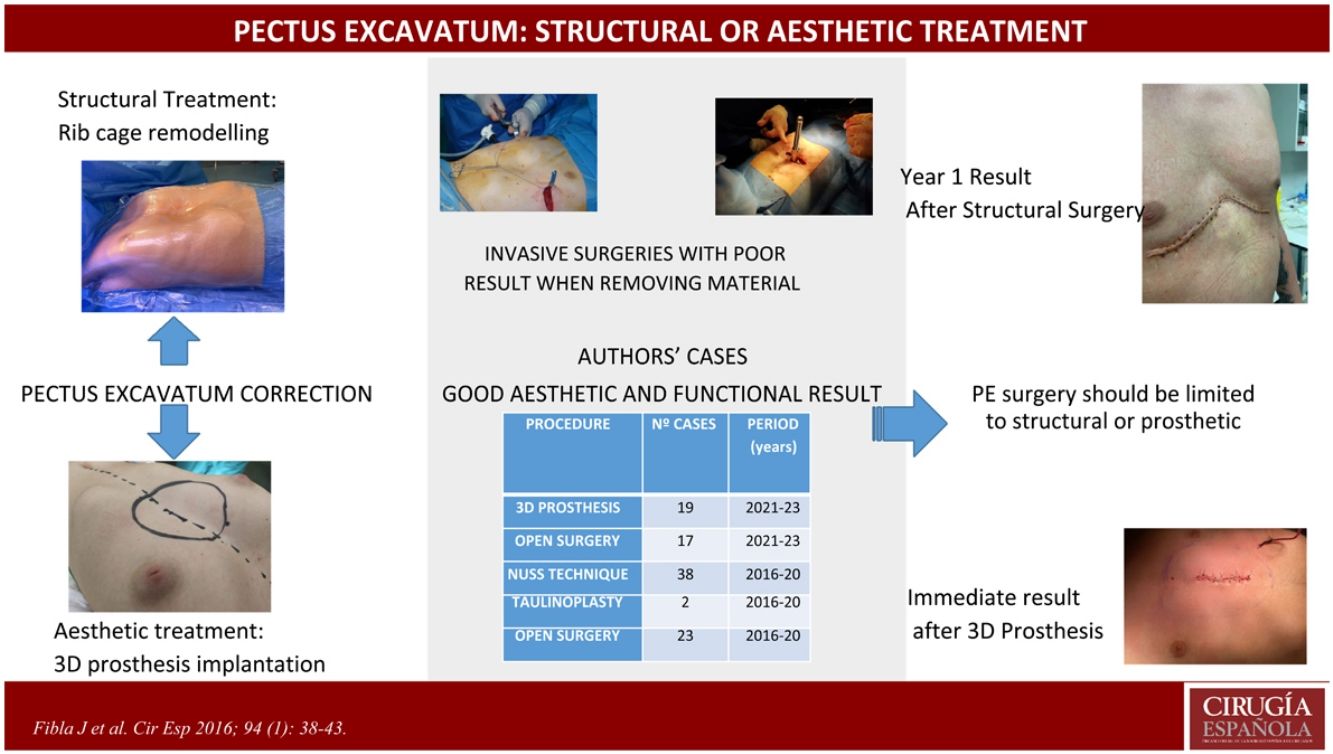

Pectus excavatum is a wall deformity that often warrants medical evaluation. In most cases, it’s a purely visual aesthetic alteration, while in others, it comes with symptoms. Several surgical techniques have been described, but their outcomes are difficult to assess due to the heterogeneity of presentations and the lack of long-term follow-up. We present our experience as thoracic surgeons, assessing correction as either structural (remodeling of the thoracic cage through open surgery) or aesthetic (design and implantation of a customized 3D prosthesis).

Material and methodsRetrospective observational study of the indication for surgical treatment of pectus excavatum carried out by a team of thoracic surgeons and the short- to mid-term results.

ResultsBetween 2021 and 2023, we treated 36 cases surgically, either through thoracic cage remodeling techniques or with 3D prostheses. There were few minor complications, and the short- to mid-term results were positive: alleviation of symptoms or compression of structures when present, or aesthetic correction of the defect in other cases.

ConclusionsSurgery for pectus excavatum should be evaluated for structural correction of the wall or aesthetics. In the former, thoracic cage remodeling requiring cartilage excision and possibly osteotomies is necessary. In the latter, the defect is corrected with a customized 3D prosthesis.

El pectus excavatum es una deformidad de pared que muchas veces reclama una valoración médica. En la mayoría de los casos es una alteración estética meramente visual y en otros se acompaña de síntomas. Se han descrito una serie de técnicas quirúrgicas, con resultados poco valorables por la heterogeneidad de la presentación y la ausencia de seguimiento a largo plazo. Presentamos nuestra experiencia como cirujanos de tórax en la valoración quirúrgica del pectus excavatum con un enfoque bien estructural (remodelación de la caja torácica mediante cirugía abierta) o estético (diseño e implantación de una prótesis personalizada 3 D).

Material y métodosEstudio observacional retrospectivo de la indicación de tratamiento quirúrgico del pectus excavatum llevado a cabo por un equipo de cirujanos torácicos y los resultados a corto y medio plazo.

ResultadosEntre 2021 y 2023 hemos tratado mediante cirugía 36 casos, bien con técnica de remodelación estructural de la caja torácica o con prótesis estética tridimensional. Hubo escasas complicaciones menores y los resultados a corto y medio plazo fueron buenos: corrección de síntomas o compresión de estructuras cuando existían o corrección estética del defecto en los otros casos.

ConclusionesLa cirugía del pectus excavatum debe evaluarse como corrección estructural de la pared o estética. En el primer caso debe hacerse remodelación de la caja torácica que exigirá exéresis de cartílago y quizás osteotomías. En el segundo se corrige el defecto con una prótesis 3 D a medida.

Congenital deformities of the chest wall encompass a broad spectrum of pathologies that present some change in the development and/or morphology of the rib cage. Some of these are minor and have only aesthetic repercussions while there are also very complex ones that can cause even the death of the patient.1

The two most common deformities are pectus excavatum (PE) and pectus carinatum (PC). Both are due to the elongation or deformity of the hyaline cartilage in the costal head area, which may or may not be associated with asymmetry and sternal angulation or rotation.2 This causes abnormal growth of the chest wall with changes in its diameters and morphology. In turn, this gives rise to variable degrees of compensatory scoliosis that can eventually produce a twofold problem to a greater or lesser extent< in the chest wall and in the spine.3

The main component of sternal chondromal cartilage is type II collagen. The composition and metabolism of this type II collagen therefore plays an important role in the aetiology and pathogenesis of some chest wall deformities, especially in the case of PE.4–6

PE is seen in 1 in 350 live births. It predominates in males, with a ratio of 3–4:1 and is uncommon in blacks. Familial incidence of 40% was found, while 30% of these cases are associated with different syndromes or diseases.

Although this may be asymptomatic, exertion-related palpitations may be found in childhood and, if the deformity is moderate or severe, it may present with dyspnoea on exertion. Some patients report pain in the anterior wall of the chest, which is due to cartilaginous hypergrowth. The condition can also cause heart problems.2

The degree of mental repercussions varies in each patient but most of them agree over having a poor aesthetic image of themselves (symptoms classified as psychological effects) caused by the deformity of the wall.7 However, there is a number of studies8,9 that have shown a positive effect after correction, with integration into social activities and disappearance of negative experiences such as frustration and sadness.

Treatment should be dynamic and may vary throughout growth. Hence the importance of being assessed at an early age and by the same team that sets down the treatment guidelines and the ideal time of application.

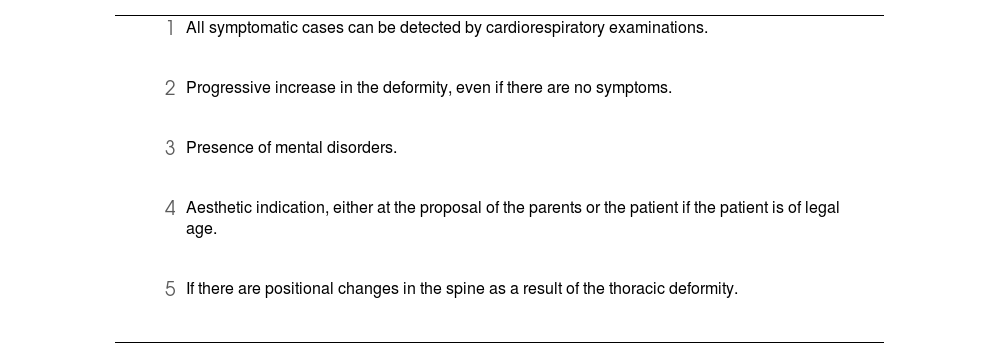

Currently, there are orthopaedic and/or surgical treatments10 (Table 1) for its correction. Surgical treatment includes the Nuss technique, taulinoplasty, Ravitch’s open surgery (and all its modifications) or the fitting of 3D prostheses with differing and poorly defined indications in each case. Our proposal was to simplify the surgical choice between operating to remodel the rib cage by open surgery (Fig. 1) or surgery that covers the defect with a 3D prosthesis designed for each case (Fig. 2).

Accepted indications for surgical correction of PE.

|

|

|

|

|

We ran a retrospective observational study among subjects who came in for congenital chest wall deformity, to be evaluated by our team of thoracic surgeons at 2 hospitals in the same city. The patients collected were assessed and treated between January 2021 and December 2023.

During this period, we evaluated 116 patients with congenital deformities of the chest wall, of whom 59 were classified as PE, with a mean age of 16.4 years. Of these, 19 continue under clinical follow-up, 4 are being treated with vacuum bell suction cups, 17 were corrected with open surgery and wall remodelling (structural surgery) and 19 with 3D prosthesis (cosmetic surgery).

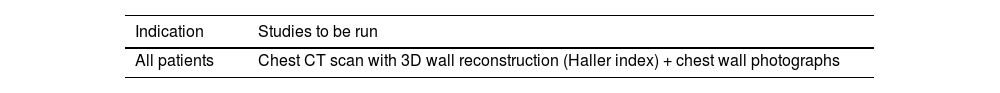

We used the suction cup in young children (in our series between 2–7 years old) as a bridge treatment for rib cage reshaping surgery, which we have practiced from the age of 9. Patients who underwent structural surgery did so due to the presence of symptoms related to the deformity. The preoperative assessment is detailed in Table 2. The technique used was that of Ravitch and its many variants, since each case requires individual planning. Most of these cases were stabilised with a retrosternal Nuss bar after cartilage excision (at different levels depending on requirements). In cases treated with 3D three-dimensional prosthesis (Sebbin® Boissy l’Aillerie, France), the design was planned based on a CT scan of the chest wall.

PE diagnostic algorithm.

| Indication | Studies to be run |

|---|---|

| All patients | Chest CT scan with 3D wall reconstruction (Haller index) + chest wall photographs |

| In the presence of symptoms | Tests to be run |

|---|---|

| Shortness of breath | Respiratory Function Tests |

| Palpitation, syncope or pre-syncope | ECG, Doppler echocardiogram |

| Psychological disturbance | Assessment by psychologist |

| Suspicion of Marfan syndrome | Thoracic CT scan, transoesophageal echocardiogram, ophthalmological examination, genetic counselling |

Not applicable.

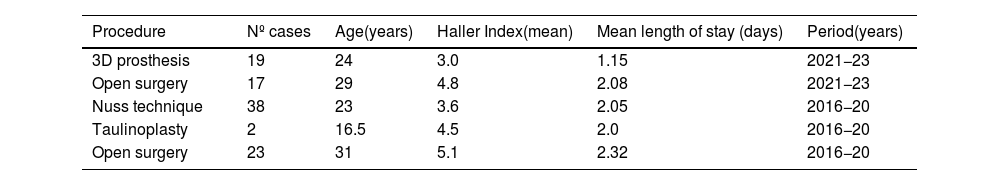

ResultsTable 3 shows the comparison of mean age with the Haller index, between the different procedures that the authors have practiced. No patients were admitted to the Intensive Care Unit. Patients referred with the classic Nuss technique11 (using video thoracoscopy) and taulinoplasty12 were those gathered over the period between 2016 and 2020: as of 2021 we have not practiced any of these techniques.

Haller’s index ratio, mean age of patients and days of admission depending on procedure.

| Procedure | Nº cases | Age(years) | Haller Index(mean) | Mean length of stay (days) | Period(years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D prosthesis | 19 | 24 | 3.0 | 1.15 | 2021−23 |

| Open surgery | 17 | 29 | 4.8 | 2.08 | 2021−23 |

| Nuss technique | 38 | 23 | 3.6 | 2.05 | 2016−20 |

| Taulinoplasty | 2 | 16.5 | 4.5 | 2.0 | 2016−20 |

| Open surgery | 23 | 31 | 5.1 | 2.32 | 2016−20 |

Regarding the complications over the study period, these occurred in 2 cases with prostheses: 1 patient with accumulation of fluid between the prosthesis and the chest wall that required surgical drainage, and one case of extrusion of the prosthesis in a woman who had undergone breast prosthesis replacement in a multiple procedure. In the case of open surgery, one case had complications of pain with repercussions on daily activity for 2 weeks.

DiscussionPE is the most common congenital deformity of the thorax, however only in some cases is it associated with cardiorespiratory compromise, which generally only becomes evident in exercise situations. Nonetheless, the percentage of cases with psychological repercussions (personality development and self-esteem) is considerable. In both situations, when the deformity is corrected, there is an improvement in physical and/or psychological symptoms.13

The most well-known procedures for its correction involve orthopaedic or surgical treatments, although these are usually combined depending on the time of evolution. Early referral to a chest wall specialist enables early evaluation and periodic follow-up to assess the need for treatment and type.

As regards age, we prefer to talk of the best age to start correction, as this is not usually a one-off, isolated process. We agree with the rest of the authors in saying that the younger the age, the more malleable the thorax is and it therefore enables us to remodel it with less aggressiveness. As in the case of Varela,13 we advocate early referral to a chest wall specialist, which enables early evaluation and periodic follow-up. This is necessary for the assessment of different treatments, depending on the stage, since the deformity and the possibilities of correction change with growth. In the most pronounced cases, or those with symptoms, we start with cupping in children under the age of 10. This has enabled us to delay open surgery until that age in the most severe cases, avoiding multiple rod replacement with growth.14 We are of the opinion that in accentuated cases, visible from an early age and/or with symptoms, open surgery should be performed to reshape the wall.

The different series agree that the surgical indication is usually aesthetic in most cases.15 Several surgical techniques have been described throughout history. From the time Sauerbruch described the extensive resection of cartilage in 191316 and laid the foundation for chest wall remodelling surgery, up to Nuss describing the technique that avoided the resection of cartilage and sternal section, multiple techniques have been published. It is difficult to evaluate the results as the series are very heterogeneous and tinged with subjectivity, and the result after the removal of the bar is ignored in these studies. However, it is clear that both techniques established a clear distinction: whether or not to perform chondrectomies and/or osteotomies.

We agree that a Haller index greater than 3.25 correlates with severe deformities that typically require structural correction,13 but not always. The joint evaluation of age, symptoms, psychological impact and the value of the Haller index should lead us to making the best decision as regards the type of surgery: either structural or aesthetic.

In the case of absence of symptoms and/or signs of compression or significant psychological repercussions, we performed the surgery between the ages of 15 and 18 depending on body development. At the present time, we opt for open surgery if there are symptoms or visceral changes that can be observed. The Haller index, on its own, is considered decisive if it is higher than 4.5 and the patient is under 25 years of age. After that age, and if the patient has been living a normal life, we recommend the prosthesis.

Nuss’s so-called minimally invasive technique gave a boost to treatment, especially for paediatric surgeons. However, we consider that the passage of a retrosternal bar using video surgery, with obligatory passage across the mediastinum, should not be minimised or performed by non-expert hands, due to potential complications and more so in children/adolescents with a benign pathology. In addition, it is important to remember that the simple placement of a bar (or screw in taulinoplasty) without modifying the permanent bone-cartilaginous structures will produce changes that are not obvious when removing the osteosynthesis material that supports them.

This, together with studies comparing the Nuss technique with the Ravitch technique17,18 that conclude a greater number of complications (reaching 35% compared to 14%) in the former case, in addition to a dubious aesthetic result after removing the bar (in both cases), lead us to rethink this indication of the Nuss technique. For all these reasons, the surgeon’s experience in the treatment of chest wall deformities and the appropriate indication of the technique are vital to minimise adverse effects and optimise results.19

In our series, in cases corrected by open surgery (Ravitch and variants) we were able to decompress visceral structures and correct the aesthetic defect in part, which was accentuated again when the bar that we placed to stabilise the wall was removed. In second stage surgery, the placement of 3D prostheses can be evaluated if the patient requests it. In no case were there major complications or overcorrection of the defect. In the patients that we had corrected using Nuss or taulinoplasty, when the stabilisation material was removed, the visual wall defect was reproduced between 40 and 90%, making it necessary to reoperate some patients who were not happy with the final result obtained. Consequently, we decided to dispense with these techniques from 2021.

In our series, we fitted a 3D prosthesis in a patient after removing a taulinoplasty screw, as well as in 4 patients who had undergone surgery using the Nuss technique years ago. All of them were already adult patients who were looking to correct the poor aesthetic result. The rest of the cases treated with 3D prostheses were symptom-free patients, whose only indication was to correct a visual defect in the chest wall. Depending on age and psychological involvement, the date of surgery was planned.

In conclusion, we can say that in our opinion, PE surgery should be evaluated as either a structural correction of the wall (open surgery) or an aesthetic one. In the first case, remodelling of the rib cage must be performed, which will require chondrectomies and perhaps partial osteotomies, with the possibility of implanting osteosynthesis material. In the second case, we corrected the defect with a custom-made 3D prosthesis. In view of our results, we propose that the Nuss technique and taulinoplasty should be relegated to a rear position and applied for very specific cases, in the opinion of the surgeon responsible for the indication, as these techniques do not achieve permanent remodelling of the rib cage and are more aggressive than the placement of a 3D prosthesis, with potentially more serious complications.

Conflict of interestNone.