This article aims to gain a better understanding of the relationship between economic recession and entrepreneurship. The process of entrepreneurship, rather than the action itself, is a complex phenomenon, and such complexity surfaces when local context conditions worsen after an economic recession. This paper addresses the issue of how the likelihood of individuals to engage in the creation of new firms is affected by a recessionary climate. Furthermore, the study focuses on how the recession-driven shake-out effect varies across local contexts (i.e., sub-national regions). The case of Spain in the critical period of 2007–2010 is examined by using multilevel logistic mediation models on individual-level and sub-national region-level panel data. The results show that entrepreneurship shrinks during economic downturns, suggesting a pro-cyclical trend. A weaker perception by individuals of business opportunities resulting from the shake-out explains, to a large extent, the lower propensity to create firms during economic recession.

In recent years, world economies have witnessed one of the most severe economic recessions since the Great Depression of the 1930s (IMF, 2009; Parker, 2012; Shane, 2011; World Bank, 2009). Peripheral countries of Europe, such as Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, and Spain, have been some of the most affected economies after the 2007–2009 financial crisis. A rise in the unemployment rate, limited access to financing, and a decline in the growth of gross domestic product (GDP) are noticeable consequences of this economic recession (Papaoikonomou et al., 2012; Mishkin, 2011). Although entrepreneurial activity is seen as an engine of growth, it is not exempt from shake-out effects of economic downturns (Congregado et al., 2012; Rampini, 2004). However, beyond the main macroeconomic indicators, how does a global crisis affect the process of entrepreneurship?

Most scholars agree that understanding the relationship between economic cycles and entrepreneurship is important for policy intervention in order to predict and generate more favourable conditions for firm creation (Fairlie, 2013; Koellinger and Thurik, 2012; Ghatak et al., 2007). However, this relationship warrants further research as the entrepreneurship literature provides mixed results on the effect of business cycles on business start-up rates (Parker, 2011). Moreover, little is known about the effect of sudden shocks in the economy on different stages of the entrepreneurial process (Simón-Moya et al., 2014; Santos et al., 2017). The vast majority of previous studies has analyzed such impacts by focusing on the entrepreneurial activity as an outcome (i.e., the action of creating a firm) rather than on the process itself (i.e., a continuum of steps from opportunity recognition to firm creation). Indeed, a large bulk of studies has examined such relationships at the country level. Only a few studies have emphasized the effect of a shock on the inner territories of a given country (e.g., Bishop and Shilcof, 2017; Williams and Vorley, 2014). We believe that such an impact is manifested in different forms and different levels of intensity across sub-national regions. Not all the local regions suffer the consequences of the crisis in the same manner (i.e., because local territories are naturally, physically, financially and intangibly differently endowed), neither they need one same national policy to recover from it. In fact, the entrepreneurial activity varies substantially across NUT-2 regions in Spain (González-Pernía et al., 2012). Therefore, we expect that the influence of a recession-driven economic shock on the process of entrepreneurship will be different across local contexts inside a country.

Following cognitive and planned behaviour theories of the mid 1990s, entrepreneurship can be conceived as a process involving both the opportunity perception and the subsequent action to create a new firm. An emerging research stream raised the issue of why some individuals, and not others, explore and exploit entrepreneurial opportunities. Well-known scholars emphasized the idea that entrepreneurial actions are preceded by intuition and opportunity perception (Krueger, 1993; Mitchell et al, 2002). In turbulent periods, sporadic shocks in the business cycle affect not only labor markets, but also the decisions of individuals to start up new firms (Audretsch and Acs, 1994; Highfield and Smiley, 1987). These decisions can be altered by how individuals perceive opportunities to create a new firm in a non-favourable context. In this vein, business cycle theorists hold that economic shocks can produce an ambiguous effect (Parker, 2011; Fairlie, 2013). Such shocks may allow individuals to detect and exploit new entrepreneurial opportunities prompted originally during a new recessionary context, or alternatively, economic shake-outs can discourage the detection and pursuit of new business opportunities due to pessimistic growth expectations of (would-be) entrepreneurs.

In this paper, we claim that the economic crisis affects not only the capacity of individuals to start up new firms but also their desire, ability, need and motivation to identify and exploit new business opportunities. Presumably, the response of the whole entrepreneurial process to a recessionary economic shock (i.e., the process starting from opportunity perception and leading to the action of creating a new firm) should be heterogeneous across more or less economically advanced sub-national regions. Thus, the main objective of this paper is to provide new insights on how a recession-driven economic shake-out affects the entrepreneurial process (besides the action) at a sub-national context.

We expect to make a modest contribution by shedding light into the subject of economic recession and entrepreneurship. Furthermore, we aim at empirically testing main notions of planned behaviour and business cycle theories, by focussing on the analysis of the entrepreneurial process. We expect to contribute to the abovementioned fields of entrepreneurship in several ways. First, we study a pioneering subject by unravelling the missing link between the shakeout effect of an economic downturn and entrepreneurial action, by focussing on why and how the business opportunity perception of individuals mediates this effect. We further argue that as entrepreneurial action follows intention, at an earlier stage economic shake-out shapes opportunity perception. As a matter of fact, we merge business cycle and planned behaviour notions to propose (and test) that the advent of a severe crisis affects business intentions, which ultimately, determines entrepreneurial action (i.e., firm creation). Second, unlike other studies we analyse the shakeout effect on the entrepreneurial process at a sub-national level, since we expect such an impact to be unequal within a country. With this fine-grained analysis, a more precise academic understanding, and insights for policy making, are provided on how an economic shake-out differently affects entrepreneurship in wide-ranging local contexts. Third, we apply a scarcely used multilevel logistic regression method to panel data, complemented with mediation tests, to verify our novel propositions. A large and representative database is used consisting of two-level data, (i.e., individual-level information and NUTS-2 region-level data) collected from a diverse array of primary and secondary data sources. Finally, our findings provide useful guidance to policymakers for the design of local entrepreneurship programs better suited to economic turmoil.

The structure of the paper is as follows. The next section outlines the theoretical background explaining the link between the recession shakeout effect and the process of entrepreneurship and proposes the hypotheses of the study. The third section describes the methodology and data, and the fourth section summarizes the results. Finally, the study ends with our main conclusions and implications.

The missing link between an economic recession-driven shakeout effect and the process of entrepreneurshipAn economy-wide shock is a sudden, substantial and unanticipated change in the macroeconomic context. Typically, an economic shock is characterized by a significant decline in the aggregate demand which, in turn, hurts consumer and investor confidence (Mishkin, 2006; Suarez and Oliva, 2005). A sudden shock may also weaken the self-confidence of potential entrepreneurs to engage in firm creation because business opportunities vanish or simply because such opportunities are disregarded and ignored. During an economic downturn, both entrant and incumbent firms face several obstacles: reduced access to credit and financial markets, a disruption of supply goods and services, and increasing uncertainty about the recovery. However, unemployment rises as a result of the closure of less competitive firms, and entrepreneurship turns into a valued self-employment choice for a substantial share of jobless people.

There is a broad consensus in the literature on the fact that individual-level characteristics alone do not fully explain entrepreneurial action. Context matters for understanding why, when and how individuals get involved in the entrepreneurship and firm formation processes (Fuentelsaz et al., 2015; González-Pernía et al., 2015; Welter, 2011). Sound theoretical arguments and empirical evidence suggest that entrepreneurship is predominantly a ``regional event’’ since major contextual factors shaping entrepreneurial behavior operate at a lower scale regional level (Feldman, 2001; Sternberg and Rocha, 2007). Although the recent economic recession is considered to be a global phenomenon, its impact varies not only across countries but also across sub-national regions.1

The effect of spatial economic contexts on entrepreneurial activity has been documented since the early 1990s (Reynolds et al., 1994; Acs and Storey, 2004; Bosma et al., 2008; Fritsch, 2008; Audretsch and Peña-Legazkue, 2011; Acs et al., 2015; Bishop and Shilcof, 2017). Past findings show that the rate of new firm start-ups is influenced by a bundle of macroeconomic conditions (such as the level of economic growth, the unemployment rate, the aggregated demand, etc.), and therefore, the entrepreneurial activity is sensitive to changes in GDP per capita, unemployment rates and interest rates (Congregado et al., 2012; Fritsch et al., 2015; Koellinger and Thurik, 2012). Moreover, macroeconomic fluctuations influence expectations and market opportunities to start up new firms (Reynolds, 1994; Reynolds et al., 2002).2

An emergent research stream on the theory on business cycles and entrepreneurship offers two unclear predictions about how individual and firm behaviors are affected during economic recessions: a pro-cyclical prediction and a counter-cyclical prediction. In the first case, entrepreneurial behavior and entrepreneurial activity are negatively affected by the impact of a recessionary environment (i.e., pro-cyclical trend). Under this lens, business opportunities vanish as a consequence of the drop in demand for goods and services. In the second case, the entrepreneurial activity is positively influenced by a recessionary environment (i.e., counter-cyclical prediction). A shrinking market reduces job opportunities, which pushes individuals to start a business for subsistence. Overall, findings provide mixed results about the relationship between the economic context and entrepreneurship.

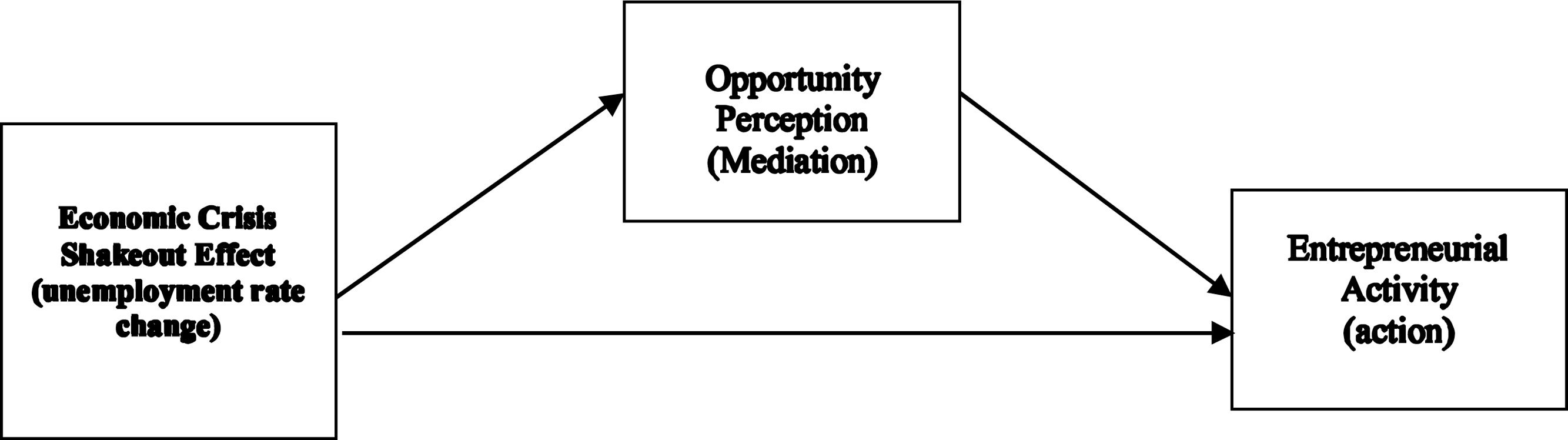

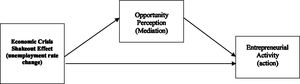

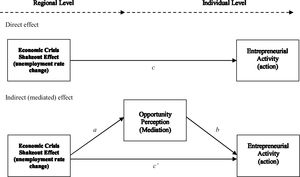

Entrepreneurship is understood as a process where opportunities are perceived, and actions are undertaken to exploit such opportunities via business formation (Vegetti and Adăscăliţei, 2017). To contribute to this ongoing academic debate and following the work by Stuetzer et al. (2014), we argue that the missing link between the impact of the economic crisis shakeout and the process of entrepreneurship can be explained by the influence of unemployment rate changes on entrepreneurial action (i.e., firm creation) mediated by changes on individual opportunity perception across heterogeneous sub-national spatial contexts (see Fig. 1).

In this paper, we hold that entrepreneurial perceptions and actions vary across sub-national contexts. Following an “entrepreneurial action” view, several studies show the existence of a direct negative effect exerted by an economic crisis on entrepreneurial activity (Vegetti and Adăscăliţei, 2017). We complement this view, and unlike other studies, we adopt an “entrepreneurial process” perspective. For simplicity, we differentiate two stages of this continuum: a first stage where the economic recession presumably leads to a low opportunity perception, and a second stage where a weaker opportunity perception results in a reduced entrepreneurial activity. On the whole, we argue that an economic shake-out exerts an indirect negative effect on entrepreneurial activity mediated by a lower opportunity perception of opportunities at an earlier discovery phase (Shane and Venkataraman, 2000). For our empirical analysis, we run a mediation test by considering both the direct and indirect effects.

The “entrepreneurial action” view: a one-stage direct effectIndividuals create firms in distinct contexts with different motivations. Indeed, a higher unemployment rate may lead to increased or decreased entrepreneurial activity (Parker, 2011). Unemployed individuals are more likely to create a firm when the opportunity cost of earning an employee-wage is lower than the income earned from entrepreneurship (and/or when there is also a low switching cost from being employed to becoming an entrepreneur). When higher unemployment rates are positively associated with new firm formation rates, the unemployment-entrepreneurship positive linkage reflects a countercyclical pattern (Carree et al., 2002; Simón-Moya et al., 2016; Storey, 1991).

An alternative argument suggests that a high level of unemployment mirrors a contraction of market demand. A more pessimistic expectation of individuals about obtaining firm profits during a recession would discourage the creation of start-ups (Audretsch and Fritsch, 1994; Storey and Johnson, 1987). In this case, the unemployment-entrepreneurship negative relationship would describe a pro-cyclical trend (Acs and Armington, 2004; Armington and Acs, 2002; Carrasco, 1999). The incipient business-cycle entrepreneurship theory needs further refinement, and more empirical evidence, to gain an overarching understanding of this phenomenon and to accomplish a more accurate prediction capacity (Parker, 2011).

In a recent study, Koellinger and Thurik (2012) showed the existence of a pro-cyclical trend in their study conducted on 23 OECD countries for the period of 1972–2007. Similarly, Shane (2011) found that during the 2007–2009 recession, the United States had fewer businesses and self-employed people than before the economic downturn. Other findings also suggest that a pro-cyclical trend of entrepreneurship in a recessionary period reflects a higher risk perception of individuals for business creation (Ghatak et al., 2007; Koellinger and Thurik, 2012; Parker et al., 2012). Like in most empirical studies on this issue, we also believe that entrepreneurship is vulnerable to business cycles, and therefore, firm creation decreases in periods of economic downturns. This is largely due to the fact that unfavourable context conditions discourage new firm creation.

Nevertheless, we do not expect this effect to be the same across all sub-national contexts. Territories at sub-national level are diverse, markets work differently, and resource mobility is difficult for high switching costs. Studies conducted at the country level suggest that poorer countries generally exhibit higher entrepreneurial rates than richer countries (Reynolds et al., 2002). Therefore, developing territories are associated with higher levels of necessity-driven entrepreneurs, whereas more developed regions evince higher levels of opportunity-driven business start-ups. Simón-Moya et al. (2016) confirm these results and conclude that entrepreneurial activity is greater in contexts with lower levels of development, greater income inequality and considerable levels of unemployment. At the same time, they found that necessity-driven entrepreneurship plays a more prevalent role in these locations. In a similar vein, other findings from more developed economies, such as the U.S. and Germany, demonstrate that opportunity-driven entrepreneurship shows a pro-cyclical trend, whereas necessity-driven entrepreneurship shows a stronger counter-cyclical trend (Fairlie and Fossen, 2018). However, we lack evidence on how these results unfold at a local context level.

A recent study by Santos et al. (2017) on the impact of the economic crisis on entrepreneurship in Europe reveals that prior to the outbreak of the economic crisis (i.e., year 2008), lower-income Southern countries of Europe (i.e., Spain, Portugal and Greece) had a higher entrepreneurial activity than that of their Nordic counterparts (i.e., Sweden, Norway and Finland). However, after year 2008 the trend reversed. Nordic regions were more likely to engage in entrepreneurship than Southern Europe during recession. Vegetti and Adăscăliţei (2017) provide an explanation to this phenomenon arguing that the decrease in entrepreneurial action has been more pronounced in European territories where access to finance has been more difficult (i.e., Southern EU contexts). In other words, in EU regions where would-be entrepreneurs faced better borrowing and consumer demand conditions (i.e., higher-income locations like the Nordic countries), the recession did not have a significant negative effect on entrepreneurial action. A similar phenomenon can be observed in Spain for the same period. In general, entrepreneurial activity has declined in recent years. Poorer sub-national regions faced the highest entrepreneurial activity right at pre- recession, but during the second decade of the current century this tendency has been inverted. According to the Spanish Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) report (Peña et al., 2018), sub-national territories with higher GDP per capita in Spain show now a higher entrepreneurial activity at post-recession, than their lower-income counterparts. For instance, a more favourable and advantageous economic context of places like Madrid and Catalonia has slowed down the declining trend of entrepreneurship. Moreover, Spanish GEM data also show that there is a gap between low and high income sub-national territories in terms of the prevalence of informal investors for start-ups. Considering these compelling arguments and the empirical evidence associated to them, likewise we posit that the direct effect of the shake-out on the entrepreneurial action is expected to be negative, and it will be more severe in lower-income than in higher-income sub-national regions of Spain.H1a A recession-driven economic shakeout (i.e., a higher unemployment rate) affects negatively the direct “action” of firm creation. A recession-driven economic shakeout negative direct effect on entrepreneurial “action” is stronger in lower-income than in higher-income sub-national regions.

Entrepreneurial actions refer to factual behavior in response to a judgmental decision under uncertainty about a possible opportunity for profit (Hastie, 2001). Cognitive theories of entrepreneurship hold that individual perception of entrepreneurial opportunities is a central motivating factor that triggers entrepreneurial behavior and action (Camelo-Ordaz et al., 2016; McMullen and Shepherd, 2006). The identification and pursuit of entrepreneurial opportunities represent a chance for an individual to generate economic value by creating a new firm. Therefore, entrepreneurial action could be considered an extension of perceived opportunities (Lee and Venkataraman, 2006; McMullen and Shepherd, 2006). That is, entrepreneurial action is a subsequent stage that follows the early stage of opportunity discovery and the exploitation of the business idea.

By adopting an entrepreneurial process view, we separate the opportunity perception phase from the business creation (action) phase. Both stages reflect the two basic steps of the Ajzenian planned behaviour theory and both phases together emphasize the potential and the actual realization of entrepreneurship (Vegetti and Adăscăliţei, 2017).

Entrepreneurs take a step forward onto a later stage consisting on the action of creating a new firm, when they are confident about their own skills, motivated and with a strong desire (or need) for self-employment. At early stages of this continuum, entrepreneurs explore and exploit opportunities when they have greater expected values associated with the following: (i) the industry’s characteristics (e.g., higher profit margins, large expected demand); (ii) the macroeconomic conditions that also influence their expected values (e.g., economic growth, lower unemployment, low cost of capital); (iii) and access to suitable resources (Nabi and Liñán, 2013; O’Brien et al., 2003; Stuetzer et al., 2014). Therefore, in recessionary periods, the probability that individuals perceive opportunities resulting in entrepreneurial action is also related to their perception about contextual factors that dampen (or boost) entrepreneurship (Papaoikonomou et al., 2012; Williams and Vorley, 2015).

Several studies hold that a higher unemployment rate is understood as a negative determinant of individuals’ opportunity perception (Audretsch and Thurik, 2001; Evans and Leighton, 1990; Ghatak et al., 2007; Koellinger and Thurik, 2012; Shane, 2011). Individuals face different occupation alternatives: self-employment, waged-employment and unemployment (Knight, 1921). Under the premises of cognitive and planed behaviour theory, the choice of self-employment depends, to a large extent, on opportunity perception (Santos et al., 2017).

Following an entrepreneurial process perspective and blending together its two phases (i.e., entrepreneurial opportunity perception and entrepreneurial action), we can approximate the indirect effect of the economic shake-out on business creation via opportunity perception. On the one hand, an economic downturn is expected to undermine entrepreneurial opportunity recognition, and on the other hand, a weaker business opportunity perception will turn into a lower entrepreneurial activity. By combining these two stages in our broader entrepreneurial process framework (i.e., like in the study by Stuetzer et al., 2014), we argue that the linkage between an economic shock (i.e., a rapid rise of unemployment) and entrepreneurial action is mediated by the ability of entrepreneurs to identify business opportunities.H2a A recession-driven economic shakeout (i.e., a higher unemployment rate) affects negatively the early phase of opportunity perception. The perception of a business opportunity positively affects the action of creating a new firm, so that a lower entrepreneurial opportunity perception will lead to a lower entrepreneurial action. Opportunity perceptions exert an indirect (mediating) effect on the relationship between a recession-driven economic shake-out (i.e., unemployment rate change) and entrepreneurial action (i.e., firm creation).

The dataset includes both individual-level and NUTS-2 region-level data from Spain over the period of 2007–2010. The case of Spain is suitable for the analysis of the current economic crisis at a sub-national context for two reasons. First, the country has profoundly suffered the consequences of the last economic crisis with a recession that has been characterized by an unprecedented rise in unemployment. According to official statistical sources, the INE (Instituto Nacional de Estadística) reported that the number of newly created firms dropped from 410,975 new firms created in 2008 to 321,180 in 2010; moreover, the stock of active firms in Spain fell from 3,422,239 to 3,291,263 firms during the same period. Second, Spanish sub-national regions differ in terms of their level of economic development (i.e., GDP per capita at the NUTS-2 level regions). The time span of our study includes two periods: the period before and the period immediately after year 2008 (i.e., the year in which the shake-out started to occur). The selection of this period allows us to compare our findings with those obtained by other recent studies (Carreira and Teixeira, 2016; Fairlie, 2013; Foster et al., 2016; Nabi and Liñán, 2013; Santos et al., 2017; Simón-Moya et al., 2014; Vegetti and Adăscăliţei, 2017).

Data on individual variables come from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) project, an international research program focused on entrepreneurship that has annually conducted a standardized survey in more than seventy countries since the end of the last century (see Reynolds et al., 2005 for more details). Similar to the study by Camelo-Ordaz et al. (2016), we used GEM data from Spain to analyze the effect of individual-level variables. The information was complemented with data at the regional level from the Spanish National Institute of Statistics (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, INE by its Spanish acronym). Our final sample consisted of 51,314 individuals interviewed (via the GEM survey) and living in one of the 17 regions of Spain (at the NUTS-2 level representing the territories of Comunidades Autónomas) during the 2007–2010 period.

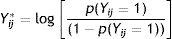

Description of variablesThe dependent variable (Entrepreneurial_Action) is a dummy variable created from GEM data that measures whether or not an individual has been identified as a nascent entrepreneur; that is, an individual who has undertaken actions in the last year to create a new business in which he or she expects to have ownership and has not been paying wages for more than 3 months (Reynolds et al., 2005). This variable is to test the direct effect and it takes the value 1 (one) when the individual is considered a nascent entrepreneur and is 0 (zero) otherwise. Thus, nascent entrepreneurs are compared to respondents who are not engaged in firm creation at all.

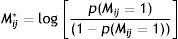

To test the indirect effect, our mediator variable (Opportunity_Perception) is a dummy that measures whether or not the interviewed individual perceives that there will be good opportunities for starting a local business in the next six months where the respondent lives. Data on opportunity perceptions are taken from the GEM project. The variable takes the value 1 (one) if the respondent perceives good opportunities and is 0 (zero) otherwise.

The main explanatory variable representing the recession-driven economic shock is represented widely in the literature by the change in unemployment rate (ΔUnemployment), and it describes changes in the local economic context derived from the shake-out. Data for this lagged variable have been taken from the Spanish Institute of Statistics and correspond to the annual percentage change in the total unemployment rate with respect to the previous year (for sub-national regions at the NUTS-2 level).

A set of control variables at both the individual-level and the region-level was also added to our model. The control variables at the individual-level were categorical variables indicating demographic, human capital-related and perceptual variables. These have been widely used in the entrepreneurship literature (Arenius and Minniti, 2005; Guerrero and Peña-Legazkue, 2013; Lévesque and Minniti, 2006; Jimenez et al, 2015; Mickiewicz et al, 2017; Minniti and Naudé, 2010; Santos et al, 2017; Vegetti and Adăscăliţei, 2017). In fact, GEM surveys capture basic information on the profile of individuals, such as their risk attitude, income, education, gender or age (Bosma, 2013). We included as control variables age and gender of respondents. We segmented them by age groups (Age) and expect a positive association for the younger groups and a negative one for the older respondents. This is in line with empirical findings that usually show a negative association with ‘entrepreneurial action’ meaning that younger individuals are more likely to start a business than older ones (Vegetti and Adăscăliţei, 2017; Santos et al, 2017; Lévesque and Minniti, 2006; Arenius and Minniti, 2005). For gender (Male) we included a dummy variable, taking value 1 if the respondent is male and 0 if female. According to extant literature we expect a positive association with the dependent variables (Vegetti and Adăscăliţei, 2017; Santos et al, 2017; Arenius and Minniti, 2005; Minniti and Naudé, 2010). Regarding the origin of the entrepreneur (Inmigrant), we included a variable that takes value 1 if the respondent is an immigrant and 0 otherwise. As in several studies, we expect a positive association with the dependent variables (Mickiewicz et al, 2017). We included also variables accounting for income and educational level. High_Income is a dummy taking value 1 if the respondent’s income level is in the top third and 0 otherwise. High income level reduces financial barriers and increases the likelihood of starting a new business (Arenius and Minniti, 2005). University_Education is a dichotomous variable indicating whether the individual holds a university degree. Education is associated with the likelihood of starting a new business (Vegetti and Adăscăliţei, 2017; Jimenez et al, 2015; Arenius and Minniti, 2005), and with the perception of new business opportunities. We considered start-up investment and firm creation experience (Investor_Experience and Entrepreneurial_Experience) expecting both to be positively associated with the dependent variables (Guerrero and Peña-Legazkue, 2013). We included also dummies accounting for risk perception, entrepreneurial skills and entrepreneurial exposure, expecting a positive association with the dependent variables (Santos et al, 2017; Guerrero and Peña-Legazkue, 2013; Arenius and Minniti, 2005). No_Fear_of_Failure indicates whether or not the individual considers that fear of failure would prevent him or her from starting a business. Entrepreneurial_Skills is a dummy variable indicating whether or not the respondent considers he or she has the knowledge, skills and experience required to start a business. Entrepreneurial_exposure indicates whether or not the interviewed individual knows someone who has started a business in the past two years. Data for all control variables at the individual level came from the GEM-Spain project.

We also have added context-level control variables for sub-national regions to reflect other contextual proxies beyond the shake-out effect. Given the purpose of the study, we considered the unemployment rate (Unemployment) as in Fuentelsaz et al (2015) or Vegetti and Adăscăliţei (2017). We also included population density (Population_Density), the stock of firms per thousand inhabitants (Firm_Stock), the percentage of total unemployment in manufacturing (Manufacturing_Unemployment), and the percentage of total unemployment in construction (Construction_Unemployment). Data for all control variables at the region-level are publicly available from the Spanish Institute of Statistics’ website.

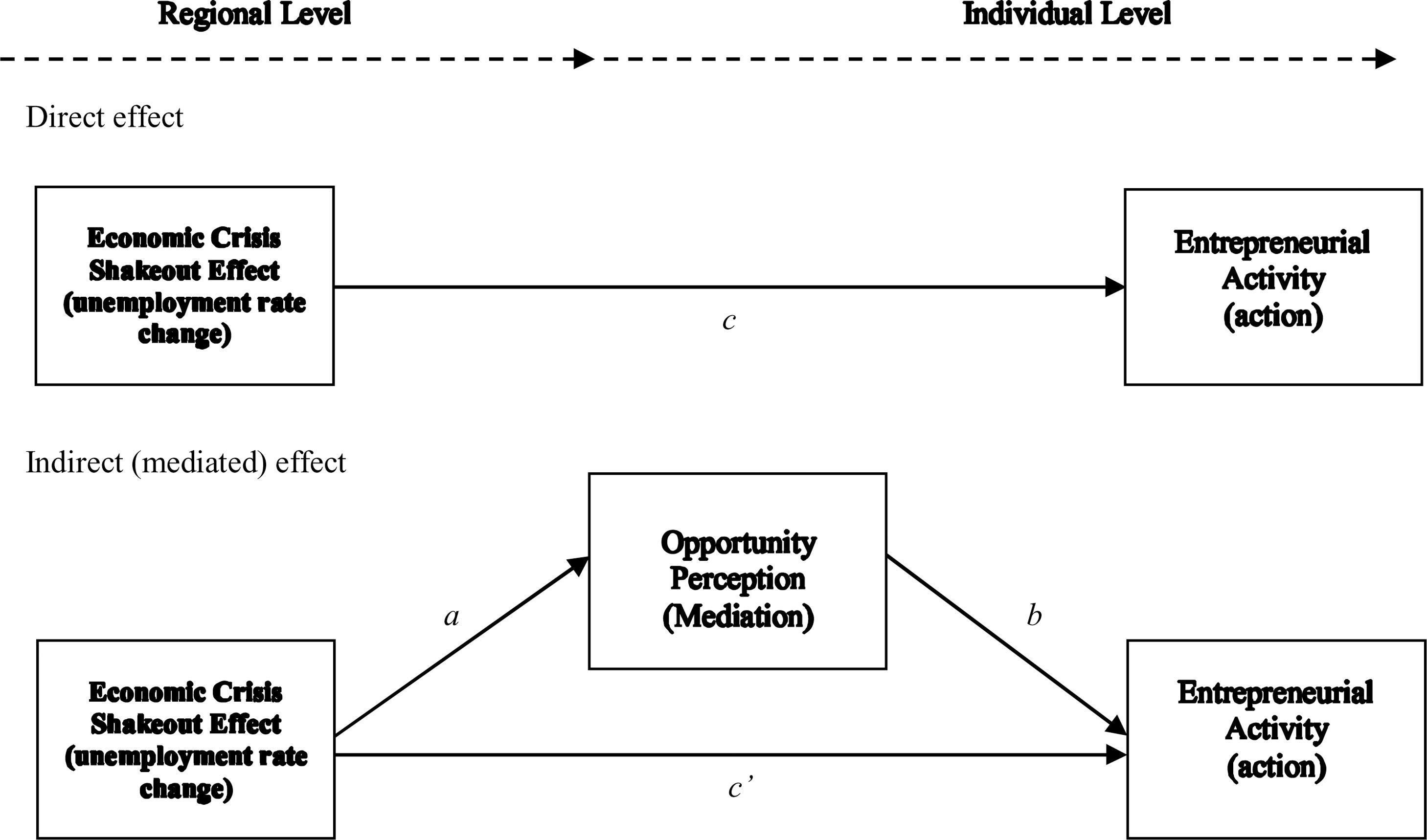

Empirical modelA multi-level analysis was conducted to analyze the impact of the recent recessionary economic period on nascent entrepreneurial activity. More specifically, we examined the impact of the change in the unemployment rate at the region-level on the propensity of individuals to engage in nascent entrepreneurial activity. According to our reasoning, this entrepreneurial process is represented by a relationship mediated through the opportunity perception at the individual-level. The empirical analysis consists of a multilevel mediation model (MacKinnon, 2008) in which the explanatory variable (X) is at the region-level, and the mediator (M) and dependent variable (Y) are at the individual-level (see Fig. 2).

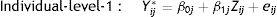

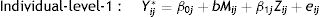

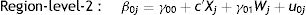

The multilevel mediation model is represented by three systems of equations:

The individual-level-1 part of Eq. (1) includes the dependent variable, Yij*,

which is the probability of the ith individual in the jth region being a nascent entrepreneur who has undertaken actions in the very early stage of the entrepreneurial process; β0j is a region-level intercept; Zij is a vector of individual-level control variables; β1j is the effect of such variables; and eij is the individual error term, which is assumed to be logistic-distributed with a mean of zero and constant variance of π2/3.The region-level-2 part of Eq. (1) indicates that the region-level intercept, β0j, is equal to the overall mean, γ00, plus the coefficient c that refers to the direct effect of Xj, the explanatory variable at the region-level; the coefficient γ01 that refers to the effect of Wj, a vector of region-level control variables, and u0j, which is a random effect that captures the deviations of the predicted region-level mean from the observed region-level mean.

In Eq. (2), the individual-level-1 part includes the coefficient b that refers to the effect of the mediator variable, Mij, while the region-level-2 part includes the coefficient c′ that refers to effect of the independent variable, Xj, adjusted for the effect of the mediator. The rest of the parameters in both the individual-level 1 part and the region-level part are similar to those of Eq. (1). Finally, the individual-level-1 part in Eq. (3) includes the dependent variable, Mij*,

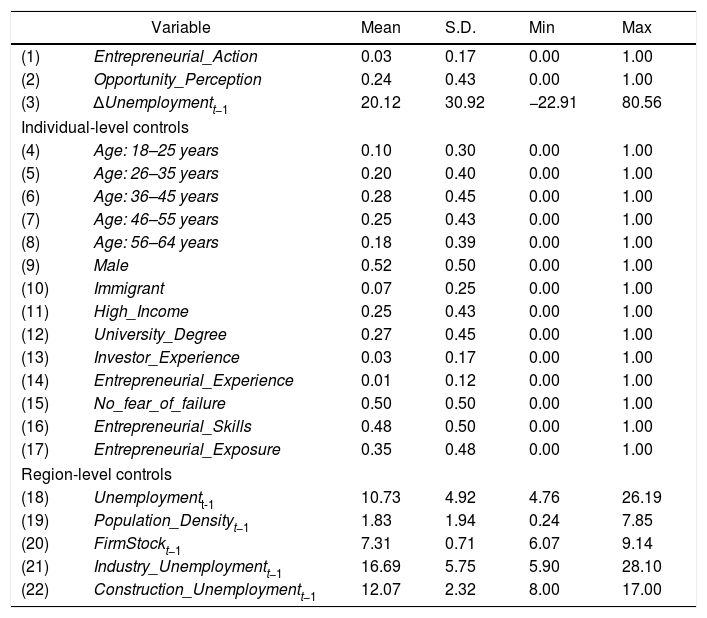

which is the probability of the ith individual in the jth region perceiving entrepreneurial opportunities. In contrast, the region-level 2 part includes the coefficient a, which refers to the effect of the independent variable, Xj. As in Eq. (2), the rest of the parameters in both the individual-level 1 part and the region-level part are similar to those of Eq. (1).Descriptive statisticsTable 1 shows the descriptive statistics, while Table 2 illustrates the correlation matrix for the whole sample during the period of 2007–2010. As exhibited in Table 1, approximately 24% of individuals perceive business opportunities in the next six months and 3% of the individuals are engaged in a nascent entrepreneurial activity. These figures are similar to those of other European countries obtained by Santos et al. (2017) for the period of the economic crisis in the EU.

Descriptive statistics.

| Variable | Mean | S.D. | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | Entrepreneurial_Action | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| (2) | Opportunity_Perception | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| (3) | ΔUnemploymentt−1 | 20.12 | 30.92 | −22.91 | 80.56 |

| Individual-level controls | |||||

| (4) | Age: 18–25 years | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| (5) | Age: 26–35 years | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| (6) | Age: 36–45 years | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| (7) | Age: 46–55 years | 0.25 | 0.43 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| (8) | Age: 56–64 years | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| (9) | Male | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| (10) | Immigrant | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| (11) | High_Income | 0.25 | 0.43 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| (12) | University_Degree | 0.27 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| (13) | Investor_Experience | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| (14) | Entrepreneurial_Experience | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| (15) | No_fear_of_failure | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| (16) | Entrepreneurial_Skills | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| (17) | Entrepreneurial_Exposure | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Region-level controls | |||||

| (18) | Unemploymentt-1 | 10.73 | 4.92 | 4.76 | 26.19 |

| (19) | Population_Densityt−1 | 1.83 | 1.94 | 0.24 | 7.85 |

| (20) | FirmStockt−1 | 7.31 | 0.71 | 6.07 | 9.14 |

| (21) | Industry_Unemploymentt−1 | 16.69 | 5.75 | 5.90 | 28.10 |

| (22) | Construction_Unemploymentt−1 | 12.07 | 2.32 | 8.00 | 17.00 |

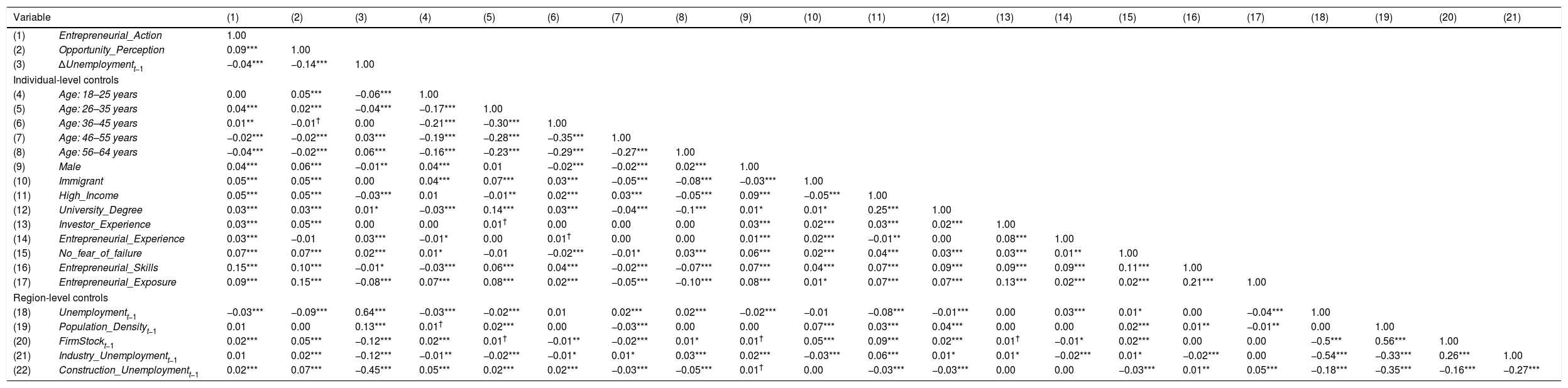

Correlation matrix.

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) | (15) | (16) | (17) | (18) | (19) | (20) | (21) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | Entrepreneurial_Action | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (2) | Opportunity_Perception | 0.09*** | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||||

| (3) | ΔUnemploymentt−1 | −0.04*** | −0.14*** | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Individual-level controls | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| (4) | Age: 18–25 years | 0.00 | 0.05*** | −0.06*** | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||

| (5) | Age: 26–35 years | 0.04*** | 0.02*** | −0.04*** | −0.17*** | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| (6) | Age: 36–45 years | 0.01** | −0.01† | 0.00 | −0.21*** | −0.30*** | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| (7) | Age: 46–55 years | −0.02*** | −0.02*** | 0.03*** | −0.19*** | −0.28*** | −0.35*** | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| (8) | Age: 56–64 years | −0.04*** | −0.02*** | 0.06*** | −0.16*** | −0.23*** | −0.29*** | −0.27*** | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| (9) | Male | 0.04*** | 0.06*** | −0.01** | 0.04*** | 0.01 | −0.02*** | −0.02*** | 0.02*** | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| (10) | Immigrant | 0.05*** | 0.05*** | 0.00 | 0.04*** | 0.07*** | 0.03*** | −0.05*** | −0.08*** | −0.03*** | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| (11) | High_Income | 0.05*** | 0.05*** | −0.03*** | 0.01 | −0.01** | 0.02*** | 0.03*** | −0.05*** | 0.09*** | −0.05*** | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| (12) | University_Degree | 0.03*** | 0.03*** | 0.01* | −0.03*** | 0.14*** | 0.03*** | −0.04*** | −0.1*** | 0.01* | 0.01* | 0.25*** | 1.00 | |||||||||

| (13) | Investor_Experience | 0.03*** | 0.05*** | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01† | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03*** | 0.02*** | 0.03*** | 0.02*** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| (14) | Entrepreneurial_Experience | 0.03*** | −0.01 | 0.03*** | −0.01* | 0.00 | 0.01† | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01*** | 0.02*** | −0.01** | 0.00 | 0.08*** | 1.00 | |||||||

| (15) | No_fear_of_failure | 0.07*** | 0.07*** | 0.02*** | 0.01* | −0.01 | −0.02*** | −0.01* | 0.03*** | 0.06*** | 0.02*** | 0.04*** | 0.03*** | 0.03*** | 0.01** | 1.00 | ||||||

| (16) | Entrepreneurial_Skills | 0.15*** | 0.10*** | −0.01* | −0.03*** | 0.06*** | 0.04*** | −0.02*** | −0.07*** | 0.07*** | 0.04*** | 0.07*** | 0.09*** | 0.09*** | 0.09*** | 0.11*** | 1.00 | |||||

| (17) | Entrepreneurial_Exposure | 0.09*** | 0.15*** | −0.08*** | 0.07*** | 0.08*** | 0.02*** | −0.05*** | −0.10*** | 0.08*** | 0.01* | 0.07*** | 0.07*** | 0.13*** | 0.02*** | 0.02*** | 0.21*** | 1.00 | ||||

| Region-level controls | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| (18) | Unemploymentt−1 | −0.03*** | −0.09*** | 0.64*** | −0.03*** | −0.02*** | 0.01 | 0.02*** | 0.02*** | −0.02*** | −0.01 | −0.08*** | −0.01*** | 0.00 | 0.03*** | 0.01* | 0.00 | −0.04*** | 1.00 | |||

| (19) | Population_Densityt−1 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.13*** | 0.01† | 0.02*** | 0.00 | −0.03*** | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07*** | 0.03*** | 0.04*** | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02*** | 0.01** | −0.01** | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||

| (20) | FirmStockt−1 | 0.02*** | 0.05*** | −0.12*** | 0.02*** | 0.01† | −0.01** | −0.02*** | 0.01* | 0.01† | 0.05*** | 0.09*** | 0.02*** | 0.01† | −0.01* | 0.02*** | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.5*** | 0.56*** | 1.00 | |

| (21) | Industry_Unemploymentt−1 | 0.01 | 0.02*** | −0.12*** | −0.01** | −0.02*** | −0.01* | 0.01* | 0.03*** | 0.02*** | −0.03*** | 0.06*** | 0.01* | 0.01* | −0.02*** | 0.01* | −0.02*** | 0.00 | −0.54*** | −0.33*** | 0.26*** | 1.00 |

| (22) | Construction_Unemploymentt−1 | 0.02*** | 0.07*** | −0.45*** | 0.05*** | 0.02*** | 0.02*** | −0.03*** | −0.05*** | 0.01† | 0.00 | −0.03*** | −0.03*** | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.03*** | 0.01** | 0.05*** | −0.18*** | −0.35*** | −0.16*** | −0.27*** |

Note: Level of statistical significance: ***p ≤ .001, **p ≤ .01, *p ≤ .05, †p ≤ .10.

On the other hand, the correlation matrix in Table 2 reveals that most explanatory variables are not highly correlated. However, a few coefficients were slightly above 0.50 (e.g., the coefficients between Unemployment_Rate and Industry_Employment or between Population_Density and Firm_Stock). To check whether these coefficients were suspicious of generating a problem of multicollinearity, variance inflation factor (VIF) scores were computed for all variables included in the study. None of the VIFs scores exceeded 5.0, providing evidence of no risk for multicollinearity among the explanatory variables (Bowerman and O’Connell, 1990).

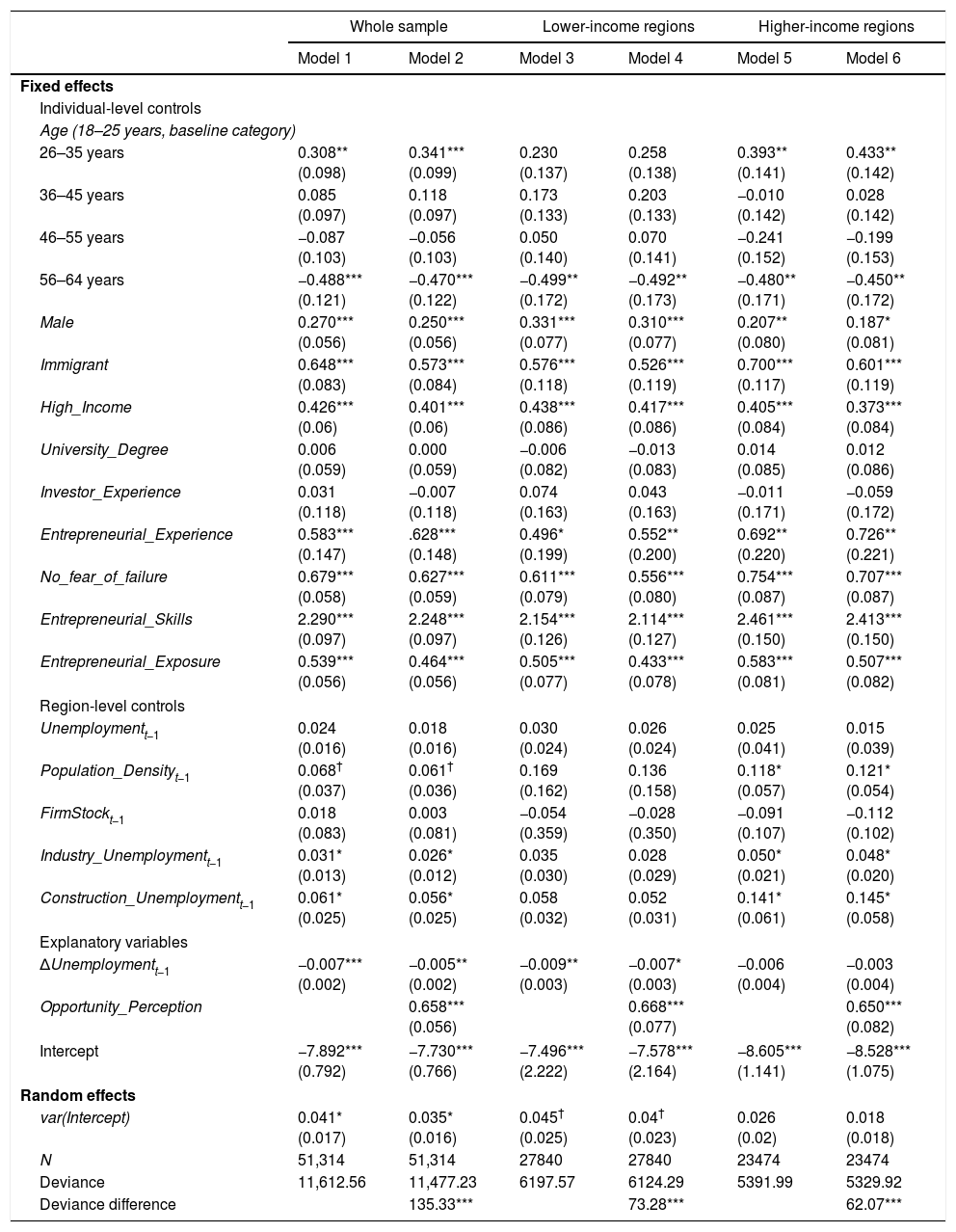

ResultsDirect effect of economic shake-out on entrepreneurial actionThe results shown in Table 3 correspond to the direct effect of the recession-driven economic shake out, through the change of unemployment rate, on the entrepreneurial action of individuals. Models 1 and 2 include the explanatory and mediator variables, and consistently show for the whole sample that the direct impact of the recession shock (i.e., the annual change in the regional unemployment rate during the period 2007–2010) on entrepreneurial action is negative and significant at the 0.001 level (Model 1). This finding supports hypothesis 1a and confirms previous findings on the pro-cyclical nature of entrepreneurship predicted by the emerging business cycle theory (Parker et al., 2012; Koellinger and Thurik, 2012; Santos et al., 2017). Respondents showed a lower propensity to engage in entrepreneurial activity in regions where the unemployment rate had increased more, confirming a pro-cyclical trend. Overall, we found evidence that a recessionary period exerts a negative direct effect on entrepreneurial action in general.

Multilevel logistic regression predicting entrepreneurial action, 2007–2010.

| Whole sample | Lower-income regions | Higher-income regions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Fixed effects | ||||||

| Individual-level controls | ||||||

| Age (18–25 years, baseline category) | ||||||

| 26–35 years | 0.308** (0.098) | 0.341*** (0.099) | 0.230 (0.137) | 0.258 (0.138) | 0.393** (0.141) | 0.433** (0.142) |

| 36–45 years | 0.085 (0.097) | 0.118 (0.097) | 0.173 (0.133) | 0.203 (0.133) | −0.010 (0.142) | 0.028 (0.142) |

| 46–55 years | −0.087 (0.103) | −0.056 (0.103) | 0.050 (0.140) | 0.070 (0.141) | −0.241 (0.152) | −0.199 (0.153) |

| 56–64 years | −0.488*** (0.121) | −0.470*** (0.122) | −0.499** (0.172) | −0.492** (0.173) | −0.480** (0.171) | −0.450** (0.172) |

| Male | 0.270*** (0.056) | 0.250*** (0.056) | 0.331*** (0.077) | 0.310*** (0.077) | 0.207** (0.080) | 0.187* (0.081) |

| Immigrant | 0.648*** (0.083) | 0.573*** (0.084) | 0.576*** (0.118) | 0.526*** (0.119) | 0.700*** (0.117) | 0.601*** (0.119) |

| High_Income | 0.426*** (0.06) | 0.401*** (0.06) | 0.438*** (0.086) | 0.417*** (0.086) | 0.405*** (0.084) | 0.373*** (0.084) |

| University_Degree | 0.006 (0.059) | 0.000 (0.059) | −0.006 (0.082) | −0.013 (0.083) | 0.014 (0.085) | 0.012 (0.086) |

| Investor_Experience | 0.031 (0.118) | −0.007 (0.118) | 0.074 (0.163) | 0.043 (0.163) | −0.011 (0.171) | −0.059 (0.172) |

| Entrepreneurial_Experience | 0.583*** (0.147) | .628*** (0.148) | 0.496* (0.199) | 0.552** (0.200) | 0.692** (0.220) | 0.726** (0.221) |

| No_fear_of_failure | 0.679*** (0.058) | 0.627*** (0.059) | 0.611*** (0.079) | 0.556*** (0.080) | 0.754*** (0.087) | 0.707*** (0.087) |

| Entrepreneurial_Skills | 2.290*** (0.097) | 2.248*** (0.097) | 2.154*** (0.126) | 2.114*** (0.127) | 2.461*** (0.150) | 2.413*** (0.150) |

| Entrepreneurial_Exposure | 0.539*** (0.056) | 0.464*** (0.056) | 0.505*** (0.077) | 0.433*** (0.078) | 0.583*** (0.081) | 0.507*** (0.082) |

| Region-level controls | ||||||

| Unemploymentt−1 | 0.024 (0.016) | 0.018 (0.016) | 0.030 (0.024) | 0.026 (0.024) | 0.025 (0.041) | 0.015 (0.039) |

| Population_Densityt−1 | 0.068† (0.037) | 0.061† (0.036) | 0.169 (0.162) | 0.136 (0.158) | 0.118* (0.057) | 0.121* (0.054) |

| FirmStockt−1 | 0.018 (0.083) | 0.003 (0.081) | −0.054 (0.359) | −0.028 (0.350) | −0.091 (0.107) | −0.112 (0.102) |

| Industry_Unemploymentt−1 | 0.031* (0.013) | 0.026* (0.012) | 0.035 (0.030) | 0.028 (0.029) | 0.050* (0.021) | 0.048* (0.020) |

| Construction_Unemploymentt−1 | 0.061* (0.025) | 0.056* (0.025) | 0.058 (0.032) | 0.052 (0.031) | 0.141* (0.061) | 0.145* (0.058) |

| Explanatory variables | ||||||

| ΔUnemploymentt−1 | −0.007*** (0.002) | −0.005** (0.002) | −0.009** (0.003) | −0.007* (0.003) | −0.006 (0.004) | −0.003 (0.004) |

| Opportunity_Perception | 0.658*** (0.056) | 0.668*** (0.077) | 0.650*** (0.082) | |||

| Intercept | −7.892*** (0.792) | −7.730*** (0.766) | −7.496*** (2.222) | −7.578*** (2.164) | −8.605*** (1.141) | −8.528*** (1.075) |

| Random effects | ||||||

| var(Intercept) | 0.041* (0.017) | 0.035* (0.016) | 0.045† (0.025) | 0.04† (0.023) | 0.026 (0.02) | 0.018 (0.018) |

| N | 51,314 | 51,314 | 27840 | 27840 | 23474 | 23474 |

| Deviance | 11,612.56 | 11,477.23 | 6197.57 | 6124.29 | 5391.99 | 5329.92 |

| Deviance difference | 135.33*** | 73.28*** | 62.07*** | |||

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses.

Level of statistical significance: ***p ≤ .001, **p ≤ .01, *p ≤ .05, †p ≤ .10.

To test hypothesis H1b, whether the shake-out effect of the economic crisis differed across local contexts, a median-split analysis was performed by separating the data into lower-income and higher-income sub-national regions. For that purpose, we used the indicator GDP per capita at the NUTS-2. Models 3 and 4 in Table 3 replicate the multilevel logistic regression analysis for the sample of individuals in lower-income regions, while models 5 and 6 do so in higher-income regions. The effect of the annual change in the unemployment rate of lower-income regions during the period of 2007–2010 was negative and significant at the 0.01 level (Models 3 and 4). The effect of the annual change in the unemployment rate of higher-income regions was negative but not significant (Models 5 and 6). Hence, we found partial support for hypothesis H1b, since the shake-out effect seems to be stronger for lower-income regions, as suggested in a previous work by Santos et al. (2017). The credit rationing argument provided by the authors may explain this result.

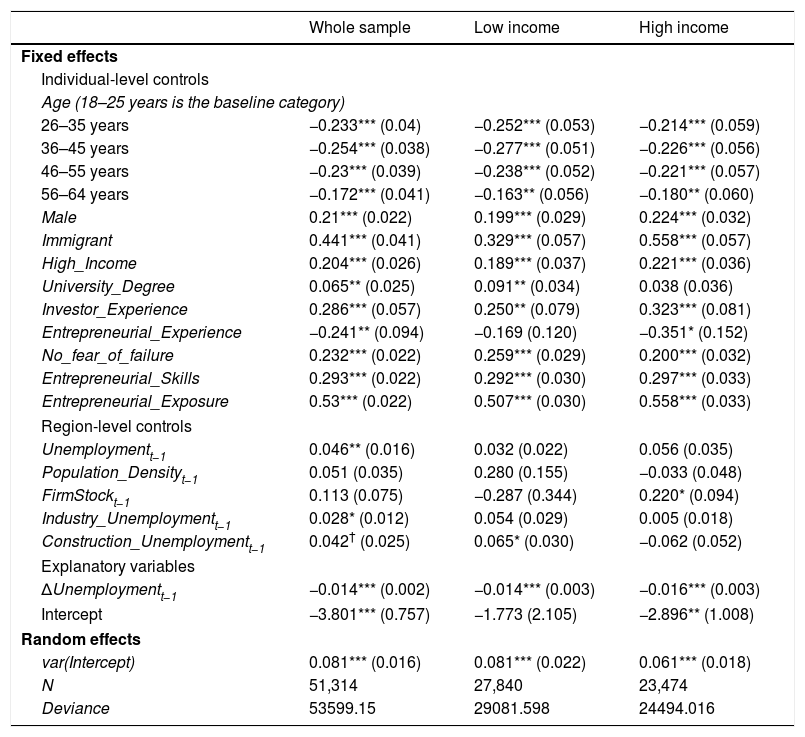

Indirect effect of shake out on entrepreneurial action mediated by opportunity perceptionTo test hypothesis 2a, we ran a multilevel logistic regression test by which we predict the effect of the change of the regional unemployment rate on the mediator variable: perception of business opportunities (i.e., Eq. (3) of our empirical model). Separate tests were conducted for the whole sample and the samples of individuals in lower-income and higher-income regions. The results are shown in Table 4. After considering the control variables, the annual change of the regional unemployment rate exerted a significantly negative effect on the perception of opportunities during the period of 2007–2010. In all the models tested, the coefficient of the unemployment rate change was significant at the 0.001 level. These results suggest that economic recession, measured by a rise in unemployment, negatively affected the opportunity perception of individuals to launch new businesses, specially in higher-income contexts (i.e., where the estimated coefficients are slightly higher with a negative sign).

Multilevel logistic regression predicting entrepreneurial opportunity perception, 2007–2010.

| Whole sample | Low income | High income | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | |||

| Individual-level controls | |||

| Age (18–25 years is the baseline category) | |||

| 26–35 years | −0.233*** (0.04) | −0.252*** (0.053) | −0.214*** (0.059) |

| 36–45 years | −0.254*** (0.038) | −0.277*** (0.051) | −0.226*** (0.056) |

| 46–55 years | −0.23*** (0.039) | −0.238*** (0.052) | −0.221*** (0.057) |

| 56–64 years | −0.172*** (0.041) | −0.163** (0.056) | −0.180** (0.060) |

| Male | 0.21*** (0.022) | 0.199*** (0.029) | 0.224*** (0.032) |

| Immigrant | 0.441*** (0.041) | 0.329*** (0.057) | 0.558*** (0.057) |

| High_Income | 0.204*** (0.026) | 0.189*** (0.037) | 0.221*** (0.036) |

| University_Degree | 0.065** (0.025) | 0.091** (0.034) | 0.038 (0.036) |

| Investor_Experience | 0.286*** (0.057) | 0.250** (0.079) | 0.323*** (0.081) |

| Entrepreneurial_Experience | −0.241** (0.094) | −0.169 (0.120) | −0.351* (0.152) |

| No_fear_of_failure | 0.232*** (0.022) | 0.259*** (0.029) | 0.200*** (0.032) |

| Entrepreneurial_Skills | 0.293*** (0.022) | 0.292*** (0.030) | 0.297*** (0.033) |

| Entrepreneurial_Exposure | 0.53*** (0.022) | 0.507*** (0.030) | 0.558*** (0.033) |

| Region-level controls | |||

| Unemploymentt−1 | 0.046** (0.016) | 0.032 (0.022) | 0.056 (0.035) |

| Population_Densityt−1 | 0.051 (0.035) | 0.280 (0.155) | −0.033 (0.048) |

| FirmStockt−1 | 0.113 (0.075) | −0.287 (0.344) | 0.220* (0.094) |

| Industry_Unemploymentt−1 | 0.028* (0.012) | 0.054 (0.029) | 0.005 (0.018) |

| Construction_Unemploymentt−1 | 0.042† (0.025) | 0.065* (0.030) | −0.062 (0.052) |

| Explanatory variables | |||

| ΔUnemploymentt−1 | −0.014*** (0.002) | −0.014*** (0.003) | −0.016*** (0.003) |

| Intercept | −3.801*** (0.757) | −1.773 (2.105) | −2.896** (1.008) |

| Random effects | |||

| var(Intercept) | 0.081*** (0.016) | 0.081*** (0.022) | 0.061*** (0.018) |

| N | 51,314 | 27,840 | 23,474 |

| Deviance | 53599.15 | 29081.598 | 24494.016 |

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses.

Level of statistical significance: ***p ≤ .001, **p ≤ .01, *p ≤ .05, †p ≤ .10.

The indirect effect of unemployment rate changes on individual entrepreneurial action was measured by testing the mediation role of individual perceptions of business opportunities. It is worth mentioning that the mediator variable, perception of business opportunities, had a positive and significant influence on the variable entrepreneurial action during the period affected by the economic recession (see Models 2, 4 and 6 in Table 3). These results support hypothesis 2b. Indeed, according to our results the core notion of the theory of planned behaviour holds. Negative entrepreneurial perceptions and intentions result in reduced entrepreneurial action (i.e., new firm creation), as suggested by Nabi and Liñán (2013).

A preliminary test of mediation was applied for hypothesis 2c, following the standard procedure proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986). According to this procedure, mediation exists if three conditions are met. First, the explanatory variable is a significant predictor of both the dependent variable and the mediator variable. Second, the mediator variable is a significant predictor of the dependent variable. Third, the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable decreases when the mediator is added to the regression model. If the effect of the explanatory variable is no longer significant when the mediator is added, then the effect is fully mediated; if the effect of the explanatory variables is reduced but significant, then the effect is partially mediated.

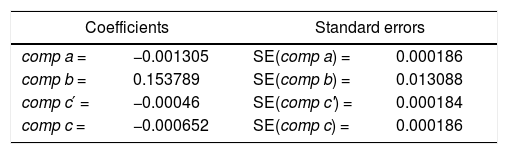

The results for the whole sample in Tables 3 and 4 show that the three abovementioned conditions were met. Thus, the negative effect of unemployment rate changes on individual entrepreneurial action was mediated by the individual perception of business opportunities. And this mediation was partial since the shake-out effect decreased but remained significant after adding the mediator. We conducted an additional robustness check by estimating the mediation effect and a test of significance (Sobel, 1982). Because coefficient estimates from logistic regressions cannot be directly compared across models, coefficients involved in the mediation shown in Fig. 2 were standardized before estimating the mediation effect (MacKinnon, 2008).3Table 5 shows the standardized coefficients comp a, comp b, comp c′ and comp c for the whole sample. The mediation or indirect effect represented 30.30% of the total effect of the unemployment rate change on an individual’s propensity to become an entrepreneur.4 Using the standardized coefficients, a Sobel (1982) test was run to assess the significance of the mediation effect given by comp a * comp b. After running the Sobel test (−6.015, p < .0001), we can conclude that the negative indirect effect of the change in the regional unemployment rate on the individual entrepreneurial action was significantly mediated by the individual perception of business opportunities.

Therefore, the results suggest that opportunity perceptions mediated the relationship between unemployment rate changes and entrepreneurial activity (i.e., hypothesis 2c is accepted). In other words, there exists a negative indirect effect between the change in the regional unemployment rate and the individual entrepreneurial action that is partially mediated by individual perception of business opportunities, and this mediation represents approximately 30.30% of the total effect. This finding supports our idea that the entrepreneurial process follows a logical sequence advocated by the Azjenian theory of planned behaviour (Krueger, 1993; Mitchell et al, 2002). Firm creation occurs after business opportunity perception. Our results show that the shake-out hits first the exploratory phase of opportunity perception, which in turn, hurts later the entrepreneurial action stage (i.e., new firm creation). Like in Stuetzer et al. (2014), we believe that the entrepreneurial action perspective may fall short in explaining how the economic recession affects entrepreneurship. A more accurate view of the phenomenon suggests that an entrepreneurial process angle provides a broader understanding on why and how entrepreneurship is pro-cyclical and it declines during shrinking economic periods. Our findings complement the results obtained by other business cycle theorists (Parker, 2012; Fairlie, 2013) and are in line with recent results exhibited in the context of Europe (Santos et al. 2017; Vegetti and Adăscăliţei, 2017).

Most control variables behave as expected. It should be noted that University_Degree and Investor_ Experience show a positive and significant association with opportunity perception but are not significant and with different signs for entrepreneurial action in low and high-income regions. Entrepreneurial_Experience shows a positive and significant association with entrepreneurial action, but a negative one with opportunity perception.

ConclusionWhile there are numerous stylized facts on firm entry, exit, survival and growth (Geroski, 1995), the literature has not resolved yet the long debate on the relationship between business cycles and entrepreneurship. Most studies support the opinion that such a relationship is complex, and the subject still warrants further research (Acs and Storey, 2004; Audretsch and Peña-Legazkue, 2011; Fritsch, 2008).

Our findings suggest that economic context matters for the process, rather than the action, of entrepreneurship. Specifically, a recession-driven shakeout generates a decline in entrepreneurship, and our mediation tests reflect that lower entrepreneurial activity is to some extent explained by a reduced opportunity perception of individuals during recessionary periods. Rather than a full direct effect of the economic shakeout on entrepreneurial activity, consistent with cognitive and planned behaviour theories, we empirically demonstrated that this relationship is partially mediated through a lower and more pessimistic opportunity perception, which leads to a drop in entrepreneurial action.

The paper is not without limitations. Only one proxy has been used to describe the recession shakeout effect (e.g., changes in unemployment rate of regions as in the study by Fritsch et al., 2015), and the study is limited to the case of Spain during a precise economic recessionary period (2007–2010). Although the results can be seen as solid and valid enough as several additional tests for robustness were conducted (e.g., findings were similar when other proxies of the current crisis were considered, such as changes in GDP per capita), we suggest that further studies should be undertaken in other geographical contexts to authenticate our entrepreneurial process view.

The results provide interesting implications for policymakers. First, an economic cycle correlates positively with the entrepreneurial process. During an economic downturn, the propensity to start new firms declines. Government authorities should design policies to counterbalance this trend, since entrepreneurship creates new and, at times, durable jobs. A crucial implication consists of fostering an entrepreneurial culture in the society despite socio-economic values and conditions that dissuade entrepreneurship. Moreover, supporting efforts should be stronger when the economic context is adverse (Bishop and Shilcof, 2017; Williams and Vorley, 2014). Second, we believe that this relationship is essentially due to reduced expectations and opportunity perception by individuals during recessionary cycles. Policymakers should think about actions to increase the awareness and interest of individuals seeking new opportunities during economic collapse. Government actions should especially not only target but also stimulate the most motivated and capable individuals (i.e., picking- winners type of policy) to create and run new businesses, since this segment is likely to contribute the most to productive entrepreneurship and to the recovery of distressed areas. As stressed by Williams and Vorley (2015), “…in responding to crises, the ability of governments to affect positive institutional change is not straightforward and often severely restricted”. Therefore, policymakers should favor stable institutional settings oriented to sharpening the creativity and to strengthening the identification of innovative business ideas derived from an economic crisis rather than fostering the entrepreneurial action per se as an occupational solution for subsistence. Entrepreneurship education is a key vehicle to learn how to recognize business opportunities. Besides, teaching technical skills for entrepreneurship can mitigate the risk of failure (Santos et al., 2017; Simón-Moya et al., 2014).

In addition, policymakers should be aware of the heterogeneous entrepreneurial activity displayed across sub-national contexts (Bishop and Shilcof, 2017; González-Pernía et al., 2012). Our findings show that the entrepreneurial process evolves differently in regions with higher and lower levels of income per capita. Erga omne policies for all sub-national regions (i.e., the Law of Entrepreneurship passed by the Spanish parliament in 2013) would not suffice, as the ‘‘counterproductive destruction’’ and ‘‘productive cleansing’’ effect of an economic recession on entrepreneurship is far from being identical across different locations (Acs et al., 2015; Fairlie, 2013). Caution is recommended in the implementation of support policies, specially in economically distressed areas. Necessity-driven entrepreneurs are relatively more abundant in lower income regions, and precisely, these are the locations with larger needs for entrepreneurship education and training. An important challenge for policy makers consists on transforming most necessity-driven entrepreneurs in productive entreprenurs in a Baumolian sense. This would allow to improve not the quantity, but the quality of entrepreneurship in such areas. Therefore, rather than generic education and traning programmes, policy makers should design tailor-made educational programs aimed at attending people who find themselves at risk of social exclusion.

Several avenues for future research are suggested. It would be interesting to study the influence of other mediating factors between the economic context (i.e., business cycles) and entrepreneurial action to better understand the process of firm creation. In this paper, opportunity perception was analyzed as a coherent mediator in the entrepreneurial process, but the effect of other mediators subjected to policy intervention remains to be explored (i.e., fear of business failure, self-confidence about entrepreneurship skills, etc.). Comparing the results with other findings from distinct economic contexts and business cycles may confirm (or challenge) the consistency of this phenomenon. Our study could be enhanced if the study of the shakeout effect focused not only on the quantity of start-up firms but also on the quality of the firms created during economic recession periods (e.g., rates of high-growth or gazelle firms, global-born firms, innovation-driven firms, etc.) and the motivation for firm creation: opportunity versus necessity-driven entrepreneurship (i.e., as in Fairlie and Fossen, 2018; Fuentelsaz et al., 2015). These are intriguing issues that we leave for further research.

FundingThe authors are grateful for the financial support of IT-1050, granted by the Department of Education of the Basque Government.

Conflict of interestNone.

The authors are grateful to participants at the RENT XXIX Conference for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper. The authors also thank two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions to improve the manuscript. Any errors, interpretations and omissions are the authors’ responsibility. This research was supported by the Department of Education of the Basque Government (financial support IT-1050).

For instance, according to the Spanish National Institute of Statistics, the unemployment rate in Spain rose from 8.2% in 2007 to 19.9% in 2010; however, at the end of the period, the difference between the lowest and highest unemployment rates at the region-level was approximately 18 percentage points. In terms of GDP growth, the regional disparities were similar.

The intra-class correlation indicates the proportion of the variance due to the aggregate level-2 unit. According to Guo and Zhao (2000), the intra-class correlation for binary data models can be estimated as follows: ρ=σu2/σu2+Π2/3.

This is done by multiplying each coefficient by the standard deviation of its corresponding predictor variable and then dividing the product by the standard deviation of the outcome variable. For more details, see Mackinnon and Dwyer (1993) and MacKinnon (2008, p. 306-307).

The percentage explained by the indirect effect is estimated as follows: a * b/(a * b + c′) = 0.0002/(0.0002 + 0.00046) = 0.3030.