Clinical breast cancer decision-making significantly affects life expectancy and management of hospital resources. The aims of the present study were to estimate the time of survival for breast cancer patients and to identify independent factors from healthcare delivery associated with survival rates in a specific health area of Northern of Spain.

MethodsSurvival analysis was conducted among a cohort of 2545 patients diagnosed with breast cancer between 2006 and 2012 from the population breast cancer registry of Asturias-Spain and followed up till 2019. Adjusted Cox proportional hazard models were used to identify the independent prognostic factors of all-cause from death.

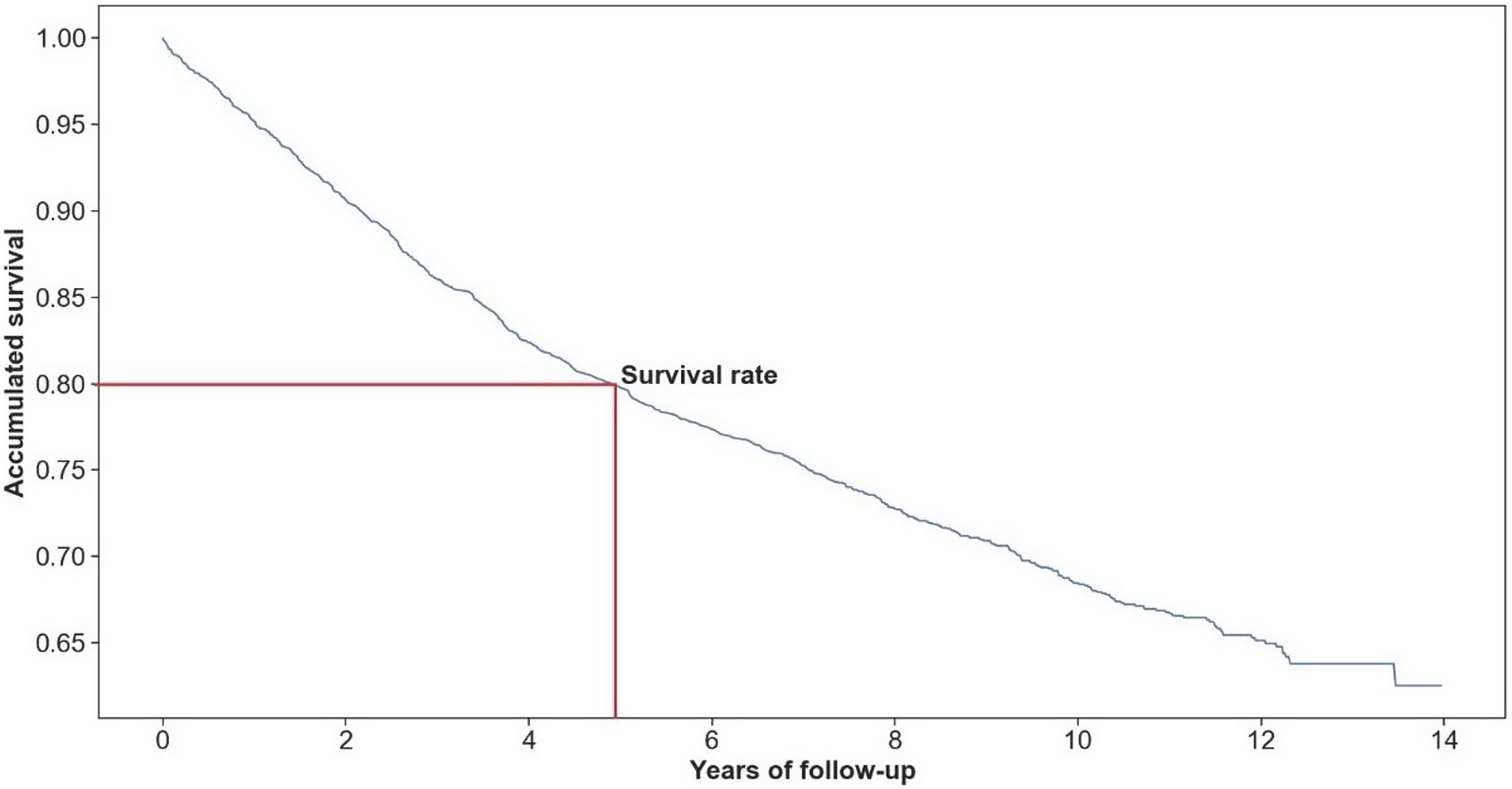

ResultsThe 5-year survival rate was 80%. Advanced age (>80 years) (hazard ratio, HR: 4.35; 95% confidence interval, CI: 3.41–5.54), hospitalization in small hospitals (HR: 1.46; 95% CI: 1.09–1.97), treatment in oncology wards (HR: 3.57; 95% CI: 2.41–5.27), and length of stay >30 days (HR: 2.24; 95% CI: 1.32–3.79) were the main predictors of death. By contrast, breast cancer suspected via screening was associated with a lower risk of death (HR: 0.55; 95% CI: 0.35–0.87).

ConclusionThere is room for improvement in survival rates after breast cancer in the health area of Asturias (Northern of Spain). Some healthcare delivery factors, and other clinical characteristics of the tumor influence the survival of breast cancer patients. Strengthening population screening programs could be relevant to increasing survival rates.

La toma de decisiones clínicas en el cáncer de mama afecta significativamente a la esperanza de vida y a la gestión de los recursos hospitalarios. Los objetivos fueron estimar el tiempo de supervivencia de las pacientes con cáncer de mama e identificar factores independientes de la asistencia sanitaria asociados a la tasa de supervivencia en el área de Asturias (norte de España).

MétodosSe realizó un análisis de supervivencia en una cohorte de 2.545 pacientes diagnosticadas de cáncer de mama entre 2006 y 2012, procedentes del registro poblacional de cáncer de mama de Asturias-España y seguidas hasta 2019. Se utilizaron modelos de riesgos proporcionales de Cox ajustados para identificar los factores pronósticos independientes de muerte por cualquier causa.

ResultadosLa tasa de supervivencia a los cinco años fue de 80%. La edad avanzada (>80 años) (hazard ratio [HR]: 4,35; intervalo de confianza [IC] 95%: 3,41-5,54), la hospitalización en hospitales pequeños (HR: 1,46; IC 95%: 1,09-1,97), el tratamiento en el servicio de oncología (HR: 3,57; IC 95%: 2,41-5,27) y la duración de la estancia >30 días (HR: 2,24; IC 95%: 1,32-3,79) fueron los principales predictores de muerte. Por el contrario, la sospecha de cáncer de mama mediante el programa de cribado poblacional se asoció a un menor riesgo de muerte (HR: 0,55; IC 95%: 0,35-0,87).

ConclusionesExiste margen de mejora en las tasas de supervivencia tras cáncer de mama en Asturias-España. Algunos factores asistenciales y otras características clínicas del tumor influyen en la supervivencia de las pacientes con cáncer de mama. Reforzar los programas de cribado poblacional podría ser relevante para aumentar las tasas de supervivencia.

Breast cancer (BC) is the most commonly diagnosed malignancy in women worldwide. Indeed, BC has surpassed lung cancer as the leading cause of global cancer incidence, with an estimated of 2.3 million new cases in 2020.1 Moreover, BC is the leading cause of death from cancer in the vast majority of countries, leading 685,000 deaths worldwide.1

In high-income countries with robust health systems, patients’ quality of life and survival rates are gradually improving due to improvements in early diagnosis, quality of treatment, and supportive care.2 For instance, the Spanish Network of Cancer Registries has recently reported an increase in BC survival, with an absolute change of +2.3 percentage points in 5-year net survival rates from 2002–07 and 2008–13.3 Nevertheless, the growing burden of BC creates physical, emotional, and financial strain on individuals and puts health systems under growing pressure. Moreover, the persistent poor prognosis observed for some BC women and the certainty that there is room for further improvement call to reinforce actions along the cancer continuum.3 Hence, BC survival estimates are of great importance for patients and clinicians, but also for public health professionals and policymakers, to improve the adequate management of resources.

Some factors can condition the prognosis and evolution of BC and should be routinely studied to find levers for further improvement. From an individual perspective, the early identification of clinical characteristics associated with more aggressive BC and patients with persistence of risk factors beyond BC diagnosis (e.g., tobacco use, alcohol consumption, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, overweight or air pollution),4 followed by evidence-based and tailor-made interventions are still required. From a population perspective, some institutional features, such as the healthcare delivery system and hospital performance indicators, play a significant role and cannot be left out.5

According to the latest data, the observed 5-year survival rate in Spain was 82.0% (81.6–82.5) in women diagnosed during 2002–13 and followed them up to 2015.3 These data place Spain among the countries with better survival rates worldwide, but still far from leading countries such as the USA, Canada or the United Kingdom.6 Asturias is one of the regions in Spain with the lowest BC survival rate, thereby being an ideal place to find factors that will allow closing the gap with the countries providing the best BC care. The objectives of this study were (a) to provide an up-to-date estimate of BC survival in a specific area of north of Spain (Asturias) and (b) to identify independent factors from healthcare delivery that affect survival. Thus, this study provided a scheme to design interventions that can decrease BC mortality and improve the quality of health attention for women with BC.

Subjects and methodsStudy design and participantsWe conducted a survival analysis among a cohort of women diagnosed with BC from 2006 to 2012 in Asturias (Northern Spain) and retrospectively followed up until the end of 2019. We obtained data from the state population-based cancer registry, one of the oldest cancer registries in Spain, which collaborates with the International Agency for Research on Cancer by data provision. First, we selected BC cases with a primary malignant neoplasm, using the International Classification of Diseases, Oncology, 3rd edition (ICD-O-3),7 topographical codes C50.0 to C50.9. Then, we merged this information through the hospital discharge reports of the Minimum Basic Data Set (MBDS) from the reference public hospitals of the eight health areas of Asturias (Jarrío, Cangas de Narcea, Avilés, Oviedo, Gijón, Arriondas, Mieres, and Langreo). This data has been validated for data quality and overall methodology by the Spanish Ministry of Health.

We created an anonymous database using Python 3 with biopsy or surgery confirming BC cases. We started with 2812 cases. The cases had data on the cancer registry and the MBDS. Subsequently, we chose to exclude all but one case of BC diagnosed in the same woman to avoid an overestimation of survival due to multiple BC (n=164; 27 metachronous and 137 synchronous). When a woman had two or more diagnoses of BC, we selected the first diagnosis if both cases were metachronous (i.e., the time between diagnoses >6 months). However, if they were synchronous, we chose the case with the worse prognosis (i.e., more advanced stage and-or greater treatment intensity). We excluded 37 BC cases because they were duplicates, suggesting coding errors. Finally, we excluded the 10 cases due to missing information on the national identity document because we could not check the survival status. As a result, we analyzed 2545 BC women.

The Research Ethics Committee of Asturias (Spain) approved the study protocol with approval number 137/17. We performed the study following the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments.

Mortality ascertainmentWe performed a computerized search for the Spanish National Death Index to evaluate all-cause mortality.8 We accessed this information through request. This database contains updated information on the vital status of all residents in Spain. Information regarding death dates after 2006 was available for 99.9% of the cohort. Therefore, censoring was set at the date of death or the end of follow-up (31 December 2019), whichever occurred first. In addition, we defined survival time as a period between the diagnosis of disease and death or the end of patient follow-up, and we used a binary censoring variable to indicate whether a patient died of BC or for other reasons.

Study variablesThe principal outcome variable for survival analysis was the time to death for all-cause mortality censored (in years). In addition, we considered some characteristics related to healthcare delivery: BC suspected via a population screening program (yes/no); hospital size, measured by the number of beds9; hospital wards; hospital length of stay, calculated from the day of hospitalization to day of discharge; and readmissions within the first 30 days after initial hospital discharge. Finally, we also considered several demographic and clinical variables: age at BC diagnosis; history of another cancer; BC staging according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer and International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition (ICD-O-3)7; and treatment modalities, including surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormone therapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy.

Data analysisStatistical analyses were performed with Python (version 3.2). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

We used the Cox proportional-hazard and stratified Cox models for the time-to-death data to analyze the influence of selected variables on survival time. The median follow-up time was 8.89 years. We fitted several Cox models to obtain significant covariates, eliminating non-significant variables using the “stepwise” procedure. The variables included in the model were age at BC diagnosis (<50, 50–64, 65–79, ≥80 years), history of another cancer (yes/no), BC stage (local, regional, advanced), types of BC treatments (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormone therapy, immunotherapy, targeted therapy, other therapy), BC suspected via screening (yes/no), hospital-size (level I: <200 beds, level II: 200–499, level III: 500–999, level IV: ≥1000 beds),9 hospital wards (gynecology and obstetrics, general surgery, oncology, other hospital wards), length of stay (<7, 7–30, >30 days) and readmissions (yes/no). Furthermore, we used the Kaplan–Meier method to estimate the unadjusted survival function.

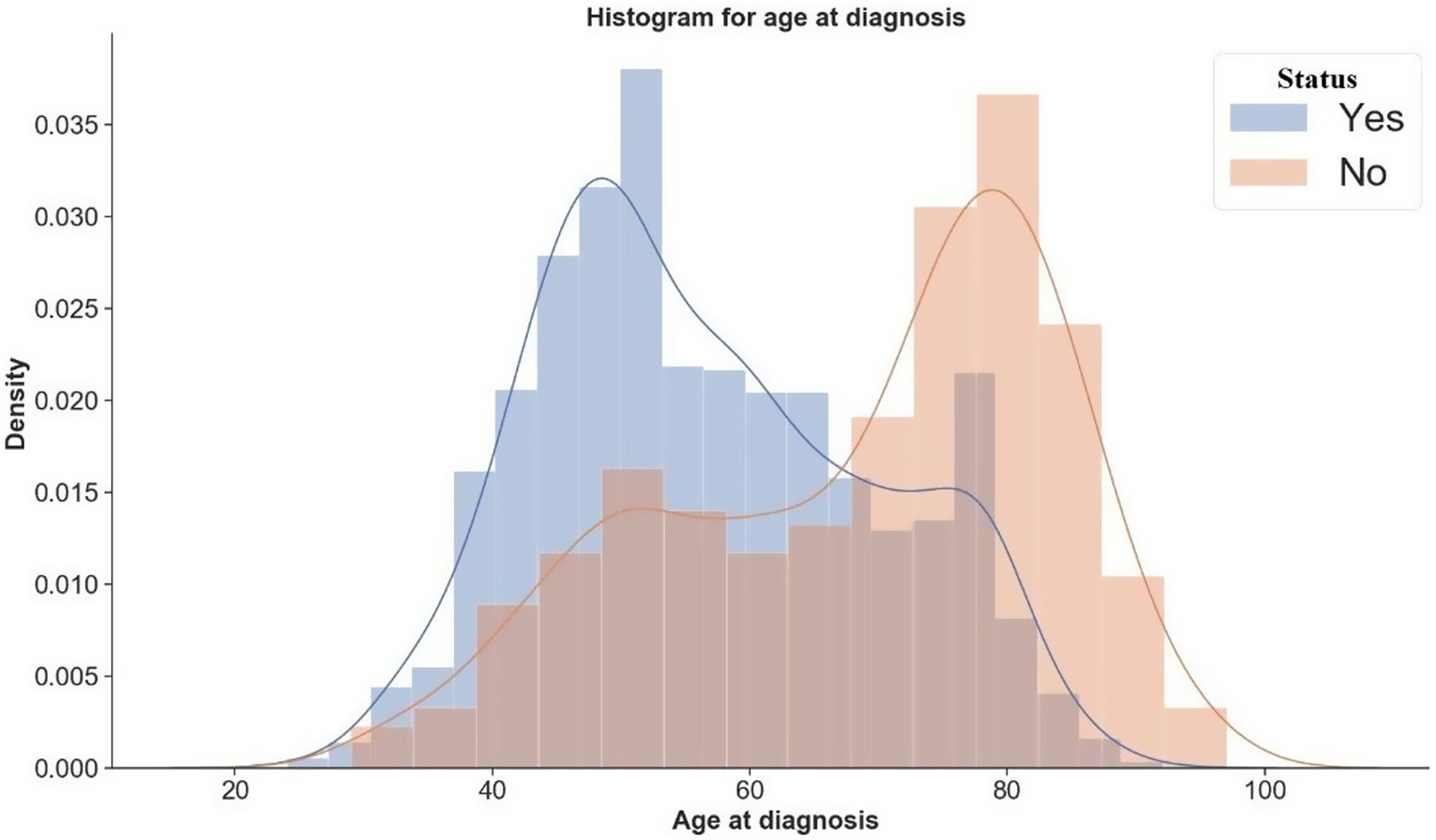

The Cox proportional hazard model assumes that the hazard ratio for any two specifications of predictors is constant over time. We used the Schoenfeld residuals to verify whether the model adheres to the proportional hazard assumption. Additionally, the stratified Cox model is a modification of the Cox proportional hazard model that allows for control by stratification of a predictor that does not adhere to the proportional hazard assumption. We adjusted a predictor that does not satisfy the proportional hazard assumption by stratification. In this case, we allowed to include the covariates in the model without estimating its effect.10 In contrast, we corrected the predictors that agree with the proportional hazard assumption by their inclusion in the model. In this way, we estimated the hazard ratio value for the effect of variables in each stratum. Consequently, in this study, we fitted either Cox proportional hazard model or the stratified Cox model according to the proportional hazard assumption. We used the C-index, the probability of concordance between the predicted and the observed survival, as evaluation criteria of the performed model.11 Finally, we used a Gaussian Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) to estimate the underlying distribution. The KDE uses an optimization via the Scott rule of thumb, a data-based procedure for choosing an optimal bandwidth.12 This data procedure allows us to gauge the likely outcome of age at BC diagnosis (Fig. 1).

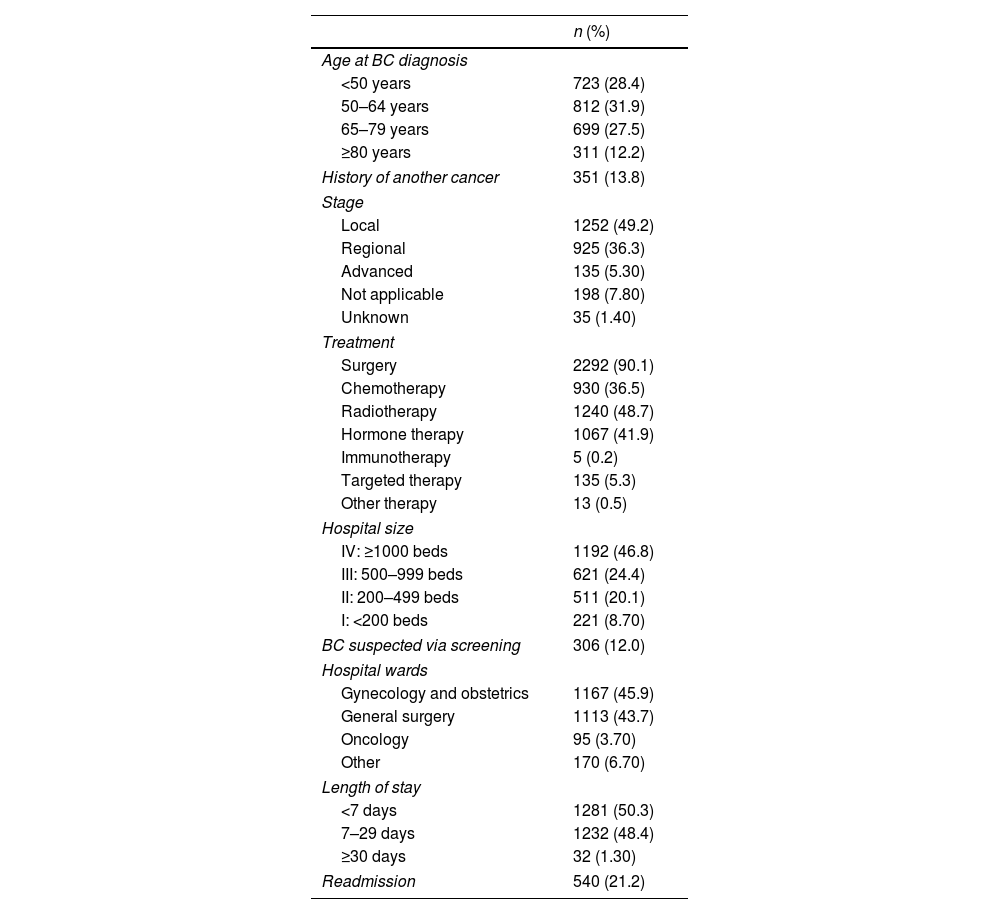

ResultsTable 1 shows the main characteristics of BC patients (n=2545). The largest age group for BC diagnosis was 50–64 years. According to the BC stage, 49.2% of cases were local, 36.3% regional, and 5.30% advanced. In our sample, surgery was the most frequent treatment modality (90.1%), followed by radiotherapy (48.7%). In 12.0% of patients, BC diagnosis occurred after a mammographic suspicion through a population screening program. Finally, regarding healthcare delivery variables, the hospital-size IV treated 46.8% of patients, the mean length of stay was 8.07 days (±8.64), and 21.2% of the patients had hospital readmissions.

Characteristics of BC patients from a population-based cancer registry, Asturias-Spain, according to demographic, clinical and health care delivery variables.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age at BC diagnosis | |

| <50 years | 723 (28.4) |

| 50–64 years | 812 (31.9) |

| 65–79 years | 699 (27.5) |

| ≥80 years | 311 (12.2) |

| History of another cancer | 351 (13.8) |

| Stage | |

| Local | 1252 (49.2) |

| Regional | 925 (36.3) |

| Advanced | 135 (5.30) |

| Not applicable | 198 (7.80) |

| Unknown | 35 (1.40) |

| Treatment | |

| Surgery | 2292 (90.1) |

| Chemotherapy | 930 (36.5) |

| Radiotherapy | 1240 (48.7) |

| Hormone therapy | 1067 (41.9) |

| Immunotherapy | 5 (0.2) |

| Targeted therapy | 135 (5.3) |

| Other therapy | 13 (0.5) |

| Hospital size | |

| IV: ≥1000 beds | 1192 (46.8) |

| III: 500–999 beds | 621 (24.4) |

| II: 200–499 beds | 511 (20.1) |

| I: <200 beds | 221 (8.70) |

| BC suspected via screening | 306 (12.0) |

| Hospital wards | |

| Gynecology and obstetrics | 1167 (45.9) |

| General surgery | 1113 (43.7) |

| Oncology | 95 (3.70) |

| Other | 170 (6.70) |

| Length of stay | |

| <7 days | 1281 (50.3) |

| 7–29 days | 1232 (48.4) |

| ≥30 days | 32 (1.30) |

| Readmission | 540 (21.2) |

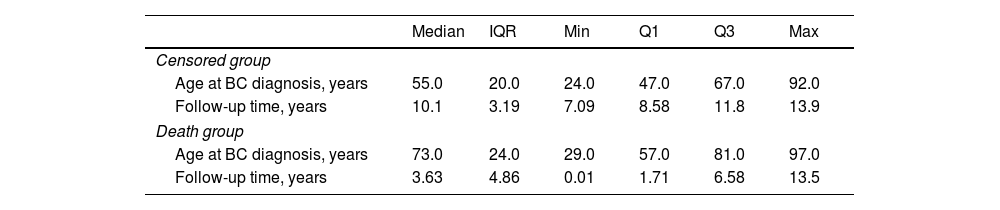

Table 2 shows statistics for the censored and death group. By comparing the median values, we found that women from the censored group were younger at BC diagnosis than women from the death group. Therefore, we used a Gaussian KDE to estimate the underlying distribution. Moreover, Fig. 1 shows no overlapping, suggesting that age at BC diagnosis is a considering factor in the patient's likelihood of survival.

Statistics of BC patients for censored and death group.

| Median | IQR | Min | Q1 | Q3 | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Censored group | ||||||

| Age at BC diagnosis, years | 55.0 | 20.0 | 24.0 | 47.0 | 67.0 | 92.0 |

| Follow-up time, years | 10.1 | 3.19 | 7.09 | 8.58 | 11.8 | 13.9 |

| Death group | ||||||

| Age at BC diagnosis, years | 73.0 | 24.0 | 29.0 | 57.0 | 81.0 | 97.0 |

| Follow-up time, years | 3.63 | 4.86 | 0.01 | 1.71 | 6.58 | 13.5 |

IQR: interquartile range; Q: quartiles.

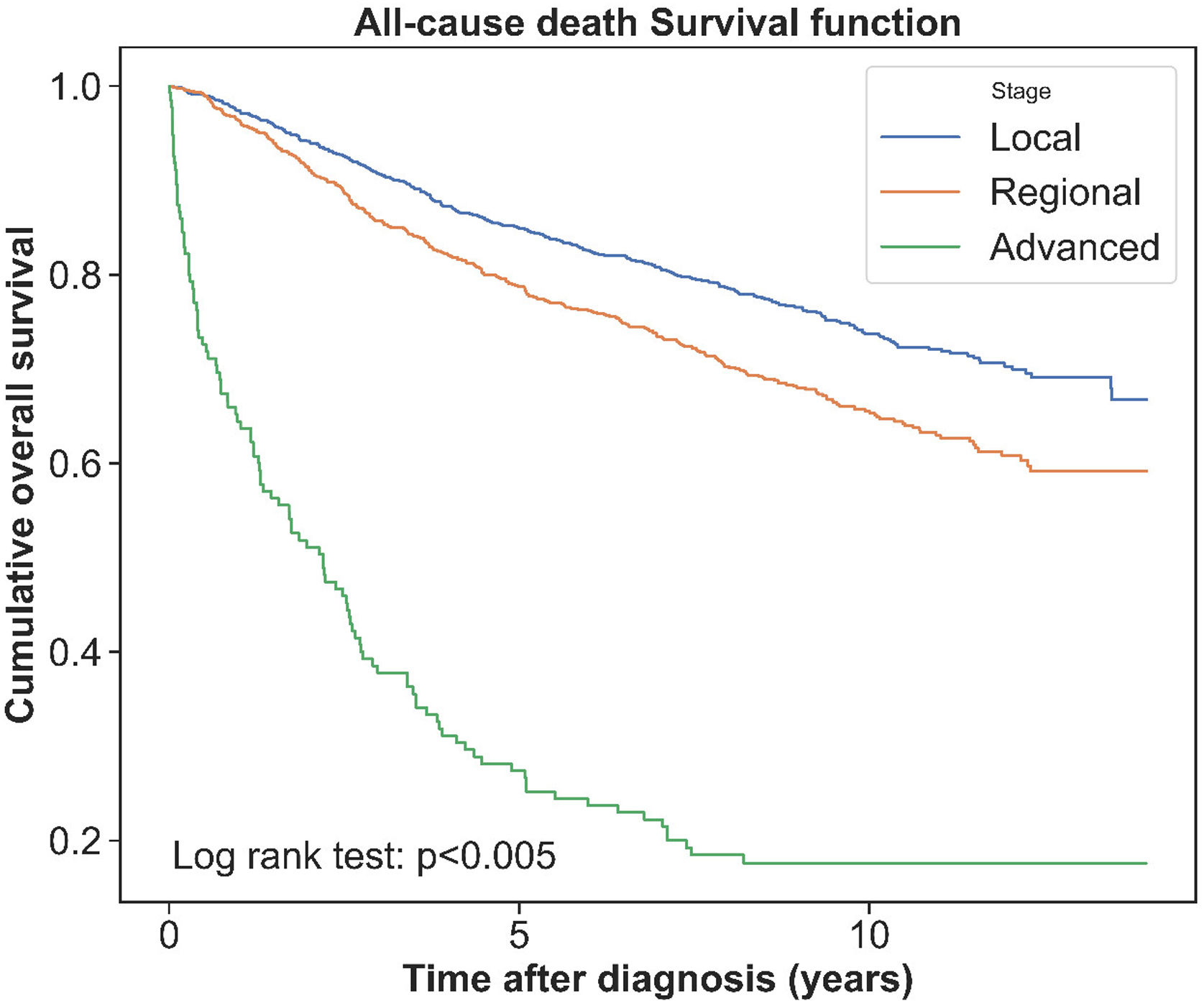

Overall, 808 (31.7%) women with BC died of all causes during complete follow-up and 515 (20.0%) during the first five years after BC diagnosis; therefore, the 5-year survival rate was 80.0%. Fig. 2 shows the crude survival curve, and Fig. 3 depicts survival rates according to the BC stage. Survival rates were differed for each stage group, with the advanced stage corresponding to the lowest survival time and survival rate.

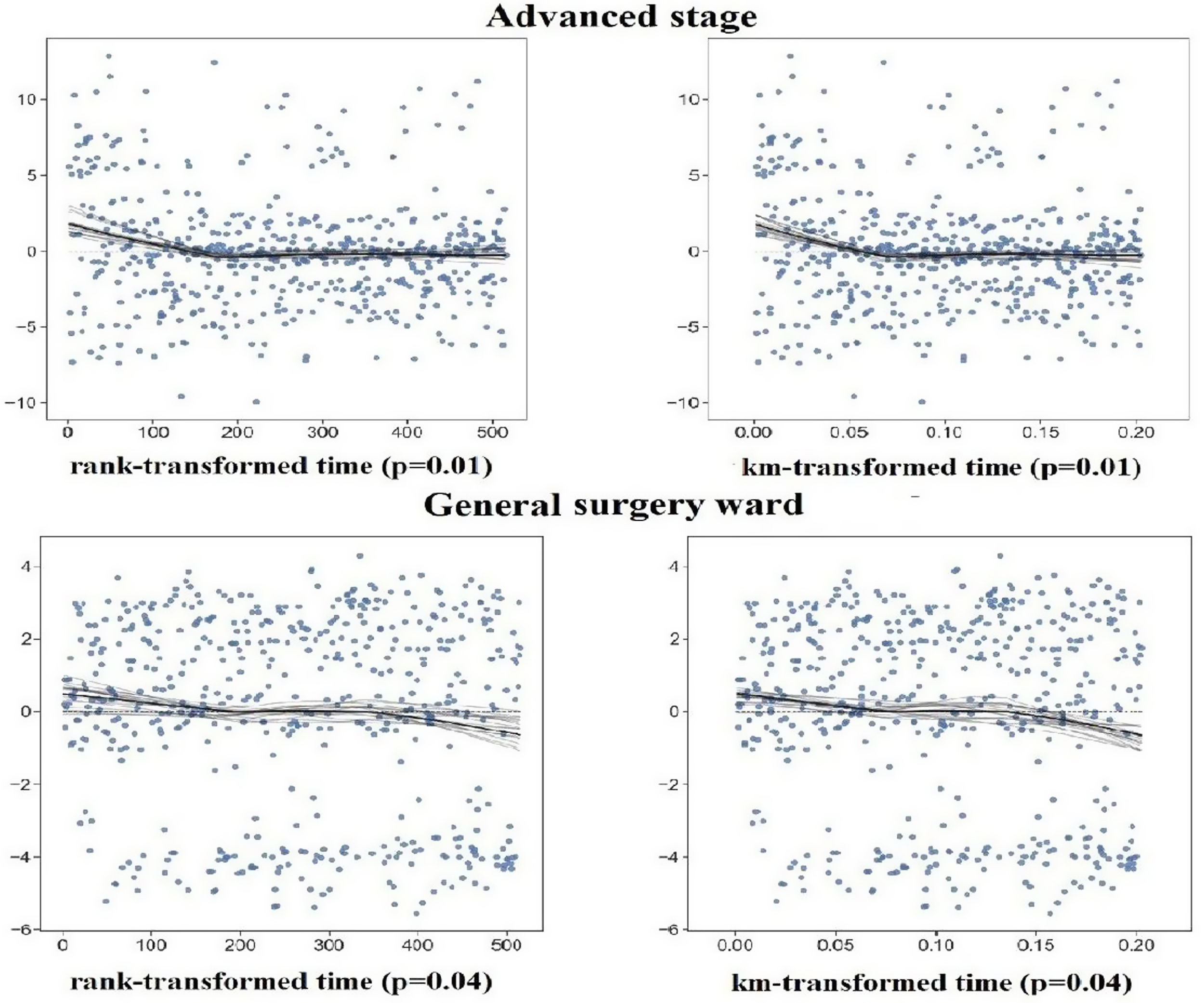

Supplementary Table 1 shows the results of testing the proportional hazard assumption. Additionally, Supplementary Figure 1 shows a plot of residuals for the variables that failed the proportional hazard assumption for the first 5-year follow-up. Considering residual plots and chi-square values related to variables, the categories of advanced stage, general and digestive wards, surgery treatment, and hormone therapy do not satisfy the proportional hazard assumption for the first 5-year follow-up. Moreover, the categories 65–79 years at BC diagnosis, ≥80 years at BC diagnosis, advanced stage, surgery, chemotherapy, and hormone therapy do not satisfy the proportional hazard assumption for complete follow-up.

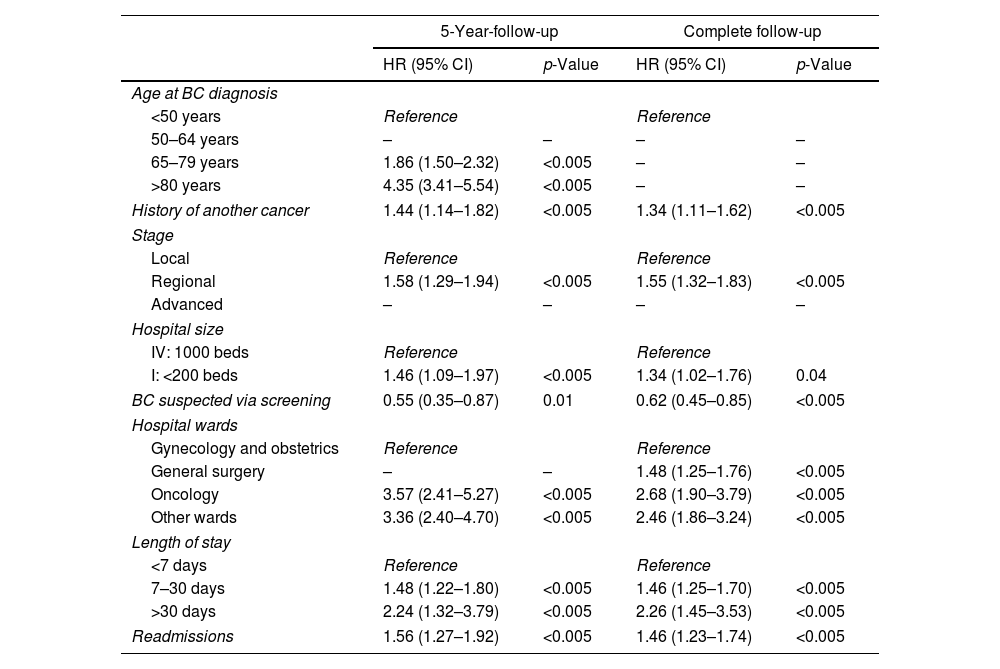

As reported by the results of the Cox model in Table 3, several variables were associated with an increased risk of all-cause death among women with BC, both at 5 years of follow-up and during the complete follow-up. Among healthcare delivery variables, having been hospitalized in oncology or other wards and length of stay above a month were the most important explanatory factors of death. By contrast, BC suspected via screening was associated with a lower risk of all-cause death (HR=0.55, 95% CI: 0.35–0.87 at 5-year-followup and HR=0.62; 95% CI: 0.45–0.85 after complete follow-up). The C-index value was 0.79, indicating good prediction accuracy.

Variables associated with all-cause of death of BC patients from multivariate Cox proportional hazard model.

| 5-Year-follow-up | Complete follow-up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-Value | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Age at BC diagnosis | ||||

| <50 years | Reference | Reference | ||

| 50–64 years | – | – | – | – |

| 65–79 years | 1.86 (1.50–2.32) | <0.005 | – | – |

| >80 years | 4.35 (3.41–5.54) | <0.005 | – | – |

| History of another cancer | 1.44 (1.14–1.82) | <0.005 | 1.34 (1.11–1.62) | <0.005 |

| Stage | ||||

| Local | Reference | Reference | ||

| Regional | 1.58 (1.29–1.94) | <0.005 | 1.55 (1.32–1.83) | <0.005 |

| Advanced | – | – | – | – |

| Hospital size | ||||

| IV: 1000 beds | Reference | Reference | ||

| I: <200 beds | 1.46 (1.09–1.97) | <0.005 | 1.34 (1.02–1.76) | 0.04 |

| BC suspected via screening | 0.55 (0.35–0.87) | 0.01 | 0.62 (0.45–0.85) | <0.005 |

| Hospital wards | ||||

| Gynecology and obstetrics | Reference | Reference | ||

| General surgery | – | – | 1.48 (1.25–1.76) | <0.005 |

| Oncology | 3.57 (2.41–5.27) | <0.005 | 2.68 (1.90–3.79) | <0.005 |

| Other wards | 3.36 (2.40–4.70) | <0.005 | 2.46 (1.86–3.24) | <0.005 |

| Length of stay | ||||

| <7 days | Reference | Reference | ||

| 7–30 days | 1.48 (1.22–1.80) | <0.005 | 1.46 (1.25–1.70) | <0.005 |

| >30 days | 2.24 (1.32–3.79) | <0.005 | 2.26 (1.45–3.53) | <0.005 |

| Readmissions | 1.56 (1.27–1.92) | <0.005 | 1.46 (1.23–1.74) | <0.005 |

In our BC women's cohort from Asturias, Spain, 4 out of 5 patients survived at least 5 years after diagnosis. However, during follow-up, the risk of all-cause death was higher among older women diagnosed with regional BC and a history of another cancer. Regarding healthcare delivery variables, being hospitalized in wards different from gynecology and obstetrics, in small hospitals, with longer stay, and being readmitted for a complication were prognostic factors of worsened survival. Otherwise, being diagnosed via the BC population screening program was associated with a lower risk of death.

Age at BC diagnosis is probably the most determinant factor for all-cause death,13–15 although it is supposed that younger women usually have more aggressive BC. Regarding hospital characteristics, our findings showed that patients in the oncology ward, general surgery, and level-I hospital were significant factors that impacted BC survival among the cohort. Until 2014, the gynecology and obstetrics service of the reference hospital of the Asturias region (the Central University Hospital of Asturias), which provided the most BC number of cases to our study, was in charge of the clinical management of BC women. Most probably, for this reason, in our study, the gynecology ward obtained better results on survival than other wards. Although we adjusted the analyses for hospital size, the admission ward might not be the influencing variable but rather having been treated in the referral hospital. The study of hospital characteristics and BC survival in the California Breast Cancer Survivorship Consortium16 found that African American women had higher survival when receiving initial care in American College of Surgeons hospitals versus other hospitals. These findings suggest that more specialized hospitals achieve better survival rates.

Regarding healthcare delivery variables, hospital readmissions were also predictors of worse survival. Miret et al.17 found that surgical and medical complications increased the risk of readmissions, adjusted by detection mode and treatments received. Accordingly, providing more intensive surveillance of women with treatment complications may help to reduce further readmissions associated with the disease. Furthermore, in our study, patients with 30 days or more of length of stay had a higher risk of death in compared with women with shorter hospitalizations. Patients who require lengthy and more intensive treatment may need prolonged stays,18 suggesting a worse prognosis. Although malignant neoplasms are usually in the top 30 diseases with extended stays,19 the effective management of length of stay is possible with a sustained effort to manage patients with BC. In any case, the relevance of this finding relay on the opportunity to identify patients with a higher risk of death more than to try to improve survival by shortening the stays. It is necessary to use the same argument for the finding referring to hospital wards since admission to an oncology service may only indicate greater severity of BC.

The result of our study with the most relevant practical implication is related to the protective effect of participating in screening programs. This result is consistent with those in the scientific literature.20 A plausible explanation may be a combination of improving early diagnosis rates, with a consequent quicker entry into specialized care of BC women, and higher detection of insidious cancers when a curative treatment is still possible.21,22 Therefore, encouraging recruitment and adherence of women to population-based BC early detection programs could be the best investment to increase survival. It is well known that BC rates screening participation and affinity are acceptable in Spain (around 70 and 90%, respectively) and meet the standards from European guidelines,23–25 but they can be better. For instance, women with disadvantaged socio-economic situations and immigrants had significantly lower participation rates.24,25 In any case, detection rates via screening in our study were strikingly lower. Although in some studies, the percentage of BC detected in population-based screening programs is similar to our figure,26 in most countries, BC detection rates via screening are not usually below 25%.27 Indeed, a study by Natal et al. reported that the program in Asturias diagnosed around 50% of BC.28 The most compelling reason for this finding is that our study included a considerable number of women outside the screening target population (50–69 years), which would have reduced the overall detection rate via screening. However, we cannot exclude the information bias when using cancer registry data.

Finally, we found a lower overall unadjusted 5-year follow-up survival rate (80%) for BC patients compared with other studies conducted in Spain. For instance, according to a population-based study, the 5-year survival rate after a BC diagnosed between 2000 and 2013 in Spain was 82.0%.3 In addition, Parés et al.29 found a 5-year survival rate of 82.6% in Barcelona during 2000–2014. Chirlaque et al.,30 using data from nine Spanish population-based cancer registries, reported a 5-year survival rate of 82.6% among women diagnosed with BC between 2000 and 2007. Baeyens-Fernández et al.,31 estimated a 5-year survival rate in Granada of 83.7% in a cohort of women with BC diagnosed in 2010–2012. This finding is consistent with data recently published in the “Atlas of Cancer Mortality in Portugal and Spain 2003–2012”,32 which depicted an unexpected excess of mortality among BC women in Asturias compared with the rest of Spain. Then, a potential hypothesis was that over-mortality in Asturias might be due to lower participation in BC population screening programs, which was now a core finding of our study. In the international context, a report from the American Cancer Society in 2015–2016 showed a 5-year survival rate of 89%.33 In a study conducted in European countries in 2013, the 5-year relative survival rate ranged from 69 to 84%.34 Moreover, the meta-analysis conducted by Maajani et al.35 estimated a 5-year survival rate of 71.0% in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. In addition, in a study conducted in developing countries, the 5-year survival rate varied from 52% in India to 82% in China.36 An important factor that may account for the differences in survival rates among women with BC might be the improvement or lack of it in the health systems in some countries. Thus, this may result in late diagnosis, improper treatment of patients, and screening programs. Furthermore, our findings could be age-related. Asturias is the Spanish region with the highest population aging in Spain and one of the oldest in Europe. Finally, in survival analyses that included all age groups at BC diagnosis, when the group of women over 80 years is large, as in our study, the overall 5-year survival rate results necessarily lower.29

Our study had several limitations. We conducted this study based on secondary data from medical records, and an incomplete hospital information dataset could cause the loss of patient follow-up. Moreover, we lack information about essential variables such as socioeconomic, molecular patterns, and lifestyle. Finally, in this study, we did not include women treated on an outpatient basis who did not require hospital admission during the follow-up, as they were not part of the MBDS. For this reason, we could exclude women with a higher probability of survival, which could have underestimated our survival rates. Despite these limitations, we determined some prognostic factors related to healthcare delivery and estimated the survival probabilities of BC patients in our cohort.

In conclusion, there is room for improvement in survival rates after BC in Asturias, Spain. Several healthcare delivery factors negatively influenced the survival of BC patients, although it is hard to unlink them from some clinical characteristics of inadequate prognosis. The most relevant was being hospitalized in wards different from gynecology and obstetrics, in small hospitals, with longer lengths of stay, and readmitted for a complication. By contrast, in this study, women diagnosed via the BC population screening program had a lower risk of death; therefore, early detection of BC could be crucial to increasing survival rates. These findings could help provide evidence-based information to healthcare authorities and others to design interventions that can decrease the mortality of BC and improve the quality of BC healthcare.

Author's contributionsConceptualization: A. Lana; Software: N. Robles-Rodríguez; Formal analysis: N. Robles-Rodríguez; Data curation: N. Robles-Rodríguez; Writing – original draft: N. Robles-Rodríguez; Writing – review & editing: N. Robles-Rodríguez, A. Llaneza-Folgueras and A. Lana; Visualization: N. Robles-Rodríguez, A. Llaneza-Folgueras and A. Lana; Supervision: A. Lana and A. Llaneza-Folgueras. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethical approvalThe Research Ethics Committee of Asturias (Spain) approved the study protocol with the approval number 137/17.

FundingThis research was funded by Secretaría Nacional de Ciencias y Tecnología de Panamá and Instituto para la Formación y Aprovechamiento de Recursos Humanos (270-2018-932).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Thanks are due to L. Tórrez for her suggestions and J. Robles for recommendations with the original manuscript.