Statins are contraindicated in patients with myopathies. Until a few years ago, in those patients with familial hypercholesterolemia who also presented muscular dystrophies and did not reach adequate cholesterol plasmatic levels, the next therapeutic ladder was lipoapheresis. When iPCSK9 first appeared, lipoapheresis could be suspended in some of these patients, sustaining nevertheless proper levels of cholesterol.

We present the case of a 27 year-old male, diagnosed with congenital muscular dystrophy in the early childhood. He was referred to the Unit of Lipidology presenting hypercholesterolemia which, after genetic test, was assessed as heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Despite of treatment with diet and ezetimibe, cLDL blood levels abide high, being consequently included in lipoapheresis programme, therewith obtained levels of cLDL of 70mg/dl. In providing iPCSK9, lipoapheresis was withdrawn and treatment with alirocumab 150mg fortnightly introduced, unveiling a positive response, and sustaining cLDL levels around 75mg/dl.

Las estatinas están contraindicadas en pacientes con miopatías. Hasta hace unos años, la alternativa en pacientes con hipercolesterolemia familiar que tenían distrofias musculares y no conseguían niveles adecuados de colesterol era la lipoaféresis. Cuando surgieron los inhibidores de PCSK9, se consiguió suspender la lipoaféresis en algunos de estos pacientes y mantenerlos con concentraciones plasmáticas de colesterol adecuadas.

Presentamos el caso de un varón, diagnosticado en la infancia de distrofia muscular congénita. A los 27 años se remitió a la unidad de lípidos por hipercolesterolemia, donde tras estudio genético se confirmó una hipercolesterolemia familiar heterocigota. A pesar del tratamiento con dieta y ezetimiba continuó con cifras elevadas de cLDL por lo que se incluyó en programa de lipoaféresis. Con esto se alcanzaron niveles de cLDL de 70mg/dl. Al disponer de los iPCSK9, se suspendió la lipoaféresis y se inició tratamiento con alirocumab 150mg quincenal, con buena respuesta y manteniendo valores de cLDL en torno a 75mg/dl.

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is the most common autosomal dominant genetic disease. It is caused by the mutation of some of the genes that participate in the catabolism of cholesterol bound to low density lipoproteins (cLDL), the most frequent being the one that codes for the LDL receptor. HF is characterised by elevated levels of cLDL and a propensity for early atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Case reportWe present the case of a 27-year-old male, diagnosed in childhood by genetic study with centronuclear myopathy type muscular dystrophy (recessive inheritance linked to the X chromosome) with inability to take statins. He started at 7 months with hypotonia and skeletal muscle weakness. He was admitted several times due to respiratory failure secondary to the respiratory muscle weakness that occurs. He is currently partially dependent for the basic activities of daily life and walks without help.

Referred to the Lipids Unit of the Hospital San Pedro, Logroño, La Rioja, Spain, because in November 2010 he experienced a total cholesterol (TC) of 286mg/dl and cLDL of 229mg/dl. Both his mother and one of his sisters had higher levels of cLDL than 250mg/dl, despite receiving a pharmacological treatment.

The patient had no known allergies, was a smoker of 5 cigarettes/day and drank some beer occasionally. He had a congenital muscular dystrophy, a type of centronuclear myopathy diagnosed by muscle biopsy at 10 years of age. Physical examination: body mass index: 23.8kg/m2 and blood pressure: 138/91mmHg. There was no presence of corneal arch, xanthomas or xanthelasmas. Both cardiac and pulmonary auscultation, and the abdominal examination were normal.

A new analysis confirmed hypercholesterolemia: TC: 304mg/dl; cLDL: 235mg/dl; triglycerides: 115mg/dl; cHDL: 46mg/dl; apolipoprotein B (apoB): 153mg/dl; apolipoprotein A1: 146mg/dl and lipoprotein (a): 12mg/dl. The ECG showed sinus tachycardia at 108bpm, without other alterations simple chest and abdomen X-rays showed no relevant alterations.

Treatment with a lipid-lowering diet and ezetimibe 10mg/day was started. When the objective levels of cLDL were not reached after this treatment, both the patient and his first-degree relatives were asked for a genetic study, identifying in him, in his mother and in one of his sisters a pathogenic mutation in heterozygous gene encoding the LDL receptor (M025+M080), therefore, he was diagnosed with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HeFH).

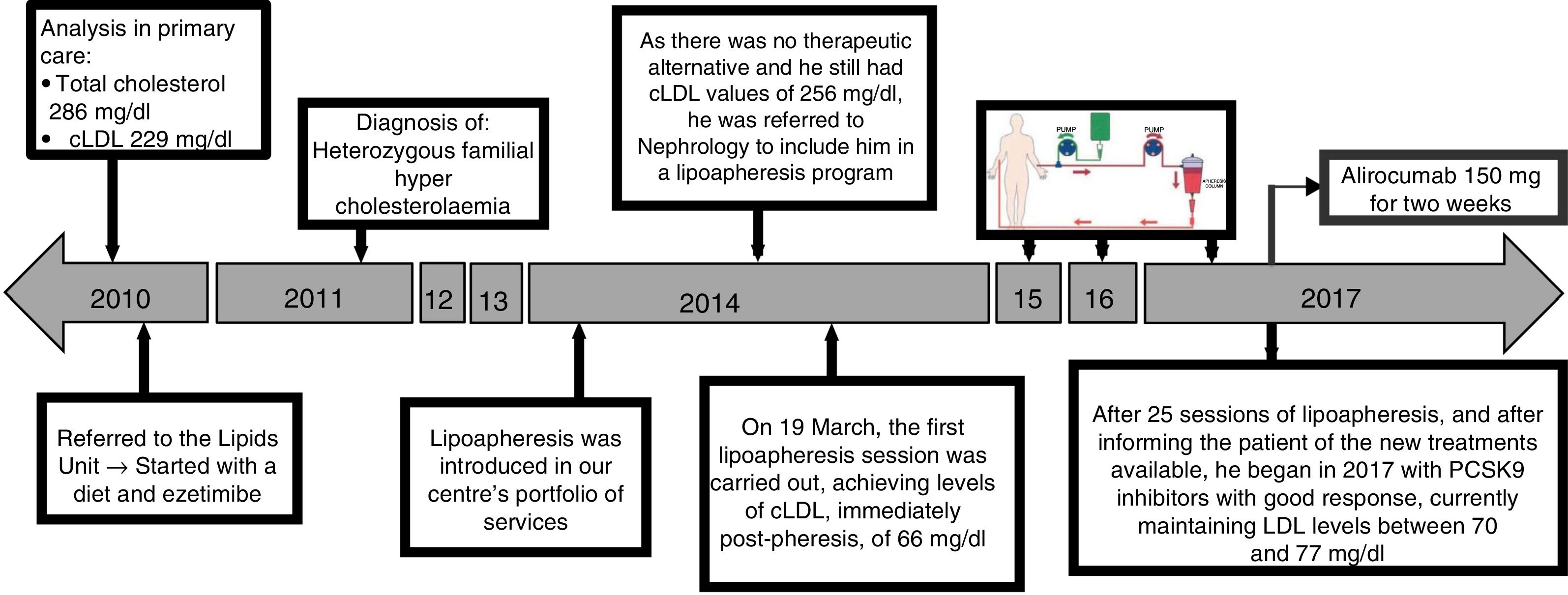

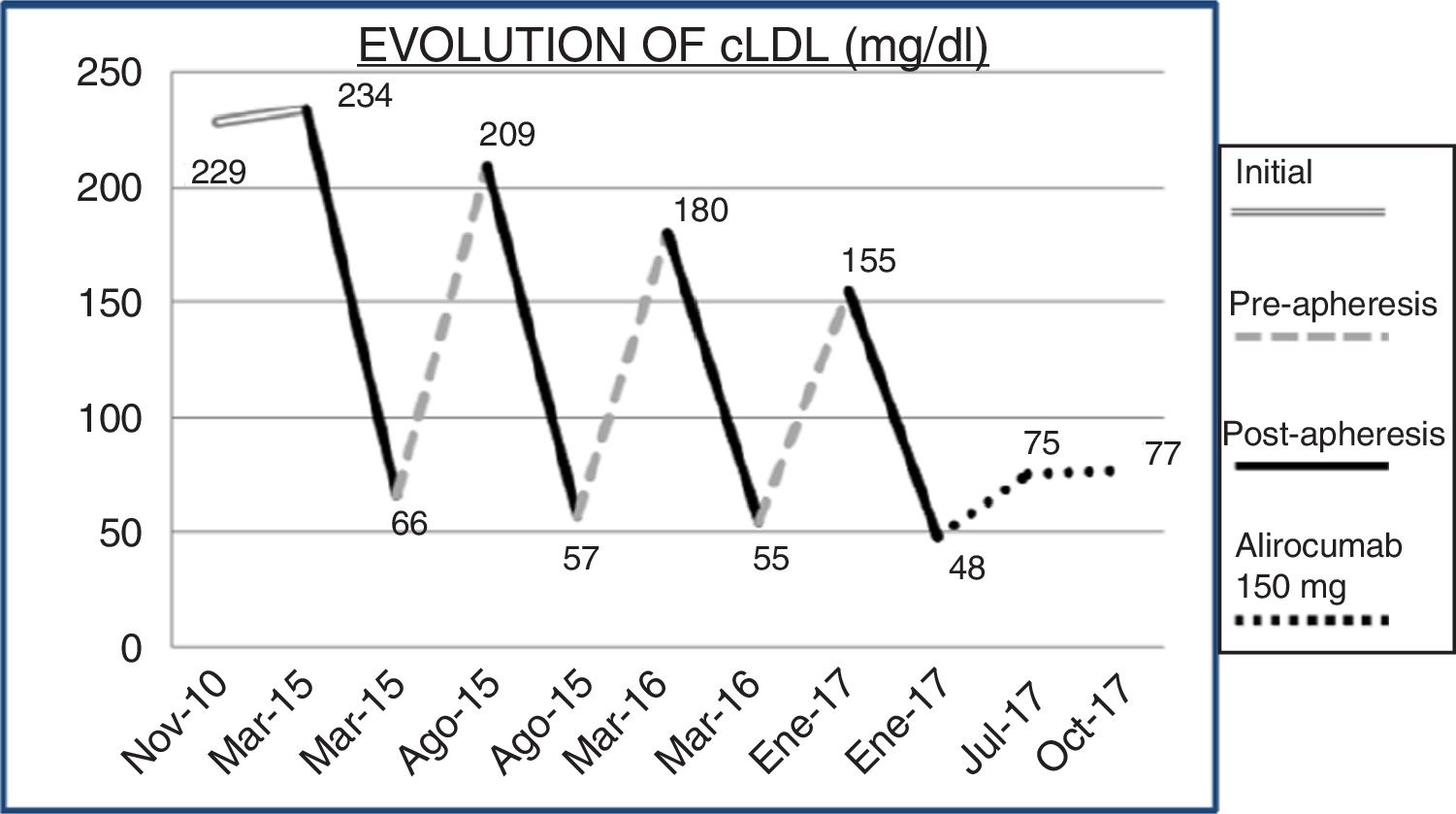

Fig. 1 shows the chronological evolution of the different treatments that the patient took. In 2014, LDL apheresis was added to the portfolio of services offered by our centre, so by continuing with figures of cLDL 256mg/dl and as there was no therapeutic alternative, he was referred to nephrology. Immediately after the first apheresis session, the cLDL was lowered to 66mg/dl. After 25 sessions of LDL apheresis, the patient was informed of the availability in our centre of PCSK9 inhibitors (iPCSK9). In the first half of 2017, treatment was started with 150mg of alirocumab, biweekly, subcutaneously, and he was able to maintain a plasma concentration of cLDL between 70 and 77mg/dl. Variations of cLDL with the different treatments are shown in Fig. 2. No adverse reactions secondary to treatment with iPCSK9 were detected. Nor was there a worsening of the muscular dystrophy of the patient in terms of the appearance of muscular symptoms, such as myalgia or weakness, nor analysis variations such as the increase in creatine kinase (CK).

DiscussionPatients with HeFH have elevated cLDL levels from birth, with the consequent premature risk of coronary heart disease. Cholesterol is deposited in the arteries accelerating the formation of atheroma plaques. The prevalence of HeFH is estimated to be one in 300 individuals in Europe and 200–250 in the USA.1

The diagnosis of HeFH is made by genetic tests or based on clinical criteria. A mutation in the genes of the LDL, apoB or PCSK9 receptor confirms this diagnosis. When genetic tests are not available, various scoring systems are used for clinical diagnosis, based on cLDL levels, presence of xanthomas or corneal arcus in the physical examination of the patient, personal history of early cardiovascular disease or history of elevated cLDL in first-degree relatives with or without premature cardiovascular disease.1

The lipid objective in HeFH is a decrease in cLDL below 70mg/dl. The reduction in cLDL levels has shown a stabilisation, or even the regression of atheroma plaque, which results in a decrease in cardiovascular events, as well as coronary heart disease mortality and overall mortality.1

In addition to hygienic-dietary modifications, the first line of pharmacological treatment is statins at the maximum tolerated dose. Most patients with FH do not reach the target levels of cLDL, which forces a second drug to be added: ezetimibe, iPCSK9 or both.1–4 If despite these measures an adequate cLDL is not achieved, LDL apheresis can be considered as a third-line therapy.1,2,5 The congenital muscular dystrophy presented in our case contraindicates the use of statins because of the risk of worsening the disease with myalgia and rhabdomyolysis. Before the introduction of iPCSK9, the only cholesterol-lowering measures available were resins, ezetimibe and LDL apheresis.

LDL apheresis is the extracorporeal elimination of lipoproteins that contain circulating apoB, including LDL, lipoprotein (a) and VLDL. There are several apheresis methods available and it is usually carried out every week or biweekly. It is currently reserved for patients with homozygous FH or for patients with HeFH who do not achieve objective levels of cLDL despite optimal pharmacological treatment.2,6 The high costs per session and the frequency of treatment represent an important barrier in the treatment of FH.6

iPCSK9s are drugs capable of reducing cLDL up to 60%, associated with statin therapy. They are well-tolerated and safe drugs, with a low adverse event rate and generally of low severity.2–5 Currently, no muscle toxicity or increased CK has been found in patients after administration of iPCSK9.7 With this new medication, it is possible to space and even avoid treatment with LDL apheresis in patients with HeFH.5,6,8

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

Please cite this article as: Arnedo Hernández S, Mosquera Lozano JD, Martínez de Narvajas Urra I, Menéndez Fernández E, Rabadán Pejenaute E, Baeza Trinidad R, et al. Tratamiento de la hipercolesterolemia familiar con iPCSK9 en un paciente diagnosticado de distrofia muscular congénita con contraindicación para la toma de estatinas. Clín Investig Arterioscler. 2019;31:278–281.