Strategic learning self-efficacy reflects the confidence of managers in their ability to learn from the outcomes of past strategic decisions and apply that knowledge to new decisions. This research examines the relationship between strategic learning self-efficacy and a firm's industry-adjusted sales growth rate and specifies strategic decision-making style (ranging from autocratic to participative) and environmental dynamism (ranging from stable to dynamic) as contingency factors that affect this relationship. Primary and secondary data collected from 101 manufacturing firms were used to test hypothesized relationships. Results indicate that strategic learning self-efficacy is not significantly related to firm growth as a main effect. However, strategic decision-making style and environmental dynamism were both found to negatively moderate the relationship between strategic learning self-efficacy and firm growth. Moreover, strategic learning self-efficacy, strategic decision-making style, and environmental dynamism were found to have a three-way interactive effect on firm growth. Thus, dimensions of the learning context strongly influence the degree to which strategic learning self-efficacy is associated with firm growth.

Strategic learning can be defined as the process through which a firm acquires knowledge that leads to change in the firm's strategy (Anderson et al., 2009; Battisti et al., 2019; Pietersen, 2002; Thomas et al., 2001). Of course, change per se is not inherent to learning. A strategy's enactment may result in the acquisition of knowledge that leads to strategic persistence, not strategic change. Nonetheless—perhaps because of the empirical challenges associated with inferring when a firm's strategy-related knowledge stock has increased—the strategic learning literature often treats the exhibition of strategic change as evidence that strategic learning has occurred. Consistent with this observation, Voronov and Yorks (2005, p. 14) state that strategic learning involves “a process of continuously crafting and reformulating strategies.” Likewise, Ambrosini and Bowman (2005, p. 493) note that strategic learning “relates directly to the key management question of how organizations change their strategy to develop and maintain their competitive advantage.”

Research into the phenomenon of strategic learning has been mostly anecdotal in nature, with the presence of strategic learning often being inferred by the researcher within the context of a case study or a small sample of firms (e.g., Ambrosini & Bowman, 2005; Anderson et al., 2009; Kuwada, 1998; Sirén, 2017; Sirén & Kohtamäki, 2016). The principal focus of one stream of strategic learning research has been the process of strategic learning (Shu et al., 2019; Wyer et al., 2000). This research has sought to clarify how the phenomenon of strategic learning is manifest in organizational settings. Examples of research within this stream include Pascale's (1996) description of the Honda Motor Company's introduction of small-displacement motorcycles into the U.S. market, along with Crossan and Berdrow's (2003) study of strategic renewal at Canada Post Corporation.

A second strategic learning research focus is the identification of managerial, organizational, or environmental factors that promote the occurrence of strategic learning (e.g., Boussouara & Deakins, 2000; Satyanarayana et al., 2022; Schröder et al., 2021). In this second research stream, strategic learning is implicitly treated as the outcome of circumstantial conditions. Understanding the unique qualities of these conditions is the principal purpose of this second research stream. Examples include Barr's (1998) study of how managerial interpretations of external events developed as a basis for strategic learning and change in six pharmaceutical companies, along with the study by Thomas et al. (2001) of the organizational practices and processes that led to strategic learning at The Center for Army Lessons Learned.

Underrepresented in research on strategic learning are studies that seek to identify the contexts in which strategic learning connects most strongly to desirable organizational performance outcomes (Antunes & Pinheiro, 2020). Research has largely ignored the possibility that strategic learning's promise as a driver of organizational performance is affected by the circumstances under which the learning takes place. (There are a few exceptions to this, such as the simulation-based study by Lant and Mezias (1990) of the value of learning under different levels of environmental ambiguity.) Therefore, a knowledge void exists in strategic learning literature. Addressing this knowledge void is important, because strategic learning necessarily takes place within a context, and—consistent with the knowledge-based view of the firm (Grant, 1996) —context affects the extent to which knowledge-based assets can be generated through organizational learning. Moreover, consistent with the tenets of situated learning theory (Brown et al., 1989; Lave & Wenger, 1991), attributes of the learning context affect learning outcomes (Do et al., 2022).

The purpose of this research is to investigate the possible moderating effects of two theoretically important aspects of a firm's learning context—namely, strategic decision-making style and environmental dynamism—on the relationship between strategic learning self-efficacy and the critical firm performance outcome of sales growth rate. Sales growth rate is adopted as a performance indicator, because it reflects the effectiveness with which firms adapt their strategies to the conditions of their environments (Kiss & Barr, 2015; Schindehutte & Morris, 2001). Strategic decision-making style—herein conceptualized along the autocratic-to-participative dimension—has long been observed to correspond with one's ability to learn and receptiveness to learning (e.g., Cooper, 2014; Scott-Ladd & Chan, 2004). Environmental dynamism—herein conceptualized along the stable-to-dynamic dimension—is often discussed as necessitating learning and possibly diminishing the value of prior knowledge (e.g., Do et al., 2022; Oh & Kim, 2022). Joint consideration of decision-making style and environmental dynamism—as moderators of the strategic learning self-efficacy-firm sales growth rate relationship—recognizes that learning effectiveness is driven by both internal, organizational factors (e.g., Abubakar et al., 2019; Do et al., 2022) and external, environmental factors (e.g., Kamasak, Yavuz & Altuntas, 2016; Mohammad, 2019). Both types of factors are important contingencies in models of learning effectiveness, yet the interdependencies of internal and external contingencies remain largely unexplored in current strategic learning research.

Theory and hypothesesThe concept of strategic learning self-efficacyIn social cognitive theory, Wood and Bandura (1989, p. 364) define self-efficacy as “people's beliefs in their capabilities to mobilize the motivation, cognitive resources, and courses of action needed to exercise control over events in their lives.” Self-efficacy also can be more narrowly defined as confidence in one's ability to do a specific task, such as strategic learning (Audia et al., 2000). The construct of strategic learning self-efficacy reflects the belief of top managers that they can evaluate past strategic decisions and the associated outcomes and enact changes to firm strategy by employing what was learned. Strategic learning self-efficacy is herein defined as “managers’ confidence in their ability to interpret the outcomes from past decisions and modify future tactics based on what was learned from past behavior” (Garrett et al., 2009, p. 784).

The knowledge-based view of the firm recognizes that competitive success is contingent upon a firm's ability to develop new knowledge-based assets through organizational learning processes (Grant, 1996). Empirical evidence suggests that the strength of a firm's learning orientation—of which strategic learning would constitute one component—is positively associated with firm growth (Baker & Sinkula, 1999; Baker et al., 2022; Battisti et al., 2019). The observed relationship between organizational learning and firm growth might be attributable to the fact that learning facilitates the product-market opportunity recognition process, and the pursuit of such opportunities drives firm growth (Lumpkin & Lichtenstein, 2005). Likewise, the more targeted phenomenon of strategic learning might be positively associated with firm growth, because strategic learning often manifests through strategic changes involving product-market and competitive innovations (Leavy, 1998). Such innovations can place the firm on new or renewed growth trajectories.

Nonetheless, Crossan and Berdrow (2003, p. 1089) observe that “research on organizational learning is not without its problems. For example, practitioner-focused, learning research has left practitioners and many researchers with a very normative view of organizational learning as an innately positive phenomenon (Baker et al., 2022). Allowing for the possibility that organizational learning may not be utopian enables us to take a more critical view of organizational learning and helps reveal undiscovered aspects of the process.” These same arguments might be made with respect to the process through which firms acquire knowledge that leads to strategic change (i.e., the strategic learning process). Specifically, although strategic learning has often been discussed as if it is an innately productive process (see Abubakar et al., 2019; Leavy, 1998), there may be nothing inherent to strategic learning that necessarily promotes firm performance. Relatedly, the perception that firms are efficacious in their strategic learning may be only weakly tied to firm performance. Allowing for the possibility that strategic learning is not a managerial panacea might redirect research toward identifying factors that amplify or attenuate strategic learning's effectiveness.

There are at least two reasons why adopting a more neutral posture with respect to the value of strategic learning self-efficacy may be advisable. First, as argued by Huber (1991), learning per se does not necessarily produce positive results. This is because what is learned will sometimes be erroneous. When this is the case, the strategic changes enacted within the strategic learning process will be driven by flawed “lessons,” and, therefore, they will lead to unsatisfactory performance outcomes (Madsen & Desai, 2010). Second, strategic changes are often prompted by a performance shortfall (Ketchen & Palmer, 1999). On this point, in a discussion of the strategic learning process, Lant and Mezias (1990, p. 149) argue that “change in [strategic] behavior is more likely when performance is below aspiration level or perceived as failure.” Of note, the size of a performance shortfall might be required to be significant before management feels compelled to implement strategic changes. As argued by Barr (1998, p. 663), “because strategic change involves shifts in resources allocations that are expensive and difficult, if not impossible to reverse, managers are unlikely to make any significant changes in strategic action until they are certain such changes are required.” Thus, firms that report high strategic learning self-efficacy will often be starting off with an unsatisfactory level of performance as their “base.”

In short, the relationship between strategic learning and firm performance presented in the relevant literature (e.g., Grant & Gnyawali, 1996; Pietersen, 2002; Voronov & Yorks, 2005) may not be as positive in practice as in theory. Consequently, we offer the following null hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (null). Strategic learning self-efficacy does not exhibit a strong relationship with firm sales growth rate.

Notably, a strong relationship need not exist between two variables for their relationship to be moderated (see, for example, Aiken & West, 1991; Brambor et al., 2006), with a positive relationship between two variables under one moderator condition being countered by a negative relationship between those variables under another condition. In particular, the direction of the relationship between strategic learning self-efficacy and firm sales growth rate might be contextually determined based on the strategic decision-making processes employed and the conditions of the firm's external environment. The following sections posit that decision-making style and environmental dynamism level are two elements of the learning context that influence the strategic learning self-efficacy-firm sales growth rate relationship.

Moderators of the strategic learning self-efficacy – firm sales growth rate relationshipStrategic decision-making stylePast research has shown decision-making style to be an important but seldom explored influence on the organizational performance outcomes associated with learning and knowledge management practices (Abubakar et al., 2019). The current research focuses on strategic decision-making style, defined for the research purposes of this article as “the extent to which a firm's major operating and strategic decisions are made through consensus-seeking vs. individualistic or autocratic processes by the formally responsible executive” (Covin et al., 2006, p. 59) Thus, style of strategic decision-making is conceptualized along a low-to-high “participativeness” dimension, ranging from autocratic decision-making (in which decisions are made by single individuals with responsibility in the decision area) to participative decision-making (in which multiple individuals are involved in consensus-oriented decision-making). The choice of a decision-making research construct involving consensus-seeking behavior is based on the possibility that such behavior—that is, convincing multiple individuals to agree that specific strategic decisions should be actively pursued—is relevant to the successful enactment of strategic learning. As argued by Thomas et al. (2001, p. 339), “strategic learning involves accessing the insights of experts throughout the organization to promote a rich extended dialogue and provide multiple interpretations of learning events.”

Nonetheless, it is not clear that a participative approach to strategic decision-making will generally lead to successful strategic learning outcomes. As argued previously, the exhibition of strategic learning is typically induced by less-than-satisfactory firm performance; this, in turn, drives strategic change. Hendry (2000, p. 963) asserts that “strategic managers may not always—or often—have the luxury of being able to build consensus to the point of organizational commitment before circumstances determine the need for action.” Thus, when the need for strategic change is most pressing—that is, under conditions of less-than-satisfactory firm performance outcomes—the employment of consensus-seeking approaches to strategic decision-making may prolong the decision process and thereby delay the implementation of needed strategic change. Moreover, involving multiple individuals in the strategic decision-making process often results in the emergence of negotiated belief structures (Walsh & Fahey, 1986) that can inhibit a firm's willingness and ability to embrace anything more than minor strategic changes. However, insignificant deviations from past strategies are unlikely to create significant improvements in firm performance (Lant et al., 1992).

It is particularly significant that a more autocratic strategic decision-making style may strengthen the relationship between strategic learning self-efficacy and firm growth. Under autocratic management, the individuals responsible for the content of strategic change decisions will make those decisions based on their uncompromised interpretations of the relationships between past strategic actions and their outcomes (Iqbal, Anwar & Haider, 2015). As observed by Mintzberg (1973), firms that successfully enact the most significant strategic changes and grow—creating indicators that effective strategic learning has occurred—are often managed in the entrepreneurial mode, wherein autocratic strategists lead their organizations with clear, singular visions regarding desired organizational objectives and the means for obtaining them.

In short, the following hypothesis is offered:

Hypothesis 2 Strategic learning self-efficacy is more positively related to firm sales growth rate when major operating and strategic decisions are made in autocratic manners, as opposed to when those decisions are made in more participative manners.

Although the construct of environmental dynamism can encompass multiple aspects of change in a firm's external environment (e.g., technological changes, market growth rate changes), it is generally acknowledged that change per se does not render environments challenging from a strategic management perspective. Rather, it is the predictability of strategically relevant change that can preclude managers from knowing whether they have made the correct strategic choices (Kamasak et al., 2017; Sharfman & Dean, 1991; Thompson, 1967). As conceptualized in the current context, environmental dynamism refers to the extent to which key strategic considerations in the external environment (e.g., the actions of competitors, product demand, and customer preferences) are easily and accurately predicted (Miller & Friesen, 1982). Defined as such, a dynamic environment is one in which key strategic considerations in the external environment change in relatively unpredictable ways. Meanwhile, a stable environment (i.e., low dynamism) is one in which key strategic considerations in the external environment do not change or change in relatively predictable ways. A high level of dynamism is often assumed to necessitate the exhibition of strategic learning, because firm strategy often must be adapted to fit clarifying or evolving environmental circumstances (e.g., Barr, 1998; Cingöz & Akdoğan, 2013; Dutton et al., 1983; Lant et al., 1992; Mohammad, 2019). Examples of well-known firms operating in high dynamism environments include Google, Amazon, and OpenAI (ChatGPT). Examples of well-known firms operating in relatively low dynamism or stable environments include Walmart, Bank of America, and Coca- Cola.

The relative predictability of stable environments is a quality that may enhance the effectiveness of any strategic learning that takes place therein (Do et al., 2022; Kamasak et al., 2017; Stieglitz et al., 2016). Specifically, there are at least two reasons why strategic learning self-efficacy should be most positively associated with firm growth under conditions of environmental stability. First, the lessons learned in stable environments will be based on knowledge gleaned from events and circumstances that are relatively unambiguous and knowable in character (Haarhaus & Liening, 2020). Therefore, the knowledge that accrues with strategic learning in stable environments should exhibit greater accuracy and overall quality. Second, because of the relative predictability of stable environments, the lessons learned therein will more likely remain relevant across time. As such, any strategic changes that are enacted will be made in response to environmental conditions continuing to operate and remain strategically relevant to the firm (Wu et al., 2023).

Research by Lant and Mezias (1990) is consistent with the aforementioned arguments. Based on a simulation study of strategic learning under various states of environmental ambiguity, Lant and Mezias (1990) conclude that managers are more likely to successfully learn and make strategic changes that improve performance (operationalized in terms of various criteria, including firm growth) when their firms operate in unambiguous environments, as opposed to when they operate in ambiguous environments. The researchers’ rationale is that “the very nature of [environmental] ambiguity makes it difficult to detect valid signal from noise” (p. 172), and detecting valid signals is necessary for successful strategic learning to occur. Significantly, dynamic environments tend to exhibit greater ambiguity than stable environments (Ogilvie, 1998; Sharfman & Dean, 1991). Therefore, the research of Lant and Mezias (1990) and the preceding arguments suggest the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 Strategic learning self-efficacy is more positively related to sales growth rate among firms operating in stable environments, as opposed to among firms operating in more dynamic environments.

It is anticipated that strategic learning self-efficacy, strategic decision-making style, and environmental dynamism will collectively and interactively predict firm sales growth rate. Specifically, there are reasons to expect that participative strategic decision-making styles will have a more positive moderating effect on the relationship between strategic learning self-efficacy and sales growth rate when the environment is dynamic. On the other hand, autocratic strategic decision-making styles may have a more positive moderating effect on the relationship between strategic learning and sales growth rate when the environment is stable.

Considering first the possible influence of participative management on the efficacy of strategic learning in dynamic environments, research suggests that the information gathered through participatory processes will be of greatest value as input to decision-making when the decision environment is characterized by uncertainty (e.g., Burns & Stalker, 1961; Thompson, 1967). The enhanced value of participative decision-making processes under conditions of uncertainty is said to exist, in part, because environmental uncertainty “requires decentralization of authority down the hierarchy to relieve the managerial burden of top managers” (Miller, 1992, p. 162), and the adoption of participatory management practices is one mechanism for decentralizing authority. Most significantly, when participative decision-making processes are employed in contexts characterized by uncertainty (such as in dynamic environments), the informational input to strategic decisions will often be of greater overall quality by virtue of its enhanced scope and/or depth (Wu et al., 2023). Therefore, high quality input to the decision-making process may strengthen the relationship between strategic learning self-efficacy and firm performance by increasing the likelihood that any strategic lessons learned are valid.

By contrast to the preceding observations, autocratic management may have a more positive influence on the strategic learning self-efficacy-sales growth rate relationship in stable environments. Such environments pose fewer challenges to managers, because their relative predictability renders them more easily and accurately understood for decision-making purposes. Consistent with the arguments of Vroom and Yetton (1973), when senior executives have greater confidence in their decision-relevant knowledge, they rely less on others for decision input and manage in more autocratic fashions. Moreover, any strategic changes enacted by autocratic managers in stable environments will more likely reflect accurate interpretations of environmental exigencies and well-understood relationships between strategic actions and outcomes. In this case strategic learning self-efficacy should most positively affect firm performance.

In short, it is hypothesized: Hypothesis 4. Strategic learning self-efficacy, strategic decision-making style, and environmental dynamism have a three-way interaction effect on firm sales growth rate such that: (a) when the strategic decision-making style is participative, strategic learning self-efficacy has a more positive relationship with sales growth rate among firms operating in dynamic environments, as opposed to among firms operating in more stable environments; and (b) when the strategic decision-making style is autocratic, strategic learning self-efficacy has a more positive relationship with sales growth rate among firms operating in stable environments, as opposed to among firms operating in more dynamic environments.

The employed dataset consists of manufacturing-based firms in the Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia tri-state area of the United States. Data were collected through collaboration with a regional economic development organization, the Southwestern Pennsylvania Industrial Resource Center (SPIRC). The SPIRC business census records were examined to identify a sample of 418 firms that were nondiversified business units, with a minimum of 50 employees. Only single (or primary) industry firms were included in the sample, because reported strategic learning self-efficacy might be expected to vary across firms with diverse product lines or business units. The sample was restricted to manufacturing-based firms; firms in other industries—such as agriculture, mining, wholesale, and retail trade—were excluded from the sample as a means of controlling for industry-specific influences on sales growth rate. Firm size was a concern, because small firms—meaning those with fewer than 50 employees—may not have a sufficiently large organizational hierarchy to give meaning to the scale items used to assess strategic decision-making style. Moreover, research has indicated that smaller firms tend to have more autocratic strategic decision processes (e.g., Erez & Rim, 1982), with management in the authoritarian “entrepreneurial mode” being common among such businesses (Mintzberg, 1973).

The senior-most executive in each of the 418 firms received 2 questionnaires. The senior-most executive served as the primary respondent and was asked to designate a secondary respondent, who was a colleague working at the senior executive level of the firm. The secondary respondent was to be selected based on a combination of knowledge of the business and direct involvement in the strategic process. The data provided by the secondary respondent were used strictly for corroboration purposes. Those executives who did not respond to the initial request received a telephone call reminder 1 month after the initial mailing. Data furnished by the secondary respondents supported the treatment of the primary respondents as key informants in this research. No significant differences were identified in a series of t-tests comparing the mean scores provided by the primary and secondary respondents on each research variable. This suggested that across the sample, there was no discernible measurement bias attributable to which respondent completed the survey.

A total of 170 usable responses were received (from 115 primary and 55 secondary respondents), representing 115 unique firms. The organizational response rate was 27.5 % (115/418). This is well within—if not above—the typical response range of survey-based, organizational-level research in the strategic management domain (e.g., Kamasak et al., 2016, 2017; Santos-Vijande et al., 2012; Wilden et al., 2013). This study focused on 101 of the 115 firms that returned the questionnaire. The 14 firms excluded from the current research were omitted because: (a) necessary industry data were not available for these firms; (b) the firms failed to furnish essential performance data, and these data could not be found in secondary sources; or (c) the firms’ sizes had dropped below the preestablished cutoff of 50 employees. The 101 firms in the final sample represented 72 different 4-digit Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) codes. No dominant industry classification emerged; each 4-digit SIC code was represented by 6 or fewer firms. The average sales revenue was $134 million (SD = $440 million), and the average firm age was 48.63 years (SD = 31.12 years). A total of 63 firms were privately held, and the remaining 38 were publicly owned. The firms in this sample employed an average of 805.60 people (SD = 2469.91).

A series of t-tests indicated that there was no difference (p > .10) between firms from which a response was obtained and nonresponding firms regarding their average age and size (the latter being represented by number of employees and annual sales revenue). When available, data for nonresponding firms were collected from secondary sources, including the Ward's Business Directory of U.S. Private and Public Companies. No significant differences (p > .10) in firm age or size (number of employees and annual sales revenue), or in any of the key research variables in this study, were found using t-tests that compared early- vs. late-responding firms. A firm was labeled an early responder if the survey was submitted in response to the initial solicitation. Meanwhile, a firm was classified as a late responder if the survey was submitted after a reminder was sent.

MeasuresThe following paragraphs describe the measures employed in this research. Table 1 shows the summary statistics and correlation matrix. The alpha coefficients all exceed the 0.70 value recommended by Nunnally and Bernstein (1994). The specific items comprising the scales for the independent variables are shown in the Appendix.

Summary statistics and correlation matrix.

| Variablea | Mean | s.d. | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sales Growth Rateb | −0.75 | 14.88 | n.a. | |||||||||||

| 2. Strategic Learning | 4.71 | .97 | .86 | 0.10 | ||||||||||

| 3. Strategic Decision-Making Style | 4.74 | 1.35 | .89 | 0.18† | 0.21* | |||||||||

| 4. Environmental Dynamism | 3.75 | 1.20 | .72 | 0.13 | −0.06 | 0.05 | ||||||||

| 5. Firm Age (years) | 48.63 | 31.12 | n.a. | −0.04 | −0.15 | 0.21* | −0.10 | |||||||

| 6. Firm Size (employees) | 805.60 | 2469.91 | n.a. | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.24* | ||||||

| 7. Entrepreneurial Orientation | 4.05 | 1.04 | .85 | 0.26* | 0.28** | 0.32** | 0.18† | 0.02 | 0.13 | |||||

| 8. Market Pioneering Orientation | 3.59 | 1.33 | .80 | 0.16 | 0.22* | 0.30** | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.11 | .52*** | ||||

| 9. Market Pioneering Orientation Squared | 1.75 | 2.13 | n.a. | −0.16 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.06 | .04 | 0.16 | |||

| 10. Structural Organicity | 4.97 | 1.28 | .89 | 0.15 | 0.31** | 0.29** | −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.05 | .25* | 0.17† | 0.06 | ||

| 11. Market Responsiveness | 4.92 | 1.33 | .87 | 0.32** | 0.30** | 0.32** | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.09 | .26** | 0.33** | 0.02 | 0.15 | |

| 12. Strategy Formation Mode | 4.12 | 1.32 | .90 | 0.05 | 0.25* | .43*** | 0.17† | 0.17† | 0.16 | .41*** | 0.13 | −0.12 | −0.01 | 0.18† |

N = 101.

The firm's sales growth rate, relative to its industry's average, served as the measure of that firm's performance. Firm sales growth rate was operationalized as the average growth rate in sales revenue over the latest 3-year period. When available, sales revenue values were obtained from secondary sources, and in all cases, these values were found to be equivalent to or rounded approximations of the values reported by primary sources. The 3-year average growth rate of each principal industry was calculated based on the Annual Survey of Manufacturers distributed by the U.S. Department of Commerce. To control for the differing growth rates of the industries represented in this study, the appropriate industry-specific value was subtracted from the 3-year average growth rate of the firm when computing the dependent variable. Sales growth rate was adopted as the dependent variable, because firm growth was often viewed as evidence that firms were proficient at adapting to the exigencies of their environments (e.g., Kuwada, 1998; Phelps et al., 2007).

Independent variablesStrategic learning self-efficacy was measured using the six-item, seven-point scale developed by Garrett et al. (2009). Higher scores indicated greater confidence in one's ability to learn from the outcomes of past strategic decisions and apply that knowledge when making new strategic choices. Covin et al.’s (2006) five-item, seven-point scale was used to measure the construct of strategic decision-making style. A higher score on this scale indicated a participative decision-making style, whereas a lower score indicated a more autocratic style. The construct of environmental dynamism was measured using a slightly modified version (altered response format) of Miller and Friesen's (1982) four-item scale. Higher scores reflected more dynamic environments; lower scores reflected more stable environments.

To determine the structure of the data used to construct the multi-item scales, the 15 items of the aforementioned measures were factor analyzed using principal components analysis and a Varimax rotation. Results indicated that the 15 items loaded (using a loading criterion of 0.50) on 3 separate factors corresponding to the theoretical structure of the scales. Moreover, no items loaded on more than one factor, and in all cases, the items that loaded on a factor did so at a magnitude of at least twice that of the nonloading items. In short, the factor analysis suggested a very clean factor structure for the independent variable scales.

Control variablesSeven variables were treated as controls in the current study: firm size, firm age, entrepreneurial orientation, market pioneering orientation, structural organicity, market responsiveness, and strategy formation mode. The measure of firm size used in this study was the firm's number of employees, as reported by the respondents. Firm age was assessed as the number of years the firm had been in business, as reported by the respondents. As there was some skewness in the size and age data, the natural logs of these variables were used in the analyses.

Entrepreneurial orientation and market pioneering orientation were controlled in the current study, because prior research (Covin et al., 2006; Mueller et al., 2012) suggests that strategic learning capability moderates the relationships these variables have with firm growth. Entrepreneurial orientation was measured with the nine-item, seven-point scale employed by Covin and Slevin (1989). Market pioneering orientation was measured using Covin et al.,’ (2000) four-item, seven-point scale. Notably, market pioneering orientation has been found to have an inverted u-shaped relationship with firm sales growth (Mueller et al., 2012). As such, to capture curvilinear effects on firm growth, a squared term was computed from the market pioneering data and used as an additional control variable.

Anderson et al. (2009) state that structural organicity, market responsiveness, and strategy formation mode fully mediate the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and strategic learning capability. The scales for structural organicity and market responsiveness were drawn from the work of Anderson et al. (2009). Structural organicity was operationalized with a four-item, seven-point scale on which firms with a more organic structure received a higher score than those with a more mechanistic structure. Consistent with Anderson et al. (2009, p. 227), market responsiveness was defined as “an organizational competency that enables a firm to react quickly to changing environmental stimuli” and was captured with a two-item, seven-point scale. Slevin and Covin (1997) developed the five-item, seven-point scale used to measure strategy formation mode. Higher scores represented a planned strategy formation mode, while lower scores represented an emergent strategy formation mode.

Analytical techniquesThe hypotheses were tested following the moderated regression analysis technique recommended by Arnold (1982). Hierarchical moderated regression analysis was chosen to analyze the data, because this technique enables the researcher to examine how theoretically defined moderator variables—in this case, strategic decision-making style and environmental dynamism—influence the relationship between two focal variables—in this case, strategic learning self-efficacy and firm sales growth rate—while controlling for the effects of other relevant factors. (These are factors entered into prior models that do not include the interaction terms, as noted by Cohen et al., 2013). In all models, the control variables were entered prior to the other independent variables to partial out their effects from the hypothesized relationships. Consistent with the method suggested by Allison (1977), when testing Hypothesis 4, all possible 2-way interaction terms were entered into the regression equation before the 3-way interaction term. Variance inflation factors computed for the independent variables were all well within the acceptable range (i.e., < 10) proposed by Hair et al. (1998). Thus, multicollinearity within the data did not appear to be a problem. Nonetheless, to minimize correlations between the independent variables and their interaction terms, the independent variables were centered in the manner suggested by Aiken and West (1991) prior to computation of the interaction terms.

ResultsTable 2 presents the results of the moderated regression analysis. Model 1 includes only the control variables. Market responsiveness is positively associated with firm sales growth rate (β = 0.27; p < .01), and market pioneering orientation has an inverted u-shaped relationship with firm sales growth rate (β = −0.24; p < .05). Firm age and size are not significantly associated with growth. Model 2 adds the strategic learning self-efficacy variable and the main effects of the moderators—strategic decision-making style and environmental dynamism. Strategic learning self-efficacy is not a significant (p > .10) predictor of sales growth rate when examined independently or in the presence of the 2 moderators, consistent with (null) Hypothesis 1. That is, firms with higher strategic learning self-efficacy scores are observed to grow no more quickly than firms with lower strategic learning self-efficacy scores.

Regression analysis results.a

| Dependent Variable:Sales Growth Rateb | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Variables | ||||

| Log Firm Age (years) | −0.059 | −0.055 | −0.021 | −0.043 |

| Log Firm Size (employees) | −0.068 | −0.080 | −0.079 | −0.111 |

| Entrepreneurial Orientation | .229† | .216† | .263* | .259* |

| Market Pioneering Orientation | .009 | .001 | .009 | .014 |

| Market Pioneering Orientation Squared | −0.204* | −0.210* | −0.148 | −0.125 |

| Structural Organicity | .060 | .053 | −0.025 | −0.050 |

| Market Responsiveness | .271&#¿;&#¿; | .257* | .138 | .107 |

| Strategy Formation Mode | −0.090 | −0.130 | −0.124 | −0.117 |

| Independent Variables | ||||

| Strategic Learning (SL) | −0.016 | −0.086 | −0.096 | |

| Strategic Decision-Making Style (SDMS) | .085 | .090 | .125 | |

| Environmental Dynamism (ED) | .110 | .119 | .037 | |

| 2-Way Interaction Terms | ||||

| SL x SDMS | −0.255* | −0.227* | ||

| SL x ED | −0.235* | −0.094 | ||

| SDMS x ED | −0.050 | −0.050 | ||

| 3-Way Interaction Terms | ||||

| SL x SDMS x ED | .286* | |||

| Model R2 | .188 | .204 | .318 | .365 |

| &#¿; R2 | .016 | .114 | .047 | |

| Model F | 2.661* | 2.077* | 2.860&#¿;&#¿; | 3.260&#¿;&#¿;&#¿; |

N = 101.

Model 3 includes the 2-way interaction terms used to test Hypotheses 2 and 3. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, Model 3 reveals that the interaction of strategic learning self-efficacy and strategic decision-making style is a significant (p < .05) predictor of sales growth rate. Moreover, the negative beta for the interaction term implies that strategic learning self-efficacy is most positively related to sales growth rate in the presence of a more autocratic (vs. participative) strategic decision-making style. Hypothesis 3 is also supported. Specifically, the negative and significant (p < .05) beta of the strategic learning self-efficacy times environmental dynamism interaction term implies that strategic learning self-efficacy has a more positive effect on sales growth rate among firms operating in more stable (vs. dynamic) environments.

Model 4 presents the complete regression equation in which the 3-way interaction effect of strategic learning self-efficacy, strategic decision-making style, and environmental dynamism on sales growth rate is tested. The beta for the 3-way interaction term is positive and significant (p < .01), which supports Hypothesis 4. This result indicates that when the strategic decision-making style is participative, strategic learning self-efficacy has a more positive relationship with sales growth rate among firms operating in more dynamic (vs. stable) environments. On the other hand, when the strategic decision-making style is autocratic, strategic learning self-efficacy has a more positive relationship with sales growth rate among firms operating in more stable (vs. dynamic) environments.

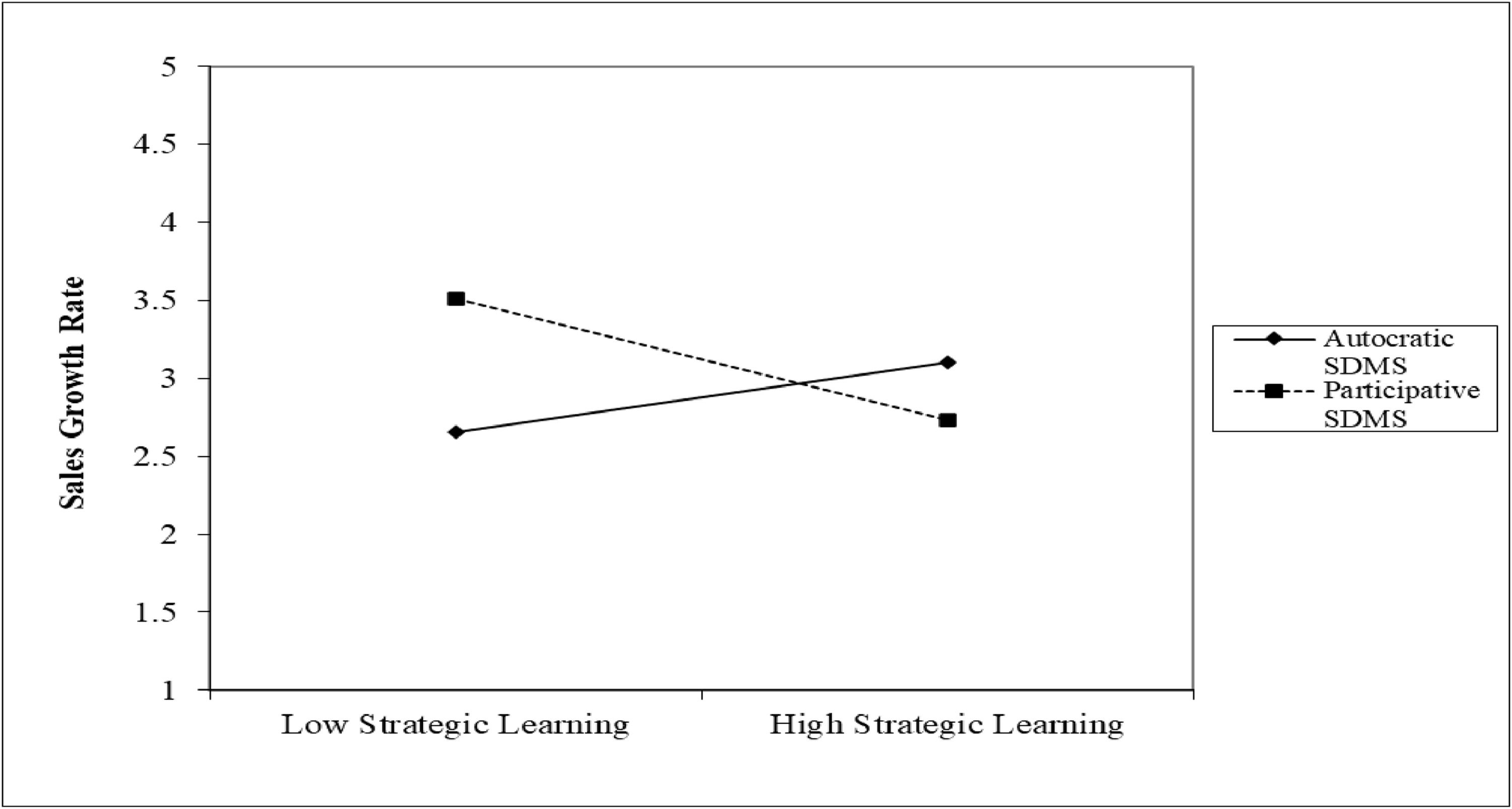

To graphically depict the identified moderator relationships, the interaction effects were plotted, as shown in Figs. 2–4. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, Fig. 2 shows that strategic learning self-efficacy has a positive effect on sales growth rate in the presence of an autocratic strategic decision-making style, and it has a negative effect on sales growth rate in the presence of a participative strategic decision-making style. Consistent with Hypothesis 3, Fig. 3 reveals that strategic learning self-efficacy has a positive effect on sales growth rate among firms operating in stable environments, and it has a negative effect on sales growth rate among firms operating in dynamic environments. Notably, the absence of a main effect of strategic learning self-efficacy on sales growth rate is readily inferable from either Figs. 2 or 3, because in both figures, averaging the slopes of the two lines would create a nearly flat line (and this would imply the absence of a strong relationship between strategic learning self-efficacy and sales growth rate).

The plot of the 3-way interaction effect is shown in Fig. 4. Consistent with the “a” portion of Hypothesis 4, under participative management, strategic learning self-efficacy has a more positive relationship with sales growth rate among firms operating in more dynamic (vs. stable) environments. The downward-sloping lines of both high and low dynamism imply that a negative overall relationship exists between strategic learning self-efficacy and sales growth rate under participative management. Nonetheless, the high dynamism line is less negative—or, equivalently in a statistical sense, more positive. Consistent with the “b” portion of Hypothesis 4, under autocratic management, strategic learning self-efficacy has a more positive relationship with sales growth rate among firms operating in more stable (vs. dynamic) environments.

Discussion and conclusionTheoretical implicationsThe current research has three principal theoretical implications. First and foremost, the findings suggest that strategic learning self-efficacy as defined and operationalized herein may not be strongly and inherently tied to efficacious organizational outcomes—firm sales growth rate, in particular. While the concept of strategic learning is depicted with a positive bias in the organizational learning literature (e.g., DiBella, 2001; Farooq & Vij, 2020; Thomas et al., 2001), results of this study suggest that the linkage between strategic learning self-efficacy and sales growth rate is quite modest (zero-order correlation of r = 0.10). Adopting a more neutral perspective on strategic learning is theoretically warranted based on the reality that strategic learning entails the enactment of changes in firm strategy, and significant strategic change typically occurs only after major performance shortfalls have been realized (Ketchen & Palmer, 1999; Miller, 1994). Thus, firms that exhibit strategic learning will typically be striving to reverse their fortunes. Significantly, their abilities to do this will be directly dependent on the extent to which their inferences about past strategic action–outcome relationships are accurate and remain valid in the current decision context. In short, theorists will be well served by heeding the advice of Huber (1991) and others (e.g., Crossan & Berdrow, 2003) that learning should be conceptualized in a value-neutral fashion.

Second, and related to the preceding point, organizational knowledge management processes have often been argued to drive firm performance (e.g., Hansen et al., 1999; Liang & Frösén, 2020; Zack, 1999). Nonetheless, the value of strategic learning as a process must be recognized as tied most directly to the content of strategic changes that reflect knowledge acquisition—that is, strategic learning is principally valuable to the extent that it leads to decisions and actions serving the interests of the firm. As suggested in Leavy's (1998) review of the concept of learning in the strategy field, too often the value of strategic learning as a process has not been conceptually distinguished from the value of the knowledge that accrues through the process. However, the exhibition of strategic learning processes per se cannot ensure that the resulting decisions and actions will lead to desired organizational outcomes.

Third, results of the current research imply that any reasonably complete model of strategic learning effectiveness should recognize the potential relevance and impact of both organizational and environmental conditions on learning outcomes (e.g., Baker et al., 2022; Wales et al., 2021). Prior discussions of strategic learning have tended to emphasize the roles of the organizational context (e.g., Baker & Sinkula, 1999; Wolff & Pett, 2007) or the firm's environmental context (e.g., Lant & Mezias, 1990) on learning outcomes. However, the possibility that organizational and environmental conditions may interactively influence learning outcomes has been largely overlooked. As such, existing theory tends to advance oversimplified models of the strategic learning process. Consistent with the tenet of situated learning theory that context affects learning outcomes (Brown & Duguid, 1991; Lave & Wenger, 1991), more fully specified strategic learning models that explicitly recognize the influence of interacting contextual conditions on learning outcomes are clearly warranted.

Managerial implicationsFour primary managerial implications can be inferred from the current study's results. First, the inclusion of multiple individuals in the strategic decision-making process via participative management should not be regarded as the normative approach to achieving effective strategic learning. While the current data reveal a positive relationship between strategic learning self-efficacy and (participative) strategic decision-making style (r = 0.21), participativeness was found to have a negative moderating effect on the strategic learning self-efficacy-firm sales growth rate relationship. This result implies that (when environmental dynamism's effects are controlled), autocratic management rather than participative management strengthens the relationship between strategic learning self-efficacy and firm sales growth rate (see Fig. 1). Thus, while strategic decision-making participativeness may facilitate the exhibition of strategic learning, it can also inhibit its effectiveness. This situation may exist because, as discussed by Covin et al. (2006), Wielemaker et al. (2000), participative management can lead to the removal of high risk–high return options from decision consideration; in this case, learning-derived strategy changes may be more modest or incremental in scope. When enacted strategic changes are more conservative in character, resulting firm performance effects will be predictably weaker.

Second, results of the current research suggest that when firms operate in dynamic environments, their interests may be well served if decision-makers prioritize a learning-by-analysis approach over a learning-by-doing approach to strategic learning. A learning-by-analysis approach is one in which decision-makers would strive to reduce the unpredictability of dynamic environments through data collection and analysis of those environments prior to taking any strategic actions within them. By contrast, a learning-by-doing approach is one in which decision-makers would strive to acquire relevant knowledge pertaining to their firm's operating environments by actively navigating within them. In short, the learning-by-analysis and learning-by-doing approaches represent two distinct knowledge acquisition strategies. As argued by Sorenson (2003), the benefits of learning-by-doing are reduced under conditions of environmental volatility. The rationale for this conclusion was stated as follows (Sorenson, 2003, p. 449): Most research relating learning to performance assumes a static environment; the same inputs yield success from one period to the next. In these stable environments, firms that can effectively adapt perform increasingly well over time, but consider the opposite extreme: A maximally volatile environment corresponds to assigning random numbers to map actions to performance. Because the factors of success in one period bear no relation to those in the next, any identification and selection of effective routines only results in superstitious learning (Lave & March 1975); by the time the firm acquires knowledge it no longer applies.

Related to the preceding implication, this research also suggests that developing a capability to foreshadow environmental events may be key to appropriating value from strategic learning. Foreshadowing as a means to reduce the uncertainty associated with dynamic environments (Buehring & Bishop, 2020; Haarhaus & Liening, 2020) is enabled through future-oriented decision-making tools commonly discussed as “strategic foresight” methods (e.g., Rohrbeck & Schwartz, 2013). These methods include, for example, scenario planning, technology roadmapping, and the Delphi technique (Vecchiato, 2012). While a full explanation of such methods is beyond the scope of this article, the key benefit to managers is the replacement of knowledge voids or implicit assumptions with conscious awareness of possible or probable future circumstances that have information value relevant to strategic decision-making.

The final principal managerial implication of this research is that senior executives should exhibit greater receptivity to the input of others as bases for strategic decision-making when environmental dynamism increases. This implication suggests that participative management can serve the purposes of a learning by-analysis strategy under conditions of environmental dynamism. More specifically, the inclusion of multiple individuals in the strategic decision process can increase the predictability of the environment through the provision of more potentially relevant and valid data points. When dynamic environments are better understood prior to strategic action being taken within them, the learning reflected though strategic actions will exhibit greater veracity. In short, strategic decision-makers should know when to open the decision process to input from others via participative management. Consistent with the findings of decision-making research conducted at lower levels of the organization (e.g., Scott-Ladd & Marshall, 2004), the current results suggest that participative management can help strategic decision-makers minimize the adverse effects of decision context ambiguity and unpredictability on decision quality, thus strengthening the learning–performance relationship.

Limitations and future research directionsBuilding from the current results and the limitations of this study, three directions for future research are proposed. First, additional research is warranted on the topic of how firms strategically learn—and, in particular, on the effects of a firm's learning strategy (or learning mode) on the strategic learning-firm performance relationship. There is no shortage within the literature of ways in which learning strategy can be characterized. Examples include exploratory learning vs. exploitative learning (March 1991), single-loop vs. double-loop learning (Argyris, 1992), acquisitive vs. experimental learning (Zahra et al., 1999), and informational vs. interactive learning (Gnyawali & Stewart, 2003). The precise knowledge acquired through distinct learning strategies can be quite varied. As such, how firms learn may impact the outcomes associated with the exhibition of a strategic learning capability. Consistent with the premise that learning strategy can drive learning outcomes, Gnyawali and Stewart (2003, p. 72) proposed, for example, that “as perceptions of uncertainty about the environment increase, organizations should increase their emphasis on the informational mode of learning.” By focusing on the relevance of learning strategy to the strategic learning-firm performance relationship, researchers may uncover insights on how learning effectiveness can be robustly facilitated across diverse organizational and environmental contexts. Relatedly, research has shown that individuals’ learning styles are associated with certain personality attributes—with more entrepreneurial individuals, for example, sometimes being shown to prefer active experimentation over reflective observation (e.g., Gemmell, 2017). Accordingly, future research might assess individual-level entrepreneurial orientation (see Clark et al., 2024) as a possible driver of strategic learning.

A second matter proposed for future research is the exhibition of strategic learning when success rather than failure is the impetus for strategic change. Prior evidence suggests that firms are more apt to learn from and change their strategies in response to their failures than in response to their successes (e.g., Ketchen & Palmer, 1999; Maidique & Zirger, 1985). Likewise, the recognition of threat has been shown to be a more powerful driver of strategic change than the recognition of opportunity (e.g., Kotter, 1995; Miller, 1994). In general, the literature on strategic learning has been largely limited to theory and research pertaining to underperforming firms. Nonetheless, firms can, and do, learn from their strategic successes (Baumard & Starbuck, 2005; Lant & Montgomery, 1987). Research is needed that models and tests how the learning-from-success process differs from the learning-from-failure process, as well as the conditions under which each of these processes promote firm performance.

Finally, management practices such as participatory leadership and democratic decision- making have been shown to vary greatly across countries and cultural contexts (Huang et al., 2011; Pavett & Morris, 1995), with receptivity to and the efficacy of participative management being very culture specific. As such, the current study's findings might not be replicable in contexts outside the United States, where participative management is looked upon less favorably (Jago, 2017). One might expect, for example, that a participative strategic decision-making style will be associated with lower levels of strategic learning self-efficacy in cultural contexts where participative management is not particularly valued, with the strength of this relationship possibly predicting subsequent firm performance.

Firms whose strategic managers are reporting high proficiency at strategic learning—as indicated by high strategic learning self-efficacy scores—may generally be no better or worse performing than firms whose managers make no such claims. Nonetheless, strategic learning self-efficacy is associated with firm performance under particular decision-making conditions and in particular environmental contexts. As such, the evaluative context in which strategic learning self-efficacy is reported appears to determine whether the indicated learning is, in fact, efficacious as a driver of firm growth.

CRediT authorship contribution statementJeffrey G. Covin: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Alessandra Lisanti: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Giovanni Latorre: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Katrina M. Brownell: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Patrick M. Kreiser: Writing – review & editing.

Respondents were asked to respond to the following statements on a 7-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (= 1) to “strongly agree” (= 7).

The strategic learning self-efficacy scale

- •

My business is good at identifying strategies that haven't worked.

- •

My business unit is good at pinpointing why failed strategies haven't worked.

- •

My business unit is good at learning from its strategic/competitive mistakes.

- •

My business unit regularly modifies its choice of business practices and competitive tactics as we see what works and what doesn't.

- •

My business unit is good at changing its business strategy midstream as we get a sense of the likely effectiveness of our actions.

- •

We are good at recognizing alternative approaches to achieving our business unit's objectives when it becomes clear that the initial approach won't work.

The strategic decision-making style scale

- •

Our major operating and strategic decisions result from consensus-oriented decision making.

- •

Our major operating and strategic decisions are made by single individuals with responsibility in the decision area. (reverse coded)

- •

Our business unit's philosophy is to involve all levels of management in major operating and strategic decisions.

- •

Consensus seeking is a common and pervasive decision-making practice in my business unit.

- •

Information and power are shared extensively in making decisions in my business unit.

The environmental dynamism scale*

- •

Actions of competitors are generally quite easy to predict.

- •

The set of competitors in my industry has remained relatively constant over the last 3 years.

- •

Product demand is easy to forecast.

- •

Customer requirements / preferences are easy to forecast.

*All items were reverse-coded.