Review articles are characterised by the synthesis of scientific knowledge. Traditionally, synthesis articles differentiated between a narrative review, the essential characteristic of which is the absence of a clear methodology, and a systematic review (SR) where an explicit and reproducible methodology is salient. SRs are secondary studies aimed at responding to a research question, for which they carry out exhaustive searches of the evidence and summarise the results found in the said investigations.1 The SR is often accompanied by a meta-analysis (MA), a statistical analysis of the combination of the results of the evaluated documents. The SR/MA is considered the study with the greatest scientific evidence for medical decision making.2 In recent years, other synthesis documents have been developed, the most prominent of which are the exploratory review, the network meta-analysis and the umbrella review meta-analysis.1

The critical appraisal of a scientific article is defined as the rigorous and critical analysis of the article validity, the interpretation of results, and their possible relevance.3 The critical reading of an SR/MA involves the analysis and verification of the main points of its redaction4,5:

- 1

Formulation of a well-defined clinical question. This is equivalent to the research hypothesis that gave rise to the article. The research question is usually structured, using the acronym PICO, defining the population analysed (P), the intervention or exposure factor to be evaluated (I), the comparative (C) and the analysed outcome (O).

- 2

Selection of articles. The inclusion and exclusion criteria of the articles to be assessed will be determined by the researchers and will be in keeping with the research question. Criteria are multiple but the most salient is the original study design - for example, the evaluation of a treatment is made through analysis of controlled and randomised trials.

- 3

Systematic search of the relevant documents. This is the key point of an SR/MA, which is undertaken by exploring electronic databases. It must be carried out by at least two people independently, and it is recommended that information documentalists be included. The main components of an appropriate search are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.Components of an exhaustive search of the literature.

1. Search for published and non-published articles - •

Databases and search platforms

- o

Randomised clinical trials: Medline, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials.

- o

Databases of specific geographic areas if the topic of interest is located in these areas.

- o

Specific databases for certain areas of health, nursing, psychology, etc.

- •

Clinical trial records

- •

Monitoring of bibliographic references in selected articles and previous reviews.

- •

Contact with experts and research promoters on the topic analysed.

- •

Medical congress repertoires.

- •

Doctoral theses.

2. Search terms - •

Key words which address components of the clinical question.

- •

Boolean operators.

- •

Free text with the use of synonyms recommended.

3. Time period - •

Not excessive (6–12 months) between termination of the search and publication of the study.

4. Graphical representation of the literature search process - •

Flow diagram.

- •

- 4

Assessment of the articles and data extraction. It is also recommended that the selection, article assessment, and relevant data extraction be carried out by at least two researchers independently. The main characteristics of the included studies should be shown in a table.

- 5

Analysis of the quality of the original articles. Assessing the risk of bias in the original articles is another essential point. Again, it requires at least two independent evaluators and is usually carried out using a bias evaluation scale. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias is the most used here, with risk of bias grading. The presence of a greater number of biases conditions the degree of recommendation and applicability of the intervention.6

- 6

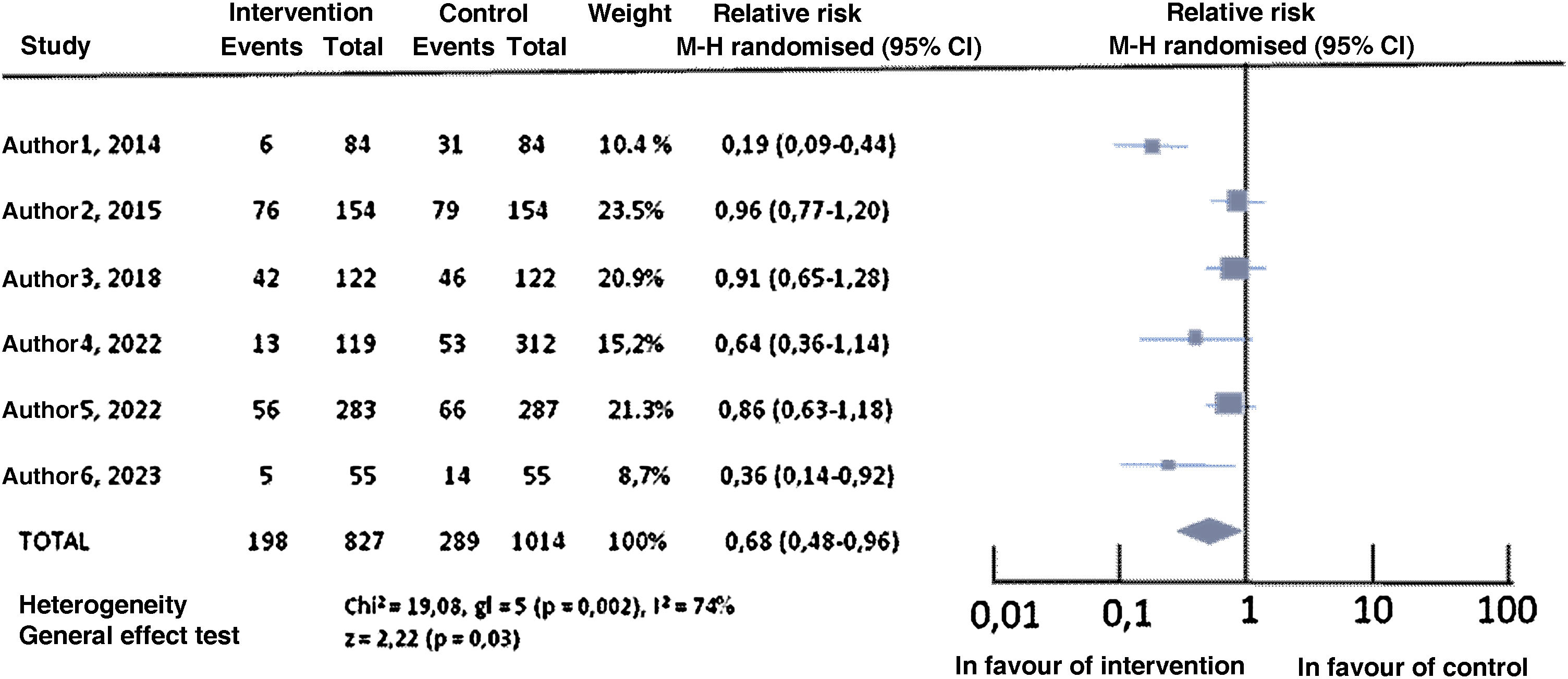

Analysis of heterogeneity. The selected articles show differences related to the study design. As a result, heterogeneity must be evaluated and analysed since it indicates whether the results of the original studies can be combined and offer a global estimation of the results. Heterogeneity analysis begins by visually inspecting the MA graph. Major differences in point estimates or non-overlapping confidence intervals suggest heterogeneity. Statistical tools also exist. The most used are Cochrane’s Q test and the I2 test. The latter offers a quantitative result of the heterogeneity and must be shown in the graphical representation of the MA.

- 7

Review results. In SRs the synthesis of analysed studies is performed through text or table. However, the statistical analysis of the combination of results from the original studies is shown in the MA forest plot (Fig. 1). The results shown may be binary, and the most frequently represented measures of effect are relative risk, odds ratio, or risk difference. For quantitative data, mean differences are usually shown. They must be accompanied by 95% confidence intervals, that state the precision of the results. Combining the results can be done in two ways, using the random effects model or the fixed effects model. The choice of model is usually determined by the presence of heterogeneity. If this occurs, the random effects model is used with more conservative results. Subgroup analysis is common, but must be previously defined in the study protocol.

Fig. 1.Forest plot (own production). Forest plot components: 1st column: author/year and total; 2nd column: intervention group results; 3rd column: control group results; 4th column: study weight (contribution of the study to the total MA); 5th column: estimator of effect and 95% confidence interval, with the statistical calculation method; 6th column: graphic representation of the effect estimator (size dependent on the weight of the study) with its confidence intervals (M-H: Mantel-Haenszel test).

- 8

Sensitivity analysis. This is an important complement in an MA. The sensitivity analysis will exclude studies with more extreme results or those with variables that cause heterogeneity, in order to obtain a more homogeneous summary. This analysis is important since, if the results of the different resulting MAs are similar in magnitude, direction and effect, the results are reliable.

- 9

Publication bias. This is characteristic of SR/MAs. This bias occurs when what is published does not represent the total amount of research on a topic.7 The non-inclusion of unpublished studies reduces confidence in the final result. It is therefore necessary to determine this bias, using several tools, such as the funnel plot graph.

- 10

Beneficial/harmful effects and cost of the intervention. It is important for an SR/MA to present the harmful events and even the cost-benefit of the intervention implementation in the event that it has shown a benefit in the evaluated clinical outcome.

- 11

Applicability of the results. The ultimate goal of critical reading is to determine the applicability of the results to a specific patient. To do this, the surgeon must reflect on the differences between the characteristics of their patients and those included in the review. In addition, they must assess other factors, including those related to the doctors at whom the SR/MA is directed. This last point is especially relevant in studies on surgical patients. External validity is more compromised in studies on surgical interventions, where skills can differ greatly between different professionals, and where the learning curve is a determining factor in the success or failure of a new technique.8

The teaching of critical reading of scientific articles is one of the essential contributions of evidence-based medicine. This continues to be a priority in all areas of medicine. Neither the publication in a high-impact journal, nor the presence of peer review, nor following the PRISMA guidelines when carrying out an SR/MA, nor even the completion of work by a highly prestigious organization such as the Cochrane Collaboration ensures the absence of errors in the undertaking of scientific studies.9,10 It therefore remains the surgeon's obligation to determine, through an easy, standardised process, whether or not the results derived from the research should be transferred to the patients they care for.

FundingThe authors have not received any funding for the preparation of this manuscript.