To estimate the clinical and economic benefits derived from increasing the use of fixed-dose combinations of high-intensity statins and ezetimibe in patients at high/very high cardiovascular risk, from the perspective of the Spanish National Health System (SNS).

MethodsA baseline scenario (current market shares) was compared with scenarios that increased the use of fixed-dose combinations (alternative: 30% increase; optimized: 69% increase). The potential annual increase in the number of controlled patients, cardiovascular events avoided and the associated savings in direct medical costs were estimated, including the cost of pharmacological treatment, follow-up, and managing cardiovascular events over a three-year time horizon.

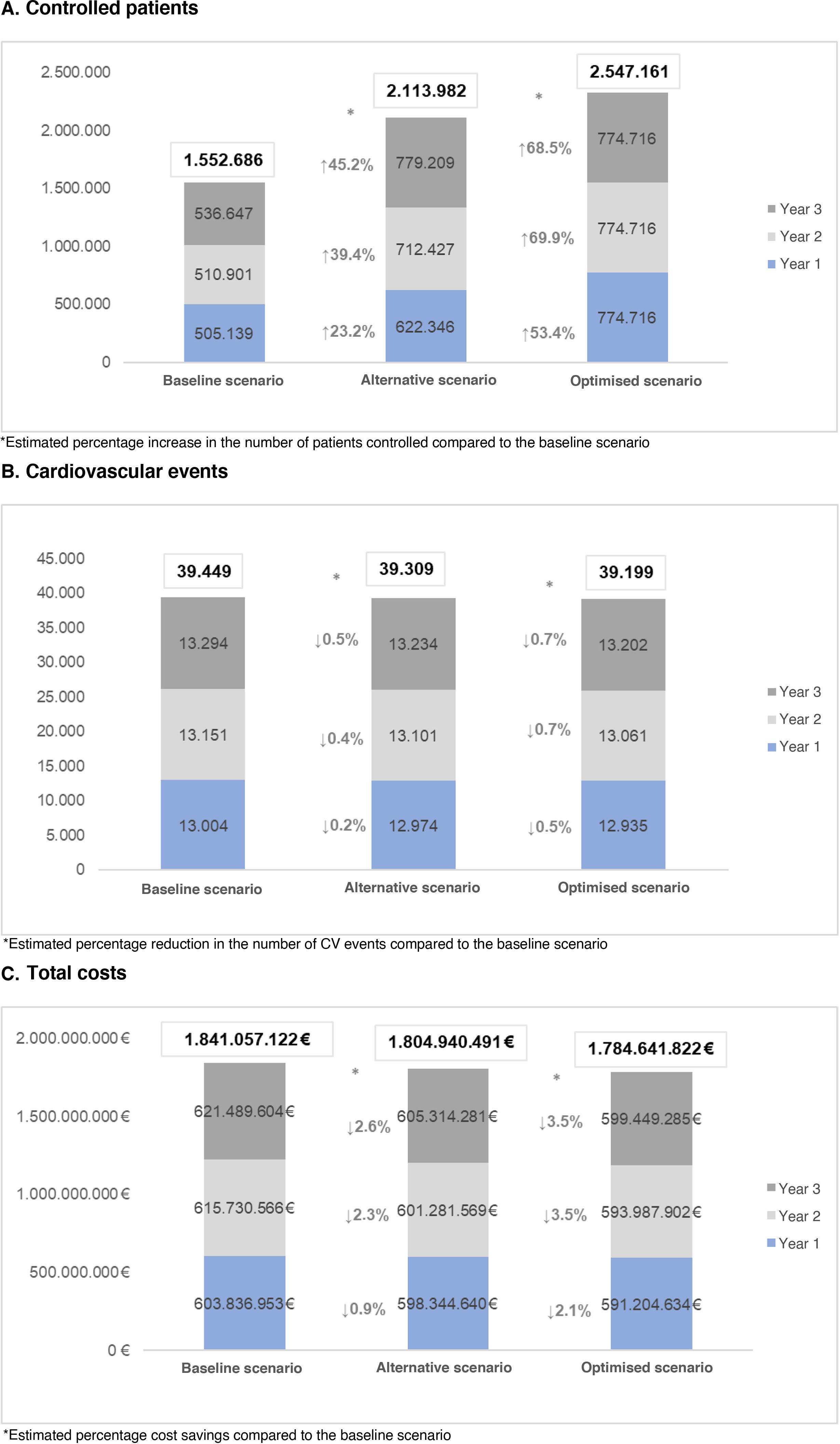

ResultsOver the three years of the study, the baseline scenario estimated a total of 1,552,686 controlled patients and 39,449 cardiovascular events, with a total cost to the NHS of €1,841,057,122. In the alternative scenario, controlled patients would increase by 36.1%, and 139 cardiovascular events would be avoided, resulting in savings for the NHS of 36,116,631 €. In the optimized scenario, there would be a 64% increase in controlled patients and 250 CV events would be avoided, leading to savings of 56,415,300 € for the NHS.

ConclusionIncreased use of high-intensity statin and ezetimibe fixed-dose combinations in patients with high/very high CV risk may increase the number of controlled patients, reduce CV events and produce economic savings from an NHS perspective.

Estimar el beneficio clínico y económico derivado del incremento del uso de combinaciones a dosis fijas de estatinas de alta intensidad y ezetimiba en el tratamiento de pacientes de alto/muy alto riesgo cardiovascular, desde la perspectiva del sistema nacional de salud (SNS) español.

MétodosSe comparó un escenario basal (cuotas actuales de mercado) frente a escenarios que incrementaban el uso de las combinaciones fijas (alternativo: incremento del 30%; optimizado: 69%). Se estimó el potencial aumento anual en el número de pacientes controlados, eventos cardiovasculares evitados y ahorro de costes directos médicos asociados incluyendo; coste del tratamiento farmacológico, de seguimiento, y manejo de los eventos cardiovasculares, a lo largo de un horizonte temporal de tres años.

ResultadosA lo largo de los tres años de estudio, en el escenario basal se estimaron un total de 1.552.686 pacientes controlados y 39.449 eventos cardiovasculares, con un coste total para el SNS de 1.841.057.122 €. En el escenario alternativo los pacientes controlados aumentarían un 36,1%, se evitarían 139 eventos cardiovasculares, con un ahorro para el SNS de 36.116.631 €. En el escenario optimizado existiría un aumento del 64% de pacientes controlados y llegarían a evitarse 250 eventos cardiovasculares, con un ahorro para el SNS de 56.415.300 €.

ConclusiónEl aumento del uso de las combinaciones de estatina de alta intensidad y ezetimiba en dosis fija en pacientes de alto y muy alto riesgo cardiovascular puede aumentar el número de pacientes controlados, reducir complicaciones cardiovasculares y producir ahorros económicos desde la perspectiva del SNS.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is associated with a high socioeconomic burden, is one of the leading causes of death in Spain, and leads to a high level of disability.1,2 It is estimated that control of the main cardiovascular risk factors would reduce CV events and thus reduce the impact of CVD by 80.0%.3

In this context, the guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS), among others, establish the reduction of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels as the main target for the prevention of CV events.4,5 Specifically, it has been estimated that a reduction of 1 mmol/L is associated with a 19% to 25%6,7 relative risk reduction of major adverse CV events (MACE). The ESC/EAS guidelines also recommend that cardiovascular risk should be assessed quantitatively using the Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE), recently updated to SCORE2, and that LDL-C reduction targets should be set on this basis.4,8

In our country, it is estimated that a significant percentage of patients with hypercholesterolaemia do not achieve their LDL-C control targets.9 A real-life study conducted in our setting shows that only 31% of patients achieve these targets, which differs from the perception of physicians, who believe that 62% of patients are controlled.9

Statins are currently the drug of choice for the treatment of hypercholesterolaemia, and their efficacy in reducing LDL-C has been demonstrated in several studies, leading to significant improvements in the risk for a CV event.7 However, these reductions are sometimes insufficient, especially in high-risk patients, for whom LDL-C reduction of more than 50.0% is the goal.4 In these cases, combined treatment with statins and ezetimibe is recommended, as the addition of ezetimibe to monotherapy with different statins has been associated with an additional reduction in LDL-C of around 20%.10

Achieving good control of LDL-C is key to preventing or delaying the onset of a CV event. In practice, however, there are barriers that make it difficult to achieve the therapeutic goal of LDL-C reduction,4 which include therapeutic inertia and poor adherence. Treatment is not intensified in a high percentage of patients with a CV event, which could be as high as 70% in our country, despite their not achieving the therapeutic goal,9,11–14 and they even remain on the same treatment after suffering a CV event.14 Similarly, several studies have identified non-adherence to statin treatment as a factor that increases CV morbidity and mortality, whereas adherent patients could reduce the risk of CV events by up to 55%.15–17 In addition, studies conclude that increasing the number of tablets/capsules in a treatment regimen negatively affects adherence,18,19 with each additional tablet/capsule in a lipid-lowering regimen potentially reducing patient adherence by 10%,20 thereby increasing the risk of CV complications.

The use of a fixed-dose combination lipid-lowering therapy (statin/ezetimibe) could lead to better outcomes in the control of hypercholesterolaemia, not only by saving on drug costs, but also by improving adherence, compared with free doses. Thus, its use could reduce the risk for CV events, which would reduce the socioeconomic burden of the disease.

Therefore, the main objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of fixed-dose combinations of high-intensity statins and ezetimibe in the treatment of hypercholesterolaemia in patients at high or very high risk for a CV event, from the perspective of the Spanish National Health System (SNS).

MethodsWe conducted an analysis using an analytical model developed in Microsoft Excel to evaluate the clinical and economic benefits of increasing the use of fixed-dose combinations of high-intensity statins and ezetimibe for the treatment of hypercholesterolaemia. By comparing different scenarios (in which the use of fixed doses varies in different proportions over time), the potential annual increase in the number of patients controlled, the number of CV events prevented, and the cost savings over a 3-year period were estimated. The parameters and assumptions used to develop the analysis were validated by a multidisciplinary panel of experts in cardiovascular disease management (primary care, cardiology, internal medicine) and a patient safety specialist.

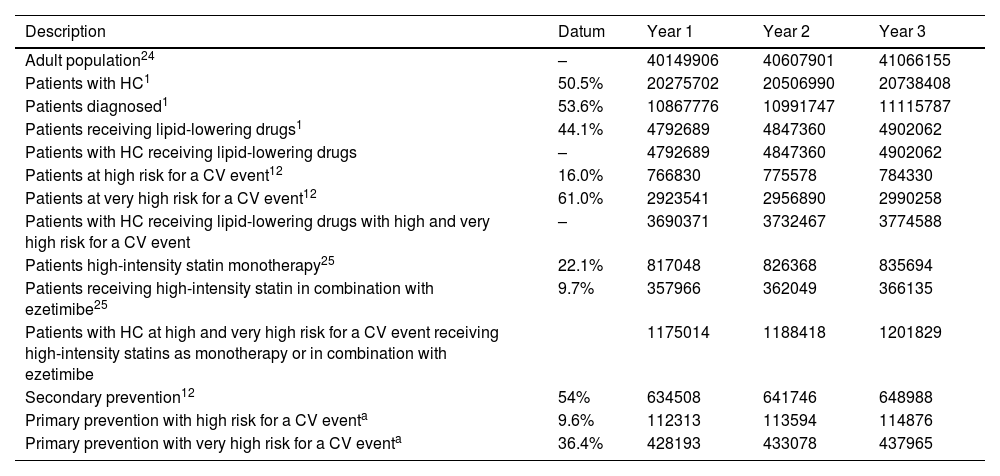

PopulationThe number of patients with hypercholesterolaemia receiving lipid-lowering medication was estimated from the adult Spanish population in each year of the study.21,22 Only patients at high and very high risk for a CV event9 treated with high-intensity statins alone or in combination with ezetimibe were considered as the target population.23

The target population was then divided into subgroups, taking into account that 54% of this population were secondary prevention patients,9 and the remainder were primary prevention patients (46.0%), the latter subdivided into patients at high risk for a CV event (9.6%) and at very high risk for a CV event (36.4%)9 (Table 1).

Estimation of the population included in the analysis.

| Description | Datum | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult population24 | – | 40149906 | 40607901 | 41066155 |

| Patients with HC1 | 50.5% | 20275702 | 20506990 | 20738408 |

| Patients diagnosed1 | 53.6% | 10867776 | 10991747 | 11115787 |

| Patients receiving lipid-lowering drugs1 | 44.1% | 4792689 | 4847360 | 4902062 |

| Patients with HC receiving lipid-lowering drugs | – | 4792689 | 4847360 | 4902062 |

| Patients at high risk for a CV event12 | 16.0% | 766830 | 775578 | 784330 |

| Patients at very high risk for a CV event12 | 61.0% | 2923541 | 2956890 | 2990258 |

| Patients with HC receiving lipid-lowering drugs with high and very high risk for a CV event | – | 3690371 | 3732467 | 3774588 |

| Patients high-intensity statin monotherapy25 | 22.1% | 817048 | 826368 | 835694 |

| Patients receiving high-intensity statin in combination with ezetimibe25 | 9.7% | 357966 | 362049 | 366135 |

| Patients with HC at high and very high risk for a CV event receiving high-intensity statins as monotherapy or in combination with ezetimibe | 1175014 | 1188418 | 1201829 | |

| Secondary prevention12 | 54% | 634508 | 641746 | 648988 |

| Primary prevention with high risk for a CV eventa | 9.6% | 112313 | 113594 | 114876 |

| Primary prevention with very high risk for a CV eventa | 36.4% | 428193 | 433078 | 437965 |

CV: cardiovascular; HC: hypercholesterolaemia.

To distribute 46.0% of primary prevention patients, the percentages of patients at high and very high risk presented above are used (16.0% and 61.0%).12

Based on the information contained in the ESC/EAS guidelines4 and the recommendations of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (SEC),24 the percentage risk for a CV event and baseline LDL-C levels were assigned to patients, together with their control targets. Different profiles were defined for patients at high CV risk in primary prevention (SCORE risk: 7.5%; LDL-C: 160 mg/dl; targets: 50.0% reduction in LDL-C and ≤70 mg/dl), very high CV risk primary prevention (SCORE risk: 11.0%; LDL-C: 130 mg/dl; targets: 50.0% reduction in LDL-C and ≤55 mg/dl) and secondary prevention (SCORE risk: 12.5%; LDL-C: 130 mg/dl; targets: 50.0% reduction in LDL-C and ≤55 mg/dl). The suitability of the parameters considered for each subgroup for real-world clinical practice was validated by the expert panel.

ScenariosTo capture the benefit of increased use of fixed-dose combinations of high intensity statins and ezetimibe, a baseline scenario was compared with two comparative scenarios, which we will refer to as the alternative scenario and the optimised scenario.

The baseline scenario reflects the current use of treatment for hypercholesterolaemia in patients at high and very high risk for a CV event. In year 1 of the analysis, patients were allocated to each of the alternatives considered based on their national market share.25 It was assumed that 5% of patients receiving high intensity statins as monotherapy in year 1 would switch to combination therapy with ezetimibe in individual doses in year 2 of the analysis and then to fixed doses in year 3 of the analysis (Table 2).

Usage quotas used to distribute patients across the different scenarios.

| Treatment | Baseline scenario | Alternative scenario | Optimised scenario | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

| Rosuvastatin 10 mg + ezetimibe | .2% | .2% | .2% | .2% | .2% | .2% | .2% | .2% | .2% |

| Rosuvastatin 20 mg + ezetimibe | .7% | 1.7% | 1.7% | .7% | .7% | .7% | .7% | .7% | .7% |

| Atorvastatin 40 mg + ezetimibe | .5% | .5% | .5% | .5% | .5% | .5% | .5% | .5% | .5% |

| Atorvastatin 80 mg + ezetimibe | .6% | 1.2% | 1.2% | .6% | .6% | .6% | .6% | .6% | .6% |

| Rosuvastatin 10 mg/ezetimibe | 21.8% | 21.8% | 21.8% | 21.8% | 21.8% | 21.8% | 21.8% | 21.8% | 21.8% |

| Rosuvastatin 20 mg/ezetimibe | 27.7% | 27.7% | 28.7% | 33.8% | 38.0% | 41.0% | 41.7% | 46.1% | 47.4% |

| Atorvastatin 40 mg/ezetimibe | 10.2% | 10.2% | 10.2% | 10.2% | 10.2% | 10.2% | 10.2% | 10.2% | 10.2% |

| Atorvastatin 80 mg/ezetimibe | 5.2% | 5.2% | 5.8% | 9.0% | 11.7% | 13.6% | 14.1% | 16.8% | 17.7% |

| Rosuvastatin 20 mg | 20.3% | 19.3% | 18.3% | 14.2% | 10.0% | 7.0% | 6.3% | 2.0% | .6% |

| Atorvastatin 80 mg | 12.9% | 12.3% | 11.7% | 9.0% | 6.3% | 4.4% | 4.0% | 1.2% | .4% |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

In both the alternative and the optimised scenario, a more dynamic increase in the percentage of fixed-dose statin/ezetimibe combinations was considered, starting in the first year of the analysis, after control had been achieved with statin and ezetimibe monotherapy. In the alternative scenario, this percentage was set at 30.0% (the percentage of patients not controlled with statin monotherapy as defined in clinical practice guidelines)4,26 and 69.0% in the optimised scenario (based on a study that determined the percentage of Spanish patients not controlled in real life)9 (Table 2).

Clinical benefit parametersFor each scenario, the number of patients controlled, and the number of CV events were determined using the efficacy of each treatment (percentage reduction in LDL-C).27 The same efficacy was assumed for fixed doses (statin/ezetimibe) and single doses (statin + ezetimibe). Adherence was also taken into account, based on the number of tablets taken (79% for fixed-doses/monotherapy; 69% for single-doses)20 to adjust reductions in LDL-C.

The adherence-adjusted LDL-C reduction percentage was applied to the baseline LDL-C values of each subgroup to determine their LDL-C reduction. This reduction was used to determine the annual risk of CV events, because for every 1 mol/dl reduction in LDL-C, the annual reduction in CV event risk was estimated to be 6.9% in primary prevention patients and 4.6% in secondary prevention patients (see Table 3 for details).

Estimated treatment efficacy.

| Efficacy of interventions29,a | Reduction in LDL-C (%) |

|---|---|

| Rosuvastatin 10 mg + ezetimibe | 58.3% |

| Rosuvastatin 20 mg + ezetimibe | 63.4% |

| Atorvastatin 40 mg + ezetimibe | 64.0% |

| Atorvastatin 80 mg + ezetimibe | 68.4% |

| Rosuvastatin 10 mg/ezetimibe | 58.3% |

| Rosuvastatin 20 mg/ezetimibe | 63.4% |

| Atorvastatin 40 mg/ezetimibe | 64.0% |

| Atorvastatin 80 mg/ ezetimibe | 68.4% |

| Rosuvastatin 20 mg | 50.9% |

| Atorvastatin 80 mg | 51.8% |

| Adherence23 | Probability of being adherent |

| Fixed-doses/monotherapy | 79.0% |

| Single-doses | 69.0% |

| Reduction in risk for a CV event at 5 years4,b | Probabilityc |

| Primary prevention | 30.0% |

| Secondary prevention | 21.0% |

CV: cardiovascular; LDL-C: low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol.

In addition, the adherence-adjusted reduction in LDL-C allowed us to determine the percentage of patients achieving control targets as recommended in the guidelines.4,24

Economic parametersDirect medical costs were estimated, including the cost of drug treatment, the cost of patient follow-up (visits and tests), and the cost of managing CV events.

The annual drug cost for each treatment option was estimated based on the PVL published in the official database of the Spanish College of Pharmacists, Bot Plus Web.28 For fixed-dose regimens, the average of the different presentations was used, whereas for single-dose regimens, the reference price of ezetimibe was added to that of the statin (Appendix B Table A1).

The cost of patient follow-up was estimated based on whether or not the patient was controlled (achieving the control targets set for the patient subgroup), taking into account differences in resource use. The annual frequency of visits and tests in each scenario was estimated by the expert panel based on their clinical experience, considering 1.5 primary care physician visits per year for controlled patients and 4 for uncontrolled patients, and 1.5 and 3.5 blood tests, respectively.

A total cost per CV event was estimated (€6692.37). This was obtained by weighting the unit cost of each event considered and its frequency according to Spanish data from the National Statistics Institute (INE)29 (acute myocardial infarction: 33.3%; angina pectoris: 5.9%; cerebrovascular event: 60.80%).

The unit costs of the visits, tests, and events considered were extracted as the average of the rates available in the eSalud30 medical cost database (€, 2023) and are presented in Appendix B Table A1.

AnalysisIn this analysis, the number of patients monitored, the number of CV events and the total costs (drug costs, follow-up costs, and CV event management costs) were estimated annually and cumulatively for the three years of the study in each scenario. The results of the alternative scenario and the optimised scenario were compared with those of the baseline scenario on an annual and cumulative basis.

ResultsControlled patientsIn the baseline scenario, a total of 1552.686 patients were estimated to be controlled over the three years of the study. In the alternative scenario, the number of patients controlled was 2113.982, representing a 36.1% increase in the number of patients controlled over the time horizon compared to the baseline scenario.

In the optimised scenario, a total of 2547.161 patients were estimated to be controlled over 3 years, representing a 64.0% increase in the number of patients controlled over the time horizon compared to the baseline scenario (Fig. 1A).

Number of CV eventsIn the baseline scenario, 39449 CV events were estimated over the three years of the study, while in the alternative scenario, a total of 39309 CV events were estimated, thus avoiding 139 CV events and assuming a reduction of .4% compared to the baseline scenario.

In the optimised scenario, 39199 CV events were estimated over the three years of the study, thus avoiding 250 CV events compared to the baseline scenario, representing a reduction of .6% (Fig. 1B).

Total costThe total cost of the baseline scenario amounted to €1841057122 over the three years of the study, while in the alternative scenario the total cost amounted to €1804940491, representing a saving of 2.0% in total cost compared to the baseline scenario.

In the optimised scenario, the total cost was estimated at €1784641822 over the three years of the study, representing a saving of 3.1% in the estimated total cost compared to the baseline scenario (Fig. 1C).

In general, both in the alternative scenario and in the optimised scenario, an increase in drug cost was observed compared to the baseline scenario, due to the increase in the number of patients receiving combination therapy. However, this increase in cost was offset by the savings generated by the increase in the number of patients controlled (lower follow-up costs) and the number of CV events avoided (lower costs per CV event). In this regard, the greatest savings would come from the cost of patient follow-up, which shows a difference of 13.3% compared to the alternative scenario and 23.7% compared to the optimised scenario over the three years of the study (Table 4).

Disaggregated results of the total cost for each scenario at one year and difference from the baseline scenario.

| Drug cost | Baseline scenario | Alternative scenario | Difference (%)a | Optimised scenario | Difference (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | €288659667 | €302572323 | 4.8% | €320658775 | 11.1% |

| Year 2 | €296971969 | €315873761 | 6.4% | €334349455 | 12.6% |

| Year 3 | €302441131 | €326411117 | 7.9% | €341267823 | 12.8% |

| Cost of follow-up | |||||

| Year 1 | €228147648 | €208943174 | –8.4% | €183977357€ | –19.4% |

| Year 2 | €230750161 | €197730139 | –14.3% | €172227028 | –25.4% |

| Year 3 | €230080349 | €190336551 | –17.3% | €169828947 | –26.2% |

| Cost of CV events | |||||

| Year 1 | €87029637 | €86829144 | –.2% | €86568502 | –.5% |

| Year 2 | €88008436 | €87677670 | –.4% | €87411418 | –.7% |

| Year 3 | €88968124 | €88566613 | –.5% | €88352515 | –.7% |

The aim of this study was to estimate the effectiveness of fixed-dose combinations of high-intensity statins and ezetimibe in the treatment of hypercholesterolaemia. This is a theoretical exercise, developed in collaboration with experts based on sources from the literature, which estimates the clinical and economic consequences of increasing the use of intensive lipid-lowering treatment through the combined use of statins and ezetimibe according to control of LDL-C levels.

The results show that an increase in the proportion of patients receiving fixed doses of high-intensity statins and ezetimibe could increase the proportion of patients controlled, resulting in a reduction in CV events and overall cost savings to the NHS. Specifically, the alternative scenario would result in a 36.1% increase in the number of patients controlled, prevent 139 CV events (–.4% vs. the baseline scenario), and save €36 million over the three years of analysis. In the optimised scenario, the number of patients controlled would increase by 64.0%, 250 CV events would be prevented (–.6% vs. baseline scenario), and savings of more than €56 million would be achieved over the three years of analysis. These savings could increase when considering the impending loss of exclusivity for these fixed-dose combinations of high-dose statins and ezetimibe, coupled with potential generic entry and price erosion. A sensitivity analysis in the optimised scenario - considering a 40% reduction in the price of fixed-dose combinations - shows a reduction in drug costs, which could result in savings of around €180 million over three years. All these analyses support the effectiveness of interventions aimed at increasing the use of fixed-dose combinations of statin/ezetimibe vs. individual doses.

On the other hand, lack of patient adherence due to the complexity of the treatment or the high number of ‘tablets’ can make it difficult to achieve therapeutic goals. Previous studies have shown that fixed-dose combinations improve adherence both in patients with hypercholesterolaemia (patients treated with a one-tablet combination are 87% more likely to be highly adherent than those prescribed a two-tablet combination),17 and in other diseases.31,32 In cardiovascular prevention, previous studies have shown better results in terms of adherence, incidence of CV events, and mortality, as well as savings in healthcare costs, in patients with hypertension treated with fixed combinations of different therapies compared with administration of single doses.33 There are other reasons for poor adherence, including factors related to the healthcare system or team (lack of patient-specific information, lack of time to communicate with the patient, monitoring of treatments and the patient), which have been previously reported in the literature.34

Similarly, another cause identified in the literature that hinders the achievement of therapeutic goals is therapeutic inertia, with a clear deficit in the intensification of treatment in patients who do not achieve control goals with the therapy received. In Spain, a study estimated that therapeutic inertia (considered high in 29.5% of cases and very high in 28.9%) occurred in 42.8% of medical visits in patients with dyslipidaemia and ischaemic heart disease who met the criteria for a change in treatment.13 A major factor contributing to this therapeutic inertia is an overestimation of the degree of control of hypercholesterolaemia9,35 and/or an underestimation of the vascular risk of patients by their physicians.35 Real-world studies show that these percentages are high,9,11,36,37 resulting in markedly poor control of lipid-lowering treatment in patients at high CV risk. This can have negative consequences for patients: increased risk of CV events, reduced quality of life and increased use of healthcare resources. Although Spain appears to be one of the European countries with the highest use of combination therapy, there is still a clear deficit in control,25 and it is important to note that significant interregional differences were observed in the achievement of LDL-C targets and the use of lipid-lowering therapies. These regional differences suggest that differences in access to and use of healthcare systems, together with the health status of the population, make place of residence an additional determinant.38

Our study is not without its limitations. First, our analysis is based on a comparison of hypothetical scenarios. However, these were constructed on the basis of the literature and validated by experts, with the aim of highlighting the increase in the use of fixed doses by constructing a conservative baseline scenario in which therapy is intensified in only 5% of patients who are not controlled, and ezetimibe is added as a single dose; an alternative scenario, in line with clinical practice guidelines, in which fixed-dose therapy is intensified in 30% of patients; and an optimised scenario, which aims to demonstrate the results of intensifying therapy in all patients who do not achieve control targets according to the literature, taking into account this fixed-dose intensification. It should be noted that there are a number of patients who do not achieve therapeutic targets despite an improvement in their lipid profile. Assessing the costs and benefits of additional lipid-lowering treatments (especially PCSK9 inhibitors) is beyond the scope of this analysis and requires further study. On the other hand, the estimate of vascular risk used as a reference is based on the SCORE scale, which is based on mortality estimates, not morbidity estimates. We do not have updated data on the degree of control of dyslipidaemia based on the updated SCORE2 and SCORE-OP scales, which could change our estimates. However, SCORE and SCORE-226 use the same risk factors, and therefore the results should be similar, at least qualitatively. Thirdly, our study does not assess the quality-of-life benefits, or the potential societal benefits associated with the reduction of cardiovascular complications, healthcare costs, and maintenance in patients who remain active. It is reasonable to assume that the total societal benefit may be much greater than estimated in terms of SNS costs.

Among the strengths of our study, we can mention that our analysis evaluates not only the economic consequences of increasing the use of fixed doses, but also the potential clinical consequences (in terms of percentage of patients controlled, reduction in CV events). Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the use of fixed doses versus single doses and their clinical and economic impact in Spain. Finally, it should be noted that our baseline scenario is based on real-world prescribing, which means that our results would be plausible if the improvements proposed in the alternative scenario and the optimised scenario were implemented in our setting.

ConclusionsIncreased use of high-intensity fixed-dose combinations of statins and ezetimibe in patients at high and very high vascular risk may increase the number of patients controlled, reduce cardiovascular complications, and generate economic savings from the perspective of the SNS. These results may support the efficacy of fixed-dose combinations of high-intensity statins and ezetimibe in the treatment of hypercholesterolaemia in patients at high or very high risk for a CV event.

Carlos Guijarro reports that he has received remuneration from Amarin, Amgen, Ferrer, Daiichi Sankyo, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Sanofi, and Servier for lectures and consultancy. Angel Diaz and Eva Moreno have received consultancy fees from Servier. Paula Gamonal is an employee of Servier Spain. Maria Soler and Neus Vidal-Vilar are paid consultants to Outcomes'10, an evidence generation company funded by Servier to develop this analysis. Rosa Fernández declares that she has received remuneration from Servier, Novartis, Amgen, Sanofi, AstraZeneca, and Daiichi Sankyo for lectures and consultancy services.