Hepatic hydrothorax (HH) is a pleural effusion that develops in a patient with cirrhosis and portal hypertension in the absence of cardiopulmonary disease. Although the development of HH remains incompletely understood, the most acceptable explanation is that the pleural effusion is a result of a direct passage of ascitic fluid into the pleural cavity through a defect in the diaphragm due to the raised abdominal pressure and the negative pressure within the pleural space. Patients with HH can be asymptomatic or present with pulmonary symptoms such as shortness of breath, cough, hypoxemia, or respiratory failure associated with large pleural effusions. The diagnosis is established clinically by finding a serous transudate after exclusion of cardiopulmonary disease and is confirmed by radionuclide imaging demonstrating communication between the peritoneal and pleural spaces when necessary. Spontaneous bacterial empyema is serious complication of HH, which manifest by increased pleural fluid neutrophils or a positive bacterial culture and will require antibiotic therapy. The mainstay of therapy of HH is sodium restriction and administration of diuretics. When medical therapy fails, the only definitive treatment is liver transplantation. Therapeutic thoracentesis, indwelling tunneled pleural catheters, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt and thoracoscopic repair of diaphragmatic defects with pleural sclerosis can provide symptomatic relief, but the morbidity and mortality is high in these extremely ill patients.

Hepatic hydrothorax (HH) is defined as a pleural effusion, typically more than 500 mL, in patients with liver cirrhosis without coexisting underlying cardiac or pulmonary disease.1,2 It is an infrequent complication of portal hypertension with an estimated prevalence of 5-10% among cirrhotic patients.2–4 Although pleural effusion in association with liver disease was first described in the nineteenth century by Laënnec, HH was first defined by Morrow, et al.5 in 1958 while describing a rapid accumulation of massive right pleural effusion after the diagnosis of cirrhosis. Together with hepatopulmonary syndrome and pulmonary hypertension, HH have been recognized as a major pulmonary manifestation of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis in recent years.1,6 In most cases, HH develops on the right side (85%), with 13% of cases occurring on the left side and 2% bilateral.2,3,7 A recent study showed that the frequency of HH was associated with hepatic function as assessed by Child Pugh scoring system, but not with serum albumin.8 Although it is commonly seen in conjunction with ascites, HH can present in the absence of ascites in a small proportion of patients.9 In contrast with ascites where a significant volume (5 to 8 L) are generally well-tolerated without signicant symptom, a patient with HH will develop dyspnea, shortness of breath, and/or hypoxia when only 1 to 2 L of fluid accumulates in the pleural space.7,10,11

In this clinical review, the pathophysiology, manifestations, diagnosis, and therapeutic options available for the management of HH will be discussed in order to allow the clinician to better understand these potentially life-threatening complications.

PathophysiologyAlthough the exact mechanisms involved in the development of hepatic hydrothorax have not been well-defined, several mechanisms have been postulated, including hypoalbuminemia and subsequently decreased colloid osmotic pressure, increased azygos system pressure leading to leakage of plasma into the pleural cavity and transdiaphragmatic migration of peritoneal fluid into the pleural space via lymphatic channels.12–14 However, the most widely accepted theory is the direct passage of ascitic fluid from peritoneal to the pleural cavity via numerous diaphragmatic defects.15–17

These defects, which are referred to as pleuroperitoneal communications, are usually < 1 cm and tend to occur on the right side.15,17,18 This right side predominance could be related to the embryological development of the diaphragm in which the left side of the diaphragm is more muscular and the right side is more tendinous due to the close anatomical relationship with bare areas of the liver.19 On the microscopic examination, these defects were revealed as discontinuities in the collagen bundles that make up the tendinous portion of the diaphragm.17 Macroscopically, the diaphragmatic defects associated with the development of HH have been classified into four morphological types: Type 1, no obvious defect; type 2, blebs lying in the diaphragm; type 3, broken defects (fenestrations) in the diaphragm; and type 4, multiple gaps in the diaphragm.18

Although diaphragmatic defects occur in the normal population and autopsy series report such defects in up to 20% of cases, they seem to rarely result in pneumothorax following laparoscopic procedures.18,20 In patients with ascites, the increasing abdominal pressure and the diaphragmatic thinning secondary to malnutrition of cirrhotic patients enlarge these defects.1,13,21 Blebs of herniated peritoneum can protrude through these defects, and, if a bleb bursts, a communication between peritoneal and pleural space is formed.18,22,23 The movement of fluid from the abdomen to the pleural space is unidirectional, which is probably due to a permanent gradient pressure as a result of a negative intrathoracic pressure during the respiratory cycle and a positive intra-abdominal pressure.24 If the volume of accumulation of ascites in the pleural cavity exceeds the absorptive capacity of the pleural membranes, hepatic hydrothorax ensues.

This mechanism has been confirmed by imaging technique demonstrating the communication between the peritoneal cavity and the pleural space even in the absence of ascites.25–30 Several available methods to evaluate pleural migration include intraperitoneal injection of blue dye or air,24 contrast-enhanced ultrasonography29–31 and scintigraphic studies using intraperitoneal instillation of 99mTchuman serum albumin or 99mTc-sulphor-colloid.16,26,32,33 On the other hand, other theories in that the underlying mechanisms leading to fluid retention in patients with HH are similar to those leading to other forms of fluid accumulation in patients with cirrhosis have failed to explain the right predominance of HH.10,12,13,34

Clinical ManifestationsAs HH most frequently occurs in the context of ascites and other features of portal hypertension due to decompensated liver disease, the prominent clinical manifestations are nonspecific and related to cirrhosis and ascites in most cases.7,9,35,36 More rarely, HH may be the index presentation for chronic liver disease.9 The respiratory symptoms in patients with HH varied, mainly depending on the volume of effusion, rapidity of the effusion accumulation in the pleural space and the presence of associated cardiopulmonary disease.1,7,12 Patients may be asymptomatic in whom pleural effusion is an incidental finding on chest imaging performed for other reasons or they may have pulmonary symptoms of shortness of breath, cough, hypoxemia or respiratory failure associated with large pleural effusions.10,13,21,37 A recent case series including 77 patients with HH indicated that most patients typically had multiple complaints, with the most commonly reported symptoms being dyspnea at rest (34%), cough (22%), nausea (11%), and pleuritic chest pain.7 On rare occasions, patients with HH may present with an acute tension hydrothorax, manifesting as severe dyspnoea and hypotension.7

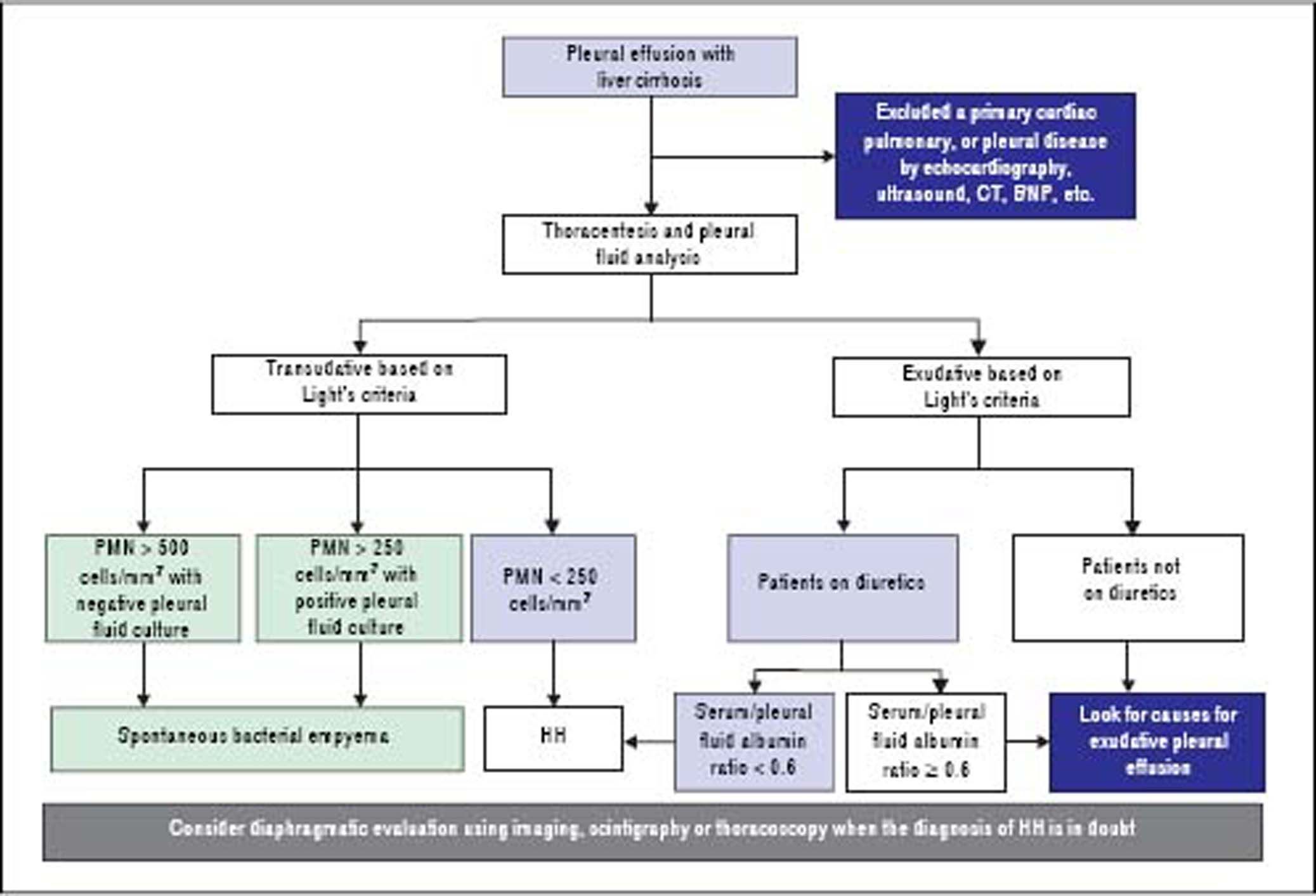

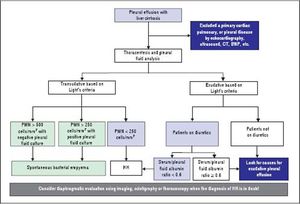

DiagnosisThe diagnosis of HH is based on the presence of hepatic cirrhosis with portal hypertension; exclusion of a primary cardiac, pulmonary, or pleural disease; and eventually, confirmation of the passage of ascites into pleural space (Figure 1).2,33,38

Pleural fluid analysis is mandatory to identify the nature of the fluid, to exclude the presence of infection including spontaneous bacterial empyema (SBEM), and to rule out alternative diagnosis (inflammation or malignancy).39 One retrospective series40 found that 70% of pleural effusions in a cohort of 60 cirrhotic patients admitted with pleural effusions who underwent diagnostic thoracentesis were due to uncomplicated HH, 15% were due to infected HH, and 15% were due to causes other than liver disease including SBEM, pleural tuberculosis, adenocarcinoma, parapneumonic effusions, and undiagnosed exudates. In addition, 80% of right-sided pleural effusions were found to be uncomplicated HH, while only 35% of left-sided pleural effusions were uncomplicated HH.

Pleural fluid analysis should routinely include serum and fluid protein, albumin and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, cell count, Gram stain and culture in blood culture bottles.2,37,41 Other tests that may be useful depending on clinical suspicion, include triglycerides, pH, adenosine deaminase and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for mycobacteria, amylase, and cytology to exclude chylothorax, empyema, tuberculosis, pancreatitis, and malignancy, respectively.4,10,36,37,42 The composition of HH is transudative in nature and therefore similar to the ascetic fluid.42–44 However, total protein and albumin may be slightly higher in HH compared with levels in the ascitic fluid because of the greater efficacy of water absorption by the pleural surface.12,34,39,40,44,45

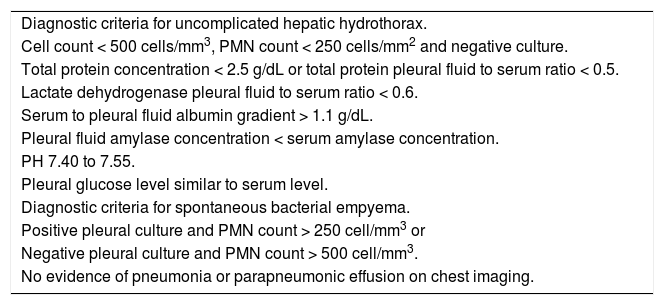

In uncomplicated HH, total protein is < 2.5 g/dL in HH with low LDH and glucose levels similar to that in serum.12,42 In addition, it will also have a serum to pleural fluid albumin gradient > 1.1 as found in ascites secondary to portal hypertension, although this has not been studied extensively (Table 1).12,42 Although diuresis has widely been reported to increase the pleural total protein levels, one study found only a single patient had a protein discordant exudate despite 34 patients receiving diuretics.39 However, when HH is an exudate probably because of diuretics, the serum/pleural fluid albumin ratio should be calculated, and a value <0.6 is classified as transudate.43,44

Diagnostic criteria for hepatic hydrothorax.

| Diagnostic criteria for uncomplicated hepatic hydrothorax. |

| Cell count < 500 cells/mm3, PMN count < 250 cells/mm2 and negative culture. |

| Total protein concentration < 2.5 g/dL or total protein pleural fluid to serum ratio < 0.5. |

| Lactate dehydrogenase pleural fluid to serum ratio < 0.6. |

| Serum to pleural fluid albumin gradient > 1.1 g/dL. |

| Pleural fluid amylase concentration < serum amylase concentration. |

| PH 7.40 to 7.55. |

| Pleural glucose level similar to serum level. |

| Diagnostic criteria for spontaneous bacterial empyema. |

| Positive pleural culture and PMN count > 250 cell/mm3 or |

| Negative pleural culture and PMN count > 500 cell/mm3. |

| No evidence of pneumonia or parapneumonic effusion on chest imaging. |

Adapted from reference 1. PMN: polymorphonuclear.

To exclude a primary cardiac, pulmonary, or pleural disease, a chest radiograph should be performed in addition to pertinent laboratory tests, such as a brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) in the proper clinical setting.39,46,47 In patients with massive pleural effusion, the radiograph should be repeated when the effusion has decreased considerably (after diuresis or therapeutic thoracentesis) to evaluate pulmonary or pleural pathology that was masked by the effusion.39 A computed tomographic (CT) scan of the chest will help to exclude mediastinal, pulmonary, or pleural lesions or malignancies.7,42,48 Echocardiography should be performed to evaluate cardiac function and to rule any cardiac causes of pleural effusions.49,50 In a study of 41 HH patients, diastolic dysfunction was found in 11 of 21 patients (52%). Contrast echocardiography with agitated saline demonstrated an intrapulmonary shunt in 18 of 23 cases (78%).39 However, the study did not mention how these patients were distinguished from left heart failure. The high prevalence of diastolic dysfunction suggest that heart failure might have contributed to the development of pleural effusions.6,39,49,50 The increased neurohormonal activity associated with cirrhosis leading to cardiac hypertrophy along with impaired relaxation has been speculated as the reason for diastolic dysfunction in cirrhotic patients.10,39 Traditionally, the simplest strategy to reveal the true transudative nature of heart failure-related effusions, labeled as exudates by Light’s criteria, is to calculate the serum to pleural fluid albumin gradient.44 A recent study demonstrated that a gradient between the albumin levels in the serum and the pleural fluid > 1.2 g/dL performs significantly better than a protein gradient > 3.1 g/dL to correctly categorize mislabeled cardiac effusions. On the other hand, the accuracy of a pleural fluid to serum albumin ratio < 0.6 excelled when compared with albumin and protein gradients in patients with miscategorized HH.43,44

Diaphragmatic evaluationIn cases where the diagnosis of HH is in doubt, in particular when pleural effusion is left sided and/or ascites are absent, diagnosis of HH can be confirmed when a communication is identified between the peritoneal and thoracic cavities.10,13,34,38 Scintigraphic studies using intraperitoneal instillation of 99mTc-human serum albumin or 99mTc-sulphor-colloid, is used most frequently because it is simple and safe.24 These radiolabeled particles, measuring between 3 and 100 µm, are not absorbed by the peritoneum so their intrapleural passage occurs only through an anatomical defect in the diaphragm.24,51 It has been demonstrated that radiotracers are effective in demonstrating peritoneopleural communication even in the absence of ascites.26,27,52 This technique has sensitivity and specificity rates of 71% and 100%, respectively.52 In cases with minimal ascites, it has been recommended that intraperitoneal instillation of 300-500 mL of normal saline to favor the pleural passage of radioactivity is helpful to improve the effectiveness of peritoneal scintigraphy in the diagnosis of HH.24 The scintigraphic studies can also provide an estimation of the size of the diaphragmatic defect(s) by the rapidity with which the radioisotope passes from the peritoneum to the pleural space.33 In addition, intraperitoneal injection of methylene blue can be used intraoperatively to demonstrate and localize defects, and contrast-enhanced ultrasonography has been used to detect flow across the diaphragm in real time.29–31 Although other diagnostic modalities, including magnetic resonance imaging and CT could also be used to detect the underlying diaphragmatic defects,15,48 direct demonstration of defects with those techniques might be extremely difficult, as the defect itself is usually quite small.39 Video-assisted thoracoscopy, which can provide a directly visualization of the underlying diaphragmatic defects,18,20 is an alternative diagnostic option. However, this modality is invasive and should be considered only when diagnosis is not clear or in case there is a plan to repair the diaphragmatic defects.34

Spontaneous bacterial empyemaSpontaneous bacterial empyema (SBEM) is an infection of a preexisting hydrothorax in the absence of pneumonia.53,54 It is reported to occur in 2.0% to 2.4% of patients with cirrhosis and 13% to 16% of patients with HH.55–57 The actual incidence of SBEM may be higher than reported because of underdiagnosis.58–60 The initiation of empirical antibiotics in patients with cirrhosis and fever or hepatic encephalopathy because of a higher suspicion for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis masks the diagnosis of SBEM.58–60 SBEM should be distinguished from empyema secondary to pneumonia, because there is usually no evidence of pus or abscess in the thoracic cavity in SBEM and it differ in the pathogenesis, clinical course, and treatment strategy with those of empyema secondary to pneumonia.61–63 Therefore, some authors have proposed that it be called spontaneous bacterial pleuritis.1,10,12,34

Even-though the exact mechanism of SBEP remains unclear, it is believed that the pathogenesis is similar to spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) in that transient bacteremia leads to infection of the pleural fluid due to impaired reticuloendothelial phagocytic activity.3,53,54,56,61–64 In up to 40% of cases, SBEM can occur in the absence of SBP and even in the absence of ascites, indicating that SBP is not prerequisite for SBEM.3,53,55–57 The risk factors identified for the development of SBEM in patients with cirrhosis include: low pleural fluid C3 levels, low serum albumin pleural fluid total protein, high Child-Pugh score and concomitant SBP.3,55,56,65 Similar to SBP, the more frequent bacteria involved in SBEP are E. coli, Klebsiella, Streptococcus and Enterococcus species.3,55–57, 66,67

The presenting symptoms of SBEM may be those of accompanying SBP (i.e., abdominal pain), may be limited to the thoracic cavity (i.e., dyspnea, thoracic pain), or may be systemic in nature (i.e., fever, shock, new or worsening encephalopathy).54,68 Given the high mortality rate, a high index of suspicion is essential for the diagnosis of SBEM in cirrhotic patients who develop fever, pleuritic pain, encephalopathy, or unexplained deterioration in renal function.3,54,66,68

The diagnostic criteria for spontaneous bacterial empyema are similar to those for SBP, requiring a polymorphonuclear (PMN) cell count > 250 cells/mm3 with a positive culture or PMN cell count > 500 cells/mm3 in cases with negative cultures; no evidence of pneumonia and/or contiguous infections process; and a serum/pleural fluid albumin gradient > 1.1 (Table 1).56,65 As with ascites fluid cultures, pleural fluid should be inoculated immediately into blood culture bottles at the bedside to increase the microbiologic yields.55,56 Bedside inoculation resulted in positive cultures in 75% of the episodes. The positivity was only 33% when conventional microbiological techniques were used.55,56 Detection of pleural neutrophilia provides an early diagnosis of SBEM when culture results are delayed.54,66

Initial adequate antimicrobial therapy is the cornerstone of the treatment. Given the association with SBP, the initial antibiotic regimen is similar and the recommended treatment is an intravenous third-generation cephalosporin given for 7 to 10 days.12,54,58,61 Considering its proven benefit in SBP, some centers administer albumin similarly in patients with SBEM, although the use of albumin has not been specifically studied in SBEM.3,68 Placement of a chest tube is generally not recommended in SBEM even in culture-positive cases, because it can lead to life-threatening fluid depletion, protein loss, and electrolyte imbalance.21,69–71 The only indication for chesttube drainage for SBEM is pus in the pleural space. Due to the impaired liver function, frequently with associated renal insufficiency in most cirrhotic patients with SBEM, the management of SBEM is a clinical challenge.54 Despite aggressive therapy, the mortality is high (up to 20%) in these fragile patients.54,56 The independent factors related to poor outcome are high models for end-stage liver disease (MELD)-Na score, initial ICU admission and initial antibiotic treatment failure.68

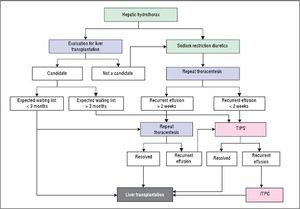

ManagementMedical managementBecause the overwhelming mechanism is transdiaphragmatic ascites flow, the principal treatment should focus on eliminating and preventing the recurrence of ascites. A sodium-restricted diet and judicious use of diuretics through inducing and maintaining a net negative sodium balance may provide initial ascites reduction and prevent HH development.72,73 A low sodium diet, with 70-90 mmol per day, and weight loss of 0.5 kg per day in patients without edema, and 1.0 kg per day in those with edema is the goal of therapy.64 Dietary education should be given to patients at the same time. However, diet therapy is usually not sufficient to achieve such a goal. Therefore, diuretics are required in the vast majority of cases. A distal acting agent (typically spironolactone 100 mg/day) and a loop diuretic (e.g. furosemide 40 mg/day) should be co-administered as the best initial regimen to produce a renal excretion of sodium at least 120 mEq per day.11,74 The doses may be increased in a stepwise fashion every 3-5 days by doubling the doses with furosemide up to 160 mg/day and spironolactone up to 400 mg/day.37,38 Urinary sodium should be checked before and during therapy to adjust diuretic dosage as per clinical response.2,13

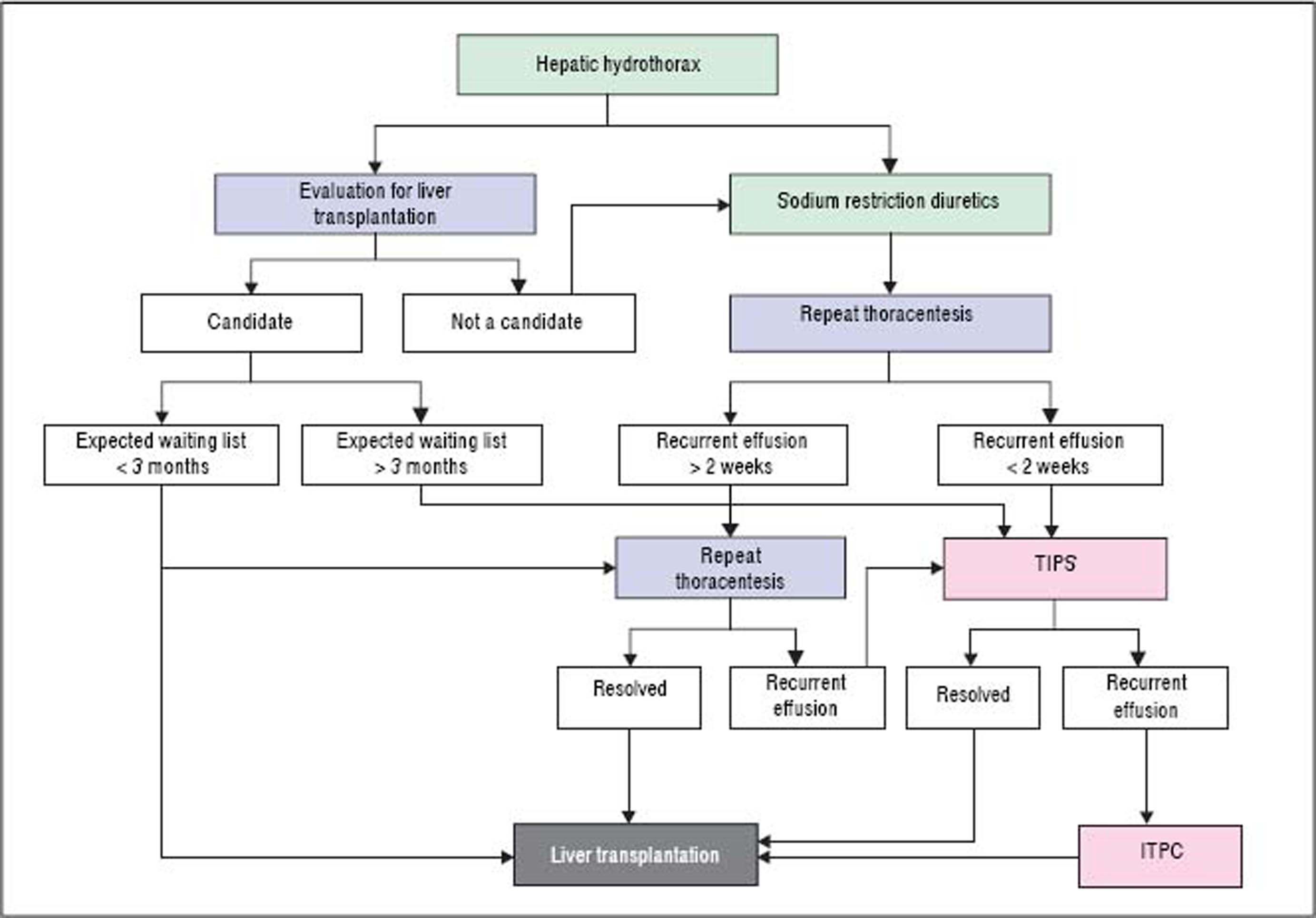

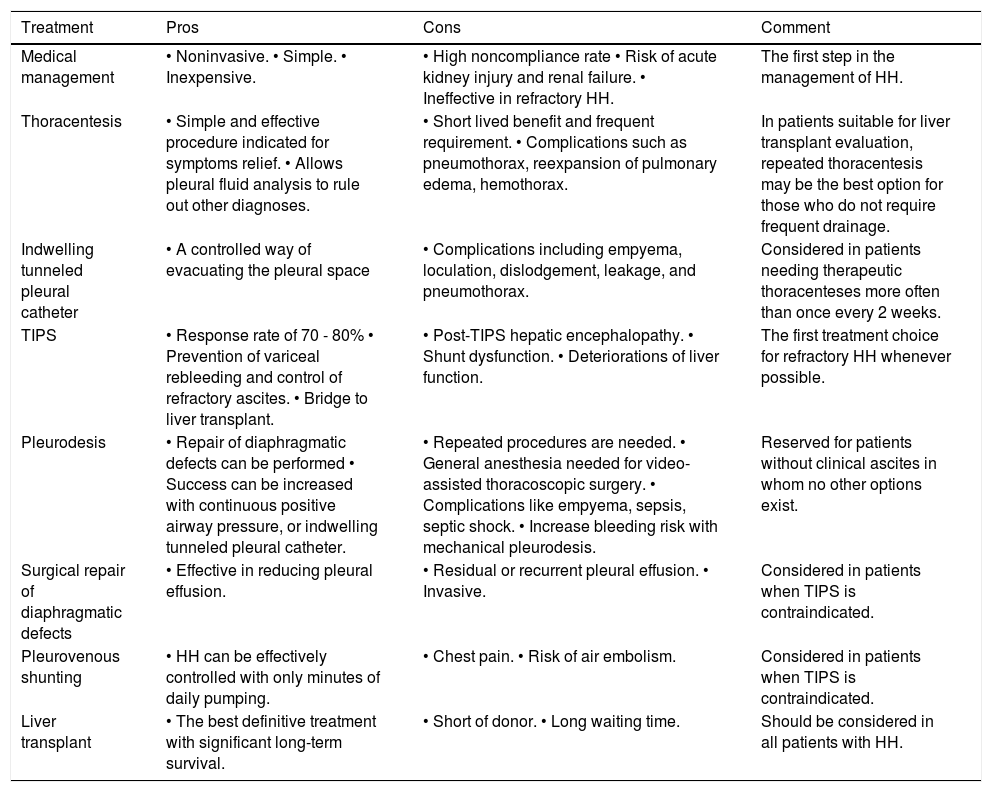

Refractory hepatic hydrothoraxDespite medical therapy with diuretics and sodium restriction, many patients still experience intractable dyspnea and respiratory compromise due to persistent hydrothorax. Moreover, in many patients, diuretic-induced electrolyte imbalances, renal abnormalities, or precipitation of encephalopathy may preclude successful symptomatic control of the pleural effusion. These patients are considered to have refractory hepatic hydrothorax.2,12,34 Approximately 21% to 26% of medically treated patients may fall into this category.73,75 The only definitive treatment for refractory HH is liver transplantation.14,72 In patients awaiting liver transplantation and those who are not transplant candidates, the aims of therapy for refractory HH are relief of symptoms and prevention of pulmonary complications (Figure 2).1,10,34 The therapeutic options available are therapeutic thoracentesis, chest tube placement and indwelling pleural catheter, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), and surgical interventions (Table 2).72

Pros and cons of the different treatment modalities for hepatic hydrothorax.

| Treatment | Pros | Cons | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical management | • Noninvasive. • Simple. • Inexpensive. | • High noncompliance rate • Risk of acute kidney injury and renal failure. • Ineffective in refractory HH. | The first step in the management of HH. |

| Thoracentesis | • Simple and effective procedure indicated for symptoms relief. • Allows pleural fluid analysis to rule out other diagnoses. | • Short lived benefit and frequent requirement. • Complications such as pneumothorax, reexpansion of pulmonary edema, hemothorax. | In patients suitable for liver transplant evaluation, repeated thoracentesis may be the best option for those who do not require frequent drainage. |

| Indwelling tunneled pleural catheter | • A controlled way of evacuating the pleural space | • Complications including empyema, loculation, dislodgement, leakage, and pneumothorax. | Considered in patients needing therapeutic thoracenteses more often than once every 2 weeks. |

| TIPS | • Response rate of 70 - 80% • Prevention of variceal rebleeding and control of refractory ascites. • Bridge to liver transplant. | • Post-TIPS hepatic encephalopathy. • Shunt dysfunction. • Deteriorations of liver function. | The first treatment choice for refractory HH whenever possible. |

| Pleurodesis | • Repair of diaphragmatic defects can be performed • Success can be increased with continuous positive airway pressure, or indwelling tunneled pleural catheter. | • Repeated procedures are needed. • General anesthesia needed for video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. • Complications like empyema, sepsis, septic shock. • Increase bleeding risk with mechanical pleurodesis. | Reserved for patients without clinical ascites in whom no other options exist. |

| Surgical repair of diaphragmatic defects | • Effective in reducing pleural effusion. | • Residual or recurrent pleural effusion. • Invasive. | Considered in patients when TIPS is contraindicated. |

| Pleurovenous shunting | • HH can be effectively controlled with only minutes of daily pumping. | • Chest pain. • Risk of air embolism. | Considered in patients when TIPS is contraindicated. |

| Liver transplant | • The best definitive treatment with significant long-term survival. | • Short of donor. • Long waiting time. | Should be considered in all patients with HH. |

HH: Hepatic hydrothorax. TIPS: Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

Thoracentesis is a simple and effective procedure indicated for relief symptoms of dyspnea in patients with large effusions and those with recurrent or refractory hydrothorax, although the benefits of the procedure are often short lived, and the procedure usually need to be repeated.10,76 In general, it is recommended that no more than 2 L be removed because there is a risk of hypotension or re-expansion of pulmonary edema.40,77 Chest X-rays and CT scan of the chest before therapeutic thoracentesis help to define the size of the effusion. After the procedure, the chest radiograph is also advisable, not only for detection of pneumothorax but also to evaluate pulmonary or pleural pathology that was masked by the effusion.40,77 Coagulopathy of cirrhosis is not deemed as contraindication to therapeutic thoracenthesis unless there is disseminated intravascular coagulation.12,13,21,34,78 Thoracentesis for HH in clinical practice is usually safe. The risk of pneumothorax after serial thoracocentesis increases from 7.7% to 34.7%. Other possible complications include pain at puncture site, pneumothorax, empyema or soft tissues infection, haemoptysis, air embolism, vasovagal episodes, subcutaneous empysema, bleeding (haematoma, haemothorax, or haemoperitoneum), laceration of the liver or spleen.40,77

Chest tube placement and indwelling tunneled pleural catheterA chest tube should not be placed in this patient population as it may result in protein loss, secondary infection, pneumothorax, hemothorax and hepatorenal syndrome and electrolyte disturbances.70,71,79,80 It can also be difficult to remove the chest tube because there is often a rapid reaccumulation of fluid once the chest tube is clamped.70,79

Indwelling tunneled pleural catheter (ITPC, also known as PleurX or Denver catheter) was initially intended for palliative outpatient therapy of recurrent malignant pleural and ascitic effusions and now it has become a common therapeutic tool in the management of symptomatic malignant effusions.81–83 There are an increasing number of reports of its usage for benign pleural conditions, including HH.82,84–88 A recent meta-analysis by Patil, et al.89 regarding the use of IPTC for nonmalignant pleural effusions demonstrated a spontaneous pleurodesis rate of 51%. In a recent prospective study,81 25 ITPCs were placed in 24 patients. The mean number of pleural drainage procedures before ITPC placement was 1.9, with no further pleural drainages required in any patient after ITPC placement. Spontaneous pleurodesis occurred in 33% patients and pleural fluid infection occurred in 16.7% patients. Even though these results look promising, data are limited and further studies are required to compare the effectiveness with other treatment modalities.72,90,91

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shuntTransjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is a nonsurgical approach that decompresses the portal system, thereby addressing the mechanism of fluid collection in the abdomen and/or chest.75 In a carefully selected population, TIPS can lead to significant improvements in the complications related to portal hypertension.75,92–96 It is now the standard of care in patients with refractory HH. Moreover, TIPS is superior to other treatment modalities in the prevention of rebleeding from varices and its control of refractory ascites which has been well studied in controlled trials.75

The efficacy and safety of TIPS for HH has been investigated in several non-controlled studies and case reports.75,92–98 A recent meta-analysis including six studies of 198 patients showed that the complete response rate to TIPS was 55.8% (95%CI: 44.7%-66.9%), partial response rate was 17.6% (95%CI: 10.9%-24.2%).99 A recent case series reported that TIPS was effective in 73.3% of 19 cases.100 It should be noted that the stents used in most of these studies were bare metal stents and, as expected, the rate of shunt dysfunction leading to recurrent hydrothorax was high.99 With the use of PTFE-covered stents in this setting, the shunt patency has been improved greatly101–103 which will extend the benefit of TIPS for HH. The incidence of TIPS-related encephalopathy was 11.7% (95%CI: 6.3%-17.2%), most of which is controllable with medical therapy.104,105 Only 5% of cases require occlusion of TIPS or a reduction in the TIPS caliber to control encephalopathy.

However, TIPS does not improve the overall prognosis of patients with end-stage liver disease. The average 30-day mortality rate was 18% and the 1-year survival was 52%.92–94,106 Risk factors for mortality after TIPS placement for HH include a Child-Pugh score ≥ 10, MELD score > 15, and an elevated creatinine.92–94 In addition, a lack of response in the hydrothorax after TIPS placement is associated with an increased mortality rate.92–94 Because TIPS shunts blood away from the liver and reduces the effective portal perfusion to the liver, it can precipitate liver failure in patients with already significant hepatic dysfunction. Ideally, patients with a high likelihood of decompensation after TIPS should also initiate evaluation for liver transplantation, with TIPS serving only as a bridge.93,94,99

Surgical interventionsThree surgical approaches have been used in the management of HH, including chemical pleurodesis (via tube thoracostomy or VATS), repair of diaphragmatic defects or fenestrations with/without pleurodesis, and peritoneovenous shunts or pleurovenous shunting.10

PleurodesisPleurodesis is a technique that consists of the ablation of the space between the parietal and visceral pleura with a sclerosing agent or irritant (such as talc or a tetracycline) that is administered through a tube thoracostomy (chest tube) or by thoracoscopy (VATS).107–111 It is usually reserved for patients without clinical ascites in whom no other options exist.107,111–113 The reason for this recommendation is that successful pleurodesis requires visceral and parietal pleural apposition, which can be difficult to achieve in refractory HH patients due to rapid fluid accumulation.14 Paracentesis performed before pleurodesis may also increase the success rate by decreasing ascites and flux of fluid from the peritoneal to the pleural cavity, allowing more time for the pleural spaces to be opposed to each other.114 The ITPC may also be combined with pleurodesis to avoid and decrease hospitalization.115,116 In addition, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), by increasing positive intrathoracic pressure and reversing the peritoneal-pleural pressure gradient, in combination with pleurodesis was reported to improve the success rate in one study.117

A meta-analysis by Hou, et al.118 comprising 180 refractory HH patients who were subjected to pleurodesis in 13 studies demonstrated an initial mean success rate of 72% with a further symptomatic recurrence in 25% of the cases. The rate off complete response to pleurodesis by chest tube was 78% (95% CI 68-87%), while using a video thoracoscopic (VATS) approach combined with talc poudrage pleurodesis, the rate of complete response rate was up to 84% (95% CI 64-97%).118 According to the drugs used for pleurodesis, complete response to pleurodesis with talc alone was 71% (95% CI 63-79%), and the complete response rate with OK-432 alone or in combination with minocycline was 93% (95% CI 78-100%).118

Various complications frequently observed after pleurodesis include fever and mild thoracic pain, though empyema, pneumothorax, pneumonia, septic shock and hepatic encephalopathy with liver failure have also been reported.107,111–113,118 Persistent high volume ascitic drainage from the chest tube site causing azotemia and renal failure is another dreaded complication when the chest tube is left for a prolonged period. Mechanical pleurodesis carries a high risk of bleeding especially in patients with advanced liver disease and coagulopathy.109

Surgical repair of diaphragm defectsDue to the proposed diaphragmatic defects HH mechanism, surgical approaches focused on defects repair with fibrin glue or sutures have been reported.119 Although closure of transdiaphragmatic defects can be done by open thoracotomy and by VATS with concomitant talc pleurodesis, open thoracotomy in a cirrhotic patient has a significant mortality.119

In a small series of eight patients who underwent VATS for refractory HH, demonstrable diaphragmatic defects were founded in six (75%) patients. The pleural effusion did not recur in the six patients with defects that were closed, but the other two patients had recurrent effusion and died 1 and 2 months following the procedure, respectively.120 In another series reported by Milanez de Campos, et al.121 in which 21 thoracoscopies were performed in 18 patients with HH, the overall success rate was 48%. Of those five patients in whom a suture could be performed, three had a good response (60%), one died of postoperative pneumonia and liver failure, and the other had empyema and drained fluid for 1 month. Ten of the 21 (47.6%) procedures had a good response. However, the high morbidity (57.1%) and mortality (38.9%) in this study during a follow-up period of 3 months raised questions about the utility of such an approach.

Although VATS for suturing diaphragmatic defects is effective in reducing pleural effusion in patients with HH, residual or recurrent pleural effusion has been observed clinically.122,123 To resolve this problem, the use of thoracoscopic mesh onlay reinforcement to prevent ascites leaking from sutured holes in patients with refractory HH has been introduced.124 In a recent surgical series, Huang, et al.125 reported that HH was controlled in all 63 patients with refractory HH who underwent thoracoscopic mesh onlay reinforcement to repair diaphragmatic defects (mesh covering alone was used in 47 patients and mesh with suturing was used in 16 patients). Four patients experienced recurrence after a median 20.5 months of follow-up examinations. The 1-month mortality rate was 9.5% (6 of 63 patients). Underlying impaired renal function and MELD scores were associated with increased 3-month mortality in 16 patients. The main causes of 3-month mortality were septic shock, acute renal insufficiency, gastrointestinal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, and ischemic bowel. Although these minimally-invasive approaches appear encouraging, further evaluation in additional experienced centers is warranted to corroborate these results and approaches in these high-risk surgical patients.

Peritoneovenous shunts or pleurovenous shuntingThe peritoneovenous shunt is an implantable device that carries the ascites or hydrothorax into the systemic circulation through a surgically placed subcutaneous plastic cannula with a one-way pressure valve.126 It has been reported as an appropriate alternative treatment for managing refractory ascites.126 However, peritoneovenous shunt for the management of HH has been used in a limited number of patients, with conflicting results.127,128 It has been noted that the lower pressure in the pleural cavity than in the central vein in case of without ascites usually makes the peritoneovenous shunt ineffective for treatment of HH.129 In addition, concerns about serious complications associated with this procedure including infection, diffuse intravascular coagulation, hepatic encephalopathy and lack of efficacy due to frequent occlusion have led other investigators to conclude that this method has limited effectiveness.128 Therefore, peritoneovenous shunt for the treatment of HH was abandoned nearly a decade ago.

The alternative Denver pleurovenous shunt includes a unidirectional pump, which was placed subcutaneously and additionally allowed external manual compression to move fluid.129,130 Use of the Denver shunt is therefore indicated in cases in which the fluid has to be moved against higher pressure.127,131 It can be inserted percutaneously under local anesthesia, and shunt patency can be maintained, mechanical occlusion and infection can be managed by shunt revision, and HH can be effectively controlled with only minutes of daily pumping.130,132,133 However, complete aspiration of pleural fluid may result in pleuritic chest pain, and shunt insertion must be performed with great care to prevent air embolism.134 Several cases have reported with successful long-term application of a Denver pleurovenous shunt in the treatment of HH, as an “alternative” therapy in selected patients.131–133

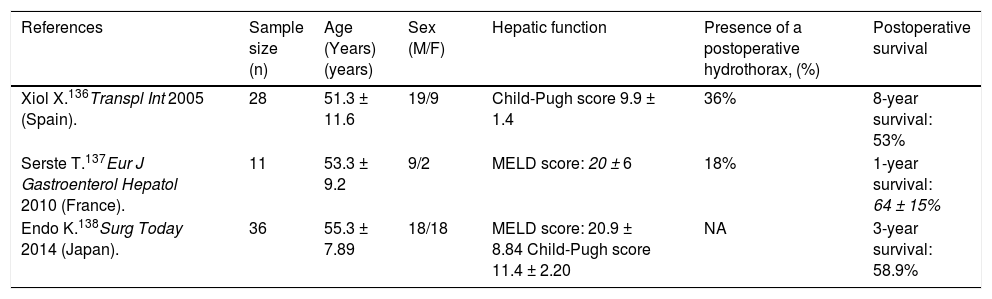

Liver transplantationLiver transplantation is the treatment of choice for decompensated cirrhosis, and thereby provides the best management for HH.1,135 The outcome of HH (refractory or not) following liver transplantation is very favorable (Table 3).135 Xiol, et al.136 reported 28 HH patients versus a control group of 56 patients transplanted. Five patients were considered with refractory HH; no patient received TIPS or had chest tube drainage. HH persisted in 36% of patients at one month after transplant, but had resolved in all patients within 3 months of transplant. Long-term outcomes were similar among patients with refractory HH and those with non-complicated HH. Serste, et al.137 described that the postoperative complications and survival were not different in HH (n = 11) compared to those with tense ascites and those with no HH (both groups had n = 11) matched for age, sex, year of transplant, and severity of cirrhosis. No significant differences in the duration of mechanical ventilation, intensive care unit stay, and inhospital stay, incidence of sepsis and early postoperative death were observed among three groups. One-year survival was also similar (64 ± 15% vs. 91 ± 9% vs. 63 ± 15%). Endo, et al.138 compared the outcomes of patients with (n = 36) and without (n = 201) uncontrollable HH and massive ascites requiring preoperative drainage who underwent liver transplantation. They found that the incidence of postoperative bacteremia was higher (55.6 vs. 46.7%, P = 0.008) and the 1- and 3-year survival rates were lower (1 year: 58.9 vs. 82.9%; 3 years: 58.9 vs. 77.7%; P = 0.003) in patients with uncontrollable HH and massive ascites than those without. They suggested that postoperative infection control may be an important means of improving the outcome for patients with uncontrollable HH and massive ascites undergoing liver transplantation. These findings suggest that liver transplantation provides the best definitive treatment with significant long-term survival and should be considered in all patients.139

Results of liver transplantation in refractory hepatic hydrothorax.

| References | Sample size (n) | Age (Years)(years) | Sex (M/F) | Hepatic function | Presence of a postoperative hydrothorax, (%) | Postoperative survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xiol X.136Transpl Int 2005 (Spain). | 28 | 51.3 ± 11.6 | 19/9 | Child-Pugh score 9.9 ± 1.4 | 36% | 8-year survival: 53% |

| Serste T.137Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010 (France). | 11 | 53.3 ± 9.2 | 9/2 | MELD score: 20 ± 6 | 18% | 1-year survival: 64 ± 15% |

| Endo K.138Surg Today 2014 (Japan). | 36 | 55.3 ± 7.89 | 18/18 | MELD score: 20.9 ± 8.84 Child-Pugh score 11.4 ± 2.20 | NA | 3-year survival: 58.9% |

MELD: Model for End-Stage Liver Disease. NA: Not available.

HH is an infrequent complication of portal hypertension in patients with end-stage liver disease. Although the physiopathology of HH is not fully elucidated, transdiaphragmatic passage of ascetic fluid from the peritoneal to the pleural cavity through numerous diaphragmatic defects has been shown to be the predominant mechanism in the formation of HH. Although the diagnosis of HH can typically be based on clinical grounds in a patient with established cirrhosis and ascites who presents with a right-sided pleural effusion, a diagnostic thoracentesis is mandatory in all patients with pleural effusions to exclude the presence of infection or an alternate diagnosis. In cases where the diagnosis is uncertain, in particular when ascites is not detected or the hydrothorax is present on the left side, scintigraphic studies serum albumin can be helpful. Spontaneous bacterial empyema, the infection of a hydrothorax, can complicate HH and increase morbidity and mortality. Treatment of HH is primarily medical, with salt restriction and diuretics. However, medical management of this condition often fails and liver transplantation remains the ultimate definitive management paradigm. For patients who are not candidates and those who are waiting for a transplant, therapeutic thoracentesis, ITPC, TIPS, pleurodesis, and video-assisted thoracic surgery are useful tools to alleviate symptoms and prevent pulmonary complications in selected patients.

Financial DisclosureNone.

Competing InterestsThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations- •

HH: hepatic hydrothorax.

- •

ITPC: indwelling tunneled pleural catheter.

- •

MELD: models for end:stage liver disease.

- •

SBEM: spontaneous bacterial empyema.

- •

TIPS: transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

- •

VATS: videoassisted thoracoscopic surgery.