Frailty is a state of vulnerability characterised by a decrease in physiological reserve and the ability to respond to stress, which increases the risk of complications, adverse effects of treatments and functional decline. Assessing frailty allows the biological age of patients to be determined, beyond their chronological age, providing a more accurate picture of their health status and care needs. The proportion of older adults with IBD is increasing in parallel with the ageing of the general population, and it is estimated that in the next decade, more than a third of IBD patients will be over 60 years of age. This population may suffer from complications arising from previously developed IBD and is particularly susceptible to developing side effects from treatment, making comprehensive assessment essential in order to identify those who are most vulnerable. Frailty is compounded by other geriatric syndromes such as comorbidity and polypharmacy, which can significantly interfere with the management and course of IBD, influencing the therapeutic strategy and prognosis.

ObjectiveIn this context, comprehensive geriatric assessment should be systematic in elderly patients with IBD, with the aim of detecting functional deficits and implementing specific interventions for nutritional support, functional rehabilitation and psychological care to optimise their progress. This position paper aims to establish recommendations in this regard based on the available evidence.

ConclusionsThe systematic incorporation of comprehensive geriatric assessment in the management of older people with IBD represents an essential strategy for improving clinical outcomes, adapting treatments to the patient's functional capacity and promoting a truly person-centred approach.

La fragilidad es un estado de vulnerabilidad caracterizado por una disminución de la reserva fisiológica y la capacidad de respuesta ante el estrés, lo que aumenta el riesgo de complicaciones, efectos adversos a los tratamientos y deterioro funcional. La valoración de la fragilidad permite determinar la edad biológica de los pacientes, más allá de su edad cronológica, proporcionando una visión más precisa de su estado de salud y necesidades asistenciales. La proporción de adultos de edad avanzada con EII se halla en aumento de forma paralela al envejecimiento de la población general y se estima que, en la próxima década, más de un tercio de los pacientes con EII superarán los 60 años. Esta población puede sufrir las complicaciones derivadas de la propia EII desarrolladas previamente a la vez que es particularmente susceptible a desarrollar efectos secundarios del tratamiento, lo que hace imprescindible su evaluación integral con el fin de identificar aquellos más vulnerables. A la fragilidad se unen otros síndromes geriátricos como la comorbilidad y la polifarmacia que pueden interferir de forma notable con el manejo y el curso de la EII, condicionando la estrategia terapéutica y el pronóstico.

ObjetivoEn este contexto, la evaluación geriátrica integral debe ser sistemática en pacientes de edad avanzada con EII, con el objetivo de detectar déficits funcionales e implementar intervenciones específicas de apoyo nutricional, rehabilitación funcional y atención psicológica para optimizar su evolución. Este documento de posicionamiento pretende establecer recomendaciones al respecto basadas en la evidencia disponible.

ConclusionesLa incorporación sistemática de la valoración geriátrica integral en el manejo de personas mayores con EII representa una estrategia esencial para mejorar los resultados clínicos, adaptar los tratamientos a la capacidad funcional del paciente y favorecer un enfoque verdaderamente centrado en la persona.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) encompasses a group of chronic disorders including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), characterised by persistent and relapsing inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. These conditions not only have a negative impact on patients’ quality of life, but are also associated with long-term complications that may lead to disability.1,2 As IBD most often begins during adolescence or early adulthood, frailty constitutes a critical yet frequently underestimated aspect of the disease. Frailty is a condition characterised by reduced physiological reserve and diminished resilience to stressors, resulting in greater vulnerability and an increased risk of adverse outcomes. Frailty is a condition characterised by reduced physiological reserve and diminished resilience to stressors, resulting in greater vulnerability and an increased risk of adverse outcomes. It involves not only physical aspects, but also psychological and social dimensions.3 The rising prevalence of IBD, coupled with a mortality rate very similar to that of the general population, makes it increasingly urgent to understand and address frailty in these patients. The interaction of chronic inflammation, malnutrition, loss of muscle mass and other factors exacerbates frailty and, consequently, the risk of hospitalisation, surgical complications and mortality.4

Identifying and managing frailty in IBD is a clinical challenge and requires a multidimensional approach. This position paper aims to show the interrelationship between frailty and IBD, its prevalence, the main risk factors, its clinical implications in IBD and reviews available tools for its identification and potential intervention strategies.

Concept of frailty and its main determinantsAccording to the dictionary of the Royal Spanish Academy, fragile means "that which may deteriorate easily".5 In health terms, the most widely accepted definition among the many in existence is that developed in the field of geriatrics, which defines frailty as a biological syndrome of reduced reserve and resistance to stressors, resulting from the cumulative decline of multiple physiological systems, conferring increased vulnerability and risk of adverse outcomes.6,7 With ageing, a gradual decline in physiological reserve occurs; in frailty, this decline is accelerated and homeostatic mechanisms begin to fail.8 A frail person has a higher risk of disability and mortality following even minimal external stressors.

Frailty becomes more prevalent with ageing, although not all older people are frail.9 Conversely, frailty can occur at any age, particularly in individuals with chronic disease.8 The risk of frailty increases with chronological age, the presence of comorbidities, cognitive decline, sensory impairment (hearing and vision), polypharmacy, low physical activity, poor dietary intake, and low socioeconomic status, among other factors (Table 1).10 One critical factor that has received special attention in recent years is sarcopenia (loss of muscle mass), which leads to weakness and impaired muscle function, and is frequently associated with ageing.11

Risk factors associated with onset and progression of frailty.

| Sociodemographic | Clinicians | Lifestyle | Biologics |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Although often mistakenly used as synonyms in clinical practice, frailty, disability and comorbidity are distinct concepts. Comorbidity, defined as the coexistence of multiple diseases and medical conditions in the same individual, may contribute to the onset and progression of frailty (and vice versa). Disability is determined by any limitation or restriction in an individual’s activity or social participation due to a health condition. Frailty, however, may represent a precursor stage to disability and should be considered a dynamic process, as its severity may fluctuate and can even be reversible.12

Assessment of frailty makes it possible to distinguish between robust, pre-frail, frail, and disabled individuals. The prevalence of frailty in the population is often difficult to establish, because the available data are heterogeneous, both in terms of the methods used for assessment and the populations studied.11 The overall prevalence of frailty in Europe has been estimated at 18%, ranging from 12% in community-dwelling individuals to 45% in other settings. This variation reflects fluctuations in frailty during acute illness and the high level of chronic multimorbidity among institutionalised patients.13

Frailty is associated with a greater risk of adverse health outcomes, including falls, hospitalisation, institutionalisation, and mortality, as well as an exponential increase in healthcare costs.7 Although there is broad consensus regarding the theoretical concept of frailty, the complexity of its pathophysiology and the diversity of predisposing factors make it difficult to establish universal diagnostic criteria and a gold standard for its assessment10,11 (Fig. 1).

The detection and appropriate management of frailty lead to significant improvements in health outcomes for patients, potentially increasing independence and reducing the burden on caregivers and healthcare systems. Comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) is the reference tool for evaluating frailty.

CGA is a multidimensional diagnostic process, usually interdisciplinary, aimed at quantifying an individual’s medical, functional, psychological and social problems and capabilities, and enabling the design of a treatment and follow-up plan. Although it requires time and specialised training, CGA performed by a multidisciplinary team with expertise in geriatrics has been shown to improve health outcomes compared with the traditional medical approach.14

As it is not feasible to carry out a CGA for all older adults, frailty screening enables the detection of those at high risk who should be referred for a full CGA. The most widely known and used methods for screening and evaluating frailty in older adults are the Fried phenotype7 and frailty indices, both of which provide crucial information about frailty status and have particular advantages depending on the evaluation context.15,16

The Fried phenotype defines frailty as a clinical syndrome with specific criteria, based on the presence of five physical characteristics.7 A person is considered frail if three or more of the following criteria are met:

- 1

Unintentional weight loss: specifically, loss of more than 4.5 kg or 5% of body weight in the past year.

- 2

Muscle weakness: measured by handgrip strength, adjusted for sex and body mass. Frailty is defined when strength falls within the lowest quintile.

- 3

Slowness in the lowest quintile indicates frailty. Slowness in the lowest quintile indicates frailty.

- 4

Self-reported fatigue or exhaustion: individuals report a persistent sensation of tiredness or exhaustion.

- 5

Low physical activity: measured by weekly energy expenditure in physical activities; as with the other parameters, being in the lowest quintile according to sex indicates frailty.

The Fried phenotype is useful because it identifies individuals at an early stage who are at higher risk of adverse health outcomes, such as disability, hospitalisation, falls and mortality.7

Mathematical frailty indices, also known as deficit accumulation models, provide a different perspective for evaluating and quantifying frailty in older people. This approach, popularised by Rockwood and Mitnitski,17 measures frailty as an index that summarises the number of health problems or deficits a person has accumulated.

One of the most widely used and evidence-based indices is the Frail-CGA Index (IF-VIG). This tool was specifically designed to identify and classify the degree of frailty in older adults. It encompasses different domains, including functional, nutritional, cognitive, emotional and social aspects, as well as geriatric syndromes, severe symptoms and chronic diseases. The FI-VIG stands out for its practicality and efficiency, allowing a rapid assessment of frailty through 22 questions covering 25 deficits. These range from difficulties with instrumental activities of daily living (such as managing money or medication) to specific clinical conditions (such as malnutrition, cognitive impairment, depression, insomnia or social vulnerability). It also considers the presence of geriatric syndromes, such as falls or pressure ulcers, polypharmacy, and chronic diseases affecting different organs or systems. The IF-VIG provides a score that reflects the degree of frailty and complements the Fried phenotype. While the Fried phenotype identifies frailty on the basis of specific physical features, the FI-VIG offers a broader and more detailed perspective incorporating clinical, functional and social aspects, thus enabling a more comprehensive assessment of an individual’s condition. The IF-VIG is particularly useful in clinical settings where rapid and efficient frailty screening is required to support decision-making.18 A publicly accessible calculator is available via the website of the Chronicity Research Group of Central Catalonia (C3RG): https://es.c3rg.com/index-fragil-vig.

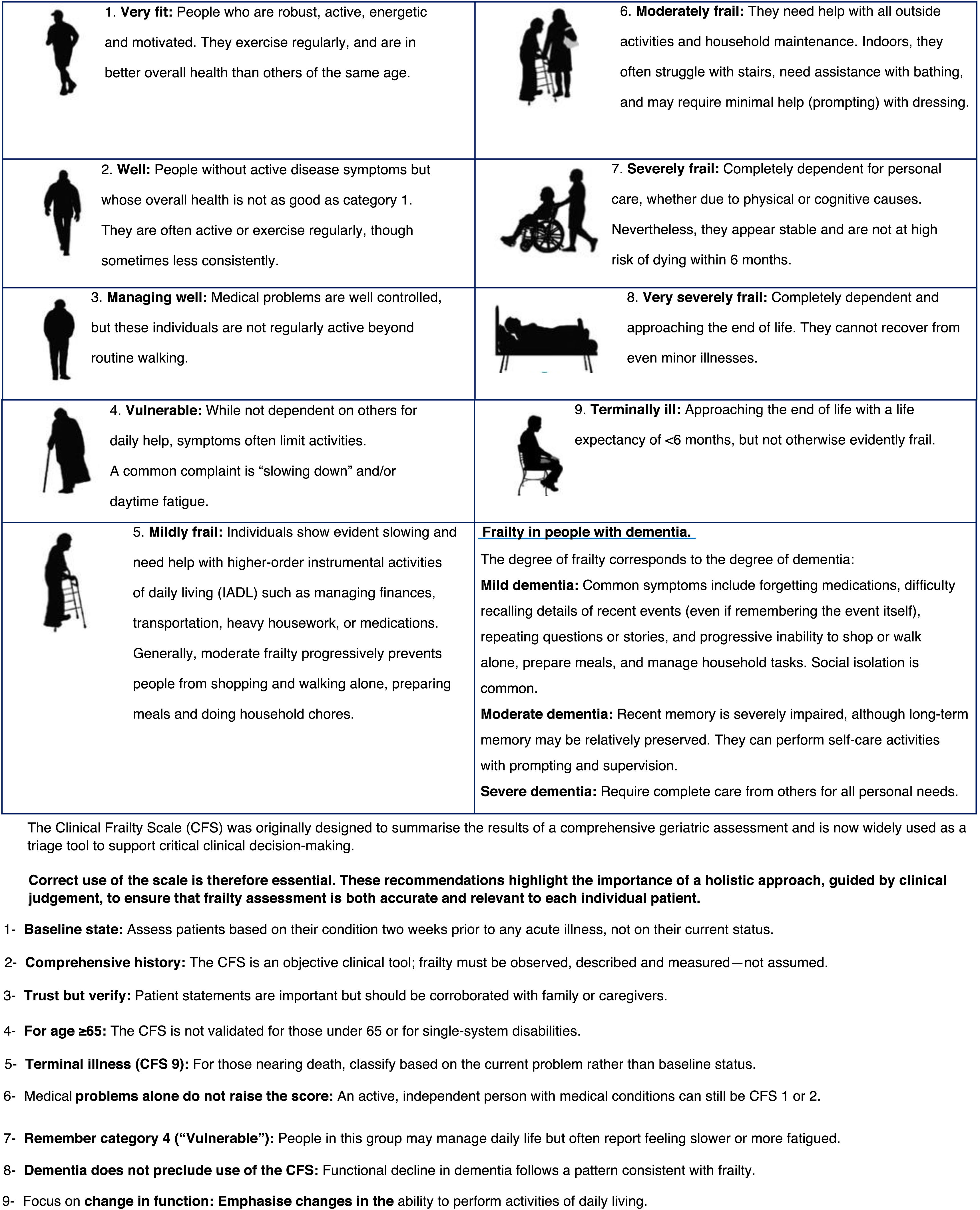

The Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) is another tool developed to assess frailty in older adults, originally designed by Rockwood et al.19 Unlike the IF-VIG, the CFS provides a qualitative and more visual measure of frailty using a simple visual scale based on clinical observation and judgement (Fig. 2). It classifies frailty into nine categories, each illustrated with images and detailed descriptions of activity level, independence, and health status. The CFS is widely used in clinical settings to quickly evaluate frailty, which is especially helpful in acute care situations for supporting clinical decisions. Its intuitive format makes it easy to use by healthcare professionals without the need for extensive training. However, the CFS may be subjective, depending on the assessor’s interpretation, and may not detect subtle changes in frailty status. The CFS is also available as a mobile application: https://www.scfn.org.uk/cfs-app.20

The most recent population-based studies have reported an increase in the incidence of IBD in developing countries and a rising global prevalence, with the highest rates observed in North America and Europe (prevalence 0.3%).21,22 This phenomenon is likely multifactorial, with contributing factors including exposure to environmental influences such as a Western diet and pollution,23 as well as the global increase in life expectancy.24

Approximately 25–30% of patients with IBD are over 60 years old, a proportion expected to increase further given population ageing and the rising incidence of IBD in this age group.25–30 Several studies have shown that the incidence of IBD among individuals aged >60 years accounts for 10–20% of incident cases, making this the subgroup with the sharpest increase over recent decades. Unlike in younger populations, incidence rates do not decline with age, particularly in regions with a high socioeconomic status.27,31–40 In addition, improvements in diagnostic techniques and greater awareness of IBD may have reduced the rate of undiagnosed cases in this population.23

In clinical practice, two distinct subgroups of older patients with IBD can be identified: those diagnosed at a younger age and ageing with long-standing disease, and those diagnosed at an older age (referred to as late-onset IBD). Although all patients diagnosed over the age of 40 fall into the A3 group of the Montreal classification (for CD), it is recognised that late-onset IBD presents with distinct phenotypic features, including a more indolent course and a higher risk of drug-related toxicity.23,24

Some studies indicate a higher proportion of UC compared with CD among older patients (ratio 4:1.5).36,39 Compared with IBD diagnosed earlier in adulthood, late-onset disease tends to show a predominance of colonic location, a lower tendency towards penetrating disease, reduced rates of perianal involvement in CD, and a predominance of distal disease in UC.39,41–43 These differential characteristics are summarised in Table 2.

Differences between patients diagnosed with late-onset inflammatory bowel disease compared to young adults.

| >60 years | 16−40 years | |

|---|---|---|

| Extension |

|

|

| CD pattern |

|

|

| Hospital admission |

|

|

| Infections |

|

|

| Cancer |

|

|

UC: ulcerative colitis; CD: Crohn's disease; NHL: non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

A systematic review comparing the course of IBD in patients diagnosed at <60 years versus >60 years found similar rates of corticosteroid use. However, the use of immunosuppressants and biologics was lower in older patients.43 Although a milder disease course has traditionally been described in this population, rates of surgery and hospitalisation tend to be higher. This, together with the lower use of advanced therapies, may reflect a more conservative therapeutic approach.

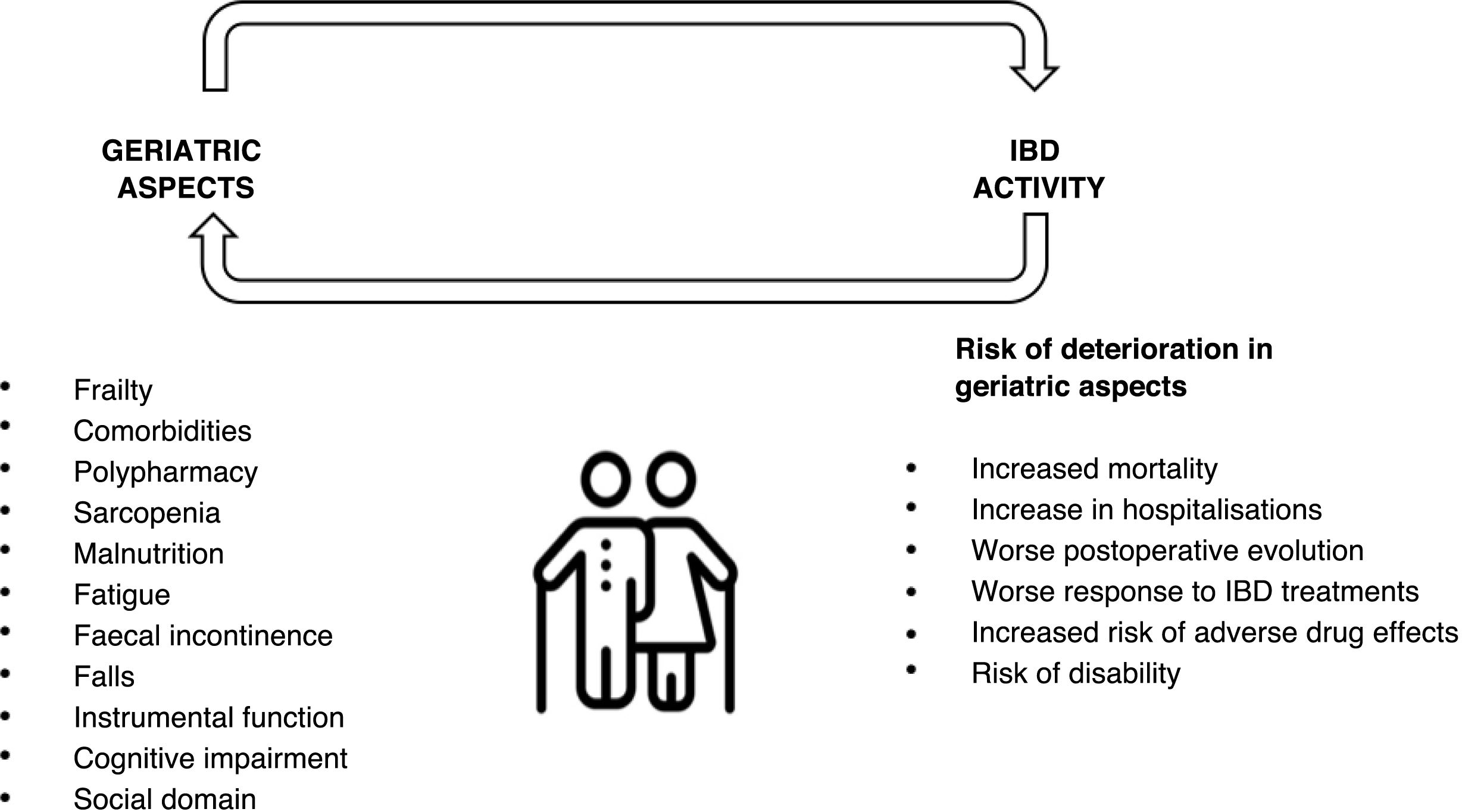

Frailty and its assessment in inflammatory bowel diseaseOlder patients with IBD show higher rates of comorbidity and polypharmacy, and therefore at increased risk of adverse events. In addition, patients with IBD develop geriatric syndromes, such as osteoporosis, hip fractures, infections and malignancies, and have an increased risk of cognitive and psychomotor disorders at younger ages44–49 (Fig. 3). Moreover, frailty has been observed at earlier ages in patients with IBD, probably related to the chronic inflammatory burden of the disease.50 However, the causal relationship between IBD and frailty remains debated. While some studies suggest a frail phenotype may predispose to the development of IBD,51 others have reported that IBD activity contributes to frailty and accelerates its onset.52

In a cohort of 11,001 patients with IBD across all ages, Kochar et al. reported that frailty prevalence increased with age, rising from 4% among patients aged 20–29 years to 25% among those aged >90 years.53 A recent meta-analysis, including nine studies with 1,495,695 patients, estimated frailty prevalence at approximately 18% in patients with IBD.54

Initial studies assessing frailty in IBD were conducted in surgical settings and demonstrated that frailer patients experienced higher morbidity and mortality and a greater likelihood of reintervention.55–57 The association between frailty and infection risk remains controversial: some studies report a higher risk of infections related to anti-TNF or immunosuppressive therapy,57 while others have found no increase in serious infections, or only an association with certain treatments such as vedolizumab.58 Frail patients with IBD have also been shown to have a higher risk of hospitalisation and reduced quality of life and functional status.57,59

A recent Italian prospective study suggested the only factor associated with frailty was IBD activity.60 The same group also showed that improvement in frailty phenotype correlated directly with the use of biologics and inversely with persistent clinical activity.52 This observation had previously been reported in a retrospective US study of 1210 patients with IBD initiating anti-TNF therapy,61 reinforcing the concept of frailty as a dynamic state influenced by IBD activity.

Frailty indices in IBDAs a result of the lack of a widely accepted definition of frailty and of specific, validated frailty indices in patients with IBD, the available studies have used different indices and different cut-off points to assess the degree of frailty. Most available studies, largely retrospective, have employed indices based on diagnostic codes (ICD) extracted from medical records. The main frailty indices and their cut-offs are summarised in Table 3. Beyond these indices, comprehensive geriatric assessment can provide valuable insight into functional status and frailty in patients with IBD.7,62 In a recent study, 40% of IBD patients over 65 years presented moderate deficits on geriatric assessment.63

Recommendations:

- •

In older patients with IBD or in those with active disease, we recommend regular frailty assessment and suggest the use of simple tools such as the Clinical Frailty Scale.

- •

In patients with IBD and frailty, we recommend prioritising control of IBD activity as a means of improving frailty status.

Frailty indices used in the different IBD studies.

| Author, year | Frailty index | Definition of frail patient |

|---|---|---|

| Cohan et al55, 2015 | “Frailty trait count” | Presence of ≥1 of the 6 variables |

| Telemi et al.56, 2018 | Modified Frailty Index | Score ≥ 1 |

| Kochar et al.57, 2020 | Adapted Hospital Frailty Risk Score 181 | ≥1 ICD-9 code related to frailty |

| Qian et al.205, 2021 | Hospital Frailty Risk Score | Score > 5 |

| Faye et al.206, 2021 | Fragility by groups | ≥1 ICD-9-CM code |

| Singh et al.58, 2021 | Hospital Frailty Risk Score | Score > 5 |

| Kochar et al.61, 2022 | Claims-based frailty index | Score in the highest quartile in the pre- or post-treatment period |

| Kochar et al.207, 2022 | Hospital Frailty Risk Score | 0−5 low risk of frailty |

| Score > 5 high risk of frailty | ||

| Salvatori et al.52,60, 2022−23 | Fried frailty phenotype | Score€≥ 3 |

| You et al.208, 2023 | Frail Scale validated in Chinese | Score ≥ 3 |

| Rozich et al.209, 2023 | Modified Frailty Index | Score€≥ 2 |

| Zhang et al.51, 2023 | Fried frailty phenotype | Score€≥ 3 |

| Bedard et al.210, 2023 | Clinical Frailty Scale | Score€≥ 4 |

| Wang et al.135, 2022 | Frailty Index | Not specified |

| Asscher et al.59, 2024 | G8 Questionnaire | Frailty risk ≤ 14 |

Managing IBD in older adults presents unique challenges. This population is more susceptible to drug-related adverse events, necessitating closer monitoring and careful risk–benefit assessment before treatment initiation.61 The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of medications may be altered in elderly patients due to physiological changes associated with ageing, so dose64 adjustment may be necessary, which could influence therapeutic efficacy. On the other hand, we have little data on the impact of frailty or comorbidities on the efficacy and safety of different drugs. in part because most clinical trials exclude patients with common comorbidities seen in older adults.65 These factors may lead to less ambitious treatment targets, which can, in turn, influence the trajectory of frailty and its consequences.

AminosalicylatesThey are a good therapeutic alternative for the treatment of UC due to their effectiveness and excellent safety profile, making them the most widely used treatment in elderly patients with UC. In the TARGET-IBD cohort (∼3000 patients), older adults received more aminosalicylates and fewer anti-TNF agents than youngerpatients.66 Cardiovascular disease and diabetes,68—but not age per se,67—may increase the risk of aminosalicylate-related nephrotoxicity. Another aspect to consider in elderly patients is that topical administration of aminosalicylates may be more difficult due to the patient's functional status and the higher prevalence of faecal incontinence.69,70

CorticosteroidsCorticosteroids remain commonly used in IBD, though practice is shifting towards limiting exposure because of frequent adverse effects, especially with prolonged or repeated courses. In elderly patients with IBD, the use of systemic corticosteroids is common, with some series reporting their use as maintenance therapy (treatment with prednisone for more than 6 months) in up to one-third of this population.71 This reflects a misplaced perception that steroids are safer than advanced therapies,72 despite high rates of serious infections in older adults and with courses exceeding 45 days.73 In terms of safety, it is important to bear in mind that both age (particularly in women) and corticosteroid therapy are established risk factors for osteoporosis in IBD,74 Prevention (calcium/vitamin D) and early diagnosis are essential to avert osteoporotic fractures.75

ThiopurinesDespite the fact that elderly patients have been excluded from clinical trials with immunosuppressants and biologics in IBD, there are numerous studies in clinical practice that suggest that the efficacy of thiopurine treatment is not inferior in this population.76,77 However, adverse effects are more common and often limit use in frail patients. In the EPIMAD registry, 10-year cumulative adverse event probabilities with immunosuppressants were 27% in CD and 15% in UC.35 In a study derived from the ENEIDA registry, it was found that patients over 60 years of age who started thiopurine treatment were more likely to develop myelotoxicity and hepatotoxicity, which led to lower treatment persistence.78 Older adults also face an increased risk of lymphoproliferative disorders79 and other malignancies (urinary tract, skin).80–82

BiologicsAnti-TNF agentsEarly reports suggested reduced efficacy in older adults,83 but subsequent longer-term data indicate age is not a determinant of efficacy. An indirect comparison of anti-TNF RCTs in UC found no relationship between age and response, but a greater likelihood of adverse events in older adults.84 Pharmacokinetic differences and age-related factors may contribute to slower short-term responses,23 while higher adverse-event rates in frail patients frequently prompt discontinuation (a bias when judging efficacy). However, the occurrence of adverse effects associated with anti-TNF agents is more frequent in the frail population and often forces their withdrawal, which is a bias to be taken into account in the assessment of efficacy. De Jong et al. analysed a cohort of 895 IBD patients and found that starting anti-TNF therapy at an older age – which usually means later treatment initiation – was associated with a higher likelihood of treatment failure.85 However, when the reason for treatment discontinuation was taken into account, this association was attenuated, particularly when distinguishing between cases where the drug was stopped due to lack of efficacy and those discontinued because of adverse events.

With respect to safety, anti-TNF therapy has been linked to an increased incidence of infections and malignancies in patients over 65 years of age and in those with comorbidities, compared with younger patients and even with older adults who have not been exposed to anti-TNF agents.86,87

Therefore, as with thiopurines, anti-TNF agents are as effective in older adults as in younger patients, but their safety profile necessitates an individualised approach to their use.88

VedolizumabVedolizumab, an anti-integrin with selective action at the splanchnic level, has shown a favourable safety profile in the treatment of IBD both in clinical trials and in real-world practice.89 It has been suggested that the use of more selective immunosuppressants, or agents with less ubiquitous targets, may confer particular advantages in frail patients. However, studies assessing the safety of biologics in older adults have yielded mixed results, with most reporting no significant differences in infection rates between the various biologics used in IBD in this population.89,90 A cohort study directly comparing infection rates between vedolizumab and anti-TNF therapy in patients with CD over 60 years of age found no significant differences after one year of treatment.91 Nevertheless, these studies are subject to selection bias, given the tendency to prescribe vedolizumab preferentially to more frail patients, which may have influenced the findings.

Despite these limitations, given vedolizumab’s favourable safety profile in the general population and the increased susceptibility of older adults to adverse events associated with anti-TNF agents, expert recommendations continue to prioritise its use in this population.92

Anti-IL-12 and IL-23 inhibitorsSimilar to vedolizumab, the favourable safety profile of these drugs has supported their theoretical positioning earlier in the treatment pathway for frail IBD patients. No differences have been observed in rates of serious infection or treatment discontinuation due to adverse events in older adults.93 The efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in CD have been evaluated in multiple large cohorts, with no differences reported in treatment response or persistence between older and younger patients.94,95

By contrast, data on risankizumab in older adults remain very limited owing to its recent approval for IBD. By contrast, data on risankizumab in older adults remain very limited owing to its recent approval for IBD. Unlike other drugs, pivotal trials permitted the inclusion of older patients, although the mean age did not exceed 40 years, precluding robust subgroup analyses by age.96–98 However, safety data from psoriasis suggest no increase in adverse events among older adults.99 With the same mechanism of action and thus a similar safety profile, mirikizumab is already available and guselkumab is expected to be approved for IBD in the near future.

JAK inhibitorsEvidence on the efficacy of these drugs in older adults with IBD is modest. In the pivotal trials of tofacitinib and filgotinib, few older patients were included, but efficacy appeared comparable with that observed in younger populations.100,101 Nonetheless, caution is required as adverse events such as infections, major cardiovascular events and thromboembolic phenomena occur more frequently in older patients.102 In addition, another aspect to consider with the use of these drugs in elderly patients is their renal metabolism (and also hepatic metabolism in the case of tofacitinib), which necessitates dose adjustments in renal or hepatic impairment and increases the risk of drug–drug interactions, a particular concern in the context of polypharmacy.99

For tofacitinib, the increased risk of major cardiovascular events observed in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in clinical trials—particularly in those ≥65 years—led the European Medicines Agency to issue a safety warning restricting its use in older adults or those with cardiovascular risk factors to situations where no alternative therapy is available.103,104 However, in subsequent long-term safety studies and again in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, no increased risk of cardiovascular events was found in elderly patients at a dose of 5 mg every 12 h.105 A recent meta-analysis of clinical trials similarly reported no increased cardiovascular risk with tofacitinib or upadacitinib compared with placebo or other biologics.106

Regarding thromboembolic risk, post-marketing studies from the US Food and Drug Administration suggest that incidence may be higher with tofacitinib than with other, more selective JAK inhibitors such as upadacitinib or filgotinib in patients over 65 years.107,108

Another key concern in older adults is infection risk, particularly herpes zoster. This infection is associated with increased morbidity due to post-herpetic neuralgia and the potential for polypharmacy linked to long-term analgesic use.109 Preventive measures recommended for patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy must therefore be implemented, with particular emphasis on herpes zoster vaccination in older adults.110

Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) receptor modulatorsS1P modulators (ozanimod, etrasimod) are an emerging option for UC, acting by modulating lymphocyte egress from lymph nodes. These agents act by modulating lymphocyte migration from the lymph nodes.111,112 However, evidence regarding their efficacy and safety in older or frail patients is very limited. Before initiating S1P inhibitors in older or frail patients with IBD, several factors must be carefully considered to minimise risk. These drugs may cause transient bradycardia and cardiac conduction abnormalities; therefore, baseline electrocardiography is recommended, together with cardiology assessment in patients with a history of cardiovascular disease. Owing to their mechanism of action, S1P modulators increase the risk of opportunistic infections. It is therefore essential to assess vaccination status, with particular attention to varicella, pneumococcal and COVID-19 immunisation, and to exclude latent tuberculosis and other chronic infections prior to treatment initiation, as with other biologics.113 Liver function should be monitored before and during treatment. Ophthalmological evaluation is advised in patients with diabetes and/or uveitis, who are at higher risk of developing papilloedema. In addition, a decline in renal function has been reported in some cases, warranting periodic monitoring of renal parameters.

In conclusion, the use of S1P modulators in frail or older patients requires thorough baseline assessment and close follow-up to minimise complications.

Other therapiesGranulocyte/monocyte adsorption apheresis (GMA) is a non-pharmacological technique in which blood is circulated extracorporeally through a column of microbeads that selectively remove activated granulocytes and monocytes, thereby reducing intestinal inflammation. In older or frail patients—where immunosuppressant and steroid toxicities are of particular concern—GMA can be a safe option to control inflammation without substantially increasing the risk of infection or malignancy This strategy allows inflammation to be controlled without significantly increasing the risk of infections or neoplasms. Data suggest GMA can induce clinical remission in a considerable proportion of older patients with moderate–severe UC, with a favourable safety profile and no serious adverse events, even in the context of multimorbidity.114

Treatment in IBD patients with specific comorbiditiesAs noted, comorbidity is frequently an exclusion criterion in clinical trials, limiting the available evidence in certain scenarios. A history of malignancy—regardless of age—must be considered when selecting immunosuppressive therapy. An ENEIDA study evaluated the safety of initiating immunosuppressants (thiopurines and/or anti-TNF agents) in patients with history of cancer,115 finding no increased risk of recurrence or new cancer when therapy was started at least two years after completion of oncological treatment. These findings were reinforced by the prospective SAPPHIRE study, which included IBD patients with prior cancer and found no significant increase in incident malignancy following exposure to immunosuppressants, including biologics and small molecules. This evidence supports the safe use of these therapies in carefully selected patients.116 Moreover, newer, more selective agents may offer an even safer alternative in this setting, and current clinical guidelines recommend their use over thiopurines and anti-TNF therapy.117

SurgeryAlthough frail patients are generally considered poorer candidates for surgery due to associated morbidity, available data indicate higher surgical rates (both in UC and CD) among older patients, particularly soon after diagnosis,41,118 suggesting possible underuse of appropriate medical therapy.

Frail surgical candidates should undergo optimal preoperative preparation to minimise the risk of postoperative complications,119 including nutritional assessment and optimisation, and avoidance of corticosteroids.120 Unfortunately, no specific perioperative protocols exist for IBD patients. A recent systematic review highlighted the lack of evidence regarding the implementation of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) pathways in this population,121 despite their proven benefits in colorectal surgery.

Recommendations:

- •

Functional limitations and possible faecal incontinence should be considered in older patients when prescribing topical therapies, with attention to family and caregiver support.

- •

Systemic corticosteroids should be avoided whenever possible in older or frail patients, with early diagnosis and preventive measures for osteoporosis prioritised.

- •

Thiopurines and anti-TNF agents should be replaced by safer therapeutic alternatives in older patients, owing to their higher carcinogenic potential.

- •

Vedolizumab and IL-23 or IL-12/23 pathway blockers should be prioritised in older or frail patients with an indication for advanced therapies.

- •

JAK inhibitors should be used cautiously in older or frail patients, given their higher risk of infections, major cardiovascular events and thromboembolism.

- •

Preventive measures routinely recommended for patients receiving biologics and immunosuppressants should be implemented, with herpes zoster vaccination prioritised in older adults.

- •

In frail IBD patients undergoing surgery, preoperative optimisation should include nutritional assessment and supplementation and avoidance of corticosteroids; systematic implementation of ERAS protocols is advisable.

- •

In frail IBD patients undergoing surgery, preoperative optimisation should include nutritional assessment and supplementation and avoidance of corticosteroids; systematic implementation of ERAS protocols is advisable.

Nutrition in the frail patient with inflammatory bowel disease Nutrition in IBD patients is a crucial aspect of care, with particular nuances in those who are frail. The prevalence of malnutrition is higher in older adults and rises further in the presence of frailty due to the combination of multiple factors.122 Advanced age itself is associated with physiological changes in body composition as a consequence of ageing.123 In addition, comorbidities are common (diabetes, pulmonary, renal, hepatic, cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease, and neurological disorders) and patients are often exposed to repeated hospital admissions. Other frequent contributing factors include loss of appetite or dietary modification due to difficulties with chewing.124,125 Neuropsychiatric conditions (depression, anxiety, cognitive decline)126 and social circumstances (loneliness, isolation, inability to shop or cook, and, at the extreme, dependency) may also contribute to weight loss and malnutrition, even in the absence of underlying organic disease. In frail or older patients with IBD, these factors are further compounded by the digestive disease itself, although individual scenarios vary widely depending on disease-related factors such as location, activity, and history of surgery. The interaction between inflammation, comorbidity and frailty largely determines the nutritional status. Correcting malnutrition in a frail patient can improve frailty—particularly its physical domain—and thereby indirectly minimise the risks of certain IBD therapies and optimise health outcomes.

Diagnostic assessment of nutritional status in the frail patientNutritional assessment should be undertaken in all IBD patients, and is especially important in the older or frail population. This may then be supplemented by a more detailed evaluation, including body composition analysis. Screening tools for malnutrition (and even diagnostic criteria) largely rely on relatively crude clinical measures such as body mass index (BMI) and weight loss. In health, BMI correlates well with body composition and is widely used for classification and even prognosis. However, this correlation is weakened in the context of disease. In older adults and in patients with chronic conditions, the so-called “obesity paradox” may occur, where higher BMI values are associated with better outcomes. Conversely, in disease-related malnutrition, the relationship between BMI and fat or lean mass becomes nonlinear, making it difficult to estimate lean and muscle mass from BMI alone.127 At a minimum, nutritional assessment should include physical examination (anthropometry), targeted clinical history (dietary intake), blood tests with nutritional (pre-albumin) and vitamin parameters, and, ideally, complementary tests to objectively assess body composition.127 Useful techniques in this regard include bioelectrical impedance, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), with ultrasound also emerging as a promising tool (Table 4).

Practical body composition assessment tools.

| Allows or relies on… | Advantages | Disadvantages | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometry | Physical examination. Various formulas proposed | Simplicity, minimum cost, available | Time-consuming, not very reproducible | Allows easy monitoring |

| Electrical bioimpedance | Different resistance of tissues to the passage of an electric current | Simple, minimal apparatus, non-invasive, inexpensive | In malnourished states, because of the dependence on regression equations and the patient's health status, individual (body composition) estimates are less accurate | Growing interest in the nutritional diagnostic value of crude electrical parameters (and vector analysis), independent of regression equations |

| Bone density scan (DEXA) | Radiation absorption differs from tissue to tissue. | Accurate and fast, no post-processing necessary. Direct assessment | Need for specific equipment and software (low availability) | Analyses the amount of fat, bone and lean mass, together and by anatomical area |

| CT | Radiation absorption by thresholds (Hounsfield units) | Possibility of use on scanning carried out for another reason ("opportunistic") | Radiation | Gold standard |

| Direct assessment | Various potential parameters (SMA, SMI, PMI) | |||

| MRI | Similar to CT (different units) | Possibility of use on a scan performed for another reason. Direct assessment. No radiation | Availability | Similar to CT |

| Nutritional ultrasound | Measurement of various areas | Availability. No radiation, simplicity | Non-standardised |

PMI: psoas muscle index, defined as the sum of the cross-sectional areas of the iliopsoas muscle at the L3 level divided by height squared; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; TMA: total muscle area; TMI: total muscle area indexed to height squared; CT: computed tomography.

Note: it is also possible to calculate total fat area, visceral fat area and intramuscular fat (by CT using segmentation based on Hounsfield units). In fact, L3 is chosen because it is the area that best represents these 3 compartments globally).

Nutritional management in frail IBD patients—more so than in other IBD populations—must be multidisciplinary, involving nutrition specialists and other healthcare professionals. Following assessment, individualised objectives and strategies should be defined. Available interventions include dietary modification, nutritional supplementation and, where possible, exercise. Disease activity is a major contributor to malnutrition and must always be considered, with appropriate treatment indicated.

Diet in frail patients with inflammatory bowel diseaseDietary interventions in IBD have received increasing attention, supported by higher-quality studies, although interpretation remains challenging. In frail IBD patients, however, specific evidence is lacking. The main objective is to restore nutritional status to improve frailty. Various diets have been studied as potential therapeutic strategies in IBD, with the Mediterranean diet gaining particular prominence, at least due to its additional general health benefits. In frail patients, dietary recommendations must take into account both nutritional status and the individual’s IBD and comorbidities. General energy requirements are 30–35 kcal/kg/day, using corrected weight in cases of extreme BMI. Daily protein intake should be 1 g/kg/day in patients with IBD in remission, and 1.2–1.5 g/kg/day during active disease.128 Specific deficiencies such as iron deficiency, vitamin B12 or folate should also be corrected. As a “baseline diet” for frail IBD patients, we suggest the Mediterranean diet, with individual modifications as required. Adaptations may include altering food texture or replacing protein sources with alternatives of higher biological value. Importantly, patient preferences must be considered; otherwise, adherence will be poor and recommendations ineffective.

Nutritional supplements in frail patients with inflammatory bowel diseaseNutritional supplements may be required when malnutrition is established (full Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition [GLIM] criteria), when there is risk of malnutrition (incomplete GLIM criteria or positive malnutrition screening without full GLIM criteria), and when dietary measures alone (increasing caloric/protein intake, palatability, or digestibility) are insufficient.129 Recommended oral supplements are polymeric, typically high-calorie and high-protein, so that 1–2 daily servings can provide significant nutritional benefit without reducing normal food intake. During active disease, supplements with qualitative and quantitative fat modifications (long-chain triglyceride restriction and <20 g fat per 1000 kcal) may offer advantages, but no differences have been observed in quiescent phases. Leucine-enriched supplements may confer greater ergogenic effects (particularly in sarcopenic frail patients), while omega-3-enriched formulations may enhance anti-inflammatory modulation. However, both may be less palatable, potentially reducing adherence and therefore clinical benefit.130

Physical activityExercise or physical activity, adapted to the individual’s actual capacity, is highly beneficial. Although often overlooked, when used appropriately it exerts positive effects on nutritional status through several mechanisms. Specifically, it improves sarcopenia, stimulates appetite, and contributes additional benefits for overall health. Recent studies suggest adequate protein intake helps prevent loss of muscle mass and may break the vicious cycle of malnutrition and frailty.130 Physical activity should therefore be regarded as an important complement to diet.

Recommendations:

- •

We recommend assessing nutritional status by means of physical examination, dietary intake assessment, and measurement of nutritional (pre-albumin) and vitamin parameters.

- •

We recommend prioritising the Mediterranean diet in patients with IBD, due to its additional health benefits.

- •

We recommend adjusting energy requirements to 30–35 kcal/kg/day, ensuring adequate protein intake with 1 g/kg/day during remission and 1.2–1.5 g/kg/day in active disease, and correcting specific nutritional deficiencies.

- •

We recommend the use of oral polymeric nutritional supplements, high-calorie and high-protein, 1–2 daily, without replacing regular dietary intake.

The term sarcopenia derives from the Greek for “poverty of flesh” and was first coined in 1989 to describe muscle loss. Initially lacking a formal definition or diagnostic criteria, it has since been established as a distinct entity (ICD code M62).131,132 Sarcopenia is defined as a progressive and generalised disorder of skeletal muscle characterised by a marked reduction in muscle mass, accompanied by loss of strength and physical performance.

The prevalence of sarcopenia in IBD appears to be higher than in the general population. According to a recent systematic review, one third of adult IBD patients would have myopenia and presarcopenia and almost one fifth would have sarcopenia.133 In frail or older IBD patients, the prevalence is presumed to be even greater. In general, sarcopenia is associated with loss of autonomy, higher risk of falls and fractures, hospitalisation and even mortality, with the consequent increase in healthcare costs. Among frail patients or those with comorbidities, these negative consequences are magnified, increasing overall vulnerability.134,135 Importantly, sarcopenia has also been associated with higher relapse rates and lower remission rates in patients with IBD, irrespective of age or frailty.136,137 Other studies suggest that the risks or effectiveness of certain therapies, including immunomodulators and biologics, may be independently modified by the presence of sarcopenia.138 In addition, sarcopenia has been linked to increased postoperative complications. While the precise mechanisms remain unclear, it is noteworthy that skeletal muscle appears to play roles in inflammatory regulation and possibly in immune function.139

Pathophysiology of sarcopenia in the general population and in inflammatory bowel diseaseMuscle mass is maintained through a regulated balance between protein synthesis and degradation, and disruption of this balance leads to sarcopenia. Based on causative factors, sarcopenia is classified as primary (age-related) or secondary (associated with chronic inflammatory, neoplastic, or neurological diseases, or with inactivity and malnutrition). Primary sarcopenia is a physiological manifestation of ageing, with an estimated 1–2% annual decline in muscle mass from the age of 50. Secondary sarcopenia associated with inflammatory disease may result from several mechanisms. The first, and likely most relevant, is the release of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and interleukin-6 (IL-6), which exert catabolic effects on muscle. The second is reduced levels of IGF-1, leading to protein catabolism, which can be reversed by some treatments such as anti-TNF agents.140,141 The third is malnutrition. Although malnutrition has been associated with sarcopenia in cohort studies in older populations,142,143 findings in IBD are more heterogeneous, suggesting a more complex interplay. In a study of 88 patients with CD, 21% were malnourished while almost 33% were overweight. Most patients with myopenia had either a normal BMI or were overweight/obese (49% and 16%, respectively),144 findings that were replicated in another similar cohort.145 Thus, BMI correlates only moderately with skeletal muscle mass, and many patients with sarcopenia may have a normal BMI.

Diagnostic assessment of sarcopenia in inflammatory bowel diseaseEarly identification of sarcopenia is essential for effective intervention. Screening can be undertaken using tools such as the simple, self-reported SARC-F questionnaire, which assesses difficulty in performing four functional activities (Table 5). Scores range from 0 to 10, with ≥4 suggesting sarcopenia. Inability to lift 4.5 kg, climb a flight of 10 stairs, cross a room, or rise from a chair strongly suggests severe sarcopenia. While relatively specific, the tool has low sensitivity.146

Sarcopenia screening test SARC-F.

| Component | Question/item | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Strength | How difficult is it to lift and carry 4.5 kg? | No difficulty = 0 |

| Some difficulty = 1 | ||

| A lot or unable = 2 | ||

| Assistance for walking | How difficult is it to walk across a room? | No difficulty = 0 |

| Some difficulty = 1 | ||

| A lot or unable without assistance = 2 | ||

| Getting up from a chair | How difficult is it to get up from a chair or bed? | No difficulty = 0 |

| Some difficulty = 1 | ||

| A lot or unable without assistance = 2 | ||

| Climbing stairs | How difficult is it to climb 10 stairs? | No difficulty = 0 |

| Some difficulty = 1 | ||

| A lot or unable = 2 | ||

| Falls | How many times has it fallen in the last year? | None = 0 |

| 1−3 = 1 | ||

| ≥ 4 = 2 |

Following screening, comprehensive evaluation is recommended, focusing on confirmation, severity and functional impact. This can be undertaken in three domains, using simple or more advanced tools:

- •

Muscle strength: – the leading indicator. Commonly assessed by handgrip strength using a dynamometer, due to its simplicity and moderate correlation with strength in other muscle groups. An alternative is the “chair stand test”, measuring time to stand five times from a chair without using the arms, or the number of repetitions in 30 s.

- •

Assessment of muscle mass: can be assessed directly by CT, MRI or DEXA, or indirectly by bioelectrical impedance analysis or other techniques. Muscle mass – can be measured directly by CT, MRI or DEXA, or indirectly using bioelectrical impedance analysis. Given the frequency of abdominal CT/MRI in IBD, these images may be repurposed to assess muscle mass, typically at the L3 vertebral level.

- •

Physical performance– integrates muscular, cardiorespiratory and neurological function. Gait speed is a simple and predictive measure of adverse outcomes related to sarcopenia. A composite assessment combining gait speed, chair stand and balance testing has been proposed as a straightforward and relatively rapid way to evaluate performance.130

Management of sarcopenia should address frailty, nutritional status, and IBD activity. Optimisation of nutrition (diet and supplements as required), encouragement of physical activity, and effective control of intestinal inflammation are central, as reducing inflammation has direct benefits on muscle metabolism.

Diet and supplementsIn patients with sarcopenia, it is essential to ensure adequate protein intake for muscle regeneration and maintenance. The diet should therefore include protein sources such as red meat, fish, chicken, eggs and pulses. If requirements cannot be met through diet alone, supplementation with protein, and even essential amino acids, may be considered. Evidence on the effect of protein supplementation on muscle health in patients with IBD is very limited and not always consistent.147 An adequate intake of vitamins and minerals particularly linked to muscle health, such as vitamin D and calcium, should also be ensured. In this regard, although from a very different patient group, vitamin D supplementation (2000 IU/day of cholecalciferol for an average of 14 months) in children with IBD improved both bone mineral density (BMD) and muscle strength.148

Physical exerciseAvailable evidence suggests that physical activity may improve sarcopenia, although studies in older or frail patients with IBD are scarce. A pilot study in patients with inactive or mildly active CD showed that three months of muscle training improved strength and quality of life, with no effect on disease activity.149 A controlled trial in patients with CD, randomised to either a six-month resistance and impact training programme or a sedentary lifestyle, confirmed that those in the exercise programme achieved significantly better BMD and muscle function than patients in the control group.150 In general, exercise interventions are most effective when aimed at improving muscle strength and endurance, with benefits typically seen after 10–12 weeks of training. Aerobic exercise is usually less feasible for these patients and its benefits may be more limited. As part of the European Union’s health promotion and quality-of-life strategy, the Vivifrail programme has been developed and is widely used. It consists of simple, structured exercise tables designed for older people, which can be easily applied and performed at home.151

Recommendations:

- •

We recommend assessing physical performance quickly and simply using gait speed, the chair stand test, and balance tests.

- •

In cases of sarcopenia, we recommend ensuring adequate protein intake and encouraging strength training exercises for at least 10–12 weeks to achieve improvements in strength and endurance. To this end, we suggest using tailored programmes such as Vivifrail to facilitate exercise at home.

Comorbidity is defined as the presence of one or more additional diseases or disorders that coexist with a primary disease in the same patient, whether they are independent of the primary condition. Comorbidity can influence the clinical course, prognosis, and treatment of IBD. In older patients with IBD, the prevalence of comorbidities exceeds 13%,56 which may be related to ageing-associated inflammation.152,153 Moreover, multimorbidity is linked to greater complexity in clinical management, as well as reduced quality of life and life expectancy.

Regardless of age, comorbidities are often used as an exclusion criterion in clinical trials, leading to their under-representation and leaving an important gap in the available evidence.53,154 Indeed, in older patients with IBD, it is comorbidities—rather than age itself—that have been associated with delayed initiation of immunosuppressive treatments, particularly in CD.155

Patients with IBD and comorbidities are more likely to experience certain complications, such as thrombosis, compared with those without comorbidities.156 Several studies have shown an increased risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with IBD, alongside non-traditional risk factors compared with the general population, such as younger age, female sex, and disease activity.157,158 In this context, it has been observed that controlling inflammation with agents such as anti-TNFs may help reduce cardiovascular risk, over and above their direct immunological effect.159

In terms of metabolic disease, recent studies indicate patients with IBD are twice as likely to develop type 2 diabetes.160–163 Alterations in the gut microbiota have been hypothesised as a potential cause,161 although a causal correlation has not been firmly established. Changes in the gut microbiota can lead to alterations in local and systemic immunity, which in turn can contribute to systemic disorders such as obesity, atherosclerosis, or diabetes. Indeed, the prevalence of obesity among patients with IBD has increased in recent decades, with an estimated 15–40% of adult patients classified as obese, irrespective of IBD subtype.164,165

The risk of neoplasia is also higher in patients with IBD, independent of treatment.166 Several studies report that the IBD population faces an increased risk of malignancies due to chronic inflammation itself—as in the case of colorectal cancer and cholangiocarcinoma.117 Older age is an independent risk factor for many cancers associated with IBD and its treatment, particularly with thiopurines.84 Conversely, a more recent systematic review and meta-analysis167 showed that overall cancer risk in IBD patients over 60 years of age was not increased by anti-TNF therapy (OR: 0.90; 95% CI: 0.64–1.26).

An increased risk of neurological disorders has also been identified. The relationship between IBD and neuroinflammation is complex, but the bidirectional interaction within the gut–brain–microbiome axis may play a fundamental role in the pathogenesis of dementia-related diseases.168 Indeed, some studies have shown an increased risk of Parkinson’s disease, autism, and Alzheimer’s disease.49,168,169

Polypharmacy in patients with inflammatory bowel diseaseThe World Health Organization defines polypharmacy as the concurrent and excessive use of several medicines at a given time.170 However, most studies describe it quantitatively as the concurrent use of five or more medicines, with “severe polypharmacy” referring to use of more than ten drugs.171 Within this concept, it is important to distinguish between appropriate polypharmacy (medications required for the treatment of disease), inappropriate polypharmacy (off-label use, self-medication, chronic misuse of drugs), and the use of high-risk medicines due to their potential for interactions, as each has different clinical implications.172

Polypharmacy is currently a major health problem, associated with adverse effects, poor therapeutic adherence, cognitive changes, falls, undertreatment of chronic conditions, drug–drug interactions, hospital admissions, and even mortality.173–178 A recent systematic review estimated the prevalence of polypharmacy in the adult population at 37% (31–43%), rising to 45% (37–54%) in those over 65 years of age, particularly in the presence of chronic diseases and comorbidities.176–179

IBD is a chronic condition requiring long-term medication and is associated with different comorbidities, so the presence of polypharmacy is to be expected.178–183 To this, we must add the impact of patient ageing and disease progression.184–186 Nevertheless, polypharmacy in IBD has been little studied, and published data show it also affects this population, with prevalence ranging widely from 18 to 50%. It is particularly relevant in older patients, in whom rates of up to 86% have been reported, with 45% severe polypharmacy and 35% inappropriate medication use.187–189 Other associated factors include the presence of comorbidities (particularly psychiatric disorders), patient dependency, and long disease duration.187,189–191

The drugs most frequently consumed are analgesics, antihypertensives, proton pump inhibitors, and psychotropic agents.181 A Danish study observed that drug consumption was associated with recent diagnosis of IBD, particularly in older patients, with increased use of antidepressants, opioids, and analgesics, among others.192

The prognosis and clinical implications of polypharmacy in this setting are less well known. Beyond the potential harm of some widely used drugs, studies have linked polypharmacy with poorer quality of life, lack of adherence to treatment, and even a higher likelihood of clinical relapse in IBD.187–189

It is essential to have adequate tools to manage polypharmacy in patients with chronic diseases. This requires a thorough review of all the drugs a patient is taking, in order to identify polypharmacy and address it through a multidisciplinary approach. Collaboration across specialties—especially geriatrics—is key to minimising the use of inappropriate or high-risk medicines, thereby optimising the comprehensive management of associated diseases and improving patient outcomes.

Based on the available evidence,193 systematic and regular reviews of medication are recommended, prioritising only essential drugs and avoiding those that may adversely affect gastrointestinal function, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), certain antibiotics, or diuretics in patients with ileostomies.194Table 6 shows interactions with the drugs most commonly used in IBD.

Interactions with the most common IBD drugs.

| Treatment | Potential risks | Preventive measures | Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mesalazine | Kidney damage | Renal function monitoring | Thiopurines |

| Steroids | HT | Short doses and doses not exceeding 60 mg/d | - |

| DM | |||

| Osteoporosis/fractures | Vitamin D and calcium | ||

| Infections | |||

| Glaucoma/cataracts | Vaccination | ||

| Psychiatric disorders | |||

| Thiopurines | Infections | Avoid in people over 65 years of age | Allopurinol |

| Warfarin | |||

| Mesalazine | |||

| Lymphoma | Vaccination | Cotrimoxazole | |

| CCNM | Reducing exposure | ACE inhibitors | |

| Urothelial neoplasms | Dermatological control | Cimetadine | |

| Methotrexate | Hepatoxicity | Vaccination | Sulfasalazine |

| Liver function monitoring | |||

| Infections | Avoid in case of chronic hepatitis (HBV, HCV) | ||

| TNF inhibitor | Infections | Vaccination | - |

| Melanoma risk | Dermatological control | ||

| TB | Latent TB screening | ||

| Heart failure | Cardiological assessment | ||

| Vedolizumab | Respiratory infections | Vaccination | - |

| Ustekinumab | No specific risk identified | - | |

| Risankizumab | |||

| Tofacitinib | Herpes zoster | Vaccination | Ketoconazole, fluconazole |

| Filgotinib | Thromboembolism | Avoid or doses of 5 mg (in case of hepatic insufficiency) | |

| Upadacitinib | Cardiac events | Cardiological assessment | Valsartan |

| Neoplasm |

CCNM: non-melanoma skin cancer; DM: diabetes mellitus; HT: hypertension; ACEI: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; TB: tuberculosis; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus.

Deprescribing should be performed safely and gradually, avoiding adverse effects such as rebound or withdrawal syndromes, with close monitoring of the patient’s clinical course. Patient education and empowerment are also crucial, encouraging active participation in treatment optimisation and promoting lifestyle changes as a complementary strategy.

Interdisciplinary coordination between gastroenterologists, primary care physicians, and pharmacists is also essential to effectively reduce polypharmacy and improve clinical outcomes in patients with IBD.

Recommendations:

- •

We suggest simplifying drug regimens whenever possible, reducing the number of doses and tablets to improve adherence and minimise errors.

- •

We suggest considering tablet size and assessing the patient’s swallowing ability.

- •

In patients with polypharmacy, we recommend reviewing prescribed medicines, assessing the need for continuation, and considering potential drug–drug interactions.

Psychosocial factors are crucial in the comprehensive management of patients with IBD, especially those who are frail and/or older. The interplay between physical frailty and psychological vulnerability often leads to suboptimal clinical outcomes and reduced quality of life. IBD can significantly affect psychosocial functioning through the chronic stress of managing a long-term condition. Frailty and advanced age can exacerbate this burden, resulting in an increased risk of psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety.191,192 The gut–brain connection is well recognised, with studies showing that systemic inflammation can affect brain function and vice versa.195

Social isolation is another critical factor that negatively impacts the health of older IBD patients. A lack of a solid support network is associated with poorer therapeutic follow-up and reduced treatment adherence.196 Some studies suggest that social support independently improves health outcomes197; indeed, absence of a partner has been associated with greater loneliness and social isolation. Partners can provide crucial support, potentially buffering the effects of stress.12,198 Among older patients with IBD, 24% experience deterioration in social domains.63 Building support systems—whether family-based, social, or patient groups—is vital to improve emotional and social wellbeing.198 One study has indicated that strong social support reduces the risk of disease progression in middle-aged patients with CD.199 Although improving social support in patients with IBD appears to be a promising strategy, its impact has not yet been adequately evaluated.

New patient care modalities also need to be considered from a social perspective. Digital technologies have transformed patient management, increasing the use of telemedicine (by phone or email). On the one hand, this reduces travel for patients with restricted mobility and lowers stress associated with hospital visits. On the other, effectiveness depends on digital literacy and access to suitable devices. In-person care remains indispensable when detailed clinical evaluation or urgent intervention is required. It is therefore important to individualise decisions, taking into account both medical and social needs in each case.199,200

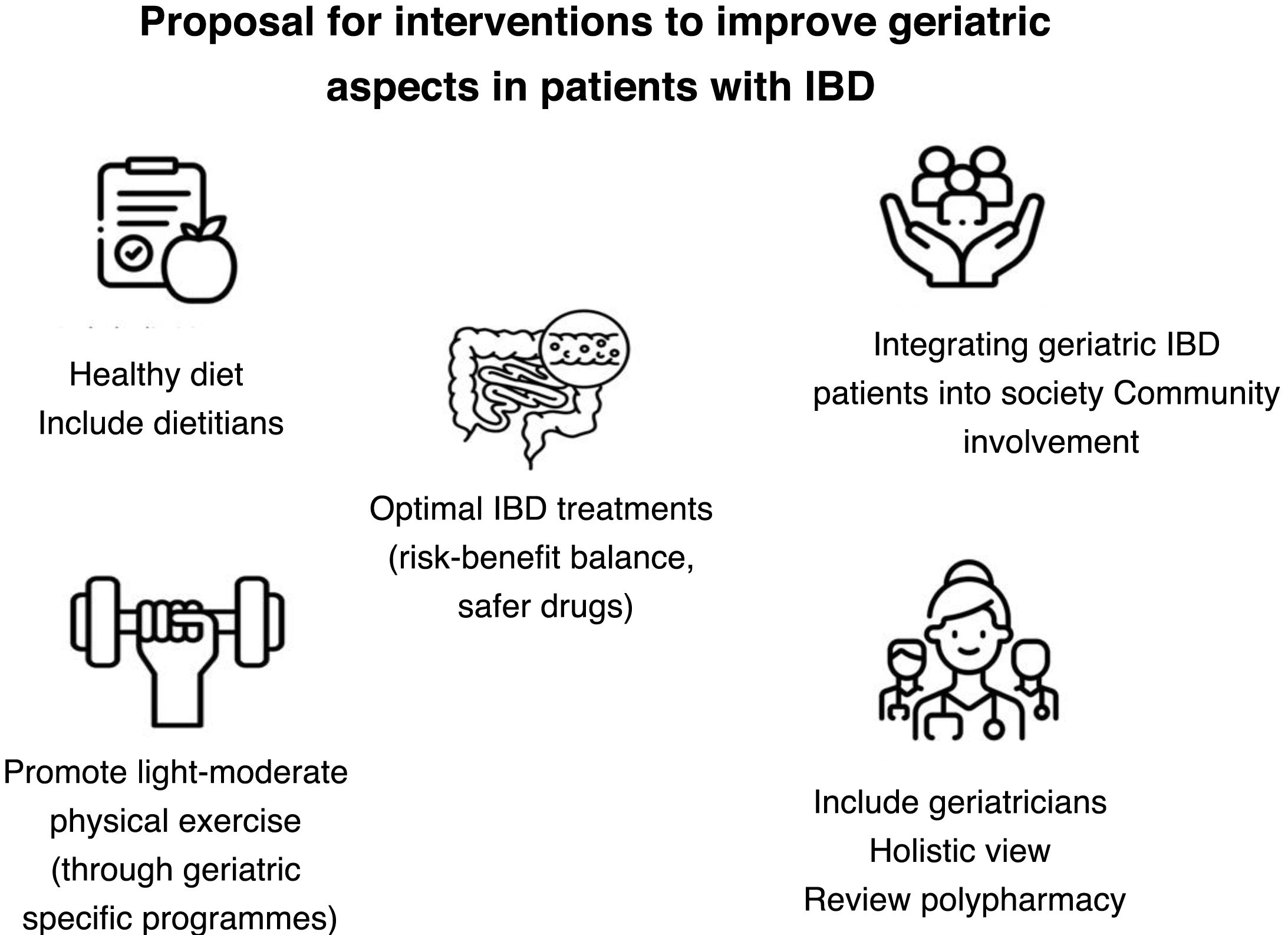

Finally, tailored psychosocial interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapy, stress management, and group interventions have been shown to improve quality of life in IBD patients.182,201 It is essential to implement strategies that foster psychological resilience and patient autonomy, while addressing the specific barriers faced by frail and older patients. Healthcare professionals should be aware of the impact of frailty and age on mental and social health, and work to integrate supportive strategies into routine care202 (Fig. 4).

Recommendations:

- •

We recommend assessing the patient’s medical and social needs.

- •

We suggest encouraging the creation of multidimensional support systems, promoting family, social and community networks that provide personalised care and reduce the risk of isolation and depression.

- •

We suggest developing strategies that strengthen patient resilience and autonomy to help prevent frailty.

Indicating investigations in frail patients with IBD is highly complex. The fundamental principle is that decisions must be individualised. No guideline or tool can offer absolute certainty as to whether a given investigation is indicated in a specific patient. What can be defined are the factors to evaluate and the basic principles to guide decision-making. In this section, we focus on colonoscopy as an example, since it is the most common invasive procedure in this population203; however, the considerations apply equally to other investigations. The main factors to consider when determining the appropriateness of an investigation are:

- 1

Degree of frailty. Relatively simple classifications can be used to determine the level of frailty. While in specific cases a full Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) may be required, a quicker scale such as the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) will usually suffice. According to frailty level, patients can be grouped as follows:

- (a)

Advanced frailty. IF-VIG > 0.5 or CFS ≥ 7; patients are fully dependent, bedbound or terminal. Diagnostic–therapeutic goals are to ensure comfort and symptom control. Endoscopic procedures are not indicated due to their short life expectancy and high risk of complications.

- (b)

Mild-moderate frailty. IF-VIG 0.2–0.5 or CFS 5–6. The goals are to achieve clinical benefit by promoting autonomy and quality of life, but not to prolong survival. Screening procedures are not indicated, as they are not useful given the limited life expectancy. Diagnostic or therapeutic procedures may be considered only if results are expected to lead to interventions that clearly improve functional status or quality of life.

- (c)

No frailty or pre-frailty. IF-VIG < 0.2 or CFS 1–4. Diagnostic–therapeutic goals are the same as in the general population, and no restrictions are applied.

- (a)

- 2

Indication for the test: as already partially discussed in the previous section, we will have to determine in which category we classify the test. We will distinguish:

- (a)

Screening tests: These would only be indicated in patients without frailty. In general, this is linked to a long life expectancy. In the uncommon case of patients without frailty but with life expectancy limited by comorbidities —e.g., cardiovasculardisease — the risk–benefit of colonoscopy should be assessed and the procedure only indicated if the balance is unequivocally favourable.

- (b)

Diagnostic and/or therapeutic procedures: These would be indicated in all patients without advanced frailty. In such cases, the potential risk of complications and the expected benefit of colonoscopy must be carefully weighed, and the procedure should only be recommended if the risk–benefit balance is clearly favourable, following the classical principle of primum non nocere.

- (a)

- 3

Principles, preferences and values of each patient: The criteria set out above are subordinate to the principle of patient autonomy. That is, we must respect the decision of a patient who refuses any examination if they prefer to maintain a less medicalised lifestyle (regardless of frailty status). This is particularly relevant given the limited scientific evidence on the usefulness of screening colonoscopy in reducing mortality in patients with IBD. In such cases, our only obligation is to provide unbiased information on the risks and benefits of undergoing or foregoing the test, and to ensure that the patient understands this information. The only exception is that, in line with the ethical principle of non-maleficence, we have an ethical duty to refuse to recommend or perform a procedure if, in our professional judgement, the risk–benefit balance is unfavourable for the patient.204

Recommendations:

- •

We suggest performing any examination only when the risk–benefit balance is clearly favourable, avoiding unnecessary interventions in patients at high risk of complications.

- •

We recommend respecting patient autonomy in decision-making, ensuring clear information on risks and benefits, while avoiding procedures in which risk clearly outweighs benefit.

- •

In patients with advanced frailty (IF-GIV > 0.5 or CFS ≥ 7), we recommend against endoscopic procedures.

- •

In patients with moderate-mild frailty (IF-VIG 0.2−0.5 or CFS 5–6), we recommend avoiding screening colonoscopy and performing diagnostic or therapeutic procedures only where there is a clear clinical benefit.

This position paper was developed based on a critical review of the literature and expert consensus from the Spanish Working Group on Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (GETECCU). No individual patient data were used, nor was the conduct of clinical studies required; therefore, approval from a research ethics committee was not necessary. The document was developed in accordance with the ethical principles of independence, transparency, and scientific rigour.

FundingNo funding was received for this paper.

The authors have received funding for research, training, attendance at scientific meetings and consultancy from the following companies:

M. Mañosa: MSD, AbbVie, Takeda, Janssen, Pfizer, Ferring, Kern Pharma, Dr. Falk Pharma, Galapagos, Tillots, Lilly and Faes Farma.

M. Calafat: Takeda, Johnson and Johnson, Faes Farma, Falk, Abbvie, Pfizer, Tillot's Pharma, Adacyte Therapeutics, Ferring, Gilead, Kern Pharma and MSD.

EF and FR declare no conflicts of interest.

F. Mesonero: MSD, AbbVie, Takeda, Janssen, Pfizer, Ferring, Kern Pharma, Dr. Falk Pharma, Celltrion Healthcare, Galapagos, Chiesi, Tillots Pharma, Lilly and Faes Farma.

C. Suarez: Abbvie, MSD, Lilly, Pfizer, Jansen, Takeda, Thillots, Ferring, Chiesi and Kern pharma.

SG-L and FL declare no conflicts of interest.

X. Calvet: MSD, Abbvie, Pfizer, Kern Pharma, Takeda, Janssen, Sandoz, Galapagos, Lilly, Shire Pharmaceuticals and Vifor Pharma.

E. Domènech: AbbVie, Adacyte Therapeutics, Biogen, Celltrion, Ferring, Galapagos, Gilead, GoodGut, Imidomics, Janssen, KernPharma, Lilly, MSD, Pfizer, Roche, Samsung, Takeda and Tillots.

A. Gutiérrez-Casbas: Abbvie, Lilly, J&J, Pfizer, Kern, MSD, Takeda, Adacyte, Falk, FAES, Sandoz, Fresenius Kabi, Ferring, Tillots, Roche and GSK.

I. Ordás: Abbvie, MSD, Pfizer, Takeda, Janssen, Kern Pharma, Chiesi, Falk Pharma, and Faes Farma. Research support from Abbvie and Faes Farma.

L. Menchén: MSD, Abbvie, Takeda, Janssen, Pfizer, Biogen, Galapagos, Kern Pharma, Lilly, Adacyte, Tillotts, Dr. Falk Pharma, Ferring, Medtronic and General Electric.

F. Rodríguez-Moranta: Lilly, Takeda, J&J, FAES Pharma, Falk, Abbvie, Pfizer, Tyllots, Ferring and Kern Pharma.

Y. Zabana: AbbVie, Adacyte, Alfasigma, Almirall, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dr Falk Pharma, Faes Pharma, Fresenius Kabi, Ferring, Galapagos, Janssen, Johnson&Johnson, Kern, Lilly, MSD, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sanofi, Shire, Takeda, and Tillotts Pharma.