Controversy exists in the literature as to the best technique for pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD), whether pyloric preservation (PP-CPD) or Whipple's technique (with antrectomy [W-CPD]), the former being associated with a higher frequency of delayed gastric emptying (DGE).

MethodsRetrospective and comparative study between PP-CPD technique (n = 124 patients) and W-CPD technique (n = 126 patients), in patients who were operated for tumors of the pancreatic head and periampullary region between the period 2012 and 2023.

ResultsSurgical time was longer, although not significant, with the W-CPD technique. Pancreatic and peripancreatic tumor invasion (p = 0.031) and number of lymph nodes resected (p < 0.0001) reached statistical significance in W-CPD, although there was no significant difference between the groups in terms of lymph node tumor invasion.

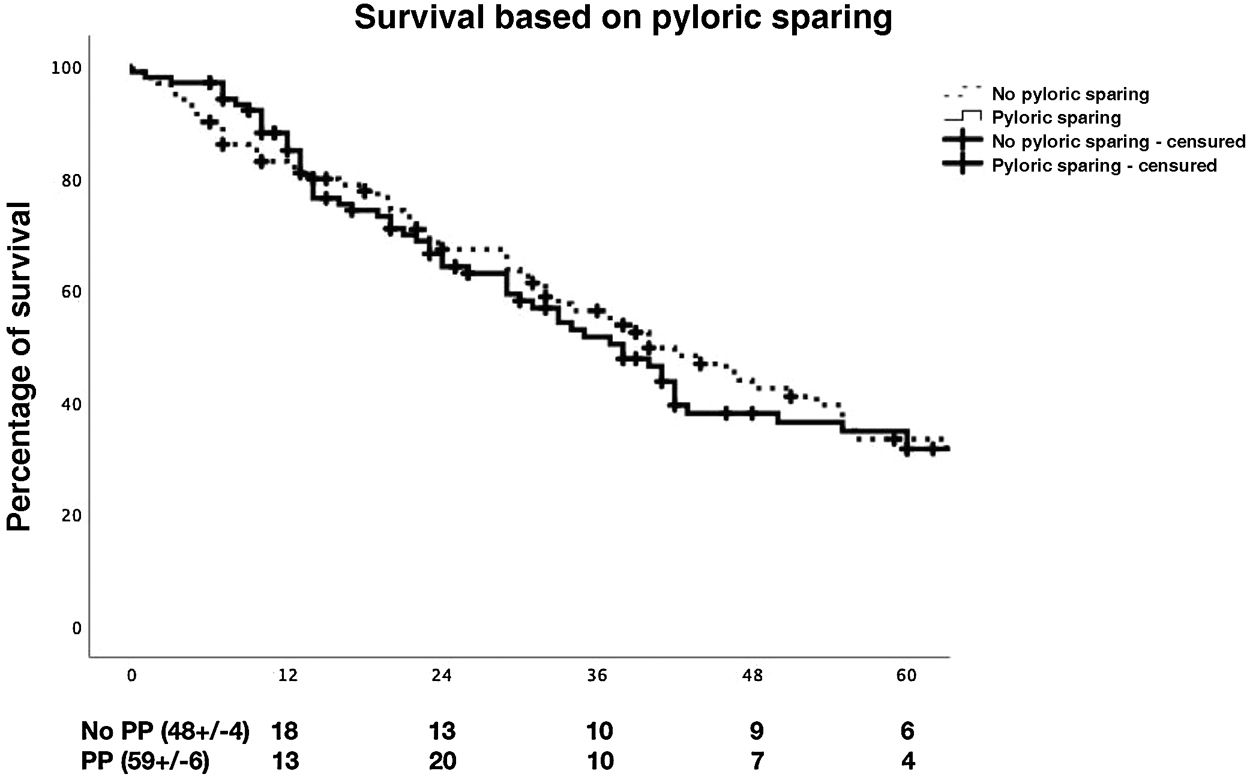

Regarding postoperative morbimortality (medical complications, postoperative pancreatic fistula [POPF], hemorrhage, RVG, re-interventions, in-hospital mortality, Clavien–Dindo complications), ICU and hospital stay, no statistically significant differences were observed between the groups. During follow-up, no significant differences were observed between the groups for morbidity and mortality at 90 days and survival at 1, 3 and 5 years. Binary logistic regression analysis for DGE showed that binary relevant POPF grade B/C was a significant risk factor for DGE.

ConclusionsPostoperative morbidity and mortality and long-term survival were not significantly different with PP-CPD and W-CPD, but POPF grade B/C was a risk factor for DGE grade C.

Existe controversia en la literatura en cuanto a cuál es la mejor técnica de duodenopancreatectomía cefálica (DPC), si la de la preservación pilórica (DPC-PP) o la de Whipple (con antrectomía [DPC-W]), asociándose la primera a una mayor frecuencia del retraso en el vaciamiento gástrico (RVG).

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo y comparativo entre la técnica DPC-PP (n = 124 pacientes) y la DPC-W (n = 126), utilizadas en pacientes operados, entre y 2012–2023, por tumores de cabeza de páncreas y periampulares.

ResultadosEl tiempo de cirugía fue mayor, aunque no significativo, con la técnica de DPC-W. La invasión tumoral pancreática y peripancreática (p = 0,031) y el número de ganglios resecados (p < 0,0001) alcanzaron significación estadística en DPC-W, aunque no hubo diferencias significativas entre los grupos en cuanto a la invasión tumoral ganglionar.

Con respecto a la morbimortalidad posoperatoria (complicaciones médicas, fístula pancreática [FPPO], hemorragia, RVG, reintervenciones, mortalidad intrahospitalaria, complicaciones según Clavien–Dindo), estancia en UCI y hospitalaria, no se observaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre los grupos. Durante el seguimiento tampoco se observaron diferencias significativas entre los grupos con relación a la morbilidad y mortalidad a 90 días y supervivencia a 1, 3 y 5 años. En el análisis de regresión logística binaria para el RVG se observó que la FPPO relevante binaria B/C fue un factor de riesgo del desarrollo del RVG.

ConclusionesLa morbimortalidad posoperatoria y supervivencia a largo plazo no fueron significativamente diferentes con la DPC-PP y DPC-W, pero la FPPO binaria B/C fue un factor de riesgo de RVG grado C.

Cephalic duodenopancreatectomy (CPD) is the standard treatment for benign and malignant tumours of the pancreatic head and periampullary region.1 Whipple's CPD (W-CPD) consists of a en bloc resection of the pancreatic head, duodenum, gallbladder, distal bile duct, antrectomy and lymphadenectomy of adjacent lymph nodes with gastrointestinal reconstruction,2 while in the case of the pyloric preservation technique the only difference from the previous one is that the antrum, pylorus and 2−3 cm of the proximal duodenum (PP-CDP) are preserved. This modification was devised in 1944 by Watson3 and reintroduced in 1978 by Traverso and Longmire.4

The use of one or other technique has generated controversy in the literature as to which is the one that is associated with better results. Thus, several studies have observed similar results with PP-CPD and W-CPD with respect to surgical time, blood loss and intraoperative transfusion,5–9 postoperative morbidity and mortality, overall survival,5,10–12 nutritional status and quality of life,8 although in a recent study PP-CPD was a risk factor for long-term complications (biliary stenosis, cholangitis or pancreatitis).12 On the other hand, several studies have shown that surgery time, intraoperative blood loss, and the need for transfusion were significantly shorter in patients with PP-CPD.10,11,13

Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) is a frequent post-CPD complication associated with prolonged hospital stay, with discordant incidence in the different comparative studies on W-CPD and PP-CPD, with a significantly higher incidence of DGE reported in the case of PP-CPD,10,14–17 while other authors show similar incidences of DGE with both techniques.5,6,8,18–20 Thus, the current results of the different published studies are very heterogeneous and do not provide conclusive evidence of the superiority of one of the two techniques.

The aim of this study was to compare the results obtained with the use of the aforementioned techniques in patients with tumours of the pancreatic head and periampullary region.

MethodsFrom January 2012 to February 2023, a total of 567 patients were diagnosed at our centre with tumours of the pancreatic head or periampullary region, among whom surgery was initially contraindicated in 263 patients due to advanced tumour disease or associated severe comorbidity, while surgery was indicated in the remaining 303. However, among this group of patients, CPD could be performed in only 250. This sample of patients was divided into 2 groups: (1) PP-CPD (n = 124; 49.6%); and (2) W-CPD (n = 126; 50.4%) (Fig. 1). Pyloric preservation or pyloric resection (antrectomy) was performed depending on the location of the tumour and the preferences of the surgeons.

The present study is a retrospective comparative cohort study. A comparison was made between the groups analysing the preoperative and perioperative variables, 90-day morbidity and mortality, survival at 1, 3, and 5 years, and a multivariate analysis of possible risk factors for DGE.

The follow-up on patients in this series was a minimum of 6 months, with the study closing at the end of August 2023, with no evidence of the loss of any of the patients in the groups for the final review. The informed consent was signed by all patients before surgery. The study was carried out in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and subsequent amendments and was approved by the Research Institute but it has not been evaluated by the Ethics Committee as it is a retrospective on

Preoperative biliary drainage and surgical techniquePreoperative biliary drainage was placed when total bilirubin was over 15 mg/dL. PP-CPD was performed when the tumour was distal to the duodenum and it was possible to maintain 2−3 cm of duodenum proximal to the pylorus, with tumour-free margins. The W-CPD was performed when the tumour was close to the first duodenal portion and consisted of a distal gastrectomy (20–30% of the stomach) without vagotomy. In the presence of partial invasion of the portal vein or superior mesenteric vein, the segment of the affected venous wall was resected with subsequent suture or end-to-end anastomosis. End-to-side pancreatic-jejunal reconstruction (biplane, duct-mucosa) and bilio-jejunal reconstruction followed the previously published technique.21 Whether or not to use a pancreatic-jejunal anastomotic tutor was based on the surgeon's experience and preference, as well as the presence of risk factors (Wirsung diameter <3 mm and soft consistency of the pancreas). Duodenum-jejunostomy, in the case of PP-CPD, or gastro-jejunostomy, in the case of W-CPD, were performed in antecolic position, 55−60 cm from the hepatic-jejunal, in end-to-side (biplane and continuous suture). Depending on the preferences of the surgeons, in certain cases an end-to-side gastro-jejunostomy and an end-to-side jejunostomy were performed at the foot of the loop (Roux en Y) to prevent reflux of pancreatic-jejunal secretion into the stomach. The borders analysed by pathological anatomy were the posterior margin of the pancreatic head and SMA, axis of the portal vein and SMV, and the border of the pancreatic section. R1 resection was considered when tumour cellularity was present within 1 mm of the resection margin.

Perioperative careA nasogastric tube (NGT) was placed in all patients. Antibiotic prophylaxis with 2 g of i.v. cefazolin and parenteral nutrition were administered until oral tolerance was initiated. In the absence of complications (fistula, haemorrhage, infection) and with amylase levels due to the drainage <400 IU, the NGT was removed by the 3rd-4th day and the abdominal drains by the 4th-5th day. Progressive oral tolerance was initiated the day after the NGT was withdrawn.

Postoperative pancreatic fistulas (POPF) were classified according to the ISGPF22 criteria, postoperative bleeding according to the ISGPF23 criteria, and DGE also according to the ISGPS24 criteria. Surgical complications were defined according to the Clavien classification,25 with grade > III being considered severe. In-patient mortality was defined as mortality that occurred during the hospitalisation.

Statistical analysisQualitative variables were expressed as the absolute value and their relative frequency as a percentage. The relationship between them was analysed by chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, depending on convenience. Qualitative variables were expressed as median and absolute percentiles (P0-P100). The relationship between qualitative variables was investigated using the Mann–Whitney U test.

All clinically relevant variables in the univariate analysis, especially those with p < .05, were taken using the binary logistic regression test to assess their influence on the presence of DGE grade C. Results were presented as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Survival analysis was run using the Kaplan–Meier curves and the log-rank test. A p < .05 value was considered statistically significant. For statistical analysis, SPSS Statistics, version 26 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) was used.

ResultsPreoperative characteristicsIn the comparison of preoperative variables such as age, sex, ASA, BMI, personal history and clinical symptoms, no statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups (PP-CPD and W-CPD), with the exception of duodenal obstruction, which was significantly more frequent in patients with W-CPD (p = .049). Regarding diagnostic imaging tests, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was performed with a significantly higher frequency in the PP-CPD group (p = .013). The size of the tumour detected by imaging tests was significantly larger in the W-CPD group (p = .017). In the comparison of bile duct calibre and Wirsung's duct, placement of a preoperative biliary stent, biopsy or preoperative cytology, there were no significant differences between the groups. In the comparison of laboratory parameters, only the median value of the CEA was significantly higher in the W-CPD group (p = .042), while there was no significant difference with respect to the value of CA 19/9 between the groups. Chemotherapy, which was given more frequently to patients in the W-CPD group, did not achieve any significant difference between the groups. (Table 1)

Preoperative patient characteristics.

| PP-CPDn = 124 | W-CPDn = 126 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 68 (16−87) | 66 (27−89) | |

| Sex (M/F) | 66/58(53.2%/46.8%) | 69/57(54.8%/45.2%) | .808 |

| ASA | .499 | ||

| I | 11 (8.9%) | 9 (7.1%) | |

| II | 54 (43.5%) | 53 (42.1%) | |

| III | 53 (42.7%) | 61 (48.4%) | |

| IV | 6 (4.8%) | 3 (2.4%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.7 (16−43.3) | 25.4 (14−42.7) | .193 |

| Personal Background | |||

| AHT | 54 (43.5%) | 55 (43.7%) | .987 |

| Cardiovascular | 45 (36.3%) | 44 (34.9%) | .599 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 30 (24.2%) | 35 (27.8%) | .388 |

| Respiratory pathology | 25 (20.2%) | 25 (19.8%) | .500 |

| Smoker | 23 (18.5%) | 31 (24.6%) | .077 |

| Tumour pathology | 21 (16.9%) | 16 (12.7%) | .346 |

| Drinker | 14 (11.3%) | 19 (15.1%) | .635 |

| Clinical symptoms | |||

| Jaundice | 80 (64.5%) | 75 (59.5%) | .416 |

| Weight loss | 58 (46.6%) | 66 (52.4%) | .375 |

| Abdominal pain | 54 (43.5%) | 52 (41.3%) | .715 |

| Cholangitis | 24 (19.4%) | 25 (19.8%) | .923 |

| Pancreatitis | 15 (12.1%) | 14(11.1%) | .808 |

| Upper gastrointestinal bleeding | 6 (4.8%) | 7 (5.6%) | .799 |

| Duodenal obstruction | 3 (2.4%) | 10 (7.9%) | .049 |

| Diagnostic tests. Findings | |||

| CT scan | 120 (96.8%) | 124 (98.4%) | .397 |

| NMR | 88 (71%) | 92 (73%) | .718 |

| Endoscopic ultrasound and biopsy | 75 (60.5%) | 77 (61.1%) | .919 |

| ERCP | 74 (59.7%) | 56 (44.4%) | .013 |

| TPHC | 15 (12.1%) | 16 (12.7%) | .885 |

| Tumour size (cm) | 2 (0.2−7.1) | 2.4 (0.2−6) | .017 |

| Bile duct size (cm) | 1.2 (0.4−3.1) | 1.2 (0.2−2.5) | .987 |

| Wirsung radiology | .973 | ||

| Dilated | 69 (55.6%) | 69 (54.8%) | |

| Normal | 55 (44.3%) | 57 (45.2%) | |

| Biliary prosthesis | .119 | ||

| No prosthesis | 62 (50%) | 77 (61.1%) | |

| Plastic | 39 (31.5%) | 38 (30.2%) | |

| Metal | 17 (13.7%) | 8(6.3%) | |

| Internal-external catheter | 6 (4.8%) | 3 (2.4%) | |

| Preoperative biopsy | 71 (57.7%) | 77 (61.1%) | .586 |

| Preoperative cytology | 21 (16.9%) | 20 (15.9%) | .821 |

| Laboratory | |||

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.7 (10.3−16) | 13.1 (9.1−17.2) | .415 |

| Platelets ×103 | 235 (80−431) | 236 (59−487) | .610 |

| INR | 1.02 (0.70−1.44) | 1.03 (0.87−1.47) | .967 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.77 (0.38−2.48) | 0.78 (0.43−1.9) | .343 |

| Blood sugar (mg/dL) | 104 (56−290) | 116 (72−304) | .482 |

| Na (mEq/L) | 140 (133−145) | 139 (132−145) | .972 |

| Albuminemia (g/dL) | 3.9 (2.6−4.8) | 3.9 (2.5−5.5) | .613 |

| Bilirrubinemia (mg/dL) | 2.5 (0.2−24.3) | 3.7 (0.2−28.9) | .899 |

| GGT (UI/L) | 51 (14−410) | 91 (12−1140) | .946 |

| GPT (UI/L) | 210 (8−2246) | 357 (10−1954) | .655 |

| GGT (UI/L) | 62 (10−791) | 145 (9−1682) | .143 |

| ALP (UI/L) | 275 (31−2262) | 272 (39−1909) | .444 |

| LDH (U/L) | 234 (116−602) | 269 (15−624) | .409 |

| CA 19/9 (U/mL) | 25.4 (3−13950) | 6.9 (17−6713) | .314 |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 2.3 (0−831) | 2.7 (0−48) | .042 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 11 (8.9%) | 18 (14.3%) | .181 |

ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; TPHC, transparietalhepatic cholangiography; AF, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, gamma glutamyl transferase; GOT, glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase; GPT: glutamic pyruvate transaminase; AHT, arterial hypertension; BMI, body mass index; LDH: lactodehydrogenase.

Time and transfusion were longer, although not statistically significant, with the W-CPD technique (380 vs. 402 min; p = .061). Pancreatic consistency was significantly softer in the W-CPD group and more frequently softer than normal in the PP-CPD group, although the difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.065). The Wirsung gauge, measured intraoperatively, was similar in both groups. Post-CPD reconstruction with a double loop was performed with a significantly higher frequency in the W-CPD group (p < .0001). Penrose drainage was used significantly more frequently in the W-CPD group (p < .0001). The histological type and degree of tumour differentiation were similar in both groups. Pancreatic and peripancreatic tumour invasion (T) was significantly more aggressive in the W-CPD group (p = .031), and the number of resected nodes was also significantly higher in the W-CPD group (p < .0001), although there were no significant differences between the groups in terms of nodal tumour invasion. No significant differences were observed between groups with respect to macro and microvascular and neural tumour invasion, R0 resection, vascular resection, and tumour staging. (Table 2)

Intraoperative and histological features.

| PP-CPDnp = 124 | W-CPD(n = 126) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery Time (min) | 380 (230−685) | 402 (190−645) | .061 |

| Blood transfusion | 18 (14.5%) | 22 (17.6%) | .284 |

| Consistency of pancreas | .065 | ||

| Hard | 55 (44.3%) | 59 (46.8%) | |

| Soft | 24 (19.3%) | 37 (29.4%) | |

| Normal | 45 (36.3%) | 30 (23.8%) | |

| Wirsung Calibre (intraoperative) | .799 | ||

| >3 mm | 64 (51.6%) | 66 (52.4%) | |

| <3 mm | 60 (48.4%) | 60 (47.6%) | |

| Type of reconstruction | <.0001 | ||

| Single loop | 118 (95.2%) | 87 (69%) | |

| Double loop | 6 (4.8%) | 39 (31%) | |

| Drainage | <.0001 | ||

| Jackson Pratt | 57 (45.9%) | 29 (23.1%) | |

| Penrose | 67 (54.1%) | 97 (76.9%) | |

| Histology | .144 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 76 (61.3%) | 96 (76.2%) | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 13 (10.5%) | 5 (3.9%) | |

| Neuroendocrine | 9 (7.2%) | 5 (3.9%) | |

| Other | 26 (20.9%) | 20 (15.9%) | |

| Degree of differentiation | .862 | ||

| Well differentiated | 30 (24.2%) | 28 (22.2%) | |

| Moderately differentiated | 45 (36.3%) | 54 (42.9%) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 18 (14.5%) | 23 (18.3%) | |

| Not assessable | 31 (25%) | 21 (16.7%) | |

| T Invasion | .031 | ||

| In situ | 4 (3.2%) | 2 (1.6%) | |

| <2 cm | 31 (25%) | 13 (10.3%) | |

| >2 cm (limited to the pancreas) | 37 (29.8%) | 41 (32.5%) | |

| Peripancreatic invasion | 32 (25.8%) | 50 (39.7%) | |

| CT or peri-SMA invasion | 3 (2.4%) | 4 (3.2%) | |

| Number of nodes resected | 13 (8−53) | 17 (8−78) | <.0001 |

| Lymph node invasion (N+) | 67 (54%) | 70 (55.6%) | .858 |

| Number of nodes + | 1 (1−12) | 1 (1−14) | .580 |

| Macrovascular invasion | 18 (14.5%) | 23 (18.3%) | .458 |

| Microvascular invasion | 52 (41.9%) | 42 (33.3%) | .202 |

| Neural invasion | 54 (43.5%) | 61 (48.4%) | .647 |

| R0 | 87 (70.2%) | 82 (65%) | .637 |

| Vascular resection | 11 (8.9%) | 13 (10.3%) | .698 |

| Tumour staging | .365 | ||

| IA | 19 (15.3%) | 8 (6.3%) | |

| IB | 10 (8.1%) | 13 (10.3%) | |

| IIA | 12 (9.7%) | 16 (12.7%) | |

| IIB | 34 (27.4%) | 39 (30.9%) | |

| III | 24 (19.3%) | 27 (21.4%) | |

| IV | 5 (4%) | 4 (3.2%) |

SMA: superior mesenteric artery; CT: celiac trunk.

With regard to postoperative morbidity and mortality (medical complications, POPF, haemorrhage, GVR, re-interventions, in-hospital mortality, complications as classified by Clavien–Dindo), ICU stay and hospital stay, no statistically significant differences were observed between the groups. During follow-up, no significant differences were observed between the groups as regards morbidity and mortality at 90 days (Table 3) and survival at 1, 3 and 5 years (Fig. 2). In the binary logistic regression analysis for DGE, it was observed that binary POPF B/C was a risk factor for the development of DGE C (p = .009). (Table 4)

Postoperative morbidity and mortality and survival.

| PP-CPDn = 124 | W-CPDn = 126 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Complications | 45 (36.3%) | 41 (32.5%) | .349 |

| Postoperative pancreatic fistula | .194 | ||

| Grade A | 20 (16.1%) | 29 (23%) | |

| Grade B | 13 (10.5%) | 21 (16.7%) | |

| Grade C | 8 (6.4%) | 8 (6.3%) | |

| No pancreatic fistula | 83 (66.9%) | 68 (53.9%) | |

| Postoperative haemorrhage | .950 | ||

| Grade A | 7 (5.6%) | 6(4.8%) | |

| Grade B | 6 (4.8%) | 8 (6.3%) | |

| Grade C | 6 (4.8%) | 6 (4.8%) | |

| No haemorrhage | 105 (84.7%) | 106(84.1%) | |

| Delayed gastric emptying | .423 | ||

| Grade A | 20 (16.1%) | 22 (17.5%) | |

| Grade B | 21 (17%) | 24 (19%) | |

| Grade C | 3 (2.4%) | 8 (6.4%) | |

| No delay in emptying | 80 (64.5%) | 72 (57.1%) | |

| Re-operations | 24 (19.4%) | 18 (14.3%) | .284 |

| Haemoperitoneum | 6 (4.8%) | 5 (3.9%) | |

| Pancreatic fistula | 8 (6.4%) | 8 (6.3%) | |

| Evisceration | 2 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Other | 8 (6.5%) | 5 (4%) | |

| Wound infection | 16 (12.9%) | 20 (15.9%) | .520 |

| Morbidity (Clavien–Dindo) | .360 | ||

| No complications | 40 (32.2%) | 29 (23%) | |

| Grade I-II | 53 (42.7%) | 66 (52.4%) | |

| Grade III-IV | 31 (25%) | 31 (24.6%) | |

| Hospital stay | 20 (7−60) | 20 (6−58) | .901 |

| In-hospital mortality (causes) | 3 (2.4%) | 5 (3.9%) | .583 |

| Septic shock | 1 (0.8%) | 2 (1.6%) | |

| Haemorrhagic shock | 2 (1.6%) | 2 (1.6%) | |

| ACVA | – | 1 (0.8%) | |

| Post-CPD follow-up (period) | 26 (0−141) | 31 (0−131) | .444 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 63 (50.8%) | 58 (46%) | .413 |

| De novo endocrine failure | 22 (17.7%) | 15 (11.5%) | .380 |

| De novo exocrine failure | 50 (40.3%) | 56 (44.4%) | .150 |

| Venous thrombosis | 7 (5.6%) | 5 (3.9%) | .470 |

| Pulmonary thromboembolism | 4 (3.2%) | 2 (1.6%) | .399 |

| Stroke | 3 (2.4%) | 3 (2.4%) | .943 |

| Morbidity (90 days) | 78 (62.9%) | 87 (69%) | .498 |

| Readmitted | 25 (20.2%) | 39 (30.9%) | .109 |

| Mortality (90 days) | 3 (2.4%) | 5 (3.9%) | .583 |

| Causes of mortality under follow-up | .592 | ||

| Tumour recurrence | 50 (40.3%) | 60 (47.6%) | |

| Cardiovascular | 2 (1.6%) | 1 (0.8%) | |

| Covid-19 | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (0.8% | |

| De novo tumour | – | 2 (1.6%) | |

| Unknown cause | 6 (4.8%) | 4 (3.2%) | |

| Survival | .491 | ||

| 1 year | 87.3% | 83.9% | |

| 3 years | 51.2% | 56.9% | |

| 5 years | 34.5% | 33.8% |

ACVA, acute cerebrovascular accident.

Binary logistic regression for delayed gastric emptying grade C.

| 95% C.I. for EXP(B) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sig. | CPD-Exp (B) | Inferior | Superior | |

| PP-CPD | .127 | .275 | .052 | 1.441 |

| Smoker | .597 | 1.337 | .456 | 3.923 |

| Duodenal obstruction | .340 | 2.637 | .360 | 19.322 |

| B/C POPF | .009 | 7.383 | 1.659 | 32.860 |

| Biliary prosthesis | .571 | .646 | .143 | 2.927 |

| Wirsung <3 mm | .320 | 2.430 | .423 | 13.951 |

Frequent homogeneity was observed with respect to the results of comparing preoperative variables between the PP-CPD and W-CPD groups in different series.13,17 This occurred in our study, with the exception of the significantly larger size of the tumour observed by radiological imaging (later confirmed by the pathologist), associated with the higher CEA level in the W-CPD group, which reflects the most advanced tumour stage, similar to what was recently published in another series with a significantly higher value of CA 19/9 and higher frequency of R1 in the W-CPD26 group.

PP-CPD may offer several advantages over W-CPD, such as a significant reduction in surgery time, intraoperative bleeding, and the need for blood transfusion.10,13,17,18,27 However, according to other authors,5,6,8 we have observed a longer surgery time, blood loss and need for transfusion in the W-CPD group, although without significant differences compared to the PP-CPD group.

One of the criticisms of the use of PP-CPD is the lower degree of oncological dissection and resection than that performed with W-CPD, with the consequent risk of tumour recurrence due to involvement of the duodenal section margin8,28 and a lower number of resected tumour lymphadenopathies. Another argument in favour of W-CPD is that it can be performed on all patients without fear of duodenal ischemia after CPD.8 In the present study, we have compared 2 groups with almost the same number of patients, performed according to the surgeons' preferences, conditions and tumour invasion. The size of the tumour and its degree of pancreatic and peri-pancreatic invasion was significantly larger in the W-CPD group. In addition, W-CPD enabled us to perform lymph node excision of a significantly larger number of nodes, although their tumour positivity was similar in both groups. The higher, but not significant, rates of macrovascular and perineural invasion and vascular resection, along with tumour staging, give us more information about the greater degree of tumour invasion in the W-CPD group compared to the PP-CPD group.

In both our experience and in the data reported in the literature, it was observed that there were no significant differences in the comparison of patients operated on by PP-CPD and W-CPD with respect to the rates of post-CPD fistulas (biliary, POPF and gastrointestinal),6,8,10,11,17,18 postoperative morbidity according to Clavien–Dindo,17 reinterventions,6,8,18 surgical wound infection,8,10,17,26 hospital stay6,10,13,18,26 and readmissions.26 In addition, we agree with other studies regarding the similarity of R0 resection and in-patient mortality rates in the case of both techniques.8,10,11,13,26

We analysed DGE in both groups of patients due to its high post-CPD incidence and association with prolonged hospital stay. DGE is defined as the inability to return to a normal diet at the end of the first week post-CPD. along with the need to maintain the nasogastric tube.24 The pathogenesis of post-CPD DGE is unclear, this being attributed to multiple causes, including those related to surgery, such as duodenal resection resulting in the absence of gastrointestinal hormones,5 antroduodenal ischemia due to pyloric artery section,29 duodenal congestion due to left gastric vein section,30 pyloric spasm due to vagus nerve section17,31 and surgical complications (POPF, intra-abdominal abscesses, or haemorrhage).32

The overall incidence of DGE in comparative series between PP-CPD and W-CPD is reported to be between 10.8 and 50%, 17–61.5% corresponding to PP-CPD and between 21–50% to W-CPD.6,8,10,14–17,19 A significantly higher incidence of DGE was found with PP-CPD in 5 of these series.10,14–17 In the present study, the overall incidence of DGE was 39.2%; higher, although not significantly. In the W-CPD group compared to the PP-CPD group (42.8% vs. 35.5%), which was similar to other published series.6,19 In the binary logistic regression analysis for DGE, it was observed that binary B/C POPF, but not PP-CPD, was the only risk factor for the development of DGE, as other authors have already pointed out.17,33–38 The fact that relevant B/C POPF has been demonstrated as a risk factor for DGE was not correlated with a statistically significant difference in DGE between PP-CPD and W-CPD.17

We did not observe significant differences in relation to the incidence of morbidity and mortality at 90 days, with the causes of mortality being mainly due to tumour recurrence, as published by other authors.26 As in our series, other surgeons show similar long-term survival rates in patients operated on with both techniques.5,8,10,11,13

A better quality of life and nutritional status have been observed with the performance of a PP-CPD,27,39 and some anthropometric measures may also indicate better recovery for the patient.8 Similar quality of life and nutritional status have also been demonstrated in several series with both techniques.8,13,14,40 During long-term follow-up, we did not detect significant differences between the groups in relation to endocrine and exocrine function of the pancreas, tumour recurrence, and readmission rate. However, a recent publication has shown that W-CPD is associated with a significantly higher incidence of non-alcoholic hepatic steatosis.41

Finally, there is no clear agreement regarding the most suitable technique to use, since surgeons opt for one or the other technique depending on the lower incidence of DGE in W-CPD,8,14,17 or the lower incidence of haemorrhage, intraoperative transfusion and operating time in PP-CPD,6,18,20 since the remainder of the postoperative complications, mortality, postoperative stay, and long-term survival are similar for both techniques.6,8,14,17,20 Other surgeons generally prescribe PP-CPD on the grounds that there are no convincing reasons to sacrifice the pylorus, except in patients with a tumour close to the first duodenal portion or ischaemia of the latter, in which case a W-CPD should be performed.26,39

As a limitation of this study, we should point out its retrospective nature, with the consequent bias in data collection, the CPD performed by several different surgeons, the use of 2 intestinal loops in 45 cases, the long duration of inclusion, the preoperative differences between the 2 groups of patients and the characteristics of the tumours, and lastly, their degree of invasiveness.

Conclusions. Postoperative morbidity and mortality and long-term survival were not significantly different between PP-CPD and W-CPD, however binary B/C POPF was a risk factor for DGE. Therefore, both techniques can be used interchangeably, also taking into account the safety margins of the tumour in its proximity to the duodenum.

Funding sourcesThis research has not received any specific support from public sector agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit organisations.

Conflict of interestNone.

Manuscript submission and verification statementsThis study is not under evaluation for publication in any other medium, it is authorised by all authors and by the competent authorities of our institution (Research Institute). If the study is accepted, it will not be published in any other medium in the same format, in English or in any other language, or in electronic format without prior written consent of the copyright holder.

AuthorshipIago Justo Alonso: study design, drafting of the article, critical review and approval of the final review.

Alberto Marcacuzco Quinto: study design and data acquisition and collection.

Óscar Caso Maestro: acquisition and collection of data; analysis and interpretation of results.

Laura Alonso Murillo: acquisition and collection of data; analysis and interpretation of results.

Paula Rioja Conde: acquisition and collection of data; approval of the final review.

Clara Fernández Fernández: acquisition and collection of data.

Carlos Jiménez Romero: study design, drafting of the article, critical review and approval of the final review.