This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention that involved interactions within a simulated health care space to reduce medical fear among children in infant classes.

MethodsAn experimental study involving 86 children divided into an intervention group and a control group with pre- and postintervention measurements was undertaken. The intervention, known as the Health-Friendly Program, consisted of showing children various scenarios that simulated different medical contexts so that they could interact in them, experiment with the materials and ask questions. Medical fear was evaluated using the Spanish version of the revised “Child Medical Fear Scale”, which provides a score of the medical fear level ranging between 0 and 34 points. The pretest and posttest levels of medical fear in the intervention and control groups were compared with Student's t test.

ResultsThe children in the intervention group experienced a significant reduction in fear by 3.21 points (SD: 6.50) compared to the children in the control group. This reduction in fear was shown in all four dimensions of the scale: intrapersonal fears, procedural fears, environmental fears and interpersonal fears.

ConclusionThe Health-Friendly Program provides an innovative intervention to reduce medical fear among children based on information, confrontation strategies and simulation scenarios. This study suggests the potential benefit of incorporating educational interventions in schools in collaboration with university and health care simulation centers.

El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar la efectividad de una intervención que implicó interacciones dentro de un espacio de atención sanitaria simulado para reducir miedo al entorno médico entre los niños de educación infantil.

MétodosSe llevó a cabo un estudio experimental que implicó a 86 niños, divididos en los grupos intervención y control, con medidas antes y después de la intervención. Dicha intervención, denominada Programa Health-Friendly, consistió en enseñar a los niños diversos escenarios que simularon diferentes contextos médicos, para que pudieran interactuar en ellos, experimentar con los materiales y realizar preguntas. El miedo al entorno médico fue evaluado mediante la versión en español revisada de “Child Medical Fear Scale”, que proporciona una puntuación al nivel de miedo al entorno médico que fluctúa de 0 a 34 puntos. Los niveles de miedo al entorno médico antes y después de la prueba en los grupos intervención y control fue comparado mediante la prueba de Student.

ResultadosLos niños del grupo intervención experimentaron una reducción significativa del miedo de 3,21 puntos (DE: 6,50) en comparación con los niños del grupo control. Dicha reducción del miedo se reflejó en las cuatro dimensiones de la escala: miedos intrapersonales, miedos procedimentales, miedos ambientales y miedos interpersonales.

ConclusiónEl Programa Health-Friendly proporciona una intervención innovadora para reducir el miedo al entorno médico entre los niños, basada en información, estrategias de confrontación y escenarios de simulación. Este estudio sugiere el beneficio potencial de incorporar intervenciones educativas en las escuelas, en colaboración con los centros universitarios y los centros de simulación de la atención sanitaria.

Children are especially vulnerable to medical fear. Several strategies have been implemented to reduce children’s fear and anxiety, mainly oriented to the hospital context.

What it contributeThis article contributes to illustrate the effectiveness of an innovative preventive intervention based on information, confrontation strategies and simulation scenarios to reduce medical fear among children, both in the context of inpatient and outpatient care.

Children generally show fear of contact within health care environments. This manifests as worrying about the medical appointment, during hospital admission or when certain procedures are going to be performed. These medical experiences often imply the separation of children from their family, friends and familiar environments.1 This is compounded by an invasion of the child’s privacy through actual threats to their body from the tests and procedures that they might have to undergo or due to being in hospital.1 These experiences are perceived by children as threatening and, depending on the child, can produce some level of fear or dread.1 Furthermore, dread can increase as a consequence of a child being in an unknown environment with equipment and people who are strange to them.2

Fear is an unpleasant emotion that is regulated as children mature. It has been defined as a specific biological and psychological response to a real or imaginary threat.3 Medical fear is the fear of any situation that implies contact with health care professionals or procedures being carried out during medical care.4 This fear can differ by age group. Children under 7 years old might experience more diffuse fear and feelings of discomfort.5 Furthermore, their limited understanding of certain medical procedures and the fantasies that probably stem from this can also exacerbate their fear.5

Experiencing medical fear can have negative consequences for children, significantly impacting patient outcomes. Evidence suggest that this phenomenon is related to immunization non-compliance, higher pain levels, a greater likelihood of delay in recovery or infection.6–9

Aiming to make pediatric healthcare spaces more child-friendly and less threatening,10 an attempt has been made to attractively decorate spaces with children’s themes, background music, and toys; health care professionals have even begun to wear colored uniforms when they care for younger patients.6,11 Experiences have also been described, such as the “Teddy Bear Hospital” program, where young children are immersed in a hospital for teddy bears and become health professionals for a day, going from room to room and carrying out different procedures with their teddy bear patients.12 The main objective is that children lose their fear of any real contact that they might subsequently have within a health care environment.12,13 Another example is the website www.doctortea.org, which was designed to help people with autism spectrum disorder and other disabilities and their families prepare for visits to the doctor. This website offers information in different formats (videos, animations, pictograms or cartoons) on the medical procedures and interventions conducted most frequently among the youngest patients. This website receives over 15,000 visits a year, with users from 70 different countries.14

Despite these initiatives, little is known about how children handle and experience pain and fear during hospital care or primary health care center visits.15 In Kleye’s study.15 researchers identified which strategies children aged 4–12 years used to control fear and pain during medical procedures that involved needles. They described strategies such as trying to be brave and controlling their thoughts (which would depend on the child’s age), lying down, holding someone’s hand or the possibility of shouting as a release to reduce the fear and pain. Children were helped to cope by having a toy or a soft toy, playing with other children, looking at decorations in the environment and using technology, and their fear and pain was lessened. In addition, they described the support that they could obtain from adults and their environment, the importance of being informed immediately before the procedure or treatment and the importance of feeling involved in decision-making.15

As an strategy to reduce medical fear among children, a complementary intervention was proposed in addition to the education that children receive at school in relation to health, illness and healthy habits, as these areas of knowledge are included in the educational planning of preschools in different countries.16–18 This is thereby the point at which children become aware of health care professionals, the human body and the health care context.

The complementary intervention is based on giving children the opportunity to not only work on these aspects more theoretically in the classroom but also to learn and experiment in a physical space that accurately simulates the real world: scenarios include having nurse consultation at a primary health care center, being in a hospital room, etc. It is precisely this contact with recreated spaces that can generate feelings of trust and knowledge among children, which reduces their fear during real exposure to health care environments. Similar experiences include hospital visits to see the units or spaces where a child is going to spend time during their hospital stay or surgery.19–21 These are interventions based on information where children can become familiar with the places and even with the equipment and devices that will be used. Although evidence that these interventions reduce presurgery anxiety among children has been shown,10,20 no research has explored health care simulation-based programs to address medical fear.22

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention that involved interactions with a simulated health care space to reduce medical fear among children in infant classes.

The hypothesis of the study was as follows:

Hypothesis 1The Health-Friendly Program will significantly reduce medical fear among children. Furthermore, the reduction in medical fear in the intervention group will be greater than that in the control group.

MethodsDesignA cluster randomized controlled trial was conducted involving an intervention group (IG) and a control group (CG) with pre- and postintervention measurements. The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (unique identifier: NCT06012877).

Population and study settingThe context of the study included two schools from a town in northern Spain. These schools were randomly selected using the lottery method from a list of schools that had a collaboration agreement with the university where the study was performed. One of the schools was a charter school and the other a public school, offering diversity in the study sample. The university where the intervention took place was the Public University of Navarre (UPNA), which is the only public university of the region.

In total, 128 boys and girls in the third year of preschool (6 years old) at two schools (School A and B) were enrolled in the study. The children included in the sample had similar characteristics regarding their history of illness (i.e., common childhood illnesses without serious pathologies) and previous contact with health care environments.

The sample size was estimated by considering a type I error of 0.05, a type II error of 0.2 (80% power) and a minimum effect of 2.5 points for the pre-post intervention difference between the intervention and the control group. Assumptions related with the variability were that SD of the ‘fear’ scale was 5 points,1 and the within individual pre-post correlation was r = 0.85. The sample size was 42 subjects in each group.

The children were divided into the IG and CG by randomizing the classes (clusters) taking part in the intervention and those forming the CG. It was decided to perform the intervention in the class groups to avoid the risk of contamination.23 Consequently, classes were gradually added to the study according to the order established by randomization (using a computer-generated random list of random numbers) until a sample of 43 children was obtained in each group. A total of 3 classes were included in the IG (2 classes from School A) and 4 classes were included in the CG (2 classes from School A and 2 classes from School B) due to differences between class sizes and differences in willingness to participate in the study. The allocation sequence was concealed from the members of the research team who collected the data.

InterventionThe intervention, known as the Health-Friendly Program, took place at the Clinical Skills and Simulation Centre of the Faculty of Health Sciences of the Public University of Navarre (UPNA) in October 2019. The intervention consisted of showing the children different scenarios that simulated various medical contexts, letting them experiment with the materials and ask questions.

The structure and content of the intervention were intended to address two main issues. The first issue was the health contexts with which school-age children may come into contact; these included a consultation at a health center and being in a hospital room. The second issue was concerns related to intrapersonal, procedural, environmental and interpersonal aspects experienced by children when they interact with health care professionals or are sick.24

The intervention is described in detail in the guide about the Health-Friendly Program.25 The guide explains the aim, the evaluation measures and the development of each scenario, with details about the physical space, the materials and the instructor script for each scenario.

As part of the intervention, we recreated 3 different scenarios, as follows:

- -

A nurse consultation at a health center: two instructors simulating the role of a nurse explained the need for periodic health check-ups and a healthy lifestyle, the importance of vaccines, and hygiene measures while also inviting children to weigh and measure themselves. Children were shown and able to manipulate the following materials: syringes, vials, cotton, antiseptics, phonendoscopes, otoscopes, reflex hammers, blood pressure monitors, depressors, flashlights and thermometers.

- -

A hospital unit: an instructor played the role of the nurse, and another instructor simulated a real patient. They talked to the children about staying in the hospital and different medical procedures and explained that in these cases, children are accompanied by their parents Children had the opportunity to use a pulse oximeter to measure their oxygen saturation. Children were shown and able to manipulate the following materials: analytical tubes, racks,compressors, and anatomical models of abdominal organs or a skeleton.

- -

A discovery Room: this room, run by two instructors, set up a dialog and played children’s videos, addressing various ideas on illness and being sick. Children also practiced dressing wounds on a full-body mannequin with simulated injuries. The following wound care materials were prepared: saline solution, antiseptic, gauze and dressings, as well as hydroalcoholic gel for hand hygiene.

The children entered the spaces in groups of 8–10 and stayed for 15−20 min.

Children in the IG came to the center during a school trip and were accompanied by their teachers. Each class attended on a different day.

Members of the research team who were not involved in the data collection and six students, including fourth-year nursing degree students and students from a health sciences research master’s degree program, took part as instructors to run the intervention. Several strategies were implemented to ensure the homogeneous development of the intervention among the different groups. The instructors were previously trained on the study protocol, and understood their role in the specific scenario and the script to be followed. The script for each scenario detailed the activities to be carried out, the information to be provided and the questions to be asked. There were two instructors in each scenario and another member of the research team monitoring the time. This person rotated through the different scenarios to confirm the instructors’ adherence to the protocols and scripts.

ControlChildren in the CG continued with normal activities at school and at home, similar to the children in the IG, so the only difference between the two groups was taking part in the intervention. Once the poststudy data had been collected from all participants, children in the CG also took part in the intervention a few days later.

VariablesInformation was collected on sex as the main sociodemographic variable.

The variable of interest, fear, was measured using the revised “Child Medical Fear Scale” (CMFS-R),24 in its validated Spanish version that has demonstrated acceptable levels of validity and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87).26 The scale has 17 items with statements on fear of certain aspects related to health care environments, which children answer according to a three-point scale (0 = no fear, 1 = some fear and 2 = very frightened). The maximum total scale score is 34 points. The validation of the Spanish version confirmed the existence of the 4 dimensions identified in the original CMFS-R: intrapersonal, procedural, environmental and interpersonal fears.26

As children aged under 6 years old were involved, a member of the research team read the items aloud to them so they could answer. Considering Piaget’s theory,27 which states that children of preoperational age (3–7 years old) are not capable of quantifying abstract phenomena, the answer format was changed to a visual face scale that represented facial expressions for “no fear”, “some fear” and “very frightened”.28 This approach has been used in other studies using this scale.24

Data collectionThe data were collected using the online questionnaire platform SurveyMonkey©. An electronic questionnaire that included the 17 items from the Spanish version of the CMFS-R and a question to determine sex was generated and completed by researchers. To do this, two members of the research team went to the schools, and the children were brought out of the classroom one by one to answer the questionnaire. The preintervention data were collected one day before the intervention, for participants in both the IG and CG, and the postintervention data were collected one week after the intervention, also from all participants. As explained, these researchers were not aware of the participants’ group allocation. Data collection was completed over a two-month period. In the first month, data were collected from the classes of School A, and in the second month, data were collected from the classes of School B.

Data analysisDescriptive statistics were initially used, such as central trend (mean) and dispersion (standard deviation, SD) measurements for quantitative variables and percentages and frequencies for qualitative variables. Normality tests were performed to verify the assumption that the data followed a normal distribution. For this purpose, the Shapiro-Wilks test was used, taking into account the sample size with 43 participants in each group (control group and intervention group). This test tends to be robust even with relatively small sample sizes and is effective in detecting deviations from normality. The results showed a p value greater than 0.05, thus suggesting that the data conformed to a normal distribution.

Subsequently, the equivalence in the distribution of boys and girls in both groups was determined using the chi-square test. To evaluate the effect of the intervention within each group, Student's t-test for paired samples was used. Again, Student's t-test for independent samples allowed us to compare the results between the IG and the CG after the intervention and to determine whether there were significant differences between the groups after the intervention. In addition, a multiple linear regression analysis examined the relationship between the independent variables (group membership (CG/GI), sex and the pre-intervention measure) and the dependent outcome variable (post-intervention measure; CMFS-R score). The “intro” method was used to introduce the variables to the model. The level of significance was 0.05, and the SPSS 25.0 computer program was used to analyze the data.

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the Committee of Ethics and Animal Experimentation at the Public University of Navarre (approval number: PI-030/19). The parents or legal guardians of each child were informed about the study, what the child’s participation would involve, the confidentiality of data and that they could leave the study at any point without affecting their child in any way. The class teachers sent the information sheet and consent form to the parents, who were asked to return the signed consent form if they would allow their child to participate in the study.

Data collection was anonymous. Data confidentiality was ensured by creating an identification code for each participant that made it possible to link the questionnaires at both points of the study (pre and post). No other personal information was collected.

Permission was obtained from the school principals of both centers. Two members of the research team held a meeting with the management team and teachers of the Preschool Education Cycle to present the Health-Friendly Program and the study. After the completion of data collection, children allocated to the control group also participated in the Health-Friendly Program within a few days.

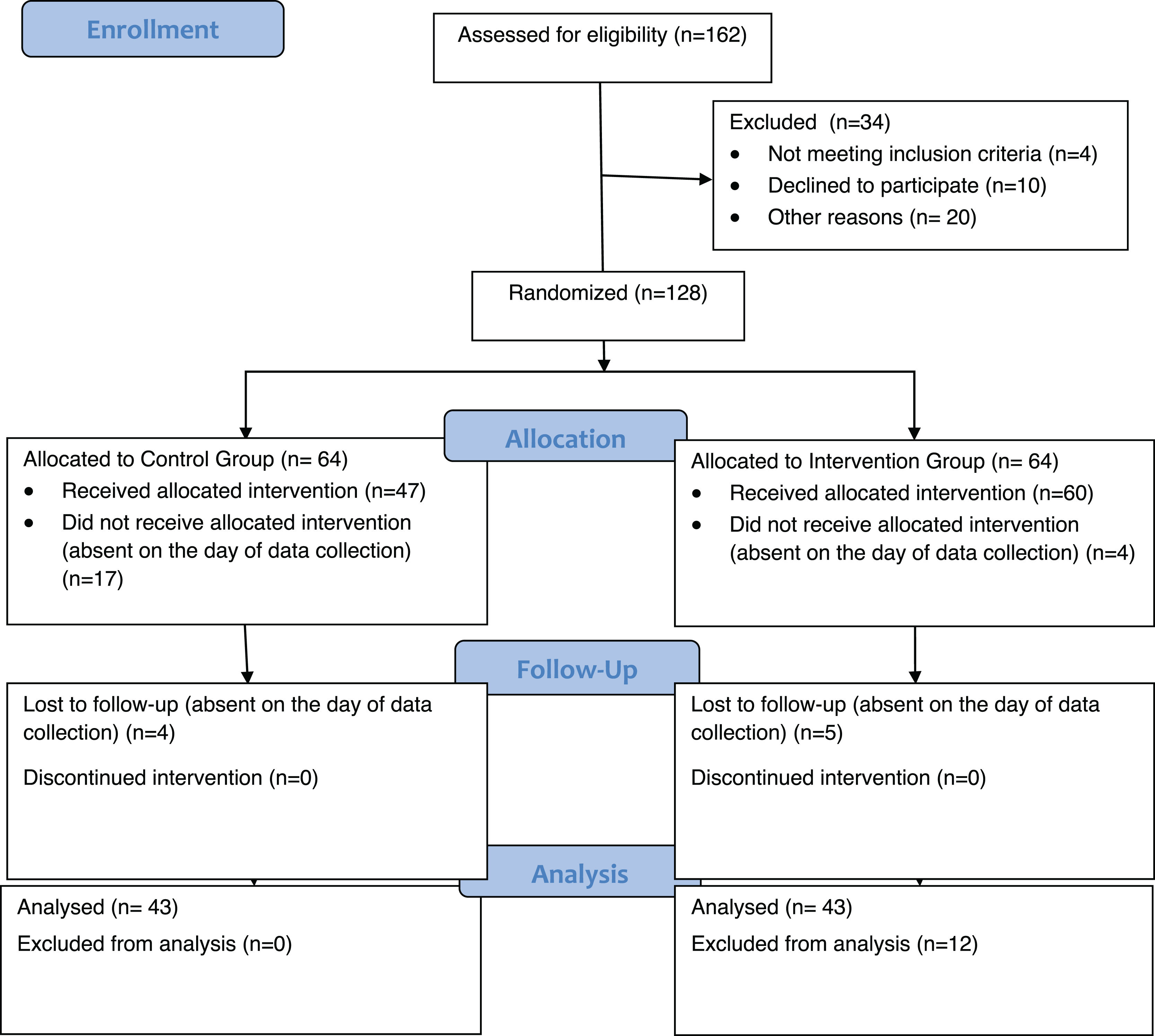

ResultsUltimately, 86 children took part in the study, with 43 children in each group. The flow of participants through each phase is presented in Fig. 1.

Out of the 43 participants in the CG, 58.1% (n = 25) were girls, while the percentage of girls in the IG was 44.2% (n = 19). The chi-square statistics show that the groups were homogeneous in terms of the proportion of girls and boys in each group (p = 0.196).

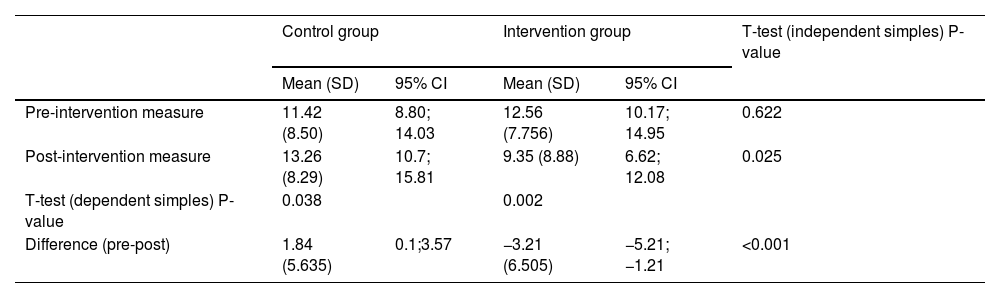

Table 1 presents the data related to the main variable “medical fear” and the results of the statistical significance of this difference. There were no significant differences in the mean baseline score between the two groups. Changes between pre- and postintervention measurements revealed a statistically significant difference between the CG and IG: while participants in the IG showed reduced levels of medical fear (CI 95%: −5.21; −1.21), those in the CG showed increased levels (CI 95%: 0.1; 3.57).

Pre-post measures of the variable medical fear and differences between control and intervention group.

| Control group | Intervention group | T-test (independent simples) P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | 95% CI | Mean (SD) | 95% CI | ||

| Pre-intervention measure | 11.42 (8.50) | 8.80; 14.03 | 12.56 (7.756) | 10.17; 14.95 | 0.622 |

| Post-intervention measure | 13.26 (8.29) | 10.7; 15.81 | 9.35 (8.88) | 6.62; 12.08 | 0.025 |

| T-test (dependent simples) P-value | 0.038 | 0.002 | |||

| Difference (pre-post) | 1.84 (5.635) | 0.1;3.57 | −3.21 (6.505) | −5.21; −1.21 | <0.001 |

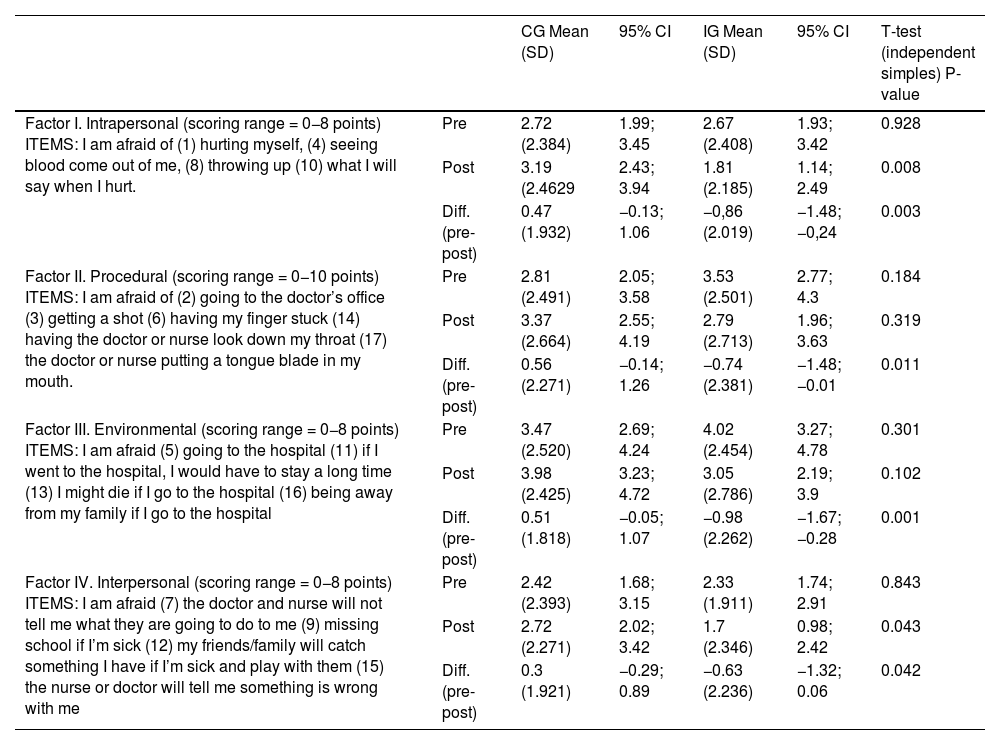

The analysis of the difference between pre- and postintervention scores in each of the 4 dimensions of the scale (i.e., procedural fears, environmental fears, intrapersonal fears and interpersonal fears) demonstrated a significant reduction in medical fear in the IG for the intrapersonal, procedural and environmental dimensions, while the level of fear remained stable for the interpersonal dimension. In the CG, no variation was observed in the level of fear in any of the 4 dimensions (Table 2). The comparison between the two groups showed the existence of significant differences in all the dimensions (i.e. intrapersonal, procedural, interpersonal and environmental).

Differences in the scores for each dimension of the CMFS-R.

| CG Mean (SD) | 95% CI | IG Mean (SD) | 95% CI | T-test (independent simples) P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor I. Intrapersonal (scoring range = 0−8 points) ITEMS: I am afraid of (1) hurting myself, (4) seeing blood come out of me, (8) throwing up (10) what I will say when I hurt. | Pre | 2.72 (2.384) | 1.99; 3.45 | 2.67 (2.408) | 1.93; 3.42 | 0.928 |

| Post | 3.19 (2.4629 | 2.43; 3.94 | 1.81 (2.185) | 1.14; 2.49 | 0.008 | |

| Diff. (pre-post) | 0.47 (1.932) | −0.13; 1.06 | −0,86 (2.019) | −1.48; −0,24 | 0.003 | |

| Factor II. Procedural (scoring range = 0−10 points) ITEMS: I am afraid of (2) going to the doctor’s office (3) getting a shot (6) having my finger stuck (14) having the doctor or nurse look down my throat (17) the doctor or nurse putting a tongue blade in my mouth. | Pre | 2.81 (2.491) | 2.05; 3.58 | 3.53 (2.501) | 2.77; 4.3 | 0.184 |

| Post | 3.37 (2.664) | 2.55; 4.19 | 2.79 (2.713) | 1.96; 3.63 | 0.319 | |

| Diff. (pre-post) | 0.56 (2.271) | −0.14; 1.26 | −0.74 (2.381) | −1.48; −0.01 | 0.011 | |

| Factor III. Environmental (scoring range = 0−8 points) ITEMS: I am afraid (5) going to the hospital (11) if I went to the hospital, I would have to stay a long time (13) I might die if I go to the hospital (16) being away from my family if I go to the hospital | Pre | 3.47 (2.520) | 2.69; 4.24 | 4.02 (2.454) | 3.27; 4.78 | 0.301 |

| Post | 3.98 (2.425) | 3.23; 4.72 | 3.05 (2.786) | 2.19; 3.9 | 0.102 | |

| Diff. (pre-post) | 0.51 (1.818) | −0.05; 1.07 | −0.98 (2.262) | −1.67; −0.28 | 0.001 | |

| Factor IV. Interpersonal (scoring range = 0−8 points) ITEMS: I am afraid (7) the doctor and nurse will not tell me what they are going to do to me (9) missing school if I’m sick (12) my friends/family will catch something I have if I’m sick and play with them (15) the nurse or doctor will tell me something is wrong with me | Pre | 2.42 (2.393) | 1.68; 3.15 | 2.33 (1.911) | 1.74; 2.91 | 0.843 |

| Post | 2.72 (2.271) | 2.02; 3.42 | 1.7 (2.346) | 0.98; 2.42 | 0.043 | |

| Diff. (pre-post) | 0.3 (1.921) | −0.29; 0.89 | −0.63 (2.236) | −1.32; 0.06 | 0.042 |

CG: Control group; IG: Intervention group; Pre: Pre-intervention measure; Post: Post-intervention measure.

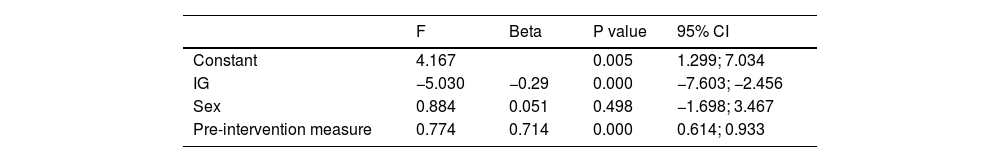

Considering the above results, a multiple linear regression analysis was performed to determine the relationship between the post-intervention measure (CMFS-R score) and the independent variable (CG vs. IG). The coefficient of determination (R²) for the model was 0.563, indicating that 56.3% of the variability in the dependent variable can be explained by the independent variables included in the model. The p-value for the regression model was significant (p < 0.001). And it was observed that only the variable sex did not contribute significantly to the prediction of the dependent variable (Table 3).

DiscussionThis study aimed to evaluate whether carrying out an intervention that involved interactions within a simulated health care space would reduce medical fear among children. The Health-Friendly Program has developed an innovative intervention compared to currently known measures to tackle medical fear among children. In fact, different methods have been described to address children’s fears, at preschool and school ages, related to clinical environments. Actions to reduce these fears include decorating spaces with children’s motifs, the use of music and colorful uniforms among health care professionals and experiences with clowns,29 which will doubtlessly pay off regarding children’s physical and psychological well-being.2,9

Many of these interventions have not been evaluated objectively, and if they are assessed, the results are disparate. For example, Gutierrez Cantó29 evaluated visits from clowns before children undergo surgery, but no significant differences in fear reduction were identified. Similarly, Meisel30 found that the clown intervention was not effective in reducing psychological discomfort among children before surgery. Studies were even suggested to identify a suitable child profile for interventions with clowns.30 In the Oncohematology Unit, visits from clowns helped control the fear response before a painful medical procedure, but only during children’s interactions with the clowns and not with all the measurement scales used.31

Few interventions are intended to reduce fear among children preventively, in other words, long before they come into direct contact with health care services. By recreating various medical scenarios, the Health-Friendly Program allowed children to interact with various materials, situations and simulated patients and nurses. The results showed that participation in this program reduced medical fear in children aged 6 years. The intervention group thereby demonstrated a clear drop in the level of medical fear (pre–post difference = −3.21 (6.505)), and the difference between the groups was statistically significant. Therefore, we can state that contact with a simulated health care space was effective in reducing the perception of fear caused by the health care environment. Additionally, the multiple linear regression analysis revealed that 56.3% of the variability in the post-intervention CMFS-R score can be explained by the independent variable included in the model (CG vs. IG). This finding suggests that more than half of the variability in the reduction of medical fear levels is attributable to exposure to the Health-Friendly Program. Given the complexity and multitude of factors influencing human behavior and outcomes, this level of explained variance is considerable. However, comparable studies employing similar analyses were not identified, limiting the ability to contextualize this result.

As explained before, similar programs have been evaluated, such as the “Teddy Bear Hospital”12,13 or the “Teddy Bear Clinic Tour”.6 However, their evaluation focused on fear of specific medical procedures, such as needle pain.6 Other experiences refer to tours through hospital units or spaces where the child will spend time during their hospital stay or surgery, allowing them to ask questions and giving them a detailed look not only at the spaces but also at the equipment.19–21 In this case, the aim is also specific, particularly focusing on presurgery anxiety.20,21 Furthermore, these measures are intended for hospitalized children or children who are going to undergo surgery19 and thus leave out other medical environment fields such as outpatient care. However, children often visit outpatient facilities, which can play an important role in the development of their medical fear.6 It should also be highlighted that research related to these measures has focused generally on anxiety and rarely on fear.13,29,31

The intervention described in our study incorporates outpatient care through nurse consultations and childhood check-ups, simulating procedures such as vaccinations or throat examinations. Our intervention also incorporates effective techniques for psychologically preparing children for surgery and admission to the hospital, such as by providing information, promoting therapeutic play and teaching confrontation skills.19

Fear can increase when confronting an unknown place, people and materials2; therefore, it could be argued that prior contact with a simulated and recreated environment that presents the equipment and allows children to become familiar with it may help lessen this fear. The detailed analysis of each of the scale’s dimensions suggests that our intervention is effective in addressing these aspects, as the participants in the IG reported a reduction in fear levels in all the dimensions (intrapersonal, procedural, interpersonal and environmental fears), showing a statistically significant pre–post difference.

One unexpected result was the increase in the level of medical fear in the CG in the postintervention measure. One possible explanation could be that in the CMFS-R, children were asked about situations that they might not have considered before (for example, “I am afraid I might die if I go to the hospital”). Therefore, it could be argued that the second time the children answered the CMFS-R, they were more aware of their fears. However, this increased level of fear could have been neutralized, as they participated in the Health-Friendly Program one week after the postintervention assessment.

Medical fear experienced by children during health visits or hospitalization is related to negative patient outcomes, such as an increase in the pain level, a delay in recovery or a greater likelihood of infection.7 Furthermore, the literature suggests that this phenomenon can have short- and long-term consequences.6,8,9 The intervention presented here has proven to be an effective measure that, as a complement to the education offered at school, may help alleviate negative emotional responses in children during contact with health care services and professionals. It thereby has the potential to improve children’s experiences during health follow-ups or when they require medical care, which could improve patient outcomes in the long run.

The Health-Friendly Program can be extended to other fields, cultures, environments and population groups. Among the various proposals to attempt to reduce medical fear, as described, the vast majority are aimed at the child population. However, older children also experience fear, and an intervention such as the one described in the study can be adapted in terms of content and language for older age groups.

In terms of methodology, this study had some potential limitations. It would have been interesting to analyze other variables that may have some influence on the perception of medical fear, such as previous experiences in health care settings or the presence of health care professionals in the family unit. However, it was not possible to collect these data in our study, since the only source of information was the children themselves (no information was collected from parents or teachers) and given their young age, the confirmation of certain data would possibly have been more difficult. Another potential limitation is the lack of assessment of the medium-term effects of the Health-Friendly Program. Undoubtedly, this would have been desirable, but due to the tight schedule of the present research project, it was not possible. Extending the follow-up period to at least 6 or 12 months would have allowed for a more thorough assessment of the intervention's long-term effects. Both issues should be taken into consideration when planning further studies in this area. For future studies, we recommend widening the age range to assess the effectiveness of the intervention in other pediatric age groups. The intervention might also require adaptation (scenarios and dialogs) to different cultural contexts. Moreover, the assessment of additional variables and supplementary statistical analysis such us linear regression or multivariate analysis could be applied in future evaluations of the Program.

ConclusionThe Health-Friendly Program provides an innovative intervention to reduce medical fear among children based on information, confrontation strategies and health care simulation scenarios.

The difficulty for children in accessing the hospital environment, or the effort, preparation and dedication required from medical staff during childcare, might demonstrate the beneficial alternative offered by simulated health care spaces to reduce medical fear among young children, such as the intervention in this study.

These results suggest the potential benefit of incorporating educational interventions in schools in collaboration with university and health care simulation centers to improve children's perception of fear in the medical environment.

CRediT authorship contribution statementNelia Soto-Ruiz: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Paula Escalada-Hernández: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Cristina García-Vivar: Supervision, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Marta Ferraz-Torres: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Amaia Saralegui-Gainza: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing Leticia San Martín-Rodríguez: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

FundingThis work was supported by the Department of Education of the Government of Navarre (Grant No. CENEDUCA4/2019). Open Access funding provided by Universidad Pública de Navarra (UPNA).

The authors declare no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

The authors are grateful to the schools and parents for supporting this study and they thank the children for their valuable collaboration in the Health-Friendly Programme.