To analyze the results obtained in terms of efficacy and safety during the learning curve of a surgical team in the technique of laparoscopic common bile duct exploration with cholecystectomy (LCBDE+LC) using choledochoscopy for the treatment of patients with cholelithiasis and choledocolithiasis or common bile duct stones (CBDS) (CDL).

MethodsSingle-center prospective analysis of patients treated with LCBDE+LC during the first 4 years of implementation of the technique. A descriptive and comparative analysis was carried out between groups according to the transcystic (TCi) or transcolecocal (TCo) approach, and also evolutionary by periods. The effectiveness of the technique was evaluated using the variable success rate and safety through the analysis of the overall complication rate and the bile leak rate as the most frequent adverse effect.

ResultsA total of 78 patients were analyzed. The most frequent approach was TCo (62%). The overall success rate was 92%. The TCi group had a shorter operating time, a lower overall complications rate and a shorter hospital stay. The TCo approach was related to a higher rate of clinically relevant bile leak (8%). Complex cases increased significantly during the learning curve without effect on the overall results.

ConclusionsLCBDE+LC is an effective and safe technique during the learning curve. Its results are comparable to those published by more experienced groups and do not present significant differences related to the evolution during learning period.

Analizar los resultados obtenidos en términos de eficacia y seguridad durante la curva de aprendizaje (CA) de un equipo quirúrgico en la técnica de exploración laparoscópica de la vía biliar con colecistectomía (ELVB + CL) mediante coledocoscopia para el tratamiento de pacientes con colelitiasis y coledocolitiasis (CDL) concomitantes.

MétodosAnálisis prospectivo unicéntrico de los pacientes intervenidos mediante ELVB + CL durante los 4 primeros años de implementación de la técnica. Se realizó un análisis descriptivo, comparativo entre grupos según abordaje transcístico (TCi) o transcolecocal (TCo) y evolutivo por períodos. Se evaluó la eficacia de la técnica mediante la variable “tasa de éxito” y la seguridad mediante la “tasa de complicaciones globales” y la “tasa de fuga biliar” como efecto adverso más frecuente.

ResultadosSe analizaron un total de 78 pacientes. El abordaje más frecuente fue el TCo (62%). La tasa de éxito global fue del 92%. El grupo TCi presentó menor tiempo operatorio, menor tasa de complicaciones globales y menor estancia hospitalaria media. El abordaje TCo se relacionó con una mayor tasa de fuga biliar clínicamente relevante (8%). Durante la CA se incrementaron significativamente los casos complejos sin efecto sobre los resultados globales.

ConclusionesLa implementación de la ELVB + CL se demuestra eficaz y segura durante la CA. Sus resultados son equiparables a los publicados por grupos de mayor experiencia y no presentan diferencias significativas relacionadas con la evolución durante dicho período.

Laparoscopic exploration of the bile duct with associated cholecystectomy (LCBDE+LC) using choledochoscopy is a validated technique for the single-stage approach in the case of patients with concomitant cholelithiasis and choledocolithiasis (CLD) or common bile duct stones (CBDS) (CDL). The development of high-tech choledochoscopes over the last decade has produced a boom in this technique, and numerous published studies have already demonstrated its positive results, in both clinical and cost-effective terms when compared to the classic two-stage approach using endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and subsequent laparoscopic cholecystectomy (ERCP+LC).1–5 The most current clinical guidelines6 and expert consensus7,8 propose LCBDE+LC as a safe and effective technique for the management of these patients, which avoids short- and long-term complications of ERCP.9,10

Despite this, in our environment there are few centres that advocate LCBDE+LC as the approach of choice, this being the first option in only 11% of the centres that responded to the national survey published by Jorba et al. in 2020.11 The introduction of the technique at a centre involves certain difficulties, such as the need for economic investment, the training of the surgical team, and the justification of associated expenses or morbidities when compared to the more than established ERCP+LC technique. All of this means that the implementation of LCBDE+LC may get off to a difficult start or even be discarded from the outset. There are few published studies that describe the experience during the learning curve (LeC) in this technique and that undertake a critical analysis of the technical aspects to be improved.12

The main objective of this study was to analyse the results obtained in terms of efficacy and safety during the implementation of the LCBDE+LC technique at our centre. The secondary objectives have focussed on assessing the comparative results between the transcystic approach (TCi) and transcholedochal approach (TCo) and evaluating the outcomes during the LeC or learning curve by means of a comparative sub-analysis over different periods.

MethodsA prospective analysis was run on all patients operated on after diagnosis of cholelithiasis and CDL using LCBDE+LC from the start of use of the technique at one same centre (March 2019 to April 2023).

Demographic data, medical history, current illness (obstructive jaundice, cholangitis, cholecystitis or acute pancreatitis) and laboratory tests were collected.

The initial radiological study was run using abdominal ultrasound and/or abdominal CT scan, depending on the case. In view of the intermediate or high suspicion of concomitant CDL, according to the criteria of the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 2019,13 the study with cholangio magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) was completed to confirm CDL and preoperative anatomical study of the bile duct.

LCBDE+LC was indicated in patients with a confirmed radiological diagnosis of cholelithiasis and CDL. The complexity progressively increased with the technical development of the equipment, including cases of interlocking or cobblestone CDLs. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarised in Fig. 1.

The surgery was performed in all cases by two surgeons with no previous experience in LCBDE+LC using choledochoscopy. Prior to the implementation of the technique, they had undergone specific training by attending live courses and surgeries.

The LeC or learning curve was defined as the period from the completion of the first case (March 2019) up to case number 78 (April 2022), considering this value to be necessary to pass the learning stage, as demonstrated in the systematic review by Chan et al.14

Surgical techniqueFor the LCBDE+LC, the French position with 4 trocars was used, adding a fifth accessory portal if necessary. Intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) was performed systematically to confirm the persistence of CDL.

A TCi approach was adopted in cases where it was technically possible to cannulate the cystic duct with the choledochoscope, and its diameter enabled extraction of the CDL. A longitudinal choledochotomy was performed using a cold scalpel in all patients who underwent TCo, adapting the size of the incision to the size of the CDL to be extracted. Lithotripsy was not performed in any case due to lack of availability of the necessary technology, so the decision to approach TCi or TCo was based on anatomical characteristics only.

Flexible 3 mm calibre choledoscopes were used for the TCi approach and 5 mm for the TCo. At the beginning of the LeC or learning curve, inventory-monitorable fibre-choledoscopes were used, progressively incorporating the use of single-use video choledochoscopes from case number 30 in the series.

For the extraction of the CDLs, pressure washing manoeuvres (flushing), single-use expandable baskets and Fogarty® type ball passes were used as needed. The administration of glucagon or buscapine was associated with promoting relaxation of the Oddi sphincter where necessary. In the TCi approach, the "Wiper Blade Maneuver" was performed for examination of the intrahepatic bile duct, depending on technical possibilities.15

In the TCo approach, priority was given to primary closure of the choledochotomy by continuous suture of 4-5/0 polydioxanone monofilament, switching to the use of the 4/0 barbed suture from case number 61 in the series. Kehr tube closure was only performed in cases with suspected choledochal lesion due to diathermy. Metal or Hem-o-lock® clips were applied for the closure of the cystic duct and subhepatic Jackson-Pratt drainage was left in all cases.

TrackingThe efficacy of the technique was measured using the variable "success rate", which was defined as the percentage of patients in whom a complete cleansing of the bile duct was achieved using the LCBDE+LC procedure.

The safety of the technique was measured using the variables "overall postoperative complication rate" and "biliary leak rate". Local and general postoperative complications were collected according to the Clavien–Dindo classification and the Comprehensive Complication Index (CCI ®). Biliary leakage was defined as the outflow of bile collected by the drainage during the immediate postoperative period. The type of biliary leak was defined according to the classification of the International Study Group on Liver Surgery,16 with type A biliary leakage being the type which did not cause changes in clinical management, type B required therapeutic intervention without requiring reoperation, and type C required repeat operation. Type B and C biliary leaks were defined and grouped as "clinically relevant biliary leakage".

Postoperative variables assessed included hospital stay (days), need for reoperation, need for readmission, and related mortality in the 90 days postoperatively.

Follow-up was clinical and analytical in all cases, including imaging with CMRI only when CDL persistence or recurrence was suspected.

The persistence of CDL or Residual CDL in those cases in which complete clearance of the common bile duct could not be performed in surgery or in the case of diagnosis of CDL (by imaging test or ERCP) during the first 6 months postoperatively.

Recurrence was defined as the diagnosis of CDL by imaging test or ERCP 6 months after initial surgery.

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis was run for the main objective. Continuous variables were expressed by calculating measures of central tendency (mean or median), dispersal (standard deviation and range), and qualitative variables according to frequency and percentage.

Subsequently, a bivariate comparative analysis was run between TCi and TCo groups using the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and the Student's T or U-Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables according to their normal distribution. For the evolutionary analysis of LeC or learning curve, patients were divided into 4 groups by periods: GROUP1 (patient 1–20), GROUP2 (21–40), GROUP3 (41–60) and GROUP4 (61–78). A comparative analysis was run using Fisher's Chi-square or exact test for categorical variables and one-way analysis of variance for the comparison of means in continuous variables. All statistical tests were performed bilaterally and a value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

To run the statistical analysis, the Jamovi programme version 2.2.3 (Jamovi Project, 2018, https://www.jamovi.org/) was used.

ResultsOverall resultsA total of 86 patients underwent surgery over the period described, with clinical and radiological diagnosis of cholelithiasis and CDL. In 8 cases (9%) the IOC was negative for CDL without the need to continue with the LCBDE+LC. We present the results of the 78 patients on whom we performed LCBDE+LC by choledochoscopy.

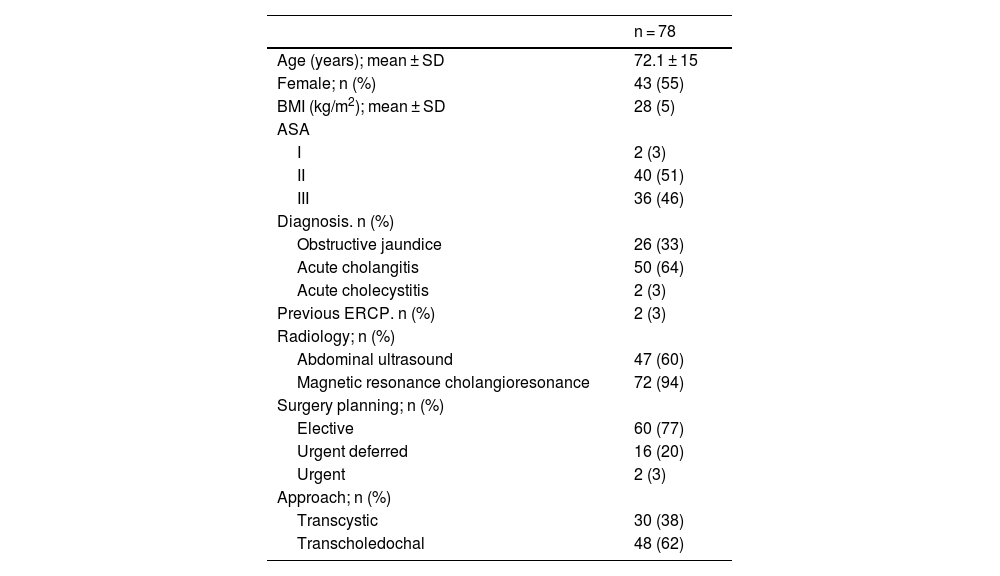

The baseline characteristics of these patients are summarised in Table 1. The TCi approach was achieved in 30 patients (38%).

Global baseline characteristics.

| n = 78 | |

|---|---|

| Age (years); mean ± SD | 72.1 ± 15 |

| Female; n (%) | 43 (55) |

| BMI (kg/m2); mean ± SD | 28 (5) |

| ASA | |

| I | 2 (3) |

| II | 40 (51) |

| III | 36 (46) |

| Diagnosis. n (%) | |

| Obstructive jaundice | 26 (33) |

| Acute cholangitis | 50 (64) |

| Acute cholecystitis | 2 (3) |

| Previous ERCP. n (%) | 2 (3) |

| Radiology; n (%) | |

| Abdominal ultrasound | 47 (60) |

| Magnetic resonance cholangioresonance | 72 (94) |

| Surgery planning; n (%) | |

| Elective | 60 (77) |

| Urgent deferred | 16 (20) |

| Urgent | 2 (3) |

| Approach; n (%) | |

| Transcystic | 30 (38) |

| Transcholedochal | 48 (62) |

SD: Standard Deviation; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde Cholangiopancreatography.

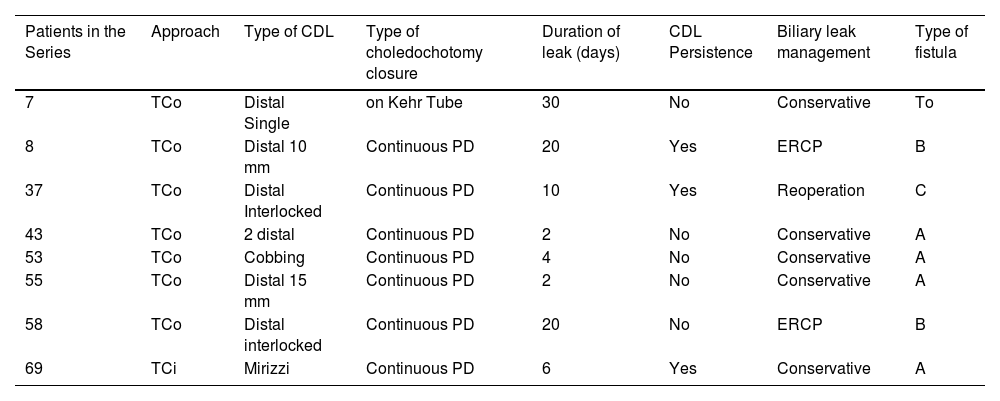

Overall postoperative outcomes are described in Table 2. The overall success rate was 92%. Of the 6 cases with residual CDL (8%), ERCP was performed on 5 patients in the immediate postoperative period and one required reoperation due to secondary biliary leakage and choleperitoneum. The most common postoperative complication was biliary leakage in 8 cases (10%), and biliary leakage was clinically relevant in 3 patients (4%). Table 3 summarises the characteristics of patients with postoperative biliary leakage.

Overall postoperative results.

| n = 78 | |

|---|---|

| Surgery Time (min); Median (Range) | 180 (75−420) |

| Success rate. n (%) | 72 (92) |

| Residual CDL. n (%) | 6 (8) |

| Conversion to open surgery, n (%) | 5 (6) |

| Conversion to a different technique, n (%) | 6 (8) |

| Overall complications. n (%) | 17 (22) |

| Total biliary leakage | 8 (10) |

| Type A | 5 (6) |

| Type B | 2 (3) |

| Type C | 1 (1) |

| Clinically relevant biliary leakage | 3 (4) |

| Paralytic ileus | 2 (3) |

| Superficial wound infection | 2 (3) |

| Pancreatitis | 1 (1) |

| Cholangitis | 1 (1) |

| Intraabdominal haematoma | 1 (1) |

| Acute urinary retention | 1 (1) |

| Diarrhoea | 1 (1) |

| Complications Clavien Dindo ≥ III., n (%) | 5 (6) |

| CCI ®; mean ± SD | 3.7 ± 8 |

| Reoperation. n (%) | 1 (1) |

| Hospital stay (days); Median (range) | 4 (0−29) |

| Mortality, n (%) | 0 |

| Readmissions, n (%) | 8 (10) |

| Follow-up (days); mean ± SD | 270 (182−1021) |

| CDL recurrence, n (%) | 3 (4) |

SD: Standard Deviation; CDL: Choledocholithiasis; CCI: Comprehensive Complication Index.

Details of patients with postoperative biliary leakage.

| Patients in the Series | Approach | Type of CDL | Type of choledochotomy closure | Duration of leak (days) | CDL Persistence | Biliary leak management | Type of fistula |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | TCo | Distal Single | on Kehr Tube | 30 | No | Conservative | To |

| 8 | TCo | Distal 10 mm | Continuous PD | 20 | Yes | ERCP | B |

| 37 | TCo | Distal Interlocked | Continuous PD | 10 | Yes | Reoperation | C |

| 43 | TCo | 2 distal | Continuous PD | 2 | No | Conservative | A |

| 53 | TCo | Cobbing | Continuous PD | 4 | No | Conservative | A |

| 55 | TCo | Distal 15 mm | Continuous PD | 2 | No | Conservative | A |

| 58 | TCo | Distal interlocked | Continuous PD | 20 | No | ERCP | B |

| 69 | TCi | Mirizzi | Continuous PD | 6 | Yes | Conservative | A |

TCo: Ttranscholedochal; TCi: Transcystic; CDL: Choledocholithiasis; Pd: Polydioxanone; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

The mean overall follow-up was 9 months, with 3 patients (4%) being diagnosed with recurrence at 10, 19 and 26 months after surgery, respectively.

Comparative results between TCi vs. TCo groupThese are summarised in Tables 4 and 5. The two groups were homogeneous in terms of demographic and clinical characteristics. The diameter of the CBD pathway and the diameter of the larger CDL were significantly higher in the TCo group, since the approach was selected according to anatomical characteristics.

Comparative baseline characteristics between approaches.

| Transcystic | Transchole- dochal | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 30 (38) | 48 (62) | |

| Age (years); mean ± SD | 69.2 (18) | 74 (13) | 0.456 |

| Female; n (%) | 19 (63) | 24 (50) | 0.249 |

| BMI (kg/m2); mean ± SD | 27.9 (6) | 28 (4) | 0.931 |

| ASA I | 2 (7) | 0 | 0.192 |

| II | 15 (50) | 25 (52) | |

| III | 13 (43) | 23 (48) | |

| Diagnosis. n (%) | |||

| Obstructive jaundice | 11 (37) | 15 (31) | 0.818 |

| Acute cholangitis | 18 (60) | 32 (67) | |

| Acute cholecystitis | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | |

| Previous ERCP, n (%) | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | 0.734 |

| Preoperative analytical values; mean ± SD | |||

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 2.35 (3.5) | 2.56 (3.2) | 0.309 |

| AST (UI/I 37C) | 91.41 (11.7) | 93.62 (141.3) | 0.966 |

| ALT (IU/S 37C) | 145.79 (174.8) | 149.9 (297.5) | 0.685 |

| GGT (U/L) | 435.37 (307.2) | 697.7(529) | 0.05 |

| ALP(U/L) | 214.7 (202) | 397 (376) | 0.008 |

| Maximum diameter CBD (mm); mean ± SD | 8.64 (2.6) | 13.13 (3.8) | <0.001 |

| Maximum diameter CDL greater (mm); mean ± SD | 6.62 (4.8) | 10.62 (5.1) | <0.001 |

SD: Standard Deviation; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; GGT: Gamma-glutamyl transferase; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; CBD: Common bile duct; CDL: Choledocholithiasis.

Bold values were only to remark the significant results.

Comparative postoperative results between approaches.

| Transcystic | Transchole-dochal | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 30 (38) | 48 (62) | |

| Surgery Time (min); Median (Range) | 157.5 (75−420) | 180 (90−350) | 0.046 |

| Success rate, n (%) | 26 (87) | 46 (96) | 0.139 |

| Residual lithiasis, n (%) | 4 (13) | 2 (4) | 0.139 |

| Conversion to open surgery. n (%) | 0 (0) | 5 (10) | 0.068 |

| Conversion to a different technique. n (%) | 4 (13) | 2 (4) | 0.139 |

| Overall complications, n (%) | 2 (7) | 15 (31) | 0.011 |

| Total biliary leakage | 1 (3) | 7 (15) | 0.111 |

| Type A | 1 (3) | 4 (8) | |

| Type B | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | |

| Type C | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | |

| Clinically relevant biliary leakage | 0 | 4 (8) | 0.105 |

| Complications Clavien Dindo ≥ III. n (%) | 1 (3) | 4 (8) | 0.410 |

| CCI ®; mean ± SD | 1.1 ± 5 | 5.3 ± 9 | 0.012 |

| Reoperation, n (%) | 0 | 1 (2.1) | 0.426 |

| Hospital stay (days); Median (range) | 2 (0−14) | 4 (2−29) | <0.001 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Readmissions, n (%) | 3 (10) | 5 (10) | 0.953 |

| Follow-up (days); median (range) | 370 (182−1002) | 392 (730−1021) | 0.381 |

| CDL recurrence, n (%) | 1 (3) | 2 (4) | 0.853 |

CDL: Choledocholelithiasis; CCI: Comprehensive Complication Index.

Bold values were only to remark the significant results.

The success rate was 87% in the TCi group and 96% in the TCo approach. The TCi group had significantly shorter surgery time, a lower overall complication rate, a lower mean CCI ® and a shorter hospital stay. Although not statistically significant, the TCo group had a higher rate of overall biliary leakage (15% vs. 3, p = 0.111) and clinically relevant biliary leakage (8% vs. 0, p = 0.105). Of the patients treated with the TCi approach, none had clinically relevant biliary leakage.

There was no difference in the number of reoperation, readmissions or recurrences between groups.

Comparative results between periodsThese are summarised in Table 6. The percentage of patients treated with 4 or more CDL increased significantly during the LeC or learning curve with no significant impact on success rate, number or degree of complications, hospital stay, reoperations, readmissions or recurrence between the periods.

Comparative results between periods.

| GROUP1 | GROUP2 | GROUP3 | GROUP4 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 20 | 20 | 20 | 18 | |

| TCi approach. n (%) | 7 (23) | 8 (27) | 7 (23) | 8 (27) | 0.920 |

| 4 or more CDL, n (%) | 3 (15) | 7 (35) | 10 (50) | 10 (56) | 0.040 |

| Surgery time (min); mean ± SD | 211 ± 62 | 163 ± 52 | 178 ± 65 | 179 ± 77 | 0.085 |

| Success rate, n (%) | 18 (90) | 18 (90) | 20 (100) | 16 (90) | 0.520 |

| Conversion to open surgery, n (%) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 3 (15) | 0 | 0.281 |

| Overall complications. n (%) | 3 (18) | 3 (18) | 7 (41) | 4 (23) | 0.424 |

| Total biliary leakage | 2 (10) | 1 (5) | 4 (20) | 1 (6) | 0.508 |

| Clinically relevant biliary leakage | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 0 | 0.817 |

| Complications C–D ≥ III, n (%) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 2 (10) | 1 (5) | 0.067 |

| CCI ®; mean ± SD | 3.4 ± 8 | 2.5 ± 8 | 4.8 ± 8 | 4.2 ± 9 | 0.836 |

| Reoperation. n (%) | 0 | 1 (5) | 0 | 0 | 0.401 |

| Hospital stay (days); mean ± SD | 5.6 ± 7 | 3.5 ± 2 | 5.2 ± 6 | 4 ± 5 | 0.404 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Readmissions, n (%) | 3 (15) | 3 (15) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 0.570 |

| CDL recurrence, n (%) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 0 | 0.583 |

TCi: Transcystic; SD: standard deviation. C-D: Clavien–Dindo; CCI: Comprehensive Complication Index; CDL: choledocholithiasis.

Bold value were only to remark the significant results.

Our series reflects the results obtained during the LeC or learning curve of the LCBDE+LC technique using choledochoscopy in our group. Since this is a constantly evolving technique, regular analysis of the results is of vital importance to evaluate efficacy and safety during its implementation.17

In terms of efficacy, our series has achieved an overall success rate of more than 90%, which is comparable to what has been published in the most recent literature, which is 75–97.6%.1,7,18,19 It should be noted that our cohort considers a failure rate of 13% for the TCi approach compared to 4% for the TCo approach. Such failure has already been shown to be related to different risk factors,18,20,21 such as failed preoperative ERCP, the presence of pediculitis in the CBD, the presence of impacted CDL, diameter of the CBD <4 mm, longer operating time, or years of experience of the surgeon. Our series does not show a significant relationship between this failure and the evolutionary analysis of the LeC or learning curve. Lithotripsy has shown an increase in the success rate of the TCi approach in some series,20,22 which may be a limiting factor in our study. The systematisation of the surgical technique and the availability of specific tools22 are essential to achieve a TCi approach, especially in patients with risk factors for failure.

Our series suggests an overall surgery time of 180 min (75−420) and a significant reduction in the TCi approach. The literature summarising the results during the LeC or learning curve only is very scarce, and the overall surgery times in groups with more experience are shorter (53−170 min). Although our series does not show statistically significant differences between the different duration of the LeC or learning curve, it is reasonable to think that this surgery time can be reduced with the technical development of the surgical team. Many current publications are describing manoeuvres and technical details that can improve operating time.15,23–26

In relation to the safety of the technique, our series describes a relevant complication rate of 6%, which is in the range published by the groups with the most experience (2.5–9%).7,18,19 The evolution over the course of the LeC or learning curve has shown a significant increase in the complexity of cases (patients with 4 or more CDL) without significantly affecting postoperative outcomes. The TCi approach shows a significantly lower mean CCI ® than the TCo, with biliary leakage being the main specific complication in the latter category.7,18,19

Without detailing its clinical significance, the literature describes an incidence of postoperative biliary leakage of around 3.5–8.4%. The clinically relevant percentage of biliary leakage in our series is in line with what has been described, with an overall value of 4%. Different studies demonstrate the benefits of primary choledochal suture compared to Kehr tube closure in the TCo approach.21,26 Even so, primary choledocorrhaphy generally increases the risk of postoperative biliary leakage compared to the usual single closure using cystic duct clips in the TCi pathway. The failing of this suture may be increased in different situations: a technical error, residual CDL or postoperative odditis. In view of these factors, the use of a transcystic drain to protect the suture may be helpful in reducing the risk of biliary leakage. In our series, we did not observe any TCo biliary leakage after the introduction of the barbed suture (GROUP4). Further studies would be needed to determine whether such this suture may become a protective factor against biliary leakage.

The evolutionary analysis by periods in our series has not shown significant differences in hospital stay or readmissions, and the results in these terms are also comparable to the published literature.

Despite being a single-centre series with a limited number of patients, being not possible to rule out a selection bias as these were patients adapted to the technical skills of the team in training, our analysis summarises the real LeC or learning curve of a group and shows that its results are comparable to those published by the groups with more experience, without being affected by the period of skill development. This reinforces the fact that the LeC or learning curve in the LCBDE+LC can be effective and safe throughout its development and supports its implementation. The sub-analysis between approaches reveals results consistent with the literature in demonstrating that the TCi approach is related to a lower overall postoperative morbidity rate, lower incidence of clinically relevant biliary leakage and shorter hospital stay,4,7,12,18,19 resulting in the approach to be prioritised. The appropriate selection of patients, the systematisation of the technique and the availability of appropriate tools, such as lithotripsy, could help to achieve a higher percentage of success in the TCi approach and reduce the morbidity associated with the TCo approach.

The authors would like to express their sincere thanks to P. Ubieto, G. Llanos, M.de la Iglesia, A. Martín, and all the rest of the surgical nursing team for their dedication to this project, and to Dr. X. Suñol for making the beginnings possible.