Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are the leading cause of death worldwide. Therefore, it is essential to understand their relationship and prevalence in different diseases that may present specific risk factors for them. The objective of this document is to analyze the specific prevalence of CVD in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), describing the presence of classical and non-classical cardiovascular risk factors in these patients. Additionally, we will detail the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis in this patient group and the different methods used to assess cardiovascular risk, including the use of risk calculators in clinical practice and different ways to assess subclinical atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction. Furthermore, we will describe the potential influence of medication used for managing patients with IBD on cardiovascular risk, as well as the potential influence of commonly used drugs for managing CVD on the course of IBD. The document provides comments and evidence-based recommendations based on available evidence and expert opinion. An interdisciplinary group of gastroenterologists specialized in IBD management, along with a consulting cardiologist for this type of patients, participated in the development of these recommendations by the Spanish Group of Work on Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (GETECCU).

Las enfermedades cardiovasculares (ECV) son la primera causa de muerte en el mundo por ello es fundamental conocer su relación y prevalencia en distintas enfermedades que pueden presentar factores de riesgo específicos para las mismas. El objetivo del presente documento es analizar la prevalencia específica de las ECV en los pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII), describiendo la existencia de los factores de riesgo cardiovascular clásicos y no clásicos en estos pacientes. Asimismo, detallaremos la fisiopatología de la aterosclerosis en este grupo de pacientes, y las distintas formas de medir el riesgo cardiovascular, incluyendo el empleo de calculadoras de riesgo en la práctica clínica y las diferentes formas de objetivar la aterosclerosis subclínica y la disfunción endotelial. Igualmente, se explicará la potencial influencia sobre el riesgo cardiovascular de la medicación utilizada para el manejo de los pacientes con EII y, de forma inversa, la posible influencia de los fármacos más comúnmente empleados para el manejo de las ECV sobre el curso de la EII. Finalmente, en el documento se establecen comentarios y recomendaciones basadas en la evidencia disponible, y en la opinión de expertos. En la elaboración de estas recomendaciones del Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (GETECCU) ha participado un grupo interdisciplinar que incluía a gastroenterólogos expertos en el manejo de la EII y a un cardiólogo consultor para este tipo de pacientes.

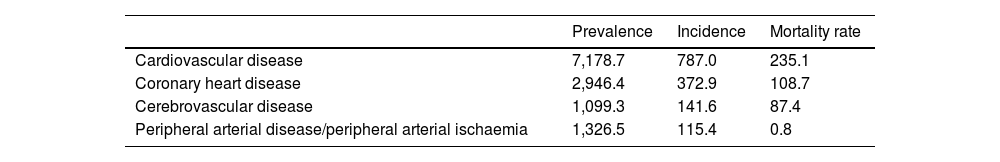

According to the World Health Organization, cardiovascular disease (CVD) encompasses a range of disorders of the heart and blood vessels, including coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral arterial disease, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, rheumatic heart disease and congenital heart disease.1 CVD is the leading cause of death worldwide, being responsible for 19.4 million deaths in 2021. Three quarters of deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries and in Europe they account for more than half of annual deaths. In 2021, the prevalence was estimated to be 7,178.7 cases/105 population and the incidence, 787.0 cases/105 population.2 The CVDs with the greatest impact are coronary heart disease (CHD) and cerebrovascular disease, which accounted for 84% of deaths in 2021 and 65.5% of incident CVD cases3–5 (Table 1).

Prevalence, incidence and mortality rate in the general population in 2021.

| Prevalence | Incidence | Mortality rate | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular disease | 7,178.7 | 787.0 | 235.1 |

| Coronary heart disease | 2,946.4 | 372.9 | 108.7 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1,099.3 | 141.6 | 87.4 |

| Peripheral arterial disease/peripheral arterial ischaemia | 1,326.5 | 115.4 | 0.8 |

In patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) it is well established that there is an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE).

In a classic study published back in 1964 by the Oxford group, pulmonary embolism was described as one of the complications most associated with death in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC).6 In fact, international guidelines on the management of VTE and pulmonary embolism describe IBD as a moderate risk factor (odds ratio [OR]: 2–9) for VTE.7

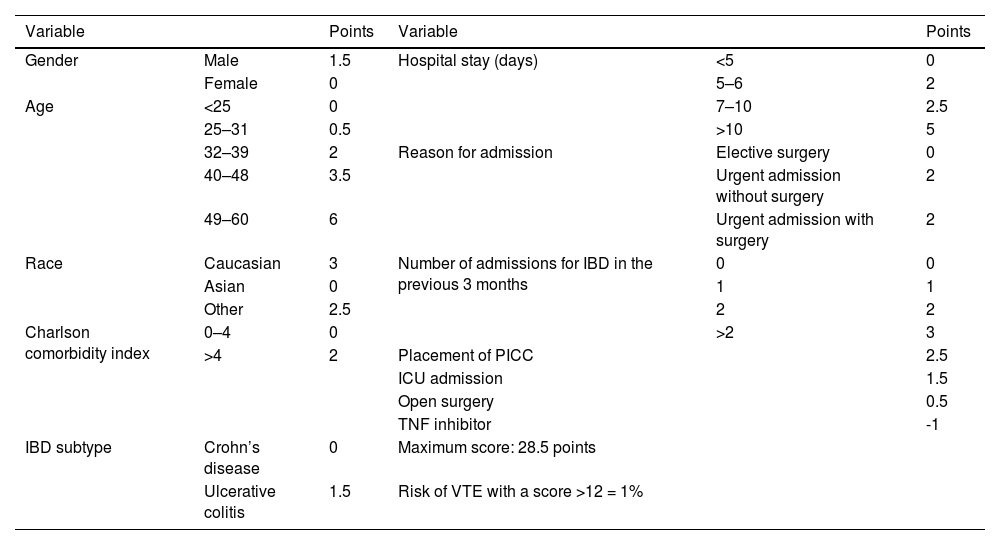

Three meta-analyses found that the relative risk (RR) of VTE was 1.96 to 2.20 compared to IBD-free controls,8–10 and a meta-analysis of risk in pregnant women with IBD found the RR during pregnancy and in the postpartum period to be 2.13 and 2.61 respectively.11 The risk of VTE is elevated both in remission (hazard ratio [HR]: 2.1) and during IBD flare-ups (HR: 8.4).12 A recent paper13 analysed the incidence of VTE within 90 days of discharge in patients with IBD; the main risk factors for developing a VTE were longer admissions, older age, male gender and emergency admission. To prevent these events, appropriate prophylactic anti-thrombotic therapy is therefore recommended in inpatients and, in some cases, in outpatients.13–17 A risk staging system has been proposed (Table 2,13) for identifying patients with IBD at increased risk of VTE after discharge which may be helpful for use in clinical practice. In a recently published German series18 including 333,975 admissions of patients with Crohn's disease (CD), VTE was an independent factor for increased mortality in patients admitted with CD (OR: 9.31, 95% confidence interval [95% CI]: 7.54–11.50). Not only is VTE associated with a worse clinical outcome, but it also entails a significant burden in terms of economic cost in the treatment of patients with IBD.19

Risk staging system for VTE 90 days after discharge in patients with IBD.

| Variable | Points | Variable | Points | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 1.5 | Hospital stay (days) | <5 | 0 |

| Female | 0 | 5–6 | 2 | ||

| Age | <25 | 0 | 7–10 | 2.5 | |

| 25–31 | 0.5 | >10 | 5 | ||

| 32–39 | 2 | Reason for admission | Elective surgery | 0 | |

| 40–48 | 3.5 | Urgent admission without surgery | 2 | ||

| 49–60 | 6 | Urgent admission with surgery | 2 | ||

| Race | Caucasian | 3 | Number of admissions for IBD in the previous 3 months | 0 | 0 |

| Asian | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Other | 2.5 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index | 0–4 | 0 | >2 | 3 | |

| >4 | 2 | Placement of PICC | 2.5 | ||

| ICU admission | 1.5 | ||||

| Open surgery | 0.5 | ||||

| TNF inhibitor | -1 | ||||

| IBD subtype | Crohn’s disease | 0 | Maximum score: 28.5 points | ||

| Ulcerative colitis | 1.5 | Risk of VTE with a score >12 = 1% | |||

IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; ICU: intensive care unit; PICC: peripherally inserted central catheter; TNF: tumour necrosis factor; VTE: venous thromboembolism.

Data on the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (atherosclerotic CVD) are inconsistent. Some studies report no higher risk than in the general population,20–24 while others report a lower risk.25,26 However, five meta-analyses9,27–30 and several recent studies31,32 suggest an increased risk of CHD and stroke, ranging from 15–25%, compared to the general population, after adjusting for cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF) (Appendix B Supplementary Table 1). As a result, several expert groups advocate assessing atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in patients with IBD.33

The risk of atherosclerotic CVD is increased in both CD and UC patients, although some studies have found that the risk is higher in those with CD.34–36 The increased risk is higher in females than in males, and in younger compared to older patients.29,32,34–36 A study looking at the characteristics of patients with premature or extremely premature atherosclerotic CVD (patients younger than 55 or under 40 respectively) found that the percentage of patients with IBD in these age groups with atherosclerotic CVD was higher than in control patients37 (Appendix B Supplementary Table 2).

The recently published results for incidence of acute arterial events, including CHD, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral arterial disease or death from acute arterial events, from the analysis of UK biobank data including more than 450,000 participants, in which data from 5,094 patients with IBD were matched with data from 20,376 controls, found an increased risk of such events in patients with IBD, particularly in male patients younger than 55 and in women under 65. Notably, both elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and IBD severity were independent predictors of acute arterial events in these patients.38

It is unclear whether this increased risk of CVD is also associated with increased CVD-related death. Meta-analyses have found no increase in CVD-related mortality rates9,30,39 and it has even been found that survival in patients with IBD with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) can be 25% longer than in patients without IBD.40 However, a recent German series18 reported that VTE is an independent factor for increased mortality risk in patients admitted with CD (OR: 9.31; 95% CI: 7.54–11.50), and data from the Norwegian IBSEN cohort,41 after 30 years of follow-up, show the CVD mortality rate in patients with IBD to be higher than in the general population, both for UC (HR: 1.51 [1.10–2.08]) and CD (HR: 2.04 [1.11–3.77]).

Summary and recommendation

- -

Patients with IBD have an increased risk of VTE and atherosclerotic CVD compared to the general population which is higher still in both young and female patients.

- -

Prophylactic antithrombotic treatment is recommended for patients with IBD admitted for any reason. Continuation of such treatment at hospital discharge should be considered in patients at high risk of thrombosis (Table 2).

- -

The increased risk of CVD may also be associated with an increased risk of CVD-related death, but the data are inconclusive.

Classic CVRF are clinical factors described in the Framingham Heart Study which contribute to an increased risk of developing atherosclerotic CVD. These factors are age, gender, total cholesterol level, LDL-cholesterol level, systolic blood pressure (BP), antihypertensive treatment, diabetes mellitus (DM) and smoking.42 We have to add to these factors others identified since then, such as family history of cardiovascular disease, ethnicity, obesity, sedentary lifestyle and diet. In addition to the risk attached to these factors individually, a multiplier effect has been found when several of them exist simultaneously.43

The prevalence of these CVRF in our setting is high.44,45 In rich European countries 23.4% of males and 15.6% of females are smokers; the prevalence of insufficient physical activity is 32%; 20.6% of the population has hypertension (HT); 18.8% of men and 18.1% of women have dyslipidaemia; 5.8% have DM; and 22.3% are obese.

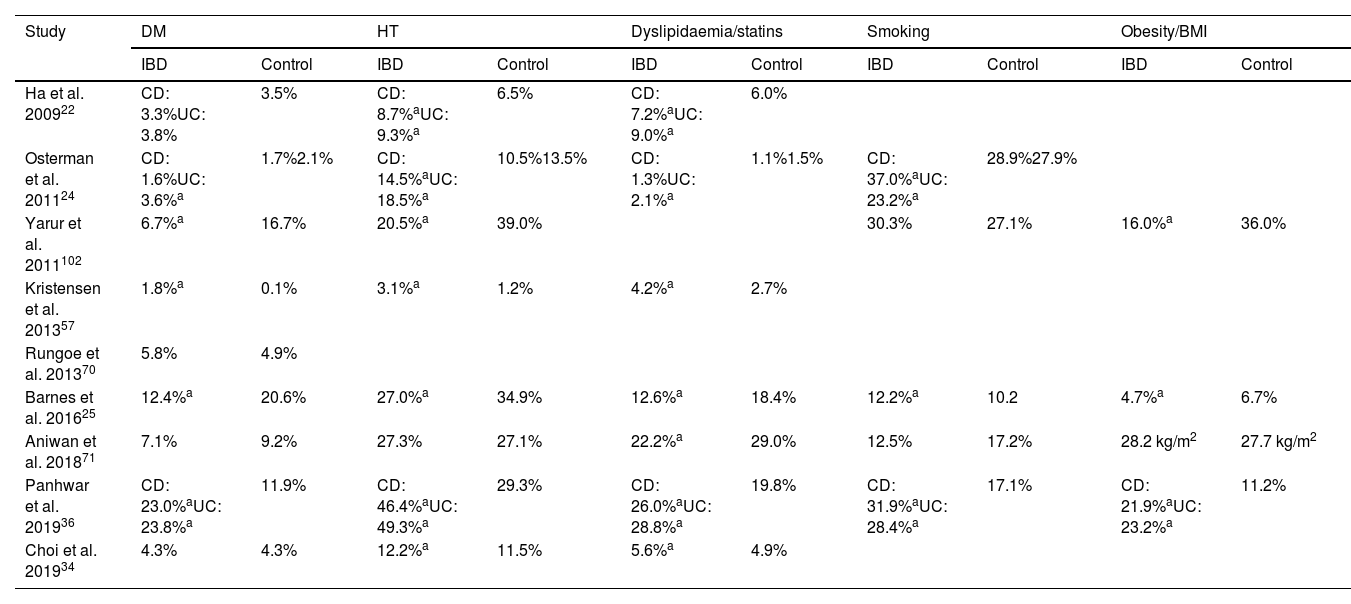

In studies which have assessed cardiovascular risk in IBD, the rate of CVRF in patients with IBD compared to control groups is variable, with some studies showing a lower rate, some showing a similar rate and others showing a higher rate of some of the classic CVRF29,46 (Table 3). Similarly, studies which directly analysed the prevalence of CVRF in patients with IBD show conflicting results. A Danish population-based study found that patients with IBD had lower BP, total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol values, with blood glucose levels and body parameters similar to the general population.47 In contrast, a US study based on a population-based health survey found that patients with IBD had a higher prevalence of high BP, DM, hypercholesterolaemia and insufficient physical activity and a similar prevalence of smoking and obesity compared to the general population; these differences disappeared in patients over the age of 65.48 Lastly, a recent cross-sectional study in French and Belgian reference centres reported that two thirds of UC patients have at least one CVRF.49

Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in studies examining the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in patients with IBD.

| Study | DM | HT | Dyslipidaemia/statins | Smoking | Obesity/BMI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBD | Control | IBD | Control | IBD | Control | IBD | Control | IBD | Control | |

| Ha et al. 200922 | CD: 3.3%UC: 3.8% | 3.5% | CD: 8.7%aUC: 9.3%a | 6.5% | CD: 7.2%aUC: 9.0%a | 6.0% | ||||

| Osterman et al. 201124 | CD: 1.6%UC: 3.6%a | 1.7%2.1% | CD: 14.5%aUC: 18.5%a | 10.5%13.5% | CD: 1.3%UC: 2.1%a | 1.1%1.5% | CD: 37.0%aUC: 23.2%a | 28.9%27.9% | ||

| Yarur et al. 2011102 | 6.7%a | 16.7% | 20.5%a | 39.0% | 30.3% | 27.1% | 16.0%a | 36.0% | ||

| Kristensen et al. 201357 | 1.8%a | 0.1% | 3.1%a | 1.2% | 4.2%a | 2.7% | ||||

| Rungoe et al. 201370 | 5.8% | 4.9% | ||||||||

| Barnes et al. 201625 | 12.4%a | 20.6% | 27.0%a | 34.9% | 12.6%a | 18.4% | 12.2%a | 10.2 | 4.7%a | 6.7% |

| Aniwan et al. 201871 | 7.1% | 9.2% | 27.3% | 27.1% | 22.2%a | 29.0% | 12.5% | 17.2% | 28.2 kg/m2 | 27.7 kg/m2 |

| Panhwar et al. 201936 | CD: 23.0%aUC: 23.8%a | 11.9% | CD: 46.4%aUC: 49.3%a | 29.3% | CD: 26.0%aUC: 28.8%a | 19.8% | CD: 31.9%aUC: 28.4%a | 17.1% | CD: 21.9%aUC: 23.2%a | 11.2% |

| Choi et al. 201934 | 4.3% | 4.3% | 12.2%a | 11.5% | 5.6%a | 4.9% | ||||

BMI: body mass index; CD: Crohn’s disease; DM: diabetes mellitus; HT: high blood pressure; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Despite these conflicting data, some of the classic CVRF have been associated to a greater or lesser extent with IBD. A meta-analysis including two case/control studies and three population-based studies reported that the risk of DM is higher in patients with IBD compared to the general population (OR/RR: 1.26, 95% CI: 1.20–1.32).28 The prevalence of obesity in patients with IBD is 15–40% and that of overweight, 20–40%.50 These rates are likely to increase over time, as from 1991 to 2008 a progressive increase in weight and body mass index (BMI) was observed in patients with CD participating in clinical trials51 and women with obesity (BMI > 30) have a higher risk of developing CD than women with a normal BMI.52 Smoking is a widely studied environmental factor in the development of IBD; the European EPI-IBD study found that 36–38% of patients with CD and 9–11% of patients with UC were smokers at diagnosis.53 In other prospective cohorts, the prevalence of active smoking was 26–39.9% in CD and 10–15.3% in UC, similar to or lower than in the respective general populations.54,55

Although classic CVRF are not more common in patients with IBD than in the general population, they influence individual cardiovascular risk. In a study following up 300 patients with IBD without classic CVRF for two years, only one patient developed an ischaemic cardiovascular event.56 Patients with IBD and atherosclerotic CVD are more likely to have classic CVRF than patients with IBD without atherosclerotic CVD.32 Lastly, patients with IBD and CVRF have an increased risk of cardiovascular events.35,36,57,58

Summary and recommendation

- -

The prevalence of classic CVRF in patients with IBD is variable in the published studies, but does not appear to be increased when compared to the general population.

- -

Classic CVRF influence individual CV risk in patients with IBD.

- -

We recommend assessing each patient individually for classic CVRF in order to detect an increased risk of CVD early, as is done in the general population.

Since the increased risk of atherosclerotic CVD in patients with IBD does not seem to be related to a higher rate of classic CVRF, it has been suggested that, as in other inflammatory diseases, cardiovascular risk modifiers (former non-classic CVRF) may have an important influence.59

Subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with inflammatory bowel diseaseSubclinical atherosclerosis has been reported to increase the risk of atherosclerotic CVD, and in individuals at intermediate cardiovascular risk, non-invasive screening for subclinical atherosclerosis may help to improve estimation of cardiovascular risk.60 Patients with IBD without CVRF or established atherosclerotic CVD have markers of subclinical atherosclerosis such as carotid intima-media thickness and arterial stiffness, or evidence of endothelial dysfunction.61–64

Role of inflammatory activity in cardiovascular riskAtherosclerosis can be considered an inflammatory disease in which immune mechanisms interact with metabolic factors to initiate, propagate and activate arterial lesions.65 In IBD, apart from inflammatory activity, activation of biomarkers associated with atherosclerotic CVD, such as D-dimer, von Willebrand factor, hyperhomocysteinaemia, oxidised LDL, fibrinogen, matrix metallopeptidases, NF-κB and interferon-γ has been described.66,67

A relationship between cardiovascular events and inflammatory activity has been reported in patients with IBD. Because most studies have been conducted on population-based cohorts or administrative databases, the association is based on indirect data, such as time since IBD diagnosis, initiation of corticosteroid therapy or proximity to IBD-related admissions. The percentage of patients with moderate or severe activity is high in the first year after IBD diagnosis.68,69 A Danish population-based study reported that the increased risk of CHD in patients with IBD was particularly high in the first three months and in the first year after IBD diagnosis.70 Several studies have reported that patients requiring corticosteroid therapy have an increased risk of atherosclerotic CVD compared to patients who do not require it during follow-up,70,71 as is also the case for patients requiring hospital admission or surgery for their IBD.35,70–72 Several studies defining IBD activity on the basis of criteria including hospital admissions, prescribing of corticosteroids or TNF inhibitors57,73 and disease-specific classification58 have found an increased risk of cardiovascular events in patients with activity compared to those in remission. Moreover, patients without flare-ups have a similar risk to individuals without IBD. The presence of these activity markers has been associated with a higher mortality rate in AMI and increased risk of re-infarction.74 The only study to have assessed cardiovascular risk based on objective parameters is a French case-control study, which found that patients with IBD who developed an arterial event were more likely to have had mean CRP levels above 5 mg/l in the previous year and previous three years.58

Psychosocial factorsAnxiety and depression are clinical conditions associated with increased cardiovascular risk and in turn, the development of CVD in these patients may aggravate the course of mental illness, with an increased risk of suicide.75 Anxiety and depression have also been studied in patients with IBD, with a higher rate in these patients, so psychological stress could have a negative influence on their cardiovascular health.76

Summary

- -

The increase in CVD in patients with IBD is not explained by classic CVRF alone.

- -

Patients with IBD show evidence of subclinical atherosclerosis in the absence of established CVRF or CVD.

- -

Inflammatory activity is associated with an increased risk of CVD and a worse prognosis for established atherosclerotic CVD.

- -

The higher rate of anxiety and depression in patients with IBD may play a role in the increased risk of CVD in these patients.

Atherosclerosis is an inflammatory disease which causes deterioration of the arterial wall through the accumulation and oxidation of lipids in the intimal layer of the wall.77 The pathogenic role of CVRF (HT, hypercholesterolaemia, smoking and DM) is well known. Moreover, the increased prevalence of atherosclerotic disease in patients with chronic inflammation (human immunodeficiency virus, rheumatoid arthritis [RA] or psoriasis), where the systemic inflammatory state acts as a stimulus for the progression of the atherosclerotic lesion,78–80 has also been widely demonstrated.

To summarise simply, atherosclerosis is not merely an accumulation of lipids in the arterial wall; it is a complex inflammatory process on a genetically predisposed arterial wall.77 It affects medium and large-calibre arteries and develops throughout life, with the first macroscopic lesions (cholesterol streaks) appearing as early as infancy and childhood, with an inflammatory rather than lipid component.77 At a microscopic or cellular level, endothelial dysfunction is the first pathological alteration to occur. This enables the passage of leucocytes, the easy adhesion of platelets and the deposition of low-density cholesterol molecules (mostly LDL), which are oxidised by activated T lymphocytes and phagocytosed by macrophages, which are then transformed into foam cells. Consequently, the release of vasogenic cytokines, smooth muscle proliferation factors which attempt to isolate the cholesterol plaque, and a reduction in endothelial nitric oxide production which decreases arterial distensibility, lead to progressive arterial stiffening. Initially arterial remodelling prevents a decrease in lumen calibre, but fibrosis and calcification eventually lead to a progressive loss of lumen calibre which, clinically, leads to chronic coronary syndromes. Acute rupture of cholesterol plaques caused by acute inflammatory or mechanical mechanisms exposes the interior of the atheroma plaque, forming a thrombus and leading to acute coronary syndromes due to vessel thrombosis.

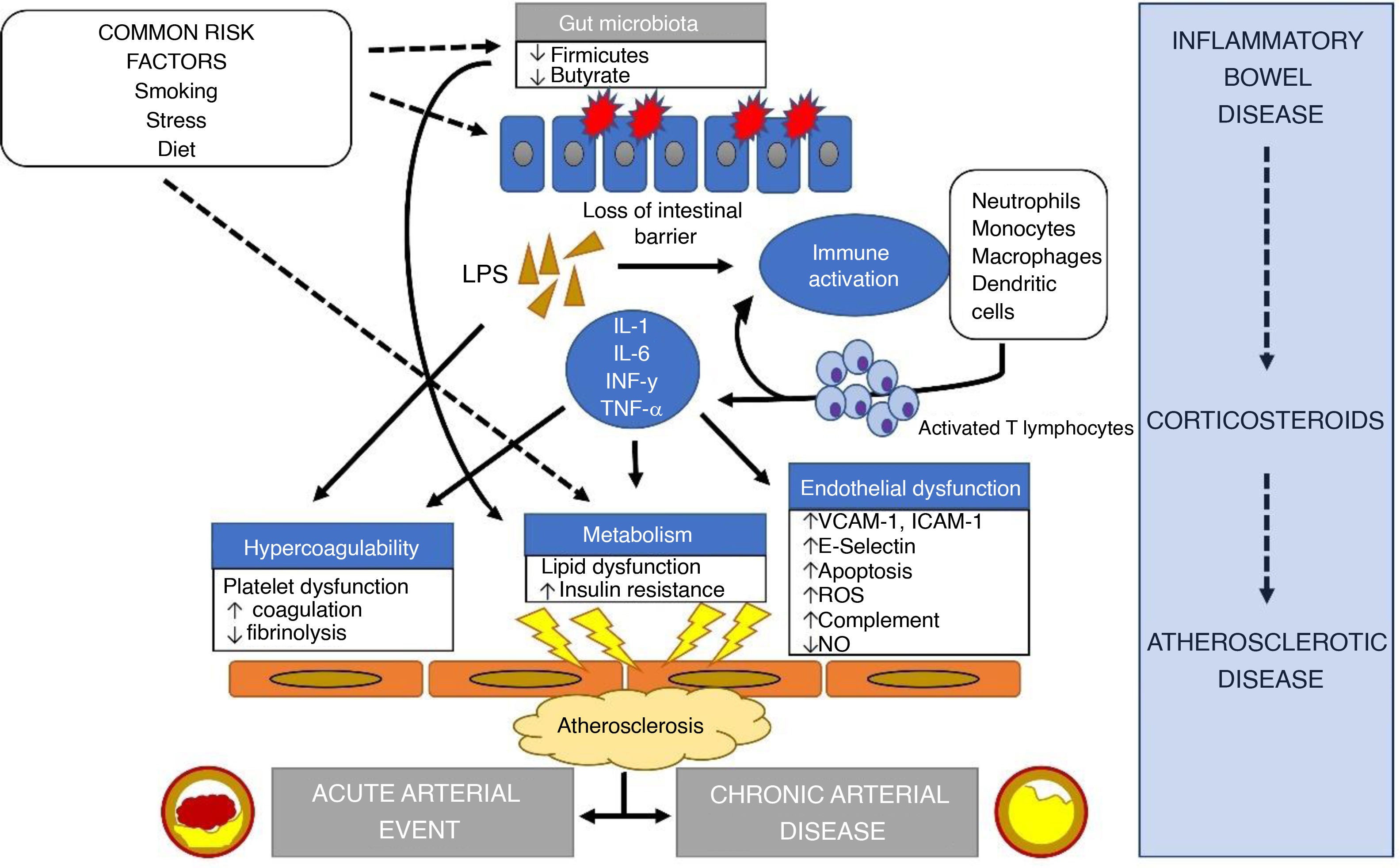

In IBD, in addition to the systemic inflammatory state, the alteration of the microbiome and the regular use of corticosteroids, which generate insulin resistance, hypertension and dyslipidaemia, contribute to the progression of arterial disease.81 The alteration of the microbiome, and in particular the decrease in bacteria in the phylum Firmicutes, appears to have pro-inflammatory consequences82 by reducing butyrate production, which can lead to obesity, insulin resistance and dyslipidaemia.83 Generally, LDL levels in patients with IBD are lower than in control patients, but HDL levels are also lower and triglycerides increased.84 It is thought that this alteration in lipid ratios may be important in the epidemiological relationship between the two diseases. Lastly, a state of hypercoagulability is created85 and the endothelial dysfunction we mentioned earlier becomes worse because of loss of intestinal barrier function, leading to the release of inflammatory cytokines into the blood (interleukin [IL]-6, IL-1, interferon-γ and TNF-α) and an increase in lipopolysaccharides.86

The pathophysiological relationship between IBD and atherosclerosis is summarised in Fig. 1.

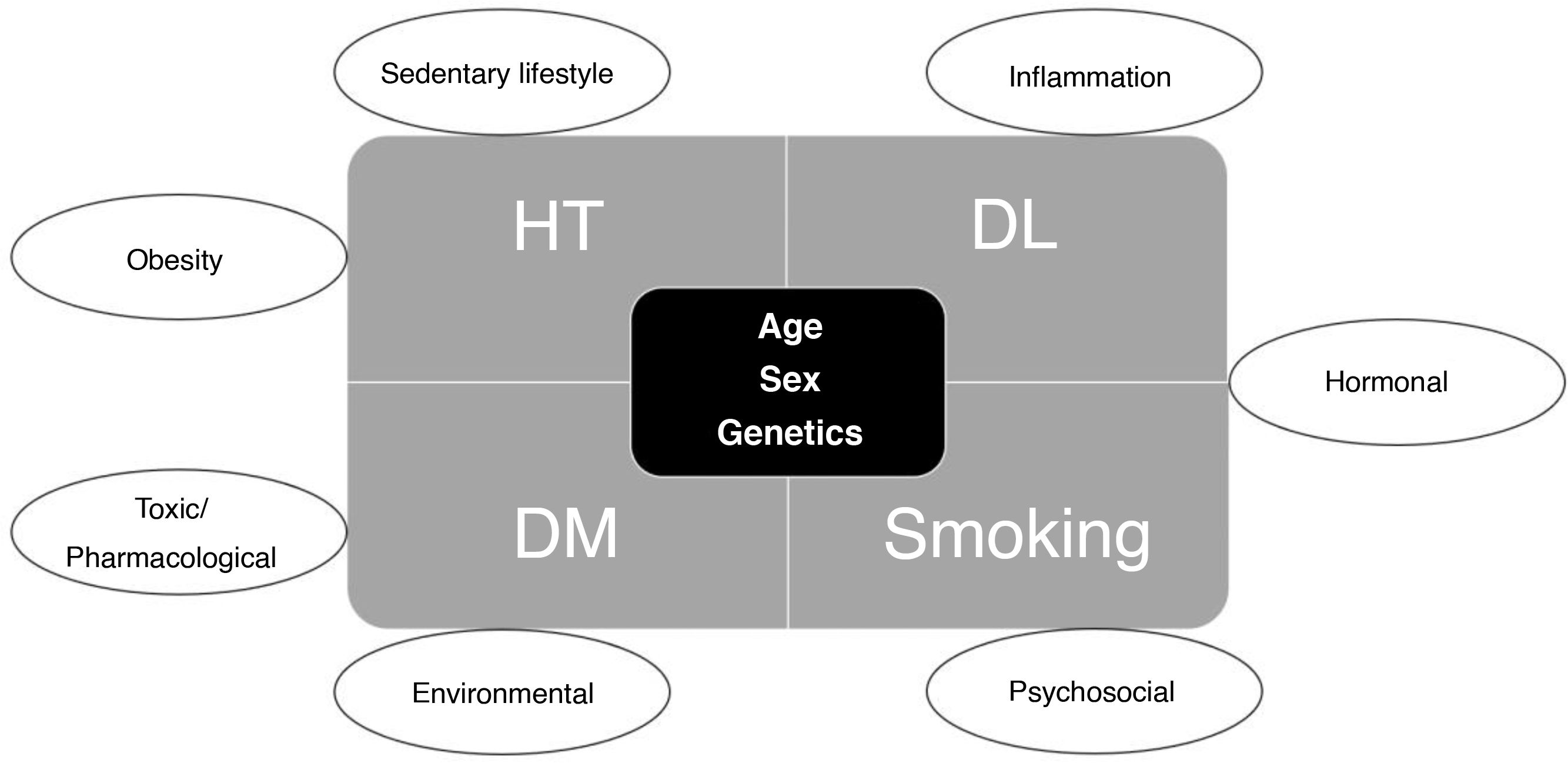

How can we measure cardiovascular risk in patients with inflammatory bowel disease? Risk calculatorsCardiovascular risk is determined by the presence of modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors. Modifiable factors include major risk factors (HT, dyslipidaemia, DM and smoking) and secondary risk factors (Fig. 2).

These risk factors should be assessed routinely to evaluate the risk of cardiovascular events and to establish appropriate primary or secondary prevention measures in patients with particular diseases or baseline risk factors (for example, age over 40, DM, hypercholesterolaemia).87

Cardiovascular risk calculators are a tool for helping objectively assess a patient’s cardiovascular risk and assisting the clinician in therapeutic decision-making, which should be guided by risk/benefit and efficiency principles. Risk calculators are not intended to replace the clinician’s integrative ability to make these decisions. There are multiple different calculators which may be more or less appropriate for risk assessment in different patients.88 The major international guidelines on cardiovascular risk recognise the atherogenic role of chronic inflammatory diseases,89–92 but they make no specific recommendations for patients with IBD. They do all agree on the modifying effect of chronic inflammatory diseases because of their pathophysiological role and, in many cases, because of the toxicity of the drugs required to treat them, as they can have their own harmful cardiovascular effects. The US guidelines for cardiovascular risk management specify that the cardiovascular risk of patients with inflammatory diseases should not be downgraded simply because there is no other evidence of atherosclerotic disease, such as coronary calcium, recognising the potential for non-calcified atheromatosis and the added risk of the procoagulant effect in these diseases.89

The decision to choose one calculator over another may also be influenced by age, the presence of major CVRF such as DM or the patient’s ethnicity. To make this process easier for clinicians, some digital tools such as U-prevent (https://u-prevent.com/) contain different calculators and help us to select the most appropriate.

In general, the recommendation of the European guidelines for the management of cardiovascular risk is that, in any patient over 40 years of age without CVD or comorbidities (DM, chronic kidney disease, familial hypercholesterolaemia or LDL > 190 mg/dl), an estimate of cardiovascular risk should be made with the SCORE2 calculator using the tables adjusted to the risk of the population of origin (Spain is classed as low-risk European, with a cardiovascular mortality incidence below 150 per 100,000 population), and the corresponding preventive measures should be established.75 The QRISK393 risk calculator has also been used in our setting, showing a good correlation with the SCORE for calculating cardiovascular risk in patients with IBD. It is even more specific for these patients, in whom the SCORE scale underestimates the 10-year risk, possibly because it does not take into account specific factors with a high prevalence in the IBD population (such as the use of corticosteroids or mental illness).

It is known that universal cardiovascular risk calculators (such as SCORE) may underestimate CVD risk in patients with IBD,46 but we do not know how to adjust these calculators for this patient group. In very young patients (under the age of 40), there is no evidence for initiating cardiovascular risk prevention measures, even if they have IBD as an isolated risk factor.

Recommendation

- -

Taking into account the experience of use, validation in a low-risk European population (including the Spanish population) and its easy accessibility, we consider it recommendable to use the SCORE2 scale for patients with IBD aged 40 and over as a tool for assessing cardiovascular risk and monitoring how any risk evolves.

It is important to detect atherosclerotic disease in subclinical stages in order to establish strategies, whether more or less intensive, for the prevention of cardiovascular events. Over the last twenty to thirty years, imaging techniques and the use of more specific biomarkers associated with cardiovascular events have made it possible to modulate the classic risk established by the usual risk calculators (see section: How can we measure cardiovascular risk in patients with IBD? Risk calculators). However, mainly in terms of primary prevention, it should be borne in mind that many of these techniques are costly and, particularly with those involving radiation, have risks for the patient. Therefore, most guidelines on cardiovascular risk prevention do not state that they should be performed routinely.

One of the simplest tests for the diagnosis of subclinical peripheral arterial disease is the ankle-brachial index. It is the ratio between the mean BP in the upper limbs and the mean BP in the lower limbs. A ratio below 0.9 indicates a disproportionate fall in BP in the lower limbs, and is diagnostic of peripheral arterial disease. In asymptomatic patients, such a result should be interpreted as a risk modifier and it could aggravate the calculation estimated by risk calculators. The test is simple and inexpensive and can be performed with a manometer, so it should be used on any patient with symptoms of claudication or as routine in cardiovascular risk assessment for the screening of peripheral arterial disease.

Imaging tests (Appendix B Supplementary Table 3) supplement cardiovascular risk assessment, but routine use is not recommended due to the lack of cost-effectiveness in population screening and the lack of methodological standardisation.75,94 Incidental diagnosis of stenosis, aneurysms, ulcers or artery dissections at any level by imaging tests (even if not performed for that purpose) leads to a diagnosis of atherosclerotic arterial disease and secondary prevention measures should be initiated. Calculation of coronary calcium, carotid intima-media thickness measured by ultrasound, carotid peak systolic velocity and the presence of atherosclerotic plaques in the carotid or femoral arteries are risk modifiers. Of these, coronary calcium estimation is the most robustly associated with cardiovascular risk and has the best risk reclassification capability, comparable to the presence of carotid and femoral atheromatous plaques and far superior to carotid intima-media measurement.95 In patients with IBD, the use of ultrasound to assess for carotid plaques has been reported to reclassify 21% of patients as being at high cardiovascular risk.96

The main characteristics, advantages and disadvantages of the most commonly used imaging tests for cardiovascular risk assessment are shown in Appendix B Supplementary Table 3.

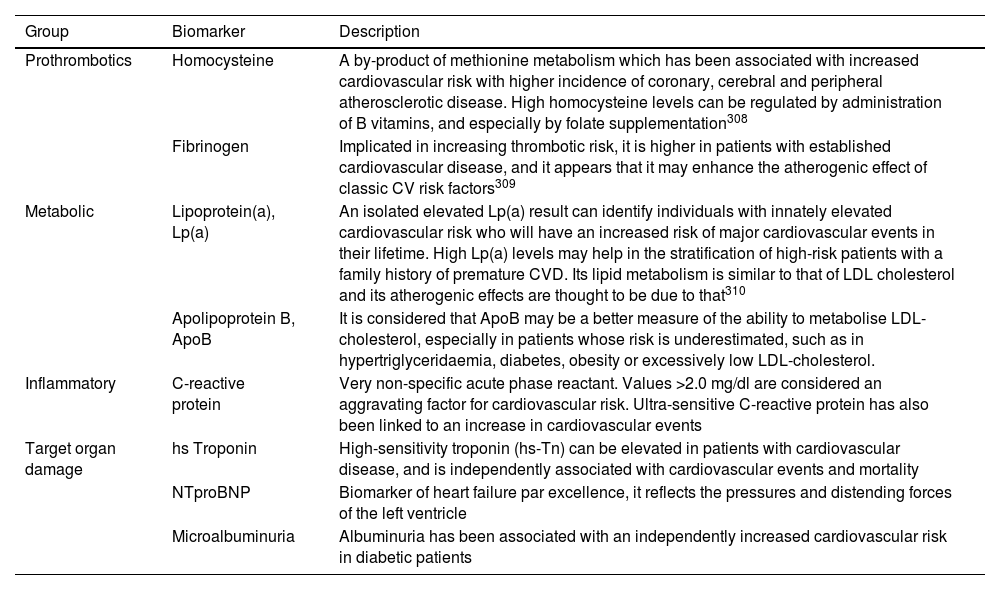

As for the determination of biomarkers, their routine use in cardiovascular risk assessment is not generally recommended. There are many different molecules present in the blood, alteration of which is associated with an increased incidence of cardiovascular events; the main ones are shown in Table 4.

Biomarkers associated with increased cardiovascular risk.

| Group | Biomarker | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Prothrombotics | Homocysteine | A by-product of methionine metabolism which has been associated with increased cardiovascular risk with higher incidence of coronary, cerebral and peripheral atherosclerotic disease. High homocysteine levels can be regulated by administration of B vitamins, and especially by folate supplementation308 |

| Fibrinogen | Implicated in increasing thrombotic risk, it is higher in patients with established cardiovascular disease, and it appears that it may enhance the atherogenic effect of classic CV risk factors309 | |

| Metabolic | Lipoprotein(a), Lp(a) | An isolated elevated Lp(a) result can identify individuals with innately elevated cardiovascular risk who will have an increased risk of major cardiovascular events in their lifetime. High Lp(a) levels may help in the stratification of high-risk patients with a family history of premature CVD. Its lipid metabolism is similar to that of LDL cholesterol and its atherogenic effects are thought to be due to that310 |

| Apolipoprotein B, ApoB | It is considered that ApoB may be a better measure of the ability to metabolise LDL-cholesterol, especially in patients whose risk is underestimated, such as in hypertriglyceridaemia, diabetes, obesity or excessively low LDL-cholesterol. | |

| Inflammatory | C-reactive protein | Very non-specific acute phase reactant. Values >2.0 mg/dl are considered an aggravating factor for cardiovascular risk. Ultra-sensitive C-reactive protein has also been linked to an increase in cardiovascular events |

| Target organ damage | hs Troponin | High-sensitivity troponin (hs-Tn) can be elevated in patients with cardiovascular disease, and is independently associated with cardiovascular events and mortality |

| NTproBNP | Biomarker of heart failure par excellence, it reflects the pressures and distending forces of the left ventricle | |

| Microalbuminuria | Albuminuria has been associated with an independently increased cardiovascular risk in diabetic patients |

With regard to endothelial dysfunction, we mention above that it is the first change to occur in atherosclerotic disease and in retrospective studies of patients with different inflammatory diseases, there is evidence of an association between these changes and the occurrence of cardiovascular events.97 Until a few years ago, the study of endothelial dysfunction required invasive tests or nuclear medicine scans to determine baseline coronary flow and flow after vasodilation, as an indicator of microcirculation and endothelial function status. Technological advances are enabling non-invasive measurement by CT scanning. Nevertheless, assessment of endothelial function is not indicated in cardiovascular risk assessment. Currently, the specificity, cost and risks associated with these tests mean that they are restricted to clinical use for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes for problems of myocardial ischaemia.98 A recent meta-analysis reported that patients with IBD have increased endothelial dysfunction and arterial stiffness, opening the door for future research to confirm their diagnostic value in preventing cardiovascular events and for supplementing cardiovascular risk stratification with these techniques in patients with IBD.64

Recommendation

- -

The routine use of imaging tests, biomarkers or coronary function tests is not recommended in the assessment of cardiovascular risk in patients with IBD.

- -

Some incidental findings of subclinical atherosclerotic disease, coronary calcium in particular, can be used to reclassify the patient’s overall cardiovascular risk.

In previous sections we have seen that, as in other immune-based inflammatory processes such as psoriasis, RA and systemic lupus erythematosus, cardiovascular risk is increased in IBD.99 It is well established that a chronic inflammatory process accelerates atherosclerosis and increases the number of cardiovascular events, both venous and arterial,100 with the increased risk being much more apparent in patients under the age of 50.37,99 Overall, cardiovascular risk will depend on the patient, the disease activity and the treatment given.101

From the point of view of the patient, it is not sufficiently clarified whether CVRF are more prevalent in those with IBD, as the data are discordant. Compared to the general population, different authors have reported the prevalence to be lower,102 similar24,103 or higher,48 particularly in patients under the age of 65. However, even if the rate of risk factors were higher, this would still not explain the almost two-fold increase in the risk of cardiovascular events.

Given that a chronic inflammatory process increases the likelihood of a cardiovascular event, logically, several clinical trials have attempted to assess whether drugs with the potential to control an inflammatory process reduce the risk of new cardiovascular events. The first study with positive results was CANTOS,104 which compared the effect of canakinumab, an IL-1β inhibitor, to placebo in patients with AMI and elevated high-sensitivity CRP (>2 mg/l). However, a subsequent trial with methotrexate (MTX) found no reduction in new cardiovascular events.105 Therefore, not all anti-inflammatory drugs reduce cardiovascular risk. The effect on IL-1β and IL-6 seems to be instrumental here. Positive studies with low-dose colchicine (COLCOT and LoDoCo2)106,107 have led to FDA approval of colchicine at a dose of 0.5 mg/day to reduce cardiovascular events in patients with established cardiovascular disease.

However, the setting treated in these clinical trials is clearly different from that of patients with IBD, as they included patients with cardiovascular events where the inflammatory burden is lower than in IBD. The data cannot therefore be extrapolated, but these studies show that controlling inflammatory activity could reduce cardiovascular risk.

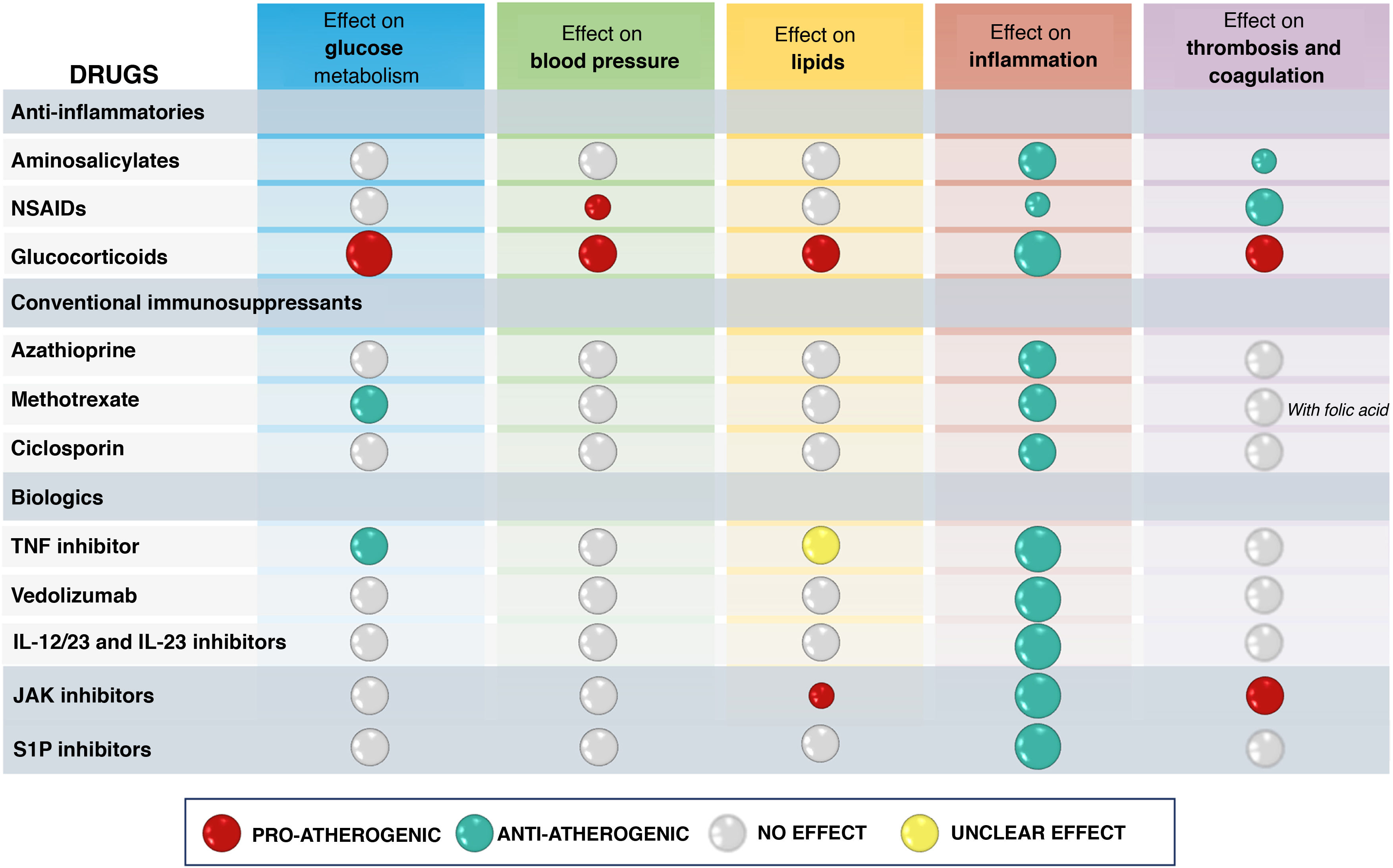

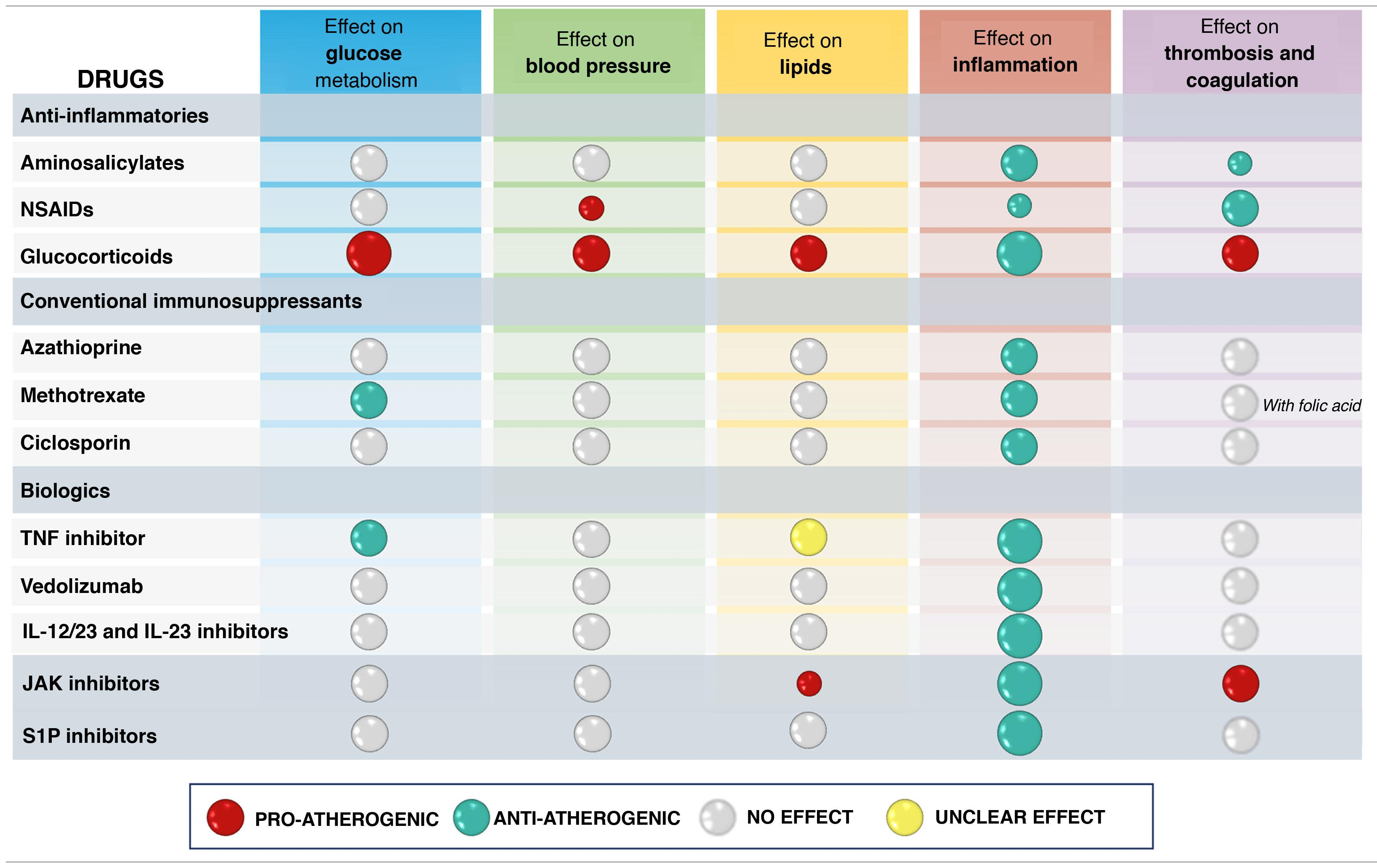

In addition to its effect on inflammatory burden, the overall net effect of a drug used for IBD treatment on cardiovascular risk will depend on its potential effects on classic CVRF such as HT, DM or dyslipidaemia, or its possible actions on coagulation or thrombosis101 (Table 5). In this point we review the available data on the different treatments used for IBD management with respect to cardiovascular risk. It is important to note that there are a number of limitations to generating evidence on this effect. First of all, studies have to include a large number of patients, as cardiovascular events are rare in the IBD population. This often requires the use of registries for access to information on a large number of patients, but it is common for the information not to be sufficiently complete. In this type of study it is particularly important to adjust the baseline risk of the populations being compared (with or without a given drug) and in the existing publications this has not always been done, especially with regard to the extent of IBD activity, usually due to lack of information in the databases.

Theoretically speaking, it is difficult to predict the effect of these drugs on cardiovascular risk. While they have a potentially beneficial antiplatelet action (at least sulfasalazine [SFS]), they may have a neutral effect on endothelial function108 or they may increase arterial stiffness.109 SFS can also increase total and LDL cholesterol levels, at least in association with prednisone, hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) and MTX.110 Despite these possible negative effects on cardiovascular risk, a case-control study found that SFS may reduce cardiovascular risk in RA patients without prior exposure to HCQ, MTX or SFS.111

In patients with IBD there are two case-control studies based on national registries. In the Danish study,70 which included 28,833 patients with 1,175 episodes of CHD, the group treated with aminosalicylates had a lower incidence than the untreated group. The UK study112 also found no increase in CV risk.

CorticosteroidsIt is well known that corticosteroids increase cardiovascular risk by increasing the likelihood of having a known risk factor, even if they adequately control the inflammatory activity of the patient’s underlying disease.

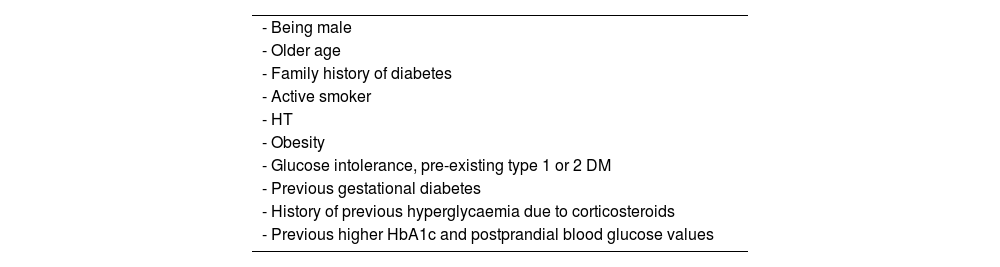

First, they increase the risk of developing HT at rates ranging from 17% to 73% of treated patients with different diseases113,114; this effect is seen at doses above 7.5 mg/day, with no clear dose/effect relationship beyond that dose.113 The risk of hyperglycaemia and DM with these drugs is also well known, occurring in 32.3% and 18.6% respectively115 (Table 6).

Predisposing factors for the development of hyperglycaemia or diabetes with steroid therapy.

| - Being male |

| - Older age |

| - Family history of diabetes |

| - Active smoker |

| - HT |

| - Obesity |

| - Glucose intolerance, pre-existing type 1 or 2 DM |

| - Previous gestational diabetes |

| - History of previous hyperglycaemia due to corticosteroids |

| - Previous higher HbA1c and postprandial blood glucose values |

DM: diabetes mellitus; HbA1c: glycated haemoglobin; HT: hypertension.

Other effects that contribute to the increased cardiovascular risk of these drugs are weight gain, sodium retention with subsequent oedema and hyperlipidaemia.116,117 The lipodystrophy they cause goes beyond an aesthetic change, as it is associated with hypertension, hyperglycaemia and hyperlipidaemia,118,119 so when these changes occur, these risk factors should be investigated and treated.

Corticosteroids also induce a state of hypercoagulability (increased fibrinogen levels and decreased tissue plasminogen activator [tPA]),120 so an increased risk of VTE is to be expected. In fact, this risk is well known both in general121,122 and in the different diseases in which these drugs are used.123–129 In IBD, a published meta-analysis including eight observational studies with nearly 60,000 patients with IBD and 3,260 thromboembolic events found an increased risk (OR: 2.2) with corticosteroid exposure compared to patients not exposed to corticosteroids.130 Studies in specific situations such as inpatients131 or postoperative patients132 show similar results. The biggest criticism of these studies is the lack of adjustment for disease severity, with corticosteroid exposure being a marker of severity and thus increased risk of VTE.133 However, comparing corticosteroids to TNF inhibitors, which may also be associated with greater severity, the risk of VTE is reduced five-fold with TNF inhibitors (OR: 0.267, 0.16–0.67, p < 0.005).130,134,135 There is also a clear association between dose and higher risk of VTE, with the risk increasing by a factor of 10 with prednisone doses above 30 mg/day,136 while at low doses (<5 mg/day), although less pronounced, it is still increased. The risk is highest at the start of treatment and decreases thereafter, but remains modestly increased even after treatment is stopped.114,136

Age is an important factor to take into account, as not only are older patients less likely to respond to corticosteroids but, as found in a retrospective multicentre study which included patients with UC, the risk of VTE is also substantially higher (7.2% vs 0.5%).137

Corticosteroids have been associated with an increased risk of arterial thrombosis in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMID).138 However, not all studies concur139 and, once again, in most cases there is no adjustment for disease severity. In a prospective study in RA, the increased risk of cardiovascular events with corticosteroid exposure disappeared after adjusting for disease activity.140 Large retrospective registry-based studies,141,142 which included patients with IBD, showed that the risk of CVD increased with corticosteroid exposure; the risk was twice as high at a dose of 5 mg/day of prednisone compared to unexposed patients, and increased six-fold if the dose was above 25 mg/day. Once again, with these drugs there is no dose that does not involve some risk.

From the studies that only include patients with IBD, we highlight two. The first,71 after adjusting for CVRF, found an increased rate of AMI and heart failure in patients on steroid therapy compared to controls. The second study143 is a retrospective cohort where they found a higher mortality rate in patients with CD with prolonged exposure to corticosteroids (>3,000 mg prednisone or >600 mg budesonide) compared to TNF inhibitors, and higher CVD rates in patients with CD, but not in patients with UC.

Either way, in the absence of optimally designed studies in IBD, the published consensus on cardiovascular disease and IMID59 advises avoiding prolonged treatment with corticosteroids, aiming to withdraw them as soon as possible and constantly reassessing the reasons for the patient to continue taking them.

Recommendations

- -

Corticosteroids increase the risk of venous thrombosis, even at low doses, so it is recommended to monitor for this complication during treatment and even for 2–3 mo after withdrawal.

- -

Corticosteroids promote both the development of CV risk factors and CV disease and the benefits and risks should therefore be weighed up before their use in patients with CVD. If they are indispensable, it is advisable to discontinue them as soon as possible and to avoid prolonged use.

There are experimental data in murine models of atherosclerosis suggesting that these drugs may have a protective role.144 However, there are not many clinical studies demonstrating their possible protective role on CVD. In the Danish National Patient Register study, which compared a large volume of patients with IBD versus controls, the rate of CHD tended to be lower with thiopurines, although the difference was not statistically significant.70 However, a more recent analysis of the same Danish registry, covering the period from 2005 to 2018, did find that thiopurines had a protective effect on arterial events in general, and on the occurrence of CHD or cerebrovascular disease in particular.145 In contrast, in a French national study involving 177,827 patients with IBD comparing the risk of arterial events in exposed and unexposed patients, azathioprine had no protective effect.146 However, in a recent study based on the same French database,147 thiopurines were associated with a reduced risk of recurrence of arterial events in patients with IBD (HR: 0.76, 95% CI: 0.66–0.88), so they may have a protective effect in higher risk patients.

MethotrexateEvidence on the effect of methotrexate (MTX) on cardiovascular risk in patients with IBD is limited and the data are almost entirely from other IMID, mainly RA and psoriasis. Firstly, MTX has potential beneficial effects on classic CVRF, as it can reduce BP.148 It has a beneficial effect on the lipid profile, with an increase in HDL-cholesterol function, a reduction in foam cell formation and a decrease in atherogenic lipoproteins.149,150 It may also reduce the risk of type 2 DM by up to 19%151 and, in patients with established type 2 DM, it may reduce glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c).150

However, it is well known that MTX interferes with folic acid metabolism, leading to the development of hyperhomocysteinaemia, which increases the risk of both atherosclerotic CVD and VTE. Nonetheless, it is common practice to use MTX in combination with folic acid, so their combined use lowers homocysteine concentrations,149 thus avoiding the negative effect on cardiovascular risk.

The net effect of MTX on cardiovascular risk has been studied most in clinical practice in RA, with several meta-analyses having been published. The most recent,152 which includes 10 studies with a total of 195,416 patients, concludes that MTX reduces the risk of CVD by 20% (RR: 0.798; 95% CI: 0.726–0.876; p = 0.001; I2 = 27.9%). This effect has been corroborated in a recent prospective study,153 where disease activity is adjusted for, with high doses (>15 mg/week) being more beneficial. MTX has also been shown to significantly reduce CVD mortality rates in RA.154 It remains unclear whether or not the combination of MTX and biologic drugs increases the protective effect, as there are studies with discordant results.153,155

CiclosporinCiclosporin can induce hypertension early on in treatment.156 This has to be taken into account if prescribing it in patients with severe UC, as almost all patients will be treated concomitantly with corticosteroids, which as mentioned above, can also produce the same effect. There is no specific information on the cardiovascular risk associated with long-term use of ciclosporin in patients with IBD. Prolonged use in different disease groups is known to be associated with the development of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis, hyperlipidaemia and an increased risk of atherosclerosis.157

Recommendation

- -

In patients at CV risk being assessed for treatment with ciclosporin, it is recommended that other treatment options be considered first, as ciclosporin use is associated from the start with an increased risk of hypertension and, long-term, with hyperlipidaemia and an increased risk of atherosclerosis.

Information on the effects of tacrolimus on cardiovascular risk factors comes mostly from studies in transplant patients, with no specific data available in the subgroup of patients with IBD.158 Extrapolating from studies in the transplant patient setting, tacrolimus is known to produce similar effects to ciclosporin (both are calcineurin inhibitors), potentially leading to the development of hypertension, although to a lesser extent than ciclosporin,159 and causing hyperlipidaemia. These aspects therefore have to be taken into account when prescribing this treatment.

Recommendation

- -

In patients at CV risk being assessed for tacrolimus treatment, it is recommended that other options be considered, as tacrolimus is associated from early on in treatment with an increased risk of hypertension (although somewhat less than ciclosporin) and, long-term, with hyperlipidaemia and an increased risk of atherosclerosis.

The effect of TNF inhibitors on cardiovascular risk depends primarily on their ability to control inflammatory activity, as their influence on classic CVRF is weak or even negative, as we discuss below.

With regard to carbohydrate metabolism, TNF inhibitors generally decrease insulin resistance160–162 and HbA1c160 and improve beta-cell function. TNF-α increases insulin resistance as well as the inflammatory activity of the disease itself162; therefore, it is logical to assume that the use of TNF inhibitors would have a beneficial effect. There are published cases of both type 1 and type 2 DM with improved control of DM following the use of these drugs,163 in addition to the beneficial effect of golimumab reported in new-onset type 1 DM.164

These drugs have been associated with weight gain,165–169 although it is difficult to know whether this is a direct effect or due to the control of inflammatory activity and improvement in nutritional status. The most important study in this respect is that by Winter et al.,170 which included 851 patients from four Danish databases of patients starting treatment with TNF inhibitors. Fewer than 10% of patients achieved weight gain of more than 10% from baseline, and they were mainly patients with low baseline weight. It is most likely the same would happen regardless of the biologic drug used if control was achieved of the inflammatory activity of the underlying disease.171

Lastly, TNF inhibitors have been linked to changes in lipid profile. There is also a recent meta-analysis in IBD describing the effect of various groups of drugs used in the management of IBD on lipid metabolism.116 In this study they find that corticosteroids and tofacitinib produce a significant elevation of cholesterol levels, but TNF inhibitors do not. Other studies have found elevation of less than 10% in total cholesterol, HDL and triglycerides,171 so the actual influence it could have on cardiovascular risk seems limited.

TNF inhibitors may also improve markers of atherosclerosis and risk of future cardiovascular events; examples are endothelial dysfunction172 or arterial stiffness,173 although results on their influence on carotid intima-media thickness are inconsistent.174–178

With regard to venous thromboembolic events, TNF inhibitors resolve predisposing coagulation disorders to a greater extent than other drugs such as vedolizumab or thiopurines.179 A meta-analysis of eight observational studies found that TNF inhibitors reduced the risk of VTE almost five-fold (OR: 0.267, 95% CI: 0.106–0.674, p = 0.005).130 However, perhaps the most important study, both in terms of the number of patients included (5,173 patients with IBD starting TNF inhibitors versus 16,498 controls) and the initial adjustment of the variables included, is that of Desai et al.,180 despite its retrospective design. The variable of interest is hospital admission for VTE, with episodes managed on an outpatient basis excluded. TNF inhibitors were not a protective factor, although the trend is clear (HR: 0.78, 95% CI: 0.6–1.02). However, in patients with CD (HR: 0.62; 95% CI: 0.44–0.86) or in those under the age of 45 (HR: 0.55; 95% CI: 0.34–0.87), TNF inhibitors do reduce the risk of VTE. A recent meta-analysis comparing them with corticosteroids shows a three-fold lower risk of VTE (PMID: 37952112).

In IBD, there is a much smaller amount of data than in other IMID on the reduction in the risk of arterial events (CHD, peripheral artery disease or ischaemic stroke) associated with the use of TNF inhibitors. The first notable study is that of Lewis et al.,143 which compares mortality rates and CVD in patients with prolonged exposure to corticosteroids with respect to the use of TNF inhibitors in two American databases. A reduction in the mortality rate (OR: 0.78, 0.65–0.93) and CVD (OR: 0.68, 0.55–0.85) was only found in patients with CD, probably because the number of patients with UC was substantially smaller. The most prominent study is the one by Kirchgesner et al.,146 which analyses the French healthcare database including 177,827 patients with IBD, comparing exposed and unexposed patients. They find a 21% reduction in the risk of arterial events with TNF inhibitors (HR: 0.79, 95% CI: 0.4–0.72). A later study147 based on the same database, although in a different time period, analysed the risk of recurrence of arterial events in patients who had already had a previous episode. In this case, both TNF inhibitors (HR: 0.75; 95% CI: 0.63–0.9) and thiopurines (HR: 0.76; 95% CI: 0.66–0.88) were associated with a lower risk of recurrence. There are several meta-analyses of other IMID with similar results; of these, the one by Fumery et al.181 stands out because, in addition to patients with spondyloarthritis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and RA, it includes patients with IBD. The risk reduction for arterial events associated with biologics was 30% overall (OR: 0.7, 0.59–0.82); this rate only held up when considering studies adjusted for disease severity. It is important to highlight two aspects of the studies in rheumatic diseases; firstly, that the benefit is seen in patients who respond to TNF inhibitors182,183 and secondly, that the longer the duration of exposure the greater the risk reduction.184 However, a recent network meta-analysis of 40 studies (seven of them in patients with IBD), mostly clinical trials, found an association between CVD and TNF inhibitors (OR: 2.49; 1.14–5.62) similar to JAK inhibitors and anti-IL12/23.185 This was an association, and the study did not analyse outcomes by CV risk or IBD activity.

Lastly, it is very important to remember that the use of TNF inhibitors has been associated with exacerbation of heart failure, so they are not recommended in patients with heart failure and NYHA functional class III–IV.186

Recommendations

- -

There are conflicting results on the CV risk of TNF inhibitors. However, if they are necessary for the treatment of IBD, we recommend their use regardless of baseline CV risk or previous CVD.

- -

TNF inhibitors have been associated with worsening heart failure and are therefore contraindicated in patients with NYHA functional class III–IV.

There are few data on the potential effects of vedolizumab on cardiovascular risk. Analysis of the Truven MarketScan database (published in abstract form only),187 including 597 patients with CD treated with vedolizumab and 16,055 with TNF inhibitors, found a significant increase in cardiovascular events (IRR: 2.06, 1.37–3.09) with vedolizumab. They also found an increased risk of pulmonary embolism (IRR: 3.01, 1.11–8.18) and deep vein thrombosis (IRR: 2.67, 1.32–5.41) in patients treated with vedolizumab. However, it should be noted that there was no adjustment for the populations studied, with marked differences between them, such as the greater use of corticosteroids in the vedolizumab group (78.8% vs 48.9%); this is important given the known increased risk of venous thrombosis with the use of corticosteroids. In the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) adverse event reports database, there is no alert of a possible association with venous thrombosis in patients receiving vedolizumab therapy. However, there is a warning of a possible association with stroke compared to that found with TNF inhibitors, although it is only a pointer to a potential association (which serves as a basis for long-term observational studies), as it is based on voluntary reports.188 Safety reviews of the drug have found no increase in cardiovascular events.189,190 In view of the above, there are no solid data to support this drug being associated with an increased cardiovascular risk.

UstekinumabTheoretically, blocking IL-12 in experimental animals leads to decreased atherogenesis and greater stabilisation of the atheroma plaque.191 The IL-23/IL-17 axis has opposing effects; on the one hand it blocks different mediators involved in the atherogenesis process (IL-6, GM-CSF and several chemokines) and on the other, it activates the production of type I collagen by muscle cells, contributing to plaque stabilisation.192 We know that IL-23 and IL-22 play a role in preventing the expansion of the pro-atherogenic microbiota; indeed, certain IL-23-deficient murine models show accelerated atherosclerosis, which can be blocked by microbiota suppression.193 Studies with measurement of carotid intima or arterial stiffness have failed to clarify these conflicting effects, as the results are not uniform.194,195 However, there are data supporting the anti-atherogenic potential of ustekinumab, such as a small clinical trial of 43 patients showing a reduction in aortic vascular inflammation with PET/CT196 in patients treated with ustekinumab versus placebo. A study with non-invasive CT coronary angiography before and after treatment with various biologic drugs in patients with psoriasis shows a reduction in atheromatous plaques similar to that obtained with TNF inhibitors, but significantly lower than that found with anti-IL-17.197

The clinical data on the influence of these drugs on cardiovascular risk derive mainly from dermatology patients, in whom there is the most accumulated evidence. The first published meta-analysis, which included data on briakinumab (a monoclonal antibody against IL-12 and IL-23), a drug not ultimately approved, found no higher risk of CVD in patients treated with anti-IL-12/23 drugs than with TNF inhibitors198 or placebo. However, a later meta-analysis199 did find an increased risk of CVD with these drugs (OR: 4.23; 95% CI: 1.07–16.7) compared to placebo. However, this study has been widely criticised200 for methodological issues, such as the method of analysis used (Peto odds ratio), the small number of CVD (only 10 cases), the short follow-up and the lack of adjustment for losses. All of the above significantly limits the weight that can be given to such a meta-analysis. Subsequently, another more recently published meta-analysis did not find an increase in CVD with TNF inhibitors, anti-IL-17 drugs or ustekinumab. We should not forget that clinical trials are primarily designed to assess efficacy, so rare adverse effects may go undetected; not to mention that CVD is associated with certain characteristics (such as age and comorbidity), which are often an exclusion criterion for clinical trials. For this reason, registries (especially prospective registries) are more likely to find an association. The prospective PSOLAR registry, which includes the largest number of patients (12,093 patients; 40,388 patient-years), did not find an association between CVD and ustekinumab use,201,202 and nor did the American,203 German,204 Danish205 or British-Irish206 registries.

Another recent study,207 also object of debate, aimed to assess whether ustekinumab treatment would have the above-mentioned effect of destabilising the atheroma plaque, such that it might induce early CVD in high-risk patients. The study included 9,290 patients exposed to ustekinumab (1,110 with CD) from the French national health system database, 179 of whom had severe CVD requiring hospital admission (stroke or acute coronary syndrome). The authors looked for an association between the introduction of ustekinumab and CVD, finding an increased risk only in patients at high cardiovascular risk (OR: 4.17, 95% CI: 1.19–14.59) and not among those at low risk. The main limitation of the study, apart from the arbitrary time limits, is the lack of adjustment for confounding factors, the most important of which are concomitant medication (for example, corticosteroids) and disease activity (both more likely at the time of initiation of drug treatment), which per se increase cardiovascular risk and could be triggers for CVD, which may not be directly related to the drug.191 Lastly, we should mention the recent network meta-analysis including 40 controlled studies (36 randomised) with different drugs in IMID diseases, where IL-12/23 inhibitors are associated with an increased risk of CVD similar to TNF inhibitors or JAK inhibitors.185 However, according to the study’s conclusion, the choice of drug in IBD should be driven more by disease characteristics than by cardiovascular risk, since adequate control of the underlying disease is the main determinant of early or accelerated CVD.208

JAK inhibitors: tofacitinib and othersThe influence of tofacitinib on CVRF is centred on the elevation of serum lipid levels,116,117,209 mainly at a dose of 10 mg/12 h, which affects total cholesterol as well as HDL and LDL, leaving the LDL/HDL ratio unchanged. The elevations are modest (for example, 16 mg/dl average increase in LDL-cholesterol during the maintenance phase of treatment) and respond well to statin therapy.210

Experimentally, both in murine models211 and in human endothelial cells,212 it has an anti-atherogenic effect by inhibiting several of the mediators involved in this process, so the mechanism by which it increases cardiovascular risk in at-risk patients is not fully understood.

Starting with the risk of VTE, we have to mention the ORAL Surveillance study, which prompted warnings from the FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA). This study started in 2014 and includes patients over 50 years of age with moderate or severe RA, MTX failure and at least one cardiovascular risk factor. Patients are randomised to three groups, tofacitinib 5 mg/12 h, tofacitinib 10 mg/12 h or a TNF inhibitor, with more than 1,400 patients included in each arm of the trial. In February 2019, an interim analysis was performed in which differences were found in rates of mortality (HR: 3.28; 95% CI: 1.55–6.95) and pulmonary embolism (HR: 5.96; 95% CI: 1.75–20.33) between the group of patients treated with tofacitinib 10 mg/12 h and those treated with TNF inhibitors; these differences were only seen in patients with risk factors for VTE.47 However, although the RR may seem high, incidence rates are low. For tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg/12 h and TNF inhibitors, the incidence rates for pulmonary embolism were 0.27, 0.5 and 0.09 patient-years and for DVT, 0.3, 0.38 and 0.18 patient-years respectively. The main risk factors for VTE found in this study for all treatment groups were: history of previous VTE (HR: 7; 2.46–20.2); concomitant use of corticosteroids (HR: 3), oral contraceptives (HR: 3.56) or antidepressants (HR: 2.94); HT (HR: 2.57); being male (HR: 2.18); BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (HR: 2.97); and age ≥65 (HR: 2).213

However, these data are not corroborated in published meta-analyses214,215 which include clinical trials in the different IMID. It is true that follow-up time is limited and the CVRF population is under-represented.

In clinical practice series and registries, no differences have been found between patients treated with tofacitinib and control groups (routinely treated with TNF inhibitors) in either rheumatology patients or patients with UC.216,217 In the clinical trial programme in patients with UC, only five cases of pulmonary embolism and one case of DVT were found in the open extension phase,218 giving incidence rates of 0.28 (0.09–0.65) and 0.06 (0.00–0.31) respectively. All but one patient had predisposing factors.

With the other JAK inhibitors tested in IBD, like tofacitinib, no increase in VTE has been found with respect to controls, and the incidence rates are all similar.219 We do not know whether the increased selectivity of these new JAK inhibitors leads to a lower risk of VTE, but there are reports for selective JAK inhibitors in the FDA pharmacovigilance database which suggest this should be investigated.220,221 The EMA has conducted a comprehensive analysis of the potential extrapolation of the ORAL Surveillance results to indications other than RA, to other patient populations treated with this class of drugs and to other JAK inhibitors. To sum up a very comprehensive review document by the EMA,222 it appears that the increased risk of VTE and major cardiovascular events detected in that study was a class effect, with insufficient objective data to limit the cardiovascular side effects identified in ORAL Surveillance to tofacitinib alone. Nevertheless, preliminary results from an observational study (B023) with another JAK inhibitor (baricitinib) also suggest an increased risk of major cardiovascular events and VTE in RA patients treated with baricitinib compared to those treated with TNF inhibitors.223 The data from ORAL Surveillance (and preliminary data from the B023 study) on the risk of VTE have therefore been generalised by the EMA for all JAK inhibitor drugs. The use of anticoagulation appears to be effective in preventing VTE episodes in patients treated with JAK inhibitors.224 There is no definite indication for when anticoagulants should be used, but it is probably reasonable to prescribe them for patients who have several risk factors.

For the risk of arterial events, we refer back to the ORAL Surveillance study225 which, with a non-inferiority design, sets the upper limit of the HR confidence interval at less than 1.8, to consider an adverse effect rate equivalent to TNF inhibitors. In the specific case of CVD, this threshold is exceeded and CVD is considered to be more common in groups treated with tofacitinib than in the TNF-inhibitor groups (OR: 1.33; 95% CI: 0.91–1.94). The CVD incidence rates for the tofacitinib 5 and 10 mg/12 h and the TNF-inhibitor groups is 0.91, 1.05 and 0.79 per 100 patient-years respectively. Expressed in terms of the number of patients needed to treat per year for CVD to occur, the figure would be 567 for the 5 mg/12 h dose and 319 for the 10 mg/12 h dose.225 Sub-analyses published subsequently have attempted to identify factors that may identify sub-populations in this study with an increased risk of CVD with tofacitinib compared to TNF inhibitors.226,227 The most important determinant is whether or not the patient has had a previous episode of CVD. In this subgroup of patients, the incidence of a new CVD episode was 8.3% and 7.7% for the 5 and 10 mg/12 h doses of tofacitinib respectively, compared to an incidence of 4.2% with TNF inhibitors (HR: 1.94; 95% CI: 0.95–4.14). However, in patients without previous CVD episodes, the incidence of new episodes was very similar in all three groups (2.4, 2.8 and 2.3% respectively).226 It is true that this is a sub-analysis and that the statistical power may not be sufficient to detect differences between patients without previous CVD episodes, but in any event the risk would be very low. Another sub-analysis of the ORAL Surveillance study analyses the weight of different risk factors and concludes that age ≥65 and smoking (current or past) independently lead to a higher risk. When one of these two factors is present, there is an increased risk of CVD, VTE, cancer and death. However, in patients without either of these two factors, the incidence of CVD and VTE is similar to that found with TNF inhibitors.227 One area of debate is the imprecise definition of former smoker. In this study, the majority of patients with a history of smoking had smoked for more than 10 years (96.2% and 98.4% in the tofacitinib and TNF-inhibitor groups respectively) with a CVD risk similar to that of active smokers, although over 60% of them had stopped smoking more than 10 years previously. Lastly, it should be noted that the degree of disease control could be a determinant of CV risk, as a new sub-analysis of ORAL Surveillance found no differences in CVD between groups in patients with fully controlled disease, but this was not the case in those with partial control.208

Again, published meta-analyses,214,228 observational studies in UC,229 review of patients in the UC programme218,230,231 and observational studies from registries in both IMID271,232–235 and UC236–239 do not find a higher incidence of CVD in patients treated with tofacitinib compared to other treatments. The STAT-RA study is interesting because it replicates the ORAL Surveillance findings, and in some ways may explain this apparent discordance. This study included 12,852 RA patients treated with tofacitinib from three American databases, and compared them to those treated with TNF inhibitors with an appropriate propensity score adjustment. No differences in CVD (HR: 1.01, 0.83–1.23) were found between the two groups, although selecting patients with ORAL Surveillance inclusion criteria, there was a non-significant trend in the group of patients treated with tofacitinib (HR: 1.33, 0.91–1.94).

In patients with UC the baseline CV risk is generally low; in the OCTAVE programme 80% of patients had a low CVD risk. In contrast, this figure is clearly lower in RA trials (21% in ORAL Surveillance and 54% in the initial clinical trials)240 and in psoriatic arthritis (63%).241 This may partly explain why no increase in CVD or VTE is found in IBD studies. In IBD, attempts have also been made to identify patients at increased risk of CVD on JAK treatment. Age ≥65 is clearly a risk factor for CVD in a sub-analysis of UC trials with tofacitinib242 when compared to the younger population, although this is likely to be true for any other drug, reflecting a higher overall incidence in this population subgroup. Moreover, the RR is not very high (IR: 1.06; 0.13–3.61) and therefore does not have a high discriminating power. Another more interesting approach is that of Schreiber et al.,231 who calculated the baseline CV risk of patients included in the OCTAVE studies using Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) and relating it to the events found. Patients with a high (>20% at 10 years) or intermediate (≥7.5% and <20%) CV risk had more CVD (IR: 1.81, 0.05–10.07; IR: 1.54, 0.42–3.95, respectively) than those with no or borderline baseline risk, where the number of events was minimal (2/901). Therefore, the calculation of baseline risk could be useful for identifying patients at increased risk of CVD, and also with these drugs. The data with the two new JAK with indication in IBD, filgotinib and upadacitinib, are similar. In the absence of a trial similar to ORAL Surveillance, no increased incidence of CVD has been found among IMID patients treated with these drugs compared to different comparators, either placebo, TNF inhibitors or MTX.243–246 Corresponding IBD programmes have also not found an increased incidence of CVD.247–249 Despite all these data, the recent network meta-analysis discussed above, which includes clinical trials of several IMID indications, does find an increased CV risk (OR: 2.64; 1.26–5.99) but no difference with TNF inhibitors or IL-12/23.185

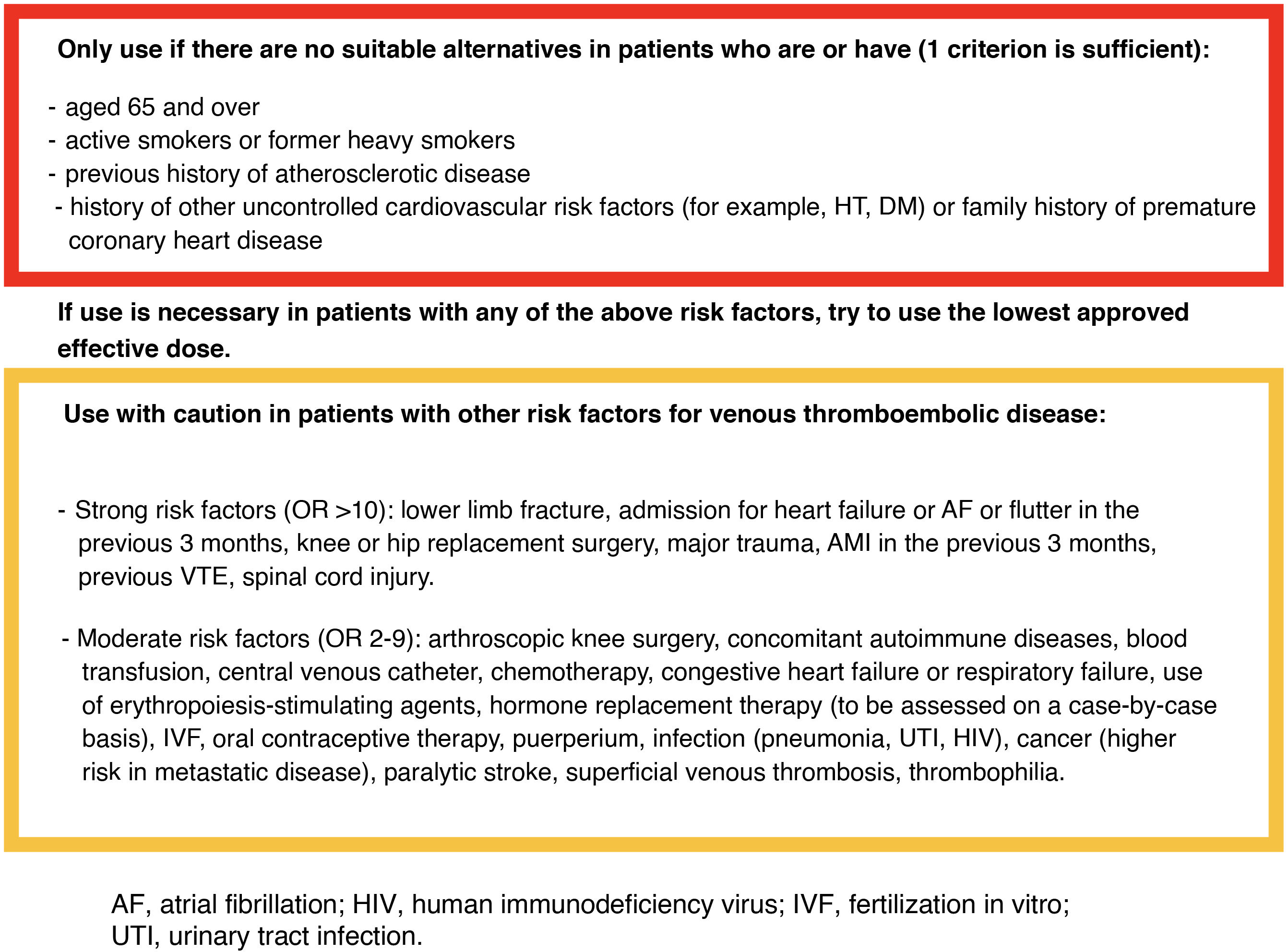

However, the EMA has restricted (from a cardiovascular point of view) the use of JAK inhibitors to situations where there are no suitable alternatives in patients aged 65 or over, patients at increased risk of serious cardiovascular problems (such as AMI or stroke), patients with a history of atherosclerotic disease, and active smokers or former heavy smokers of long duration. They should also be used with caution in patients who have risk factors other than those described above for developing VTE.223

We believe that it could be useful in clinical practice to have a baseline checklist for CVRF and possible limitations of the use of these drugs in patients with IBD which can be updated periodically and would certainly provide greater safety when using this type of drug.

We have included an example of a checklist (Fig. 3) to help us simply, quickly and reliably identify patients in whom this type of drug can be safely used.

Checklist on cardiovascular risk and venous thromboembolic disease in patients with IBD to assess the use of JAK inhibitor drugs (adapted from EMA recommendations and thromboembolic disease management guidelines).7,223,225

Recommendations

- -

JAK inhibitors increase CV risk in patients aged over 65 with CV risk factors, particularly in the case of previous CVD episodes or smoking, whether current or past if it was of long duration (10 or more years). The recommendation is therefore to avoid JAK inhibitors in these patients if other therapeutic options are available.

- -

It is also recommended not to use them in the presence of risk factors for venous thromboembolism unless there are no other alternatives. On the basis of current data, it is not possible to establish differences in risk between the different JAK inhibitors.

The first representative of this group of drugs was fingolimod, which caused cardiac conduction disturbances as a cardiovascular adverse effect. The frequency of symptomatic bradycardia in multiple sclerosis clinical trials was 0.6% for the lowest dose and 2.1% for the high dose.250 Second-degree AV block occurred in 1% of patients. In most cases, these abnormalities did not lead to withdrawal of the drug.

There are five S1P receptors, with variable distribution in different tissues; specifically in the heart, S1PR1, S1PR2 and S1PR3 are expressed. A more selective inhibitor (fingolimod is not selective) could be associated with a lower rate of adverse effects in general and cardiovascular effects in particular.33 Ozanimod is a selective inhibitor of the S1PR1 and S1PR5 receptors approved by the EMA for the treatment of UC. The rate of conduction disturbances appears to be lower than that found with fingolimod. In the meta-analysis of trials in multiple sclerosis, ozanimod is not associated with the development of bradycardia, but is associated with the development of HT.251 However, despite that, it is not associated with an increased risk of CVD. In the phase III trial, with 1,012 patients included, only five had bradycardia during the induction period and there were no cases of 2nd or 3rd degree heart block.252 In the same study there were only two cases of hypertensive crises, which did not lead to withdrawal of treatment. In the phase II trial in CD, the decrease in heart rate was very slight (0.7 bpm) and transient, returning to baseline heart rate at 6 h.253 The recently published phase III extension study in UC with a three-year follow-up254 reported a single case of bradycardia at the start of treatment (0.2/100 patient-years), a late case of complete AV block, which in principle was unrelated to the drug, and 12.2% of patients with HT (3.9/100 patient-years).

Etrasimod is a modulator of the S1P1, S1P4 and S1P5 receptors, with two phase III trials in UC including 289 and 238 patients. In these trials nine patients developed bradycardia (seven asymptomatic) on the first two days of treatment and on the first day three developed AV block (two first degree and one second degree) which was asymptomatic and did not require treatment.255

When starting treatment with these drugs, in particular with ozanimod, BP monitoring is advised weekly in patients with previous HT, ideally by the patients themselves, and in all cases at three months and then every six months.256 For conduction disorders, monitoring during the first six hours after dosing is advised in patients with a baseline heart rate below 55 bpm, a history of AMI, CHF or Mobitz type I second-degree AV block (type II and third-degree block are contraindications to treatment).256 In these cases, an ECG is performed at baseline and six hours, in addition to hourly BP and pulse measurements.

IL-23 inhibitorsThe role of IL-23 in experimental models of atherosclerosis is not fully understood, as data are inconsistent. It is true that in a murine model, an acceleration of atherosclerotic plaque has been found in mice deficient for the p19 subunit, but the majority of studies have failed to identify any effect related to p19 on plaque size or content.191 Elevated IL-23 levels have been associated with a higher mortality rate in patients with carotid atherosclerosis.257 In clinical practice, these drugs have an excellent safety profile and no increased risk of CVD has been observed in studies in IBD258,259 or psoriasis,260–262 where there is greater experience. In the network meta-analysis discussed above, IL-23 inhibitors did not increase CV risk, in contrast to TNF inhibitors, JAK inhibitors and ustekinumab.185

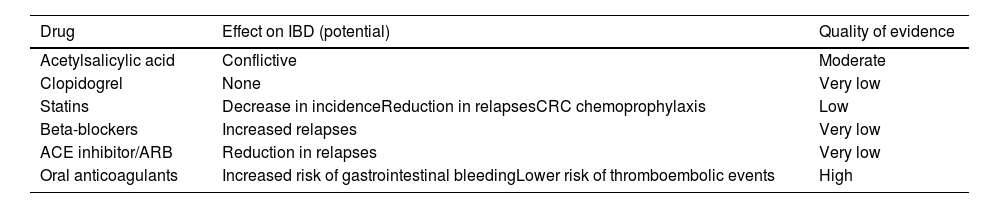

How can the medication we use to manage cardiovascular disease affect inflammatory bowel disease?The prevalence of IBD in patients over the age of 65 is increasing, with this age group currently accounting for 25–35% of all patients with IBD.263 The increase is due, on the one hand, to the rise in new diagnoses among over-65s (15–23% of new diagnoses at present263,264) and, on the other, to the ageing of patients with a chronic disease with a low mortality rate.265 We are therefore going to see more and more older patients with IBD in our practices, and it is estimated that by 2030 the prevalence of IBD in over-65s will be higher than in the 15–65 age group.266

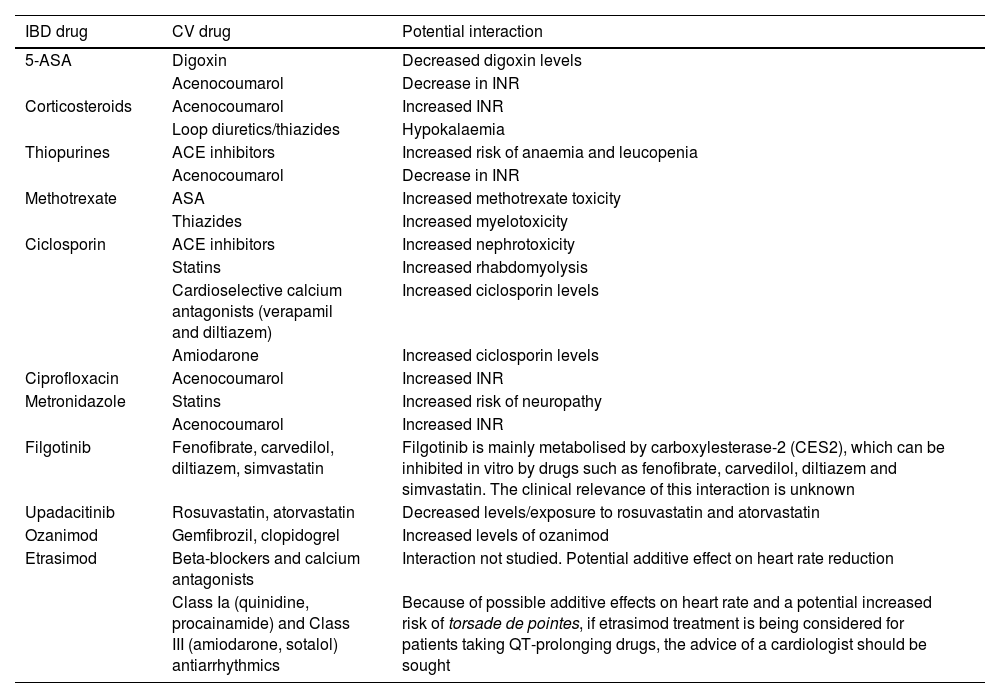

The particular characteristics of IBD management in the population over 65 include the need to pay special attention to comorbidities, frailty, cognitive impairment and polymedication. A recent study found that patients with IBD over 65 were taking an average of nine drugs, many of them used to treat CVD, 40% of which had potential interactions with drugs used to treat IBD267,268 (Table 7).

Potential interactions between drugs used in the management of patients with cardiovascular disease and drugs used in the treatment of IBD.

| IBD drug | CV drug | Potential interaction |

|---|---|---|

| 5-ASA | Digoxin | Decreased digoxin levels |

| Acenocoumarol | Decrease in INR | |

| Corticosteroids | Acenocoumarol | Increased INR |

| Loop diuretics/thiazides | Hypokalaemia | |

| Thiopurines | ACE inhibitors | Increased risk of anaemia and leucopenia |

| Acenocoumarol | Decrease in INR | |

| Methotrexate | ASA | Increased methotrexate toxicity |

| Thiazides | Increased myelotoxicity | |

| Ciclosporin | ACE inhibitors | Increased nephrotoxicity |

| Statins | Increased rhabdomyolysis | |

| Cardioselective calcium antagonists (verapamil and diltiazem) | Increased ciclosporin levels | |

| Amiodarone | Increased ciclosporin levels | |

| Ciprofloxacin | Acenocoumarol | Increased INR |

| Metronidazole | Statins | Increased risk of neuropathy |

| Acenocoumarol | Increased INR | |

| Filgotinib | Fenofibrate, carvedilol, diltiazem, simvastatin | Filgotinib is mainly metabolised by carboxylesterase-2 (CES2), which can be inhibited in vitro by drugs such as fenofibrate, carvedilol, diltiazem and simvastatin. The clinical relevance of this interaction is unknown |

| Upadacitinib | Rosuvastatin, atorvastatin | Decreased levels/exposure to rosuvastatin and atorvastatin |

| Ozanimod | Gemfibrozil, clopidogrel | Increased levels of ozanimod |