Introduction. Identifying liver fibrosis is important to evaluate the severity of liver damage and to establish a prognosis. Utility of non-invasive markers of liver fibrosis has been proved in adults but there are few reports in children. The aim of this study was to evaluate Fibrotest® score and APRI suitability to identify children with liver fibrosis.

Material and methods. 68 children with chronic liver disease requiring liver biopsy were prospectively included from three 3rd-level pediatric hospitals. The same pathologist evaluated all liver biopsies; fibrosis degree was determined by METAVIR score. Serum samples were obtained to determine Fibrotest® and APRI. AUROC were used to determine cut-off and differentiate between advanced fibrosis (METAVIR F3, F4) and no fibrosis (F0).

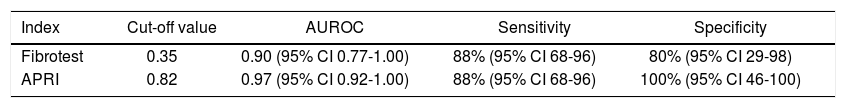

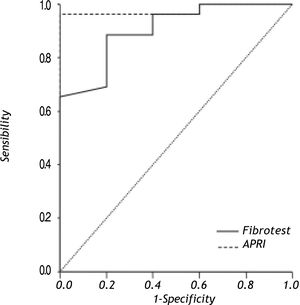

Results. 68 biopsies were evaluated; METAVIR > F3 was identified in 26 (38%). Non invasive liver fibrosis markers to differentiate between advanced and no fibrosis were: Fibrotest® AUROC = 0.90 (95% CI 0.77-1.00) (cut-off value 0.35) sensitivity 88.00% (95% CI 68-96) and specificity 80% (95% CI 29-98); and for APRI AUROC = 0.97 (95% CI 0.92-1.00) (cut-off value 0.82), sensitivity 88% (95% CI 68-96) and specificity = 100% (95% CI 46-100).

Conclusion. These results suggest the utility of Fibrotest® and APRI to identify advanced fibrosis; they can be recommended to select patients for liver biopsy and during patient follow-up.

Chronic liver disease (CLD) in children varies with age of presentation and differences in their natural history; the main causes in newborn and young infant are idiopathic neonatal hepatitis, biliary atresia and metabolic disease. In older children and adolescents, the leading causes are autoimmune hepatitis, cryptogenic cirrhosis, biliary atresia post-Kasai status, primary sclerosing cholangitis, Wilson’s disease, chronic hepatitis B (HBV), hepatitis C (HCV), and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).1,2 These different etiologic forms of CLD have a common histopathological pathway that is the formation and accumulation of fibrosis leading to the development of progressive distortion of hepatic architecture and cirrhosis. Natural history studies indicate that advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis in children at diagnosis are 69% in those with autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) type I, 38% in AIH type 2, 21% in Wilson disease, 25% in patients with HCV, 3.5% in children with HBV and 3% in cases with NAFLD.3–7 Progression may take years, particularly for those patients with chronic viral hepatitis or NAFLD who are well compensated without clinical or laboratory signs of cirrhosis, therefore, staging of hepatic fibrosis is of clinical importance for diagnostic assessment and to decide the need for immediate therapy or whether to include the patient in a liver transplantation program.

The histopathological study of the liver has been the gold standard for grading and staging liver disease; however, liver biopsy has some disadvantages, such as sampling error and inter-observer variability;8 it is an invasive method with potential complications in children, with the occurrence of bleeding (2.8%), biliary leaks (0.6%) pneumothorax (0.2%), and mortality in up to 0.6% of cases.9–11 In recent years, there has been increasing interest in the possibility of identifying liver fibrosis by using the non-invasive markers measured in peripheral blood. Many studies have reported the use in adult patients of strategies such as Fibrotest® and aspartate transaminase to platelets ratio index (APRI). These serum makers have been validated in adults, although there are few reports in children.12–16 The aim of this study was to evaluate the use of Fibrotest® score and APRI to identify children with liver fibrosis, as compared with liver biopsy specimens.

Material and MethodsThree 3rd-level pediatric hospitals in Mexico participated in the study. All consecutive children who underwent a liver biopsy for the assessment of CLD, independent of the study, were prospectively included. Patients with hemolysis and Gilbert disease were excluded.

A blood sample (5 mL) was drawn for the determination of the biochemical parameters, including aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), total bilirubin, platelet count, prothrombin time, albumin, alpha2-macroglobulin, apolipoproteinA1, and haptoglobin. Clinical data included age, gender, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), evaluation of liver and spleen size.

Serum samples for the Fibrotest® score (Biopredictive, Paris, France)17 were assessed according to the laboratory recommendations. Values of Fibrotest® range are from zero to 1.00 with higher values indicating a greater probability of significant fibrosis.

APRI index was calculated as:18

[(AST UI/L/AST UI/L superior normal limit) x100]/Platelets counts (109 /L).

Liver biopsy was performed either percutaneously using the Menghini technique or by laparotomy with deep cuneiform subcapsular specimens. Liver specimens were fixed in buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. The tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin, Masson trichrome and reticulin stains for the evaluation of fibrosis and analyzed by the same pathologist blinded to the results of serum markers.

All biopsies were evaluated at least for a total of 10 portal tracts. Necro-inflammatory activity was assessed as mild, moderate and severe; fibrosis was evaluated by the METAVIR score as no fibrosis (F0), portal fibrosis (F1), portal fibrosis with some septal fibrosis (F2), portal fibrosis with more septal fibrosis (F3) and cirrhosis (F4).19

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board; study procedures were performed in all children only after written informed consent was obtained from parents.

AnalysisResults are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and significance was set at p < 0.05 for all tests. The biochemical markers to detect Fibrosis® stage was assessed by the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve to determine cut off and differentiate between different grades of fibrosis and no fibrosis.

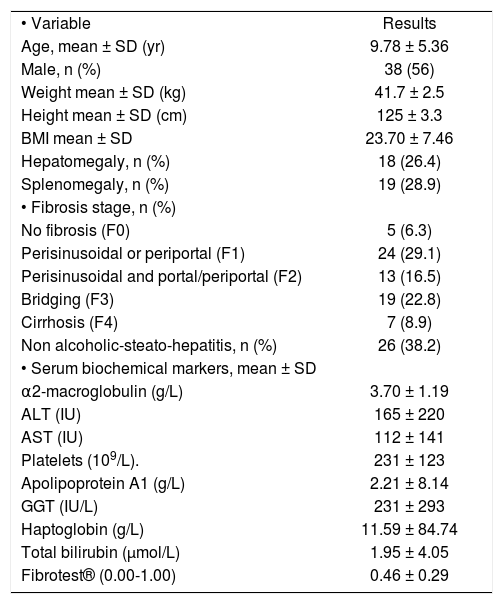

ResultsFrom February 2008 through February 2010, 68 patients were included. The characteristics of the children are summarized in table 1. There were 38 boys (56%) and 30 girls (44%) mean age was 9.6 ± 2.3 years (from 1 to 17 years). The etiology was NAFLD in 26 (38.2%) cases, AIH in 16 (23.5%) biliary atresia post-Kasai status in 12 (17.6%), idiopathic hepatitis in 6 (8.8%), drug toxicity in 5 (7.4%), metabolic diseases (Wilson disease and Tyrosinemia) 2 (3.0%) and in one HCV (1.5%).

Clinical characteristics of 68 children with chronic liver diseases.

| • Variable | Results |

| Age, mean ± SD (yr) | 9.78 ± 5.36 |

| Male, n (%) | 38 (56) |

| Weight mean ± SD (kg) | 41.7 ± 2.5 |

| Height mean ± SD (cm) | 125 ± 3.3 |

| BMI mean ± SD | 23.70 ± 7.46 |

| Hepatomegaly, n (%) | 18 (26.4) |

| Splenomegaly, n (%) | 19 (28.9) |

| • Fibrosis stage, n (%) | |

| No fibrosis (F0) | 5 (6.3) |

| Perisinusoidal or periportal (F1) | 24 (29.1) |

| Perisinusoidal and portal/periportal (F2) | 13 (16.5) |

| Bridging (F3) | 19 (22.8) |

| Cirrhosis (F4) | 7 (8.9) |

| Non alcoholic-steato-hepatitis, n (%) | 26 (38.2) |

| • Serum biochemical markers, mean ± SD | |

| α2-macroglobulin (g/L) | 3.70 ± 1.19 |

| ALT (IU) | 165 ± 220 |

| AST (IU) | 112 ± 141 |

| Platelets (109/L). | 231 ± 123 |

| Apolipoprotein A1 (g/L) | 2.21 ± 8.14 |

| GGT (IU/L) | 231 ± 293 |

| Haptoglobin (g/L) | 11.59 ± 84.74 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 1.95 ± 4.05 |

| Fibrotest® (0.00-1.00) | 0.46 ± 0.29 |

Presentation was subclinical in 27 (39%) (all the cases with NAFLD and one with chronic HCV); 35 (51%) had persistent transaminasemia as a single finding. During the initial evaluation, 42 cases (61%) had hepatomegaly, 18 (26%) splenomegaly, 19 (28%) liver discompensation data including: 10 (15%) with ascites, 9 (13%) variceal bleeding, 7 (10%) secondary hypersplenism (thrombocytopenia < 100.000 platelets) and 5 (7.3%) coagulopathy with an INR > 2. The patients had mean serum ALT 165 IU/L and AST 112 IU/L.

Laparoscopic liver biopsies were done in 42 cases and needle biopsies in 26; at least 10 portal tracts were examined in each liver specimen.

According to METAVIR score, fibrosis stage was: F0 in 5 cases, F1 in 24, F2 in 13, F3 in 19 and F4 in 7. Necro-inflarnmatory activity was mild in 32, moderate in 24, severe in 10 and absent in 2.

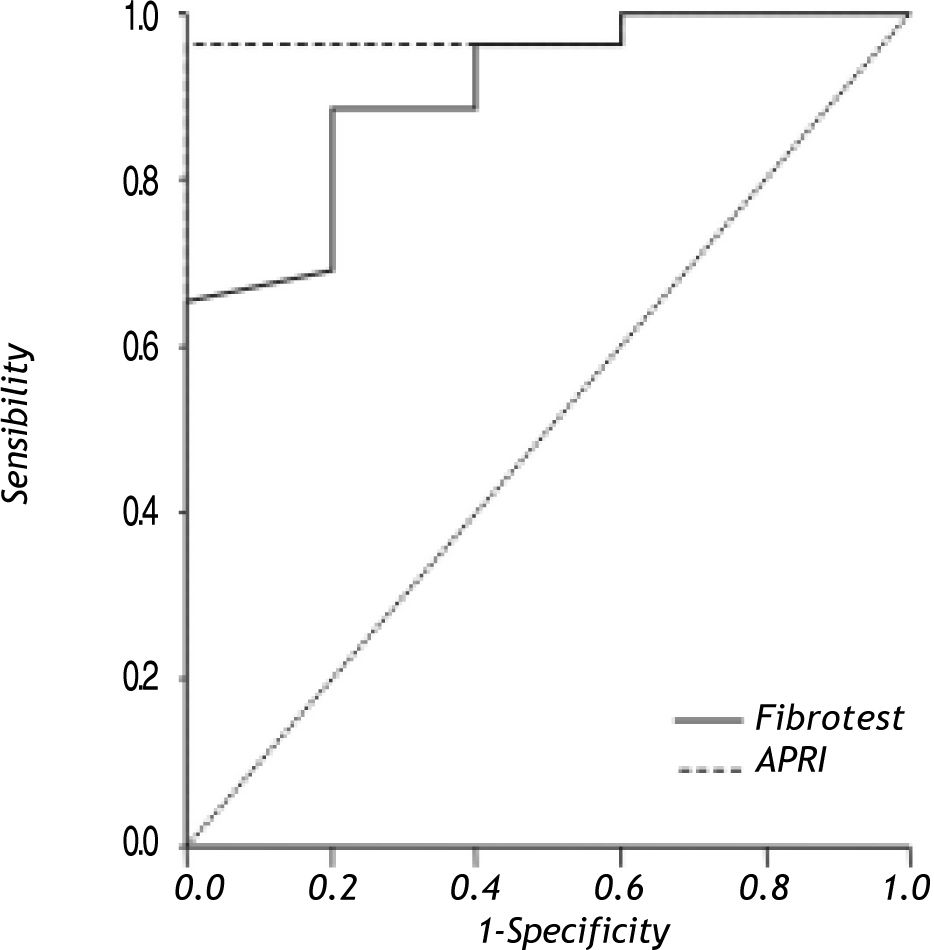

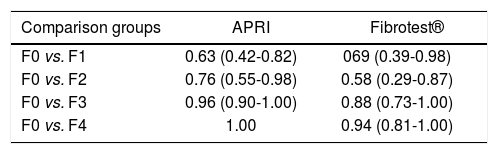

Results of AUROC to differentiate between different degrees of fibrosis and no fibrosis with Fibrotest® and APRI are shown in table 2; results of non-invasive liver fibrosis markers to differentiate between advanced fibrosis (METAVIR > F3) and no fibrosis (METAVIR F0) are shown in figure 1. The Fibrotest® and APRI AUROC were 0.90 (cut-off value of 0.35) and 0.97 (cut-off value 0.82), respectively. Fibrotest® and APRI sensibility was 88 and 88% with a specificity of 80 and 100%, respectively (Table 3).

Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve to differentiate between grades of fibrosis and no-fibrosis.

| Comparison groups | APRI | Fibrotest® |

|---|---|---|

| F0 vs. F1 | 0.63 (0.42-0.82) | 069 (0.39-0.98) |

| F0 vs. F2 | 0.76 (0.55-0.98) | 0.58 (0.29-0.87) |

| F0 vs. F3 | 0.96 (0.90-1.00) | 0.88 (0.73-1.00) |

| F0 vs. F4 | 1.00 | 0.94 (0.81-1.00) |

Non-invasive liver fibrosis markers to differentiate between advanced (> F3) and no fibrosis.

| Index | Cut-off value | AUROC | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fibrotest | 0.35 | 0.90 (95% CI 0.77-1.00) | 88% (95% CI 68-96) | 80% (95% CI 29-98) |

| APRI | 0.82 | 0.97 (95% CI 0.92-1.00) | 88% (95% CI 68-96) | 100% (95% CI 46-100) |

The study confirms that fibrosis is a scarring response that occurs in almost all patients with chronic liver injury (92% in this study, at the time of liver biopsy). Liver fibrosis leads to cirrhosis and all the complications of end-stage liver disease, including portal hypertension, ascites, encephalopathy, synthesis dysfunction, and impaired metabolic capability. There are multiple causes that progress to CLD and cirrhosis such as: viral hepatitis C and B, AIH and metabolic diseases. Recently NAFLD has been reported to be the cause of CLD especially in Hispanic children;20 it is probable that for this reason NALFD group represented the major group in our cases.

In this study we evaluate the Fibrotest® score and APRI to identify children with liver fibrosis due to CLD; our results showed that these non-invasive markers can differentiate between no-fibrosis from significant fibrosis. Both markers are based on blood tests, most of them routinely performed in patients with liver diseases with no need for additional blood collection. Although there are other non-invasive studies known as direct markers of liver fibrosis (tenascin, hyaluronan, collagen VI, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinasel or TIMP-1) based on biochemical parameters directly linked to fibrogenesis the limitation is that they are not routinely available in all hospital settings.21

Fibrotest® has been validated in adults and involves assessment of α2 macroglobulin, haptoglobin, apolipoprotein Al, GGT, and total bilirubin. Results from each test are formulated to determine three categories of fibrosis: mild (METAVIR F 0-1), significant (METAVIR F2-4), or indeterminate.22

In our study, detection of fibrosis (F3 + F4) with Fibrotest®, the AUROC was of 0.90, sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 80%. In one study where similar results were reported in 116 children with chronic liver disease for the diagnosis of cirrhosis due to different etiologies, the AUROC was 0.73, and 0.73 for Fibrotest® and APRI, respectively.15

APRI was introduced by Wai, et al.,18 who combined aspartate aminotrasferase (AST) levels with platelet count. This index was assessed in several studies of adult patients with hepatitis C and showed an AUROC range from 0.77 to 0.94 to detect cirrhosis.23,24 The differences in the results in these studies may be due to the severity of the liver disease and related to the AST and platelet count reference values. The AUROC for the diagnosis of severe fibrosis detected by APRI in the present study was 0.97 (cut-off value for AST 40 UI).

These non-invasive markers have been validated as well in specific CLD; in 50 children with HCV, Fibrotest® showed an AUROC of 0.97 to discriminate between mild and advance fibrosis.14 Another study in 26 HIV-1 vertically infected children, abnormal Fibrotest® and APRI were reported in 15 (63%) and 5 (21%) cases, respectively.25 In pediatric population, non-invasive serum markers have been assessed in few studies with different accuracy for the diagnosis of fibrosis; more studies in children that include a major number of patients will need to be done in order to establish the real value of these tests.

The main limitation of this study is the small number of patients included with different etiologies; this factor may provoke bias during the cut-off analysis for each biomarker, and the specificity and sensitivity of these tests may be different depending in the etiology of the CLD.

ConclusionIn conclusion, Fibrotest® and APRI in our study, which included a limited number of patients with different etiologies, demonstrated their utility to predict advanced fibrosis in children with CLD. They can be used as a screening test to select patients for liver biopsy, especially in those with subclinical features and during follow-up.

Abbreviations- •

AIH: autoimmune hepatitis.

- •

ALT: alanine aminotransferase.

- •

APRI: aspartate transaminase to platelets ratio index.

- •

AST: aspartate aminotransferase.

- •

AUROC: area under receiver operating characteristics curve.

- •

CLD: chronic liver disease.

- •

GGT: gamma glutamyl transpeptidase.

- •

HBV: hepatitis B virus.

- •

HCV: hepatitis C virus.

- •

NAFLD: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.