The development of massive sequencing techniques and guidelines for assessing the pathogenicity of variants are allowing us the identification of new cases of Familial Chylomicronemia (FCH), mostly in the LPL gene, less frequently in GPIHBP1 and APOA5, and with even fewer cases in LMF1 and APOC2. From the included studies, it can be deduced that, in cases with Multifactorial Chylomicronemia Syndrome (MCS), both loss-of-function variants and common variants in canonical genes for FCH contribute to the manifestation of this other form of chylomicronemia. Other common and rare variants in other triglyceride metabolism genes have been identified in MCS patients, although their real impact on the development of severe hypertriglyceridemia is unknown. There may be up to 60 genes involved in triglyceride metabolism, so there is still a long way to go to know whether other genes not discussed in this monograph (MLXIPL, PLTP, TRIB1, PPAR alpha or USF1, for example) are genetic determinants of severe hypertriglyceridemia that need to be taken into account.

El desarrollo de las técnicas de secuenciación masiva y las guías para la valoración de la patogenicidad de las variantes está permitiendo la identificación de nuevos casos con Quilomicronemia Familiar (QF), mayoritariamente en el gen LPL, con menor frecuencia en GPIHBP1 y APOA5 y aún con menor número de casos en LMF1 y APOC2. De los estudios consultados puede deducirse que, en los casos con Síndrome de Quilomicronemia Multifactoria (SQM)l, tanto las variantes de pérdida de función como las variantes comunes en los genes canónicos para QF contribuyen a la manifestación de esta otra forma de quilomicronemia. Otras variantes comunes y raras en otros genes del metabolismo de triglicéridos se han identificado en los pacientes con SQM, si bien, no se conocen su impacto real en el desarrollo de la hipertrigliceridemia grave. Puede haber hasta 60 genes implicados en el metabolismo de los triglicéridos, por lo que queda aún un largo camino por recorrer para saber si otros genes no tratados en este monográfico (MLXIPL, PLTP, TRIB1, PPAR alfa o USF1, por ejemplo) son determinantes genéticos de las hipertrigliceridemias graves que son necesarios tener en cuenta.

The relationship between plasma triglyceride (TG) levels and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) has been supported by scientific evidence, with the result that the increased risk of ASCVD is already relevant with fasting plasma TG levels of 150 mg/dl or more,1 and hypertriglyceridaemia (HTG) is considered severe with levels above 1000 mg/dl.2 Elevated circulating TG occurs as a consequence of an alteration in the metabolism of the lipoproteins that transport them which could be chylomicrons (Cms), very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) and intermediate-density lipoproteins (IDL). The more compromised the lipolysis process is, compared to the di novo overproduction of these lipoproteins, the greater the probability of accumulating CMs while fasting (chylomicronaemia) and of presenting severe HTG.3

The heritability of the different HTG phenotypes has been estimated at 50%4 and has been classically differentiated between primary and secondary HTG based on the predominantly genetic or environmental aetiology, respectively.5 In the context of severe HTG, where the hereditary component is more likely, 2 clinical entities are distinguished: familial chylomicronemia (FCH) and multifactorial chylomicronemia syndrome (MCS). These 2 entities, together with familial partial lipodystrophy (FPLD), a disorder of genetic origin that can present with severe HTG,6 share clinical features such as episodes of acute pancreatitis, undoubtedly the most serious consequence of chylomicronemia, although they differ in the type of inheritance (the genes and sequence variants involved in its development), prevalence, age of onset of symptoms and recurrence of pancreatitis.

Different experimental strategies such as studies in animal models or genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques have revealed the involvement of multiple genetic variants and up to 60 genes in TG metabolism, including: LPL, GPIHBP1, APOA5, LMF1, APOC2, APOC3, APOE, GCKR, GPD1, ANGPTL3, CREB3L3 and GALNT2.7 The analysis of the functional impact of these genetic variants is essential to understand their contribution to the manifestation of chylomicronaemia.

Pathogenic, benign sequence variants or those of uncertain significanceThe concept of pathogenicity of genetic variants is not new, although the way it is assessed and used to facilitate the diagnosis of diseases of genetic origin, including primary dyslipidaemias such as the forms of chylomicronaemia mentioned above, is more recent.

In 2015, the American College of Genetic Medicine and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG/AMP) proposed a classification system based on standard criteria of pathogenicity and benignity obtained from scientific evidence.8 Both in the standards described in that document and in the guidelines of the Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS), the terms “mutation” and “polymorphism” are considered obsolete, as they have been classically associated with pathogenicity or loss of function (“rare” variants) and benignity (“common” variants), respectively. Instead, the HGVS proposes the use of “variant,” “variation,” or “change,” regardless of the associated functional impact, while the ACMG standards define 5 categories for classification from greatest to least or no functional effect: pathogenic, probably pathogenic, variants of uncertain significance, probably benign, or benign.

The recommendations described for the assessment of the weight (“strength”) assigned to the different pathogenicity/benignity criteria (https://clinicalgenome.org/working-groups/sequence-variant-interpretation/) and the development of bioinformatics predictors, capable of collecting information from multiple databases simultaneously, have encouraged the ACMG standards to be the ones with the greatest consensus in the literature and which are used in the reporting of genetic study findings.9

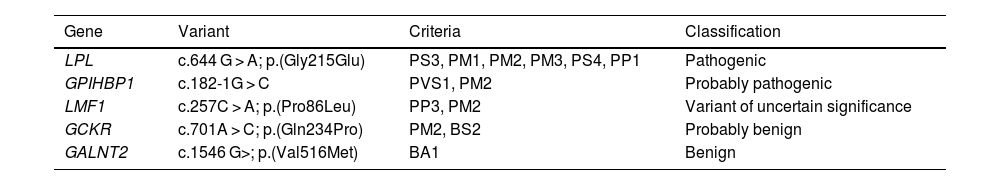

The ACMG defines numerous criteria which are dependent upon the type of evidence applicable in each case: functional data, effect on the protein, in silico predictions or allele frequency data, among others8 (Table 1). The criteria with the greatest weight for pathogenicity may be PS3 and PVS1, that support the loss of function of the gene in question. In the examples in Table 1, the variant with the greatest number of applicable criteria is p.(Gly215Glu) in the lipoprotein lipase gene (LPL), which is the most frequent in subjects with FCH, also in Spain.10 Criterion BA1 has great weight in the opposite direction: the high allele frequency (4.5%) supports the benignity of the variant to which it is assigned, although it is not excluded that it may have a functional effect, that is, a discrete phenotypic impact.

Example of the 5 gene variant categories defined by the ACMG.

| Gene | Variant | Criteria | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| LPL | c.644 G > A; p.(Gly215Glu) | PS3, PM1, PM2, PM3, PS4, PP1 | Pathogenic |

| GPIHBP1 | c.182-1G > C | PVS1, PM2 | Probably pathogenic |

| LMF1 | c.257C > A; p.(Pro86Leu) | PP3, PM2 | Variant of uncertain significance |

| GCKR | c.701A > C; p.(Gln234Pro) | PM2, BS2 | Probably benign |

| GALNT2 | c.1546 G>; p.(Val516Met) | BA1 | Benign |

BA1: high allele frequency; BP4: in silico prediction of benignity; BS2: variant observed in homozygosity in healthy subjects; PM1: the variant is located in a mutational hotspot; PM2: very low population allele frequency (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/); PM3: variant found in trans (compound heterozygosity) with other pathogenic variants; PP1: biallelic cosegregation with the phenotype; PP3: in silico prediction of pathogenicity; PS3: functionality studies testing loss of protein function; PS4: variant with higher allele frequency than expected for the phenotype; PVS1: null variant affecting gene translation.

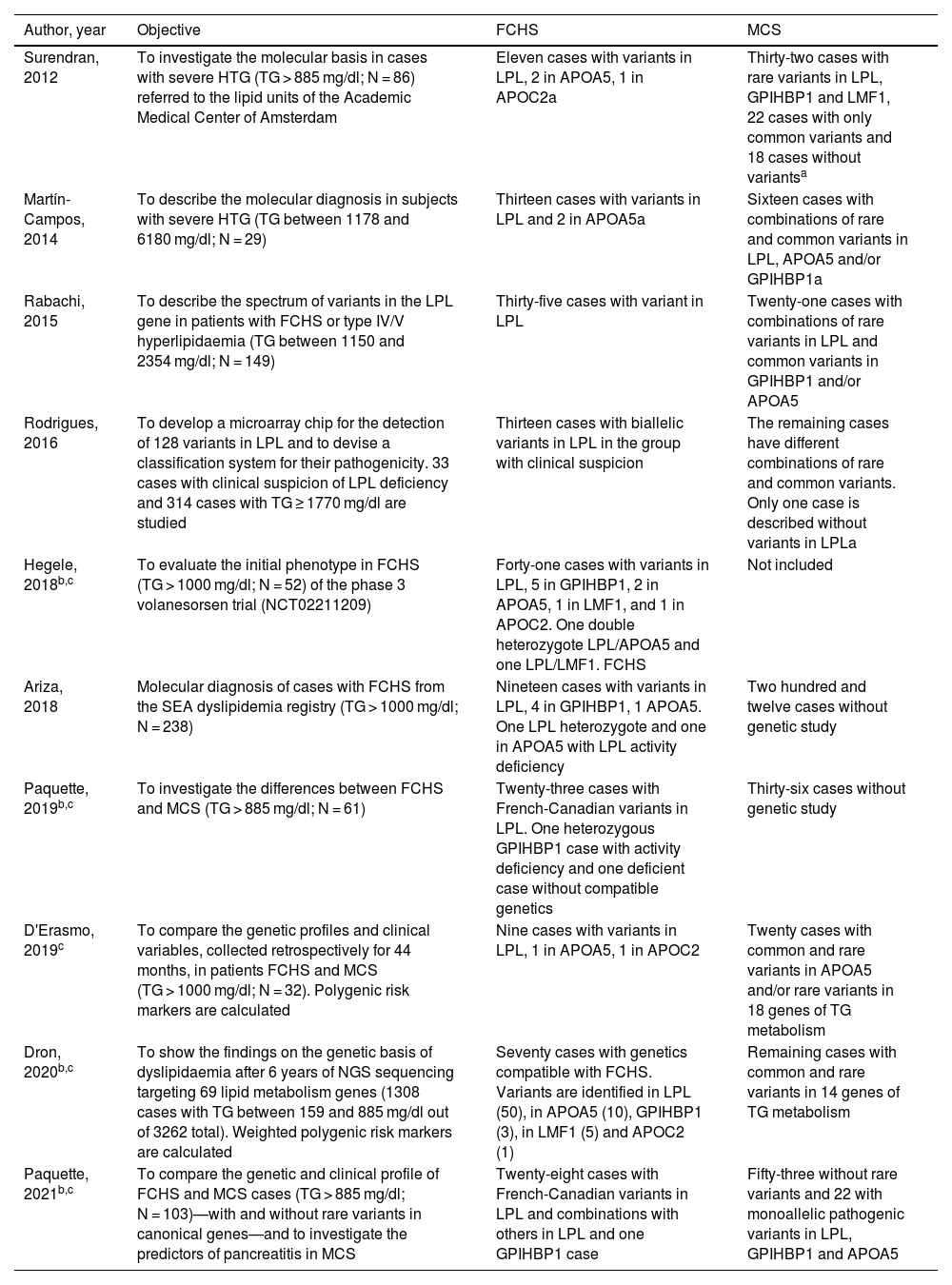

Regardless of the epidemiological, biochemical and clinical differences between these two forms of chylomicronaemia, genetic testing is the gold standard for distinguishing between them, and is necessary to confirm or rule out the clinical diagnosis of FCH.11Table 2 lists 10 studies performed on subjects with severe HTG and showing differential characteristics between FCH and MCS.7,10,12–14

Main findings of genetic studies performed in different cohorts of patients with severe hypertriglyceridaemia.

| Author, year | Objective | FCHS | MCS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surendran, 2012 | To investigate the molecular basis in cases with severe HTG (TG > 885 mg/dl; N = 86) referred to the lipid units of the Academic Medical Center of Amsterdam | Eleven cases with variants in LPL, 2 in APOA5, 1 in APOC2a | Thirty-two cases with rare variants in LPL, GPIHBP1 and LMF1, 22 cases with only common variants and 18 cases without variantsa |

| Martín-Campos, 2014 | To describe the molecular diagnosis in subjects with severe HTG (TG between 1178 and 6180 mg/dl; N = 29) | Thirteen cases with variants in LPL and 2 in APOA5a | Sixteen cases with combinations of rare and common variants in LPL, APOA5 and/or GPIHBP1a |

| Rabachi, 2015 | To describe the spectrum of variants in the LPL gene in patients with FCHS or type IV/V hyperlipidaemia (TG between 1150 and 2354 mg/dl; N = 149) | Thirty-five cases with variant in LPL | Twenty-one cases with combinations of rare variants in LPL and common variants in GPIHBP1 and/or APOA5 |

| Rodrigues, 2016 | To develop a microarray chip for the detection of 128 variants in LPL and to devise a classification system for their pathogenicity. 33 cases with clinical suspicion of LPL deficiency and 314 cases with TG ≥ 1770 mg/dl are studied | Thirteen cases with biallelic variants in LPL in the group with clinical suspicion | The remaining cases have different combinations of rare and common variants. Only one case is described without variants in LPLa |

| Hegele, 2018b,c | To evaluate the initial phenotype in FCHS (TG > 1000 mg/dl; N = 52) of the phase 3 volanesorsen trial (NCT02211209) | Forty-one cases with variants in LPL, 5 in GPIHBP1, 2 in APOA5, 1 in LMF1, and 1 in APOC2. One double heterozygote LPL/APOA5 and one LPL/LMF1. FCHS | Not included |

| Ariza, 2018 | Molecular diagnosis of cases with FCHS from the SEA dyslipidemia registry (TG > 1000 mg/dl; N = 238) | Nineteen cases with variants in LPL, 4 in GPIHBP1, 1 APOA5. One LPL heterozygote and one in APOA5 with LPL activity deficiency | Two hundred and twelve cases without genetic study |

| Paquette, 2019b,c | To investigate the differences between FCHS and MCS (TG > 885 mg/dl; N = 61) | Twenty-three cases with French-Canadian variants in LPL. One heterozygous GPIHBP1 case with activity deficiency and one deficient case without compatible genetics | Thirty-six cases without genetic study |

| D'Erasmo, 2019c | To compare the genetic profiles and clinical variables, collected retrospectively for 44 months, in patients FCHS and MCS (TG > 1000 mg/dl; N = 32). Polygenic risk markers are calculated | Nine cases with variants in LPL, 1 in APOA5, 1 in APOC2 | Twenty cases with common and rare variants in APOA5 and/or rare variants in 18 genes of TG metabolism |

| Dron, 2020b,c | To show the findings on the genetic basis of dyslipidaemia after 6 years of NGS sequencing targeting 69 lipid metabolism genes (1308 cases with TG between 159 and 885 mg/dl out of 3262 total). Weighted polygenic risk markers are calculated | Seventy cases with genetics compatible with FCHS. Variants are identified in LPL (50), in APOA5 (10), GPIHBP1 (3), in LMF1 (5) and APOC2 (1) | Remaining cases with common and rare variants in 14 genes of TG metabolism |

| Paquette, 2021b,c | To compare the genetic and clinical profile of FCHS and MCS cases (TG > 885 mg/dl; N = 103)—with and without rare variants in canonical genes—and to investigate the predictors of pancreatitis in MCS | Twenty-eight cases with French-Canadian variants in LPL and combinations with others in LPL and one GPIHBP1 case | Fifty-three without rare variants and 22 with monoallelic pathogenic variants in LPL, GPIHBP1 and APOA5 |

FCHS: cases with compatible genetics: biallelic pathogenic variants; MCS: cases with monoallelic pathogenic/rare variants (allelic frequency < 1%) and common variants.

The designation FCHS/MCS is not used. The number of FCHS or MCS cases is inferred from the study data.

NGS is used in these studies. Sanger sequencing is used in the other studies. The variants considered French-Canadian by the authors of the studies are p.(Pro234Leu) and p.(Gly215Glu), categorised in Fig. 1.

FCH―familial hyperpoproteinaemia type I15 is a rare monogenic disease, with recessive inheritance, caused by the presence of biallelic combinations of pathogenic or probably pathogenic variants in one of the genes directly involved in the hydrolysis of TG: LPL, GPIHBP1, APOC2, APOA5 or LMF1. The direct consequence of these genetic alterations is the deficiency of LPL activity. The definition of cut-off points in activity values to consider that the deficit is important constitutes a test of the functionality of the variants that, when the results of the genetic study are not conclusive, is necessary to confirm or not the pathogenicity of the identified variants.10,13,16

MCS―hyperpoproteinaemia type V has a polygenic and multifactorial origin. Its appearance is a consequence of the combination of multiple genetic variants in genes of the metabolism of TG,11 both pathogenic (in heterozygosis or monoallelic) and benign, together with secondary factors that predispose to HTG including obesity, alcohol intake or poorly controlled diabetes.14

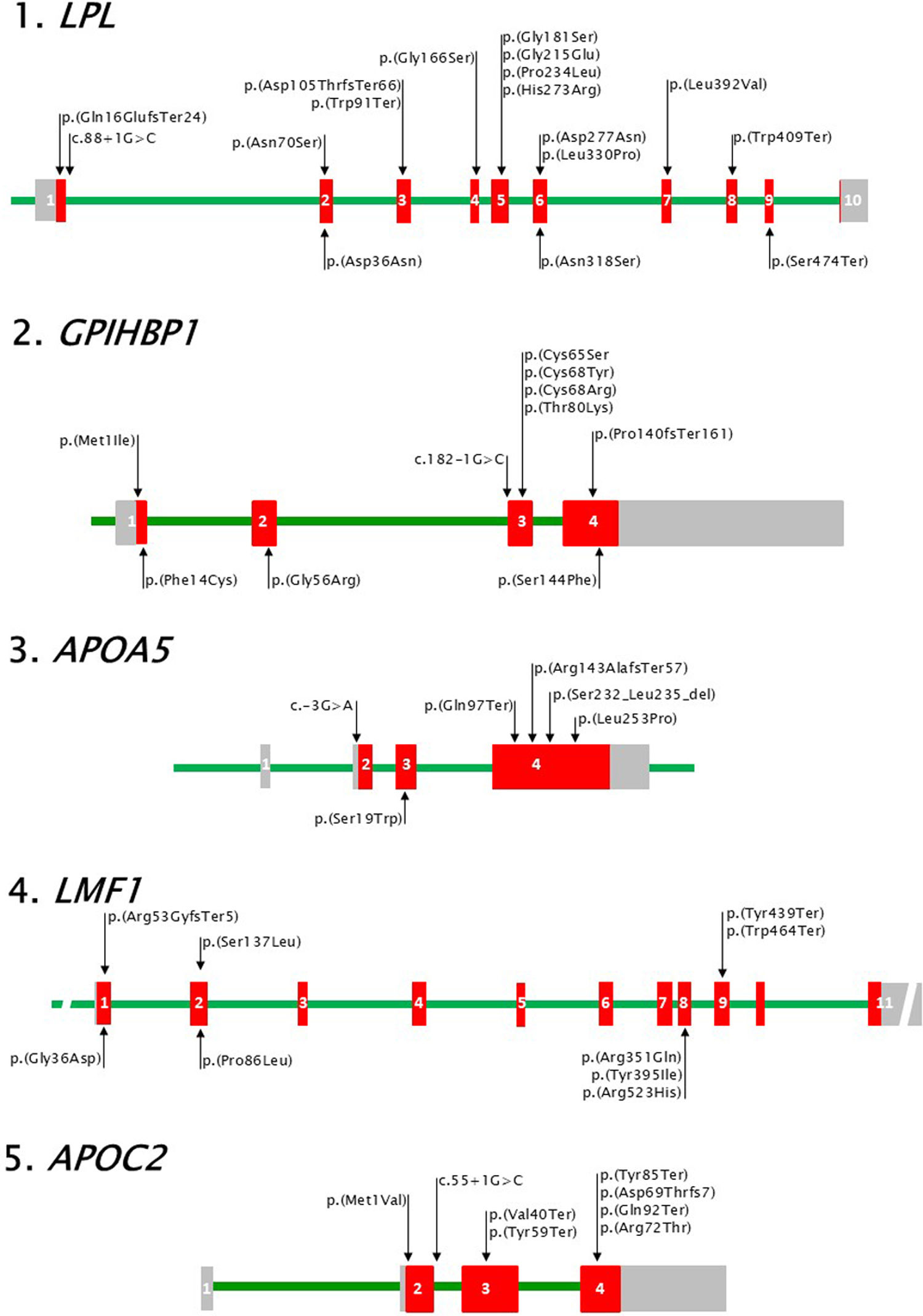

Canonical genes for familial chylomicronaemiaIt is known that the enzyme LPL hydrolyses most of the TG that reach the systemic circulation packaged in lipoproteins,17 and that to exert its lipolytic activity it requires the participation of glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-anchored HDL-binding protein 1 (GPIHBP1), apolipoproteins AV (ApoAV) and CII (ApoCII), and lipase maturation factor 1 (LMF1). These 5 proteins are encoded respectively by the genes LPL, GPIHBP1, APOA5, APOC2 and LMF1, which, as already mentioned, are the genes involved in the manifestation of FCHS; that is, canonical genes (Fig. 1).

Visual representation of canonical genes for FCHS.

Coding exonic regions (red rectangles), 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (grey rectangles) and introns (green line) are represented with approximate proportional size within each gene. Loss-of-function variants in each gene are shown at the top of the graph for each gene above the corresponding exon (numbered in white) and intron. Common benign variants are similarly represented at the bottom. 1. LPL, HGNC code: 6677. Reference sequences: NG_008855.2 (28007 base pairs -bp-), NM_000237.3 (3565 bp) and NP_000228.1 (475 amino acids -aas-). 2. GPIHBP1, HGNC code: 24945. Reference sequences: NG_034256.1 (3953 bp), NM_178172.6 (2257 bp) and NP_835466.2 (184 aas). 3. APOA5, HGNC code: 17288. Reference sequences: NG_015894.2 (2513 bp), NM_001371904.1 (1881 bp) and NP_001358833.1 (366 aas). 4. LMF1, HGNC code: 14154. Reference sequences: NG_021286.2 (117351 bp), NM_022773.4 (2606 bp) and NP_073610.2 (567 aas). 5. APOC2, HGNC code: 609. Reference sequences: NG_008837.1 (3515 bp), NM_000483.5 (660pb) and NP_000474.2 (101 aas). Variants are represented with the nomenclature NP_# (p._ for coding variants) or NM_# (c._ for intronic variants). HGNC: https://www.genenames.org/.

The LPL gene (HGNC code “Human Genome Organization Gene Nomenclature Committee”: 6677) is mainly expressed in muscle and adipose tissue, which are the main recipients of the fatty acids released after the hydrolysis of TG by LPL, which is secreted into the interstitial space and reaches the lumen of the blood capillaries thanks to GPIHBP1, with which it continues to interact to remain stabilized on the endothelial surface.

In accordance with the central role that LPL plays in the lipolytic cascade, more than 80% of the genetic variants causing FCH have been identified in this gene (Table 2).16,18 The alterations that they cause in the different functional domains of LPL explain the functional effect of these variants and support their pathogenicity classification.

Fig. 1 shows a visual representation of the LPL gene and some of the sequence variants identified. The most frequent form of pathogenic variation in LPL are missense amino acid variants concentrated in exon 5 of the gene, which, together with the absence of benign variants, make it a mutational hot spot. Furthermore, the amino acids encoded in exons 5 and 6 of LPL are located in the catalytic domain of the enzyme and close to the catalytic triad.19 Frameshift variants have also been described in LPL, such as the c.46-74del; p.(Gln16GlufsTer24) variant in exon 1 or the c.312delA; p.(Asp105ThrfsTer66) in exon 3, and variants in the intron/exon border regions, for example, the variant in intron 1: c.88+1, which cancel the transcription of the gene and, therefore, cause a total absence of LPL.10 Premature terminations ("nonsense") have also been identified, such as the variant c.1227; p.(Trp409Ter), in patients with activity deficit and low mass of LPL.20 Both in LPL, as in the rest of the genes referred to, copy number variants ("CNV") have been described in a lower proportion than the previous ones.13,21

In addition to the pathogenic variants of LPL that cause FCH, common variants associated with a TG-elevating effect have been described in this gene, which in certain situations can also alter the function of the enzyme by decreasing its secretion, hindering the interaction with GPIHBP1 or reducing catalytic activity. Fig. 1 shows, for example, the variant c.106G>A; p.(Asp36Asn), which is associated with a decrease in the secretion of the enzyme and c.953ª>G; p.(Asn318Ser), which also causes a lower secretion of LPL and a reduced catalytic capacity.22 Both variants appear more frequently in cases with HTG and also in patients with chylomicronaemia, as can be inferred from the studies listed in Table 2.

Finally, the premature termination c.1421C>A; p.(Ser474Ter) is the most frequent benign variant identified in LPL. The loss of the 2 amino acids of the enzyme is associated with a gain of function, that is, a lowering effect on TG levels and greater LPL activity. Recent studies suggest that part of its functional effect may be due to the fact that this variant is linked to others located in the 3ʹ. Untranslated region of the gene that would favour its expression.23

GPIHBP1 geneThe GPIHBP1 gene (HGCN code: 24945) is mainly expressed in the capillary endothelium. Its function is essential in the lipolytic cascade since it acts as a transporter for LPL to reach the vascular endothelium from the cells where it is produced. In addition, GPIHBP1 provides a binding platform for LPL in the endothelium necessary to be able to carry out its lipolytic activity.24

GPIHBP1 belongs to the Ly6 family of proteins, named after the 10-cysteine domain (lymphocyte antigen 6 domain) that forms disulfide bridges and forms a characteristic 3-finger structural motif. This domain, encoded by exons 3 and 4, is involved in binding to LPL and promotes contact between the enzyme and its substrate (TG-rich lipoproteins) through interaction with its activators, the apolipoproteins ApoCII and ApoAV. Also essential are the N-terminal acidic domain, encoded by exon 2, and the C-terminal domain (exon 4) that forms the covalent binding site to glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol (GPI anchor), important for the redirection of GPIHBP1 to the capillary endothelium.19,24

Most of the pathogenic variants described in GPIHBP1 affect the Ly6 domain and are mainly substitutions of cysteine residues such as the variant c.203 G > A; p.(Cys67Tyr) or nearby amino acids such as c.239C > A; p.(Thr80Lys)21 (Fig. 1.3–1.5). These variants have been found in homozygosity or compound heterozygosity in cases with QF that show a deficit of LPL activity and, significantly, a lower amount of enzyme (LPL mass) than cases with variants in LPL or APOA5, which supports the pathogenicity of these variants since it confirms an alteration in the LPL binding capacity and, therefore, affects its translocation to the endothelium.10,21

Furthermore, as in LPL, pathogenic variants have been identified in GPIHBP1 in the intron/exon junction areas25 and reading frame shifts,26 in addition to other variants that are not causal of FCHS but are associated with a tTG-elevating effect21 and are listed in Fig. 1.3–1.5.

APOA5 geneThe APOA5 gene (HGNC code: 17288) is located in the APOC1-APOC3-APOA4-APOA5 gene cluster on chromosome 11 and is expressed in the liver. Its effect on TG metabolism has been widely studied and it has recently been described that ApoAV activates LPL by selectively suppressing the inhibition of the enzyme by the ANGPTL3/8 complex while exerting a modulating effect on ApoAV through its interaction with GPIHBP1 that facilitates the lipolytic activity of LPL. In addition, ApoAV participates in the uptake of lipoproteins by hepatic receptors and regulates the secretion of TG synthesised in the liver.27

The role of APOA5 genetic variants in the development of FCHS is currently beyond doubt. Fig. 1.3 shows different types of variants in this gene that have been identified in patients with severe HTG, both in patients with QF (biallelic pathogenic) and in MCS cases (monoallelic pathogenic and benign functional). The most frequent pathogenic variants in the gene are premature terminations such as, for example, c.289C>T; p.(Gln97Ter).

The fact that the deficit of LPL activity in patients with pathogenic variants in APOA5 is masked by the addition of an external source of apolipoprotein in the activity assay16 makes it difficult to attribute pathogenicity to some variants. In these cases, an alternative activity assay is required to determine whether the altered ApoAV in these patients is capable of activating the LPL activity of a healthy subject. On the other hand, in vitro studies have been described (Mendoza Barberá) to demonstrate the loss of function of the "missense" variant c.757G>A; p.(Leu253Pro) one of the most frequent pathogenic variants in APOA5.

Finally, it is important to highlight that the variants in APOA5, in addition to having a TG-elevating effect, have been associated with the presence of ASCVD, such as the c.-3G>A variant in exon 2.28 Furthermore, in patients with MCS, the combination of monoallelic pathogenic variants and benign functional variants in this gene are more frequent than similar combinations in the other canonical genes for FCH.7

LMF1 geneThe LMF1 gene (HGNC code: 14154) is ubiquitously expressed. LMF1 is a protein containing 5 transmembrane domains connected by 4 loops, 2 of them facing the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum and 2 facing the cytoplasm. In addition, the protein has a conserved C-terminal domain. LMF1 is necessary for post-transcriptional modifications of LPL and it has been proposed that it functions as an endoplasmic reticulum chaperone necessary for the correct folding and homodimer formation of the enzyme, although the underlying molecular mechanism is not fully understood.29

Pathogenic variants in this gene are rare and mostly premature terminations that have been identified in patients with LPL activity deficiency. These variants encode truncated proteins in which a large part of the C-terminal domain of the protein is lost, such as the variants c.1317C>G; p.(Tyr439Ter) and c.1391G>A; p.(Trp464Ter) present in Fig. 1.3.30

Amino acid change variants located in the loops between the transmembrane segments that are oriented towards the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum have also been described in patients with severe HTG, such as the variant c.257C>T; p.(Pro86Leu) in exon 2 of the gene, or the variant c.1184C>T; p.(Tyr395Ile). These changes are associated with a significant reduction in LPL activity, although it is controversial whether they can cause deficits, probably due to the difficulty of comparing activity measurements obtained from post-heparin plasma of patients with measurements obtained from in vitro experiments.31

APOC2 geneThe APOC2 gene (HGNC code: 609) is located in the APOE-APOC1-APOC4-APOC2 gene cluster on chromosome 19. It is primarily expressed in the liver and encodes apolipoprotein CII (101 amino acids). The mature protein, after cleavage of the 22 amino acids of the signal peptide, acts as a cofactor for LPL. The N-terminal domain encodes the amino acids involved in the interaction with lipoproteins. The C-terminal region encodes the residues necessary for LPL activation and appears to be involved in the conformational changes necessary for the accessibility of TG-rich lipoproteins to the enzyme active site.32

The absence of ApoCII causes a deficit in LPL activity, although enzymatic assays mask this, as occurs with the ApoAV deficiency mentioned above. A small number of pathogenic or benign variants have been described in APOC2, with few cases diagnosed as FCH as a result of the former. Most of these cases belong to families with a high proportion of consanguinity. Wolska et al. have described 24 variants and some of them have also been identified in related patient cohorts. Fig. 1.5 shows variants causing ApoCII deficiency such as c.1A>G; p.(Met1Val), in the start codon, known as ApoCII Paris.1 The variant in the intronic region c.55+1G>C has been identified in 2 family groups for which it is given the names ApoCIIHamburg and APOCIITokio. Premature terminations, frame shifts or amino acid changes illustrated in Fig. 1.5 also refer to the geographic area of origin, such as the variant c.255C>A; p.(Tyr85Ter), known as ApoCIIAucklan, in which the patient tested showed severe neurological disorders as a consequence of lipid encephalitis.

As in the previous canonical genes for FCH, pathogenic variants in APOC2 have been found in heterozygosis in cases with MCS (Table 2) although benign variants with a TG-elevating effect that contribute to the manifestation of MCS have not been described.

Non canonical genes for multifactorial chylomicronaemia syndromeThe APOC3 gene (HGNC code: 610) encodes apolipoprotein CIII (Apo-CIII), a glycoprotein involved in TG metabolism by inhibiting LPL activity, preventing hepatic clearance of TG-rich particles, and promoting the secretion of VLDL particles into the bloodstream. As discussed in another section of this article, APOC3 is the current therapeutic target for the treatment of FCH. The variants described in APOC3 are mostly loss-of-function variants that have a protective effect both in relation to TG levels and the risk of ASCVD.33 There are few gain-of-function variants described in the literature with a TG-elevating effect. Silbernagel et al. have described that the less frequent allele of the common variant c.*71G > T (allele G), in the 3ʹ. untranslated region, is associated with an increase in the concentration of ApoCIII and TG. Its functional effect may be due to the fact that it affects a binding site for the micro RNA miR-4271, so that the translation of the gene would not be repressed.34 This variant has not been reported in the context of severe HTG, so it is not possible to know its real influence on the manifestation of chylomicronaemia.

The APOE gene (HGNC code: 613) plays a central role in lipid metabolism. Apolipoprotein E is present in all lipoproteins, playing a key role in lipid transport and in the hepatic elimination of remnant particles mediated by the receptor. The common isoform ɛ4 [c.388T>C; [p.(Cys130Arg), rs429358] has been linked to TG and cholesterol levels, ACVD, and Alzheimer's disease. In addition, the ɛ2 isoform [c.562C>T; p.(Arg176Cys, rs7412] in homozygosis or other rare variants in the gene are required for the diagnosis of dysbetalipoproteinemia.35 However, the role of these variants in severe HTG is less known. Low allelic frequency variants in APOE have been identified in some of the studies cited in Table 2, although most are variants of uncertain significance and given their low frequency, it is not possible to know their contribution to the phenotype of severe HTG.

The GCKR gene (HGNC code: 4196) encodes the glucokinase regulatory protein. The relationship between variants of this gene and TG levels was discovered by GWAS studies performed in type 2 diabetes.36 The common variant c.1337T>C; p.(Leu446Pro), rs1260326, is associated with lower fasting glucose levels but higher TG concentrations due to elevated glucokinase activity and increased di novo lipogenesis. This and other rare and common variants in the gene have confirmed the association with TG concentration in healthy subjects. Likewise, new uncommon variants in GCKR have been identified in subjects with severe HTG whose functional effect is also unknown.7

Pathogenic variants in the gene encoding glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GPD1) have been described as causing transient infantile HTG, such as the variant in intron 3: c.361-1G>C. GPD1 which catalyses an oxidation-reduction reaction that produces glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P) and NAD+ from dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and NADH. Deficiency of this enzyme can cause steatosis and hepatic fibrosis, hepatomegaly, elevated liver enzymes, and HTG. Rare variants in this gene have also been reported in cases with severe HTG, although their real impact is unknown. In fact, some of them have allelic frequencies similar to those of healthy subjects.37

The ANGPTL3 gene (HGNC code: 491) encodes an angiopoietin 3-like protein, which is involved in the regulation of TG and glucose metabolism. This and other proteins in the family (ANGPT4 and ANGPTL8) have a TG-lowering effect by inhibiting LPL activity 45). Loss-of-function variants in this gene cause a decrease in most circulating lipoproteins. Furthermore, ANGPTL3 deficiency causes an increase in LPL activity.38 To our knowledge, no gain-of-function variants have been described in this gene or their effect on TG levels.

The CREB3L3 gene (HGNC code: 191) encodes the CREBH protein (cyclic AMP response element binding protein H), a transcription factor that regulates the expression of several TG metabolism genes, including APOA5, APOC2 and C3.39 Rare variants in this gene produce a dysfunctional protein. It has been reported that subjects with severe HTG present a significant accumulation of loss-of-function variants in this gene compared to healthy controls, although no FCH cases with biallelic variants in this gene have been published.

Finally, the GALNT2 gene (HGNC code: 4124) encodes for polypeptide-N-acetylgalactosamine transferase 2. This enzyme catalyses the O-glycosylation of a multitude of substrates, including apolipoprotein CIII, ANGPTL3 and phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP). Common and rare variants in GALNT2, of unknown functional impact, have been identified in cases with severe HTG (Table 1). Furthermore, the reduction in HDL cholesterol levels observed in patients with GALNT2 deficiency―severe neurological and developmental impairment―does not correspond to an increase in TG levels.40

ConclusionsThe development of massive sequencing techniques and guidelines for assessing the pathogenicity of variants is leading to the identification of new cases with FCH, mostly in the LPL gene, less frequently in GPIHBP1 and APOA5 and even less in LMF1 and APOC2. From the studies consulted, it can be deduced that in cases with MCS, both loss-of-function variants and common variants in canonical genes for FCH contribute to the manifestation of this other form of chylomicronaemia. Other common and rare variants in other genes of TG metabolism have been identified in patients with MCS, although their real impact on the development of severe HTG is not known. If, as discussed above, there may be up to 60 genes involved in TG metabolism, there is still a long way to go to know whether other genes not discussed in this monograph (e.g., MLXIPL, PLTP, TRIB1, PPAR alpha or USF1) are genetic determinants of severe HTG to be taken into account.

FundingThis work was funded by an unconditional grant from Sobi who did not participate in the design of the work or in the preparation of this manuscript.

Information about the supplementThis paper is part of the supplement entitled Severe hypertriglyceridaemia which has been funded by the Sociedad Española de Arteriosclerosis, with sponsorship from Sobi.

Please cite this article as: Ariza Corbo MJ, Muñiz-Grijalvo O, Blanco Echevarría A, Díaz-Díaz JL. Bases genéticas de las hipertrigliceridemias. Clin Investig Arterioscl. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arteri.2024.11.001