To evaluate in the elderly diabetic patient the probability of improving the frailty after performing strength exercises with an elastic band and aerobic exercise.

MethodsProspective study of diabetic patients older than 70 years, with Barthel >80 points and Global Deterioration Scale-Functional Assessment Staging <3 points. Strength exercises with an elastic band 3 days a week and walk 30min a day 5 days a week were recommended. Adherence to the exercises was assessed using the Haynes–Sacket test. Frailty was assessed by the Fried criteria and functional capacity by the short physical performance battery at baseline and at 6 months.

Results44 Patients completed 6 months of follow-up. There was non-adherence to aerobic exercises in 38.6% of cases and to exercises with elastic bands in 47.7%. The prevalence of frailty decreased from an initial 34.1% to 25% at 6 months (p=0.043) and the percentage of patients with a moderate-severe functional limitation was reduced from 26.2% to 21.4% (p=0.007). Adherence to aerobic exercises (p=0.034) and absence of coronary ischemic heart disease (p=0.043) predisposed to improve frailty.

ConclusionsPerforming 6-month strength exercises with an elastic band and aerobic exercise reduces the prevalence of frailty in elderly diabetic patients. The probability of improving frailty decreases in case of coronary ischemic heart disease and increases with adherence to aerobic exercises.

Evaluar en el paciente diabético anciano la probabilidad de mejorar la fragilidad tras realizar ejercicios de fuerza con una banda elástica y ejercicio aeróbico.

MétodosEstudio prospectivo de pacientes diabéticos mayores de 70 años, con Barthel >80 puntos y Global Deterioration Scale-Functional Assessment Staging <3 puntos. Se recomendaron ejercicios de fuerza con una banda elástica 3 días a la semana y caminar 30min al día 5 días a la semana. Se revisó la adherencia a los ejercicios mediante la pregunta de Haynes-Sacket. En el momento basal y a los 6 meses se evaluaron la fragilidad según los criterios de Fried y la capacidad funcional mediante el Short Physical Performance Battery.

ResultadosUn total de 44 pacientes completaron los 6 meses de seguimiento. Se produjo falta de adherencia a los ejercicios aeróbicos en el 38.6% de los casos y a los ejercicios con bandas elásticas en el 47,7%. La prevalencia de fragilidad disminuyó del 34,1% inicial al 25% a los 6 meses (p=0,043), y el porcentaje de sujetos con una limitación funcional moderada-grave se redujo del 26,2 al 21,4% (p=0,007). La adherencia a los ejercicios aeróbicos (p=0,034) y la ausencia de cardiopatía isquémica coronaria (p=0,043) predispusieron a mejorar la fragilidad.

ConclusionesRealizar durante 6 meses ejercicios de fuerza con una banda elástica y ejercicio aeróbico reduce la prevalencia de fragilidad en pacientes diabéticos ancianos. La probabilidad de mejorar la fragilidad disminuye en caso de cardiopatía isquémica coronaria y aumenta con la adherencia a los ejercicios aeróbicos.

Frailty is a multidimensional syndrome affecting mobility, nutritional status, mental health – cognitive ability, and is the consequence of a decrease in physiological reserve and in resistance to stress factors.1 The prevalence of frailty in the elderly population in Spain is between 8.4% and 16.9%,2 and increases with age and among women.3 The disorder is observed in 25% of all elderly patients with diabetes.4 The Di@bet.es study found the prevalence of diabetes in individuals over 75 years of age to be 30.7% in males and 33.4% in females.5 Frailty in diabetic patients increases the likelihood of complications,6 functional impairment,7,8 and mortality.9 Hence, the International Diabetes Federation recommends screening for frailty in all diabetic individuals over 70 years of age, with multidisciplinary assessment of these patients.10

The management of elderly diabetic subjects includes nutritional planning, physical exercise and antidiabetic drugs.11 With regard to physical exercise, a program integrating muscle strength, aerobic resistance and balance exercises is the most appropriate strategy for reducing falls and improving mobility, balance and muscle strength in frail elderly patients.12 In the LIFE study, a structured physical activity program involving these elements was seen to reduce the inability to walk 400m in less than 15min without sitting or the help of others by 18% over 2.6 years of follow-up in vulnerable older adults, compared with an education-only program. This benefit was maintained in the subgroup of patients with diabetes.13 However, there is a lack of studies specifically conducted in frail elderly diabetic patients designed to assess the capacity of physical exercise to reduce the frailty criteria in these individuals.

The objective of the present study in elderly diabetic patients was to assess the probability of improving frailty according to the Fried criteria14 after 6 months of strength exercises with an elastic band three days a week, and 30-min walks 5 days a week.

MethodsStudy design. Inclusion criteriaA non-randomized, prospective cohort follow-up study was carried out. The inclusion criteria were type 2 diabetic patients over 70 years of age of either gender seen at the Endocrinology outpatient clinic of Hospital Dr. José Molina Orosa or the Geriatrics clinic of Hospital Insular de Lanzarote (Spain), with a Barthel score of >80 points15 and a Global Deterioration Scale-Functional Assessment Staging (GDS-FAST) score of <3 points.16 All patients received an information sheet concerning the study and gave their written consent. The study protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee.

Evaluation of frailty and functional capacityPatient follow-up comprised three visits: a first or baseline visit, an intermediate visit after three months, and a final visit after 6 months. The following diagnostic procedures were carried out at the baseline visit:

- -

A detailed case history was compiled and a physical examination made. Questions were asked about microvascular or macrovascular complications, smoking habit and drugs used. Body weight, height, waist circumference and blood pressure were measured. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight divided by squared height.

- -

Laboratory tests were performed to measure glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c), high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c), triglycerides, 25-OH-vitamin D, the glomerular filtration rate, and the isolated urine albumin/creatinine ratio. The antidiabetic drugs were adjusted during the follow-up months when HbA1c was seen to be off-target (objectives: <7.5% for non-frail patients and <8.5% for frail patients).

- -

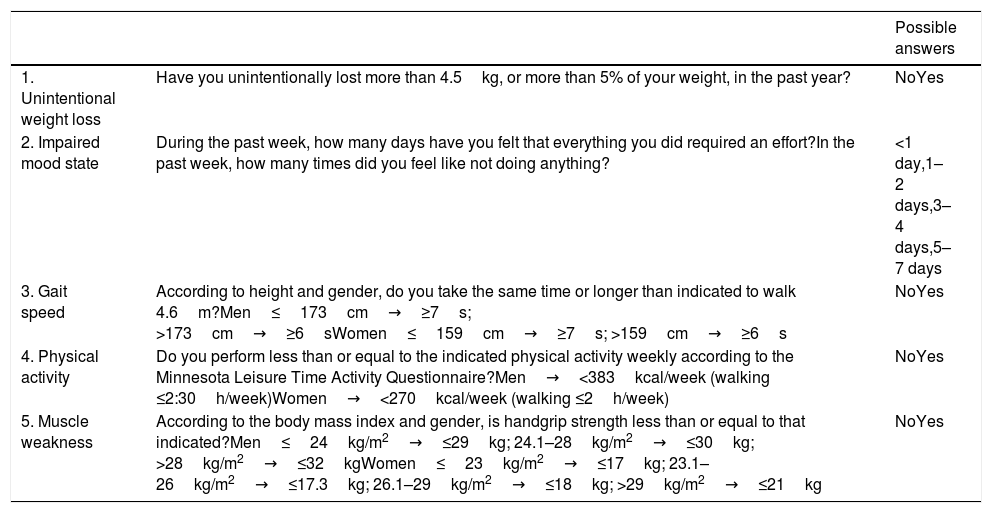

A frailty assessment was carried out according to the Fried criteria (Table 1), with the validated normative values of gait speed and grip strength in the Spanish population being assumed.17 Muscle strength was measured using Jamar and Camry dynamometers. The time taken to walk 4.6m was measured using a Casio chronometer.

Table 1.Fried criteria.

Possible answers 1. Unintentional weight loss Have you unintentionally lost more than 4.5kg, or more than 5% of your weight, in the past year? NoYes 2. Impaired mood state During the past week, how many days have you felt that everything you did required an effort?In the past week, how many times did you feel like not doing anything? <1 day,1–2 days,3–4 days,5–7 days 3. Gait speed According to height and gender, do you take the same time or longer than indicated to walk 4.6m?Men≤173cm→≥7s; >173cm→≥6sWomen≤159cm→≥7s; >159cm→≥6s NoYes 4. Physical activity Do you perform less than or equal to the indicated physical activity weekly according to the Minnesota Leisure Time Activity Questionnaire?Men→<383kcal/week (walking ≤2:30h/week)Women→<270kcal/week (walking ≤2h/week) NoYes 5. Muscle weakness According to the body mass index and gender, is handgrip strength less than or equal to that indicated?Men≤24kg/m2→≤29kg; 24.1–28kg/m2→≤30kg; >28kg/m2→≤32kgWomen≤23kg/m2→≤17kg; 23.1–26kg/m2→≤17.3kg; 26.1–29kg/m2→≤18kg; >29kg/m2→≤21kg NoYes Frailty is diagnosed if the patient meets three or more criteria, and pre-frailty if the patient meets one or two criteria.

- -

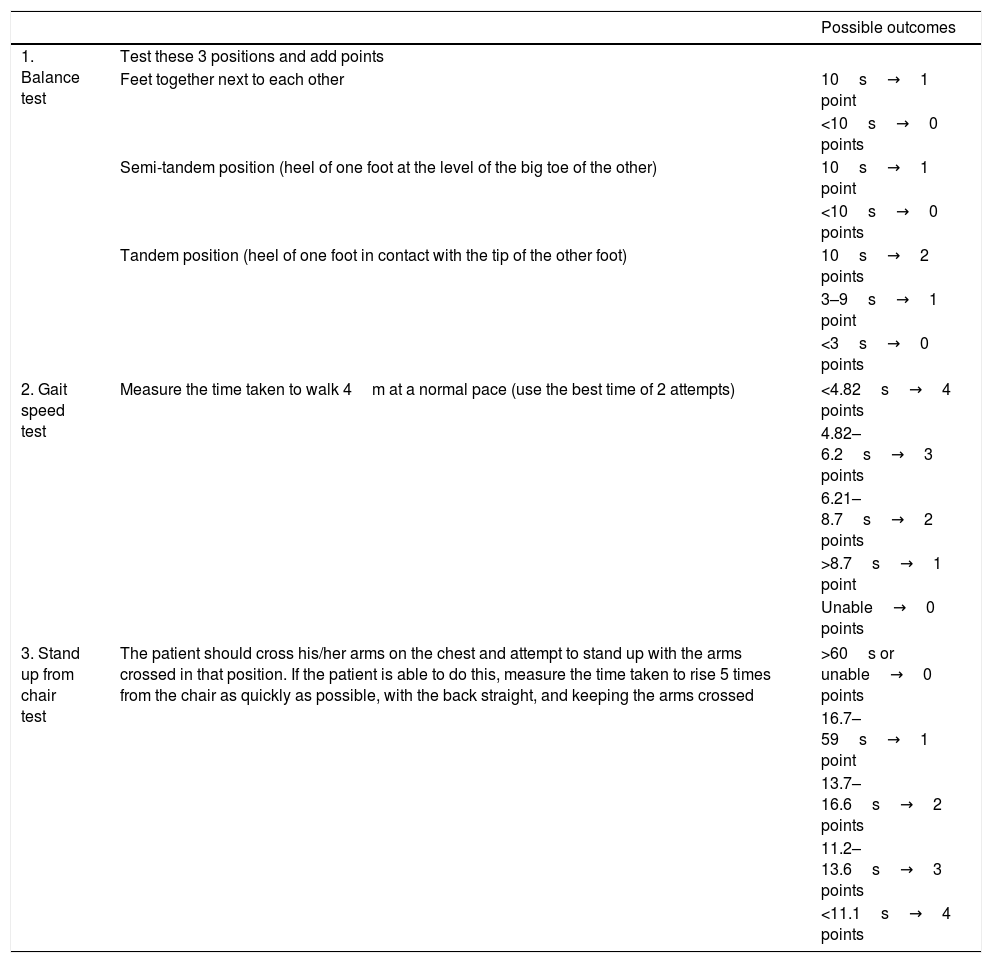

Assessment of functional capacity using the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB, Table 2).18

Table 2.Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB).

Possible outcomes 1. Balance test Test these 3 positions and add points Feet together next to each other 10s→1 point <10s→0 points Semi-tandem position (heel of one foot at the level of the big toe of the other) 10s→1 point <10s→0 points Tandem position (heel of one foot in contact with the tip of the other foot) 10s→2 points 3–9s→1 point <3s→0 points 2. Gait speed test Measure the time taken to walk 4m at a normal pace (use the best time of 2 attempts) <4.82s→4 points 4.82–6.2s→3 points 6.21–8.7s→2 points >8.7s→1 point Unable→0 points 3. Stand up from chair test The patient should cross his/her arms on the chest and attempt to stand up with the arms crossed in that position. If the patient is able to do this, measure the time taken to rise 5 times from the chair as quickly as possible, with the back straight, and keeping the arms crossed >60s or unable→0 points 16.7–59s→1 point 13.7–16.6s→2 points 11.2–13.6s→3 points <11.1s→4 points Severe limitation corresponds to 0–3 points, moderate to 4–6 points, mild to 7–9 points, and minimum limitation to 10–12 points.

At the baseline visit, aerobic (walking 30min a day, 5 days a week) and muscle strength exercises (3 days a week) were prescribed. A medium resistance Thera-Band elastic band requiring 1.8kg of force to reach 100% elongation was provided, together with a document with an illustrated explanation of each exercise. At the baseline visit, the investigators performed a demonstration of the exercises in front of the patient, so that the latter could see how they should be done and clarify any doubts. The 7 recommended muscle strength exercises are described below (each performed in three series of 10 repetitions with each limb, with no predetermined time limit and in the standing position in all cases, except the last exercise):

- -

Flexion – extension of the shoulder. One end of the band is grasped with the foot, the other end is grasped with the ipsilateral hand, and the ipsilateral arm is raised upward and forward.

- -

Abduction – adduction of the shoulder. One end of the band is grasped with the foot, the other end is grasped with the ipsilateral hand, and the ipsilateral arm is raised upward and outwards, with an amplitude of 90°.

- -

Outwards mobilization of the forearms. With the elbows held against the body, the ends of the band are grasped with the hands, and the band is elongated from the center outwards as far as possible.

- -

Inwards mobilization of the forearms. With the elbow held against the body, a vertical axis on one side and one end of the band attached to this axis at hand level, the other end of the band is grasped with the hand ipsilateral to the axis and is elongated from outwards toward the body.

- -

Mobilization of the legs. With one hand holding onto a chair, the band is placed around the ankles with a knot, and the leg is directed stretched out forwards, to one side and backwards.

- -

Flexion of the quadriceps. With both hands holding onto a chair and facing toward the chair, the band is placed around the ankle, the heel is moved toward the ipsilateral gluteal muscle, followed by a return to the starting position.

- -

Extension of the quadriceps. Sitting at the edge of a chair, the band is placed around the ankle, the leg is stretched forwards, followed by a return to the starting position.

Adherence to the exercises was evaluated after 3 and 6 months using the Haynes–Sacket test question addressed to the patients and the persons accompanying them at the clinic: “Some patients may have difficulties performing the strength and walking exercises I recommended. Are you also having difficulties with these exercises?”.19 All the initially assessed parameters were again measured after 6 months.

Statistical analysisThe changes over 6 months in the percentages of patients with frailty and moderate to severe functional limitation, as well as in each Fried criterion and the SPPB test were studied. An evaluation was made of which variables conditioned changes in the probability of improving the number of frailty criteria. Quantitative variables were reported as the mean and standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables as percentages. Continuous variables exhibiting a normal data distribution were compared with the Student t-test. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used in the case of variables with a non-normal data distribution. The chi-squared test was used for the contrasting of proportions. Once the comparisons were made, the probability of improving frailty through exercise was assessed using a binary regression technique. The data were analyzed using the SPSS version 21.0 statistical package (Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was considered for p<0.05 in all cases.

ResultsPatients included in the study. Baseline characteristicsA total of 55 patients were recruited, and 44 completed the 6-month follow-up period. Of the 11 patients lost to follow-up, 10 failed to come to the scheduled visits and one died. The baseline characteristics were: mean age 77.3±5.3 years; mean duration of diabetes 15.2±10.6 years; proportion of women 72.7%; the BMI 28.4±4.3kg/m2; waist circumference 98.7±11.3cm; HbA1c 7.6±1.5%; systolic blood pressure 135.2±24.9mmHg; diastolic blood pressure 71.9±12.7mmHg; albuminuria 62.8±103.1mg/g; total cholesterol 169.6±37.9mg/dl; LDL-c 97.3±38.9mg/dl; HDL-c 47.3±13.8mg/dl; triglycerides 143.6±116.6mg/dl; smokers 7.4%; and 25-OH-vitamin D 19.9±9.2ng/ml.

The comorbidities showed the following prevalences: diabetic retinopathy 27.3%, chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate <60ml/min) 41.5%, diabetic polyneuropathy 29.1%, coronary disease 18.2%, stroke 9.1%, peripheral artery disease 12.7%, the use of antidepressants 11.1%, the use of anxiolytics together with antidepressants 13%, the use of hypnotics 25.9%.

Treatments used. Variation of metabolic variables over timeThe mean daily number of drugs per patient was 12.1±3. As regards antidiabetic drugs, metformin was used in 64.8% of the cases, sulfonylureas in 9.3%, repaglinide in 16.7%, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors in 50.2%, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in 13%, slow-acting insulin in 40.8%, fast-acting insulin in 18.5%, and mixed insulins in 9.3%. Vitamin D was taken by 40.7% of the subjects.

Significant improvements were seen at 6 months in HbA1c (final value 7±1.1%; p=0.005) and LDL-c (final value 83.3±35mg/dl; p=0.011), but not in body weight, waist circumference, blood pressure, albuminuria, other lipids or vitamin D.

Adherence to exerciseNon-adherence to the aerobic exercises occurred in 17 cases (38.6%) and to the elastic band exercises in 21 cases (47.7%).

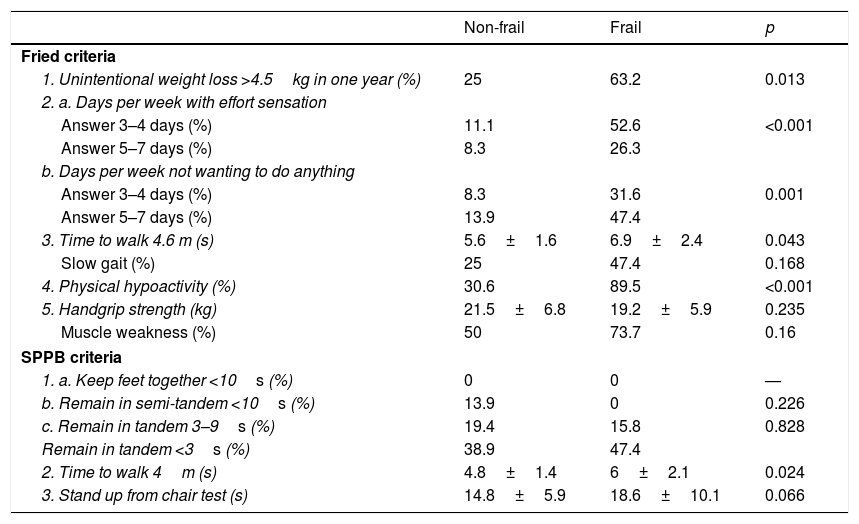

Frailty prevalence and diagnostic criteriaAccording to the Fried criteria, 34.1% of the patients were initially frail and 58.2% were pre-frail. According to the SPPB criteria, 1.8% of the patients suffered severe functional limitation, 24.4% moderate limitation, 38.2% mild limitation, and 34.5% minimal functional limitation. There were no differences in the baseline characteristics or in adherence to exercise according to the diagnosis of frailty. Table 3 shows the differences recorded in the Fried criteria and SPPB according to the initial presence of frailty. The proportion of patients with final moderate to severe limitation tended to increase (40% among the frail patients and 11.2% among the non-frail patients; p=0.073).

Differences in the Fried criteria and Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) according to baseline frailty.

| Non-frail | Frail | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fried criteria | |||

| 1. Unintentional weight loss >4.5kg in one year (%) | 25 | 63.2 | 0.013 |

| 2. a. Days per week with effort sensation | |||

| Answer 3–4 days (%) | 11.1 | 52.6 | <0.001 |

| Answer 5–7 days (%) | 8.3 | 26.3 | |

| b. Days per week not wanting to do anything | |||

| Answer 3–4 days (%) | 8.3 | 31.6 | 0.001 |

| Answer 5–7 days (%) | 13.9 | 47.4 | |

| 3. Time to walk 4.6 m (s) | 5.6±1.6 | 6.9±2.4 | 0.043 |

| Slow gait (%) | 25 | 47.4 | 0.168 |

| 4. Physical hypoactivity (%) | 30.6 | 89.5 | <0.001 |

| 5. Handgrip strength (kg) | 21.5±6.8 | 19.2±5.9 | 0.235 |

| Muscle weakness (%) | 50 | 73.7 | 0.16 |

| SPPB criteria | |||

| 1. a. Keep feet together <10s (%) | 0 | 0 | — |

| b. Remain in semi-tandem <10s (%) | 13.9 | 0 | 0.226 |

| c. Remain in tandem 3–9s (%) | 19.4 | 15.8 | 0.828 |

| Remain in tandem <3s (%) | 38.9 | 47.4 | |

| 2. Time to walk 4m (s) | 4.8±1.4 | 6±2.1 | 0.024 |

| 3. Stand up from chair test (s) | 14.8±5.9 | 18.6±10.1 | 0.066 |

Continuous variables are reported as the mean±standard deviation.

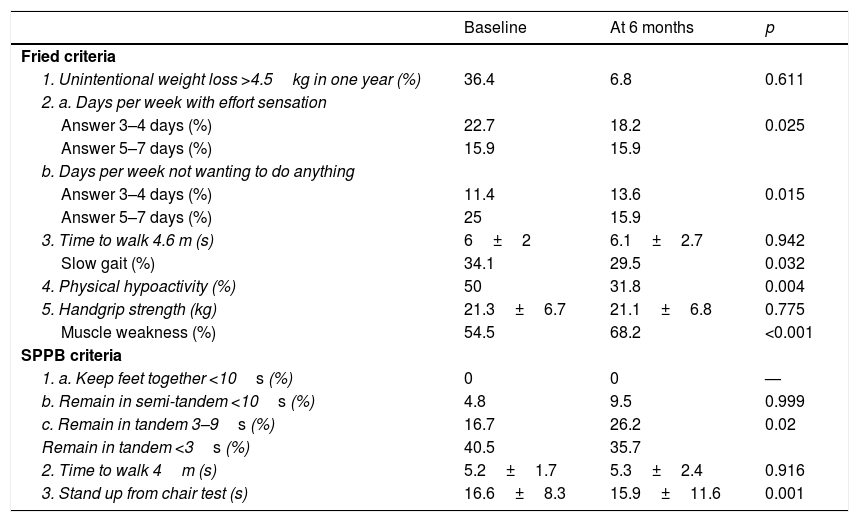

After completing the 6 months of exercise, Fried criteria improved in 47.7% of the patients, remained constant in 38.6%, and worsened in 13.6%. The prevalence of frailty decreased from 34.1% to 25% (p=0.043); 53.3% of the initially frail patients were free of frailty at the end of the study, while 13.8% of the initially non-frail elderly were found to be frail at 6 months. After 6 months, the SPPB score improved in 47.6% of the subjects, remained constant in 23.8%, and worsened in 28.6%. The percentage of patients with moderate to severe functional limitation decreased from 26.2% to 21.4% (p=0.007). Table 4 shows the variation of each Fried criterion and the SPPB over the 6-month period.

Variation in Fried criteria and the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) after 6 months of aerobic and muscle strength exercises with elastic bands.

| Baseline | At 6 months | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fried criteria | |||

| 1. Unintentional weight loss >4.5kg in one year (%) | 36.4 | 6.8 | 0.611 |

| 2. a. Days per week with effort sensation | |||

| Answer 3–4 days (%) | 22.7 | 18.2 | 0.025 |

| Answer 5–7 days (%) | 15.9 | 15.9 | |

| b. Days per week not wanting to do anything | |||

| Answer 3–4 days (%) | 11.4 | 13.6 | 0.015 |

| Answer 5–7 days (%) | 25 | 15.9 | |

| 3. Time to walk 4.6 m (s) | 6±2 | 6.1±2.7 | 0.942 |

| Slow gait (%) | 34.1 | 29.5 | 0.032 |

| 4. Physical hypoactivity (%) | 50 | 31.8 | 0.004 |

| 5. Handgrip strength (kg) | 21.3±6.7 | 21.1±6.8 | 0.775 |

| Muscle weakness (%) | 54.5 | 68.2 | <0.001 |

| SPPB criteria | |||

| 1. a. Keep feet together <10s (%) | 0 | 0 | — |

| b. Remain in semi-tandem <10s (%) | 4.8 | 9.5 | 0.999 |

| c. Remain in tandem 3–9s (%) | 16.7 | 26.2 | 0.02 |

| Remain in tandem <3s (%) | 40.5 | 35.7 | |

| 2. Time to walk 4m (s) | 5.2±1.7 | 5.3±2.4 | 0.916 |

| 3. Stand up from chair test (s) | 16.6±8.3 | 15.9±11.6 | 0.001 |

Continuous variables are reported as the mean±standard deviation.

Improvement of frailty was associated with weight gain (+0.8±2.4kg for those who improved, −1.7±2.6kg for those who did not improve; p=0.003), an increase in waist circumference (+0.8±5.5cm for those who improved, −2.1±3.4cm for those who did not improve; p=0.038), and a shortened time to walk 4.6m (−0.6±1s for those who improved, +0.6±2.2s for those who did not improve; p=0.024). Patients who improved in terms of frailty started with a lesser waist circumference (97±8.7cm for those who improved, 103.8±11.6cm for those who did not improve; p=0.033), had a lower prevalence of coronary disease (4.8% for those who improved, 34.8% for those who did not improve; p=0.036), and showed better adherence to aerobic exercise (85.7% for those who improved, 52.2% for those who did not improve; p=0.039), but not to muscle strength exercise (57.1% for those who improved, 65.2% for those who did not improve; p=0.811). No relationship was found between improvement in frailty and the baseline HbA1c levels (7.3±1% for those who improved, 7.9±1.7% for those who did not improve; p=0.162) or 25-OH-vitamin D levels (22.2±12.1ng/ml for those who improved, 18.7±7.2ng/ml for those who did not improve; p=0.382).

On assessing the improvement in frailty by binary logistic regression analysis, adherence to aerobic exercise (odds ratio [OR]=6.32; p=0.034) and the absence of coronary disease (OR=11.11; p=0.043), but not baseline waist circumference, were found to be independent predictors of frailty (OR=1.06; p=0.064).

DiscussionIn the present study of diabetic patients over 70 years of age with a Barthel score of >80 points and a GDS-FAST <3 points, the performance of 6 months of strength exercises with an elastic band three days a week and walking for 30min a day 5 days a week, was seen to result in a decrease in the prevalence of frailty according to the Fried criteria from 34.1% to 25%. The likelihood of an improvement of frailty decreased in the case of coronary disease and increased with adherence to the aerobic exercises.

A limitation of this study was the high dropout rate (20%) and significant non-adherence to the muscle strength exercises (47.7%). A lack of supervision in performing the exercises may have contributed to these percentages. Dunstan et al. emphasized the importance of such supervision in a study involving elderly diabetic patients. These authors found resistance training performed at home to be effective in maintaining the improvement in muscle strength achieved after an initial 6-month period of supervised training, though the achieved improvement in glycemic control was not maintained.20 Another limitation of our study was the choice of elastic bands as a tool to train muscle strength in these patients. Although elastic bands are easy to manage in the clinic and to transport, it is difficult to monitor the subjects’ compliance with the recommendation to mobilize 60–70% of the maximum load.21 Failure to reach such moderate to high intensity could explain why adherence to the muscle strength exercises with elastic bands failed to improve frailty, in contrast to the effect seen with the aerobic exercises. An advantage of our study was the geriatric assessment instruments used, i.e., the Fried criteria and the SPPB, which allowed for integral assessment of frailty and an approach to the latter as a dynamic disorder that can be improved, mainly through aerobic exercises, in adequately selected diabetic elderly people.

The benefits of aerobic exercise in elderly diabetic patients have been demonstrated in terms of a range of parameters. Sung et al. showed that when these patients walk 50min a day, three days a week for 6 months, physical strength increases and HbA1c and triglyceride levels decrease.22 Madden et al. randomized 36 elderly people with type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure and dyslipidemia to a supervised exercise program with exercise machines and treadmills, three days a week for three months, and found arterial stiffness to decrease in those who performed these vigorous aerobic exercises.23 In any case, the findings of our study regarding the influence of coronary disease (the absence of which increases the probability of improving frailty through exercise 11-fold), warrant consideration of this disease antecedent when prescribing a physical activity program for diabetic elderly patients.

The relationship between cardiovascular disease and frailty was analyzed in the LASA study, involving 1432 elderly patients (115 with diabetes), where heart failure was found to increase the risk of frailty 2.7-fold after 8.4 years of follow-up.24 Schopfer and Forman reported that cardiac rehabilitation may benefit elderly patients with cardiovascular disease by addressing frailty through the improvement of cardiorespiratory capacity, strength and balance.25 Unlike in our study, where the efforts focused on physical exercise, these authors conceived cardiac rehabilitation in a broader sense, as a lifestyle program addressing physical exercise, therapeutic education, dietary measures and the promotion of adherence. For the frail elderly population, the impact of lifestyle changes upon functional capacity and quality of life is currently being investigated in the context of the MID-Frail clinical trial.18

Further studies are needed to clarify the relationship between the course of frailty and waist circumference, which in our multivariate analysis tended toward statistical significance as an independent predictor of improvement in frailty on performing physical exercise. In England, Hubbard et al. measured waist circumference, the BMI and frailty in 3055 representative adults over 65 years of age, showing that the lowest prevalence of frailty was found with a BMI of 25–29.9kg/m2. Furthermore, in each BMI range, those patients with a large waist circumference (≥88cm for women, ≥102cm for men) were significantly more frail.26 Liao et al. studied these same parameters in 6320 Chinese subjects over 65 years of age and found waist circumference (≥80cm for women, ≥85cm for men) to be more closely related to the risk of frailty than the BMI.27 The joint measurement of waist circumference and frailty could provide information of interest for the care of elderly patients with type 2 diabetes and for the evaluation of the recommended treatments for these patients, the objectives of which should be to preserve functional capacity and improve quality of life.21

ConclusionsPerforming strength exercises with an elastic band for 6 months three days a week, and walking 30min a day 5 days a week, reduces the prevalence of frailty in diabetic patients over 70 years of age. The probability of improving frailty decreases in the presence of coronary disease and increases with adherence to the aerobic exercises.

AuthorshipEGD contributed to the study design, followed up on patients, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. JAR, NHF, CPG, and DGPH contributed to the study design, followed up on patients, and reviewed the manuscript.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in relation to the study contents.

Thanks are due to the drug company Almirall, which on a test basis supplied the first 10 elastic bands used in the present study.

Please cite this article as: García Díaz E, Alonso Ramírez J, Herrera Fernández N, Peinado Gallego C, Pérez Hernández DG. Efecto del ejercicio de fuerza muscular mediante bandas elásticas combinado con ejercicio aeróbico en el tratamiento de la fragilidad del paciente anciano con diabetes mellitus tipo 2. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2019;66:563–570.