Psychological interventions for people with chronic pain increasingly target emotion dysregulation as a contributing factor in psychological comorbidity and pain intensity. The acceptability of these interventions remains uncertain. This qualitative study examined the acceptability of internet-delivered dialectical behavioural therapy for chronic pain (iDBT-Pain), an emotion regulation skills-focused (ERSF) intervention aimed at enhancing emotion dysregulation. iDBT-Pain integrates DBT skills training, and pain science education, in a hybrid guided and self-directed online format.

MethodsWe conducted 18 semi-structured interviews with participants enrolled in a Randomised Controlled trial which showed iDBT-Pain significantly improves emotion dysregulation, depression symptoms and pain intensity. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and deductively analysed according to a theoretical framework of acceptability.

ResultsParticipants perspectives supported the integration of emotion regulation skills within holistic chronic pain treatment, identifying their efficacy to enhance emotion regulation capabilities and reduce pain intensity. There was also acceptance of the online group-based delivery, and hybrid therapist-guided/self-directed approach.

DiscussionFindings highlight the need for clinical assessment to gauge client readiness for an emotionally focused approach, assess sensitivity to others’ emotions in a group setting, and ensure personalisation of digital components to enhance engagement. These findings have implications for developing iDBT-Pain and for ERSF interventions, particularly those delivered online and to groups. The findings also underscore the role of emotion regulation as a key mechanism in chronic pain, supporting research that advocates for its deeper exploration as a central psychological target in chronic pain mental health treatment.

Emotion regulation refers to our ability to manage our emotional state, to influence the intensity, duration, and frequency of emotions (Gross, 2002). Emerging evidence demonstrates that individuals with chronic pain exhibit a diminished capacity to regulate emotions (Frumer, Harel & Horesh, 2023; Aaron et al., 2020; Lumley et al., 2011; Linton & Shaw, 2011; Linton, 2013), contributing to psychological comorbidity and worsening pain intensity (Lumley et al., 2011; Linton, 2013; Koechlin et al., 2018). A recent systematic review and meta-analysis uncovered that emotion-regulation-skills-focused (ERSF) interventions reduce pain intensity and depressive symptoms compared to usual treatment, and reduce pain interference compared to cognitive behavioural therapy (Norman-Nott et al., 2024).

It is theorised that enhancing emotion regulation transforms cognitive abilities to comprehend and express emotions adaptively and, in doing so, benefits psychological dimensions and pain-related outcomes (Linton & Shaw, 2011). However, measurement of emotion regulation is rarely included in clinical trials of psychological interventions for people with chronic pain (Norman-Nott et al., 2024; Karst, 2024). Hence, while ERSF interventions demonstrate positive benefits for this population, there is limited data to understand whether improvement in emotion regulation underscores the therapeutic benefits and effects on pain-related symptoms.

To address this gap, a recent randomised controlled trial (RCT) investigated internet-delivered dialectical behaviour therapy for chronic pain (iDBT-Pain) (Norman-Nott et al., 2025), an ERSF intervention based on DBT skills training, an evidence-based intervention for emotion dysregulation (Linehan & Wilks, 2015). Building on preliminary trials of DBT for chronic pain (Boersma et al., 2019; Linton & Fruzzetti, 2014; Linton, 2010; Barrett et al., 2021; Sysko, Thorkelson & Szigethy, 2016; Norman-Nott et al., 2022), the iDBT-Pain RCT compared this intervention to treatment-as-usual, prioritising emotion regulation as the primary outcome. It also updated DBT skills for pain-related concerns and integrated pain science education on the mind-body connection and the relationship between emotions and pain (Kang et al., 2021; Butler & Moseley, 2003). Findings revealed significant improvement in emotion regulation at both 9 and 21-weeks, with benefits extending to significant reductions in depression symptoms at both time points and in pain intensity at 21-weeks (Norman-Nott et al., 2025).

While these findings are promising, the acceptability of interventions focusing on emotions rather than pain reduction remains, to our knowledge, understudied in the ERSF literature. A focus on changing emotions may feel invalidating to individuals with chronic pain (Burke, 2019; Driscoll et al., 2021). Therefore, understanding the positive and negative aspects of these approaches may help guide the development of interventions focused on the emotional experience of chronic pain. While our groups pilot study of iDBT-Pain provided preliminary evidence supporting intervention acceptability, the small sample size warranted further investigation to gather more diverse perspectives and enhance generalisability (Norman-Nott et al., 2022). Moreover, incorporating qualitative research into RCTs enhances the understanding of treatment efficacy and may reveal the mechanisms underlying change (Cheng & Metcalfe, 2018; Lewin, Glenton & Oxman, 2009). For example, feedback regarding acceptability of iDBT-Pain may elucidate what contributes or detracts from engagement, and therefore what may determine the effects of the intervention.

The current study aimed to evaluate acceptability of iDBT-Pain with participants in the treatment arm of the iDBT-Pain RCT. We sought to evaluate participants’ commentary, with a key focus to understand the acceptability surrounding, emotion regulation as the target of the intervention, the group-based sessions, and hybrid guided/self-directed internet delivery. Acceptability was defined as the intervention's appropriateness for participants, based on their thoughts and feelings across seven domains: affective attitude, ethicality, intervention coherence, burden, perceived effectiveness, self-efficacy, and opportunity costs (Sekhon, Cartwright & Francis, 2017). Within each domain, barriers and facilitators to engaging in the intervention were explored to identify and inform successful uptake of iDBT-Pain.

MethodsStudy designA qualitative research design employing a deductive thematic approach was applied to evaluate participant perceptions of acceptability of iDBT-Pain through semi-structured interviews. A deductive top-down, theory-based approach was chosen to generate detailed information about specific aspects of the intervention specified a-priori (Braun & Clarke, 2006), using the seven domains from the theoretical framework of acceptability (TFA): affective attitude, ethicality, intervention coherence, burden, perceived effectiveness, self-efficacy, and opportunity costs (Sekhon, Cartwright & Francis, 2017). Thus, this study aligns with a post-positivist research paradigm, which supports the use of theory-driven qualitative methods to explore participant experiences within a structured framework (Braun & Clarke, 2025).

This qualitative study was embedded in an RCT of iDBT-Pain (Norman-Nott et al., 2025), registered on the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12622000113752) and detailed in a published protocol (Norman-Nott et al., 2023). Ethics approval was obtained from the University of New South Wales Human Ethics Committee (HC220078). The report of this study is guided by the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) (O’Brien et al., 2014).

Participants and recruitmentParticipants in the iDBT-Pain RCT were adults (≥18 years) who self-identified as currently having chronic pain (pain persisting ≥ 3-months) rated a minimum of 3 out of 10 for the past seven days, without psychotic or personality disorders, or dementia, with access to the internet, fluent in reading and writing English, and living in Australia.

A requirement for participation in this qualitative study was participation in the active arm of the iDBT-Pain RCT. A total of 45 participants were randomised to the intervention arm (Norman-Nott et al., 2025), with the first 24 to complete the intervention invited to provide qualitative feedback. Of these 24, 4 voluntarily withdrew, before the start of intervention (n = 2), and after two sessions (n = 2) and were uncontactable for an interview. However, where possible details were sought about the intervention experiences up to the point of withdrawal and are included in the results. All remaining participants (n = 20) were invited by email a maximum of three times by a member of the research team (NN-N) to arrange a 90-minute semi-structured interview conducted via video conference. A sample size of 15–20 participants was targeted, to attain enough breadth and depth of information (Braun & Clarke, 2021). Written informed consent for participation in this qualitative study was given at the time of consenting to the iDBT-Pain RCT and confirmed verbally prior to the semi-structured interview.

Research teamThe research group included a registered psychologist, professor with PhD, and specialist in chronic pain intervention (SMG), two research fellows with PhD with a focus on chronic pain, applied research, and technological intervention (YQ, NH-S), a physiotherapist with PhD and interest in the study of chronic pain and qualitative research (RRNR), a clinical researcher, psychology graduate and PhD candidate with a background in technology (NN-N), a researcher with PhD and interest in the design and application of technologies for improving mental health (JSu), a user experience researcher with PhD experienced in formative studies investigating technological intervention for mental health (JSc), and a professor with PhD skilled in chronic pain, psychological research, and intervention (JHM). The varied professional backgrounds of the researchers led to diverse reflection during the analysis and interpretation of the qualitative data.

Patient involvementWe received input from people with chronic pain in our design and development of the intervention. We carefully assessed the burden of the trial on participants with oversite by the trial management group. We intend to disseminate the main results to trial participants, to the public, and to relevant user-led advocacy organisations.

The iDBT-Pain interventionThe iDBT-Pain intervention utilises evidence-based protocols to train in mindfulness, emotion regulation and distress tolerance skills from DBT according to the DBT Skills Training Manual (Linehan, 2015), and adapted to address chronic pain specific challenges. For example, inspired by Milton Erickson’s approach to pain perception (Erickson, 1967), we adapted the DBT mindfulness techniques to observe pain without judgment. Participants were encouraged to assign a name or colour to their pain, fostering a more objective perspective while engaging in mindfulness-based DBT practices. Emotion regulation and distress tolerance skills were also modified with pain-specific examples via informational videos, such as illustrating how anger can increase pain intensity. Pain science education was also incorporated into the intervention based on findings demonstrating its role in fostering trust, engagement and adherence in digital interventions for chronic illness (Karekla et al., 2019). Pain science education explained the evidence about chronic pain development, the brain's role in emotional processing, and how neuroplasticity, through psychological interventions, can help unlearn pain signals over time (Kang et al., 2021; Butler & Moseley, 2003).

There are three key elements in the delivery of iDBT-Pain: (1) the iDBT-Pain sessions, consisting of eight 90-minute group-based sessions delivered via video conference on Zoom; (2) the iDBT-Pain app, accessed daily on a smart device such as a smartphone; and (3) the iDBT-Pain handbook, a 130-page printed book sent by mail to each participant. Therefore, the iDBT-Pain interventions is a hybrid model of therapist-guided sessions with self-directed skills-based learning which extends a traditional blended model, whereby in-person sessions are supported with self-directed internet-delivered materials (Erbe et al., 2017; Wentzel et al., 2016). This approach was chosen to leverage the benefit of both self-and therapist-guided interventions. Namely, self-directed interventions are related to meaningful changes in chronic pain symptoms (Barlow et al., 2002), potentially through feelings of empowerment to self-manage treatment (Nicholas & Blyth, 2016), while, therapist-guided sessions provide the opportunity to clarify and discuss concepts and can mitigate attrition (Bender et al., 2011).

Six of the iDBT-Pain sessions focused on learning the chronic pain tailored DBT skills integrated with the pain science education. Additionally, we included an introductory session in the first week to establish the group environment, and a concluding session in the last week to consolidate the skills learning. Weekly text messages served as reminders for session attendance, and to practice frequently using the app and handbook. If a participant could not attend the iDBT-Pain session live, a video recording of the missed session was provided by secure link. The iDBT-Pain sessions were delivered by a primary therapist, a registered psychologist (SMG), and an assistant therapist, a PhD candidate qualified in DBT skills from the Linehan Institute (NN-N). The therapeutic environment was designed as supportive and nurturing, to provide a sense of inclusion and trust, important to enhance therapeutic outcomes (Furnes, Natvig & Dysvik, 2014), and to enable group discussion useful to facilitate and enhance learning in those with chronic pain (Dysvik & Stephens, 2010). The iDBT-Pain app and handbook allowed participants to self-manage their learning and generalise skills usage to their daily lives (Fig. 1). A multimodal approach integrating both digital and print formats was adopted to leverage the respective benefits of each modality and accommodate diverse participant preferences in engaging with the content. While printed materials allowed for deeper engagement, including note-taking and content highlighting, and helped alleviate eye strain associated with prolonged online engagement, digital resources offered convenience for shorter tasks and facilitated easy access to video content (Johnston & Salaz, 2019). Accordingly, the app which was accessible on participants smart devices, focused on step-by-step tasks to train skills and the printed handbook provided pain science education plus worksheets to practice skills. A full description of the iDBT-Pain intervention is accessible in the publication of the RCT (Norman-Nott et al., 2025) .

Data collection and interview guideData was collected using a semi-structured interview guide (see supplemental files) according to the seven domains of acceptability outlined in the TFA (i.e., affective attitude, burden, ethicality, intervention coherence, opportunity costs, perceived effectiveness, and self-efficacy) (Sekhon, Cartwright & Francis, 2017). The TFA is used to understand how people consider a healthcare intervention to be acceptable, based on their thoughts, feelings, attitudes, and beliefs about an intervention. Closed questions were used to capture participant’s general perceptions about a domain, followed by open-ended questions to elicit further explanation. For example, one of the closed-ended questions exploring self-efficacy asked, “Will you continue to use the skills going forwards?”, which was then followed up with “How confident are you in your abilities to use the skills?”. Prompts were also developed for each question should it be necessary to ask participants to clarify or expand. The interview guide was developed by NN-N alongside RRNR who is knowledgeable about qualitative research and healthcare interventions for chronic pain, and reviewed by SMG who is experienced in the iDBT-Pain intervention and in the development of chronic pain mental health interventions.

All interviews were conducted by NN-N using the video conferencing platform, Zoom, a platform familiar to the participants because they used it during the iDBT-Pain intervention. Video conference was also feasible compared to in-person interviews given that participants were in different locations across Australia. With participant consent, the interviews were recorded, firstly to eliminate interviewer-recall bias, and secondly, it enabled the interviewer to focus on the participant, therefore maintaining appropriate attentiveness (Kelly, 2010). To ensure cybersecurity during the semi-structured interview, access was restricted through the Zoom platform waiting room function, whereby the interviewer granted access to admit the participant into the interview. All interviews lasted from 60 to 90 min, after which, audio recordings were auto transcribed using Otter Pro (Otter, 2023), before being manually checked for accuracy by simultaneously reviewing the audio and written transcripts. Transcriptions were then stripped of any identifiable participant information, assigned a unique identification code, and then imported into NVivo 14 (Lumivero, 2023), a qualitative data management software, for analysis. All recordings and transcriptions were saved on a password protected server accessible only to the researchers involved in the study.

Data analysisData analysis was conducted on the interview transcripts in accordance with a structured approach for thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Data analysis was conducted in parallel with the data collection. This analytic process involved reading and re-reading the transcripts; systematically identifying excerpts that correspond with the pre-defined codes of the TFA and then searching for patterns in the data and organising the data into themes representing the primary perspectives.

The first author (NN-N) completed an in-depth read and re-read of the transcripts to become familiar with the data and to get an overview of each participant’s opinions about iDBT-Pain. Illustrative statements and excerpts from the transcripts were subsequently discussed between the authors (NH-S, NN-N, RRNR, and SMG) before creating a codebook according to the TFA domains (see Table 1), which is useful to improve coding consistency when there are multiple authors’ perspectives (Guest, MacQueen & Namey, 2012). In creating the codebook, we classified “facilitators” or “barriers” to the acceptability of iDBT-Pain under each of the TFA domains. A facilitator was defined as a statement that either improved or, at the very least, did not diminish the perceived acceptability of iDBT-Pain. Conversely, a barrier was identified as a statement that may negatively affect the perceived acceptability of iDBT-Pain.

Codebook according to the domains of the theoretical framework of acceptability.

Note. TFA = theoretical framework of acceptability.

Data were systematically analysed while applying the codebook by NN-N. Two authors (NH-S and YQ) independently scrutinised the first author’s coding and reached a consensus after a discussion with the primary analyst (NN-N). Themes arising from the codes were then summarised in a matrix by NN-N, and scrutinised by RRNR, SMG, YQ and NH-S. This process was iterative to ensure that the interpretations of the themes were credible. Our analysis refrains from emphasizing the frequency of a theme, and instead focuses on the meaning in response to the research question about acceptability (Monrouxe & Rees, 2020). Nevertheless, we incorporate an indication of how frequently participants expressed a similar perspective, utilising terms such as "many," "several", "some," and "a few" in the results (Neale, Miller & West, 2014). Replication of the themes until no new themes were identified was determined to indicate data saturation (Cleary, Horsfall & Hayter, 2014).

ResultsEighteen of the 20 participants contacted to conduct the interview, responded and agreed to participate. Two did not respond after three approaches via email. The demographic and clinical characteristics of participants included in this study are presented in Table 2. The male/female sex ratio was reflective of the participant sample in the iDBT-Pain clinical trial, including 83.3 % females (N = 15) with a median age of 51.5 (range: 27–67) years. The average attendance of the iDBT-Pain sessions was 85.23 %, with participants watching missed iDBT-Pain sessions via video recordings, meaning all received 100 % of the intervention content. Twenty facilitator themes and 15 barrier themes were identified across the seven domains of the TFA. Quotes reflecting responses for each theme within each domain are presented in Table 3. In the text, the quotes are reported using the letter “Q” and the number reported in Table 3 (e.g. Q1 indicates Quote 1).

Demographic and participant characteristics.

Note.aParticipants that missed a zoom session watched a video recording to catch-up on missed content before the next session.

Quotes from participants.

Note. TFA = theoretical framework of acceptability, Q = Question, P = Participant.

The domain of affective attitude captures participants’ feelings about the iDBT-Pain intervention. Several participants commented that they felt validated, understood, and less alone by connecting with others during the group sessions (Q1–6). Participant 8 said “I get comments like, well, you're young. So how can you have pain … then I get upset. I like that it wasn't just me that was younger than everyone else” (Q5). While Participant 7 mentioned that the group environment was a unique experience, "hearing their perspectives….we’re all connected in this in this way….I found that the thing that I hadn't had before” (Q3). Additionally, several participants liked the content delivery, describing it as either motivational or informative, expressing enjoyment in the variety of mediums to learn the skills and appreciation of the conversational style (Q7–13). Participant 16 indicated an appreciation of the DBT skills saying “it was just such an amazing programme. I've told so many people about it, and DBT for chronic pain in general” (Q11). While Participant 18 commented about the app, “I did find it funny how you can trick yourself to find some comfort in having a conversation with a machine. But I did actually like that approach” (Q7). There were several other mentions that being in a group with others with chronic pain encouraged and enhanced learning (Q14–19), with Participant 1 commenting that they “learned through that experiential stuff…not just the skills themselves, but people's experience of the skills” (Q14).

A few participants highlighted barriers related to affective attitude suggesting that greater opportunities for individualised interaction either with the therapists, or with other participants potentially in-person would have been beneficial (Q20–23). Participant 11 commented “in-person people do get to interact a little bit more and you can develop closer relationships” (Q20). Additionally, some participants, including one that withdrew from the trial, experienced transient levels of distress during the iDBT-Pain sessions over other participants experiences (Q24–28). Participant 1 commented “that kind of supportive environment is helpful, but it also can be in itself a form of distress because you resonate so closely” (Q25), while Participant 3 said “I found it a little bit overwhelming, but I think for me, sometimes I can take on other people's pain when I hear their experiences” (Q26).

EthicalityEthicality refers to the extent that an intervention is a good fit with an individual’s value system. It was commented by some that the delivery of the group sessions was in a non-judgemental, compassionate, and authentic manner (Q29–32). Participant 16 said “The way you guys did it, it was just very non-judgmental, it was very inviting. And I think that's the way you've got to approach things. Because chronic pain is a highly debilitating and insidious and stressful time for people and it heightens your emotions. So having compassion and kindness is so important. And I think you guys did that really well” (Q29). Participant 4 commented on how they valued this approach, “it’s an outlet, but you know that you’re not going to be judged (Q32). That in itself is therapeutic” (Q32). The uniqueness in comparison to other interventions was noted, with Participant 8 commenting “with some of those programs, I feel….why can't I do it right. And it would be negative…where I just feel it's something wrong that I did, but yours didn't make me feel that way…so that was good” (Q30). Participant 13 noted that “people shared stuff, and other people were being supportive” (Q31), indicating the encouraging environment of the group sessions.

Some participants mentioned that the intervention aligned with their beliefs or faith practices (Q33–37). For example, Participant 14 commented “The wisdom within this program is perfectly in accord with my Buddhist practice” (Q33), and Participant 17 described how the intervention met their needs, “I wanted something that was a drug free approach to helping manage my mindset. I wasn’t after a miracle cure, or a miracle pill” (Q36). Additionally, several participants valued the opportunity for learning and focus on the emotional experience of pain (Q38–41). For example, Participant 8 valued the knowledge of others, “having people that were like, of all ages, I felt like they had a lot of wisdom that I could draw from” (Q41). Participant 3 commented on the value of learning new concepts, “As you started to talk about the changes in the brain, that's when you’re going to get people on board to say oh, it’s a neurological change. It’s not just a psychological thing” (Q38), while Participant 17 stated that “the emotional part aligns with what I value” (Q39).

Regarding ethicality barriers, Participant 3 commented “that initial thought about mindfulness…. that maybe you're telling me again, that it's in my head….I think that people need to work through to get to a point where they're accepting of the mindfulness process, there is a bit of a barrier there” (Q42). A few participants (one male and one female sex) commented that the emphasis on emotions might be off-putting for males (Q43–44), because females, as Participant 9 said, “are more in touch with their feelings, we're allowed to feel” (Q44). A few participants highlighted concerns around the interventions respect for their personal time (Q45) and the time of others (Q46), with Participant 11 commenting that “I did find that in the Zoom meetings that I felt sometimes I was saying too much, and not letting other people have a turn (Q45).

BurdenBurden refers to the amount of effort that is required to participate. Comments from some participants highlighted that the expectations of the intervention were realistic and achievable (Q47–51). Participant 8 said that “it was easy to just apply it to my everyday life and wasn’t overwhelming (Q47), while Participant 17 mentioned, “my psychologist, my pain specialist….and my physio they all really supported it, and they thought it was really good….it just kind of aligned with everything” (Q51). It was further mentioned by several participants, that participating over the internet aided accessibility, allowing participation from almost anywhere which is especially beneficial when living with persistent pain (Q52–59). Participant 4 mentioned “I have a specially designed chair that I'm sitting in now that helps. Now, if you're going to a physical location, that 90-minute session could become torture……Turning up to a boardroom, sitting in a chair, that might be horribly uncomfortable” (Q58). While Participant 7 said “Having the sessions on Zoom was good… being able to do it from your phone, like one time I was waiting to go on a ferry and sitting in the car” (Q54). Comments from a few participants demonstrated that the benefits of participation outweighed any burden (Q60–62), with Participant 4 explaining “there was no burden at all…It was obvious, it is designed to help and that is its purpose. So I can come in and I can benefit from that” (Q61).

On the other hand, a few participants felt that fitting the intervention into their lives was difficult (Q63–65), with Participant 8 saying “I felt bad when I wasn't engaging with the app as much as I could” (Q64). Commentary from several also highlighted issues with the app and a desire for a more personalise experience in the app (Q66–71). For example, Participant 8 commented, “I did like the activities in the app. But then I found that when I did them, they were like the same each time” (Q68). Participant 1 felt that the app “could improve [in] functionality….from having notifications or reminders” to complete the skills (Q68), while Participant 3 said “I think there just needs to be a space for the individual to be able to explain the pain in the situation that they're in….. I think when you're in pain, you feel like you need to explain that and say this is my situation… Just a space for someone to be able to individualise it” (Q70).

Opportunity costsThe domain of opportunity costs captured the extent that benefits or values may be given up or gained by engaging in the intervention. A few participants commented that the requirement to actively participate in the intervention was an advantage, and distinguished iDBT-Pain from other programs that lack specific direction (Q72–73). For example, Participant 17 said “I find that most of the pain programs that I've done in the past have been quite passive. And so having to actively engage with people and material it was a really big selling point for me, and I feel like that worked really well” (Q73). Furthermore, many participants valued learning emotion regulation skills (Q73–79). Participant 5 mentioned that “the emotional pain has been my struggle, like for over six years. The pain I could cope with, but the emotional pain was harder. I was really glad you were tackling that” (Q74). While Participant 15 said “It's important to target emotions, I've said right from day one” (Q78), and Participant 10 commented “when you've got more emotional skills, like the ones you gave us, you do relax more, you feel more empowered” (Q79).

The focus on emotions also distinguished iDBT-Pain from other interventions. Participant 13 commented, “I think in cognitive behavioural therapy any focus on emotions is completely lacking… they only do the thinking part…..we don't want to ignore the emotions they are there…..they just come out of nowhere, I'll be doing something. And it just appears and I have no idea why” (Q75). Furthermore, comments from a few participants highlighted the value of online sessions (Q81–83). For example, Participant 12 suggested that “more people would appreciate doing it this way. You see lots of people being forced to go back to pain clinics, who've got terrible pain, who can't sit at all, who are then expected to go every day for five days for four hours at a time. Some people just can't do that. So it's great. Excellent” (Q81). While Participant 11 commented that “a little bit of the distance is helpful in some way, like not actually being in a room with somebody (Q82). It's got that sort of extra layer that makes you that bit more likely to say things that you might not if someone's sitting right next to you”, suggesting an advantage over an in-person setting (Q83).

However, a few participants, including one that withdrew from the trial, expressed the view that some of the skills taught during the iDBT-Pain intervention resembled those taught in other interventions (Q84–85). Participant 13 said “the topics that were covered was stuff that I already knew…. I was a little bit disappointed, but at the same time… they were a slightly different presentation… so it was a good reminder and refresher for me to use those skills” (Q84). Additional feedback from a few participants highlighted that the groups could have been smaller in size to encourage greater interaction (Q86–87). Furthermore, Participant 1 raised a concern that the technological nature of the intervention might be a barrier to engagement, “I spend so much time in technology, I try to not do a lot” (Q88).

Perceived effectivenessPerceived effectiveness refers to participants' impressions of whether the intervention effectively achieved its intended goals. Commentary from some participants showed a decrease in pain (Q89–92). For example, Participant 14 said “I do go through quite strong pain episodes…I’ll hit eight, nine out of 10, at least four or five times a week… And some of those times, I’ve been able to notch it back down to sort of five, six, just by calming the farm” (Q89). While Participant 18 commented “My sciatica and my nerve pain, all but completely disappeared for parts of the program….it seems to have an effect on my pain” (Q91), and Participant 13 said “I noticed during the program that my burning pain was less, and I had less breakthrough pain” (Q91). Several participants observed enhanced abilities in regulating and coping with negative emotions and living with chronic pain (Q93–98). For example, Participant 17 commented “I was sitting in a place of anger and hostility about my pain situation…what this pain program did was, it just gave me some more tools to be able to respond better to a situation that I couldn’t change” (Q93). While Participant 6 said “my ability to deal with them and register them and recover from them when I’m getting emotional or angry or triggered. Being able to try and stop that process, be able to calm myself down, refocus myself so I don’t escalate the emotions” (Q97). Additionally, several participants commented on the effectiveness of iDBT-Pain compared to other interventions (Q99–104). Participant 12 said “This approach is more effective compared to other things I’m doing for my pain because it’s given me tools that I’m using regularly. Whereas before I didn’t have anything. In moments where I have flare ups and things like that, I’m now able to use the tools that you gave us” (Q102).

A few participants identified the intervention duration as a barrier to effectiveness, commenting that it could have been longer giving more time to learn the skills and evaluate the effects (Q105–106). Participant 7 suggested “maybe it could have been where you sort of wean off going from every week, and then every fortnight and then every month, or then every three months” (Q105). While Participant 1 said “my pain fluctuates so much. It’s hard to know in the short term…I do think they’re helping me to create a safer state within my own body. And I think that hopefully that translates to less pain…..So I think it’s probably too early to tell” (Q106). Additionally, Participant 18 commented on the need to continually practice the skills, “I’ve not done a lot of the skills recently. So it’s kind of fallen off….my pains kind of come back. So I was thinking oh, gosh, it’s a lifestyle, isn’t it?….[but] I’m not stressed about it, because I know…I’ll just pick up the app….to get back into it again, and make that time” (Q107).

Self-EfficacySelf-efficacy refers to the participants' belief in their ability to fulfill the requirements of the intervention. It was mentioned by some, that the various components of the intervention (app, handbook, and sessions) were user-friendly (Q108–111). For example, Participant 11 said of the app, “I found it very, very easy to use and quite pleasant. Like it's a sort of a fun kind of thing to do rather than a too hard task thing. And I'm not really very good at technology stuff” (Q109). While Participant 1 commented on the sessions “The zoom was super easy. It was interesting how it enabled people to be comfortable and turn their cameras off if they needed to help with their pain or lie down on the couch. So that, I think was really positive for people” (Q111). Additionally, it was commented by some participants that they could do the skills (Q112–116) and would continue to train in them (Q117–121). Participant 18 said “I feel really confident. Even if I take some time away from it and need to revisit it, I think it's almost like a lifelong skill set” (Q116). While Participant 10 commented about continuing to use the material to practice the skills ongoing, “I just like to kind of dip into the booklet a few times a week…. And I might just look at one page….and might think, I haven't done that for a while or remind myself of the skills” (Q121).

A potential barrier to self-efficacy was commentary indicating that there needed to be either more time, resources, or support (Q123–131). For example, Participant 7 said “to really ingrain some of the new really useful tools into my life. I feel like I need more time” (Q125), while Participant 1 said, “We could probably spend more time on those skills…I think learning them is one thing, but the challenge of implementing it…is hard for any skills that you use” (Q126). While Participant 2 said of the app “I found it a little bit difficult a few times where I’m like, Okay, you’re giving me this prompt, but I don’t know how to answer it. But I kind of just had to muddle through to get to the end” (Q128). Participant 13 said “If there's a space on the app for reflection, like a reflection diary kind of journal entry. I think there just needs to be a space for the individual to be able to explain the pain in the situation that they're in” (Q129). Additionally, Participant 14 noted that mobility issues could result in varying degrees of ability to perform the skills, “If I was completely bed bound, there's a lot of things in there that I couldn't do” (Q132).

Intervention coherenceThe domain of intervention coherence gauges participants' grasp of the intervention and its functioning. Comments from some participants demonstrated that they recognised the role of negative emotions in exacerbating pain severity, indicating an understanding about the underlying concepts guiding the approach employed in iDBT-Pain (Q133–136). For example, Participant 10 commented “It's just crucial to deal with emotions as well as the pain. It's that element of dealing with the whole person. And not just looking at the symptom of pain” (Q133). While Participant 8 said “it's just a really vicious circle with pain, because obviously, when you have pain, it affects your emotion, and then your emotion gets worse. And that makes your pain worse. But then it's like after you've had it for so long, and it becomes chronic. It's like what came first? And what's causing what now?” (Q134). Moreover, some mentioned understanding how the skills and tools operate (Q137–141). For example, Participant 3 commented “I always thought that mindfulness was more about distraction or breathing through pain. I never really understood that the brain changes when you go through mindfulness….So I didn’t actually understand that mind body connection, from a neurological standpoint” (Q140).

On the other hand, several participants noted a potential barrier to their understanding of the intervention (Q142–147). Participant 18 said “I would have liked [the trainer] to explain more about the real mechanics and neurotransmitters and that background material” (Q143), While Participant 3 commented that “at the beginning, there was a lot about mindfulness. And that was really important to be guided through why mindfulness is important, how it can decrease your pain, how it can make changes in your brain. But I think that's probably where I was a little bit lost just in terms of how my pain fits in there” (Q147).

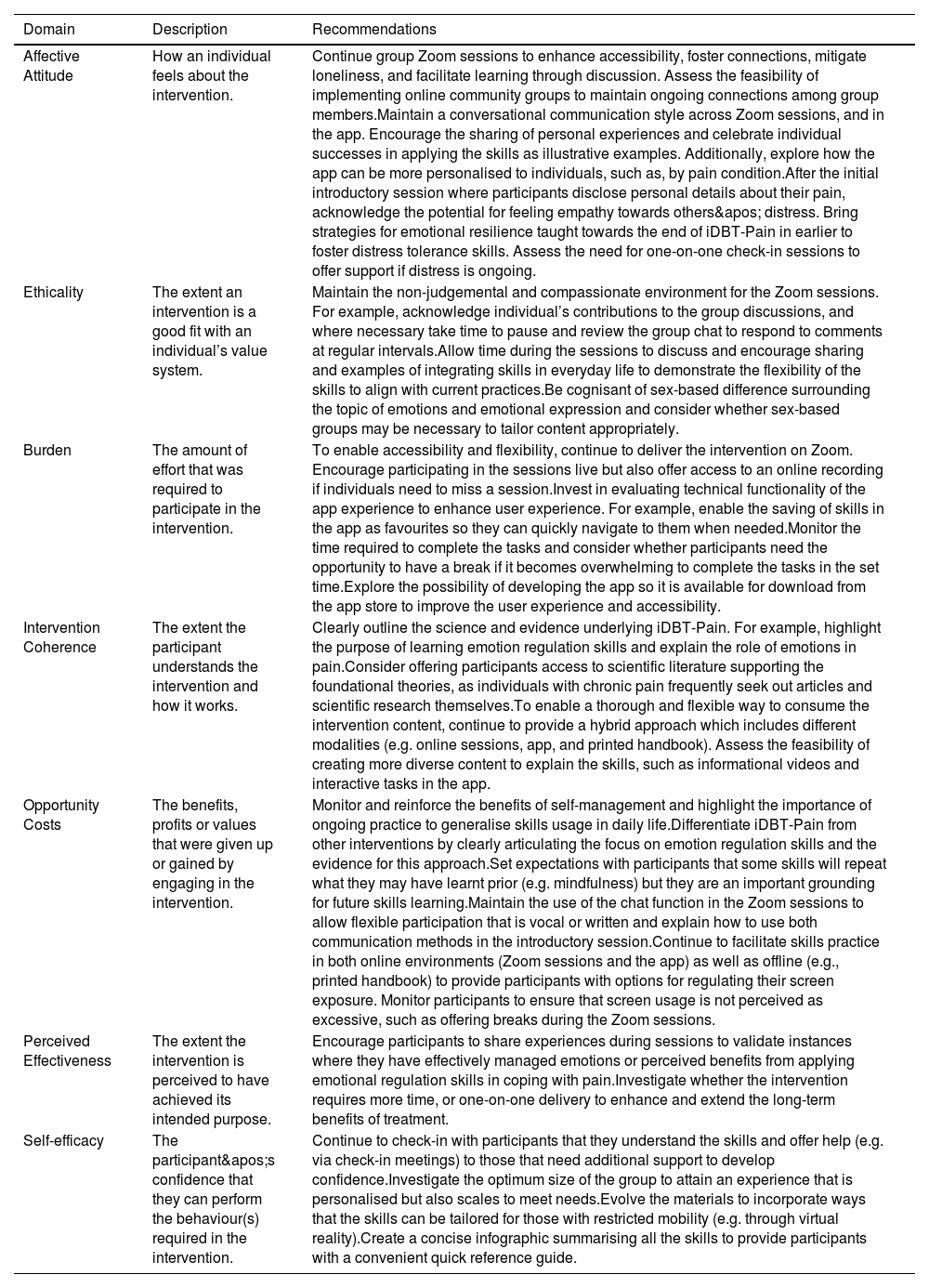

DiscussionThis study aimed to understand the experiences of participants receiving iDBT-Pain, to determine acceptability for people with chronic pain. Using a deductive thematic analysis in accordance with a theoretical framework, we explored participants commentary to identify barriers and facilitators to engaging in the intervention. A key focus was understanding acceptability regarding targeting emotion regulation, as well as acceptability of the group-based sessions and the hybrid guided/self-directed internet delivery. Our findings have implications for developing iDBT-Pain and for other interventions focused on the emotional experience of chronic pain, particularly those that are delivered online and to groups. Recommendations to refine iDBT-Pain are highlighted in Table 4.

Summary of recommendations for iDBT-pain.

Participant commentary on affective attitude, ethicality, and burden indicated that emotion regulation skills were well-received and aligned with the needs of the chronic pain population. iDBT-Pain was perceived as effective to improve emotion processing and expression while also reducing pain intensity, reinforcing its acceptability (Sekhon, Cartwright & Francis, 2017). These findings support our clinical trial (Norman-Nott et al., 2025), and broader research linking emotion regulation abilities to psychological and pain-related outcomes (Koechlin et al., 2018; Norman-Nott et al., 2024; Boersma & Flink, 2025; Lumley & Schubiner, 2019), while indicating a need to further explore the mechanistic relationship between pain, emotion regulation and psychological factors (e.g. depression and anxiety) in people with chronic pain.

Despite broad support to target emotions, some participants asserted that emotions may be perceived as feminine, potentially making ERSF interventions less appealing to males. This perception could explain the predominantly female sample in this study and other ERSF trials (Norman-Nott et al., 2024). Gendered norms related to individuals response to pain, stemming from genetics, hormones, and societal expectations may contribute to females perceiving pain as more emotionally driven (Samulowitz et al., 2018), making them more inclined to engage in ERSF interventions. Additionally, a Lancet review reported that women with chronic pain often face greater invalidation (e.g., from healthcare providers) (eClinicalMedicine, 2024), potentially increasing emotion dysregulation and their need for an emotionally focused approach. Nevertheless, both male and female participants comprehended the concepts underlying iDBT-Pain, that emotions and pain are intimately related, and demonstrated confidence in applying the skills. However, pain science education about ERSF interventions appeared fundamental to this comprehension, echoing the literature that individuals with chronic pain want to understand their condition (Bhana et al., 2015) and the interventions they receive (Karekla et al., 2019). For example, demonstrating the rationale behind mindfulness to aid with emotional reactiveness was key to mitigate invalidation of chronic pain, potentially because there may be a perception, that the biomedical aspects of chronic pain are being dismissed when focusing on emotions (Burke, 2019; Driscoll et al., 2021).

Considering these findings, we recommend clinical assessment evaluates individuals’ requirements, particularly to consider the depth of information needed to rationalise the intervention, alongside an evaluation of any preconceived ideas about the emotionality of pain. To aid this, new educational and training initiatives for clinicians may be key in successful translation of ERSF approaches into practice. Additionally, integrating ERSF approaches within a holistic treatment model that also addresses biological and social factors may help prevent feelings of invalidation associated with focusing on the emotional aspects of chronic pain.

Group-based sessionsEvaluation of participants commentary identified positive responses to the group-based sessions which simultaneously influenced several acceptability domains including, affective attitude, ethicality, and opportunity costs. Consistent with prior studies exploring group environments (Hestmann, Bratås & Grønning, 2023; Andersen et al., 2014; Alldredge, Burlingame & Rosendahl, 2023), including a pilot study investigating an online group intervention (Mariano et al., 2019), the group environment led to feeling validated and socially connected. Participants also appreciated the non-judgmental, compassionate, and supportive culture created by the therapists. Factors understood to encourage active participation and create a nurturing therapeutic alliance (Dysvik & Stephens, 2010).

However, the group environment was not positive for everyone, with commentary from a few, including one that withdrew, highlighting emotional distress upon hearing others talk about their pain and emotions. Thus, while, self-disclosure plays a crucial role in group interventions, enabling problem identification, learning opportunities (Swiller, 2009), and a forum for sharing ideas (Furnes, Natvig & Dysvik, 2014), a group environment may not suit all people with chronic pain. Based on these findings, including an evaluation of whether an individual is suited to a group environment as part of intake assessment appears to be a particularly important for emotionally focused interventions. This evaluation may be all the more necessary when the intervention is online, like iDBT-Pain, because facial cues and body language indicating distress are less apparent compared to in-person environments where these cues are more visible to the attending clinician (Eccleston et al., 2020).

Hybrid guided/self-directed internet deliveryParticipants responses related to the acceptability domains of burden, self-efficacy, and opportunity costs, supported internet-delivery and a hybrid guided/self-directed approach that blended guided video conferencing sessions with the iDBT-Pain app and printed handbook. Consistent with findings from other studies (Mariano et al., 2019; Booth et al., 2022), online sessions enhanced accessibility, thereby reducing intervention burden, and eased feelings of self-consciousness and anxiety associated with group-based in-person interventions. In agreement with other research (Walumbe, Belton & Denneny, 2021), the chat function in the sessions enabled individuals anxious about vocally contributing to still participate. Given frequent comorbid anxiety among individuals with chronic pain, and the role this has in worsening health related symptoms (Asmundson & Katz, 2009), enabling environments that minimise anxiety and supports contributions may be particularly important for engagement, adherence, and treatment outcomes.

Related to the acceptability domain of perceived effectiveness, the effects on pain and emotions required frequent practice. While a few were unable to maintain their practice in the app, it was also noted that continued access to the app and handbook meant skills could be easily picked up again in the future.

These results align with previous research emphasising the impact of empowering individuals with chronic conditions to self-manage treatment (Barlow et al., 2002; Schroeder et al., 2018). However, we caution that some individuals may need more support in learning the skills and implementing them, especially depending on the competing demands for time, such as work, family and other responsibilities. Relatedly, it was commented that more personalisation in the app (e.g. by pain condition), would encourage engagement, and skills learning. These findings align with the literature that personalisation enables individuals to access content most relevant for them, in turn driving greater engagement and intervention efficacy (Borghouts et al., 2021; Schroeder et al., 2020). Considering these findings, a hybrid approach incorporating both guided and self-directed elements, appears to be appropriate for delivery of an ERSF intervention for people with chronic pain. Although, we caution that some individuals may need more than eight weeks to complete the training, and therefore intervention delivery may be spread out over a longer time span.

Strengths and limitationsThis study benefits from a robust methodology, including a pre-published protocol, a structured interview guide to address key domains outlined in a standard framework for evaluating acceptability, and a rigorous transcription process. This process involved thorough review and analysis of interview transcripts by at least two authors. The interviews took place within a six-week timeframe following the intervention, maximising participants' ability to recall their experiences accurately. However, there are some limitations. Of the 24 participants invited to provide qualitative feedback, four withdrew from the RCT, and were therefore uncontactable for the semi-structured interview for the current acceptability study. However, two of these four participants did provide unstructured feedback following withdrawal and their critical commentary is noted in the results and discussion. We did not examine whether participants’ responses differed according to their level of improvement on the primary outcome of the trial, potentially limiting our ability to explore how treatment effects influences acceptability. Moreover, the semi-structured interviews were conducted by someone familiar to the participants from the intervention (i.e., NN-N) which may have influenced participants willingness to share critical feedback. Nevertheless, all participants shared a range of both positive and negative feedback, including feedback about the therapists and therapeutic environment which reached a critical saturation point where no new themes arose (Braun & Clarke, 2021).

Conclusions and clinical implicationsWe evaluated the acceptability of iDBT-Pain, an intervention that demonstrated efficacy to improve emotion dysregulation, depression and pain intensity in a recent RCT for people with chronic pain (Norman-Nott et al., 2025). Feedback from participants was categorised as barriers or facilitators within the domains of a theoretical framework of acceptability (Sekhon, Cartwright & Francis, 2017). Response patterns demonstrated acceptability of an emotion regulation focused approach within a holistic treatment model for chronic pain, whilst highlighting the need that clinical assessment should evaluate participants readiness for an approach that centres on the emotional experience of chronic pain. Perspectives about a group-based approach demonstrated acceptance, and reinforced critical benefits in sharing experiences and validation whilst also indicating the necessity to evaluate an individual’s vulnerability to picking up on the emotionality of others in the group. Participant’s commentary indicated acceptance of an internet delivered approach including a dynamic blend of self-directed learning via digital and printed materials alongside guided online sessions, whilst highlighting the potential opportunities to improve personalisation. These findings have implications for developing iDBT-Pain and for other interventions focused on the emotional experience of chronic pain, particularly those that are delivered online and to groups. The iDBT-Pain intervention is currently being updated based on participant feedback, and these revisions will be further evaluated in future studies. This work will also allow exploration of how treatment response may relate to participants’ perceptions of acceptability. Our findings also highlight the potential importance of emotion regulation as a mechanism in chronic pain, contributing to the research championing deeper investigation into emotion regulation as a central psychological target in chronic pain mental health treatment.

Authors’ contributionsNN-N and SMG conceptualised the idea for this study. The methodology, analysis plan, interview guide and codebook were developed by NN-N, SMG, YQ, NH-S, and RRNR. Data collection was performed by NN-N, analysed by NN-N, SMG, YQ, NH-S, and RRNR, and critiqued by JHM, JSu, and JSh. NN-N drafted the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. Successive drafts received substantial contributions from all authors to revise and critically review all content. The final version of the manuscript was approved by all authors. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work, and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding statementThis work was supported by the Medical Research Future Fund (Grant ID: MRF2027056). SMG was supported by a Rebecca Cooper Fellowship from the Rebecca L. Cooper Medical Research Foundation. NN-N was supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship (administered by the University of New South Wales), a supplementary scholarship administered by Neuroscience Research Australia (NeuRA) and the PhD Pearl Award from NeuRA. NH-S was supported by a grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (ID2001653). RRNR was supported by the University of New South Wales School of Medical Sciences Postgraduate Research Scholarship and a NeuRA Ph.D. Candidature Supplementary Scholarship. The funding bodies had no role in the decision to publish this research.

Data availabilityThe qualitative data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Dr Jina Suh reports a relationship with Microsoft Research that includes: consulting or advisory. Prof Sylvia Gustin reports a relationship with Rebecca L Cooper Medical Research Foundation that includes: funding grants. Dr Rodrigo Rizzo reports a relationship with University of New South Wales School of Medical Sciences that includes: funding grants. Prof James McAuley reports a relationship with National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia that includes: funding grants. Prof James McAuley reports a relationship with Australian Government Medical Research Future Fund that includes: funding grants. Prof Sylvia Gustin reports a relationship with Australian Government Medical Research Future Fund that includes: funding grants. Dr Nell Norman-Nott reports a relationship with Australian Government Medical Research Future Fund that includes: employment and funding grants. Dr Negin Hesam-Shariati reports a relationship with National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia that includes: funding grants. Dr Nell Norman-Nott reports a relationship with Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship that includes: funding grants. All authors declare no other additional competing interests. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.