Previous research has analyzed the imprinting effect associated with the firm's international expansion without considering the full range of differences between home and host countries. These differences are important because, depending on the development gap, and the direction of the difference, learning opportunities and the possibility of upgrading firm's capabilities will be vastly different. For this reason, we analyze the specific influence of the exposure to a specific group of international markets, those that are more developed than the country of origin of the focal firm. Obviously, this exposure benefits especially firms from emerging and middle-income countries, which we refer to as “new multinationals.” We analyze the different factors that influence the nature and intensity of the imprinting effect associated to the exposure to developed international markets by new multinationals.

Since the late 1980s the phenomenon of accelerated internationalization has become more visible, both in advanced and emerging economies (Guillén and García-Canal, 2009). Two groups of companies have called the attention of business media and academics: born global firms (Oviatt and McDougall, 1994; Cavusgil and Knight, 2015) and emerging market multinationals (Mathews, 2006; Madhok and Keyhani, 2012; Narula, 2012). The accelerated growth shown by the most conspicuous members of these groups has challenged the traditional assumptions of established theories on the internationalization process. Instead of following a gradual exposure to foreign markets, these firms expand quickly to increase their international reach, moving beyond what would be advisable according to their experience and knowledge (Buckley et al., 2018; Verbeke and Kano, 2015). This overexposure to international markets can be modeled as a trade-off between the increased risk in foreign operations and the knowledge and experience spillovers that can be obtained (Guillén and García-Canal, 2013). Regarding these spillovers, Sapienza et al. (2006) have highlighted the importance of an early exposure to international markets to activate and enhance dynamic capabilities that favor internationalization through a process of imprinting. Their work was the first to consider the possibility of international imprinting and its positive effect on firm competitiveness. Every new country entered requires adjustments in the firms’ capabilities. For this reason, they argued that companies familiarized with expanding to new countries since their early days have a deeply imprinted dynamic capability for making these adjustments (Sapienza et al., 2006). Imprinting theory focuses on the persisting impact that the environment exerts in firms’ routines during sensitive periods, like the early stages of their existence (Stinchcombe, 1965; Marquis and Tilcsik, 2013). For this reason, the intensity and the persistence of the foreign environment's influence on a firm expanding abroad can be expected to be different according to the timing of the expansion. Thus, this line of research acknowledges the fact that foreign environments, and not only the home country environment, can also leave a positive lasting mark in firm routines. However, previous research only considers the possibility of international imprinting associated to this dynamic capability, without accounting for the characteristics of either the host or the home country of the firm expanding abroad. Consequently, two important questions remain unanswered. First, are all external environments equally able to exert a positive external influence in the internationalizing firm? Second, are all firms (regardless of their origins and background) equally permeable to external international influences?

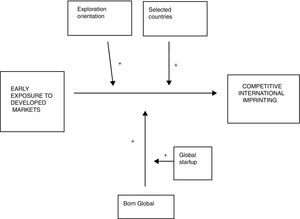

To answer these questions, we develop a theoretical framework to explain the magnitude of the imprinting effect associated with the exposure of international developed markets. In this paper we argue that it is in the most developed markets where more opportunities exist for positive external influences, so the country of destination would condition the magnitude of the imprinting effect associated to international expansion. In addition, the country of origin would also have an influence, because it is the gap between the home and the host country that determines the possible spillovers that may arise from international expansion. We build on previous theoretical developments in the imprinting field, complemented with the knowledge-based view of the firm (Kogut and Zander, 1992, 1993; Grant, 1996) to explain the benefits of being exposed to the most developed markets.

We add to the literature on international imprinting by highlighting the fact that to properly analyze its magnitude we need to focus on the features of both the home and the host country environments. Our main point is that the effects of early exposure to international markets will depend on the development gap between home and host countries. We believe that it is important to analyze the main features of the markets the firm gets exposed to. Depending on the features of the country of destination, as compared to those of the home country, the firm is going to face different challenges and have access to different resources (Kim et al., 2015). As a consequence, the adjustments that can be expected in the structure and processes are different.

In the sections that follow, after providing some background on the causes and consequences of imprinting, we analyze the different factors that influence the intensity and strength of the imprinting effect associated to the exposure to more developed markets than the one of the focal firm. As previously mentioned, we argue that the relationship between home and host country matters, given that relative differences in economic development are the main drivers of this international competitive imprinting. We discuss the imprinting effect of the country of origin by relating our work to existing theories on the MNE and, more specifically, to the approaches explaining the international expansion of firms from middle income, newly industrialized and emerging countries. We refer to these firms as “new multinationals” (Guillén and García-Canal, 2009). The main reason for grouping together this wide set of countries is that, despite their differences, these companies have the opportunity to overcome the constraints of their home countries in terms of technology development and brand reputation by being exposed to more developed markets. We also analyze the boundary conditions of international competitive imprinting. To fully identify the boundary conditions of this exposure, we examine its interaction with the main elements of a firm's international strategy, namely, the when (stage of the life cycle), where (location), and the why (motives for international expansion). We also discuss at the end of the paper how this exposure to developed markets can be active (by serving other markets) or passive (by engaging with other firms from other countries that act as suppliers of raw materials, parts, or technologies).

Domestic and international organizational imprintingThe relationship between organizations and their environments has been extensively studied from different perspectives. Whereas some approaches tend to focus on how organizations shape their environment, others highlight the influence of the latter on the firm's structure and strategy (Astley and Van de Ven, 1983; Child, 1997; Lewin and Volberda, 1999). It is unquestionable that the interaction of the organization with its environment leaves a mark in its structure and processes, but there is an established tradition in organization theory showing that this influence is more important at the early stages of the life of an organization. The classic work of Stinchcombe (1965) was the first to identify this phenomenon, which is labeled as imprinting. We follow the definition of Hannan et al. (1996: 507), for whom imprinting is “a process by which events occurring at certain key developmental stages have persisting, if not lifelong consequence”. In this way, during the early stages of the life cycle of an organization, firms are more sensitive to external influences for a number of reasons, being the absence of previously established structure and routines one of the most important ones. On the contrary, at later stages of a firm's life cycle, inertia and resistance to change, coupled with institutionalization and positive feedback, reinforce the organizational practices established at the early stages (Simsek et al., 2015).

According to Marquis and Tilcsik (2013, p. 199), imprinting is the outcome of three sequential events: (1) a sensitive exposure to the environment in a specific moment of time; (2) adjustment of the organizational structure due to the influence of the environment; and (3) persistence of the imprinted structure and routines over time, even after new environmental changes take place. Thus, it is during sensitive periods, characterized by uncertainty and instability when the organizational structure, processes and capabilities become more permeable to the influence of the environment. As a consequence, the capabilities and routines established during periods of sensitivity shape future behavior inside the firm and, thus, what the firm is capable of doing and accomplishing in the future (Tilcsik, 2014). These routines persist after changes in the environment (Kogut and Zander, 2000; Tilcsik, 2010) and are hard to replicate and transfer to external organizations (Uzunca, 2016).

Imprinting offers an explanation to organization evolution that is different to other concepts that are usually used for the same purposes, such as path dependence. Whereas path dependence focuses on a chain of related events to explain how the past shapes the future, imprinting theory focuses on the persistence of the impact of the environment during specific sensitive periods, regardless of subsequent events (Marquis and Tilcsik, 2013).

Most research on organizational imprinting has focused on the early years of existence of the company by highlighting the influence of the situation at that time (e.g. Kimberly, 1979) and/or the role of the founder (Schein, 1983). However, sensitive periods comprise not only the initial years of the firm's life cycle, but also other special periods during which for specific reasons the company is more open to influences from the environment. These periods of highly sensitive influence are more likely to occur during times of transition, when the organization enters into a new field lacking established routines and procedures to operate (Marquis and Tilcsik, 2013). One example is international expansion (Autio et al., 2000; Sapienza et al., 2006). Foreign countries are a source of learning and new knowledge that can leave a lasting dent on the firm's structure and processes.

And yet, previous research on the role of imprinting in international expansion has focused mainly on the influence of the home-country environment on international strategic choices (for a review, see Zhou and Guillén, 2015). One of the few exceptions is the work of Sapienza et al. (2006), who argue that the earlier an organization expands abroad, the stronger the degree of imprinting of its dynamic capability for exploiting opportunities in foreign markets. In their work they turn their focus to the external influences received from the host country. In this way, we can define international imprinting as the process through which the market forces and the institutional environment of the initial countries where a firm starts its international expansion shape its routines and capabilities to deal with international expansion and international operations.

International imprinting and the development gap between host and home countriesWhen a firm expands abroad for the first time, it lacks experience in dealing with international markets, and specifically in adapting its business model to exploit foreign business opportunities. The need to succeed in a market different than the home one forces the firm to reconsider its procedures and routines. This is important because in each new country the firm faces local competition whose capabilities have been shaped by the local environment and institutions (Porter, 1990) and, for this same reason, fully adapted to compete in this environment. That is why the process of international expansion is usually seen as a learning process through which firms adapt their strategies according to what they learn in foreign markets (Johanson and Vahlne, 1977). However, this process of local adaptation usually becomes routinized (Madhok, 1997), leaving less leeway to the influence of the environment. That is why the firm's earlier experiences in foreign markets condition the adoption of the main routines to adapt and exploit foreign business opportunities.

International expansion entails a tradeoff between risk and return. Expanding abroad requires investing resources and exposing the firm to new markets in a process surrounded by uncertainty. Thus, this expansion can generate losses for the firm, reducing its chances of survival. However, it also can improve its growth prospects by opening new markets and accumulating resources and experience in the form of new capabilities that can be of help when expanding into other countries (Sapienza et al., 2006). Exposing a firm to more developed markets at the early stages of its international expansion exacerbates this tradeoff. Not all international markets are equally challenging, nor do they have the same potential to provide new sources of knowledge (Guillén and García-Canal, 2009), as countries have different strategic factor markets (Kim et al., 2015). Developed countries are more demanding in terms of product design, technology and service, because they usually have more sophisticated customers and stronger competitors that take advantage of the rich set of resources and capabilities available in the local strategic factor markets (Kim et al., 2015). As a consequence, it is difficult to make a profit in them. On the contrary, emerging countries have, other things being equal, a less challenging environment in terms of customers and competition. These counties may have other difficulties of their own, because they usually do not have strong institutions (North, 1990) and firms not used to compete in these environments may find difficult to operate in them (Cuervo-Cazurra and Genc, 2008). At any rate, the firm is not exposed to cutting edge technologies or demands, due to the relative poor set of resources and capabilities available in the local strategic factor markets (Kim et al., 2015). This is the reason why the previously mentioned tradeoff between risk and return is different for developed and developing countries. In developed markets it is more difficult to beat local competition in terms of product design or brands, so firms face a higher risk in terms of succeeding in the market, although the feedback and learning that they receive from this competition can increase the international competitiveness of their products. In fact, in some cases the spillovers coming from the feedback can counteract the negative results in the foreign country, because the firm can overcome its technological deficit. This fact explains why some leading emerging market multinationals have invested and expanded early into developed countries just for the sake of catching up with established multinationals (Guillén and García-Canal, 2013).

This evidence regarding emerging market multinationals has led some scholars to argue that these firms can benefit from “springboard” strategies aimed at gaining access to strategic assets and know-how from developed markets with the aim of filling their competitive gap with established multinationals (Luo and Tung, 2007). It is clear that the country of origin of the firm conditions the magnitude of the potential international imprinting effect, as what matters is not the absolute degree of development of the host country, but the development gap between the home and the host countries. In this way we can classify firms/countries into three big groups considering their international competitive imprinting possibilities: firms from the most developed countries, which have few competitive imprinting options, as they cannot expand to countries being more developed than theirs; firms from middle income and newly industrialized countries, which can choose either more developed or less developed countries; and, finally, firms from emerging markets, which have a number of imprinting opportunities, as most of the countries where they can enter are more developed than theirs.

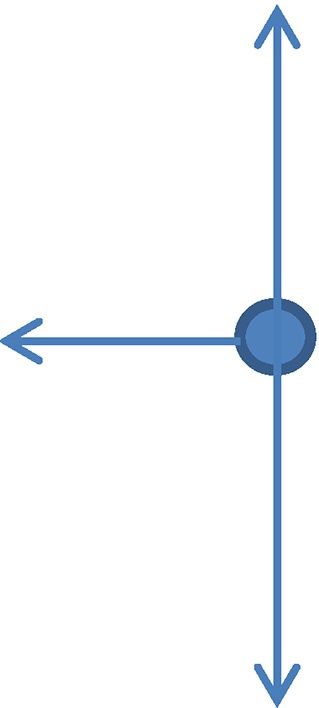

Interestingly, most of the theoretical approaches in the international business field have been developed keeping in mind either the typical international expansion of established multinationals or the latecomers. Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the international expansion of established, middle income and emerging market multinationals. Dominant, mainstream, approaches to the MNE, like internalization/transaction cost Theory (Buckley and Casson, 1976; Hennart, 1982) or the product life cycle (Vernon, 1979) have been inspired by the expansion of developed country multinationals, assuming that they expand abroad in a number of countries to exploit distinctive competitive advantages, usually technologies, brands and superior knowledge. Firms from middle income and newly industrialized countries, such as South Korea or Spain have also received attention. These approaches highlight additional competitive advantages, such as project execution capabilities (Amsden and Hikino, 1994) or the ability to manage external growth through alliances and acquisitions. Guillén and García-Canal (2010) also highlight that these firms follow a dual expansion path entering simultaneously into more and less developed countries following strategies of exploration and exploitation at the same time. Finally, research on emerging market multinationals have evolved from the traditional approaches of the 1970s and 80s, that focused on the expansion to other developing countries, to the recent approaches of Springboard (Luo and Tung, 2007) or the Linkage, Leverage and Learning framework (Mathews, 2006) that highlight how firms catch up with established competitors by learning or gaining access to their skills. Other approaches also highlight that EMMs have an advantage when entering into countries with weak institutional environments1 (Cuervo-Cazurra and Genc, 2008). Even though some of these theories acknowledge the importance of the exposure to developed countries and/or firms from more developed countries, none of them have paid attention to the role of imprinting in this process of exploration and capability upgrading. Understanding how this competitive international imprinting process works is critical to properly analyze the causes and consequences of the catching up processes undertaken by firms from emerging, middle income and newly industrialized countries. In this way, our framework does not intend to substitute current theories of internationalization but rather complement them by providing a comprehensive view of the process through which some firms may benefit from international imprinting.

Home-country degree of development and theoretical approaches to the MNE.

| Traditional MNEs | Middle-income & newly-industrialized country MNEs | Emerging-market MNEs | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intangible assets | State-of-the-art technologies and renowned brands | Technologies and brands Project-execution capabilities External-growth capabilities | Low-cost capabilities Execution skills Ability to deal with weak institutional environments |

| Speed of internationalization | Gradual | Accelerated | Accelerated |

| Default entry mode | Wholly-owned subsidiaries | Alliances, mergers, and acquisitions | Alliances, mergers, and acquisitions |

| Direction of FDI flows (Upwards: more developed countries/downwards: less developed countries) | |||

| Representative countries of origin | USA, France, UK, Holland, Germany, Japan | Spain, South Korea, Mexico, Brazil, India/China (2010s) | India or China (1980s–2000s) |

| Representative theories | Internalization/transaction costs (Buckley and Casson; Hennart) Product Life Cycle (Vernon) | Project-execution capabilities (Amsden & Hikino), Dual expansion path (Guillén and García-Canal) | Springboard (Luo and Tung) LLL (Mathews) Comparative institutions (Cuervo-Cazurra and Genc) |

| International competitive imprinting opportunities | Low | Med/high | High |

It is widely acknowledged that firms learn and adapt their routines and capabilities according to their interaction with their environment. However, according to the concept of international imprinting previously introduced, it is at the beginning of the process of international expansion where this influence becomes more pervasive. Firms learn to identify and exploit international business opportunities, but the routines and feedback that emerge from their initial international experiences are conditioned by the local environment and institutions of the countries entered. These early experiences shape what they can do in the future. In effect, these routines and dynamic capabilities adjusted after the entry into a specific set of countries prepare the firm better to expand into similar countries instead of other countries with different degree of development. In fact, some evidence exists showing that firms tend to expand to countries similar to those where they have been operating before, either through exporting (Morales et al., 2014) or through foreign direct investment (Zhou and Guillén, 2015). In this context, and thinking in the case of a New Multinational, that can choose to enter into countries with lower or higher level of development, the main advantage of the early exposure to developed markets is that firms can improve their technological and marketing capabilities. Even though the entry into a resource-richer country always allows the firm to gain access to new capabilities and knowledge, the higher receptiveness to external influences that characterize the early stages of the international expansion facilitates capabilities and routine upgrading. In addition, these improved capabilities can be capitalized later in all markets.

On the contrary, new multinationals only active in developing or less developed countries are prepared to enter in these countries (Cuervo-Cazurra and Genc, 2008) but ill prepared to enter into more developed countries. Organizational inertia and institutionalization put new multinationals only used to compete in developing countries at a disadvantage when it comes to entering more developed countries. For instance, Brazilian Natura Cosméticos expanded successfully its business model of selling door-to-door ecological cosmetics throughout all Latin America in an internationalization process that started in 1982. However, when they approached the French market in 2005 they found difficult to replicate its business model given that direct sales account for only a marginal fraction of the market and they lacked experience in managing alternative distribution channels (Guillén and García-Canal, 2013). The absence of exposure to developed countries can limit the possibilities of replicating the company's business model in more sophisticated countries. Hence, we expect that:Proposition 1 Early exposure to more developed markets at the beginning of the process of international expansion enables new multinationals to accumulate new capabilities that increase their international competitiveness.

Obviously, this improvement in international competitiveness may come at the cost of poor performance in the host country. Thus, the net effect of the exposure of new multinationals to developed markets will be dependent on the intensity of this exposure in terms of the motives of the entry, the number of countries, and the timing of the entry. In the following sections we analyze how these elements of a firm's international strategy delineate the boundary conditions for an effective international imprinting.

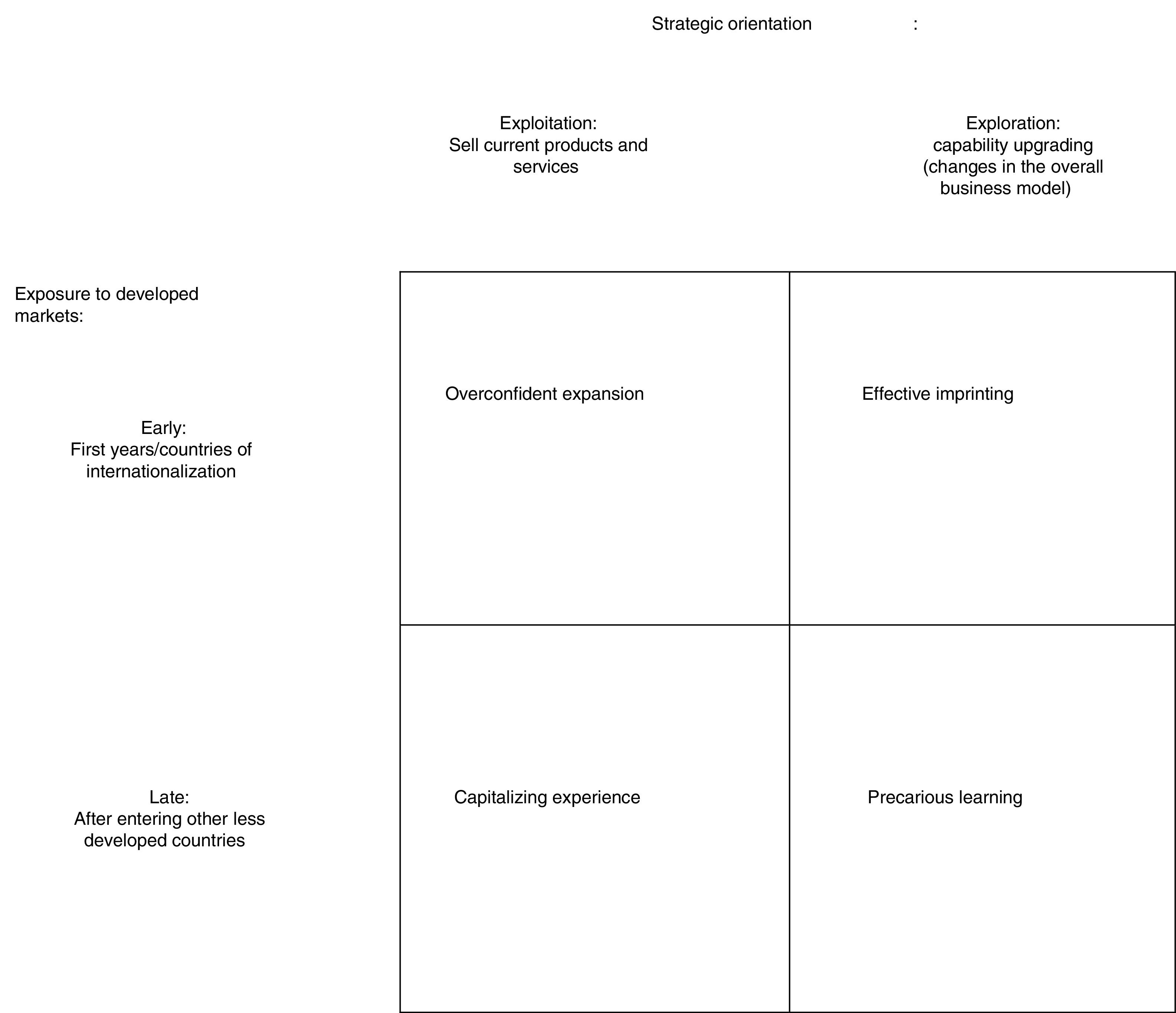

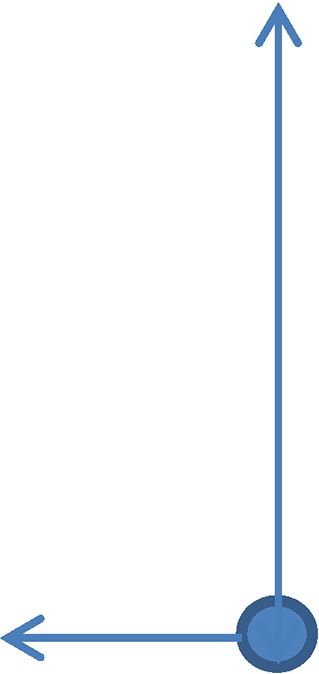

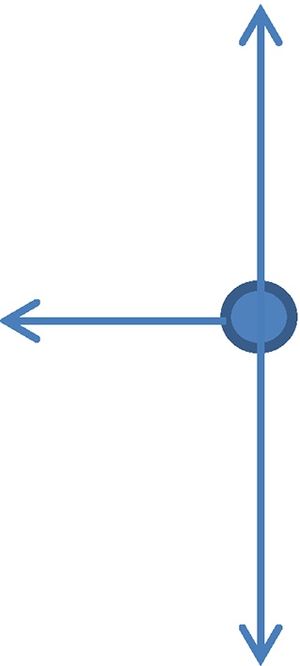

International imprinting and motives for international expansionWe argue that not all firms are equally receptive to external influences when they expand abroad. Whereas some firms enter into international markets to exploit their current competitive advantages, others try to explore and develop new sources of competitiveness (March, 1991; Madhok, 1997). In addition, as previously mentioned, the exposure to developed markets can take place at the beginning of the firm's international expansion or later in the process. According to this, we can identify four different scenarios for imprinting according to the timing of the entry into developed markets and the strategic orientation of the firm (see Fig. 1). New multinationals exposed to developed countries at the earlier stages of their internationalization process are more likely to benefit from this exposure than firms entering in them in later stages. However, New multinationals with an exploration orientation are the ones which can benefit the most from imprinting, because they are more willing to expand their knowledge base and more willing to adjust their structure and processes than those with just a mere exploitation orientation. One illustration is the case of Haier, the Chinese appliance manufacturer. Its first foreign destination was the U.S. The company wanted to try itself in a demanding market and was eager to make the required adjustments to succeed there. The logic of this exposure, as stated by its CEO, was that, “if we can effectively compete in the mature markets with such brand names as GE, Matsushita and Philips, we can surely take the markets in the developing countries without much effort” (Yi and Ye, 2003). This expansion of their knowledge base also serves as a platform to profit from future learning opportunities, because of their expanded absorptive capacity (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990; Madhok, 1997). On the contrary, firms exposed early to developed markets, but with an exploitation orientation, may be penalized for their overconfident expansion because their products and/or services may not be good enough to compete with local firms. In addition, their lower openness to external influences reduces their learning opportunities and, consequently, the intensity of the potential competitive imprinting.

New multinationals that enter developed countries in the later stages of their international expansion process are less likely to benefit from imprinting because of the inertia and resistance to change associated to their established routines. However, the expertise accumulated in their initial expansion could be capitalized by following an exploitation approach. This would be the case of firms following a gradual/cautious approach to international expansion that wait to enter into the most developed markets until they have succeeded in less developed ones. As they have their business model already refined, as well as established routines, they may be better off by exploiting their products and services in some market niches that value them, rather than embarking in an exploratory strategy aimed at changing the already imprinted dynamic capabilities and routines developed at the early stages of their international expansion into emerging markets. These dynamic capabilities and routines can be already institutionalized and, for this reason, difficult to change. Thus, we argue that:Proposition 2 New multinationals exposed to developed markets at the early stages of their international expansion and with an exploration orientation benefit more from this exposure than other types of firms.

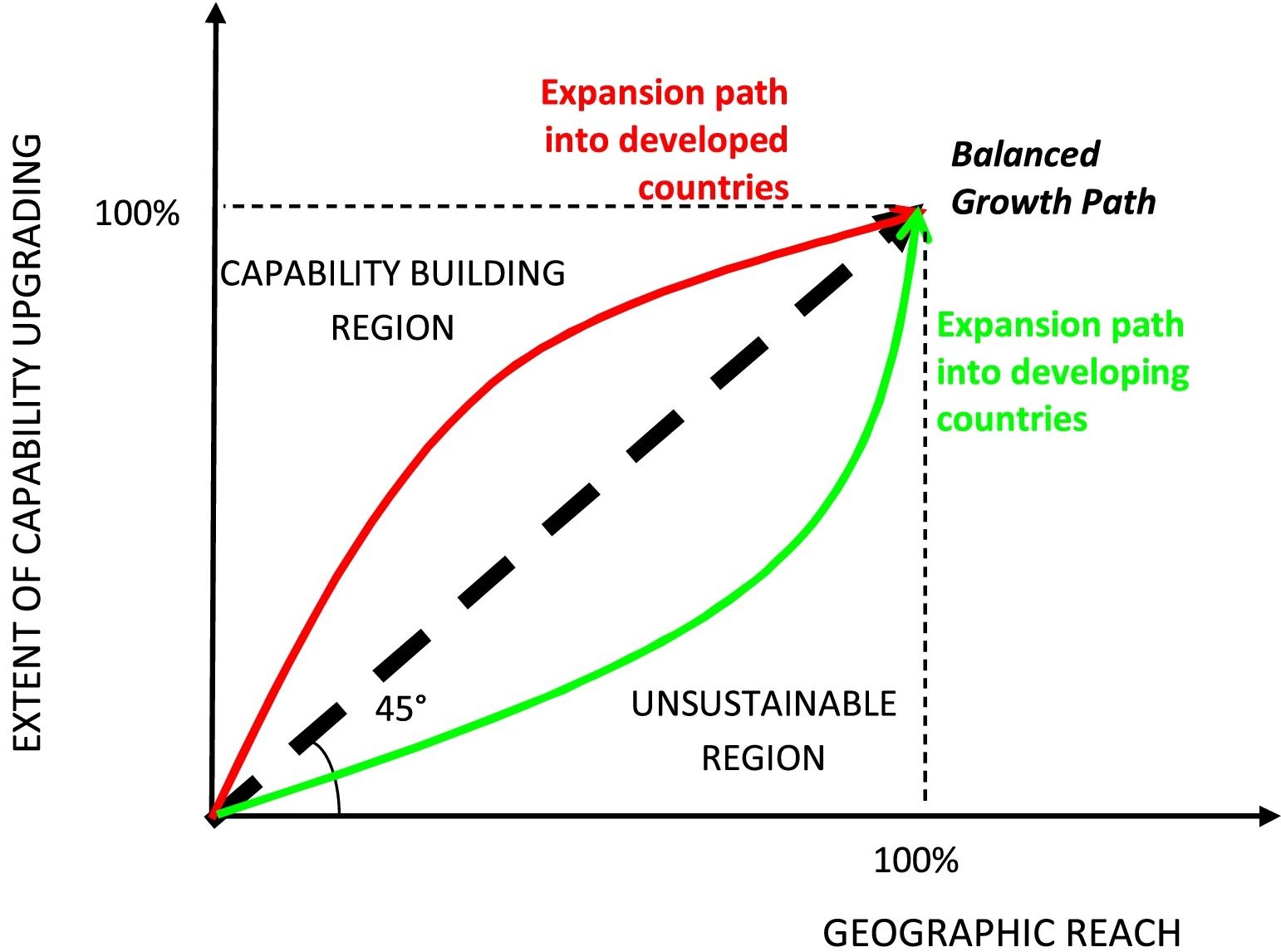

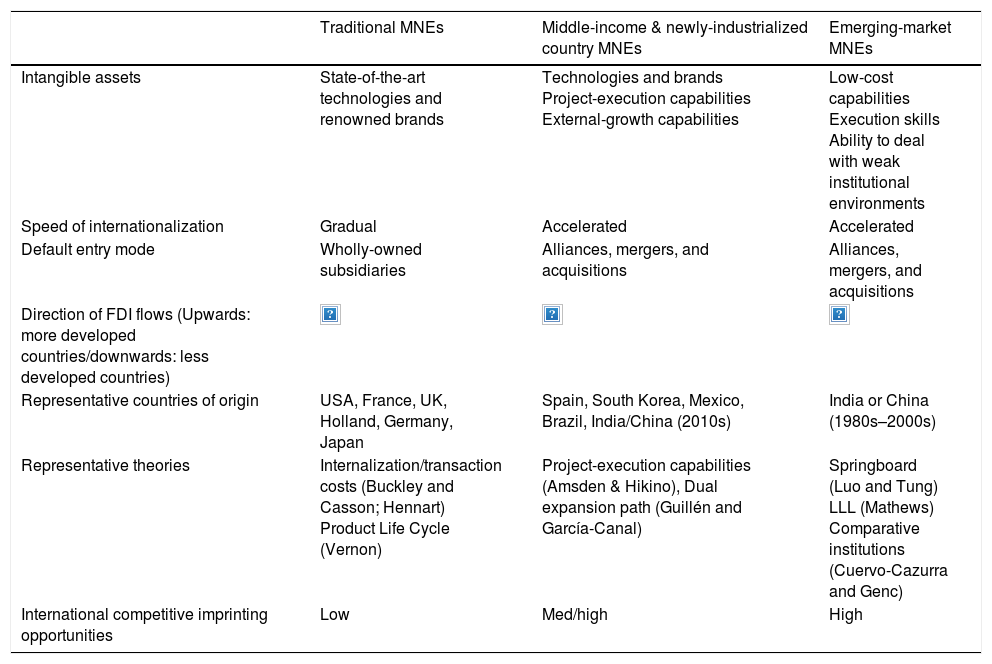

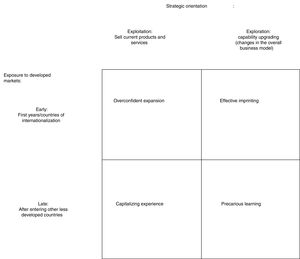

The risk-return tradeoff associated with the exposure to developed markets illustrates a significant dilemma that new multinationals face when expanding abroad. On the one hand, firms want to speed up the process of international expansion. On the other hand, they also need to upgrade capabilities and enhance their business model and their competitive advantage to increase their chances of success. That is why firms lacking strong competitive advantages, like emerging-market multinationals, follow a dual path in their international expansion, one path for the expansion into developed countries and another for developing ones (Guillén and García-Canal, 2009). They can expand aggressively into other emerging or developing countries, relying on the competitive advantages developed in their home country. However, they also need to enter developed countries to develop their capabilities by exposing themselves to state of the art technologies and customers. This dilemma is illustrated in Fig. 2, which reflects the two purposes that firms may pursue in their international operations: upgrade their capabilities or gain geographic reach, or both. The diagonal illustrates a balanced growth path which is in line with orthodox views of the international expansion of gradual theories.

Expansion paths of new MNEs in developed and developing countries.

Fig. 2 illustrates the two regions in which a firm can position itself in its international expansion. Above the diagonal it enters a region of capability building. In it the number of countries entered (the geographic reach) is sacrificed in order to catch up with global industry leaders. Below the diagonal the firm enters an unsustainable region, as increasing global reach before improving international competitiveness reduces the odds of success in most markets. Guillén and García-Canal (2009) show that high growing firms solve this dilemma by following a differentiated expansion path into developing and developed countries. They expand into a few developed countries at the beginning of their international expansion, even at the cost of poor profits, to upgrade their capabilities. However, they also expand heavily into developing countries in order to build scale and gain operational experience.

In sum, new multinationals overcome the dilemma between the risks and returns of early exposure to developed countries by limiting the exposure to developed countries to the few locations where the most sophisticated demand is and where the most useful knowledge can be accessed. By doing so, they are able to enhance their product, routines and procedures, with the aim of improving the firm's international competitiveness. It is in these cases where the impact of the foreign environment can be more determinant in the firm's future and where it can be expected a strong imprinting effect and a greater impact of this imprinting in the firm's profits. In addition, the combination of developed and developing countries at the early stages of the international expansion of the firm facilitates the accumulation of a diverse set of knowledge that improves the firm's absorptive capacity and its dynamic capabilities for entering into further countries (Zhou and Guillén, 2015). Later in the process of international expansion and once filled the gap with the more sophisticated competitors, the firm is better prepared to expand aggressively into the remaining developed countries, as shown in Fig. 2. The previously mentioned case of Haier fits perfectly with this pattern. The company expanded in its early years through Asia and the USA, paving the way for the further expansion that led it to become the first white goods company in the world. This shows that it takes time for companies to assimilate the external influences before they can expand more aggressively into developed countries. Other white goods players from emerging markets such as MABE or Arcelick followed the same approach as Haier (Bonaglia et al., 2007). Hence, we argue that:Proposition 3 New multinationals exposed to selected developed markets during the early stages of their international expansion benefit more from this exposure than others entering aggressively in several developed countries at the same time.

As previously mentioned, prior research on imprinting suggests that it is at the early stages of the life cycle of an organization when imprinting becomes more intense, due to the lack of institutionalized structure and processes at this stage. For this reason, new multinationals that internationalize earlier in their history (actively and/or passively) are more likely to be influenced by the foreign environment, as it can leave a mark not only in some routines, but also on the firm's business model. This is an important difference, because the environment poses some constraints in the design of the business model (Amit and Zott, 2015), so the exposure to different environments can overcome some of these constraints (especially when it comes to upgrade their capabilities in resource-richer countries), while also forces the firm to learn how to deal with different environments at the same time. This ability to deal with different kind of environments can be a source of competitive advantage (Henisz, 2003).

For this reason, born-global firms (Rialp et al., 2005; García-Lillo et al., 2016) are more likely to be affected by imprinting than firms expanding abroad in later stages of their life cycle. Previous research on born global firms confirms this fact. Sapienza et al. (2006) suggest that firms that internationalize early develop a dynamic capability for the exploitation of business opportunities in foreign markets. They argue that the exposure to diverse environments contributes to imprint deeply this capability, making easier the adaptation to uncertain environments.

On the contrary, firms that expand abroad in later stages of their life cycle are less willing to be affected by imprinting as a consequence of their international expansion, precisely because their structure, processes, and capabilities were already imprinted prior to it. In effect, they have been already imprinted by the characteristics of their home-country environment and those of its founders. Thus, for this type of firms a tension exists between the home country and international imprinting effects. However, there is an exception, the so-called born-again global firms (Bell et al., 2001); i.e. firms approaching international markets in a process of change that makes them more susceptible to external influences and that also lead them to following an accelerated growth path. In these firms, the radical change opens a window for imprinting.

But, again, not all born-global or born-again global firms are equal. Oviatt and McDougall (1994) identify two relevant dimensions to classify these firms: on the one hand, the degree of internationalization of the value chain, and, on the other hand, the number of countries involved. Internationalization of the value chain is reduced when the activities involved are just logistics and distribution (export oriented born globals). In this case, the benefits of passive internationalization are lower. They would be high when procurement and manufacturing are also internationalized, giving rise to international startups. The other dimension is the number of countries involved: a few (one region or a limited set of countries) or many (several regions or global scope). This dimension clearly separates regional from global players. In fact, only a small fraction of born globals are truly global players (Lopez et al., 2009). Export oriented born globals are also usually labeled as international market makers, as they arise to serve customers with unsatisfied needs so far. Depending on the scope of their expansion they would be either regional exporters or global exporters. These market makers have the inconvenient that when lacking a clear competitive advantage, imitators can reduce substantially their margins. That is why Oviatt and McDougall (1994) highlight the importance of controlling a key resource for the development of both regional and global exporters. In the case of international startups, these firms have an additional source of competitiveness that can be difficult to imitate: their dynamic capabilities for doing international arbitrage to match the needs of their clients. Depending on the scope of their expansion they would be either regional startups or global startups. Due to their wider international scope and their ampler arbitrage opportunities associated to the dispersion of the value chain across many countries, the impact of imprinting can be stronger for the case of global startups. These firms are going to receive more feedback and will be enjoying more learning opportunities due to their wider exposition to different international environments. Perhaps the best example of arbitrage and learning opportunities in a global start up is Infosys, one of the Indian pioneers in the IT outsourcing industry. The company was created to exploit the opportunity associated to international wage differentials in engineers and programmers, thus selling consulting and software development services performed in India to companies in developed countries. Being in contact with these sophisticated clients required some local support services, which forced the company to be able to coordinate the work of teams based in different locations. This capability, developed during the early years of the company, facilitated the evolution of their business model toward the so-called global delivery model. Under this model, the company can undertake complex projects by assigning each task to the most efficient location. It can also work on a 24/7 basis, if needed, to speed up the development of the project (Guillén and García-Canal, 2013). Hence, we expect that:Proposition 4 New multinationals that are born global or born-again global firms benefit more from early exposure to developed markets than other types of new multinationals that expand globally in a gradual way. New multinationals that are global startups benefit more from the early exposure to developed markets than the other types of new multinationals that are also born-global firms.

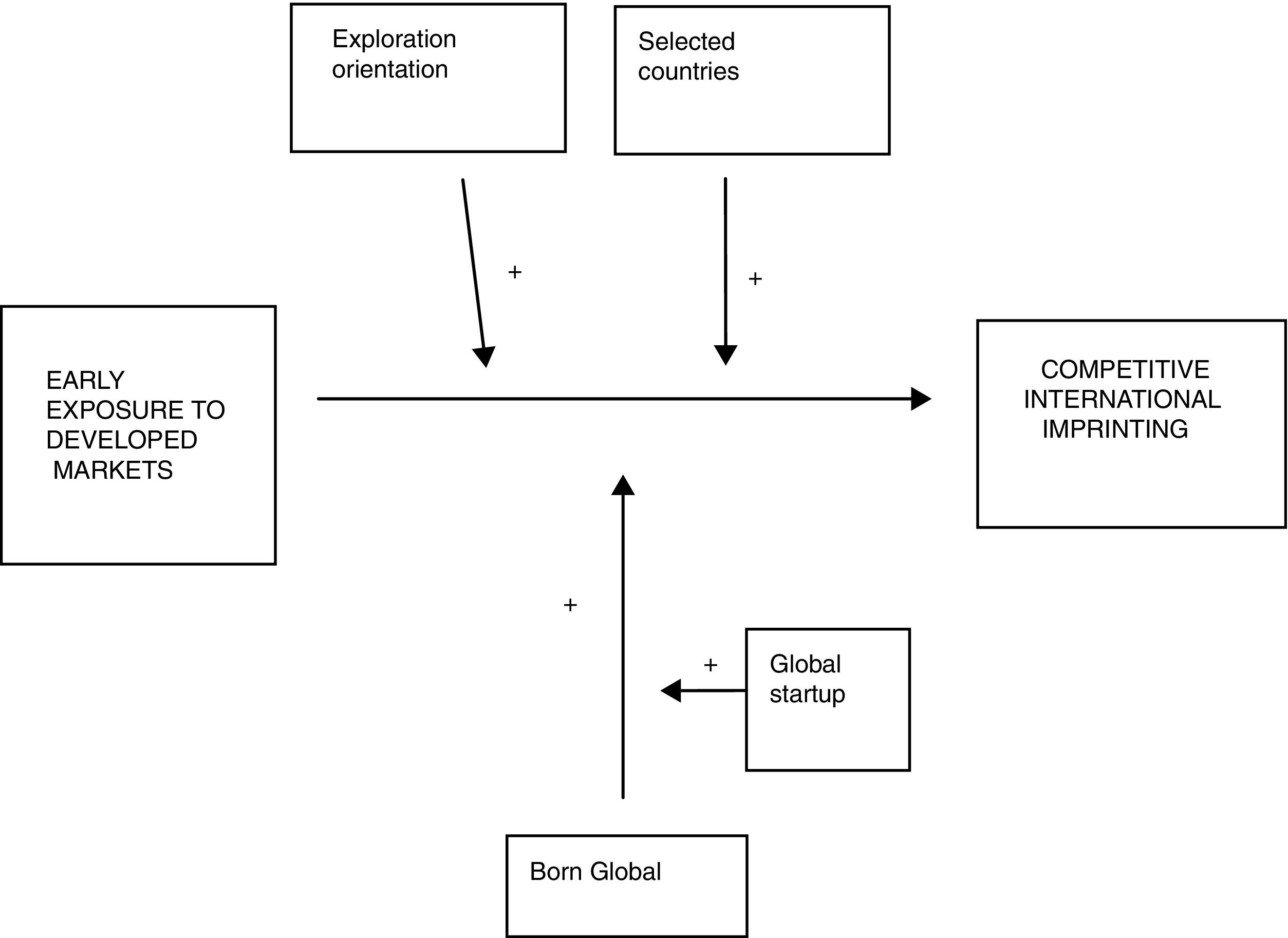

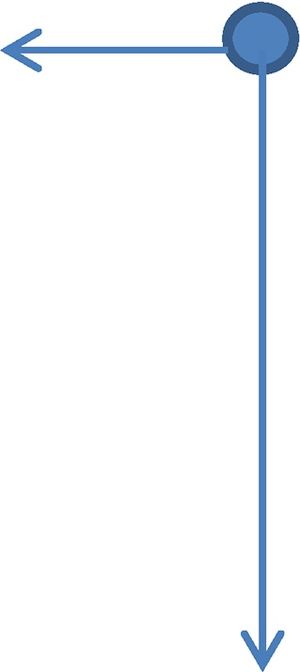

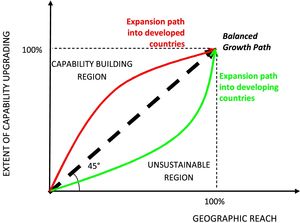

Our paper provides a theoretical framework to understand and explain the performance implications of an early exposure to developed markets by new multinationals. Taken as a whole, the propositions developed in our model show when and why the early exposure to developed markets by new multinationals increases the firm's international performance through a process of imprinting (Fig. 3). As previously mentioned, this early exposure to developed international markets entails a risk-return trade-off, and our framework shows the boundary conditions under which the benefits of this exposure outweigh its costs: a learning orientation, during critical stages of the lifecycle (e.g. the early years of the firm and/or of its international expansion), and limited to just a few countries. The essence of our model is that an early exposure to developed markets pays off when it is oriented to gain access to new knowledge and capabilities with the aim of transferring them to the entire organization and limiting the amount of the exposure in terms of financial commitment and economic risk.

An important issue pointed out in our model is the selection of the markets in which the firm aims to enter. They have to be carefully selected, as firms are not expected to enter indiscriminately into all developed markets, but just a few of them. These markets do not necessarily need to be the most developed countries, generally speaking, but the ones in which the most sophisticated competitors and customers are located. This is the main contribution of this paper to the literature on international imprinting: highlighting the importance of choosing the right country to be exposed to. Whereas previous research highlighted the importance of the ‘when’ (Sapienza et al., 2006), we focus on the importance of the ‘where’ and the ‘who’. Thus, our contribution to this literature is threefold. First, we show that not all international markets are equally important when it comes to international imprinting. Second, we highlight that the international competitive imprinting effect mostly takes place at the beginning of the international expansion, irrespective of the life cycle of the firm—although we acknowledge the relevance of international imprinting for born global firms. Three, we also highlight the importance of the ‘who,’ as we show that firms from middle income, newly industrialized and emerging countries (New Multinationals) are the ones that can make the most of international competitive imprinting effects.

Our paper adds to recent research showing the importance of considering cross-country differences in resources as a variable moderating the relationship between international diversification and performance. How a foreign country can contribute to the improvement of a firm's international competitiveness would be dependent on the availability and sophistication of local resources. That is why there is always a tradeoff between short and long-term profitability when investing in resource richer countries. Kim et al. (2015) show that when new multinationals expand to resource poorer countries internationalization and performance have always a positive relationship, whereas when expanding to resource richer countries internationalization and performance have a U-shaped relationship. Consistent with them, we argue that despite the short term possible negative consequences in performance, expanding to developed countries can be considered an investment to reinforce the firm competitiveness in all countries. However, our paper also contributes to this literature by showing the importance of an early exposure at the beginning of the process of international expansion due to the importance of imprinting. Expanding into resource richer countries later would imply that inertia and resistance to change could hamper the assimilation and dissemination through the entire corporation of the resources and learning acquired in developed countries. In any case, our paper also shows the importance of considering the degree of development of home and host countries to explain the relationship between internationalization and performance.

A missing question in our paper is the “how”, i.e. the most appropriate entry mode when it comes to international imprinting. Firms can use a number of entry modes to become exposed to foreign countries. Exporting is perhaps the simplest way to expand abroad, as it does not necessarily require expanding the firm's productive capacity since the firm sells overseas home country manufactured goods. Even though the distance between the operations and the final market can reduce the possibilities to learn and adapt, there is a large literature that highlights how firms can learn from exporting (Clerides et al., 1998; Salomon et al., 2005; Greenaway and Kneller, 2007). There is also evidence documenting the role of learning by importing and outsourcing; so passive internationalization can also be a way through which the international environment can leave a mark in the firm (Wagner, 2011; Maskell et al., 2007). Fernández Pérez et al. (2017) documented how the success of a leading pharmaceutical company from Spain (Laboratorios Ferrer) was cemented by their origins as an importer of pharmaceutical products, through which they developed international networking capabilities. Grifols, another pharma company from Spain, also benefited from the founder's personal connections with doctors, technicians and scientists from Germany (Fernández Pérez et al., 2017). Obviously, entry modes based on foreign direct investment have more potential for learning and gaining access to foreign resources. When expanding through foreign direct investments, learning opportunities are higher (Kogut and Zander, 1993), but at the expense of more risks due to the higher amount of resources committed. For this reason, the right entry mode used to the exposure to developed markets may vary.

Our theoretical framework also contributes to the knowledge-based theory of the multinational enterprise (Kogut and Zander, 1993; Grant, 1996). Recent developments on this field focus on the role of MNEs as knowledge integrators (Madhok, 2015) and the factors that hinder the integration of external knowledge (Narula, 2014). Whereas inertia is normally the factor used to explain the growing inability of MNEs to integrate new knowledge as the firm gains in complexity, we believe that the timing of the exposure to developed markets by New Multinationals can explain also the openness to external knowledge by MNES. An early exposure to developed countries coupled with the exposure to other less developed countries increases the firm's absorptive capacity, as the diversity of international experience increases (Zhou and Guillén, 2015). In fact, García-García et al. (2017) recently found that firms with a diverse international experience are better equipped to speed up their internationalization process than firms with more homogeneous previous experience. This evidence suggests that, as part of the imprinting effect associated to the early exposure to developed countries at the beginning of the international expansion, firms develop a dynamic capability to deal with different environments at the same time.

Our paper contributes to recent research and theory development in the fields of new and emerging market multinationals. We believe that incorporating imprinting into this area of research helps explain why the leading new multinationals have been able to grow at a high speed and why only a selected group of firms in each middle income or emerging country have been able to succeed in the global arena. First, we contribute to link the literature of new multinationals with the one of born-again global firms. Anecdotal evidence on the new multinationals (see for instance Guillén and García-Canal, 2010; Guillén and García-Canal, 2013) suggests that these firms have started to expand abroad after a strategic change. Many new multinationals could be considered born-again global firms, something that would explain why these firms were so receptive to external influences at the beginning of their international expansion, and, thus, able to grow so quickly.

Secondly, our framework explains why not all firms from middle income or emerging countries exposed to developed ones can become a successful NMNE. Consistently with Hennart (2012), we argue that the recent success of the new multinationals is grounded on the combination of specific advantages developed in their home country with other resources and knowledge gained in developed countries. Obviously, the home country exerts an important influence on foreign location choice decisions, making it easier for these firms to expand to other developing countries (Cuervo-Cazurra and Genc, 2008; Cuervo-Cazurra, 2011; Narula, 2015; Elia and Santangelo, 2017). However, avoiding developed markets in the early stages of internationalization can limit the outcomes of the firm's internationalization process. Our framework highlights that not all firms in middle income or emerging countries can challenge the position of established multinationals, not only because they need some advantage of their own developed in their home country, but also because they need to be exposed to the right countries at the right time and with the right attitude just to profit from the competitive benefits of imprinting. In other words, firms also need to have a learning strategy to gain and exploit knowledge and capabilities to improve their international competitiveness. Even though a detailed analysis of the elements of this strategy would fall beyond the scope of this paper, future research could analyze the implications of these learning strategy in terms of clustering (Shaver and Flyer, 2000; Wang et al., 2014), partner selection (Hitt et al., 2000; Baum et al., 2010), alliance management (Kale et al., 2002; Schilke and Goerzen, 2010), ownership structure (Puig et al., 2009), or knowledge management (Argote and Miron-Spektor, 2011). These and other avenues for future research would further enhance the usefulness of using the concept of imprinting.

The authors thank the comments of the editor and reviewers, Raquel García-García and seminar participants at Universidad de Barcelona; as well as the financial support from the First Fellowships for Research Projects in the Socio-Economic Sciences of Fundación BBVA 2014–2016.

There is a debate regarding whether new approaches are needed to explain the international expansion of Emerging Market Multinationals (see Cuervo-Cazurra, 2012; Ramamurti, 2012). In fact, prominent scholars in the traditional approaches have recently defended the applicability of these approaches to Emerging Market Multinationals. See, for instance, Narula (2012) or Verbeke and Kano (2015).