Cholecysto-cutaneous fistulas are a rare surgical entity.1,2 They are associated with complications of cholecystitis, empyema, gallbladder carcinoma with local extension, or after surgery. We present the case of a cholecysto-cutaneous fistula as a form of presentation of gallbladder adenocarcinoma.

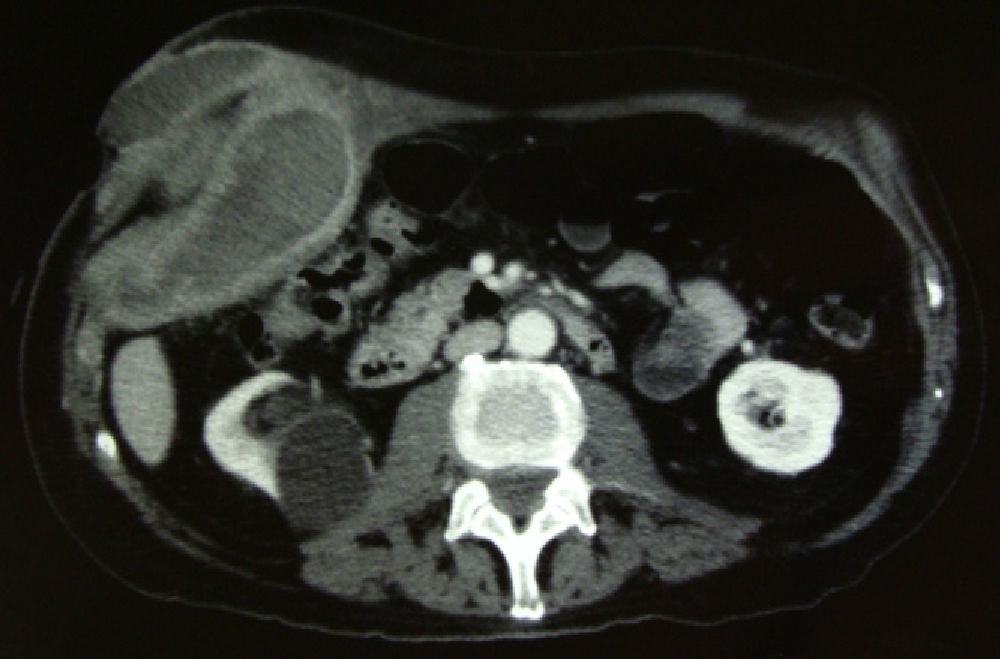

The patient was an 83-year-old male with no prior history except for a previous episode of acute cholecystitis 2 years earlier, which had been treated conservatively with antibiotics and fluid therapy at another hospital. He came to the Emergency Department of our hospital complaining of abdominal pain in the right upper quadrant associated with the oozing of hematic-purulent content through an orifice in the abdominal wall located in the right hypochondrium. Abdominal examination revealed a mass in this region. The patient presented important anemia in the blood work-up (Hb 6g/dl), although he was hemodynamically stable. Abdominal CT demonstrated a collection measuring 98mm×78mm×90mm that was located predominantly in the extraperitoneal region, with hematic content in its interior, extending from the gallbladder bed to the subcutaneous tissue that fistulized through the skin (Figs. 1 and 2). A right subcostal laparotomy was performed; a large hematoma situated in the gallbladder bed was evacuated, the gallbladder and the fistulous tract from the gallbladder fundus to the abdominal wall were removed. The cutaneous fistula orifice was excised with the associated cholecystectomy. The pathology study reported moderately differentiated papillary adenocarcinoma, with infiltration of the cystic duct and abdominal wall (T3N0M0). The patient was discharged after an uneventful postoperative recovery.

Neoplasms of the bile duct are uncommon and are associated with a poor prognosis. Gallbladder carcinoma (GBC) represents 3% of malignant tumors and is fifth in the order of frequency within the group of gastrointestinal malignant neoplasms. The annual incidence of GBC ranges between 2 and 13/100 000 inhabitants. The most common age of presentation is between 65 and 75. In 95% of cases, the most frequent histologic type is adenocarcinoma, and there seems to be a clear association with cholelithiasis, porcelain gallbladder, repeated gallbladder infections, bile duct anomalies and benign gallbladder tumors, among others. Gallstones are the main associated factor; some studies have found that the risk for developing GBC in patients with gallstones is 1%–3%.3,4 As for the pathogenesis of this entity, chronic inflammation due to several stimuli has been implicated, and it is thought that the adenoma–carcinoma sequence is present in many cases of GBC.5

Early-stage GBC presents with non-specific symptoms that are similar to cholelithiasis, while in advanced cancer more significant symptoms can appear, such as weight loss, jaundice, anorexia, ascites and palpable mass in the right hypochondrium, associated with a poorer prognosis and tumor irresectability. Because of this presentation, less than 50% of GBC cases are diagnosed preoperatively; many are incidental findings after cholecystectomies due to cholecystitis or biliary colic.3,5 In these cases and depending on the pTNM, re-laparotomy is often necessary for radical cholecystectomy (resection of segments ivb and v as well as hilar lymphadenectomy).4

The mortality of this disease is related to the degree of locoregional tumor dissemination. Most GBC cases are diagnosed in late stages, with a 5-year survival rate of only 5%.3,6,7 Currently, some groups have reported 5-year survival rates between 61%–80% and 30%–45% in stages T2 and T3, respectively, after extensive radical cholecystectomy, suggesting that adequate surgical management with R0 resections can improve the results in patients with GBC.4

In this patient in particular, a second procedure for radical surgery was ruled out given the patient's age, general state and advanced disease.

Despite not being a common form of presentation, isolated cases have been described of spontaneous cholecysto-cutaneous fistula due to gallbladder carcinoma. Spontaneous cholecysto-cutaneous fistula is a rare surgical entity that was first described by Thilesus in 1670. It is becoming a less and less common disease due to the early diagnosis and surgical management of biliary lithiasis, and 226 cases have been published to date.1,2 This disease presents fundamentally as a complication of a lithiasic inflammatory process, and corresponds with the spontaneous evolution of untreated gallbladder empyema, although there have been cases described of fistulas secondary to acalculous cholecystitis or gallbladder carcinoma.2 The gallbladder perforation generally occurs in the fundus and, once this happens, the gallbladder is able to freely drain into the abdominal cavity or adhere to neighboring structures, causing internal fistulas or, less frequently, toward the abdominal wall as external fistulas. The presentation of the fistula may be evident by observing the discharge of bile or calculi to the abdominal wall. In more difficult situations, there may be drainage of pus, leading one to consider pathologies such as infected epidermal cyst, tuberculoma, pyogenic granuloma, metastatic carcinoma or chronic costal osteomyelitis within the differential diagnosis.1,5,8

Please cite this article as: Ugalde Serrano P, Solar García L, Miyar de León A, González-Pinto Arrillaga I, González González J. Fístula colecistocutánea como forma de presentación del adenocarcinoma de vesícula biliar. Cir Esp. 2013;91:396–397.