Absence seizures due to secondary bilateral synchrony may be a manifestation of frontal seizures, indistinguishable from primary absence epilepsy (PAE), with a different prognosis and control. There are few epidemiological studies on frontal absences (FAE) in the group of absence epilepsy (AE) in children.

ObjectiveTo describe the epidemiology of FAE in childhood and compare the characteristics, clinical evolution, and pharmacological response with PAE.

Patients and methodRetrospective study of cases with AE in children under 14 years of age from 2013 to 2022 in a tertiary hospital. Demographic variables, number, duration and type of associated seizures, frontal EEG focality with and without relation to generalized discharge, pharmacological response and neuroimaging were comparatively studied.

Results94 patients with a median age of 8.6 years (6–10.1 years; 49M/45H) with AE were included. 84% presented exclusively absence seizures. Hyperventilation induced seizures in 94.2%; photoparoxysms present in 5.3%. They showed EEG focus, 63/94 and in 45/94 it was frontal. In 14/94 (14.8%) the frontal focality preceded the critical spike-wave discharge. The bivariate analysis did not show significant differences in age, time until the consultation, psychomotor development/behavior alteration, association of other types of seizures and triggers. The number of absences/days was significantly lower in the EAFs (p = 0.004) and the need for combination therapy was greater in the bivariate (p = 0.005) and multivariate (p = 0.035) analysis.

ConclusionsFAE represents a significant percentage of AE with seizures of identical morphology, age, and duration, although with fewer seizures/day and a worse response to treatment.

Las crisis de ausencia con sincronía bilateral secundaria pueden ser una manifestación de crisis frontales, indistinguibles de la epilepsia ausencias primarias (EAP), con un pronóstico y control diferentes. Existen pocos estudios epidemiológicos sobre epilepsia-ausencias frontales (EAF) en el conjunto de la epilepsia de ausencias (EA) en el niño.

ObjetivoDescribir la epidemiología en la infancia de la EAF y comparar las características, evolución clínica y respuesta farmacológica con las EAP.

Pacientes y métodoEstudio retrospectivo de casos con EA en menores de 14 años de 2013 a 2022 en un hospital terciario. Se estudiaron comparativamente variables demográficas, número, duración y tipo de crisis asociadas, focalidad-EEG frontal con y sin relación a la descarga generalizada, respuesta farmacológica y neuroimagen.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 94 pacientes con una edad mediana de 8,6 años (6–10,1 años; 49M/45H) con EA. El 84% presentaba exclusivamente crisis de ausencias. La hiperventilación indujo crisis en el 94.2%; fotoparoxismos presentes en el 5.3%. Mostraron focalidad EEG, 63/94 y en 45/94 ésta era frontal. En 14/94 (14.8%) la focalidad frontal precedía a la descarga punta-onda crítica. El análisis bivariante no mostró diferencias significativas en edad, tiempo hasta la consulta, alteración del desarrollo psicomotor/comportamiento, asociación de otro tipo de crisis y desencadenantes. El número de ausencias/día fue significativamente menor en las EAFs (p = 0,004) y fue mayor la necesidad de biterapia al análisis bivariante (p = 0.005) y multivariante (p = 0.035).

ConclusionesLa EAF supone un porcentaje importante de la epilepsia de ausencias con crisis de idéntica morfología, edad y duración, aunque con menos crisis/día y peor respuesta al tratamiento.

Absence seizures with secondary bilateral synchrony (SBS) may represent a form of generalisation originating in persistent foci, typically located in frontal regions, and may be clinically indistinguishable from primary absence seizures, which classically display primary bilateral synchrony (PBS) on surface EEG. The concept of SBS has long been described and discussed. The Wada test is considered the gold standard for its recognition,1,2 revealing suppression of spike-and-wave discharges, decreased beta-wave activity in the epileptogenic focus, and the appearance or persistence of focal paroxysms.

Frontal absence epilepsy (FAE) is characterised by a typically frontal focus that becomes generalised in predisposed individuals3 in the form of a bilateral synchrony pattern,4–6 which is referred to as secondary to differentiate it from the PBS observed in idiopathic childhood and adolescence absence epilepsies. This pattern is also described in patients displaying a temporal focus near the frontal cortex. From a semiological perspective, both absence epilepsy syndromes are characterised by short episodes of absences, which occur multiple times per day and may be triggered by hyperventilation. Patients may also present other types of focal seizures, making clinical diagnosis challenging. However, their prognosis and pharmacological treatment seem to be different.7,8

From a neurophysiological viewpoint, no formal consensus has been established on the definition of SBS. Several criteria have been proposed, including presence of a persistent frontal focus with a tendency to generalisation, onset at least 2 seconds prior to the generalised discharge, and interhemispheric asymmetry in voltage and/or morphology on EEG. These findings are more frequently observed during NREM sleep; therefore, a sleep EEG may be needed when SBS is suspected based on epilepsy course or treatment response.

Few studies have addressed childhood FAE, as it is a poorly recognised condition that is difficult to classify nosologically and presents clinical and EEG overlap with primary absence epilepsy (PAE). This study aims to determine the epidemiology of FAE among childhood absence epilepsies, and to compare its clinical presentation, course, and treatment.

Patients and methodsWe conducted a retrospective, observational, descriptive analysis of all patients under the age of 14 years diagnosed with typical absence seizures at a tertiary referral hospital between 2013 and 2022. The centre uses an electronic medical record system and has a dedicated childhood epilepsy team. Data were gathered for the following variables: sex, age, follow-up time, number and duration of seizures, presence of associated focal or tonic-clonic seizures, frontal EEG focus with or without relation to the onset of the generalised discharge, neuroimaging studies, psychomotor development, behavioural and learning alterations, treatment, and treatment response. Daily seizure frequency is based on caregivers’ reports; therefore, we are aware that the real number of seizures per day is likely to be higher. Given the retrospective nature of the study, data on psychomotor development during the first 4 years of life is based on the Haizea-Llevant/Denver scale, the standard tool used at primary care centres in our setting. Similarly, behavioural and learning disorders were established based on special educational needs (therapeutic pedagogy, auditory-verbal therapy, and curriculum adaptation).

SBS was defined as the presence, at any point in the surface EEG recording, of persistent focal activity with a tendency to generalisation, occurring at least 2 seconds before the generalised spike-and-wave discharge.1 For comparisons, patients were classified as having PAE with PBS or FAE with SBS. Dichotomous qualitative variables were analysed with the Fisher exact test or the chi-square test. Variables with P-values < .20 were included in the multivariate analysis. Quantitative variables were compared using the t test.

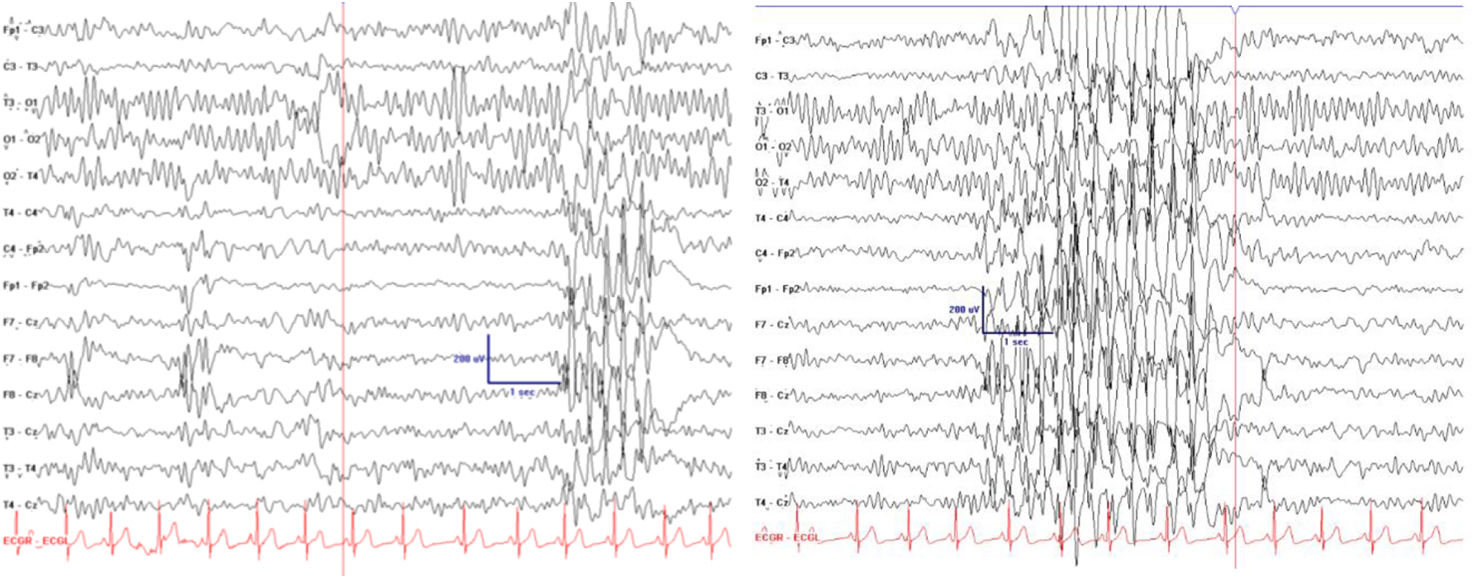

ResultsOur sample included 94 patients (45 boys and 49 girls) with typical absence seizures, with a median age of epilepsy onset of 8.6 years (Q1-Q3: 6-10.1). Eighty-four percent of patients presented exclusively absence seizures. In 14 cases (14.8%), frontal activity preceded the spike-and-wave discharge (Fig. 1); these patients were classified as having FAE with SBS. MRI studies were performed in 54 patients, yielding normal findings in all cases. Regarding EEG, the hyperventilation manoeuvre triggered seizures in 94.2% of patients, with no significant differences between the FAE and PAE groups. Intermittent photic stimulation induced a photoparoxysmal response in 5.3% of patients. Focal paroxysmal activity was observed in 63 patients, with 45 showing activity localised in the frontal lobe.

Pharmacological treatment achieved initial seizure control in 79.8% of patients. The most frequently used drug was valproic acid (76.6%; mean dose of 32 mg/kg/day [SD: 8]), followed by ethosuximide (36.2%; mean dose of 28 mg/kg/day [7]) and lamotrigine (24.5%; mean dose of 4.7 mg/kg/day [0.6]).

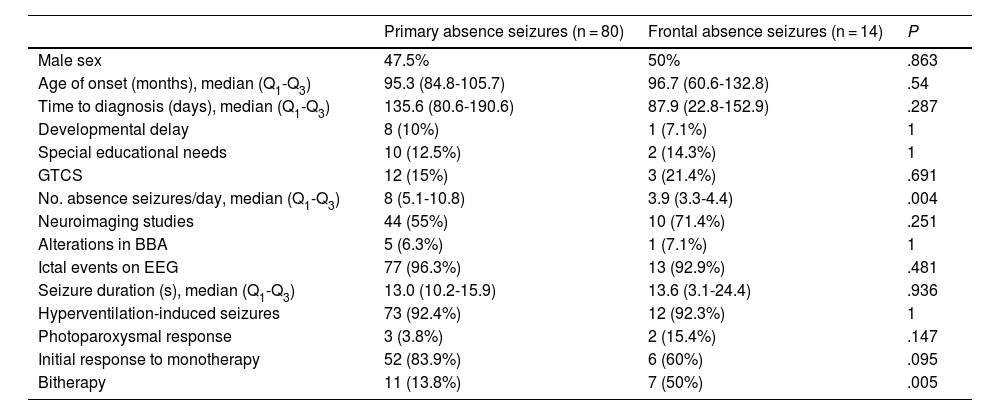

The bivariate analysis (Table 1) showed no statistically significant differences in age of epilepsy onset, time to consultation, psychomotor development, behavioural or learning problems, association with other seizure types, or triggering manoeuvres on EEG.

Statistical comparison of variables between children with focal absence seizures and those with primary absence seizures. BBA: background bioelectrical activity; EEG: electroencephalography; GTCS: generalised tonic-clonic seizures; Q1-Q3: quartiles 1 and 3.

| Primary absence seizures (n = 80) | Frontal absence seizures (n = 14) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 47.5% | 50% | .863 |

| Age of onset (months), median (Q1-Q3) | 95.3 (84.8-105.7) | 96.7 (60.6-132.8) | .54 |

| Time to diagnosis (days), median (Q1-Q3) | 135.6 (80.6-190.6) | 87.9 (22.8-152.9) | .287 |

| Developmental delay | 8 (10%) | 1 (7.1%) | 1 |

| Special educational needs | 10 (12.5%) | 2 (14.3%) | 1 |

| GTCS | 12 (15%) | 3 (21.4%) | .691 |

| No. absence seizures/day, median (Q1-Q3) | 8 (5.1-10.8) | 3.9 (3.3-4.4) | .004 |

| Neuroimaging studies | 44 (55%) | 10 (71.4%) | .251 |

| Alterations in BBA | 5 (6.3%) | 1 (7.1%) | 1 |

| Ictal events on EEG | 77 (96.3%) | 13 (92.9%) | .481 |

| Seizure duration (s), median (Q1-Q3) | 13.0 (10.2-15.9) | 13.6 (3.1-24.4) | .936 |

| Hyperventilation-induced seizures | 73 (92.4%) | 12 (92.3%) | 1 |

| Photoparoxysmal response | 3 (3.8%) | 2 (15.4%) | .147 |

| Initial response to monotherapy | 52 (83.9%) | 6 (60%) | .095 |

| Bitherapy | 11 (13.8%) | 7 (50%) | .005 |

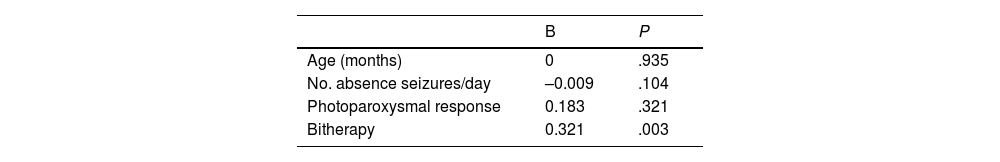

Some variables behaved differently between groups. For instance, the number of absence seizures per day reported by caregivers was significantly lower in the FAE group (P = .004). Although this variable does not precisely reflect the real number of seizures experienced by patients, it was considered comparable between groups. Furthermore, bivariate analysis revealed that bitherapy was more frequent among patients with FAE (P = .005); this association remained significant in the multivariate analysis (P = .003), which also included age, number of absence seizures per day, and hyperventilation (Table 2). The most frequent drug combination in the FAE group was valproic acid plus ethosuximide (n = 9). In 5 patients, seizures were initially treated with valproic acid, and ethosuximide was added subsequently, whereas in the remaining 4 patients, treatment was started with ethosuximide, subsequently adding valproic acid. Two patients also received lamotrigine as a third line of treatment, but the drug did not achieve full seizure control.

DiscussionSeizures originating in the frontal lobe are highly variable from a semiological viewpoint, and surface EEG recordings are frequently difficult to interpret and may be insufficiently sensitive. Therefore, foci that can generalise in different ways may occasionally go undetected on EEG. One such pathway is via the thalamo-cortical circuit in the form of SBS,9 which, in predisposed individuals, is associated with alterations in frontal lobe fibre tracts.3 Regarding generalised interictal epileptiform discharges, Tükel and Jasper1 demonstrated that focal parasagittal lesions may cause bilateral slow-wave discharges due to SBS. It is also possible for a frontal focus to appear distant from a generalised discharge in some parts of the EEG recording, while clearly preceding generalisation in others.5

Patients with FAE presented significantly poorer treatment response, often requiring polytherapy, and significantly fewer seizures per day than those with PAE. In some cases, the diagnosis of FAE was reached progressively, with the typical characteristics of SBS not initially being observed in some patients; their detection on surface EEG can be elusive and challenging. Propagation of discharges originating in the frontal lobe to contralateral homologous regions and ipsilateral temporal regions can hinder their localisation, as rapid propagation of the discharge may conceal its focal onset.5 While PAE may display similar patterns, it is more frequent for discharges to originate inconsistently in non-frontal areas.5,10

The presence of focal EEG activity in patients with absence epilepsy is widely recognised, and is most common in poorly controlled cases; this is also true for classic forms of PAE.10 In our series, patients with FAE required bitherapy significantly more frequently than those with PAE; nevertheless, pharmacological treatment achieved acceptable seizure control in most cases. In previous studies on FAE, Lagae and colleagues identified a subgroup of children whose absences were refractory to traditional antiseizure drugs and showed more marked learning and behavioural problems. In these children, generalised epileptic discharges originated from a focus in the frontal region and subsequently presented the classic generalised spike-and-wave pattern.7,8 In our series, this group of patients represents a substantial 14.8% of all cases of absence seizures, and their semiology resembled that of PAE. No differences were observed in neuroimaging findings; therefore, we may assume that cases with persistent foci may be due to dysplasia or small lesions. The proportion of children presenting behavioural and learning problems was not significantly greater in the FAE group than in the PAE group, which we attribute to reasonably good seizure control; in any case, the sample size may be too small to draw robust conclusions. Frontal seizures in general may be associated with varying degrees of cognitive involvement, depending on the degree of treatment resistance; frontal absence seizures are ultimately frontal seizures with bilateral progression manifesting as absences.

There is longstanding evidence that a single surface EEG recording may show both generalised focal-onset discharges and diffuse discharges with no clearly identifiable focal onset.11 Certain frequent characteristics may help to differentiate SBS: persistent focal activity with a tendency to generalisation and/or preceding a generalised discharge, frequencies between 2.5 and 4 Hz, irregular spike-and-wave morphology, and interhemispheric asymmetry.1 The Wada test remains the reference technique, and should be performed in refractory patients potentially eligible for epilepsy surgery.

In our sample, all neuroimaging results were normal. The indication for MRI in refractory cases seems to be justified, despite the limited findings. In contrast, performing MRI in patients with absence seizures based solely on the presence of focal EEG activity does not seem to be efficient from a clinical viewpoint.

One limitation of our study is the fact that the anatomical study of the epileptogenic focus did not employ more sensitive imaging techniques, such as 3T MRI, SPECT/PET, or DTI tractography to assess the connectivity of the regions involved. Furthermore, long-duration video-EEG recordings and long-term follow-up data were not available for all patients, which prevented us from assessing progression in both groups. Likewise, the retrospective evaluation of learning, behaviour, and psychomotor development was based on very basic parameters. Further prospective studies should include these variables to better characterise the pathophysiology of FAE.

ConclusionsIn our sample, FAE accounted for up to 14% of all cases of typical childhood absence epilepsy, with seizures showing similar semiology, duration, and age of presentation, but with lower daily frequency and poorer treatment response. FAE should be suspected in patients with absence seizures who do not respond to monotherapy; sleep EEG should always be performed in these cases to identify features suggestive of SBS.

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from any public, commercial, or non-profit organisation.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.