Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) require education about the disease aimed at improving their knowledge and skills for its control. The objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of nutritional therapy and education using a multimedia site to improve the level of knowledge and metabolic control in patients with T2DM.

Patients and methodsAn open-label clinical trial where 161 patients with T2DM were followed up for 12 months. One hundred and one patient were randomized to the intervention group with Nutrition Therapy (NT) + NUTRILUV (multimedia site in diabetes), and 80 patients to the NT control group. Glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), glucose, cholesterol, triglyceride, and LDL and HDL cholesterol levels were measured at trial start and end. Weight, waist circumference (WC), percent fat, systolic blood pressure (SBP), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were recorded. Level of knowledge was measured using the Diabetes Knowledge Questionnaire (DKQ24).

ResultsKnowledge of diabetes improved in the group with NT + NUTRILUV as compared to the TN group (p < 0.05). HbA1c, HDL, SBP, and WC improved in the NT + NUTRILUV group (p < 0.05). In the NT group, improvements were seen in HDL cholesterol, DBP, and WC, and percent fat increased. (p < 0.05). Patients with longer times since diagnosis of diabetes had a higher risk of having HbA1c levels >7%.

ConclusionUse of a multimedia site to provide education in diabetes improves knowledge of the disease, HbA1c, and other indicators of cardiovascular risk in patients with T2DM.

El paciente con diabetes mellitus tipo 2 requiere recibir educación acerca de la enfermedad dirigida a mejorar los conocimientos y habilidades para su control. El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar la eficacia de la terapia nutricia y educación a través de un sitio multimedia, sobre el nivel de conocimientos y control metabólico en pacientes con diabetes tipo 2.

Material y métodosEnsayo clínico abierto de 12 meses de seguimiento en 161 pacientes con diabetes tipo 2. Se asignaron 101 pacientes al grupo de intervención con Terapia Nutricional (TN) +NUTRILUV (sitio multimedia), 80 pacientes al grupo control con TN. Se midió al inicio y final la Hemoglobina glucosilada (HbA1c), glucosa, colesterol, triglicéridos, colesterol LDL y HDL. Se registró el peso, circunferencia cintura (CC), porcentaje de grasa, presión arterial sistólica (PAS) y diastólica (PAD). El nivel de conocimientos se midió con el cuestionario de conocimientos en diabetes DKQ24 por sus siglas en ingles.

ResultadosLos conocimientos en diabetes mejoraron en el grupo con TN + NUTRILUV comparado con el grupo TN (p < 0.05). La HbA1c, HDL, PAD, y circunferencia de cintura mejoraron en el grupo con TN + NUTRILUV (p < 0.05). En el grupo con TN mejoró el colesterol HDL, PAD, circunferencia de cintura y se incrementó el porcentaje de grasa (p < 0.05). Presentaron mayor riesgo de una HbA1c>7% quienes tuvieron más años de diagnóstico de la diabetes.

ConclusiónEl uso de un sitio multimedia para proveer educación en diabetes, mejora los conocimientos, HbA1c, y otros indicadores de riesgo cardiovascular en pacientes con diabetes tipo 2.

It has been estimated that in 2016 there were 422 million adults with type 2 diabetes (DM2) worldwide.1 In Mexico, the 2016 National Health Survey of Medio Camino (Encuesta Nacional de Salud de Medio Camino) estimated that 9.4% of all Mexican adults had DM2 (approximately 6.4 million people), and that only 25.3% had adequate metabolic control with glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) < 7%.2

As part of the comprehensive treatment, patients with DM2 require therapeutic education (TE) about the disease, which should be aimed at improving knowledge and skills and increasing the motivation for diabetes care, and promoting the adoption of a healthy lifestyle.3 In recent years, both information technology (IT) and health communication have been adopted to provide TE in different disease conditions, including diabetes.4 The optimization of nutritional therapy has been shown to improve HbA1c and other cardiovascular risk indicators in patients with DM2.5 The use of IT has been related to improved knowledge of the disease, eating habits and diabetes care.6,7 In diabetic patients, some studies on the use of IT have reported improvements in HbA1c, lipid profile and body weight, as well as in disease self-care.8,9

With regard to increasing knowledge of diabetes by the use of IT, improvement has been reported in insulin utilization for disease control as compared to standard medical therapy.10 In diabetic patients with a low educational level, the use of IT may facilitate greater understanding and learning regarding disease control.11 Likewise, multimedia tools have been used to promote the incorporation of physical exercise into disease care.12 Although IT has been used in other countries to improve knowledge, lifestyle and self-care in diabetic patients, only limited information is available on its usefulness in regard to its application to patients and healthcare professionals in Mexico. It should be noted, however, that the outcomes of IT use remain controversial, particularly in terms of metabolic control and its relationship to improved knowledge of the disease.13

The present study was carried out to assess the impact of nutritional therapy and education through a multimedia site upon the level of knowledge and metabolic control in Mexican patients with DM2.

Material and methodsStudy design and populationAn open-label 12-month follow-up trial was conducted in patients with DM2 attending three primary care centers of the Mexican Social Security Institute (Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social) in Mexico City. The study was carried out from February 2017 to August 2018. The investigation was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Mexican Social Security Institute. All the patients signed the informed consent form for participation in the study, following clarification of any possible concerns. The sample size was calculated to detect a difference of 0.6% in HbA1c between the two groups, with an error α of 0.05 and 95% capacity to detect the difference (1-β = 0.95). A sample size of 51 participants per group was seen to be required. Anticipating a 20% loss to follow-up, at least 61 patients were considered for inclusion in each group.

Participant eligibility criteriaWe included patients with less than 20 years from the time of diagnosis of DM2, an age of ≤ 65 years, the the ability to read and write in Spanish, and with HbA1c > 6.5% and ≤ 13%. Patients with a prior diagnosis of advanced diabetic retinopathy or blindness, severe diabetic neuropathy or diabetic foot, as well as those with chronic renal failure subjected to renal replacement therapy were excluded. Patients were excluded due to the need for specific medical and nutritional treatment that would affect the outcome variables.

Sociodemographic and clinical parametersSociodemographic, clinical and comorbidity data were collected through questioning and from the clinical examination of the patient performed by the investigating physician. Blood pressure was measured twice with a mercury sphygmomanometer, with a 5-minute interval between the two measurements, and after the patient had remained seated for more than 5 minutes. The recorded blood pressure value was the average of these two measurements.

Biochemical parametersThe HbA1c concentration was measured in venous blood following a 12-h fasting period using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Glucose, serum creatinine and lipid profile (total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL- and LDL-cholesterol) were measured using the automated photometry technique. The biochemical determinations were made using a Roche Cobas 800 c701 analyzer.

Body composition and anthropometric parametersThe anthropometric parameters were recorded by two previously calibrated nutritionists using the method proposed by Habitch and in accordance with the specifications recommended by Lohman et al.14,15 Body weight and height were obtained using a model TBF-215 TANITA scale™, and percentage body fat was documented using lower segment bioelectrical impedance analysis. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated from weight and height. Waist circumference was measured from the midpoint between the last rib and the upper border of the iliac crest on the right side. The value was recorded three times, and the mean of the second and third measurements was used for analysis.

Assessment of knowledge about diabetesUse was made of the Diabetes Knowledge Questionnaire (DKQ24), validated for determining the level of knowledge of the disease in diabetic patients. This tool comprises 24 questions referring to the etiology, signs and symptoms, diagnosis, pharmacological treatment and lifestyle management, and complications of DM2. Each of the 24 questions has three possible answers: "yes", "no" and "I don't know". The 24 questions address the following areas for scoring the questionnaire: basic knowledge of the disease (10 items), glycemic control (7 items) and the prevention of complications (7 items).16 The level of knowledge as assessed by the DKQ24 is rated as either sufficient (greater than or equal to 17 correct answers; ≥ 70% of the total) or insufficient (≤ 16 correct answers or less).

Patient assignmentThe patients were assigned on their inclusion in the study to either the control group to receive nutritional therapy (NT) or to the intervention group, which received NT plus diabetes education through the Nutriluv® Multimedia guide in Diabetes and Nutrition. The intervention was open-labeled for the investigators and the participants.

Nutritional therapy groupThe control group received personalized nutritional therapy by a certified nutritionist according to gender, age, weight and current comorbidity (dyslipidemia, obesity, arterial hypertension and kidney disease). The patients were questioned regarding their food preferences, portion sizes, tastes and timetable. To provide nutritional therapy, representations of meals were used to increase understanding of the educational nutritional intervention.

The nutritional and caloric recommendations were established according to the Official Mexican Standard for diabetes and the American Diabetes Association,17,18 with a distribution comprising carbohydrates 50–55%, proteins 15–20% and fats 25–30% (with less than 10% saturated fats). The fiber content was established as 14 g/1000 kcal and the sodium content as ≤ 2000 mg/day in the daily diet. The Mexican Equivalent Food System was used to define the diet, and the different food groups (cereals, fruits, vegetables, meats, milk, legumes and fats) were explained. The patients received a brochure with the indicated diet, five example menus according to the assigned calories, and a section for recording indicators in the clinic, as well as recommendations for a healthy diet and physical exercise.

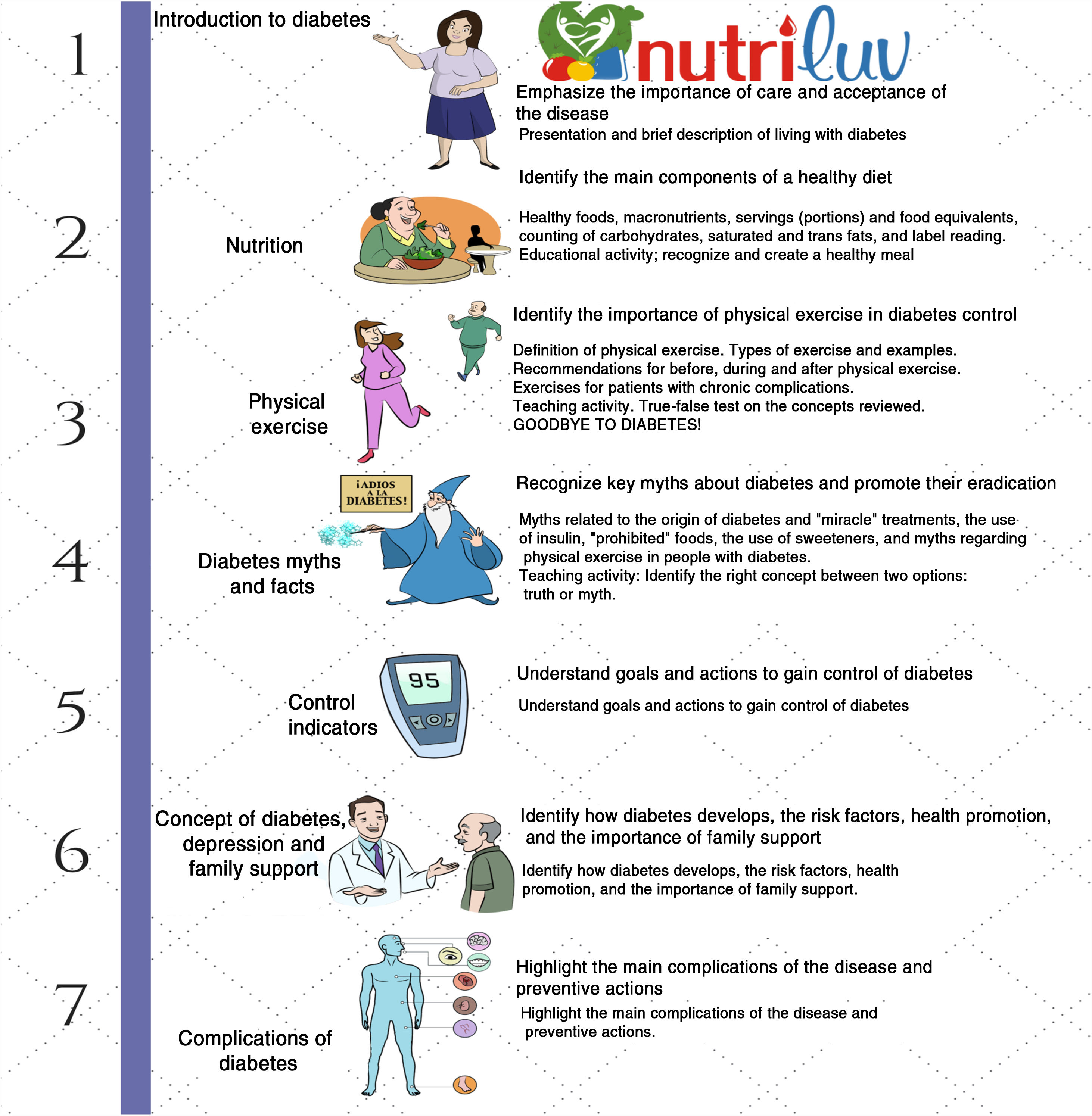

Nutritional therapy and diabetes education groupThe Nutriluv® Multimedia guide in Diabetes and Nutrition educational program is available at http://nutriluv.mx. The objectives of the Nutriluv® site are described in Fig. 1. This educational tool was designed by a multidisciplinary group consisting of an epidemiologist, two physicians, a psychologist, and two certified dieticians with clinical experience in diabetes. Its characteristics were described in a previous report.19 The patients had access to the different educational modules for approximately 15–20 min using text and audio, with reinforcement messages providing guidance, and educational activities at the end of each module to consolidate their knowledge. Testimonial videos from patients who lived with some complication of diabetes were also included at the end, in order to emphasize peer education.

The patients in the experimental group visited the educational site each month during the first 6 months. On each appointment they addressed a different module in an area designed exclusively for this purpose, before receiving nutritional therapy. The patients were subsequently appointed visits after 8, 10 and 12 months. The control group attended the same visits to receive personalized nutritional therapy. In both groups, the eating plan was reinforced at each visit, and capillary blood glucose, weight, waist circumference and blood pressure were measured. In the experimental group, in addition to nutritional therapy, educational modules on the multimedia platform and personalized reinforcement of TE by the nutrition professional were reviewed. At the start and after 12 months of follow-up, the biochemical indicators were again measured in a blood sample, together with the anthropometric and body composition parameters. Those who completed at least 7 follow-up visits during the study (80% of the visits) were considered for the study analysis.

Data analysisDescriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation [SD], median and interquartile range [IQR]) were used to describe the baseline characteristics of the study population. The χ2 test was used to assess the baseline characteristics of the patients, as well as the change in knowledge about diabetes.

A paired Student t-test was used to compare the differences in biochemical, clinical and anthropometric parameters within groups in the course of follow-up. A multivariate logistic regression model was used to assess the effect upon the risk of having HbA1c ≥ 7%.

Statistical significance was considered for p < 0.05 in all cases. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 25, was used throughout.

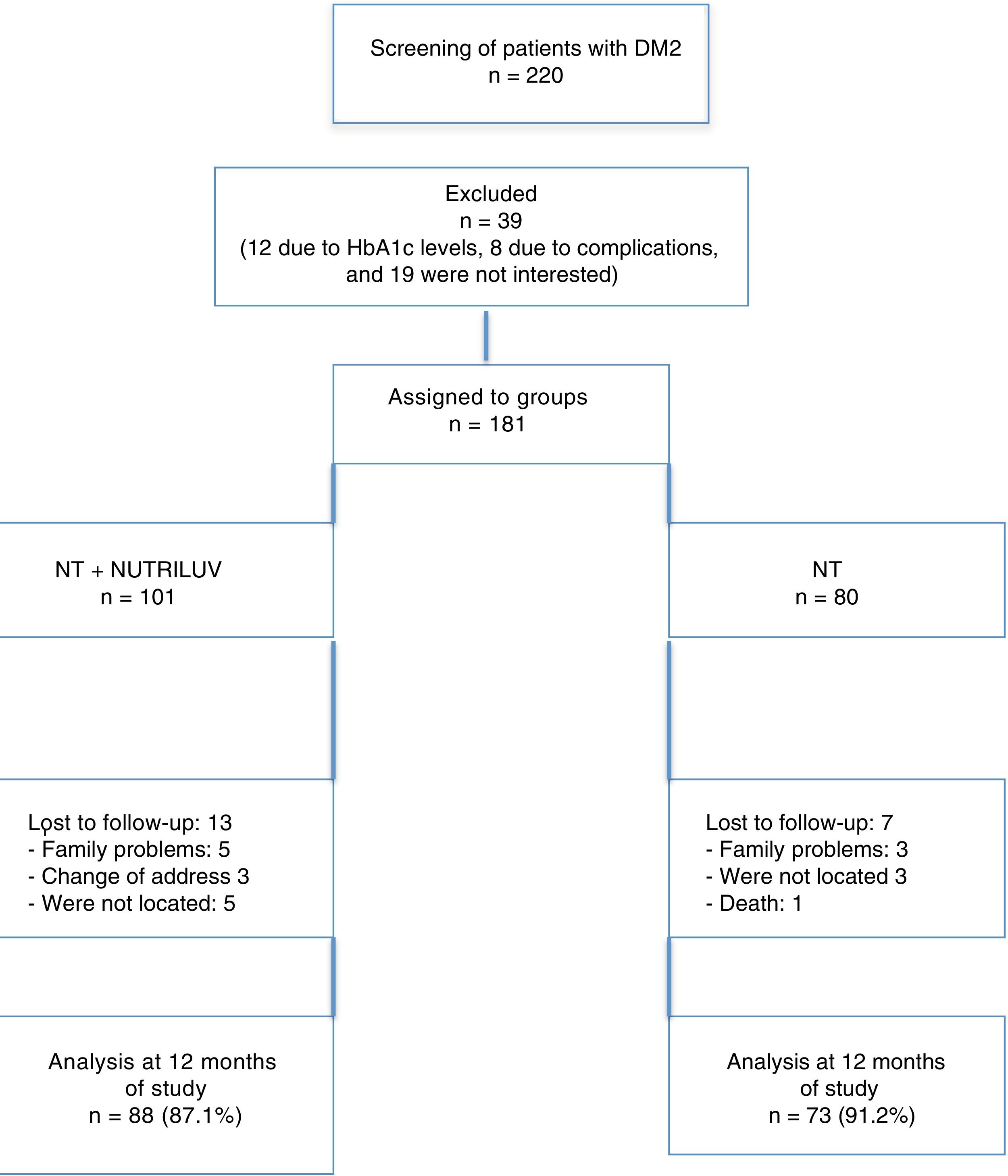

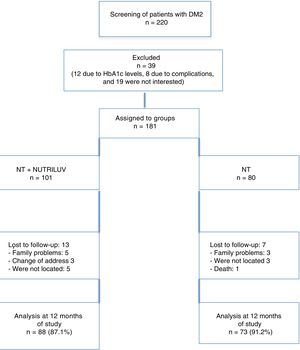

ResultsA total of 220 patients were included in the screening phase. Of these, 39 were excluded, since 12 of them had out-of-range HbA1c levels, 8 had disease complications, and 19 patients were not interested in participating in the follow-up. A total of 101 patients were assigned to the NT + Nutriluv group and 80 patients to the NT group. Twenty-six patients in the NT + Nutriluv group (16.9%) and 14 patients in the NT group (7.8%) were lost to follow-up. In turn, 161 patients completed the follow-up stage: 88 in the NT + Nutriluv group and 73 in the NT group. These data are shown in Fig. 2.

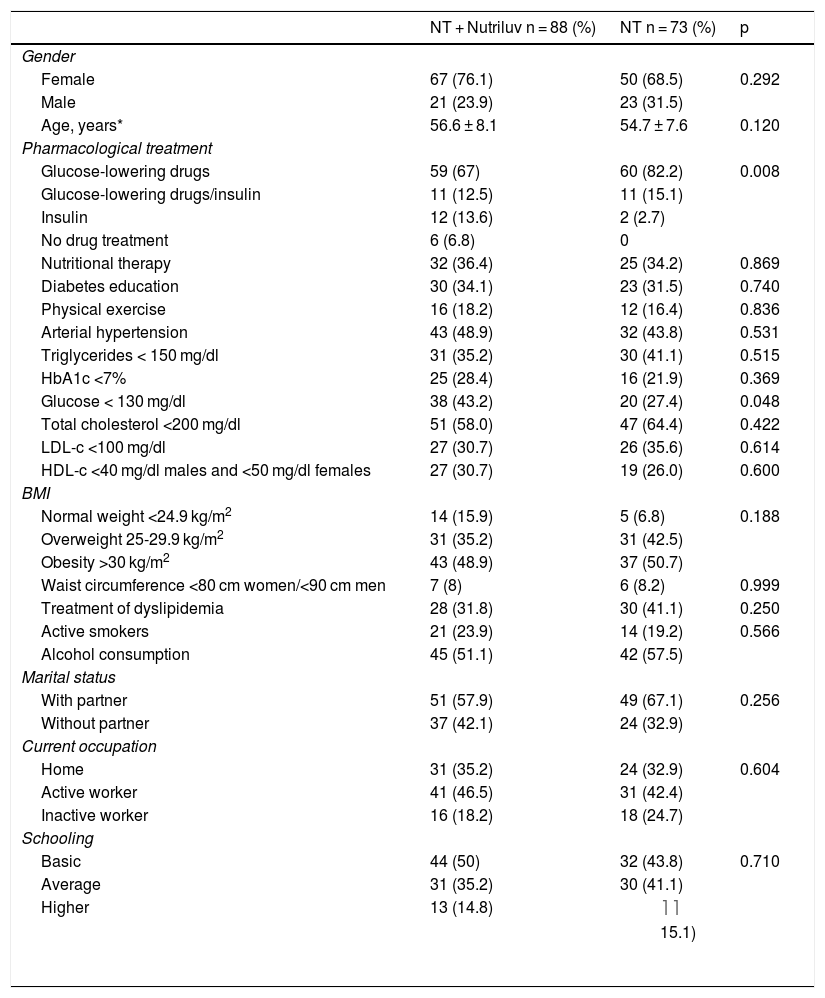

The mean age was 56.6 years in the NT + Nutriluv group and 54.7 years in the NT group. The duration of the disease was 7.9 and 6.7 years, respectively. Blood glucose-lowering drugs were the most commonly used pharmacological treatment in both groups. Arterial hypertension was present in 48.9% of the NT + Nutriluv group and in 43.8% of the NT group. With regard to the lipid profile, both groups showed alterations mainly in LDL-cholesterol and triglycerides. Basic primary and secondary education predominated in both groups. These data are reported in Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics and comorbidities of both groups of patients at baseline.

| NT + Nutriluv n = 88 (%) | NT n = 73 (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 67 (76.1) | 50 (68.5) | 0.292 |

| Male | 21 (23.9) | 23 (31.5) | |

| Age, years* | 56.6 ± 8.1 | 54.7 ± 7.6 | 0.120 |

| Pharmacological treatment | |||

| Glucose-lowering drugs | 59 (67) | 60 (82.2) | 0.008 |

| Glucose-lowering drugs/insulin | 11 (12.5) | 11 (15.1) | |

| Insulin | 12 (13.6) | 2 (2.7) | |

| No drug treatment | 6 (6.8) | 0 | |

| Nutritional therapy | 32 (36.4) | 25 (34.2) | 0.869 |

| Diabetes education | 30 (34.1) | 23 (31.5) | 0.740 |

| Physical exercise | 16 (18.2) | 12 (16.4) | 0.836 |

| Arterial hypertension | 43 (48.9) | 32 (43.8) | 0.531 |

| Triglycerides < 150 mg/dl | 31 (35.2) | 30 (41.1) | 0.515 |

| HbA1c <7% | 25 (28.4) | 16 (21.9) | 0.369 |

| Glucose < 130 mg/dl | 38 (43.2) | 20 (27.4) | 0.048 |

| Total cholesterol <200 mg/dl | 51 (58.0) | 47 (64.4) | 0.422 |

| LDL-c <100 mg/dl | 27 (30.7) | 26 (35.6) | 0.614 |

| HDL-c <40 mg/dl males and <50 mg/dl females | 27 (30.7) | 19 (26.0) | 0.600 |

| BMI | |||

| Normal weight <24.9 kg/m2 | 14 (15.9) | 5 (6.8) | 0.188 |

| Overweight 25-29.9 kg/m2 | 31 (35.2) | 31 (42.5) | |

| Obesity >30 kg/m2 | 43 (48.9) | 37 (50.7) | |

| Waist circumference <80 cm women/<90 cm men | 7 (8) | 6 (8.2) | 0.999 |

| Treatment of dyslipidemia | 28 (31.8) | 30 (41.1) | 0.250 |

| Active smokers | 21 (23.9) | 14 (19.2) | 0.566 |

| Alcohol consumption | 45 (51.1) | 42 (57.5) | |

| Marital status | |||

| With partner | 51 (57.9) | 49 (67.1) | 0.256 |

| Without partner | 37 (42.1) | 24 (32.9) | |

| Current occupation | |||

| Home | 31 (35.2) | 24 (32.9) | 0.604 |

| Active worker | 41 (46.5) | 31 (42.4) | |

| Inactive worker | 16 (18.2) | 18 (24.7) | |

| Schooling | |||

| Basic | 44 (50) | 32 (43.8) | 0.710 |

| Average | 31 (35.2) | 30 (41.1) | |

| Higher | 13 (14.8) |

| |

*Mean and standard deviation.

Fig. 3 shows that 23.3% of the patients in the NT group had sufficient knowledge, versus 35.2% in the NT + Nutriluv group (p = 0.069). At the end of the intervention, these figures increased to 49.3% and 67.0%, respectively (p = 0.017).

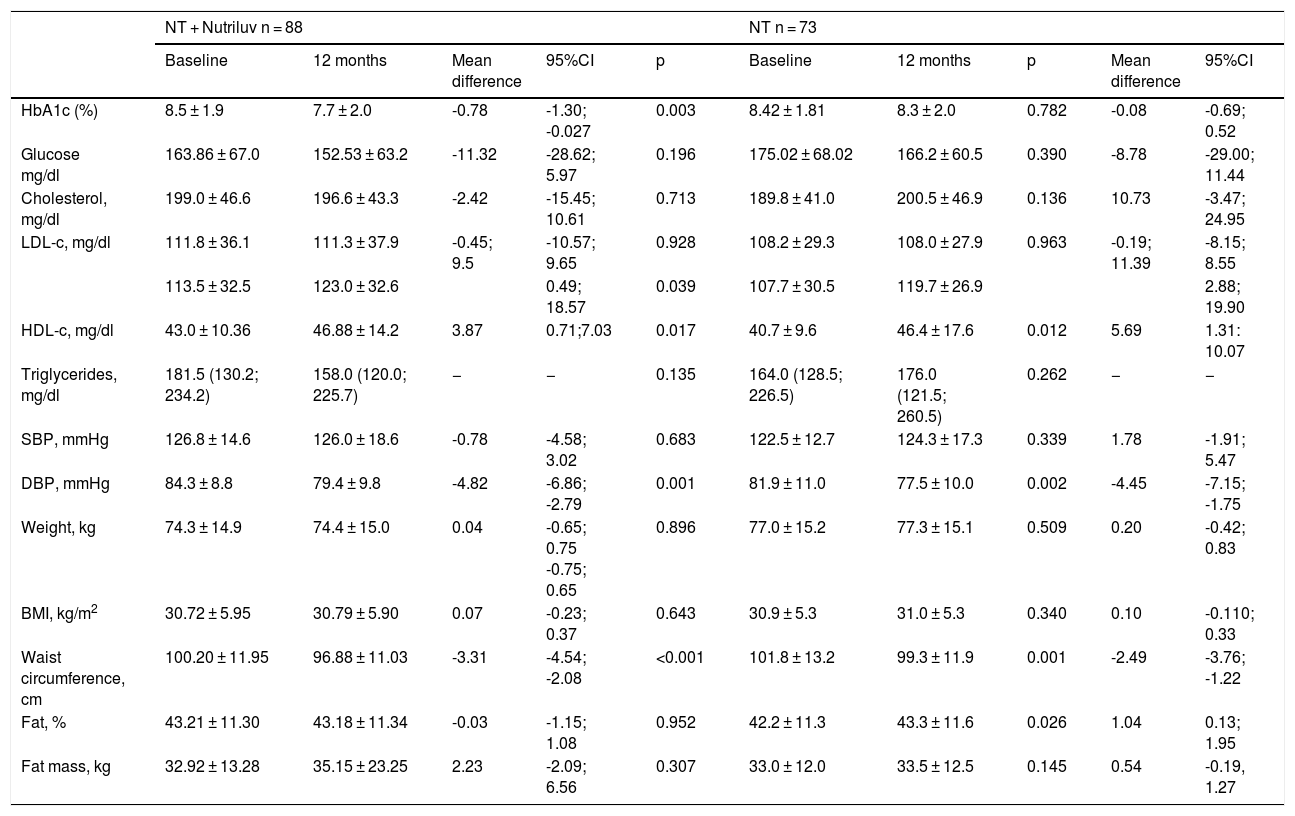

Table 2 shows the biochemical, clinical, anthropometric and body composition values during follow-up. The HbA1c values had improved significantly at the end of the intervention in the NT + Nutriluv group (p = 0.003). There had been a significant increase in HDL-cholesterol (p = 0.017) and a significant decrease in mean diastolic blood pressure (p = 0.001) and waist circumference at the end of the intervention (p = 0.001). In the NT group, HDL-cholesterol had significantly increased (p = 0.012), as had diastolic blood pressure (p = 0.002), waist circumference (p = 0.026) and percentage body fat (p = 0.026).

Modification of the biochemical, clinical and anthropometric indicators in both study groups.

| NT + Nutriluv n = 88 | NT n = 73 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 12 months | Mean difference | 95%CI | p | Baseline | 12 months | p | Mean difference | 95%CI | |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.5 ± 1.9 | 7.7 ± 2.0 | -0.78 | -1.30; -0.027 | 0.003 | 8.42 ± 1.81 | 8.3 ± 2.0 | 0.782 | -0.08 | -0.69; 0.52 |

| Glucose mg/dl | 163.86 ± 67.0 | 152.53 ± 63.2 | -11.32 | -28.62; 5.97 | 0.196 | 175.02 ± 68.02 | 166.2 ± 60.5 | 0.390 | -8.78 | -29.00; 11.44 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dl | 199.0 ± 46.6 | 196.6 ± 43.3 | -2.42 | -15.45; 10.61 | 0.713 | 189.8 ± 41.0 | 200.5 ± 46.9 | 0.136 | 10.73 | -3.47; 24.95 |

| LDL-c, mg/dl | 111.8 ± 36.1 | 111.3 ± 37.9 | -0.45; 9.5 | -10.57; 9.65 | 0.928 | 108.2 ± 29.3 | 108.0 ± 27.9 | 0.963 | -0.19; 11.39 | -8.15; 8.55 |

| 113.5 ± 32.5 | 123.0 ± 32.6 | 0.49; 18.57 | 0.039 | 107.7 ± 30.5 | 119.7 ± 26.9 | 2.88; 19.90 | ||||

| HDL-c, mg/dl | 43.0 ± 10.36 | 46.88 ± 14.2 | 3.87 | 0.71;7.03 | 0.017 | 40.7 ± 9.6 | 46.4 ± 17.6 | 0.012 | 5.69 | 1.31: 10.07 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 181.5 (130.2; 234.2) | 158.0 (120.0; 225.7) | − | − | 0.135 | 164.0 (128.5; 226.5) | 176.0 (121.5; 260.5) | 0.262 | − | − |

| SBP, mmHg | 126.8 ± 14.6 | 126.0 ± 18.6 | -0.78 | -4.58; 3.02 | 0.683 | 122.5 ± 12.7 | 124.3 ± 17.3 | 0.339 | 1.78 | -1.91; 5.47 |

| DBP, mmHg | 84.3 ± 8.8 | 79.4 ± 9.8 | -4.82 | -6.86; -2.79 | 0.001 | 81.9 ± 11.0 | 77.5 ± 10.0 | 0.002 | -4.45 | -7.15; -1.75 |

| Weight, kg | 74.3 ± 14.9 | 74.4 ± 15.0 | 0.04 | -0.65; 0.75 -0.75; 0.65 | 0.896 | 77.0 ± 15.2 | 77.3 ± 15.1 | 0.509 | 0.20 | -0.42; 0.83 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30.72 ± 5.95 | 30.79 ± 5.90 | 0.07 | -0.23; 0.37 | 0.643 | 30.9 ± 5.3 | 31.0 ± 5.3 | 0.340 | 0.10 | -0.110; 0.33 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 100.20 ± 11.95 | 96.88 ± 11.03 | -3.31 | -4.54; -2.08 | <0.001 | 101.8 ± 13.2 | 99.3 ± 11.9 | 0.001 | -2.49 | -3.76; -1.22 |

| Fat, % | 43.21 ± 11.30 | 43.18 ± 11.34 | -0.03 | -1.15; 1.08 | 0.952 | 42.2 ± 11.3 | 43.3 ± 11.6 | 0.026 | 1.04 | 0.13; 1.95 |

| Fat mass, kg | 32.92 ± 13.28 | 35.15 ± 23.25 | 2.23 | -2.09; 6.56 | 0.307 | 33.0 ± 12.0 | 33.5 ± 12.5 | 0.145 | 0.54 | -0.19, 1.27 |

DBP: diastolic blood pressure; SBP: systolic blood pressure; NT: nutritional therapy; NT + Nutriluv: nutritional therapy plus diabetes education with the multimedia tool.

Student t-test for paired samples.

*Wilcoxon test.

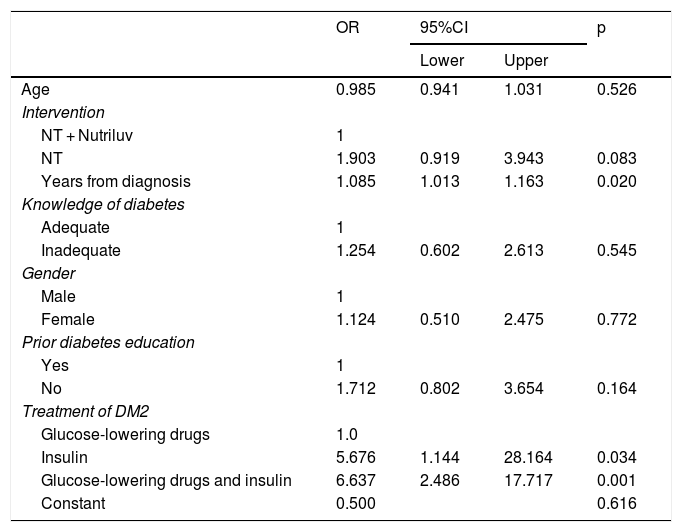

Table 3 shows the data corresponding to the logistic regression analysis, with lack of metabolic control (HbA1c >7%) as the outcome variable. The group with NT only, the patients with the longest time from diagnosis, and those treated with glucose-lowering drugs and insulin were seen to have the highest risk of HbA1c > 7%.

Multivariate logistic regression model for identifying the risk of inadequate HbA1c control at 12 months (≥7%).

| OR | 95%CI | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Age | 0.985 | 0.941 | 1.031 | 0.526 |

| Intervention | ||||

| NT + Nutriluv | 1 | |||

| NT | 1.903 | 0.919 | 3.943 | 0.083 |

| Years from diagnosis | 1.085 | 1.013 | 1.163 | 0.020 |

| Knowledge of diabetes | ||||

| Adequate | 1 | |||

| Inadequate | 1.254 | 0.602 | 2.613 | 0.545 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1 | |||

| Female | 1.124 | 0.510 | 2.475 | 0.772 |

| Prior diabetes education | ||||

| Yes | 1 | |||

| No | 1.712 | 0.802 | 3.654 | 0.164 |

| Treatment of DM2 | ||||

| Glucose-lowering drugs | 1.0 | |||

| Insulin | 5.676 | 1.144 | 28.164 | 0.034 |

| Glucose-lowering drugs and insulin | 6.637 | 2.486 | 17.717 | 0.001 |

| Constant | 0.500 | 0.616 | ||

DM2: type 2 diabetes mellitus; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio for prevalence; NT: nutritional therapy; NT + Nutriluv: nutritional therapy plus diabetes education with the multimedia tool.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a health problem due to the prevalence, high costs and impact of its complications upon patient quality of life. In this situation, accessible cost-effective interventions offering better education for diabetic patients, by providing an adequate level of knowledge of the disease and the means of improving self-care, are essential.20,21

The results of this study show therapeutic education in diabetic patients using IT in combination with nutritional therapy to improve knowledge of the disease. At the end of the study there was a greater proportion of patients with sufficient knowledge in the NT + Nutriluv group. These findings show that the use of IT in patients motivates and promotes self-care, and results in a greater level of knowledge of the disease. It has been found that IT makes available tools that effectively complement the management provided by the physician.22

The NT + Nutriluv strategy had significantly influenced metabolic control at 12 months of follow-up. The relationship between improved knowledge and its effect in terms of lowered HbA1c concentration has been reported elsewhere.23 In the present study, the experimental group showed significant improvement both in HbA1c and in knowledge at 12 months of follow-up. Other studies report data that are consistent with our own findings, with similar improvements.24 Accordingly, improved metabolic control is the result of understanding the importance of adherence to the lifestyle and drug treatment indications.

The use of IT promotes behavioral change and is a low-cost and easily accessible strategy. Ideally, the tools should be implemented by clinical professionals and adjusted according to the educational level and the social and economic situation of the patients. Such strategies may be useful as a complement to the treatment provided by physicians.25 Even though improvements in HbA1c and knowledge were identified, no significant association was found between better knowledge and improved HbA1c concentration. It is important to continue promoting positive changes in behavior related to the disease, for although patients could have knowledge about diabetes care, this does not necessarily imply behavioral changes to modify their lifestyle or adherence to drug treatment.

A similar strategy has recently been described using a mobile phone application to provide diabetes education, in which the authors reported no significant differences in glycemic control, quality of life or self-care. These results possibly may be explained by the brief duration of the intervention (only 3 months) and by the low use of the application (less than 50% of the participants used it).26

Patients in both study groups improved their HDL-cholesterol levels. Other studies have revealed the antiatherogenic effects of increased HDL-cholesterol levels, since they lower cardiovascular risk in patients with DM2.27

It is important to mention that the control group received personalized nutritional therapy, and that improvements in the metabolic control indicators were therefore expected, as previously described.

Visceral fat has been reported as increasing the flow of free fatty acids towards the liver, resulting in higher triglyceride levels, the consumption of HDL-cholesterol and a greater proportion of LDL-cholesterol, so promoting atherosclerosis and therefore raising cardiovascular risk.28

In this study we recorded a decrease in waist circumference. In this regard, it has been documented that increased visceral and subcutaneous fat is related to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.29 An indicator that was affected in the control group was percentage body fat, which increased during follow-up. It is important to emphasize the need for physical activity in the diabetic population, because only 9% performed exercise (defined as at least 150 minutes a week of moderate physical activity).

In turn, arterial hypertension is often associated with diabetes, and increases the risk of macro- and microvascular complications of the disease. At the end of the intervention, diastolic blood pressure levels decreased significantly in both groups, this being associated with a decrease in cardiovascular risk.30

The limitations of our study include a predominance of women. In this regard, we believe that health policies should be established aimed at promoting the greater involvement of males in preventive care. Another limitation is the fact that the proportion of patients with glucose control and of those who used glucose-lowering drugs and insulin differed between the two groups at the start of the study. However, we believe that the usefulness of HbA1c as outcome variable and the demonstration of the effect of drug treatment in the multivariate analysis show that an increased lack of metabolic control leads to the prescription of insulin use by the treating physician. It is advisable for future studies to assess the quality of exposure to IT outside the clinical care setting, since in this study it formed a part of nutritional therapy.

The strengths of our study include adequate systematization and the use of standardized procedures for determining metabolic markers and anthropometric measurements, as well as for the definition of the content and design of the digital tool, addressed by a multidisciplinary healthcare team.

ConclusionsThe use of a multimedia site improves knowledge concerning the disease and metabolic control in patients with DM2. Low-cost and easily accessible strategies, such as the use of IT, should continue to be promoted, aimed not only at improving knowledge, but also at achieving changes in lifestyle and care in general, with a view to preventing or delaying complications.

Authorship/collaboratorsNelsy Reséndiz participated in data collection and the educational intervention. Abril Muñoz contributed to data analysis and the review of the manuscript. Grecia Mendoza participated in the educational intervention and in data collection. Diego Zendejas participated in the educational intervention and in data collection. Patricia Medina participated in data analysis and the development of the manuscript. Lubia Velázquez participated in the conception of the study, data analysis and the development of the manuscript. All the authors have approved the final version of the manuscript and the criteria for authorship.

Financial supportNational Council of Science and Technology (Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología [CONACYT]) with registration number: SALUD-2012-1-181015.

Conflicts of interestNone.

Please cite this article as: Reséndiz Lara T, Muñoz Torres AV, Mendoza Salmerón G, Zendejas Vela DD, Medina Bravo P, Roy García I, et al. La educación con una plataforma multimedia en web mejora los conocimientos y la HbA1c de pacientes mexicanos con diabetes tipo 2. Ensayo clínico abierto. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2020;67:530–539.