The purpose of this study was to investigate the mechanisms through which intimate relationships influence the business achievements of both men and women. The study involved 400 Small and Medium Enterprises (SME) entrepreneurs (177 women and 223 men) in Poland, all of whom are currently in a relationship and have been running their businesses for at least three years. We used seven tools in the study: the Entrepreneurial Success Scale, the Marital Communication Questionnaire, the KDM-2 Matched Marriage Questionnaire, the Relationship Support in Business Scale, the Achievement Motivation Inventory, the GSES Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale, and a personal data sheet. The findings confirmed the role of romantic partners in enhancing psychological traits, such as self-efficacy and achievement motivation, which are critical for business performance. This effect was particularly pronounced among female entrepreneurs. Satisfying intimate relationships and supportive communication (especially with regard to entrepreneurial activity) can contribute to the better business performance of individuals.

An analysis of the family environment highlights the crucial role of the family in fostering the development of entrepreneurial skills and attitudes. Early research in this area focused primarily on examining “family businesses,” where entrepreneurial traditions that were passed down through generations provided a strong foundation for sustained company growth. Subsequent research on the familial determinants of entrepreneurial success shifted attention to the psychological resources that are essential for effective management and that are cultivated within the family environment. This shift emphasized the important fact that entrepreneurial success, while largely “objectified” (with the economic factor being one of its primary determinants), also encompasses a subjective dimension. This subjective aspect relates to the broader concept of “self-realization,” including personal satisfaction, work–life balance, and work–family balance, among other factors (Kirkwood, 2016). This assumption enables us to move beyond the analysis of factors that promote risk-taking or competitive tendencies, shifting the focus to less “fierce” variables such as self-efficacy, self-esteem, and a sense of coherence.

Each of the abovementioned senses clearly has its roots “somewhere” deep within. In psychology, this depth always refers to the family of origin. However, this analysis is not a straightforward examination of the relationship between two variables; rather, it provides a way to pinpoint mechanisms and explore the subtle differences in the pathways of family interactions. Gradually learning these “subtleties” brings us closer to a deeper understanding of how the family environment can either foster or hinder an individual's entrepreneurial growth.

In fact, the abovementioned family-focused entrepreneurial success research is embedded in the present work. However, the discussion extends beyond the context of the family of origin, focusing instead on the resources embedded within an individual's own family environment, particularly intimate, romantic relationships/partnerships. This project contributes to the ongoing scholarly debate on the role of family in entrepreneurial effectiveness by introducing a new dimension—an in-depth analysis of how intimate relationship communication and relationship satisfaction influence the psychological factors that foster or hinder entrepreneurial success. Thus, the main objective of this study is to verify a model in which the quality of the romantic relationship and communication processes translates into entrepreneurial effectiveness while also affecting self-efficacy and achievement motivation. Therefore, the overarching goal is to simultaneously examine the significance of various dimensions of dyadic functioning for entrepreneurial effectiveness. Previous studies have largely concentrated on a single link (usually emotional support) in the context of partners’ business activities. Such an approach is highly reductionist and suited only to simplified theoretical models. In reality, everyday couple dynamics rarely reduce themselves to a single communicative dimension; rather, they comprise a set of messages (e.g., supportive and depreciating). Even in longstanding, successful relationships, deprecating messaging can occur. Consequently, theoretical models that incorporate intimate relationships as a determinant of entrepreneurial performance should account for multiple communication dimensions without marginalizing any one of them. Thus, the primary aim of this project is to conduct an in‑depth analysis of how different facets of communication (support, engagement, and deprecation) and partner functioning (intimacy, self‑fulfillment, similarity, and disappointment) influence entrepreneurial effectiveness.

Literature reviewIn their study of 253 small and medium-sized enterprises, Powell and Eddleston (2013) provided compelling evidence of the significance of family–work synergy. They demonstrated that enriching connections between the family and business environments can have a significant effect on an individual's entrepreneurial achievements. Other studies have likewise confirmed these relationships (Jabeen et al., 2015; Ungerer & Mienie, 2018). Van Auken and Werbel (2006) demonstrated that the survival of a company is partly contingent on spousal involvement, arguing that the decision to found a business should hinge not only on an analysis of opportunities but also on the extent to which a spouse shares a common vision regarding goals, risks, and the benefits derived from entrepreneurship.

Consequently, analyses of family dynamics for business performance provide robust evidence of the interdependence between these two dimensions (Gill & Kaur, 2015; Guedes et al., 2022). For instance, Dewitt et al. (2023) examined family and relational dynamics in the context of women’s entrepreneurship, a domain that continues to prevent many women from selecting entrepreneurship as a preferred career path. Their qualitative findings confirmed that marital, familial, and societal expectations, as well as gender stereotypes, negatively influence decision‑making processes and the entrepreneurial trajectory of female entrepreneurs. Their study also revealed that women who do not come from business families still face pressure from relatives to abandon an entrepreneurial pursuit because it remains perceived as risky. Interesting insights are also provided by Maharajh et al. (2024), who investigated how family dynamics affect firm performance, with effective leadership acting as a mediator and the generation and firm size serving as moderators. Their analysis revealed that the overall success of family businesses depends on leadership effectiveness; however, they reported no relationship between family‑firm success and the generation. Similarly, effective leadership did not significantly correlate with firm size, the generation or family dynamics. These results suggest that high-quality leadership is consistent across generations and across firms of varying scales.

Family dynamics, including communication patterns, modeling, conflict resolution, role distribution, and boundary setting, can also shape the psychological resources that are essential for effective entrepreneurship. This phenomenon applies to both family‑owned and nonfamily enterprises. Although research in this area remains sparse, a handful of studies have underscored the critical role of parents’ business‑related modeling processes in shaping their children’s entrepreneurial intentions and attitudes (Davidsson & Honig, 2003; Krumboltz et al., 1976; Schmitt-Rodermund, 2004; Scott & Twomey, 1988; Wang & Wong, 2004). Analysis of parental attitudes (demands, protectiveness, and consequences) as well as family communication processes (Staniewski & Awruk, 2021) has likewise confirmed the importance of a secure family environment, balanced demands, and an open, satisfying intrafamily dialogue (Kirkwood, 2016) for shaping entrepreneurial potential. The “trajectory” of parental interactions appears to depend on the psychological potential under analysis. Therefore, to fully understand the mechanism described, it is essential to trace the sequences in which different variables act as mediators of the relationship. Confirmation has been provided by results presenting empirical verification of the model, where self-esteem and achievement motivation were used as mediating variables (Staniewski et al., 2025). In this case, the role of parental attitudes of autonomy, specific communication and modeling was highlighted, confirming once again that the role of the family environment in achieving entrepreneurial success cannot be marginalized.

Conversely, family relationships can pose some of the greatest challenges and risks to a firm: internal conflicts and ineffective conflict‑management strategies, divergent viewpoints or the desire to subordinate corporate governance to personal interests (Adriansah & Mubarok, 2023), interpersonal dynamics among family members in a business, personal issues, an overly large number of family participants (exceeding ten) and ambiguous internal hierarchies. All the factors above can threaten a firm’s annual revenue and turnover (Kets de Vries, 1993; Farrington et al. 2010; Mihic et al., 2015; Rodriguez et al., 1999; Sorenson, 1999).

Theoretical background and hypothesesThe family factor can be considered more broadly, extending beyond the family of origin to encompass the nature of the intimate romantic relationship. By examining the analogy between family and work relationships, we can assume that the two areas (marriage/relationship and entrepreneurial effectiveness) are interconnected, making it difficult to fully separate them. As Edwards and Rothbard (2000) report, the areas of family and labor are linked by a number of mechanisms that include spillovers, compensation, resource drain, or congruence. As a result, it is difficult to speak of a complete separation of the professional and familial (private) planes. Considering the spillover mechanism, i.e., the process of interaction that leads to mutual similarity between areas (Lachowska, 2012), it can be assumed that the quality of the relationship/marriage is significantly linked to achievements at the business level. This assumption is also supported by results showing a significant role of the direct and indirect commitment of wives in the activity and business efficiency of their spouses (Danes et al., 2010; Rosenblatt et al., 1985). Other studies confirm these relationships. For example, Welsh and Kaciak (2019) reported that personal problems influence female entrepreneurs’ performance only when family commitments are affective rather than instrumental; a positive effect emerges solely for affective bonds, such as emotional support. On this basis, we propose the following:

H1 Entrepreneurial success depends on the quality of the intimate relationship, with the relationship between entrepreneurial success and intimate relationship quality being mediated by self-efficacy and achievement motivation.

The hypothesis of a mediating role of self-efficacy and achievement motivation is supported by several studies that have demonstrated their predictive value for business performance. Examples include the work of Hmieleski and Corbett (2008) and Cassar and Friedman (2009). These authors demonstrated that a sense of self-efficacy enhances the chances of business growth by increasing the likelihood of starting one's own business, the percentage of wealth invested in the venture, and the number of hours per week that an entrepreneur dedicates to it. Conclusions regarding the role of self-efficacy and achievement motivation in entrepreneurial performance have also been highlighted in several other studies (Drnovšek et al., 2010; Oyeku et al., 2014; Prihatsanti, 2018; Singh, 1978), which show that achievement motivation (especially in the elasticity and dominance dimensions), along with self-efficacy and self-esteem, are closely linked to an individual's entrepreneurial success (Staniewski & Awruk, 2019). Additionally, Laguna et al. (2017) reported that self-efficacy beliefs predict work engagement and enthusiasm, whereas work engagement predicts enthusiasm. Consequently, the results reveal that there are reciprocal relationships between self-efficacy, positive affect, and work engagement among entrepreneurs, revealing the dynamic interrelationships between personal resources and work engagement over time.

However, relationships cannot be considered in isolation from communication processes. Messages conveyed by partners may encompass a range of dimensions, including general expressions of interest in the partner, his or her needs, and his or her problems (support); fostering an atmosphere of understanding, closeness, affection, and admiration (commitment); or, conversely, manifesting aggression, controlling behavior, and disrespecting the partner's dignity (depreciation) (Plopa, 2008). Understood in this way, communication can be considered nonspecific, namely, something cannot be narrowed down to a specific subject area. In contrast, specific communication is geared toward supporting or even discouraging initiatives in a well-defined area of an individual's functioning. With respect to this research project, it refers to supporting, encouraging, and motivating individuals to undertake activities aimed at developing their business. Given the close links between intimate relationship satisfaction and communication processes (Haris & Kumar 2018; Litzinger & Gordon, 2005; Rehman & Holtzworth-Munroe, 2007; Tavakol et al., 2017), we propose the following:

H2 Entrepreneurial success depends on partner communication (nonspecific and specific), with the relationship being entrepreneurial success and partner communication being mediated by self-efficacy and achievement motivation.

This hypothesis is confirmed by Kurniawan and Sanjaya's (2016) study of 61 married entrepreneurs. They demonstrated the important role of intimate relationship communication for business performance, thus noting the positive relationship between communication (understood as conflict management and advice strategy) and entrepreneurial performance, with the mediators of the aforementioned relationship being spouse commitment and social support.

As the empirical evidence shows, partner communication is significantly related to relationship quality and satisfaction. This point has been demonstrated by studies conducted over the past several decades (Boland & Follingstad, 1987; Litzinger & Gordon, 2005; du Plooy & de Beer, 2018).

To capture the phenomenon of partnership as fully as possible, it cannot be examined in isolation from communication processes. Hence, we introduce the variable nonspecific communication into the model, which represents general support for the partner, involvement, appreciation, and so forth. In our model, however, we do not explain relationship satisfaction; instead, we focus on entrepreneurial success. Thus, the links between an intimate relationship (communication and relationship quality) and business effectiveness are not as obvious as one might assume. Accordingly, we seek to verify whether the seemingly intuitive relationship in which a strong relationship equates to greater entrepreneurial effectiveness actually holds true in practice. Paradoxically, let us not rule out that a failing relationship might actually spur higher performance: the drive to be recognized in another arena could motivate individuals to work harder, which may translate into better business results. Because the connections between the relationship (relationship quality, which is inseparably intertwined with relationship communication) and business outcomes are not straightforward, we consider it appropriate to include these variables in our model. Given that partnership is a highly complex phenomenon, we also add a business‑specific dimension of communication to the model—specific communication. By doing so, we aim to differentiate the roles of nonspecific versus specific communication in influencing entrepreneurial effectiveness. Thus, we seek to determine whether, in relation solely to business achievements, warm conditions are required—namely, a successful partnership that offers both general (nonbusiness) and specific (strictly business) support, appreciation, and involvement—or whether merely recognizing the partner within the entrepreneurial context suffices. In the latter scenario, a failed partnership could trigger a desire to compensate for dissatisfaction in one domain by achieving success in another; partner messages that specifically acknowledge accomplishments would further reinforce this mechanism. Analyzing these subtle distinctions requires simultaneously juxtaposing two dimensions—communication and relationship quality; doing so constitutes a novel contribution to the literature. It therefore appears that including only a single dimension of relationship functioning, whether nonspecific communication, specific communication, or relationship quality, would be overly reductionist. Consequently, we choose to incorporate all three into the model simultaneously.

Given that the literature emphasizes the role of messages focused on emotional support of the partner/spouse in terms of running one's own business, it is assumed that specific communication will have the greatest predictive value for the business achievements analyzed (Chaudhary & Srivastava; 2022; Saral et al., 2019; Vadnjal & Vadnjal, 2013). Thus, we propose the following:

H3 Among the variables analyzed, specific communication has the strongest relationship with entrepreneurial success.

Based on the research hypotheses formulated above, we develop a theoretical model of entrepreneurial success (Fig. 1).

Given the hypotheses proposed above, the main objective of this study is to attempt to empirically verify the theoretical model of entrepreneurial success.

MethodologyStudy procedureThe survey, conducted between 2023 and 2024, included a sample of 400 entrepreneurs from the SME sector operating across Poland. Two criteria were assumed for the inclusion of people in the study: (a) being self-employed for a minimum of three years and (b) being in a hetero- or homosexual relationship (marriage/cohabitation). The surveyed entrepreneurs were selected via random sampling from the Polish electronic register of entrepreneurs (CEIDG), and the survey itself was conducted by qualified interviewers. Statistical analyses were performed via SPSS 29 for Windows and AMOS 29.

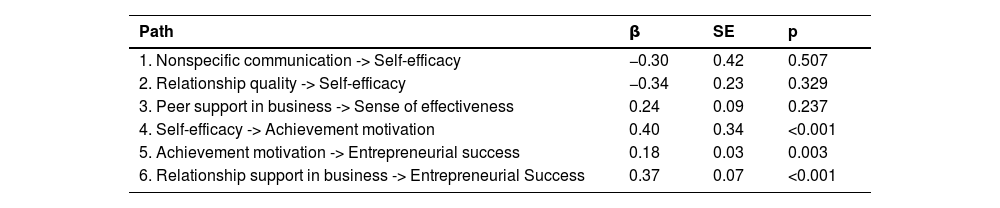

Study sampleThe sample consisted of 177 women (44.3 %) and 223 men (55.7 %), ranging in age from 23 to 77 years (M = 44.76; SD=9.01). A total of 400 SME entrepreneurs with their own businesses in Poland were surveyed. The largest percentage of respondents were those who started their businesses between 2010 and 2020 (N = 249; 62.25 %), and the smallest percentage were those who did so between 1970 and 1979 (N = 1; 0.25 %). The percentage distribution of respondents based on the period in which they started their own business is shown in Fig. 2.

Among the respondents, the highest number were those running a company in the Mazowieckie voivodeship (N = 198; 49.5 %), Dolnośląskie voivodeship (N = 28; 7 %) and Wielkopolskie voivodeship (N = 26; 6.5 %).

Most businesses were in the service sector (N = 283; 70.8 %) with local coverage (N = 212; 53 %). The respondents cited their own funds (N = 383; 95.8 %), credit (N = 70; 17.5 %), and alternative sources of funding (N = 54; 13.5 %) as the main sources of business financing. Fewer respondents used funds from the European Union (N = 49; 12.3 %), grants from the state budget (N = 44; 11 %), and loans (N = 22; 5.5 %). Table 1 shows details regarding the respondents’ companies.

Sample and Company Data.

Among the respondents, the highest number had a master's degree (N = 177; 44.3 %) and secondary technical education (N = 69; 17.3 %). All individuals were in a relationship—formal (N = 351; 87.8 %) and informal (N = 49; 12.3 %)—with an average span of 18.78 years (SD=9.62; min.= 1; max.=57 years). The largest percentage of the sample was composed of individuals with two children (N = 185; 46.3 %). Detailed sample data are provided in Table 2.

Sample Sociodemographic Data.

Seven questionnaires were used to operationalize the variables in the study: the Entrepreneurial Success Scale [Skala Sukcesu Przedsiębiorczego], the Marital Communication Questionnaire [Kwestionariusz Komunikacji Małżeńskiej], the KDM-2 Matched Marriage Questionnaire [Kwestionariusz Dobranego Małżeństwa KDM-2], the Relationship Support in Business Scale [Skala Wsparcia Partnerskiego w Biznesie], the Achievement Motivation Inventory, the GSES Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale, and a personal data sheet. The selection of the instruments above was driven primarily by their satisfying psychometric properties and their extensive use in psychology and management research. For example, the GSES is a widely adapted tool that has been used over the past three decades in numerous countries, and its psychometric characteristics have been repeatedly verified and confirmed (e.g., Pilafas et al., 2024; Das et al., 2024). The instrument’s reliability was tested across 23 countries, yielding correlation coefficients ranging from 0.76 to 0.90. Similarly, the Achievement Motivation Inventory (Byrne et al., 2004), renowned worldwide and repeatedly examined from a psychometric perspective, was adapted to the Polish context by Klinkosz and Sękowski (2006). The instrument’s psychometric parameters were evaluated on a sample of >1176 individuals. Reliability was assessed via internal consistency coefficients (α = 0.96) as well as test-retest methods. The next two instruments, the Marital Communication Questionnaire and the Matched Marriage Questionnaire, were employed to assess relational patterns. Their selection was largely driven by their high reliability and validity, as confirmed in a series of method studies conducted by the authors (Kaźmierczak & Plopa, 2008; Plopa, 2016). When researching Polish entrepreneurs, our priority was to use instruments that had been tailored or adapted to the relational dynamics characteristic of Polish marriages/partnerships. Both tools fit this criterion exceptionally well: in Polish studies focusing on relational aspects, they have been used repeatedly and are regarded as useful and reliable measures (Jankowska, 2016; Lipińska‑Grobelny, 2022; Wańczyk‑Welc & Marmola, 2017). The Entrepreneurial Success Scale is an author‑developed instrument, with its design and construction work commencing in 2019 (Staniewski & Awruk, 2019; Staniewski & Awruk, 2021). Since then, it has been employed several times in research, most recently in 2025 (Staniewski et al., 2025), leading to modifications and refinements relative to the original version. In pilot studies, the questionnaire’s internal consistency (α) was 0.92. Its theoretical validity was examined through a series of factor analyses. An exploratory analysis using Kayser’s scree‑plot method revealed a three‑factor structure for the instrument. The three‑factor solution was not confirmed in confirmatory factor analysis; consequently, a unidimensional structure was adopted for the scale. Work is currently underway to produce a comprehensive report on the instrument’s psychometric parameters. The Relationship Support in Business Scale is a new instrument developed specifically for this research project. Its construction was motivated by the lack of an existing measure that addresses the highly specific domain of providing support to a romantic partner strictly within the business context. Psychometric analyses led to revisions of the scale’s structure: the original 19-item version was shortened to 12 items, with items with low discriminatory power removed to preserve reliability. Exploratory factor analysis confirmed a single‑dimensional structure (Staniewski & Awruk, 2025). A detailed description of each instrument is presented below.

Entrepreneurial Success Scale [Skala Sukcesu Przedsiębiorczego (SSP)]—a tool used in this study to operationalize the entrepreneurial success variable. This is a 24-item tool developed by Staniewski, Awruk, and Leonardi (Staniewski et al. 2025). Items are used to assess the prosperity of the enterprise and the degree of satisfaction with its prosperity in various areas. The respondent's task is to answer individual questions by marking one of the response options. Some questions require only a yes/no answer. For other questions, the response options are yes/no/don’t know. In this questionnaire, it is possible to calculate an overall score by adding up the scores from all the questions. This score is an overall indicator of entrepreneurial success. The reliability of the scale in this study, which was calculated via Cronbach's alpha method, was α= 0.89. Sample questions include the following: Are you satisfied with how your company is developing? Does operating your own business give you a higher social status? Do you feel that you have been successful in running your business?

Marital Communication Questionnaire [Kwestionariusz Komunikacji Małżeńskiej (KKM)]—used in this study to operationalize the variable nonspecific intimate relationship communication. The KFM is a 30-item tool developed by Kaźmierczak and Plopa (2008). The tool measures intimate relationship communication, including its 3 dimensions:

1. Support—showing respect to the partner and taking an interest in him or her, his or her needs, and his or her problems. High scores on this subscale indicate that the respondent perceives his or her partner as supportive, respectful, and appreciative. According to the respondent, the partner shows interest in his or her problems or needs and actively engages in joint problem‑solving. The respondent believes that his or her partner cares for him or her not only during difficult moments but also throughout various everyday situations.

2. Commitment—building an environment of understanding and closeness, showing affection, arranging shared activities, and praising. A high score indicates that the respondent believes that his or her partner can create an atmosphere of mutual understanding and closeness in the relationship. The partner achieves this by expressing affection, emphasizing the respondent’s uniqueness and importance, adding variety to everyday routines, and preventing conflicts within the partnership.

3. Deprecation—exhibiting aggression toward the partner, controlling his or her actions, and disrespecting his or her integrity. A high score indicates a strong tendency for the respondent’s partner to devalue him or her. According to the respondent, the partner displays aggression toward him or her, lacks respect, is controlling, and enjoys dominating the relationship.

This questionnaire has 4 versions (wives’ assessment of their own behavior, wives’ assessment of husbands’ behavior, husbands’ assessment of their own behavior, and husbands’ assessment of wives’ behavior). This study used only those versions that assess the partner’s behavior. The respondents’ task is to respond to each statement by choosing one answer on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (I never act like this) to 5 (I always act like this). The reliability of the questionnaire in this study was satisfactory and was α=0.94 for the support dimension, α=0.88 for the commitment dimension, and α=0.92 for the depreciation dimension. Examples of test items include the following: My spouse/partner openly shares his or her feelings for me. My spouse/partner criticizes me. My spouse/partner insists on imposing his or her views upon me.

Matched Marriage Questionnaire [Kwestionariusz Dobranego Małżeństwa (KDM-2)]—a tool developed by Plopa and Rostowski (Plopa, 2016) that is used to assess relationship satisfaction. This questionnaire contains 32 items and is used to measure 4 dimensions of marital satisfaction:

- 1)

Intimacy—the level of satisfaction with being in an intimate relationship; satisfaction with building an open, intimate relationship. A high score indicates the level of intimacy of the partners and the conviction of their mutual love.

- 2)

Self-fulfillment—the degree to which spouses can fulfill various roles and become self-fulfilled. A high score indicates that for spouses, the relationship is one of the most important elements of a satisfying life.

- 3)

Similarity—the degree to which spouses agree on important marital and family goals, namely, leisure time, relationship development, family traditions, child rearing, and the organization of daily life.

- 4)

Disappointment—used to measure the degree of dissatisfaction with the marriage, the feeling of being limited in the relationship (frustration related to the need for autonomy), the degree of withdrawal by the partner, and thus the partner's failure to take responsibility for the relationship.

In addition to measuring the results in the four dimensions above, it is possible to calculate the overall level of marital satisfaction by summing the scores from all the items (with the reversal of the scores in the Disappointment subscale). The respondent's task is to respond to each question by choosing one of five options (on a 5-point Likert scale): strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, or strongly disagree. The reliability of the questionnaire in this study was α=0.91 for intimacy, α=0.89 for disappointment, α=0.84 for self-fulfillment, α= 0.84 for similarity, and α=0.96 for the overall score. Examples of test items include the following: My spouse/partner’s temperament aligns with my own. We try to spend our free time together. Over time, the bond between us deepens, and we feel more connected. I regret the loss of independence and freedom that characterized the premarital period.

The Relationship Support in Business Scale [Skala Wsparcia Partnerskiego w Biznesie (SWPwB)] is a 12-item tool designed to measure relationship-provided support in the context of entrepreneurship and was developed by Awruk and Staniewski. It assesses messages that convey faith in the intimate partner's entrepreneurial endeavors, provide emotional support, express appreciation, and offer assistance with the partner's business. The respondents are asked to rate each item using a scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). The final scores are calculated by summing the individual scores from all items. High scores indicate a high intensity of support received by the intimate partner. In this study, the tool had a satisfactory reliability parameter of 0.94. Examples of test items include the following: In the professional domain, I feel valued by my spouse/partner. My spouse/partner has always believed that I will achieve the career and business goals I set for myself. My spouse/partner assists me in running my company.

The Achievement Motivation Inventory(LMI) is a tool used to operationalize the achievement motivation variable for the purposes of the current project. The LMI is a tool developed by Schuler, Thornton, Frintrup, and Prochaska; the Polish version was developed by Klinkosz and Sękowski (2006). The tool includes two versions. The first (longer) is a 170-item tool with 17 subscales, representing different aspects of motivation: compensatory effort, competitiveness, confidence in success, dominance, eagerness to learn, engagement, fearlessness, flexibility, flow, goal setting, independence, internality, persistence, preference for difficult tasks, pride in productivity, self-control, and status orientation. However, this study uses the other, shortened, 30-item version of the tool. This shortened version allows for the calculation of a total score, which is an indicator of the level of achievement motivation of the respondent. The respondents rated each statement by selecting an option on a scale from 1 (does not apply at all) to 7 (applies fully to me). The reliability of the inventory in this study was satisfactory at α= 0.82. Sample questions include the following: When I accomplish something difficult, I am proud of myself. Faced with an important task, I prefer to prepare thoroughly rather than superficially. Earlier in life, I decided to make something of myself.

The Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES) is a short scale used to measure self-efficacy. The GSES is a 10-item tool developed by Schwarzer, Jerusalem, and Juczyński (Juczyński, 2012) that refers to Bandura's concept of self-efficacy, understood as the strength of an individual's general belief in the effectiveness of coping with difficult situations and obstacles. The respondent's task is to choose one answer out of four possible answers, ranging from no to yes. Scores are calculated by summing the scores from all the items. Scores range from 10 to 40. The higher the score is, the greater the sense of self-efficacy. The reliability of the questionnaire in this study was satisfactory at α= 0.85. Examples of test items include the following: I am consistently capable of solving difficult problems, provided that I exert sufficient effort. I am confident that I will effectively manage unexpected events. I can resolve most problems if I invest an appropriate amount of effort in them.

The personal data sheet is an original tool developed for the purposes of the current project, and it is used to measure sociodemographic variables such as age, gender, and education; data about the enterprise, such as the start date, the voivodeship where the company is run, the type of business, and sources of financing; and data about intimate relationships such as the duration of the relationship, the type of relationship (marriage or cohabitation), and children. Examples of test items include the following: What was the most recent annual turnover or total annual balance‑sheet sum of your business activities (in euros)? What is the current full employment level in your company, including yourself as owner? Indicate the predominant type of business activity.

ResultsWe began the statistical analyses by calculating descriptive statistics and testing for the normality of the distribution. Owing to the size of the sample, we decided to use the Kolmogorov‒Smirnov test for this purpose. The results obtained indicate a mostly left-skewed distribution (with a tendency to mark high scores) for the variables entrepreneurial success, achievement motivation, support, intimacy, similarity, self-fulfillment, relationship quality (KDM-2 overall score), and relationship support in business. The results are presented in Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics and Normality Test Results for the Subscales Used in the Study.

Verification of the theoretical model of entrepreneurial success commenced with the creation of a Spearman's rho correlation matrix. This was a preliminary step that preceded the decision to finalize the variables in the hypothesized theoretical model. Only the variables that significantly correlated with entrepreneurial success were the subject of further analysis. The results obtained are presented in Table 4.

Spearman's rho between the Analyzed Variables (N = 400).

The correlation matrix revealed a number of significant relationships between the analyzed variables, with the strongest being the relationship between entrepreneurial success and relationship support in business (moderate correlation). The results obtained confirmed the hypothesis of interrelationships among the analyzed variables, which allowed further analysis to be conducted to verify the hypothesized theoretical model.

To test this model, a series of SEM analyses was performed via the maximum likelihood method in AMOS 29 software. The models tested the effects of relationship support in business (specific communication) and nonspecific intimate relationship communication on self-efficacy, achievement motivation, and entrepreneurial success. Model verification analyses were conducted separately for Polish men and Polish women. The model for women is illustrated in Fig. 3, while Fig. 4 shows the model for men.

The models' goodness of fit to the data was evaluated via the goodness-of-fit Index (GFI), confirmatory fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and chi-square test (χ²/df). GFI values ≥ 0.90 and CFI values ≥ 0.95 are assumed to indicate a good and adequate fit of the model to the data (Hox & Bechger, 1998; Hu & Bentler, 1999). Values of χ2/df < 2 also suggest a good fit of the model to the data (Ullman, 2001). An RMSEA < 0.08 indicates a good fit to the data (Hox & Bechger, 1998).

The analysis revealed that the model for women had a good fit to the data. The chi2 value is nonsignificant (χ2(14) = 18,55; p = 0.183), indicating that there is no divergence between the observed covariance matrix and that implied by the model. In addition, χ2/df = 1.32, which confirms the absence of significant divergence.

The other indicators also show a satisfactory fit of the data to the model. The RMSEA index denoting the root mean square of the approximation error is 0.043, indicating a good model fit. The GFI (0.974) also indicates a good fit to the data, as does the comparative fit index (CFI = 0.995), which also shows a satisfactory value.

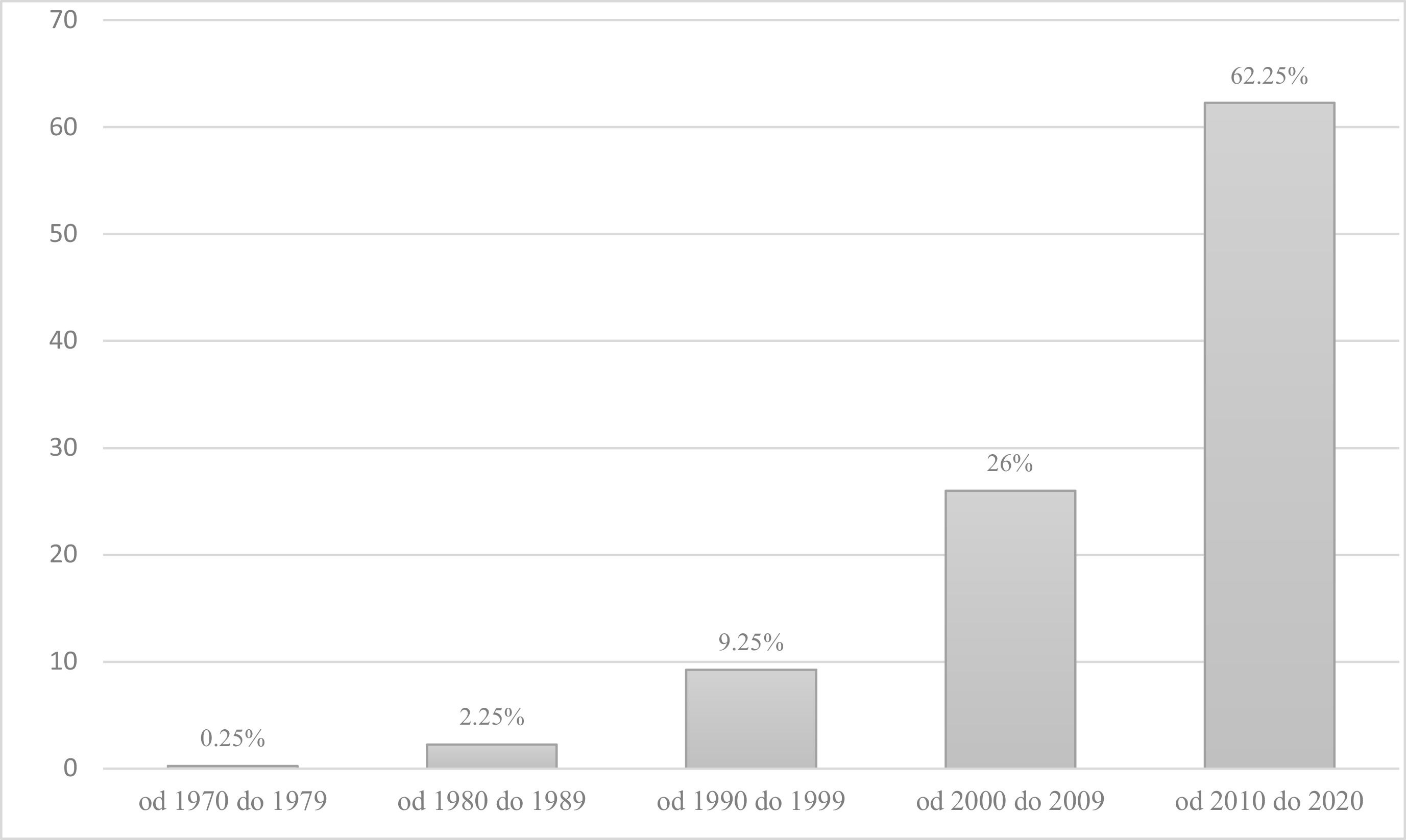

The model also tested the indirect effect of relationship support in business on success for the link between achievement motivation and success; bias-corrected 95 % confidence intervals based on bootstrapping (5000 samples) were used. The results of the analysis revealed no indirect effects. A statistically nonsignificant direct effect of achievement motivation on success was observed (beta = 0.12, p = 0.079), as well as a statistically nonsignificant indirect effect of achievement motivation on success mediated by the level of relationship support (beta = 0.01, p = 0.153). Table 5 presents standardized regression coefficients along with statistically significant values for the model applied to the Polish female sample.

Standardized Regression Coefficients for the Model Explaining Entrepreneurial Success among Polish Women.

An analogous model was then tested in the male sample. The model also showed a good fit to the data. The chi2 value is statistically significant, χ²(14) = 48.70, p < 0.001, indicating differences between the observed covariance matrix and that specified in the model. However, χ²/df = 2.44 suggests only a small difference. Other indicators also showed a good fit of the model to the data. The RMSEA is 0.080, the GFI = 0.954, and the CFI = 0.972 (Fig. 4).

The standardized regression coefficients, standard errors and statistical significance values are presented in Table 6.

Standardized Regression Coefficients for the Model Explaining Entrepreneurial Success among Men.

In compiling the results, models in which statistically nonsignificant paths were removed were also analyzed. Their removal from the models significantly worsened the fit parameters; therefore, we decided to retain them, preserving the models with the highest fit coefficients.

DiscussionTo date, analysis of the family environment in the context of entrepreneurial success has not been a primary focus of researchers. If anything, family has been considered in relation to the ways of communication and the functioning of family businesses (Adriansah & Mubarok, 2023; Kets de Vries, 1993; Rodriguez et al., 1999; Sorenson, 1999). There is a significantly smaller body of research analyzing this issue in nonfamily small businesses (Davidsson & Honig, 2003; Krumboltz et al., 1976; Schmitt-Rodermund, 2004; Scott & Twomey, 1988; Wang & Wong, 2004). Our study is unique in the sense that it seeks a mechanism for entrepreneurial success in the intimate relationships of entrepreneurs. On the one hand, this study represents a novel contribution, as there is limited research in this area to date; on the other hand, it is grounded in the numerous mechanisms that connect the domains of family and work (Edwards & Rothbard, 2000).

Our study focused on analyzing the complex mechanism through which intimate relationship interactions shape business performance. The results confirmed the proposed relationships between the variables, demonstrating that intimate relationships can play a crucial role in business success. Juxtaposing the results of the present study with those of previous studies (Staniewski et al., 2025) analyzing the importance of the family of origin (parental attitudes, family communication and modeling processes) for business achievement, it can be concluded that intimate relationships can influence entrepreneurial success to a greater extent than the family of origin can. Thus, this study confirms the conclusions that it is difficult to eliminate the spillover mechanism of different planes of human functioning (private and professional) (Edwards & Rothbard, 2000).

As in many previous studies (Cassar & Friedman, 2009; Drnovšek et al., 2010; Hmieleski & Corbett, 2008; Oyeku et al., 2014; Prihatsanti, 2018; Singh, 1978; Staniewski & Awruk, 2019), we also demonstrated the interrelationships between self-efficacy, achievement motivation, and entrepreneurial success. Therefore, this study once again proves that self-efficacy and achievement motivation are factors that are significantly related to business performance. However, the magnitude of their contribution to explaining entrepreneurial success requires further exploration to expand the range of psychological variables whose contribution to the development of business performance is similar to that generated by self-efficacy and achievement motivation.

The results of the present study also demonstrate gender differences in the models used to explain entrepreneurial success. Evidently, intimate relationships play a greater role in explaining women's business achievements than in explaining men's business achievements. For Polish women, both intimate relationship communication and the quality of the relationship appear to be important. Evidently, a satisfying intimate relationship based on closeness, mutual support, and commitment, in which both parties feel responsible for the relationship and, simultaneously, do not feel constrained by it, provides an important background for strengthening the qualities that are relevant to the actions taken to increase the chances of success in business. Among the variables analyzed, only specific communication (supportive messages aimed at the partner's business activities) appeared to be directly related to entrepreneurial success. Therefore, we can assume that its (specific communication) role is reduced to directly influencing business achievements or mediated by other psychological characteristics, which was not the subject of this analysis. Overall, the results obtained demonstrate the significant multifaceted participation of intimate relationships in effective female entrepreneurship. Considering the enduring social trend of gender stereotyping within entrepreneurship, it is logical that studies highlight the significant role of relational quality and partner communication among women. Despite profound societal change, women continue to confront social biases in terms of their professional roles (Dewitt et al., 2023; Gupta et al., 2009). Thus, a successful marriage or partnership can serve as a protective buffer that mitigates the stress imposed by societal expectations while simultaneously “fueling” continued effort in the face of such obstacles. This conclusion is reinforced by findings showing how central marital relationships are to women’s lives (Curran et al., 2010).

The results obtained in the Polish male sample only partially matched those obtained in the female sample. In this case, there were also (similar to women) significant correlations between relationship support in business and entrepreneurial success. Thus, appreciating a partner on a business level, cheering him or her on in his or her business endeavors, believing in the partner’s business activity, or directly helping him or her to run his or her business seem to have the greatest importance (among the variables analyzed) for men's entrepreneurial achievements. The opposite results were obtained for the other parameters of the intimate relationship. Neither relationship quality nor nonspecific partner communication was significantly associated with any of the psychological traits that were analyzed (i.e., self-efficacy or achievement motivation) and that are important for business performance. However, their removal from the model resulted in a deterioration of the model’s fit parameters, which nevertheless indicates some contribution to explaining entrepreneurial success. The analysis of the trend (direction of correlations) in this case is interesting in that the correlations obtained turned out to be negative. Therefore, it is possible that an unsuccessful marital/relationship situation triggers a compensatory mechanism in men, which contributes to them taking steps toward greater satisfaction in other extramarital areas. The findings can be interpreted by drawing on research concerning men’s need for social support, their perceived stress levels, and the coping strategies that they employ. Studies indicate that compared with women, men experience less stress, which is associated with a more positive cognitive appraisal of events; this, in turn, may translate into a reduced drive to seek social support (Felsten, 1998). Such an explanation would account for the lower level of importance placed on relationship quality and nonspecific communication for men’s business outcomes. Beyond the cognitive interpretation, it is important to note that, with regard to running a business, men remain socially more supported. Consequently, they experience less family–work role conflict than women do and are therefore exposed to lower levels of stress arising from juggling multiple social roles. Moreover, Polish men tend to employ task‑oriented rather than emotion‑focused coping strategies (Matud, 2004). This pattern may reflect a compensatory response to relational difficulties—offsetting personal problems with professional achievements.

Conversely, as the present study demonstrates, a certain degree of domain‑specific support (i.e., support directed exclusively at business matters) can be beneficial in the occupational arena. These results suggest that when complex phenomena such as partner support are analyzed, it is essential to differentiate among their various dimensions. In this respect, the results obtained are partly in line with those of Chaudhary and Srivastava (2022), who emphasized the importance of relationship support (advising, encouraging, and comforting) for the business achievements of the spouse. Vadnjal and Vadnjal (2013) and Saral et al. (2019) emphasized the role of emotional support and spousal assistance in strengthening the need to achieve and develop one's business. Kurniawan and Sanjaya (2016), however, demonstrated the important role of partner communication in business performance, highlighting the positive relationship between communication (understood as a conflict management and counseling strategy) and entrepreneurial performance, with the mediators of this relationship being spouse commitment and social support. Additionally, Welsh and Kaciak (2019) reported that the impact of personal problems on the performance of female entrepreneurs depends on the type of support that they receive from their families. In this regard, emotional support proved to be the most important factor.

The primary objective of this study was to construct and empirically validate a model of entrepreneurial success that captures partner‑based functioning as faithfully as possible. Accordingly, the partner relationship cannot be reduced solely to support, motivation, and appreciation of one’s spouse. Most prior work adopts this narrow view, which tends to portray partnership in an overly idealistic rather than realistic manner. In reality, every partnership comprises a configuration of messages with varying dynamics: positive and negative communications fluctuate over time. The findings reported in this study confirm the validity of adopting and extending such an approach, thus achieving the research’s stated goal of this research.

Theoretical contributions and practical implicationsThe present research has both theoretical and practical implications. The foremost implication—that which is most directly tied to the stated aim of this study—is the development of a comprehensive theoretical model that simultaneously incorporates multiple dimensions of partner functioning. By developing such a model, this study offers a more complete and, crucially, a more realistic representation of partnership dynamics. Although theoretical models (particularly those that attempt to “illustrate” complex psychological phenomena) necessarily simplify reality, it remains essential to extend them in ways that maximize fidelity to real‑world conditions while preserving empirical testability. In other words, the proposed theoretical model must strike a balance between complexity and simplicity: being sufficiently intricate to capture as much of the phenomenon’s reality as possible while remaining streamlined enough to preserve clarity. Our model appears to meet this criterion. Moreover, it seamlessly integrates findings from earlier studies with new contributions. First, in addition to partner‑communication processes, we incorporated overall relationship quality, measured via dimensions such as intimacy, similarity, self‑actualization, disappointment, and general satisfaction. Second, regarding partner support, the model distinguishes not only its general level but also a more specific component that addresses business‑related assistance provided to the spouse. The results, particularly for men, seem to validate the need to differentiate between general and domain‑specific support (e.g., business‑focused assistance). The study also offers evidence that various dimensions of partner functioning differently contribute to entrepreneurial effectiveness, with notable gender differences emerging in this regard.

From a practical standpoint, attention should be paid to the instruments employed. The newly developed Relationship Support in Business Scale, created specifically for this research, constitutes an innovative self‑report measure. Despite its concise structure (12 items), it enables a more precise assessment of the highly specific construct of business‑oriented partner support. The instrument offers a dual advantage: it economizes research time (being relatively brief) while enabling a more comprehensive assessment of support than a single, short item could provide (e.g., “Do you provide business‑related support to your partner?”). In this sense, the scale is suitable for future investigations. The same holds true for the Entrepreneurial Success Scale. Designed for earlier studies, the success scale allows researchers to view entrepreneurial outcomes from both an objective (questions concerning company financial matters) and a subjective (items probing satisfaction with business operations) standpoint. Consequently, it affords a fuller capture of the phenomenon of entrepreneurial success.

By concentrating on women, this study provides valuable insights into how to foster and strengthen their entrepreneurial engagement, a matter that is especially critical in light of the growing number of female entrepreneurs today.

From a psychotherapeutic perspective, the findings provide evidence for incorporating cognitive‑restructuring interventions into entrepreneurship support programs. They underscore the importance of assessing entrepreneurs’ self‑efficacy and achievement motivation, as well as the importance of engaging in cognitive work aimed at modifying maladaptive beliefs that erode confidence in one’s capabilities and accomplishments. Entrepreneurship support programs should also involve entrepreneurs’ partners and spouses, raising their awareness and equipping them with psychoeducational tools concerning partner communication and relationship quality. Particular emphasis should be placed on fostering an understanding of the significance of motivational, appreciative, and faith‑affirming messages within couples, thereby strengthening the entrepreneurial engagement of spouses or partners.

ConclusionsIn summary, relational dynamics appear to play a crucial role in entrepreneurial effectiveness, with the relative contributions of various dimensions of partner functioning and communication differing in how they explain entrepreneurial success. Consistent with our initial hypotheses (for both men and women), the strongest predictive value emerged from support specifically tied to the partner’s business activities (i.e., domain‑specific communication). Motivating, appreciating, praising, and actively assisting within a business context foster beliefs related to self‑efficacy and achievement. This constitutes a key pathway for building the psychological capital essential to entrepreneurial activity. Other relational dimensions seem less influential overall, although their importance varies by gender. For female entrepreneurs, a secure foundation in the form of an engaged, supportive partner who shares similar beliefs and preferences proves to be a significant driver of entrepreneurial growth. In contrast, for male participants, this factor, relationship quality, appears to be less significant.

The results of this study provide new evidence of the importance of the family environment for business performance. They unequivocally show that the private and professional areas intertwine such that the quality of the relationship and partner communication can translate into the achievement of entrepreneurial success. This is particularly noticeable among women.

Despite its notable strengths, this study has several limitations that deserve attention. First, the sample comprised only Polish entrepreneurs; therefore, the results cannot be assumed to represent communities where alternative partnership models are preferred. On the other hand, the relational variables and processes that we examined are fairly universal. In many societies, a successful partnership ultimately hinges on mutual support, engagement, intimacy, motivation, appreciation, and so forth. These dimensions are not exclusive to particular social groups or nations. Nevertheless, the model proposed here should be subjected to empirical verification in other cultural settings. In this respect, it offers not only applied value but also replication potential.

Two of the instruments used (the Matched Marriage Questionnaire and the Marital Communication Questionnaire)—while widely employed in Polish family‑psychology research—remain relatively unknown internationally. This limited visibility may hinder intersubjective communicability and validity. Two other tools, namely, the Entrepreneurial Success Scale and the Relationship Support in Business Scale, although promising from a psychometric standpoint, are new instruments that require further research.

Moreover, the absence of comparable studies precludes a dialogue aimed at extracting nuances, similarities, and contradictions with prior findings. This represents a distinct limitation for conducting a mature scientific discussion.

Finally, we should remember that entrepreneurial success is determined by multiple factors; thus, future research should explore models that incorporate additional mediating variables. This study focuses only on two mediators of dependence (self-efficacy and achievement motivation), which does not exhaust the repertoire of psychological variables that can translate into entrepreneurial effectiveness. Further empirical verification is also needed; some of the analyzed paths proved to be statistically nonsignificant, whereas their removal from the model significantly worsened its fitting parameters. This is especially true for the model obtained in the male sample, where pathways from nonspecific communication and relationship quality were found to be nonsignificant. In the present study, communication processes were reduced exclusively to the analysis of their dimensions, namely, support, commitment and depreciation. However, relationship conflict management processes were omitted. Finally, an interesting research area would be to examine the importance of other family influences, namely, the current commitment of parents or in-laws, for strengthening or weakening the psychological potential relevant to the business that entrepreneurs run.

CRediT authorship contribution statementKatarzyna Awruk: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Marcin Waldemar Staniewski: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Wojciech Słomski: Data curation.