Background. Acute hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection in solid organ transplant recipients is rare, but can cause severe hepatic and extrahepatic complications. We sought to identify the pretransplant prevalence of HEV infection in heart and kidney candidates and any associated risk factors for infection.

Material and methods. Stored frozen serum from patients undergoing evaluation for transplant was tested for HEV immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies and HEV RNA. All patients were seen at Mayo Clinic Hospital, Phoenix, Arizona, with 333 patients evaluated for heart (n = 132) or kidney (n = 201) transplant. HEV IgG antibodies (anti-HEV IgG) were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and HEV RNA by a noncommercial nucleic acid amplification assay.

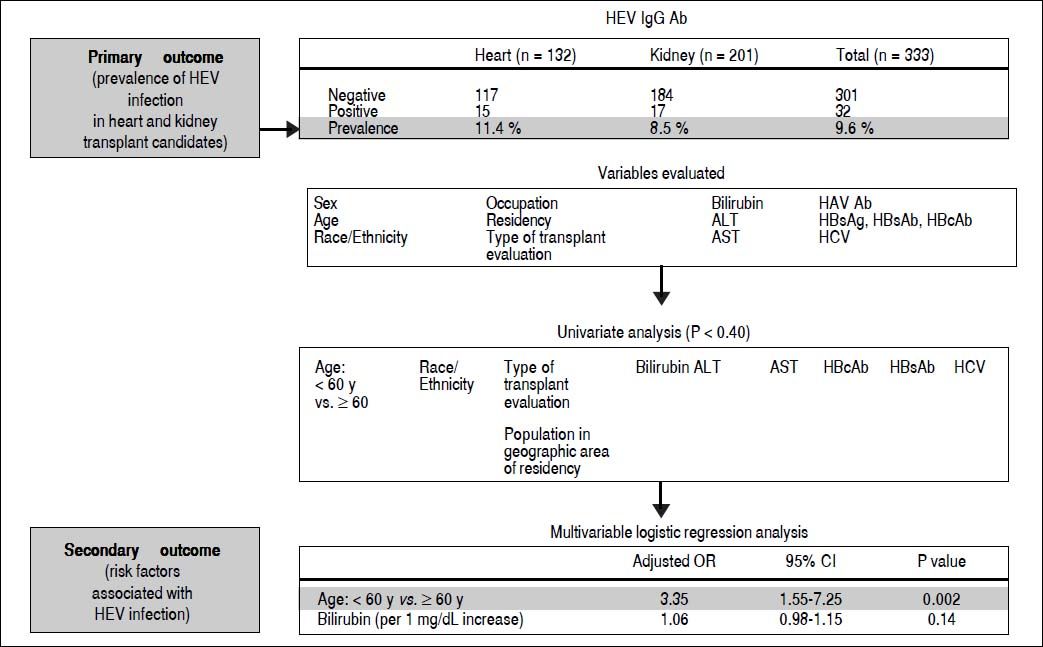

Results. The prevalence of anti-HEV IgG was 11.4% (15/132) for heart transplant candidates and 8.5% (17/201) for kidney transplant candidates, with an overall seroprevalence of 9.6% (32/333). None of the patients tested positive for HEV RNA in the serum. On multivariable analysis, age older than 60 years was associated with HEV infection (adjusted odds ratio, 3.34; 95% CI, 1.54-7.24; P = 0.002).

Conclusions. We conclude that there was no evidence of acute HEV infection in this pretransplant population and that older age seems to be associated with positive anti-HEV IgG.

Solid-organ transplant (SOT) recipients are a population at risk for development of severe complications associated with hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection that include acute and chronic hepatitis, graft dysfunction and cirrhosis.

In SOT recipients, chronic HEV can develop in 60 to 80% of patients, with acute infection.1–3 Accelerated progression of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis also has been reported in approximately 15% of patients.1 Most of these patients have been described in locally acquired HEV infection secondary to genotype 3.4 Recent evidence demonstrates that monotherapy with ribavirin is effective to achieve sustained virologic response after 3 months of therapy in 78% (46/59) of SOT recipients with acute HEV infection.5

In a series of 274 heart transplant recipients, the anti-HEV immunoglobulin G (IgG) seroprevalence was 11% (31/274), compared with 2% (11/537) in healthy controls, and the prevalence of chronic infection was 2% (4/274).6 In contrast, the reported prevalence of chronic infection in kidney transplant patients may be as high as 80% (12/15).7

In the US general population, the anti-HEV IgG seroprevalence has been reported as high as 21% (3,925/18,695), with a higher prevalence in men, non-Hispanic whites, Midwest residents, and metropolitan residents.8 However a recent study using a high performance assay reported a much lower seroprevalence of 6% (529/8,814).9 Risk factors associated with positive seroprevalence include pet ownership and consumption of organ meats such as liver.8,10 In a French study of HEV infection in SOT recipients, the only risk factor associated with HEV infection was consumption of wild game.3

The cost benefit of routine pretransplant screening for HEV infection remains to be defined. Data are also limited on the prevalence of HEV infection in the pretransplant population in SOT candidates.

Pretransplant seroprevalence has been evaluated in 700 kidney and liver transplant recipients screened on the day of their transplant.10 Positive anti-HEV IgG and anti-HEV immunoglobulin M (IgM) were found in 14% (99/700). No association between demographic or clinical factors and HEV serum antibodies was identified, and none of the patients tested positive for HEV RNA.

We evaluated serum from heart and kidney transplant candidates in our tertiary care center as part of the pre-transplant evaluation. The main outcome of our study was to identify the prevalence of serum anti-HEV IgG and HEV RNA in heart and kidney transplant candidates.

Material and MethodsPatientsWe evaluated 337 adult heart and kidney transplant candidates for anti-HEV IgG antibodies and HEV RNA at Mayo Clinic Hospital, Phoenix, Arizona, between March 1, 2011, and August 31, 2013. Mayo Clinic Arizona is part of the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) region 5 that includes Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico and Utah. Most of the heart and kidney candidates had residence in the west of the United States. The number of patients that was born in other countries was not analyzed, however historically the transplant population served at Mayo Clinic Arizona is mainly from US born citizens with a very few number of patients from other countries which is limited by UNOS regulations.

Archived frozen serum was tested, all patients were older than age 18 years, and informed consent was obtained for clinical evaluation prior to transplant. The study protocol had approval from the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. Demographic and clinical characteristics were obtained from the electronic medical record for each patient (Figure 1).

Summary of study results and outcomes of the pretransplant prevalence of hepatitis e virus infection in a solid-organ transplant population of 333 patients. None of the 333 patients included in the analysis tested positive for hepatitis E virus RNA in the serum. Ab: indicates antibody. ALT: alanine aminotransferase. AST: aspartate aminotransferase. HAV Ab: hepatitis A virus antibody. HBcAb: hepatitis B core antibody. HBsAb: hepatitis B surface antibody. HBsAg: hepatitis B surface antigen. HCV: hepatitis C virus. HEV: hepatitis E virus. HEV IgGAb: hepatitis E virus IgG immunoglobulin G antibody. OR: odds ratio. y: years.

A commercially available qualitative in vitro enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect IgG antibodies against HEV (recomWell; Mikrogen; Neuried, Germany) was used. This test is based on the principle of an indirect sandwich ELISA and can identify antibodies against HEV genotypes 1 and 3. A positive result indicates a previous or an active primary infection. A qualitative in vitro nucleic acid assay system for the detection of HEV RNA in serum was used (Procleix HEV Assay; Hologic Gen-Probe Inc, San Diego, CA). This assay is currently under development and is not available for commercial use. The assay involves 3 main steps:

- •

Sample preparation using a magnetic-based specific target capture method.

- •

HEV RNA target amplification by transcription-mediated amplification, and

- •

Detection of the amplification products (amplicon) using chemiluminescent nucleic acid probes.

Development data indicate that the assay has a 95% limit of detection of approximately 10 IU/mL (HEV World Health Organization [WHO] Standard 6329/10) and is capable of detecting the 4 known HEV genotypes with similar sensitivity. Preliminary testing showed specificity of 99.95%. A positive result indicates active infection.

Sera from 337 heart and kidney transplant candidates were tested using the Procleix HEV assay on the fully automated Procleix Panther System (nucleic acid test system) for the presence of HEV RNA. The serum samples were initially collected for anti-HLA antibody screening tests routinely performed on all SOT candidates, had been retained frozen (−80°C) for the required period of time, and were ready to be discarded. The approximate volume of the samples was between 1 and 2 mL. Samples were transferred to proprietary tubes designed for low-volume samples and barcoded for tracking and data analysis. Samples were then run on the Procleix Panther System using a research-use-only notebook lot of the reformulated Procleix HEV assay reagent kit. For complete testing, a total of 2 runs was performed. Appropriate negative calibrators and positive calibrators (in vitro transcript of HEV 3a whose sequence was derived from the HEV WHO Standard 6329/ 10 [nucleotide sequence]) were included in each run. After a run, the result reports were printed and the raw data were exported for further analysis using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, Washington) software.

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics were used to summarize patient demographic and clinical characteristics. Median and range were reported for continuous variables, and count and percentage were reported for nominal variables. Characteristics were compared by type of transplant (heart or kidney) and by negative or positive anti-HEV IgG using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test or the χ2 test. Possible factors associated with HEV infection were evaluated by applying logistic regression to model the probability of positive anti-HEV IgG. For the univariate analysis comparing positive and negative anti-HEV IgG, a variable with P < 0.40 was considered in the multivariable model. The higher cutoff for significance was chosen because of the small sample size for those with positive anti-HEV IgG. Backward elimination was conducted to select the set of variables, and any variable with P < 0.15 was retained in the model. The adjusted odds ratios (ORs), the corresponding 95% CIs, and P values were reported. All analyses were performed in SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc). Two-sided tests were used, and statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

ResultsWe studied 337 heart and kidney transplant candidates to determine the prevalence of HEV infection. Four patients were excluded from analysis because of duplicated or missing clinical data. We therefore evaluated demographic characteristics and routine laboratory tests of 333 patients (132 heart and 201 kidney) (Tables 1 and 2; Figure 1).

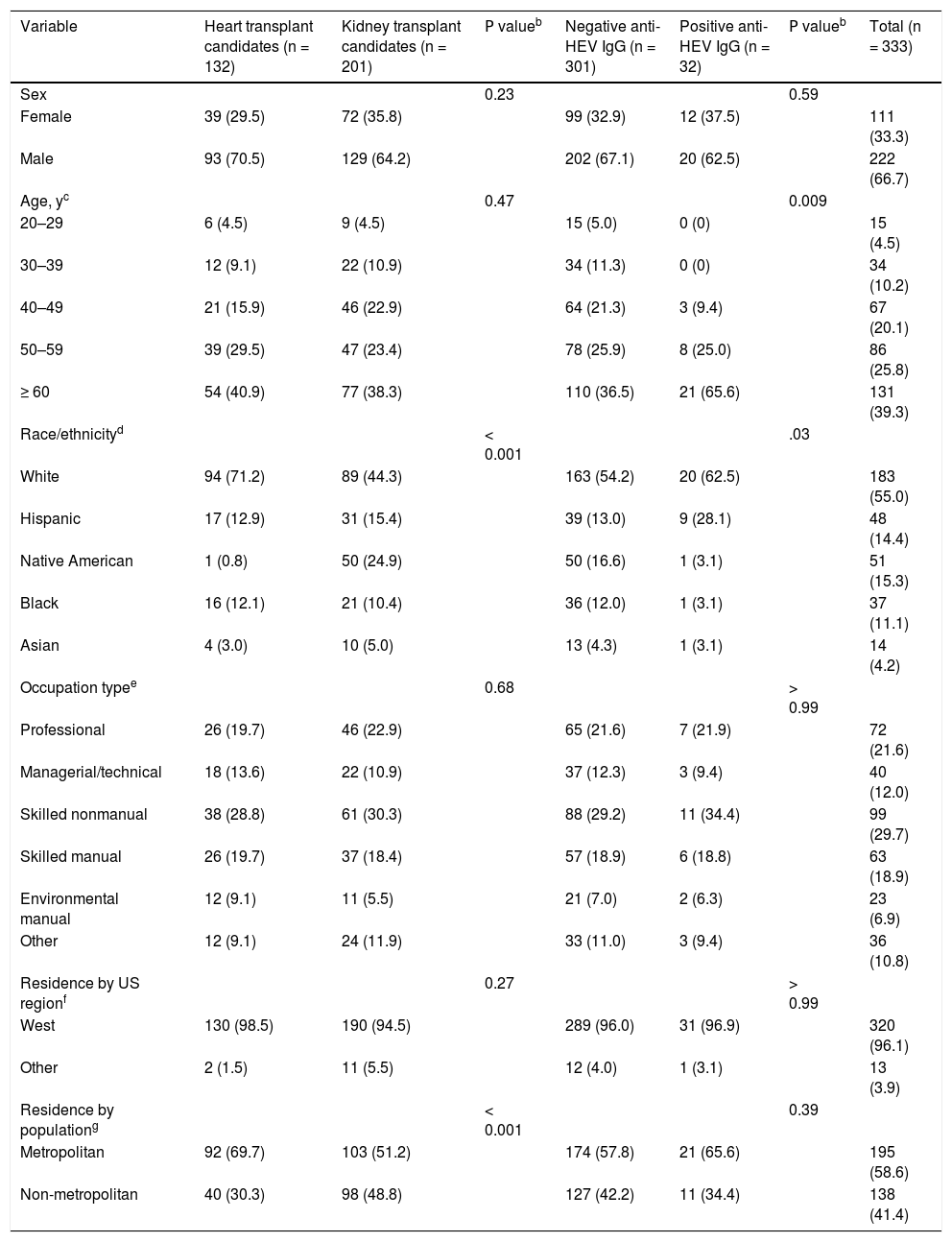

Demographic characteristics of heart and kidney transplant candidates.a

| Variable | Heart transplant candidates (n = 132) | Kidney transplant candidates (n = 201) | Ρ valueb | Negative anti-HEV IgG (n = 301) | Positive anti-HEV IgG (n = 32) | Ρ valueb | Total (n = 333) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.23 | 0.59 | |||||

| Female | 39 (29.5) | 72 (35.8) | 99 (32.9) | 12 (37.5) | 111 (33.3) | ||

| Male | 93 (70.5) | 129 (64.2) | 202 (67.1) | 20 (62.5) | 222 (66.7) | ||

| Age, yc | 0.47 | 0.009 | |||||

| 20–29 | 6 (4.5) | 9 (4.5) | 15 (5.0) | 0 (0) | 15 (4.5) | ||

| 30–39 | 12 (9.1) | 22 (10.9) | 34 (11.3) | 0 (0) | 34 (10.2) | ||

| 40–49 | 21 (15.9) | 46 (22.9) | 64 (21.3) | 3 (9.4) | 67 (20.1) | ||

| 50–59 | 39 (29.5) | 47 (23.4) | 78 (25.9) | 8 (25.0) | 86 (25.8) | ||

| ≥ 60 | 54 (40.9) | 77 (38.3) | 110 (36.5) | 21 (65.6) | 131 (39.3) | ||

| Race/ethnicityd | < 0.001 | .03 | |||||

| White | 94 (71.2) | 89 (44.3) | 163 (54.2) | 20 (62.5) | 183 (55.0) | ||

| Hispanic | 17 (12.9) | 31 (15.4) | 39 (13.0) | 9 (28.1) | 48 (14.4) | ||

| Native American | 1 (0.8) | 50 (24.9) | 50 (16.6) | 1 (3.1) | 51 (15.3) | ||

| Black | 16 (12.1) | 21 (10.4) | 36 (12.0) | 1 (3.1) | 37 (11.1) | ||

| Asian | 4 (3.0) | 10 (5.0) | 13 (4.3) | 1 (3.1) | 14 (4.2) | ||

| Occupation typee | 0.68 | > 0.99 | |||||

| Professional | 26 (19.7) | 46 (22.9) | 65 (21.6) | 7 (21.9) | 72 (21.6) | ||

| Managerial/technical | 18 (13.6) | 22 (10.9) | 37 (12.3) | 3 (9.4) | 40 (12.0) | ||

| Skilled nonmanual | 38 (28.8) | 61 (30.3) | 88 (29.2) | 11 (34.4) | 99 (29.7) | ||

| Skilled manual | 26 (19.7) | 37 (18.4) | 57 (18.9) | 6 (18.8) | 63 (18.9) | ||

| Environmental manual | 12 (9.1) | 11 (5.5) | 21 (7.0) | 2 (6.3) | 23 (6.9) | ||

| Other | 12 (9.1) | 24 (11.9) | 33 (11.0) | 3 (9.4) | 36 (10.8) | ||

| Residence by US regionf | 0.27 | > 0.99 | |||||

| West | 130 (98.5) | 190 (94.5) | 289 (96.0) | 31 (96.9) | 320 (96.1) | ||

| Other | 2 (1.5) | 11 (5.5) | 12 (4.0) | 1 (3.1) | 13 (3.9) | ||

| Residence by populationg | < 0.001 | 0.39 | |||||

| Metropolitan | 92 (69.7) | 103 (51.2) | 174 (57.8) | 21 (65.6) | 195 (58.6) | ||

| Non-metropolitan | 40 (30.3) | 98 (48.8) | 127 (42.2) | 11 (34.4) | 138 (41.4) |

Anti-HEV IgG: anti-HEV immunoglobulin G antibody.

Age category percentages for heart transplant candidates (n = 132) and for all transplant candidates (n = 333) total < 100% due to rounding.

Race/ethnicity category percentages for negative anti-HEV IgG transplant candidates (n = 301) total > 100% due to rounding; and race/ethnicity category percentages for positive anti-HEV IgG transplant candidates (n = 32) total < 100% due to rounding.

Occupation type category percentages for all transplant candidates (n = 333) total < 100% due to rounding.

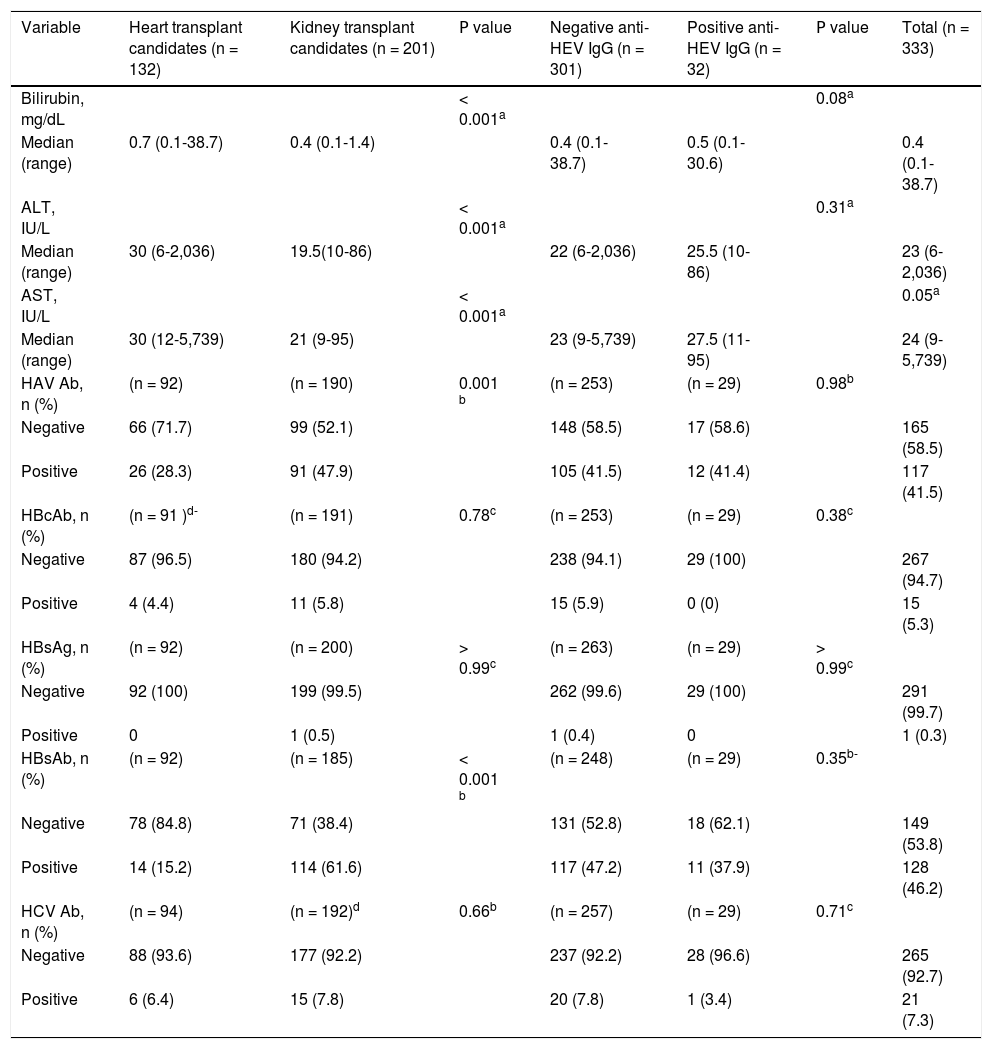

Laboratory characteristics of heart and kidney transplantation candidates.

| Variable | Heart transplant candidates (n = 132) | Kidney transplant candidates (n = 201) | Ρ value | Negative anti-HEV IgG (n = 301) | Positive anti-HEV IgG (n = 32) | Ρ value | Total (n = 333) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilirubin, mg/dL | < 0.001a | 0.08a | |||||

| Median (range) | 0.7 (0.1-38.7) | 0.4 (0.1-1.4) | 0.4 (0.1-38.7) | 0.5 (0.1-30.6) | 0.4 (0.1-38.7) | ||

| ALT, IU/L | < 0.001a | 0.31a | |||||

| Median (range) | 30 (6-2,036) | 19.5(10-86) | 22 (6-2,036) | 25.5 (10-86) | 23 (6-2,036) | ||

| AST, IU/L | < 0.001a | 0.05a | |||||

| Median (range) | 30 (12-5,739) | 21 (9-95) | 23 (9-5,739) | 27.5 (11-95) | 24 (9-5,739) | ||

| HAV Ab, n (%) | (n = 92) | (n = 190) | 0.001 b | (n = 253) | (n = 29) | 0.98b | |

| Negative | 66 (71.7) | 99 (52.1) | 148 (58.5) | 17 (58.6) | 165 (58.5) | ||

| Positive | 26 (28.3) | 91 (47.9) | 105 (41.5) | 12 (41.4) | 117 (41.5) | ||

| HBcAb, n (%) | (n = 91 )d- | (n = 191) | 0.78c | (n = 253) | (n = 29) | 0.38c | |

| Negative | 87 (96.5) | 180 (94.2) | 238 (94.1) | 29 (100) | 267 (94.7) | ||

| Positive | 4 (4.4) | 11 (5.8) | 15 (5.9) | 0 (0) | 15 (5.3) | ||

| HBsAg, n (%) | (n = 92) | (n = 200) | > 0.99c | (n = 263) | (n = 29) | > 0.99c | |

| Negative | 92 (100) | 199 (99.5) | 262 (99.6) | 29 (100) | 291 (99.7) | ||

| Positive | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | ||

| HBsAb, n (%) | (n = 92) | (n = 185) | < 0.001 b | (n = 248) | (n = 29) | 0.35b- | |

| Negative | 78 (84.8) | 71 (38.4) | 131 (52.8) | 18 (62.1) | 149 (53.8) | ||

| Positive | 14 (15.2) | 114 (61.6) | 117 (47.2) | 11 (37.9) | 128 (46.2) | ||

| HCV Ab, n (%) | (n = 94) | (n = 192)d | 0.66b | (n = 257) | (n = 29) | 0.71c | |

| Negative | 88 (93.6) | 177 (92.2) | 237 (92.2) | 28 (96.6) | 265 (92.7) | ||

| Positive | 6 (6.4) | 15 (7.8) | 20 (7.8) | 1 (3.4) | 21 (7.3) |

ALT: alanine aminotransferase. anti-HEV IgG: hepatitis Ε virus immunoglobulin G antibody. AST: aspartate aminotransferase. HAV Ab: hepatitis A virus antibody. HBcAb: hepatitis Β core antibody. HBsAb: hepatitis Β surface antibody. HBsAg: hepatitis Β surface antigen. HCV Ab: hepatitis C virus antibody.

The prevalence for HEV IgG antibodies was 11.4% (15/ 132) for heart transplant candidates and 8.5 % (17/201) for kidney transplant candidates, with an overall seroprevalence of 9.6% (32/333). None of the 333 patients tested positive for HEV RNA in the serum.

To evaluate possible risk factors associated with HEV infection, we compared the characteristics of patients with positive results for HEV IgG antibodies to those of patients with negative results for HEV IgG antibodies. We also compared heart vs. kidney transplant groups and found statistically significant differences associated with age, race/ethnicity, population in geographic area of residence, total bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), hepatitis A virus (HAV) antibodies, and hepatitis B surface antibodies (HBsAb) (Tables 1 and 2; Figure 1).

Heart transplant candidates were more frequently white (P < 0.001) and had higher total bilirubin, ALT, and AST levels (all P < 0.001) than kidney transplant candidates. Compared to heart transplant candidates, kidney transplant candidates had a higher percentage of positive HAV antibodies (47.9 vs. 28.3%; P = 0.001) and HBsAb (61.6 vs. 15.2%; P < 0.001).

In the univariate analysis, older age > 60 years, white race, bilirubin, ALT, AST, HAV antibodies, and HBsAb were all statistically associated with anti-HEV IgG antibodies. In the multivariable analysis, only age > 60 years had statistical significance. We evaluated possible associations with race, occupation, residence population, and US residence region because these variables have been associated with HEV IgG antibodies in the general US population8 but only white race was statistically significant in the univariate analysis.

DiscussionThe pre-transplant HEV seroprevalence (9.6%) was higher for heart candidates (11.4%) than for kidney candidates (8.5%), with no evidence of acute infection based on HEV RNA test results.

Previously, a few studies have evaluated pretransplant seroprevalence of HEV infection.6,10 A French study found HEV seroprevalence of 14.1% (99/700) in a group of kidney (14.5% [77/529]) and liver (12.9% [22/171]) transplant candidates.10 A German study found a prevalence of 1.5% (4/ 274) in heart transplant candidates and a prevalence of 7.3% (10/137) in nontransplanted cardiac patients.6 Acute HEV reactivation was not confirmed in SOT in a study that evaluated patients with positive HEV IgG antibodies but negative HEV RNA at transplant and at 1-year follow-up.10,12

Studies of seroprevalence of HEV infection in developed countries have variable results, most likely because of differences in the prevalence and incidence of HEV infection within and among different countries.11 Another possible explanation for these differences is the use of assays with poor sensitivity for detecting IgG and IgM HEV antibodies, resulting in underestimation of seroprevalence.9,12,13

In our study, we used a commercially available ELISA test for detection of HEV IgG antibodies (recomWell; Mikrogen, Neuried, Germany) that has a good analytical sensitivity compared with other assays.14 Currently, there are no US Food and Drug Administration-approved serologic assays in the US, which may have limited the diagnosis of HEV infection. Until recently, molecular assays were not standardized and had substantially varied performance among laboratories. WHO developed an international standard strain (code number 6329/10) using a genotype 3a HEV strain to improve interlaboratory results for detection and quantification of HEV RNA.15

The higher prevalence of HEV IgG antibodies found in heart transplant candidates is consistent with that reported from a previous study that evaluated heart transplant recipients.6 A possible explanation for this finding could be the higher exposure to blood products in patients with advanced cardiac disease.

All patients who had significantly elevated bilirubin were heart transplant candidates, and this finding could be secondary to their more severe disease compared to kidney transplant patients.

We found that kidney transplant candidates compared with heart transplant candidates had a higher prevalence of antibodies for HAV (47.9 vs. 28.3%, p = 0.001) and anti-HBs (61.6 vs. 12.2%, p < 0.001) this could represent a higher rate of vaccination in this population since a significant number of kidney transplant candidates are usually on hemodialysis and could have been screened more extensively for HAV and HBV than heart transplant candidates.

In our study previous exposure to HBV infection with positive HBcAb was similar in heart and kidney candidates (4.4 vs. 5.8%) and only one kidney transplant candidate had a positive HBsAg. Current guidelines recommend vaccination for HAV in heart and kidney candidates and recipients that have increase risk of exposure. Solid organ transplant candidates that have a negative HB-sAb should receive vaccination for HBV since the risk increases due to long-term immunosuppression.16 In heart transplant patients it has been reported that up to 20% of patients acquired hepatitis B after transplantation.17 Regarding HCV antibodies, the prevalence was similar in heart and kidney transplant candidates (6.4 vs. 7.8%). The seroprevalence of HCV infection in patients that are on hemodialysis has been estimated as 13.5% compared with 3% in the general population18 and is even higher after kidney transplantation (11 to 49%).19 In heart transplant recipients the prevalence of HCV has been reported from 7 to 18%.20

Our study had several limitations, and our results should be interpreted in the context of the study design. Considering that in the US, the incidence rate of HEV infection has been calculated as 7/1,000 persons per year using a model that estimates incidence based on seroprevalence data from NHANES III,21 our sample size is small for detecting new cases of HEV infection. We did not assess HEV markers after transplantation and the probability of detecting HEV RNA in a small number of non-immunosuppressed candidates for SOT is quite low and does not predict the outcome or the possible complications after transplantation. In the context of acute HEV infection, the period of viremia may be brief, and negative HEV RNA does not exclude the diagnosis, in that case, testing serum for anti-HEV IgM antibodies would have been more accurate to detect patients with acute HEV and HEV RNA below the level of detection. We used a molecular assay to detect HEV RNA that has not yet been validated, although preliminary testing has shown it to have a specificity of 99.95% (95% CI, 99.88–99.98%).

We consider that routine screening for HEV infection in the pretransplant solid organ population requires further investigation. The possible role of HEV antibodies as protective for HEV infection or if they are a marker of risk for infection in the post transplant population needs additional investigation. We conclude that the prevalence of HEV IgG antibodies was higher in heart than in kidney transplant candidates and that there was no evidence of active infection (HEV RNA) in any of the patients. The only variable associated with HEV-positive IgG was age > 60 years.

Abbreviations- •

ALT: alanine aminotransferase.

- •

anti-HEV IgG: hepatitis E virus IgG antibody.

- •

AST: aspartate aminotransferase.

- •

ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

- •

HAV: hepatitis A virus.

- •

HB: hepatitis B.

- •

HBsAb: hepatitis B surface antibody.

- •

HEV: hepatitis E virus.

- •

IgG: immunoglobulin G.

- •

IgM: immunoglobulin M.

- •

NHANES: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

- •

OR: odds ratio.

- •

SOT: solid-organ transplant.

- •

WHO: World Health Organization.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Part of this study was presented at the 2014 World Transplant Congress, San Francisco, California, July 30, 2014 as a poster presentation.

Authors ContributionsConcept/design: Dr. Unzueta, Dr. Valdez, Dr. Rakela.

Data analysis/statistics: Dr. Chang.

Drafting article: Dr. Unzueta.

Critical revision of article: Dr. Rakela, Dr. Heilman, Dr. Scott, Dr. Douglas.

Data collection: Dr. Valdez, Ms. Desmarteau.