capacity decreases with the passing of time. These data have been corroborated by functional neuroimaging studies,13–18 and both animal19 and human studies.20 Neuroimaging studies have shown how the brain is able to respond to vascular damage beginning in the early phases,13 and that it is able to regain lost functions after a stroke. Animal models have shown that early rehabilitation delivers better functional recovery.21,22 In studies with humans, patients who started rehabilitation in the first 30 days after infarct showed better functional recovery than those who began rehabilitation after the 30-day mark.20

Moreover, better functional recovery is not the only advantage of starting neurorehabilitation early. It has also been established that many of the immediate complications of stroke are linked to remaining immobile, and could therefore be avoided by regaining mobility in the early stages.23

Given this situation, beginning the neurorehabilitation process early is becoming increasingly relevant, especially when we read recent studies that show that beginning rehabilitation treatment in the first 24hours after the event is safe,24,25 contrary to what experts once believed.26

However, all these studies analyse the effects of beginning the neurorehabilitation process within certain “windows of time”, rather than using days as a unit measure. We therefore decided to analyse the effect of delaying neurorehabilitation treatment (using days as our units of time) on the functional prognosis of stroke patients, and any correlations with the institutionalisation of patients upon discharge from the hospital (using “windows of time”).

ObjectiveDetermine the effect on functional recovery of each additional day of delay in neurorehabilitation, and the effect of delaying neurorehabilitation treatment on the percentage of patients institutionalised upon discharge.

Patients and methodsRetrospective study of patients admitted between April 2005 and September 2008 to the Stroke/Neurological Rehabilitation Programme at Parkwood Hospital (Western Ontario University, Canada). Patients were admitted to the rehabilitation programme if they were clinically stable and able to sit in a wheelchair for a minimum of 30min. Once admitted to the programme, they were assessed by a multidisciplinary team consisting of neurologists, physical therapists and internists, nurses, nursing assistants, nutritionists and several therapists (physiotherapists, speech therapists, neuropsychologists, and occupational therapists). A total of 753 patients were selected.

Patients received personalised treatment 5 days a week, during 3hours every day. They also participated in group therapy 2hours every day. For each patient, we recorded age, length of stay in the rehabilitation programme, scores on the Functional Independence Measure scale (FIM)27 upon admission and discharge, gain in FIM score and delay before starting neurorehabilitation treatment.

In order to analyse the influence of a one-day delay in neurorehabilitation treatment, we selected those patients admitted during the first 30 days after the stroke, since it has been postulated that delays in treatment after this initial period do not alter the functional result.20 In order to evaluate factors associated with change in FIM, we performed a linear multiple regression analysis, adjusted for age and FIM upon admission.

To analyse the effect of delaying the start of treatment on the patient's need for institutionalisation upon discharge, we placed the patients in groups according to the window of time in which treatment was begun and used Spearman's rho to conduct a non-parametric correlation study.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 15.0.

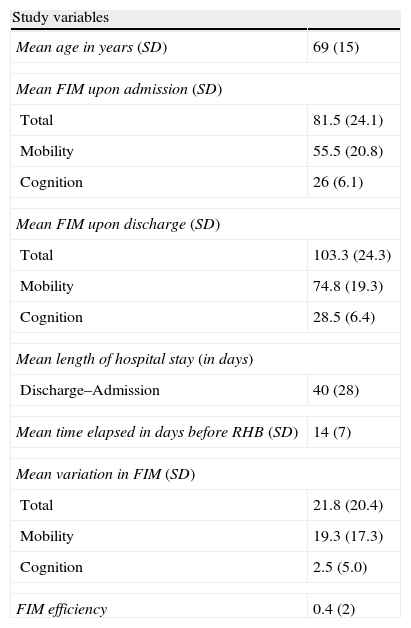

ResultsThe results of the study variables from the first 30 days (N=536, 71% of the total) are shown in Table 1. The mean age of patients included in the study was 69 years. Average length of hospital stay was 40 days and patients started rehabilitation a mean time of 14 days after experiencing stroke (range, 3–29 days). Mean total FIM upon admission was 81.5 points. We noted a mean change in FIM of 21.8 points, mainly due to changes in the FIM mobility score.

Variables recorded. All patients treated during the first 30 days.

| Study variables | |

| Mean age in years (SD) | 69 (15) |

| Mean FIM upon admission (SD) | |

| Total | 81.5 (24.1) |

| Mobility | 55.5 (20.8) |

| Cognition | 26 (6.1) |

| Mean FIM upon discharge (SD) | |

| Total | 103.3 (24.3) |

| Mobility | 74.8 (19.3) |

| Cognition | 28.5 (6.4) |

| Mean length of hospital stay (in days) | |

| Discharge–Admission | 40 (28) |

| Mean time elapsed in days before RHB (SD) | 14 (7) |

| Mean variation in FIM (SD) | |

| Total | 21.8 (20.4) |

| Mobility | 19.3 (17.3) |

| Cognition | 2.5 (5.0) |

| FIM efficiency | 0.4 (2) |

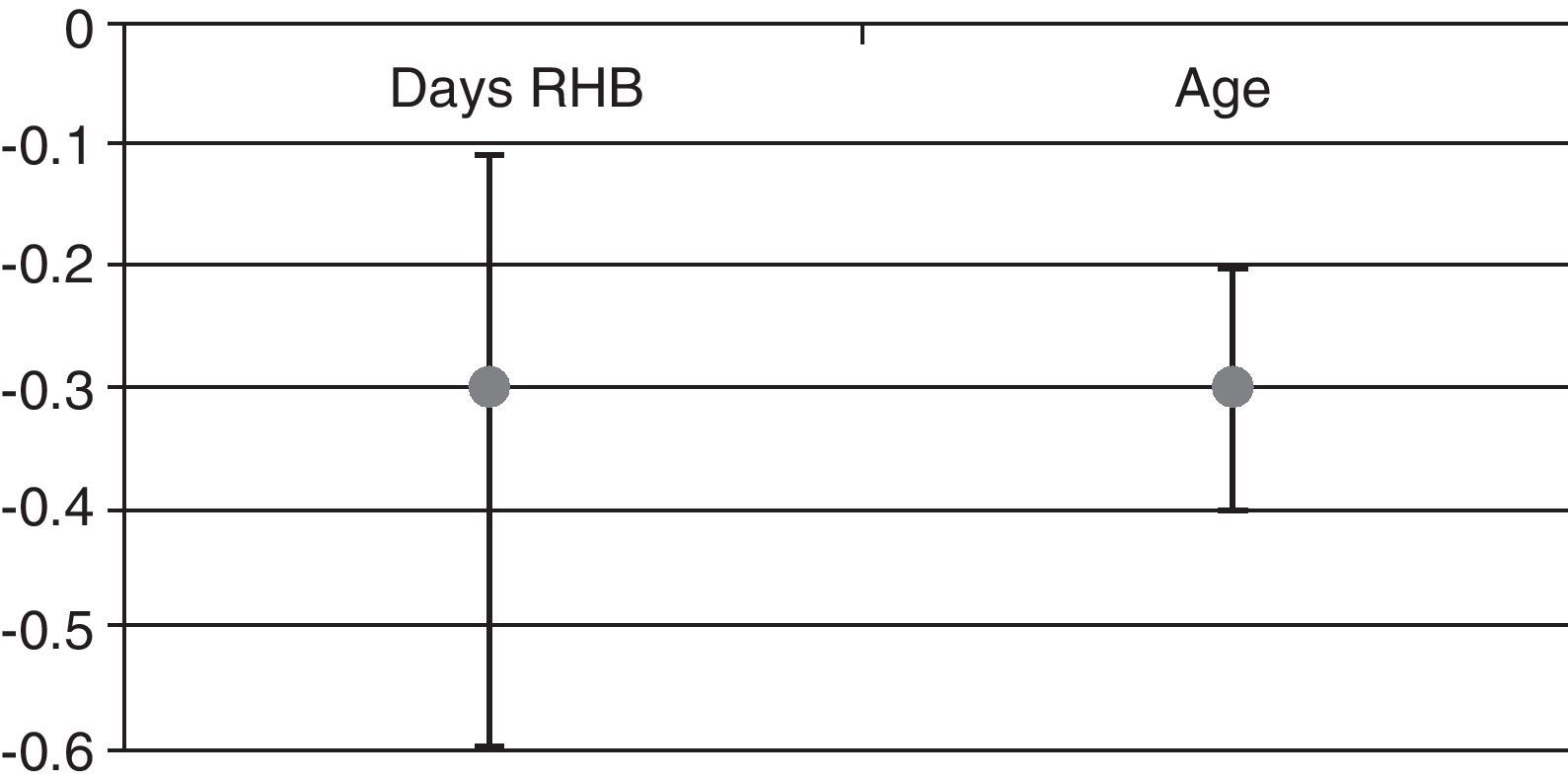

We found that after adjusting for age and baseline FIM, each day of delay in neurorehabilitation treatment entailed a decrease of 0.3 points in the FIM score upon discharge (Fig. 1). We also found a statistically significant association between functional recovery (FIM gain) and the number of days by which beginning rehabilitation was delayed. Additionally, we noticed a statistically significant association between FIM gain and patient age (Fig. 1): the older the patients, the lower the FIM gain.

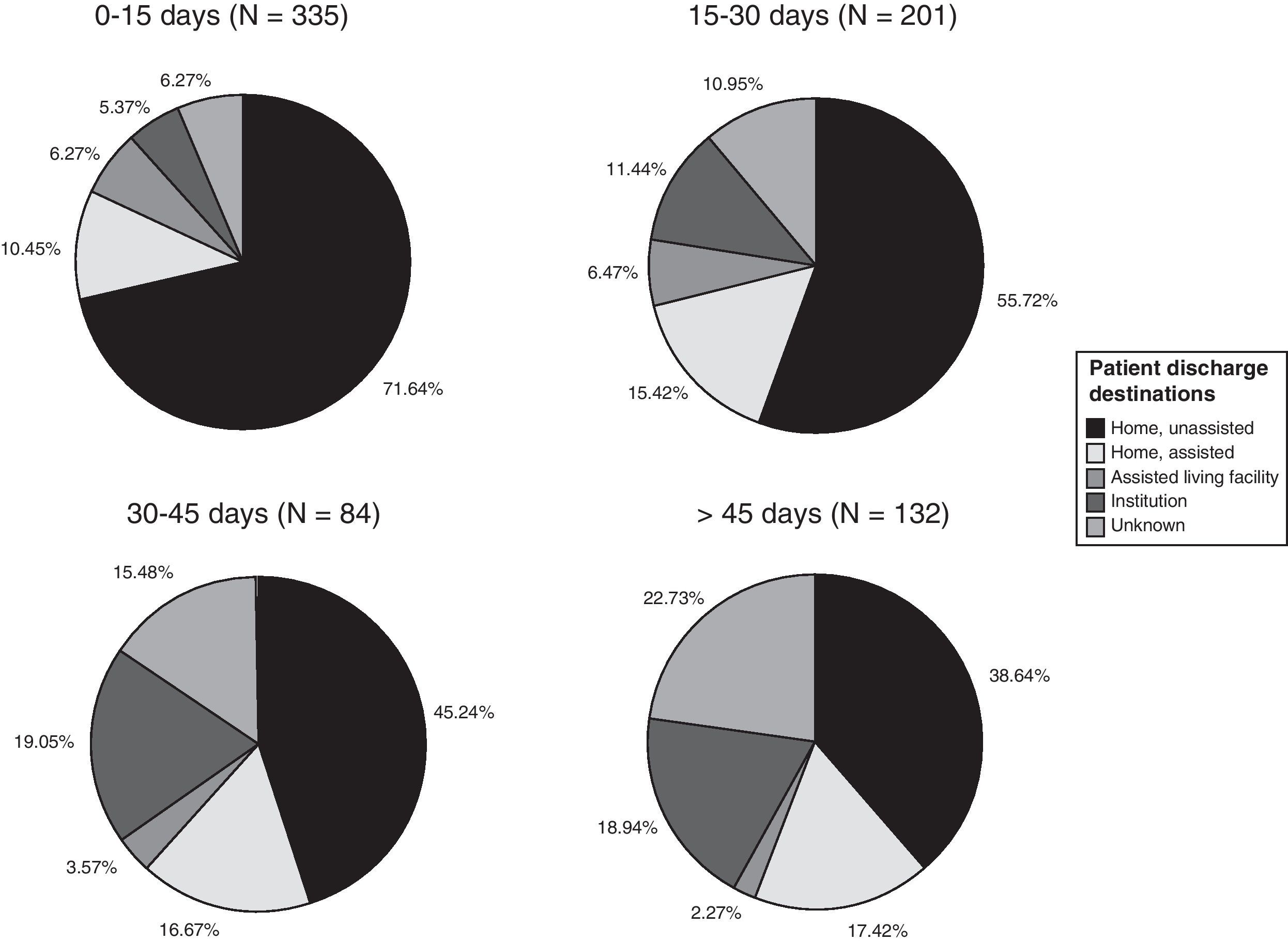

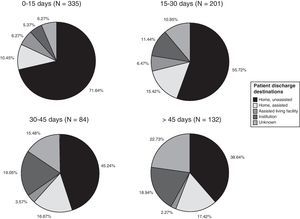

Patient destination upon discharge from the stroke rehabilitation programme is summarised in Fig. 2. This dataset includes data from patients who began rehabilitation more than 30 days after the stroke. Nearly 3 out of 4 patients (72%) returned to their homes upon discharge. We found a statistically significant correlation between delayed onset of therapy and the patient's need for institutionalisation upon discharge. The Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.308 was statistically significant (P<.01) for a 95% confidence level.

Patients’ discharge destinations, broken down by date of starting neurorehabilitation treatment, are shown as percentages in Fig. 2. The percentage of patients sent home with no need for homecare ranges from 71.64% in the group starting treatment in the first 15 days to 38.64% in the group starting treatment after 45 days. The percentage of patients requiring institutionalisation ranges from 5.37% in the former group to 18.94% in the latter group.

DiscussionAs seen in the literature, neurorehabilitation units are fundamental to the functional recovery of stroke patients.28 One of the main advantages of neurorehabilitation is its therapeutic window, which is broader than that of treatments such as fibrinolysis that are used during the acute phase of stroke.29

Results from this study confirm that early neurorehabilitation treatment delivers better functional recovery.30,31 In other words, delayed onset of treatment is associated with a higher level of disability upon discharge. In this study, the earliest onset of treatment was on day 3 after stroke. The potentially harmful effects of beginning therapy during the acute phase were therefore avoided.26

It has also been shown for other types of stroke treatment that taking action early is associated with a better functional prognosis, and that the earlier treatment is provided, the greater the benefit.32 The concept of early treatment should surprise no one. Nevertheless, common practice is far removed from the ideal situation. Patients in stroke units are unattended and inactive25 most of the time; 88% remain in or next to the bed and they spend 60% of their time alone. We notice this tendency regardless of the severity of stroke. Moreover, stroke units need more training in neurorehabilitation and more neurologists involved in rehabilitation programmes.33

The highest FIM gain was recorded for the mobility component, whereas the mean FIM gain for cognition was somewhat lower. This can be attributed to the fact that cognitive recovery requires more time.34 It is likely that the average stay of 40 days is what prevented us from noticing higher cognitive scores.

Early onset of treatment is not only related to functional recovery, but also to a lower rate of institutionalisation, as can be seen in this study. These results coincide with published literature on the subject.35,36 Furthermore, the Post-Stroke Rehabilitation Outcomes Project (PSROP) study37 showed that early neurorehabilitation treatment was associated with shorter hospital stays, and consequently, with lower healthcare costs. This was true for both moderate and severe strokes.

The main limitation of our study is its retrospective design. In addition, it does not differentiate between ischaemic and haemorrhagic strokes and it includes only those stroke cases that meet the criteria for inclusion in the neurorehabilitation programme.

In conclusion, we can state that with every day of delay of neurorehabilitation treatment for stroke patients who are candidates, the poorer the patient's functional recovery will be at the time of discharge from the neurorehabilitation unit. Moreover, delaying the onset of neurorehabilitation in candidates for this treatment is related to a higher institutionalisation rate. Nevertheless, we must consider that these results only allow us to draw conclusions for the short term. Further studies are therefore needed order to determine whether functional recovery gains from early neurorehabilitation treatment remain stable over time, in addition to being detectable upon discharge from the neurorehabilitation unit.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.