The theory of fetal programming suggests that low birth weight (LBW) predisposes to greater food intake and increases the chance of overweight and obesity, which are in turn associated to conditions such as metabolic syndrome (MS) and acanthosis nigricans. The study objective was to ascertain whether an association exists between MS, LBW, intake of high-calorie diets, and acanthosis nigricans in children and adolescents with overweight or obesity.

Material and methodsA case-control was conducted on 100 children who attended the overweight and obesity outpatient clinic of the OPD Hospital Civil de Guadalajara “Fray Antonio Alcalde”. Subjects were stratified in groups with and without MS based on the criteria of the International Diabetes Federation for children aged less than 16 years. Data on LBW, intake of high-calorie diets for 24-h dietary recalls (average 2 days a week), and acanthosis nigricans (Simone criteria) were obtained by questioning the parents. Frequencies and logistic regression were calculated using SPSS version 22.

ResultsThe results show that 82% of children and adolescents were obese and 18% overweight, and 73% had MS. MS was associated to LBW (OR: 4.83 [95% CI: 1.9–12.47]), high-calorie diets (OR: 136.8 [95% CI: 7.7–2434]), and acanthosis nigricans (OR: 1872 [95% CI: 112.9–31028]).

ConclusionsIn children and adolescents with overweight and obesity, LBW, high-calorie diets, and acanthosis nigricans are associated to a higher probability of MS.

La teoría de la programación fetal sostiene que el bajo peso al nacimiento (BPN) predispone a mayor ingesta alimentaria e incrementa las probabilidades de sobrepeso y obesidad, y estas a su vez de alteraciones como síndrome metabólico (SM) y acantosis nigricans. Nuestro objetivo fue estudiar la existencia de asociación entre el SM, el BPN, el consumo de dieta hipercalórica y la acantosis nigricans, en escolares y adolescentes con sobrepeso y obesidad.

Material y métodosSe realizó un estudio de casos y control en 100 menores que acudían a la consulta de sobrepeso y obesidad del OPD Hospital Civil de Guadalajara, «Fray Antonio Alcalde»; se categorizaron con y sin SM con los criterios de la Federación Internacional de Diabetes para menores de 16 años. Se obtuvo por interrogatorio a los padres y menores, el BPN, el consumo de dietas hipercalóricas (promedio de 2 días/semana del recordatorio de 24h) y la acantosis nigricans (criterios de Simone). Las frecuencias y la regresión logística se calcularon con SPSS versión 22.

ResultadosLos resultados muestran que el 82% de los menores presentaron obesidad, el 18% sobrepeso y el 73% SM. El SM se asoció con BPN (OR: 4,83 [IC 95%: 1,9-12,47]), dieta hipercalórica (OR: 136,8 [IC 95%: 7,7-2434]) y acantosis nigricans (OR: 1872 [IC 95%: 112,9-31028]).

ConclusionesEn escolares y adolescentes con sobrepeso y obesidad se encontró que el BPN, la dieta hipercalórica y la acantosis nigricans representan mayor probabilidad de SM.

Low birth weight (LBW) is a determinant factor for health in adult life which, when associated to high-calorie diets, promotes accumulation of adipose tissue in the abdominal region and obesity. This leads to development of metabolic syndrome (MS), diabetes mellitus, and insulin resistance (IR).1

The implications of LBW are supported by the theory of “fetal programming”, that relates malnutrition in critical periods of development, such as in intrauterine life of infants with LBW, to permanent changes in metabolism and body structure.2

These changes potentially increase susceptibility to obesity and cardiovascular and metabolic diseases in adulthood, and are more severe if calorie consumption in infancy is higher than the recommended daily intake (high-calorie diet).2

A sign of IR is acanthosis nigricans (AN), whose pathophysiology is still unknown. It is clinically characterized by hyperpigmented, verrucous skin plaques with hyperkeratosis.3

The most commonly accepted theory to explain development of AN is that presence of hyperinsulinism due to IR activates insulin-like growth factor-1, which stimulates keratinocytes and skin fibroblasts, thus leading to AN.3

In Mexico, high food intake has promoted excess weight, which is a national public health problem. The 2012 National Health Survey showed that 19.8% of boys aged 10–15 years were overweight and 18.1% were obese; in girls, the corresponding rates were 29.6% and 14.8% respectively.4 This, combined with presence of LBW, may promote development of MS.

Our objective was to ascertain whether an association exists between MS, LBW, a high-calorie diet, and AN in children and adolescents with overweight and obesity.

Patients and methodsThis was a case-control study conducted from July 2013 to June 2014 on 100 children aged 10–15 years, 50 boys and 50 girls, who attended the overweight and obesity group of the pediatric nutrition clinic of the OPD Antiguo Hospital Civil de Guadalajara, “Fray Antonio Alcalde”.

The project was approved by the Committee of Bioethics and Research of that institution in accordance to the guidelines of the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki, and supported by grant no. 06-425-2009 of the Consejo Estatal de Ciencia y Tecnología from the State of Jalisco (COECYTJal).

After explaining the study to both parents and guardians, as well as minors, voluntary and confidential participation was requested and written informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians. Subjects who met the criteria and attended the obesity clinic were invited to participate, and all of them agreed to take part.

The population was categorized into two groups based on educational level: children aged 10–12 years in primary education (40) and adolescents aged 13–15 years in secondary education (60).

InstrumentsA clinical history, a SALTER digital scale, a DYNA TOP stadiometer, a flexible measuring tape of fiber, and an Omron digital sphygmomanometer were used.

ProceduresMeasurements were taken at the outpatient clinics of the hospital, and subjects were assessed in the presence of their parents or guardians.

A clinical history was recorded by directly questioning mothers or guardians about general data of the population and birth weight of the child. According to the WHO, LBW was defined as less than 2500g and a gestational age ranging from 37 and 42 weeks.5

According to the classification of the overweight and obesity department of the hospital, minors were categorized as those in primary education (aged 10–12 years) and those in secondary education (aged 13–15 years).

The physical examination was done with light, comfortable clothes and no shoes. Duplicate anthropometric measurements were performed following the recommendations of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Study6 and the WHO.7 Weight, height, and waist circumference (WC) were measured.8

According to WHO criteria, overweight was defined as a BMI value ≥85th percentile, and obesity as a BMI value ≥95th percentile.6,7

The criteria of the International Diabetes Federation for subjects younger than 16 years were used to identify MS. These include abdominal obesity (AO) plus two diagnostic criteria including BP and biochemical tests of triglycerides, HDL, and glucose.9

Triglycerides, HDL, and glucose were tested after fasting for 12h. Children were drawn peripheral blood for enzymatic-spectrophotometric quantification at the central laboratory of the hospital. Normal values were as follows: glucose <100mg/dL, HDL >40mg/dL, triglycerides <150mg/dL, systolic BP <130mmHg, and diastolic BP <85mmHg.9

After standardization with staff certified in anthropometric measurements, WC was measured with the subject standing, with arms in abduction. The right and left iliac crests were located, and both points were surrounded with the metallic measuring tape horizontally at umbilical level. Subjects were asked to inhale and exhale air for doing the measurement.9

AO was defined as WC ≥90th percentile in the Fernández et al. tables8; BP was assessed base on the criteria of the Bogalusa Heart Study.10

Simone et al. criteria11 were used for clinical diagnosis of AN. These consider the areas of the neck, armpits, elbows, knees, palms and soles, and establish the following grades of AN based on its presence in each affected site: grade 1: Imperceptible for a person with no training; grade 2: Visible but does not attract attention; grade 3: Very visible; and grade 4: Attracts attention.

Calorie consumption in diet was estimated through the 24-h recall, with the mean of two days of the week (a week day and Sunday). The 24-h recall included meal times, categorizing all food taken during the day as breakfast, morning snack, lunch, afternoon snack, and dinner, in addition to sweets. Portions taken were estimated using Nasco® food replicas. A food database was prepared, and kilocalories were estimated based on data reported for each food in the manual of the Mexican system of food equivalents12 and on the labels of sweets not included in the manual.

High-calorie diets were defined as a calorie consumption ≥30% than recommended, according to the criteria of the Dietary Guidelines for American, American Academy of Pediatrics Nutrition Handbook and the American Heart Association.13

Statistical analysisCategorical variables are given as frequencies, and continuous variables as mean and SD. Frequencies were compared using a Chi-square test, while markers were compared using a Mann–Whitney U test. Logistic regression and Spearman's correlation were used to determine the association between MS and all other variables. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant, and a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) was used. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22.0 software.

ResultsOf the 100 study subjects, 82 had obesity and 18 were overweight. The prevalence rate of MS was 73%, affecting 38 boys and 35 girls (p>0.05).

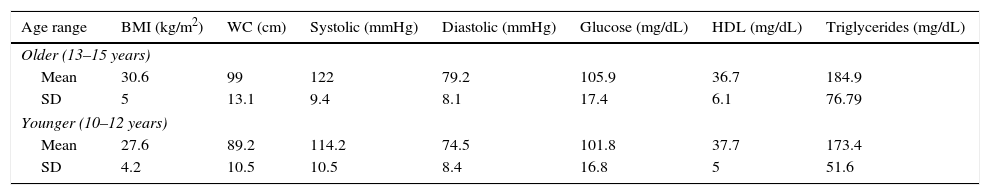

Table 1 shows the mean and SD of MS markers by age, including BMI, BP, glucose, HDL, and triglycerides.

Metabolic syndrome markers in children and adolescents with overweight or obesity by age category.

| Age range | BMI (kg/m2) | WC (cm) | Systolic (mmHg) | Diastolic (mmHg) | Glucose (mg/dL) | HDL (mg/dL) | Triglycerides (mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older (13–15 years) | |||||||

| Mean | 30.6 | 99 | 122 | 79.2 | 105.9 | 36.7 | 184.9 |

| SD | 5 | 13.1 | 9.4 | 8.1 | 17.4 | 6.1 | 76.79 |

| Younger (10–12 years) | |||||||

| Mean | 27.6 | 89.2 | 114.2 | 74.5 | 101.8 | 37.7 | 173.4 |

| SD | 4.2 | 10.5 | 10.5 | 8.4 | 16.8 | 5 | 51.6 |

WC: waist circumference; SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index.

n=60 older and 40 younger.

Both age groups had mean HDL levels (normal <40mg/dL) and triglyceride levels ≥150mg/dL, considered as hypertriglyceridemia by the International Diabetes Federation, with a value 11mg/dL in the older group.

AN prevalence was 73%. The condition was most commonly found in the back of the neck (45%), followed by the elbows (15%), knees (10%), and palms and soles (3%). According to the Simone et al. classification,12 1% had grade 1, 10% grade 2, 23% grade 3, and 39% grade 4 AN.

There were no sex differences, and frequency by age was similar in the older and younger groups (73.3% and 72.5% respectively, p<0.552).

Seventy-two percent of all subjects had concomitant MS and AN. Of these, 87.5% had LBW (≤2.500kg) and 8 (11.1%) had been macrosomic babies.

Eighty-seven percent of the total sample had a high calorie intake for age and sex. No study subject practiced exercise.

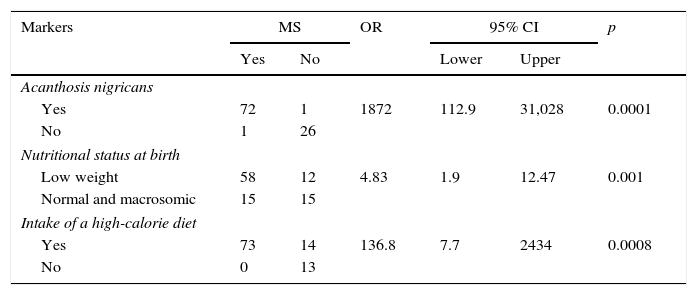

As shown in Table 2, MS was found to be associated to AN (p<0.0001), nutritional status at birth (p<0.001), and a high-calorie diet (p<0.0008).

Association of acanthosis nigricans, nutritional status at birth, and intake of a high-calorie diet with metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents with overweight and obesity.

| Markers | MS | OR | 95% CI | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Lower | Upper | |||

| Acanthosis nigricans | ||||||

| Yes | 72 | 1 | 1872 | 112.9 | 31,028 | 0.0001 |

| No | 1 | 26 | ||||

| Nutritional status at birth | ||||||

| Low weight | 58 | 12 | 4.83 | 1.9 | 12.47 | 0.001 |

| Normal and macrosomic | 15 | 15 | ||||

| Intake of a high-calorie diet | ||||||

| Yes | 73 | 14 | 136.8 | 7.7 | 2434 | 0.0008 |

| No | 0 | 13 | ||||

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; MS: metabolic syndrome.

n=100.

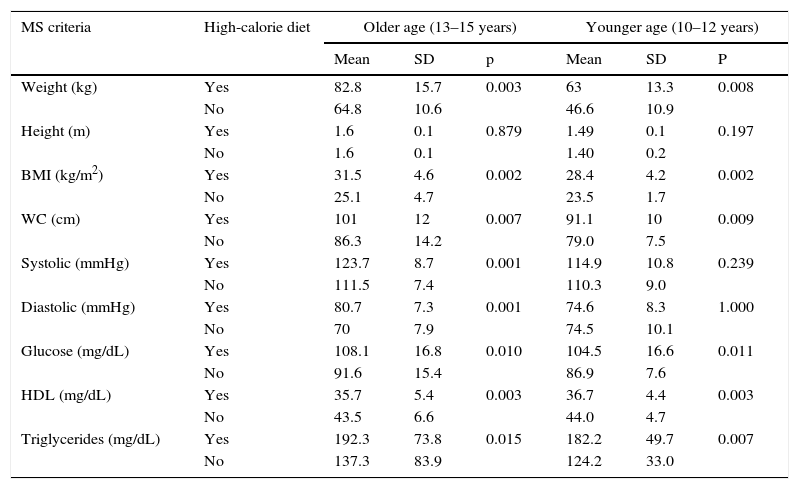

The older group with MS and AN had a mean and SD of calorie intake in the week end of 2707.8±291.3kcal (high-calorie diet), while the intake of subjects with no MS and AN was 2206.3±336.1kcal (p<0.001) (normal diet for boys and girls aged 13–15 years); in the younger group, the mean calorie consumption of those with association of both study variables exceeded the recommended daily intake of 2500.4±213.6kcal (high-calorie diet). The variables of weight, BMI, WC, glucose, HDL, and triglycerides for MS, by age category, were found to be more altered when a high-calorie diet was taken (see Table 3).

Comparison of metabolic syndrome criteria to high-calorie diet in children and adolescents with overweight or obesity by age group.

| MS criteria | High-calorie diet | Older age (13–15 years) | Younger age (10–12 years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | p | Mean | SD | P | ||

| Weight (kg) | Yes | 82.8 | 15.7 | 0.003 | 63 | 13.3 | 0.008 |

| No | 64.8 | 10.6 | 46.6 | 10.9 | |||

| Height (m) | Yes | 1.6 | 0.1 | 0.879 | 1.49 | 0.1 | 0.197 |

| No | 1.6 | 0.1 | 1.40 | 0.2 | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | Yes | 31.5 | 4.6 | 0.002 | 28.4 | 4.2 | 0.002 |

| No | 25.1 | 4.7 | 23.5 | 1.7 | |||

| WC (cm) | Yes | 101 | 12 | 0.007 | 91.1 | 10 | 0.009 |

| No | 86.3 | 14.2 | 79.0 | 7.5 | |||

| Systolic (mmHg) | Yes | 123.7 | 8.7 | 0.001 | 114.9 | 10.8 | 0.239 |

| No | 111.5 | 7.4 | 110.3 | 9.0 | |||

| Diastolic (mmHg) | Yes | 80.7 | 7.3 | 0.001 | 74.6 | 8.3 | 1.000 |

| No | 70 | 7.9 | 74.5 | 10.1 | |||

| Glucose (mg/dL) | Yes | 108.1 | 16.8 | 0.010 | 104.5 | 16.6 | 0.011 |

| No | 91.6 | 15.4 | 86.9 | 7.6 | |||

| HDL (mg/dL) | Yes | 35.7 | 5.4 | 0.003 | 36.7 | 4.4 | 0.003 |

| No | 43.5 | 6.6 | 44.0 | 4.7 | |||

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | Yes | 192.3 | 73.8 | 0.015 | 182.2 | 49.7 | 0.007 |

| No | 137.3 | 83.9 | 124.2 | 33.0 | |||

WC: waist circumference; SD: standard deviation; HDL: high density lipoprotein; BMI: body mass index; MS: metabolic syndrome.

Older subjects with high-calorie diets 52, excluding 8; younger subjects with high-calorie diets 34, excluding 6.

n=60 older and 40 younger.

In Mexico, LBW is found in 8.37% of children under 5 years of age.4 The reason for the high proportion found in our study population is that they come from a third level concentration hospital attended by a population with very low income and no health care system.

Subjects enrolled into this study were selected among those attending the obesity clinic because of their greater adiposity, which accounts for the high frequency of MS as compared to other studies of prevalence in children and adolescents in the general population.14–17

The more frequent MS markers included WC, increased serum glucose levels, and altered systolic and diastolic BP.

Obese subjects studied had a high frequency of LBW, which supports the Barker et al. theory of “fetal programming” for development of metabolic changes.2

Prior studies suggest than intrauterine nutrition and LBW may be predictors of diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease in adulthood,18,19 promoted by convergent environmental factors.4

It has been suggested that the implication of LBW in adiposity is due to development of the hypothalamic appetite center, which leads to overnutrition and obesity in postnatal life. Subjects with LBW may possibly metabolically limit their energy expenditure from intrauterine life, which leads them to develop the thrifty phenotype.19

Inconsistencies between LBW and risk of obesity in later life have been answered by a more recent study in Chinese children and adolescents suggesting that LBW is associated to a greater chance of obesity and, in subjects with very LBW, to a greater trend to central obesity.20

The Pune Maternal Nutrition Study, conducted in India in children with LBW, monitored children from 4 to 8 years of age and confirmed that they had high levels of adiposity, AO, IR, and cardiovascular risk factors, thus supporting the previous findings.21

Despite the relationship found between LBW and obesity, as well as other metabolic changes such as hyperinsulinemia,22 the exact relationship between birth weight and MS in childhood and adolescence is still unclear.

Participation of environmental and social conditions, related to nutritional imbalance in adult age, is being evaluated.23

The association found between AO and changes in MS components in children and adolescents also suggests a risk similar to that reported by Weiss et al.,17 the Bogalusa Heart Study,10 and Freedman et al.24–26

In this same regard, Yuan et al. found in China an association between LBW and AO (OR: 2.3; 95% CI: 1.03–5.14), as compared to newborns of greater weight, adjusted for gestational age and prenatal and diabetic factors.20

We found data similar to those in the Barker19 and DOHaD18 studies with regard to metabolic changes with LBW, which are in turn associated to obesity.

Evaluation of AO is a strong marker of central adiposity for diagnosis of metabolic changes.25 As shown in this study, WC is a better estimator of AO.

The relationship between excess adiposity in adults, predisposing to a high risk of diabetes, and metabolic disorders is largely based on the newborns with LBW and AO, who appear to have a greater risk of diabetes since their gestational life.22

Our results support the association of LBW to risk of MS and AO, suggesting the participation of potential pathophysiological and inflammatory factors related to MS in pregnancy, childhood, and adolescence.1,19 Such factors condition a high probability of development of diabetes.

Intake of a high-calorie diet as part of the lifestyle is closely related to presence of MS,27 a condition which, because of their characteristics, requires a larger sample size to support the idea.

Few studies are available on the prevalence of AN in children and adolescents, and the condition appears to be strongly related to metabolic problems.28

AN has been considered as a clinical sign of risk of MS,29 and its importance lies in its correlation to IR,30 as shown by the association found between MS and AN. Our findings contribute to consider AN as a clinical sign of risk of MS and as a marker of metabolic changes for MS.

The association of MS and high-calorie diet in this study has as limitation a wide 95% CI. Larger sample sizes and cohort studies are therefore suggested to support this hypothesis, as well as assessment of the risk of MS and AN with adjustment for gestational age, sex, socioeconomic level, and education, among other social conditions.

Finally, we think that determination of risk factors for MS is essential to take preventive measures, including lifestyle changes, in high risk populations such as subjects with LBW.

ConclusionsLBW is a warning sign, according to fetal programming; it is seen to facilitate distribution of central adiposity when combined with frequent intake of high-calorie diets at early age, thus promoting endocrine and metabolic changes, including MS and AN.

LBW, AN, and high-calorie intake were associated to MS in subjects with overweight and obesity at early ages.

Conflicts of interestThe authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Velazquez-Bautista M, López-Sandoval JJ, González-Hita M, Vázquez-Valls E, Cabrera-Valencia IZ, Torres-Mendoza BM. Asociación del síndrome metabólico con bajo peso al nacimiento, consumo de dietas hipercalóricas y acantosis nigricans en escolares y adolescentes con sobrepeso y obesidad. Endocrinol Nutr. 2017;64:11–17.