To assess teachers’ attitudes and perceptions about preparation of public primary and secondary education schools in the Puerto Real University Hospital (Cádiz, Spain) area to care for students with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM).

MethodsA descriptive observational study where answers to an attitude and perception questionnaire on the preparation of schools to care for pupils with T1DM were analyzed. A total of 765 teachers (mean age, 44.3±8.8 years; 61.7% women) from 44 public schools in the area of the Puerto Real University Hospital were selected by random sampling.

ResultsOverall, 43.2% of teachers surveyed had or had previously had students with T1DM, but only 0.8% had received specific training on diabetes. 18.9% of teachers reported that one of their students with T1DM had experienced at least one episode of hypoglycemia at school, and half of them felt that their school was not prepared to deal with diabetic emergencies. 6.4% stated that their school had glucagon in its first aid kit, and 46.9% would be willing to administer it personally. Women, physical education teachers, and headmasters had a more positive perception of the school than their colleagues. Teachers with a positive perception of school preparation and with a positive attitude to administer glucagon were significantly younger than those with no positive perception and attitude.

ConclusionsThe study results suggest that teachers of public schools in our health area have not been specifically trained in the care of patients with T1DM and perceive that their educational centers are not qualified to address diabetic emergencies.

Evaluar las actitudes y la percepción del profesorado sobre la preparación de los centros públicos de educación infantil, primaria y secundaria del área del Hospital Universitario Puerto Real para atender a alumnos con diabetes tipo 1 (DM1).

MétodosEstudio observacional descriptivo en el que se analizan las respuestas a un cuestionario de actitud y percepción sobre la preparación del centro educativo (17 preguntas) para la atención de los alumnos con DM1 de 765 profesores (edad media: 44,3±8,8 años; 61,7% mujeres) de 44 centros educativos públicos del área del Hospital Universitario Puerto Real (Cádiz, España) seleccionados mediante muestreo aleatorio.

ResultadosEl 43,2% había tenido o tiene actualmente alumnos con DM1 y solo el 0,8% reconoce haber recibido formación sobre diabetes. El 18,9% refería que alguno de sus alumnos con DM1 había experimentado al menos un episodio de hipoglucemia en el colegio (el 42,5% de los profesores que tienen o han tenido alumnos con DM1) y la mitad opinaba que su centro educativo no está capacitado para atender las urgencias diabéticas. El 6,4% refería que su centro dispone de glucagón en su equipo de primeros auxilios y el 46,9% estaría dispuesto a administrarlo personalmente. Las mujeres, los profesores de educación física y los directores mostraron una percepción más positiva del centro educativo con respecto a sus compañeros. Los profesores con percepción positiva de la preparación del centro y con actitud positiva para administrar glucagón eran significativamente más jóvenes que aquellos con percepción y actitud no positiva.

ConclusionesLos resultados del estudio orientan a que los profesores de los centros educativos públicos de nuestra área sanitaria no han sido formados específicamente en la atención a pacientes con DM1 y perciben que sus centros educativos no están capacitados para atender urgencias diabéticas.

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM1) is the second most frequent chronic disease and the most common endocrine-metabolic disorder in childhood, with a very considerable social and healthcare impact.1,2 The management of DM1 requires the daily administration of insulin. In this regard, the studies published by the DCCT Research Group have shown that intensive treatment seeking to optimize glycemic control is able to delay the appearance and reduce the progression of chronic complications in adults and adolescents with DM1.3,4 In order to secure optimum glycemic control, children and adolescents with DM1 require frequent glucose monitoring and the administration of several insulin injections every day (or the use of insulin pumps), as well as adequate adherence to diet and physical activity recommendations, while accepting the considerable likelihood of suffering some hypoglycemic episode. In this regard, recent studies5–7 have reported that diabetic emergencies (hyperglycemia and, especially, hypoglycemia) are quite frequent in the school setting.

Bearing in mind that an average diabetic child spends one-third of the day in educational centers,6 schooling could be a limiting factor for both the implementation of modern treatment protocols and for the detection and rapid correction of acute glycemic decompensation episodes, particularly if such patients do not receive adequate help and/or supervision from the health staff of the educational center (if any) or their teachers during school hours.1,8 Accordingly, guaranteeing the required care of these children and adolescents, who are not yet autonomous as regards the management of their disease, while they are attending their educational centers has become a priority concern for healthcare professionals and others, concerned about their present and future wellbeing and their full social integration.9 However, very little information is currently available in Spain regarding teacher perception as to the degree of preparedness of the educational centers and concerning the attitude of the teachers themselves to helping children and adolescents with DM1,10–12 particularly in the event of diabetic emergencies. The present study was therefore carried out to clarify these aspects in our healthcare setting.

MethodsStudy designA descriptive observational study was carried out to evaluate teacher perceptions and attitudes regarding the preparedness of state infant, primary and secondary educational centers within the recruitment area of Puerto Real University Hospital (Cádiz, Spain) for providing help to pupils with DM1. The study project was presented and approved on 23 July 2013 by the Doctorate Commission of the University of Cádiz.

ParticipantsPuerto Real University Hospital provides healthcare for 300,000 inhabitants in the 11 municipalities of its recruitment area, with 64 state infant and primary educational centers and 41 secondary educational centers. All the teachers in the state infant, primary and secondary educational centers of the recruitment area of Puerto Real University Hospital were regarded as candidates for participation in the study. The exclusion criteria were: employment at a private or a charter school; failure to sign the informed consent; and being on sick leave at the time of the study.

Calculation of sample sizeAfter two samplings (one for the infant and primary educational centers, and another for the secondary centers), stratified (according to geographical setting) for a confidence level of 95%, a statistical power of 80% and assuming a difference between cases and controls of 25%, the calculated minimum required sample size was 24 infant and primary educational centers, and 20 secondary centers, which were randomly selected from 10 different municipalities in the study area.

Study protocolThe 1107 teachers from the 44 educational centers that agreed to participate in the study after reading the information sheet and signing the informed consent were asked to complete two self-administered questionnaires in the presence of the investigators:

- (1)

A questionnaire concerning sociodemographic and educational characteristics. This recorded the following variables: age, gender, years of teaching experience, type of teacher (principal of the center, supervisor, physical education teacher, other teachers), and the presence of pupils with DM1 in the current course or in earlier courses.

- (2)

A questionnaire evaluating teacher attitudes and perceptions regarding the preparedness of the educational center for treating pupils with DM1, adapted from the ones used by Pinelli et al.7 and Amillategui et al.11 (Annex). This questionnaire consisted of 17 questions, of which 13 had three possible answers (yes/no/don’t know or no answer), while the remaining four were open questions or had different answering options (see Annex). A positive teacher perception of the center was defined by an affirmative answer to the question: Do you think your center is capable of controlling diabetic emergencies? In turn, a positive teacher attitude was defined by an affirmative answer to the question: Would you be willing to administer glucagon if needed? Diabetic emergencies were defined as hypoglycemia (glucose<70mg/dl) and hyperglycemia (glucose>300mg/l) occurring during school hours, independently of the presence of associated symptoms. We did not address the incidence of severe hypoglycemic episodes among the pupils with DM1.

After examining the answers to the questionnaires, the investigators excluded 342 teachers from the study due to the following reasons: (1) failure to answer at least 70% of the questions of the questionnaire on attitude: 139 teachers; (2) answering with a repetitive pattern: 28 teachers; (3) failure to correctly provide the information required by the questionnaires: 156 teachers; (4) failure to follow the instructions of the investigators: 19 teachers.

Statistical analysisThe data corresponding to both questionnaires were coded and analyzed using the SPSS version 20.0 statistical package for MS Windows. The descriptive analysis of qualitative variables was performed by calculating frequencies and percentages, while the mean, standard deviation, median and range were determined for quantitative variables. After verifying normal data distribution with the Shapiro–Wilk test, the Student t-test (2 groups) was used to compare quantitative variables between independent groups, while the chi-squared test (or Fisher exact test where indicated) was used to compare qualitative variables between independent groups. The independent variables to be included in the models were selected on the basis of statistical criteria. All significance values refer to two-tailed testing. Statistical significance was considered for p<0.05.

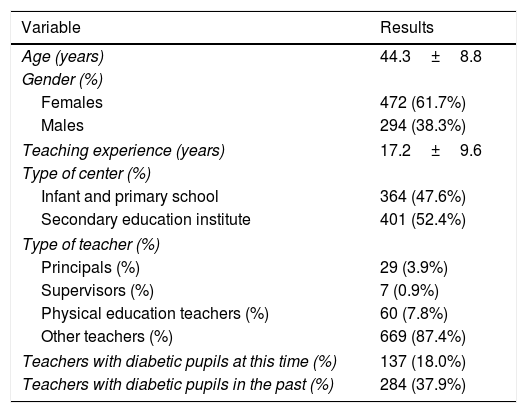

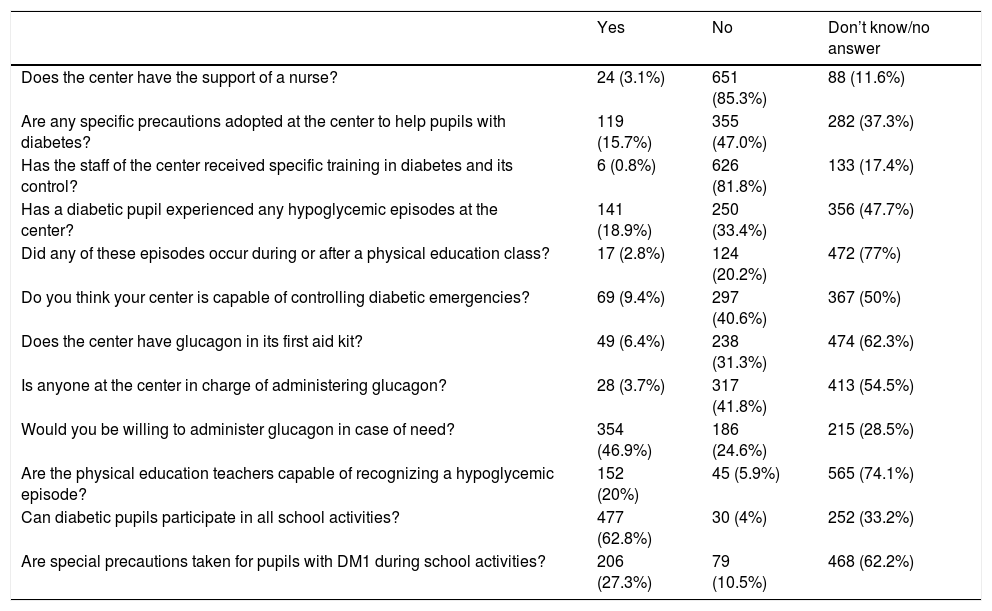

ResultsAn analysis was made of the answers of 765 teachers from 44 public educational centers in the recruitment area of Puerto Real University Hospital to the questionnaires on attitude and perception regarding the preparedness of their educational center to attend to pupils with DM1. As can be seen in Table 1, a total of 18% of the teachers (n=137) reported the presence of pupils with DM1 in their classes, and 37.9% (n=284) claimed to have had such pupils in previous years (43.2% currently or previously had diabetic pupils). Despite the above, only 0.8% had received specific training in diabetes and diabetes control (Table 2).

Characteristics of the teachers included in the study (n=765).

| Variable | Results |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 44.3±8.8 |

| Gender (%) | |

| Females | 472 (61.7%) |

| Males | 294 (38.3%) |

| Teaching experience (years) | 17.2±9.6 |

| Type of center (%) | |

| Infant and primary school | 364 (47.6%) |

| Secondary education institute | 401 (52.4%) |

| Type of teacher (%) | |

| Principals (%) | 29 (3.9%) |

| Supervisors (%) | 7 (0.9%) |

| Physical education teachers (%) | 60 (7.8%) |

| Other teachers (%) | 669 (87.4%) |

| Teachers with diabetic pupils at this time (%) | 137 (18.0%) |

| Teachers with diabetic pupils in the past (%) | 284 (37.9%) |

Answers to the questionnaire evaluating teacher attitudes and perceptions regarding the preparedness of the educational center for treating pupils with diabetes.

| Yes | No | Don’t know/no answer | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Does the center have the support of a nurse? | 24 (3.1%) | 651 (85.3%) | 88 (11.6%) |

| Are any specific precautions adopted at the center to help pupils with diabetes? | 119 (15.7%) | 355 (47.0%) | 282 (37.3%) |

| Has the staff of the center received specific training in diabetes and its control? | 6 (0.8%) | 626 (81.8%) | 133 (17.4%) |

| Has a diabetic pupil experienced any hypoglycemic episodes at the center? | 141 (18.9%) | 250 (33.4%) | 356 (47.7%) |

| Did any of these episodes occur during or after a physical education class? | 17 (2.8%) | 124 (20.2%) | 472 (77%) |

| Do you think your center is capable of controlling diabetic emergencies? | 69 (9.4%) | 297 (40.6%) | 367 (50%) |

| Does the center have glucagon in its first aid kit? | 49 (6.4%) | 238 (31.3%) | 474 (62.3%) |

| Is anyone at the center in charge of administering glucagon? | 28 (3.7%) | 317 (41.8%) | 413 (54.5%) |

| Would you be willing to administer glucagon in case of need? | 354 (46.9%) | 186 (24.6%) | 215 (28.5%) |

| Are the physical education teachers capable of recognizing a hypoglycemic episode? | 152 (20%) | 45 (5.9%) | 565 (74.1%) |

| Can diabetic pupils participate in all school activities? | 477 (62.8%) | 30 (4%) | 252 (33.2%) |

| Are special precautions taken for pupils with DM1 during school activities? | 206 (27.3%) | 79 (10.5%) | 468 (62.2%) |

With regard to diabetic emergencies, 18.9% of those interviewed reported that a pupil with DM1 had suffered at least one hypoglycemic episode in school (42.5% of the teachers who currently or previously had diabetic pupils), and one-half of them considered that their educational center was not prepared for dealing with diabetic emergencies. In this sense, only 6.4% reported that their center had glucagon in its first aid kit (31.3% answered no and the remaining 62.3% did not know or did not answer), and 41.8% considered that there was nobody in the center in charge of administering it. However, in case of need, almost one-half of the teachers (46.9%) claimed to be willing to administer it personally (Table 2).

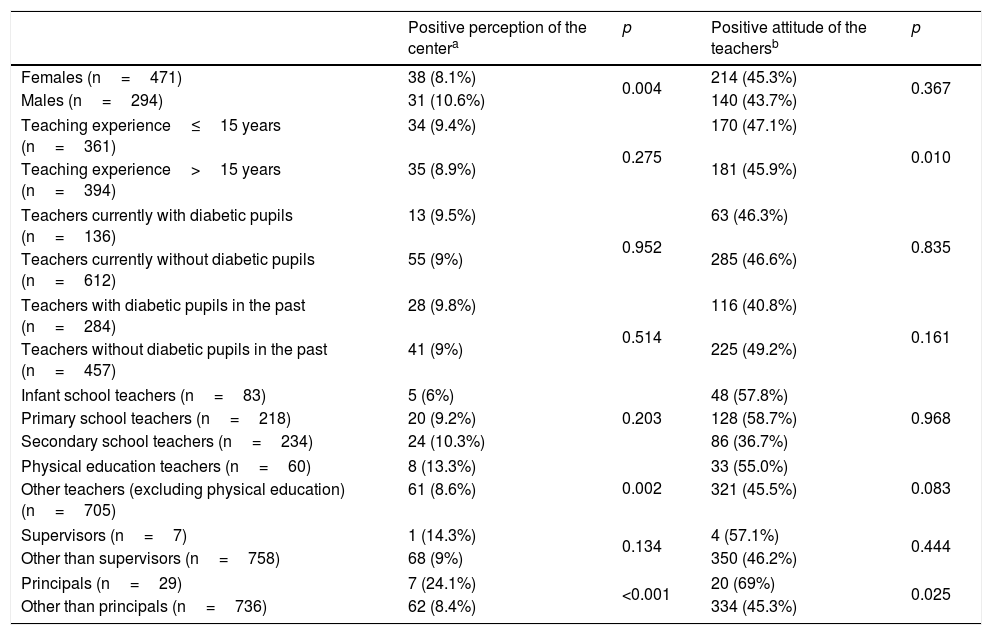

The univariate analysis of the factors associated with positive perception of the center and a positive attitude on the part of the teachers (Table 3) found female teachers, physical education teachers and principals to have a more positive perception of the educational center compared with the rest of their colleagues. In turn, teachers with 15 years of experience or less, and directors, were more inclined to show a positive attitude toward treating diabetic children than teachers with over 15 years of experience or teachers who were not principals. In this sense, the teachers with a positive perception of the preparedness of the center and with a positive attitude toward administering glucagon were significantly younger (43±9.3 years vs 45.5±8.3 years; p=0.032, and 43.3±9.1 years vs 45.4±8.2 years; p=0.006, respectively) than those with no such positive perception or attitude. We observed no differences in positive perception of the center or in positive attitude on the part of the teachers according to whether the latter had pupils with DM1 in their classes either currently or in the past (Table 3).

Univariate analysis of the positive attitudes and perceptions of the teachers.

| Positive perception of the centera | p | Positive attitude of the teachersb | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females (n=471) | 38 (8.1%) | 0.004 | 214 (45.3%) | 0.367 |

| Males (n=294) | 31 (10.6%) | 140 (43.7%) | ||

| Teaching experience≤15 years (n=361) | 34 (9.4%) | 0.275 | 170 (47.1%) | 0.010 |

| Teaching experience>15 years (n=394) | 35 (8.9%) | 181 (45.9%) | ||

| Teachers currently with diabetic pupils (n=136) | 13 (9.5%) | 0.952 | 63 (46.3%) | 0.835 |

| Teachers currently without diabetic pupils (n=612) | 55 (9%) | 285 (46.6%) | ||

| Teachers with diabetic pupils in the past (n=284) | 28 (9.8%) | 0.514 | 116 (40.8%) | 0.161 |

| Teachers without diabetic pupils in the past (n=457) | 41 (9%) | 225 (49.2%) | ||

| Infant school teachers (n=83) | 5 (6%) | 0.203 | 48 (57.8%) | 0.968 |

| Primary school teachers (n=218) | 20 (9.2%) | 128 (58.7%) | ||

| Secondary school teachers (n=234) | 24 (10.3%) | 86 (36.7%) | ||

| Physical education teachers (n=60) | 8 (13.3%) | 0.002 | 33 (55.0%) | 0.083 |

| Other teachers (excluding physical education) (n=705) | 61 (8.6%) | 321 (45.5%) | ||

| Supervisors (n=7) | 1 (14.3%) | 0.134 | 4 (57.1%) | 0.444 |

| Other than supervisors (n=758) | 68 (9%) | 350 (46.2%) | ||

| Principals (n=29) | 7 (24.1%) | <0.001 | 20 (69%) | 0.025 |

| Other than principals (n=736) | 62 (8.4%) | 334 (45.3%) | ||

According to the criteria of the American Diabetes Association, schools should offer diabetic children and adolescents a safe environment from the healthcare perspective, allowing the application of the most effective treatments for diabetes control, and facilitating the full participation of these patients in both school and out of school activities.1,2,13 In order for this to be possible, it is essential for the teachers and health professionals of the schools to receive special training in diabetes,14 since this would help them to understand certain attitudes and behavior on the part of diabetic children; to contribute to the reinforcement of healthy habits and adherence to glycemic control and to medically prescribed treatments; and even to collaborate in detecting and resolving blood glucose decompensation episodes.15–17 Likewise, diabetic pupils would benefit from increased knowledge on the part of their teachers, since they would experience less anxiety in situations requiring help, knowing that their teachers were trained in the illness. In our area, although 43.2% of the teachers acknowledged having pupils with DM1 in their classes either currently or in the past, very few of them had received specific training in diabetes (only 0.8% of those interviewed). In this regard, the health authorities of some Spanish Autonomous Communities9 have established specific diabetes training plans for professionals at educational centers, which we hope will contribute to correcting the existing lack of information among teachers in state schools regarding the management of diabetic children and adolescents.

Hypoglycemia deserves special mention in view of the potential seriousness of the condition and the fact that it affects 63–75% of all children with DM1 during school hours,5–7 the frequency of such episodes increasing the lower the patient age.6 In this respect, Bodas et al.6 examined the perceptions of children and adolescents with DM1 (6–16 years of age) enrolled in a total of 18 summer camps in 10 Spanish Autonomous Communities. Thirty-six percent of the subjects claimed to have experienced at least one severe hypoglycemic episode. The reaction of the center (multiple response questions) in such cases was to call the parents (65%), administer sugar or juice via the oral route (21%), inject glucagon (15%), or call the emergency service (13%). It should be noted in this study that the majority of the children (87%) were of the opinion that the teachers should receive written instructions about the symptoms and the steps to be taken in the event of hypoglycemia, as well as more information on diabetes in general (63%).6 Another aspect to be taken into account is the absence of glucagon in the first aid kits of many educational centers.6 In turn, most teachers are unaware of the presence of the medication at the center. These findings were recorded not only in our study but also in other studies, both national11,12 and international.7,18

Only 9.4% of the teachers interviewed in our study considered their educational center to be capable of dealing with diabetic emergencies. The lack of training in dealing with such emergencies; the possible legal consequences of an unfortunate intervention; the lack of material resources (such as glucagon in the first aid kit); and the lack of reference healthcare staff at the center or at nearby facilities are factors that probably help explain this low affirmative response rate. Despite these limitations, a somewhat surprising percentage of teachers would be willing to personally administer glucagon in case of need (46.9%). This suggests that although the perception among the teachers regarding the preparedness of the center is not particularly positive, they have a strong willingness to collaborate in the management of pupils with DM1, despite their lack of specific training.

Our study is not without limitations. Firstly, the private and charter schools in our area were omitted. As a result, our findings cannot be extrapolated to these centers or to other geographical areas. Secondly, since the study explored attitudes and perceptions among teachers, the answers to some of the questions were very likely conditioned by whether or not the teachers had current or past personal experience with diabetic pupils. In turn, the incidence of the reply “don’t know/no answer” exceeded 50% for some questions. Lastly, since our study was exclusively targeted to the teaching staff, the results obtained for some questions (such as those referring to pupils with hypoglycemic episodes or the availability of glucagon in the center) markedly underestimate the real situation. This agrees with the observations of other similar studies in which pupil and parent answers to certain questions exceeded those of the teaching staff.6,7,11 We could not confirm this circumstance in our study, however, since the parents of diabetic pupils were not interviewed. In conclusion, the teachers of the state educational centers in our healthcare area consider that they have not been specifically trained in the care of patients with DM1, and regard their educational center as not being capable of dealing with diabetic emergencies. The public authorities should be advised to implement specific training programs in diabetes targeted at teachers and infant, primary and secondary educational centers, along with an evaluation of the need to upgrade the available human and material resources in order to ensure the adequate care of pupils with DM1.

Conflict of interestThe authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

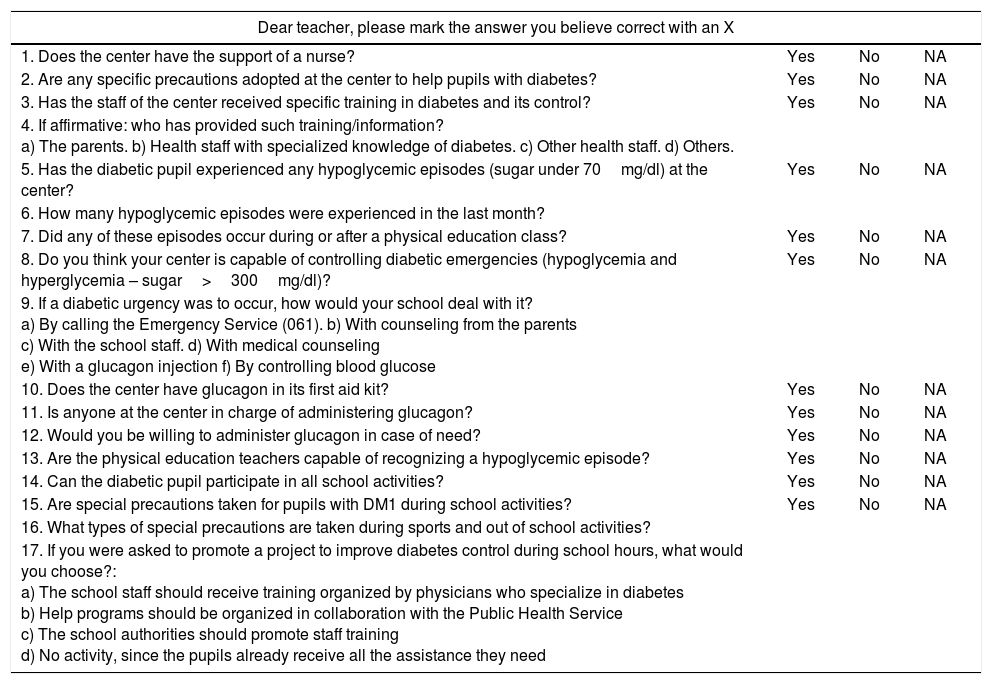

Questionnaire on teacher attitudes and perceptions regarding the preparedness of the educational center for treating diabetic pupils (adapted from Pinelli et al.7 and Amillategui et al.11)

| Dear teacher, please mark the answer you believe correct with an X | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Does the center have the support of a nurse? | Yes | No | NA |

| 2. Are any specific precautions adopted at the center to help pupils with diabetes? | Yes | No | NA |

| 3. Has the staff of the center received specific training in diabetes and its control? | Yes | No | NA |

| 4. If affirmative: who has provided such training/information? a) The parents. b) Health staff with specialized knowledge of diabetes. c) Other health staff. d) Others. | |||

| 5. Has the diabetic pupil experienced any hypoglycemic episodes (sugar under 70mg/dl) at the center? | Yes | No | NA |

| 6. How many hypoglycemic episodes were experienced in the last month? | |||

| 7. Did any of these episodes occur during or after a physical education class? | Yes | No | NA |

| 8. Do you think your center is capable of controlling diabetic emergencies (hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia – sugar>300mg/dl)? | Yes | No | NA |

| 9. If a diabetic urgency was to occur, how would your school deal with it? a) By calling the Emergency Service (061). b) With counseling from the parents c) With the school staff. d) With medical counseling e) With a glucagon injection f) By controlling blood glucose | |||

| 10. Does the center have glucagon in its first aid kit? | Yes | No | NA |

| 11. Is anyone at the center in charge of administering glucagon? | Yes | No | NA |

| 12. Would you be willing to administer glucagon in case of need? | Yes | No | NA |

| 13. Are the physical education teachers capable of recognizing a hypoglycemic episode? | Yes | No | NA |

| 14. Can the diabetic pupil participate in all school activities? | Yes | No | NA |

| 15. Are special precautions taken for pupils with DM1 during school activities? | Yes | No | NA |

| 16. What types of special precautions are taken during sports and out of school activities? | |||

| 17. If you were asked to promote a project to improve diabetes control during school hours, what would you choose?: a) The school staff should receive training organized by physicians who specialize in diabetes b) Help programs should be organized in collaboration with the Public Health Service c) The school authorities should promote staff training d) No activity, since the pupils already receive all the assistance they need | |||

NA: Don’t know/No answer.

Please cite this article as: Carral San Laureano F, Gutiérrez Manzanedo JV, Moreno Vides P, de Castro Maqueda G, Fernández Santos JR, Ponce González JG, et al. Actitudes y percepción del profesorado de centros educativos públicos sobre la atención a alumnos con diabetes tipo 1. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2018;65:213–219.