A 2-year old girl visited the clinic with a right preauricular mass. Prior to this, she was healthy, with no medical history of interest and had received all her immunisations. Her parents are from Ecuador and her father had tuberculosis which was treated correctly 10 years ago. Examination revealed a soft, tender mass in the parotid gland measuring 0.5cm in diameter and high fever at the onset of symptoms. Viral parotitis was suspected and therefore blood tests were ordered, which were negative. Anti-inflammatory drugs were prescribed for one week. Twenty days after onset, the lesion had increased in size with signs of inflammation. Ultrasound images showed a multilocular lesion measuring 25mm in diameter in the right parotid gland and lateral cervical and mastoid adenopathies suggestive of an inflammatory process with abscess. Antibiotic therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid was commenced, with no response after 7 days. A broader study was therefore recommended. The Mantoux test was positive (12mm) at 48h. A QuantiFERON test was performed, which was negative. An ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy was performed and the specimen culture was positive for Mycobacterium malmoense. Treatment with isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol and clarithromycin was started.

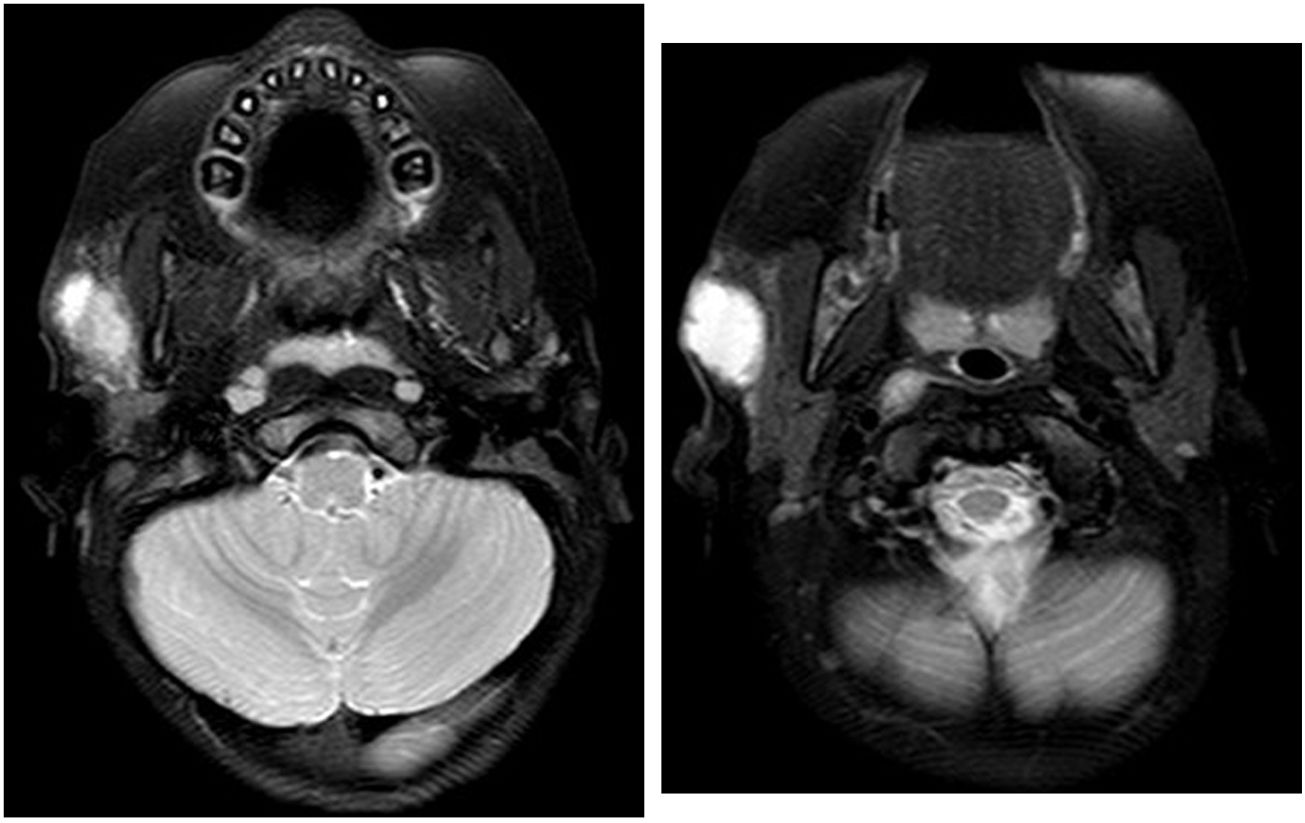

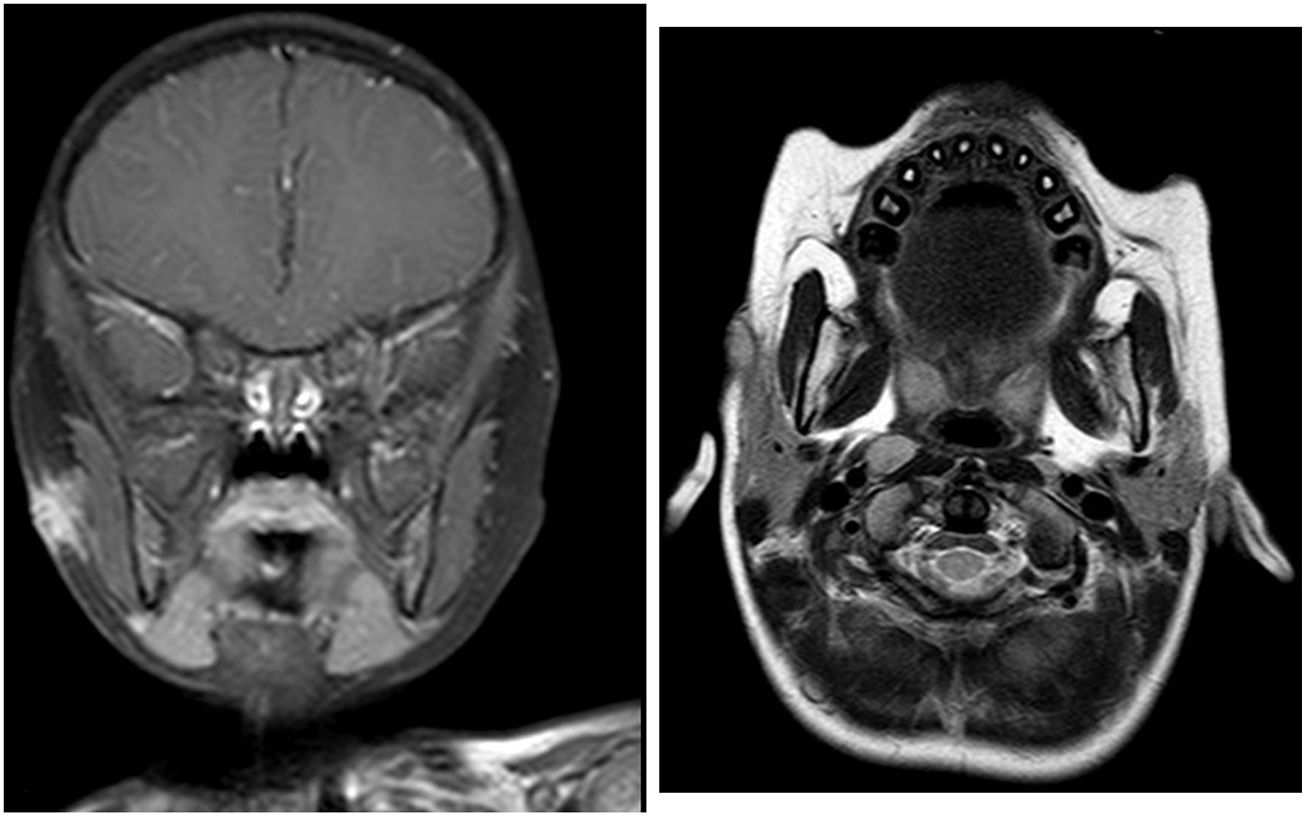

The lesion was confirmed by MR imaging (Figs. 1 and 2). The lesion was drained and its size decreased to 0.3cm in diameter after three months of treatment. After 9 months of treatment, the lesion was stable and was surgically removed (Figs. 3 and 4).

T1 and T2-sequences with gadolinium: change in signal intensity at the anterior pole of the parotid gland compared to subcutaneous lesion with no clear path of the fistula. Compared to the initial study, there is significant improvement with a reduction in lesion size and signal intensity.

An intraparotid lymph node was resected, showing chronic granulomatous inflammation and parotid parenchyma with interstitial fibrosis. The surgery was completed without complications.

DiscussionCervical lymphadenitis is the most common manifestation of infection due to non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) in children, affecting children under the age of 5 years with no associated comorbidites.1–3 Parotid gland involvement is uncommon.

Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex is the most prevalent pathogen.2,4,5 In northern Europe, M. malmoense is one of the most prevalent NTM.6 The mechanism of transmission of NTM remains unclear.3,4,7

Lesions tend to be unilateral and non-tender, starting subacute but becoming more chronic, and gradually increase in size with fistula formation, although they may heal spontaneously.1–3,8 The differential diagnosis must include bacterial and tuberculous lymphadenitis, and, less commonly, parotid tumours.7

The diagnosis is confirmed by isolating pathogens from specimens obtained by FNA biopsy or excision.3,5,7

Ultrasound imaging is the method of choice; computed tomography (CT) and MRI scans are indicated prior to surgery for large, complicated lesions or to delimit their size.1,5

Mantoux skin test reactions are positive (induration≥10mm) in 30–60% of children with NTM, but this is not very useful for establishing a differential diagnosis with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MT).2,4,5 Nevertheless, interferon gamma release assays (IGRA) are typically negative since most of the NTM involved do not express antigens that induce the tested cellular immune response.2,4,5

Identification of NTM using molecular diagnostic techniques allows rapid isolation of the pathogen, with even ≥90% sensitivity.2,3

Treatment is controversial; there is not enough evidence to prove the superiority of expectant management, drug therapy or surgical intervention.2,8

Combination therapy, including a macrolide antibiotic plus rifabutin, fluoroquinolones or ethambutol,5–8 for a minimum of 6 months is recommended to prevent resistance.

Surgical intervention, which in some studies is considered the treatment of choice,1,5,8,9 is not exempt from complications: superinfection of the surgical site and neurovascular lesions, such as facial nerve paralysis.3,7

Drug therapy before or after surgery may help decrease the size of the excision site, thereby reducing the risk of bilateral brain injury, advanced lesions, fistulisation or recurrence.5,9

Final commentsNTM-related infections of the parotid gland are rare and MT must be ruled out. Treatment must be personalised after assessing the risk-benefit ratio.

In our case, drug therapy prior to surgery considerably reduced the size of the lesion and minimised aesthetic sequelae.

We would like to thank everyone from the Paediatrics, ENT and Microbiology Departments at Hospital de Sant Pau.

Please cite this article as: Juzga-Corrales DC, Moliner-Calderón E, Coll-Figa P, Leon-Vintró X. Infección parotídea por Mycobacterium malmoense. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2019;37:545–547.