Chronic immune-mediated diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), present an increased risk of developing early atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events (CVE) at early age.

ObjectiveTo describe the baseline and 1-year cardiovascular profile of patients with IBD according to the biologic treatment received, taking into account the inflammatory activity.

Patients and methodsIt is a retrospective, observational study that included 374 patients. Cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF) and CVE were collected at the baseline visit and at one-year follow-up to describe the cardiovascular risk according to the biological treatment received, also assessing clinical and biological remission.

ResultsA total of 374 patients were included: 146 (38.73%) were treated with Infliximab, 128 (33.95%) with adalimumab, 61 (16.18%) with ustekinumab and 42 (11.14%) with vedolizumab.

The changes in blood glucose levels are [86.31 mg/dl (84.57–88.06) vs. 89.25 mg/dl (87.54–90.96), p = 0.001] for those treated with antiTNFα and [86.52 mg/dl (83.48–89.55) vs. 89.44 mg/dl (85.77–93.11), p = 0.11] in the other group.

In the group treated with antiTNFα total cholesterol values at baseline visit are [169.40 mg/dl (164.97–173.83) vs. 177.40 mg/dl (172.75–182.05) at one year of treatment, p = <0.001], thoseof HDL [50.22 mg/dl (48.39–52.04) vs. 54.26 mg/dl (52.46–56.07), p = <0.001] and those of tri-glycerides [114.77 mg/dl (106.36–123.18) vs. 121.83 mg/dl (112.11–131.54), p = 0.054].

Regarding weight, an increase was observed, both in those patients treated with antiTNFα [71.39 kg (69.53–73.25) vs. 72.87 kg (71.05–74.70) p < 0.001], and in the group treated with ustekinumab and vedolizumab [67.59 kg (64.10–71.08) vs. 69.43 kg (65.65–73.04), p = 0.003].

Concerning CVE, no significant differences were observed neither according to the drug used (p = 0.36), nor according to personal history of CVE (p = 0.23) nor according to inflammatory activity (p = 0.46).

ConclusionsOur results on a real cohort of patients with IBD treated with biologic drugs show a better control of certain cardiovascular parameters such as CRP or HDL, but a worsening of others such as total cholesterol or triglycerides, regardless of the treatment. Therefore, it is possibly the disease control and not the therapeutic target used, the one that affect the cardiovascular risk of these patients.

Las enfermedades crónicas inmunomediadas, entre las cuales se encuentra la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII), presentan un riesgo mayor de desarrollar aterosclerosis precoz y eventos cardiovasculares (ECV) a edades tempranas.

ObjetivoDescribir el perfil cardiovascular basal y al año de tratamiento de los pacientes con EII según el tratamiento biológico recibido, teniendo en cuenta la actividad inflamatoria.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio retrospectivo y observacional que incluyó 374 pacientes. Se recogieron los factores de riesgo cardiovascular(FRCV) y los ECV en la visita basal y al año de seguimiento para describir el RCV según el tratamiento biológico recibido, valorando también la remisión clínica y biológica.

ResultadosSe incluyeron un total de 374 pacientes 146 (38,73%) fueron tratados con infliximab, 128 (33,95%) con adalimumab, 61 (16,18%) con ustekinumab y 42 (11,14%) con vedolizumab.

Los cambios en el valor de glucemia son 86,31 mg/dl (84,57–88,06) vs. 89,25 mg/dl (87,54–90,96), p = 0,001, en el caso de los tratados con antifactor de necrosis (TNF)-α y de 86,52 mg/dl (83,48–89,55) vs. 89,44 mg/dl (85,77–93,11), p = 0.11, en el otro grupo.

En el grupo tratado con antiTNFα los valores de colesterol total en la visita basal son 169,40 mg/dl (164,97–173,83) vs. 177,40 mg/dl (172,75–182,05) al año de tratamiento, p = <0,001, los de HDL 50,22 mg/dl (48,39–52,04) vs. 54,26 mg/dl (52,46–56,07), p = <0.001, y los de triglicéridos 114,77 mg/dl (106,36–123,18) vs. 121,83 mg/dl (112,11–131,54), p = 0,054.

En cuanto al peso, se observó un aumento, tanto en aquellos pacientes tratados con anti-TNF-α (71,39 kg [69,53–73,25] vs. 72,87 kg [71,05–74,70], p < 0,001), como en el grupo tratado con ustekinumab y vedolizumab (67,59 kg [64,10–71,08] vs. 69,43 kg [65,65–73,04], p = 0,003].

En cuanto a los ECV, no se observaron diferencias clínica ni estadísticamente significativas ni en función del fármaco utilizado (p = 0,36), ni atendiendo a los antecedentes personales de ECV (p = 0,23) ni según la actividad inflamatoria (p = 0,46).

ConclusionesNuestros resultados sobre una cohorte real de pacientes con EII en tratamiento con fármacos biológicos objetivan un mejor control de ciertos parámetros cardiovasculares tales como la PCR o el HDL, pero con empeoramiento de otros como el colesterol total o los triglicéridos, independientemente del fármaco utilizado. Por lo tanto, es posiblemente el control de la enfermedad y no la diana terapéutica empleada lo que influya sobre el riesgo cardiovascular de estos pacientes.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) includes a series of chronic disorders, in which the physiological situation of immunological tolerance between luminal antigens and the host is broken, developing an excessive immune response that produces lesions of variable depth and extension in the intestine. Its main clinical manifestations are ulcerative colitis (UC), Crohn's disease (CD) and indeterminate colitis (IC).1,2

IBD is one of the so-called chronic immune-mediated diseases (CIMDs), which also include rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus and systemic sclerosis. Several studies3–5 have shown the association between this group of diseases and cardiovascular disease. Those with CIMDs have a higher risk of developing early atherosclerosis and coronary microvascular dysfunction and, therefore, a higher risk of suffering cardiovascular events (CVEs) at an early age. A direct relationship would then be established between the degree of inflammation present in affected individuals and the risk of developing CVEs.6,7

Anti-tumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF)-α drugs have been shown to be effective in reducing cardiovascular risk (CVR) in these CIMDs.8–10 However, due to their mechanism of action, we cannot determine whether this efficacy is due to adequate control of inflammation or to the blockade of cytokine that is involved in both the atherogenic and proinflammatory processes.11

Taking the above into account, in our study we aimed to describe the changes in CVR factors in patients with IBD at the beginning and one year of treatment, according to whether they received anti-TNF-α or other molecules with therapeutic targets (ustekinumab/vedolizumab). As a secondary objective, we assessed the presence of CVEs taking into account the treatment and the inflammatory activity of the disease.

Patients and methodsThis study is a retrospective and observational study. Patients diagnosed with CD, UC, and indeterminate colitis (IC) between January 2006 and January 2020 were included, according to the criteria of the European guidelines.1,2 We only included those patients for whom the indication for starting treatment was intestinal luminal activity and who had continued stable follow-up in our centre from the start of biologic therapy to the present.

CVR factors, including body mass index (BMI), arterial hypertension (AHT), glycaemia, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol (HDL-C), triglycerides and prealbumin were collected during the baseline visit prior to the start of biologic therapy and at one year of treatment.

Major CVEs (stroke, myocardial infarction) were also collected from the start of biologic therapy until the end of follow-up.

Likewise, the variables related to the patient's IBD were obtained, such as type, perianal involvement, presence of extraintestinal manifestations, family history, smoking habit and indication for the start of treatment. On the other hand, by reviewing the clinical history, variables related to the inflammatory state of the disease were collected during the baseline visit and after one year of treatment. The presence of clinical remission was defined by partial Mayo score ≤1 for UC and Harvey-Bradshaw index ≤4 for CD. To establish biochemical remission, C-reactive protein (CRP) values <5 mg/dl were set.

A descriptive analysis of the patients' baseline characteristics and of those related to their IBD was performed. For continuous variables, the mean and standard deviation were calculated; for the categorical variables, the percentages and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. Provided that the variables had a normal distribution (verified using the Shapiro-Wilk test), the categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test, and the quantitative variables using the Student's t-test for related samples. Otherwise, the Wilcoxon non-parametric test was applied. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. For data analysis, the Stata version 15 program (StataCorp, 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC) was used.

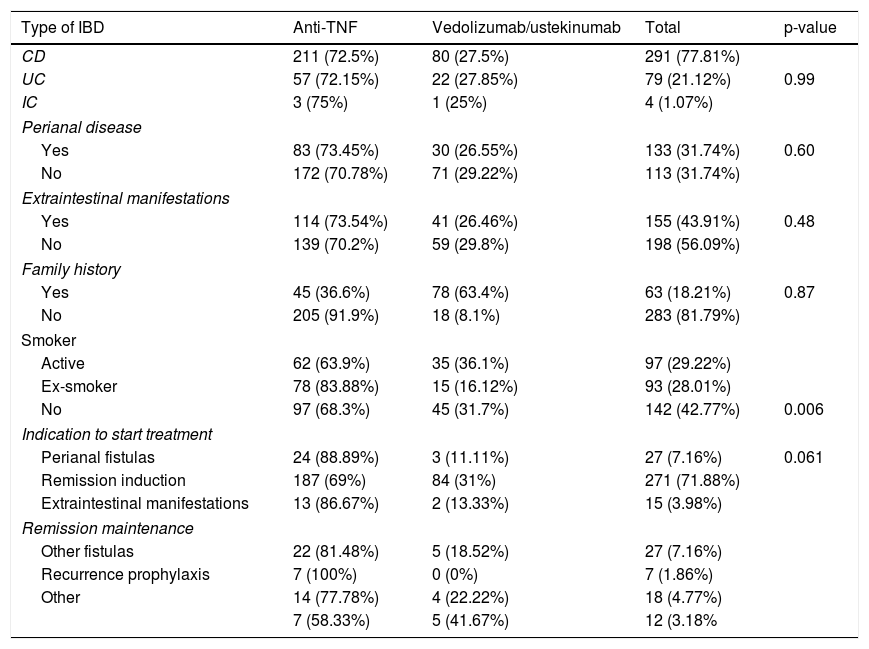

ResultsA total of 374 patients were included. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the included patients. Of our patients, 291 (77.81%) had CD, 79 (21.12%) had UC, and four (1.07%) had IC. Of these, 146 (38.73%) were treated with infliximab, 128 (33.95%) with adalimumab, 61 (16.18%) with ustekinumab, and 42 (11.14%) with vedolizumab.

Baseline characteristics of the included patients.

| Type of IBD | Anti-TNF | Vedolizumab/ustekinumab | Total | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD | 211 (72.5%) | 80 (27.5%) | 291 (77.81%) | |

| UC | 57 (72.15%) | 22 (27.85%) | 79 (21.12%) | 0.99 |

| IC | 3 (75%) | 1 (25%) | 4 (1.07%) | |

| Perianal disease | ||||

| Yes | 83 (73.45%) | 30 (26.55%) | 133 (31.74%) | 0.60 |

| No | 172 (70.78%) | 71 (29.22%) | 113 (31.74%) | |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | ||||

| Yes | 114 (73.54%) | 41 (26.46%) | 155 (43.91%) | 0.48 |

| No | 139 (70.2%) | 59 (29.8%) | 198 (56.09%) | |

| Family history | ||||

| Yes | 45 (36.6%) | 78 (63.4%) | 63 (18.21%) | 0.87 |

| No | 205 (91.9%) | 18 (8.1%) | 283 (81.79%) | |

| Smoker | ||||

| Active | 62 (63.9%) | 35 (36.1%) | 97 (29.22%) | |

| Ex-smoker | 78 (83.88%) | 15 (16.12%) | 93 (28.01%) | |

| No | 97 (68.3%) | 45 (31.7%) | 142 (42.77%) | 0.006 |

| Indication to start treatment | ||||

| Perianal fistulas | 24 (88.89%) | 3 (11.11%) | 27 (7.16%) | 0.061 |

| Remission induction | 187 (69%) | 84 (31%) | 271 (71.88%) | |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | 13 (86.67%) | 2 (13.33%) | 15 (3.98%) | |

| Remission maintenance | ||||

| Other fistulas | 22 (81.48%) | 5 (18.52%) | 27 (7.16%) | |

| Recurrence prophylaxis | 7 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (1.86%) | |

| Other | 14 (77.78%) | 4 (22.22%) | 18 (4.77%) | |

| 7 (58.33%) | 5 (41.67%) | 12 (3.18% | ||

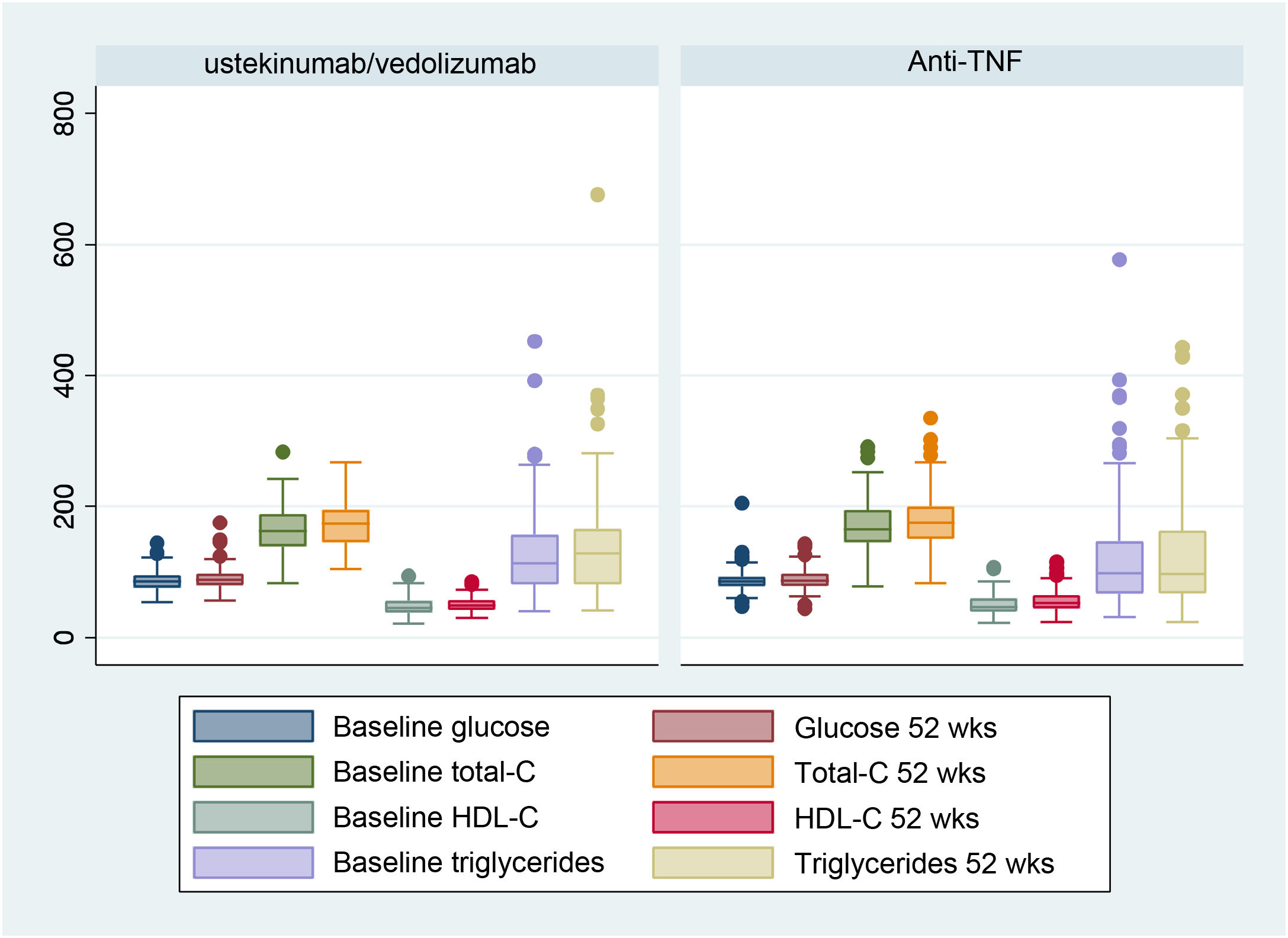

Fig. 1 shows the analytical values of the different CVR factors in both treatment groups (anti-TNF-α vs. vedolizumab and ustekinumab), comparing the initial visit and the one-year follow-up.

The changes in the glycaemia value were 86.31 mg/dl (84.57–88.06) vs. 89.25 mg/dl (87.54–90.96), p = 0.001, in the case of those treated with anti-TNF-α and 86.52 mg/dl (83.48–89.55) vs. 89.44 mg/dl (85.77–93.11), p = 0.11, in the other group.

In the group treated with anti-TNF-α, total cholesterol (total-C) values at the baseline visit were 169.40 mg/dl (164.97–173.83) vs. 177.40 mg/dl (172.75–182.05) after one year of treatment, p < 0.001, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) values were 50.22 mg/dl (48.39–52.04) vs. 54.26 mg/dl (52.46–56.07), p < 0.001, and triglyceride values were 114.77 mg/dl (106.36–123.18) vs. 121.83 mg/dl (112.11–131.54), p = 0.054.

In those treated with vedolizumab and ustekinumab, the total-C values were 159.77 mg/dl (152.27–167.26) vs. 172.33 mg/dl (165.27–179.39), p < 0.001, HDL-C values were 47.38 mg/dl (44.15–50.60) vs. 50.44 mg/dl (47.56–53.31), p = 0.018, and triglyceride values were 128.83 mg/dl (113.23–144.43) vs. 142.08 mg/dl (122.03–162.13), p = 0.042.

Regarding the CRP values, we found a decrease in these after one year of treatment. The values in the anti-TNF-α group were 10−45 mg/l (7.75–13.14) vs. 3.55 mg/l (2.36–4.73), p < 0.001, and 17.76 mg/l (11.45–24.07) vs. 4.41 mg/l (3.37–5.45), p < 0.001, in those treated with vedolizumab and ustekinumab.

Regarding prealbumin values in those treated with anti-TNF-α, they were 27.16 mg/dl (19.87–34.45) vs. 30.37 mg/dl (24.84–35.90), p = 0.14. In the group treated with vedolizumab and ustekinumab, the values were 23.21 mg/dl (12.92–33.50) vs. 27.31 mg/dl (18.84–35.78), p = 0.55.

Regarding weight, an increase was observed, both in those patients treated with anti-TNF-α (71.39 kg [69.53–73.25] vs. 72.87 kg [71.05–74.70], p < 0.001), as in the group treated with ustekinumab and vedolizumab (67.59 kg [64.10–71.08] vs. 69.43 kg [65.65–73.04], p = 0.003).

Within our sample, of the 101 patients who did not present diabetes at baseline, two (1.98%) developed the disease after treatment (p < 0.001). In the case of AHT, three patients (1.11%) of the 271 healthy patients at baseline developed it (p < 0.001).

Regarding CVEs, no clinically or statistically significant differences were observed, neither depending on the drug used (p = 0.36), nor according to the CVE personal history (p = 23) or inflammatory activity (p = 0.46). Nine patients (.39%) presented a new CVE, of which four (1.06%) were treated with infliximab, two (0.53%) with adalimumab, three (0.79%) with ustekinumab, and none with vedolizumab.

DiscussionIn IBD, there are studies that show lower total and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol values at diagnosis than in the healthy population,12 without this implying a protective factor against the development of CVEs, since these lower values are explained in the context of consumption by chronic inflammation.

As we observed in our sample, adequate treatment of the disease leads to an increase in cholesterol values, equating them to those of the general population. Therefore, it might be necessary to monitor lipid levels post-treatment to determine if the increase after control of the disease is associated with CVEs.

Regarding weight, although patients with IBD classically have a lower BMI, obesity is currently an emerging threat.13,14 The patients included in our study are a clear example of this change, since the mean BMI values, both at the baseline visit (BMI 24.49, SD 4.58) and at one year of treatment (BMI 24.93, SD 4.74), are in the overweight range.

There are retrospective studies that show how an increase in the BMI of patients treated with infliximab would translate into a greater probability of presenting a disease flare despite good therapeutic compliance.15 Accordingly, the data on weight gain obtained after one year of treatment should be treated with caution, since we cannot distinguish between the gain due to better control of the underlying disease and the gain secondary to poor hygienic-dietary habits.

In our sample, we also observed an increase in blood glucose levels in both groups. Focusing on their clinical significance, reflected in the development of diabetes mellitus, 1.98% of the patients developed the disease after treatment, demonstrating a statistically significant association (p < 0.001), despite the small sample size.

Although to date the possible relationship between IBD and diabetes has not clearly been established, several studies suggest an increased risk of developing diabetes in patients with a state of chronic inflammation.16 In this sense, a study carried out on the South Korean national cohort shows a higher incidence of diabetes in patients with IBD, after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, smoking habit and physical exercise. Especially in those with CD and under 40 years of age.17

The rate of development of AHT in our study after one year of treatment is 1.11% and shows a statistically significant increase (p < 0.001). These data would go against what was collected in previous studies, where a lower rate of hypertension was observed in patients with IBD.18 This trend that we observed would require a more exhaustive study, in order to discern the cause of this increase in our patients.

Regarding serum markers, the CRP values of our patients show a clearly significant reduction one year after the start of treatment, which would correspond to better control of inflammation and a decrease in CVR.

Regarding biologic drugs, more recent IBD studies show a reduction in the risk of CVEs in those patients treated with anti-TNF-α drugs, especially in men with CD.19

In our study, although the number of CVEs was very limited, we found data consistent with previous findings, since a greater number of events was not observed, regardless of the drug used.

More recently, a study has been conducted in patients with IBD treated with ustekinumab with results that contradict previous evidence. This study, published in 2020 in a French cohort, shows a higher risk of having CVEs in the first six months after starting treatment among those patients with high CVR (OR 4.17; 95% CI, 1.19–14.59).20 These data would be supported by the hypothesis of an acute immunological change induced after the start of biologic therapy, which would act on the atheromatous plaque, destabilising it.

In our sample, the number of CVEs in patients treated with the different types of biologics was low (2.39%). We did not observe an influence of the type of biologic or the control of inflammatory activity, so our results would support previous findings,21,22 which indicate that there are no substantial differences in the cardiovascular risk associated with the use of different biologic drugs, although our results may not be conclusive because the low number of CVEs recorded is insufficient to detect significant differences, if any.

On the other hand, in our sample, patients with CVR factors and a history of CVEs showed a similar CVE risk after one year of treatment, regardless of the drug used, and not different from the general population,23 understood as those patients with no history of interest. This fact could be useful in clinical practice when choosing which treatment to start in a patient with a personal history of CVEs, since these would not limit the choice according to our data, although prospective studies would be necessary to confirm our results where the number of CVEs in the sample had sufficient statistical power.

ConclusionsWe describe the evolution of the cardiovascular profile of a real cohort of patients with IBD under treatment with biologic drugs. We observed better control of certain cardiovascular parameters, such as CRP or HDL-C, but worsening of others such as total cholesterol, triglycerides or blood glucose, regardless of the drug used. Therefore, it is possibly the control of the disease and not the therapeutic target used that influences cardiovascular risk.

In addition, the results suggest that these treatments do not lead to an increase in CVEs for patients, although, given the low number of CVEs in our sample, prospective, population-based studies are necessary to reach these conclusions.

Ethical considerationsIn compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the data of the patients included in the analysis were anonymised. Since this study was a retrospective analysis of deidentified data, an Ethics Committee review was not required or requested.

FundingNo funding of any kind has been received for conducting this study.

Conflicts of interestCristina Suárez Ferrer has received funding for training and has collaborated with Abbvie, Takeda, Jannsen, MSD, Thillotts Pharma, Pfizer. María Dolores Martín Arranz has received honoraria as a speaker, consultant and advisory member, and has received research funding from MSD, AbbVie, Hospira, Pfizer, Takeda, Janssen, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Tillotts Pharma, Faes Pharma. These companies make medical treatments for IBD. Eduardo Martín Arranz has received financial support for travel and educational activities, and has received fees as a speaker or consultant from Janssen Ferring, MSD, AbbVie and Takeda. Joaquín Poza Cordón has received funding for training and has collaborated with Janssen, AbbVie, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Shire Pharmaceuticals. María Sánchez Azofra has received financial support for trips and educational activities, and has received speaker fees from Janssen, Takeda, Pfizer, Tillotts Pharma, Ferring Pharmaceuticals. Jose Luis Rueda García has received financial support for travel and educational activities, and has received speaker fees from Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda, Ferring, Tillotts Pharma, Faes Farma, Norgine, and Casen Recordati.