Occult HBV infection (OBI) is a specific form of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and has the possibility of developing into hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in adults. This study aimed to estimate the global prevalence of occult HBV infection in children and adolescents.

Materials and MethodsWe systematically searched PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane databases for relevant studies on the prevalence of OBI in children and adolescents. Meta-analysis was performed using STATA 16 software.

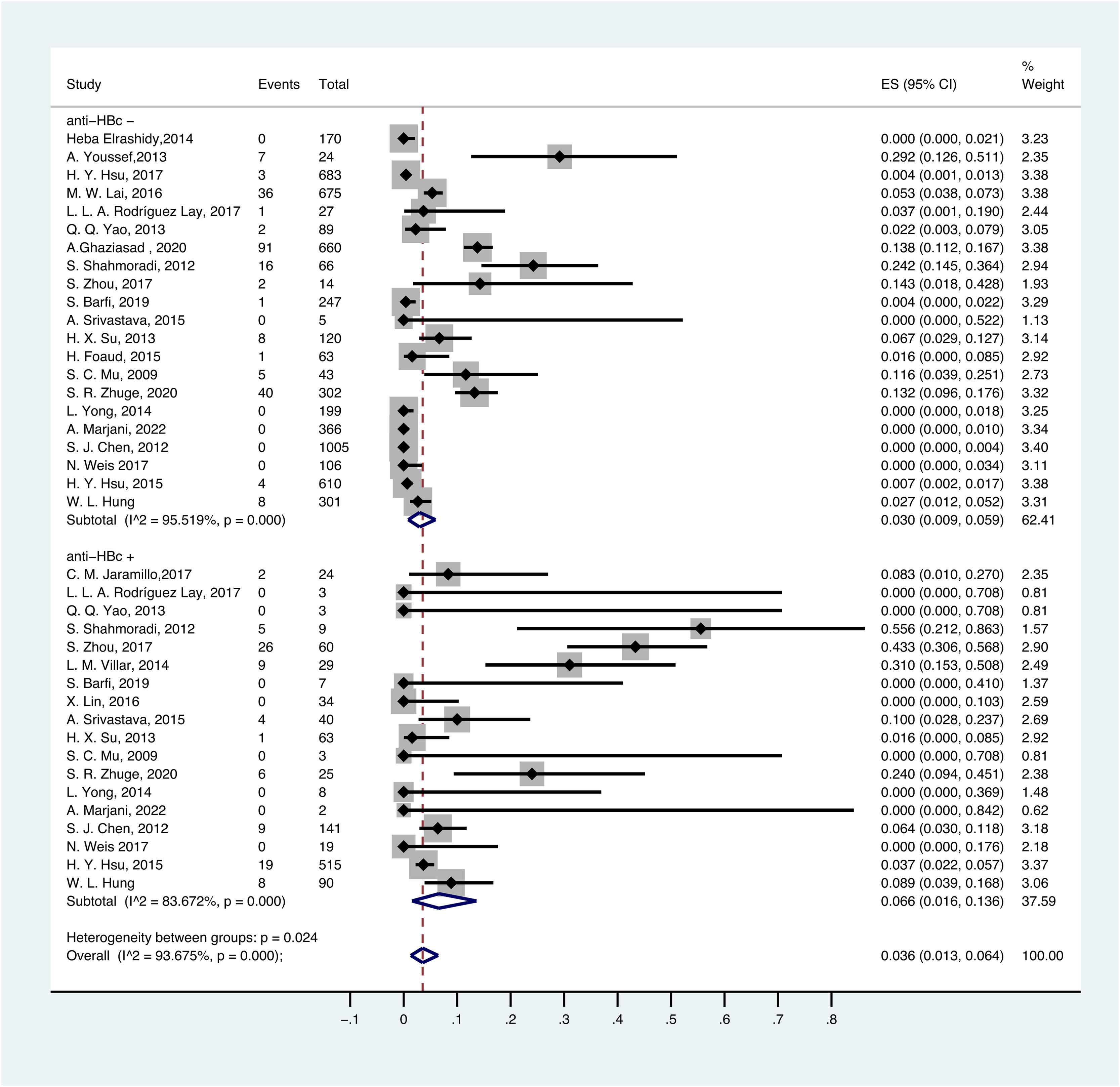

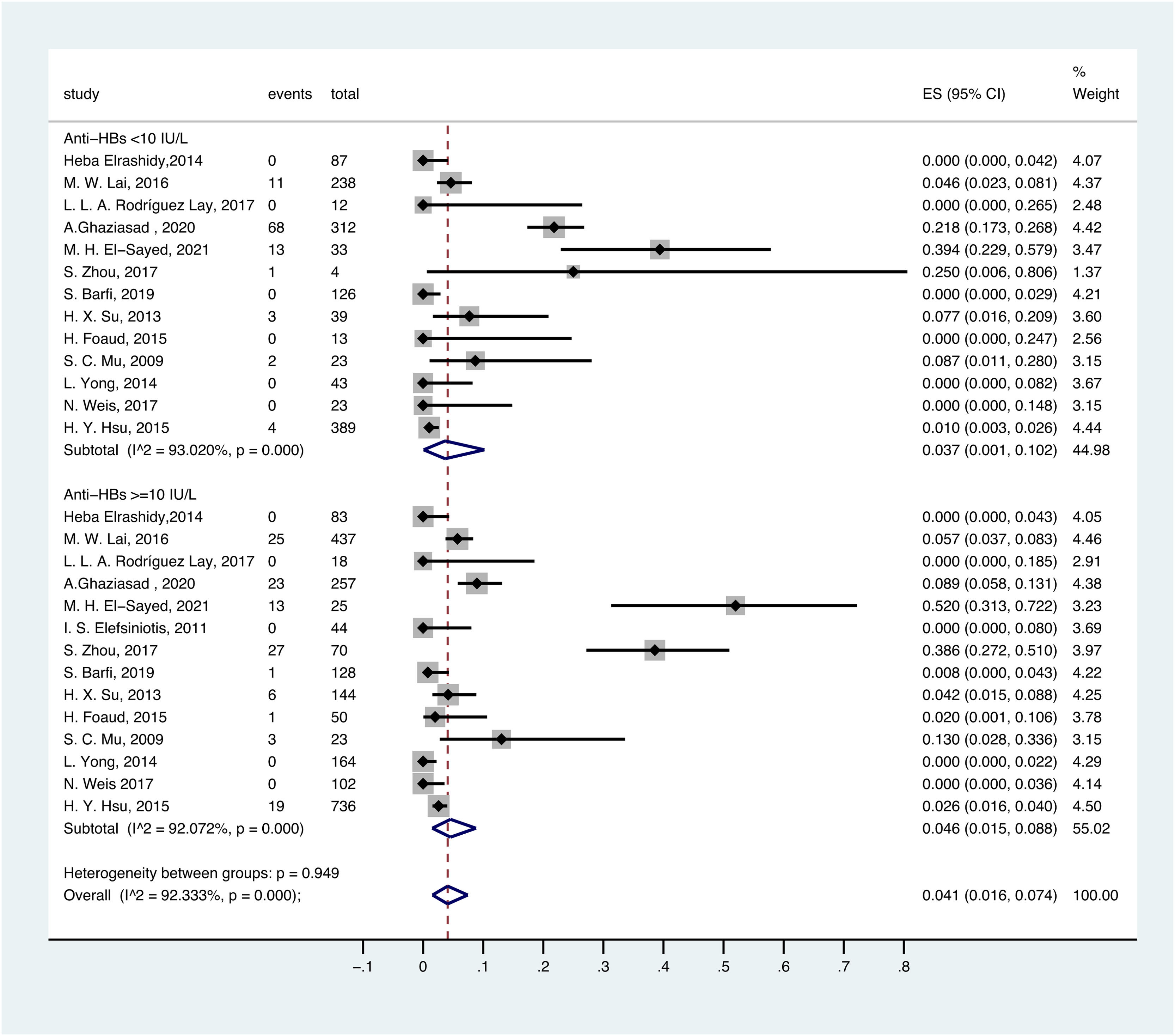

ResultsFifty studies were included. The overall prevalence of OBI in children and adolescents was 7.5% (95% CI: 0.050–0.103). In different risk populations, OBI prevalence was remarkably high in the HIV-infected population (24.2%, 95% CI: 0.000–0.788). The OBI prevalence was 0.8% (95% CI:0.000–0.029) in the healthy population, 3.8% (95% CI:0.012–0.074) in the general population, and 6.4% (95% CI: 0.021–0.124) in children born to HBsAg-positive mothers. Based on different serological profiles, the prevalence of OBI in HBsAg-negative and anti-HBc-positive patients was 6.6% (95% CI: 0.016–0.136), 3.0% (95% CI: 0.009–0.059) in HBsAg-negative and anti-HBc-negative patients, 4.6% (95% CI: 0.015–0.088) in HBsAg-negative and anti-HBs-positive patients, and 3.7% (95% CI: 0.001–0.102) in HBsAg-negative and anti-HBs-negative patients.

ConclusionsDespite HBV vaccination and hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG), OBI is common in children and adolescents in high-risk groups.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is an enveloped DNA hepadnavirus that is responsible for hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and even hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [1–2]. Despite expanded immunization and antiviral treatment, HBV infection is still a remarkable global health issue. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 296 million people had chronic HBV infection, and approximately 6 million children under five years old were infected with HBV worldwide in 2019 [3].

Occult HBV infection (OBI) is a specific form of HBV infection and is defined as the presence of HBV DNA in the liver or serum of individuals who test negative for HBsAg using currently available assays [4]. Many studies have demonstrated that mutations or deletions in the pre-S/S region of HBV may alter viral antigenicity and phenotype, which can lead to false-negative results of HBsAg [5–8]. OBI is classified into seropositive OBI (anti-HBc and/or anti-HBs positive) and seronegative OBI (anti-HBc and anti-HBs negative) based on the anti-HBc serostatus [4]. OBI has the pro-oncogenic properties of HBV and it has the possibility of developing into HCC in adults [9–11].

The incidence of OBI varies with the prevalence of HBV, and individuals from HBV hyper-endemic regions are more susceptible to occult HBV infection [12]. The majority of cases of HBV-infected children occur in the perinatal or early childhood period. In addition, HBV vaccination is not completely effective, and children born to mothers with OBI or HBV infection are likely to have occult HBV infections [13].

Some studies have reported the global prevalence of OBI in adults. However, no systematic review for OBI in children and adolescents has been conducted. Therefore, this meta-analysis aims to estimate the global prevalence of OBI in children and adolescents.

2Materials and methods2.1Search strategy and study selectionFor this meta-analysis, we systematically searched four databases (PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, and Web of Science) to collect relevant studies about the prevalence of OBI in children and adolescents published up to February 03, 2023.

We used the following terms to search for studies: “occult hepatitis B virus infection” and its synonyms, “children” and its synonyms (the full search strategy is available in the Supplementary Information).

All included studies were required to meet the following criteria: 1) defined OBI as the presence of HBV DNA in serum and/or liver tissue without detectable HBsAg, 2) assessed the prevalence of OBI, 3) sample size ≥ 10, 4) included HBsAg-negative children and adolescents (age ≤ 18 years old), 5) written in English, and 6) could be retrieved in full-text. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) not pediatric population, 2) HBV-DNA was not tested, 3) data were duplicated or/and cannot be extracted, 4) case reports, editorial letters, conference abstracts, and reviews, and 5) studies were retracted.

Two independent reviewers (WJY and XHM) selected potentially eligible studies based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria by screening the title and abstract. The full texts of studies deemed eligible were reviewed thoroughly. Any discrepancies in study selection were resolved through discussion.

2.2Data extractionTwo reviewers used an Excel form to record the following information from eligible studies: first author, year of publication, study type, study region, sample size, and participant characteristics (number of OBI patients, number of anti-HBc-positive patients, and population group).

2.3Quality assessmentTwo reviewers (WJY and XHM) independently assessed the quality of the eligible studies using the method described in a previous study [14]. This assessment method includes 7 items divided into three dimensions: sample size, laboratory methods, and external validity. Any disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer (HJY).

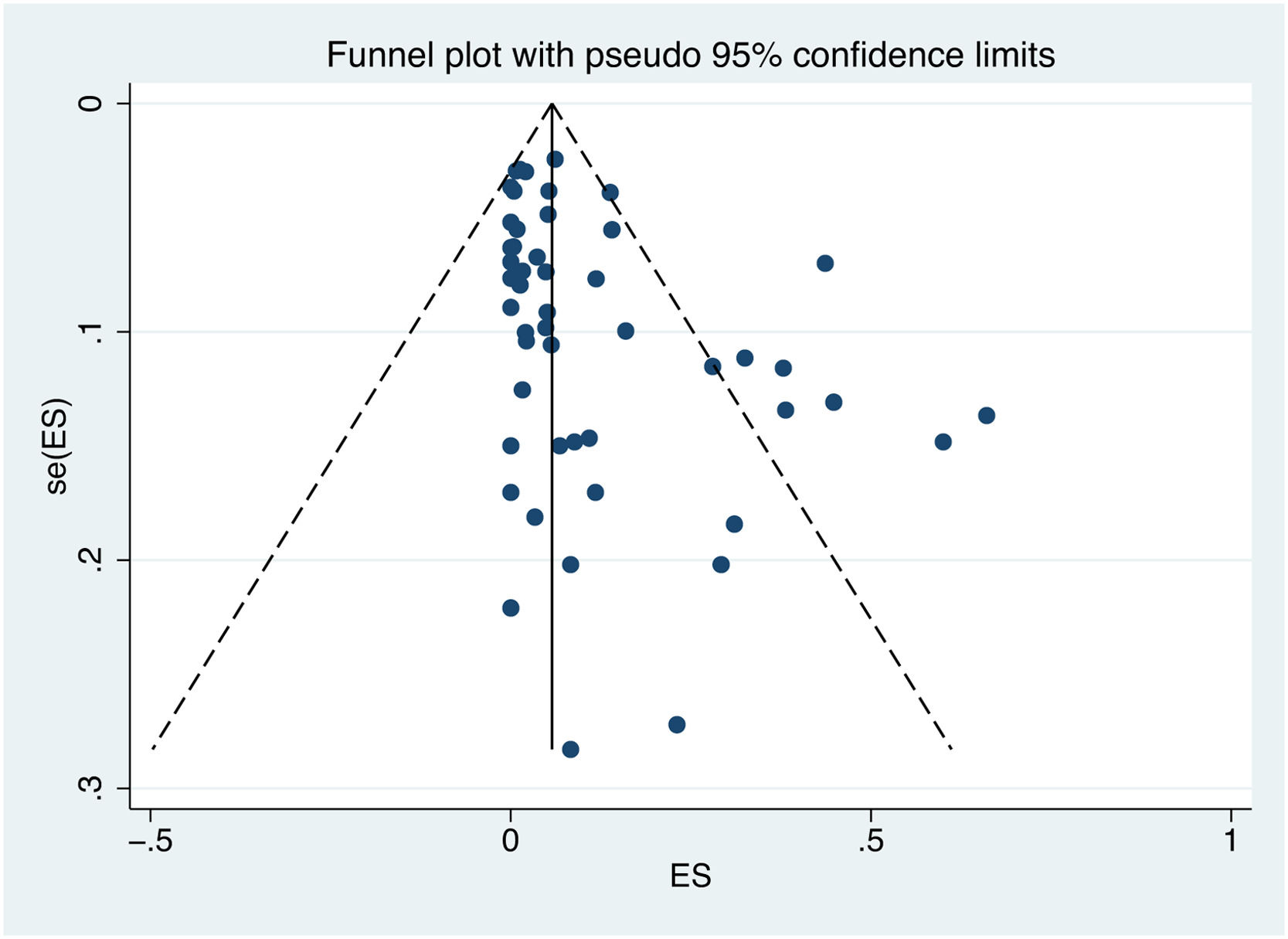

2.4Statistical analysisThe pooled prevalence of OBI was calculated with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Heterogeneity of studies was assessed by the Cochrane Q test and quantified by I2 values. A P value of the Q test < 0.1 or/and I2 ≥ 75% was identified as high heterogeneity [15]. A random-effect model was applied for statistical analysis. Subgroup analysis was performed to determine the source of heterogeneity. Otherwise, a fixed-effect model was performed. Publication bias was assessed by a funnel plot and Egger's test. If the funnel plot is asymmetric and the P value of Egger's test is less than 0.05, publication bias may exist. Statistical analysis was conducted by STATA version 16.0 software (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

2.5Ethical statementsThis systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines. The protocol was not registered.

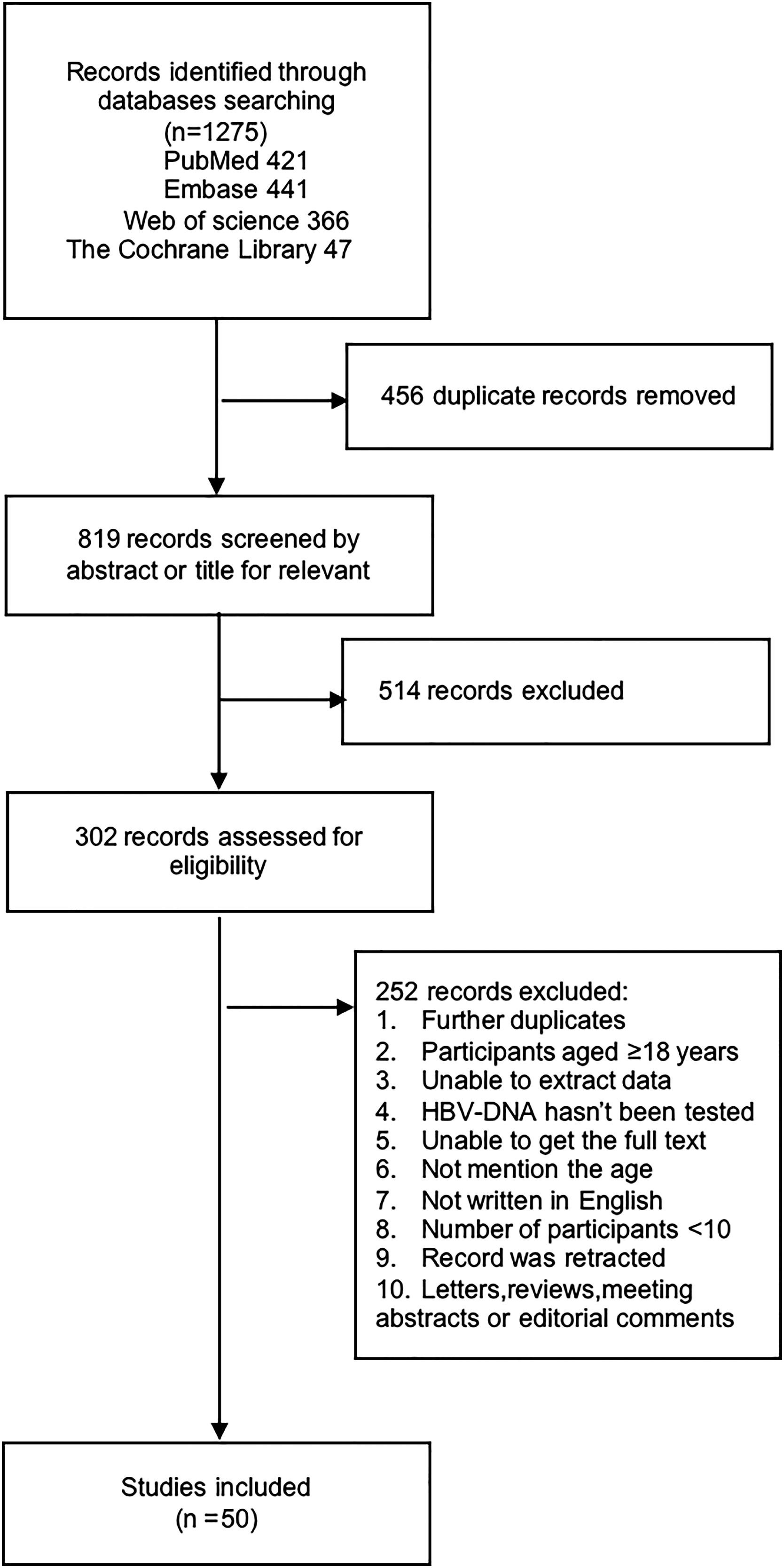

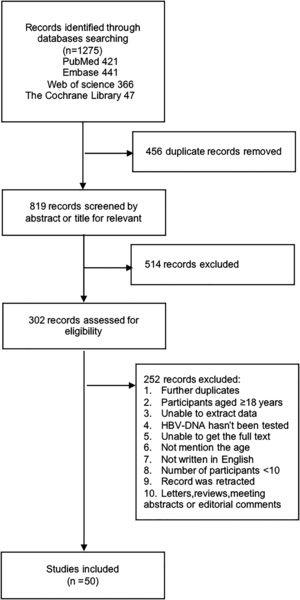

3ResultsA total of 1275 studies were obtained from the initial search of four online databases: 421 from PubMed, 441 from Embase, 366 from Web of Science, and 47 from the Cochrane Library. A total of 456 studies were removed because of duplication, 514 studies were excluded after screening the titles and abstracts, and 302 studies were retrieved to read the full-text for further evaluation. Ultimately, 50 studies that met the inclusion criteria were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis. The details of the study selection process are shown in Fig. 1.

3.1Characteristics of the included studiesThe main characteristics of the 50 included studies are described in Table 1 [13,16–64]. Overall, a total of 12977 HBsAg-negative participants from 50 studies were included, including 743 OBI patients. The majority of included studies (31/50) were cross-sectional studies, 15 were cohort studies, 2 were clinical trials, and 2 were case-control studies. Of the 50 studies included, 27 studies were conducted in Asia, 14 in Africa, 5 in Europe, 2 in South America, and 2 in North America.

Characteristic of the studies used in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

| First author | Publication year | Type of study | Location | Group | Occult HBV infection | Sample size | Anti-HBc+ | Serological criteria to test for OBI | OBI prevalence (total OBI / number tested for HBV DNA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. Elrashidy [16] | 2014 | Cohort | Egypt | Healthy/diabetes population | 0 | 170 | 0 | HBsAg-/Anti-HBc- | 0.0% |

| A. Youssef [17] | 2013 | Cross-sectional | Egypt | Acute hepatitis | 7 | 24 | 0 | HBsAg- | 29.2% |

| C. M. Jaramillo [18] | 2017 | Cross-sectional | Colombia | General population | 2 | 24 | 24 | HBsAg-/Anti-HBc+ | 8.3% |

| G. Gachara [19] | 2017 | Cross-sectional | Cameroon | HIV infected population | 4 | 34 | NR | HBsAg- | 11.8% |

| H. Y. Hsu [20] | 2017 | Cross-sectional | Taiwan | General population | 3 | 683 | 0 | HBsAg-/Anti-HBc- | 0.4% |

| Z. X. Chen [21] | 2017 | Cohort | China | Born to HBsAg-positive mothers | 3 | 185 | NR | HBsAg- | 1.6% |

| E. Seremba [22] | 2017 | Cross-sectional | Uganda | Born to HIV or HBV infected /healthy mother | 0 | 20 | NR | HBsAg- | 0.0% |

| M. W. Lai [23] | 2016 | Cross-sectional | Taiwan | Full vaccinated population | 36 | 675 | 0 | HBsAg-/Anti-HBc- | 5.3% |

| L. L. A. Rodríguez Lay [24] | 2017 | Cross-sectional | Cuba | Born to HBsAg-positive mothers | 1 | 30 | 3 | HBsAg- | 3.3% |

| E. Amponsah-Dacosta [25] | 2015 | Cohort | South Africa | Non-HIV/HIV infected population with exposure to HBV | 35 | 53 | NR | HBsAg- | 66.0% |

| Q. Q. Yao [26] | 2013 | Cohort | China | Born to HBI/Non-HBI mother | 2 | 92 | 3 | HBsAg- | 2.2% |

| Z. N. A. Said [27] | 2009 | Case-control | Egypt | Population with haematological disorders and malignancies | 21 | 55 | NR | HBsAg- | 38.2% |

| A. Ghaziasadi [28] | 2020 | Cross-sectional | Iran | General population | 91 | 660 | 0 | HBsAg-/Anti-HBc- | 12.8% |

| N. S. Mohamed [29] | 2020 | Case-control | Egypt | Frequently Blood Transfused population | 27 | 45 | NR | HBsAg- | 60% |

| M. Dapena [30] | 2013 | Cross-sectional | Spain | HIV-infected population | 0 | 251 | NR | HBsAg- | 0 |

| S. Shahmoradi [31] | 2012 | Cross-sectional | Iran | born to HBsAg-positive mothers | 21 | 75 | 9 | HBsAg- | 28% |

| M. H. El-Saye [32] | 2021 | Cohort | Egypt | Polytransfused Children with hematologic malignancy | 26 | 58 | 8 | HBsAg- | 44.8% |

| I. S. Elefsiniotis [33] | 2011 | Cross-sectional | Greece,Russia, Bulgaria,Romania, and Serbia | Born to chronic HBV infected mother | 0 | 44 | 32 | HBsAg- | 0 |

| S. Barfi [34] | 2019 | Cohort | Iran | ASD/healthy popolation | 1 | 254 | 7 | HBsAg- | 0.4% |

| S. Zhou [35] | 2017 | Cross-sectional | China | born to HBsAg positive mothers | 28 | 74 | NR | HBsAg- | 37.8% |

| L. M. Villar [36] | 2014 | Cross-sectional | Brazil | General population | 9 | 29 | 29 | HBsAg-/Anti-HBc+ | 31.0% |

| X. Lin [37] | 2016 | Cross-sectional | China | General population | 0 | 34 | 34 | HBsAg-/Anti-HBc+ | 0 |

| X. Qi [38] | 2023 | Cross-sectional | China | General population | 103 | 1679 | NR | HBsAg- | 6.1% |

| M. R. Aghasadeghi [39] | 2020 | Cross-sectional | Iran | General population | 0 | 742 | 3 | HBsAg- | 0 |

| O. Shaker [40] | 2012 | Cohort | Egypt | Transfused population with thalassemia | 26 | 80 | NR | HBsAg- | 32.5% |

| A. Srivastava [41] | 2015 | Cross-sectional | India | Population with chronic liver disease | 4 | 45 | 40 | HBsAg-/anti-HBc+/or anti-HBs+ | 8.9% |

| W. L. Hung [42] | 2019 | Cohort | Taiwan | Healthy/Non A to E hepatitis/ CHC population | 22 | 422 | 90 | HBsAg- | 5.2% |

| G. Beykaso [43] | 2022 | Cross-sectional | Ethiopia | General population | 1 | 12 | 12 | HBsAg-/Anti-HBc+ | 8.3% |

| G. Y. Minuk [44] | 2005 | Cross-sectional | Canada | General population | 6 | 119 | NR | HBsAg- | 5.0% |

| H. X. Su [45] | 2013 | Cross-sectional | China | Born to HBsAg positive mother | 9 | 183 | 63 | HBsAg- | 4.92% |

| H. Foaud [46] | 2015 | Cohort | Egypt | born to HBsAg-positive mothers | 1 | 63 | 0 | HBsAg- | 1.6% |

| S. C. Mu [47] | 2009 | Cross-sectional | Taiwan | HBV vaccinated children | 5 | 46 | 3 | HBsAg- | 10.9% |

| K.Yokoyama [48] | 2017 | Cross-sectional | Japan | born to HBsAg-positive mothers | 2 | 158 | NR | HBsAg- | 0 |

| H. Y. Hsu [49] | 2021 | Clinical trial | Taiwan | born to HBsAg-positive mothers | 8 | 220 | NR | HBsAg- | 3.6% |

| A. Q. Hu [50] | 2021 | Cohort | China | Born to HBI/Non-HBI mother | 3 | 328 | NR | HBsAg- | 0.9% |

| H. Su [51] | 2017 | Cross-sectional | China | General population | 15 | 1192 | NR | HBsAg- | 1.3% |

| S. R. Zhuge [52] | 2020 | Cohort | China | born to HBsAg-positive parents | 46 | 327 | 25 | HBsAg- | 14.1% |

| L. Yong [53] | 2014 | Cross-sectional | China | born to HBsAg-positive mothers | 0 | 207 | 8 | HBsAg- | 0 |

| S. J. Chen [54] | 2012 | Cross-sectional | China | Healthy population | 9 | 1146 | 141 | HBsAg- | 0.8% |

| A. Marjani [55] | 2022 | Cross-sectional | Iran/Afghanistan | Working population | 0 | 368 | 2 | HBsAg- | 0 |

| T. Utsumi [56] | 2010 | Cross-sectional | Indonesia | General population | 5 | 89 | NR | HBsAg-/anti-HBs+ and/or anti-HBc+ | 5.6% |

| H. E. Raouf [57] | 2015 | Cohort | Egypt | HCV positive/negative cancer population | 16 | 100 | NR | HBsAg- | 16% |

| A. Eilard [58] | 2019 | Cross-sectional | Sweden | born to HBsAg-positive mothers | 3 | 44 | NR | HBsAg- | 6.8% |

| N. Weis [59] | 2017 | Cross -sectional | Denmark | born to CHB mothers | 0 | 125 | 19 | HBsAg- | 0 |

| A. Walz [13] | 2009 | Cross-sectional | Germany | born to Anti-HBc mothers | 5 | 103 | NR | HBsAg- | 4.9% |

| C.Chakvetadze [60] | 2011 | Cohort | Mayotte, France | born to HBsAg-positive mothers | 2 | 99 | NR | HBsAg- | 2.0% |

| C. Pande [61] | 2013 | Clinical trial | India | born to HBsAg-positive mothers | 89 | 204 | NR | HBsAg- | 43.6% |

| A. Y. Li [62] | 2020 | Cohort | China | born to HBsAg and HBeAgpositive mothers | 20 | 169 | NR | HBsAg-/Anti-HBs+ | 11.8% |

| C. J. Hoffmann [63] | 2014 | Cohort | South Africa | born to CHB/Non-CHB mothers living with HIV | 3 | 13 | NR | HBsAg- | 23.1% |

| H. Y. Hsu [64] | 2015 | Cross-sectional | Taiwan | General population | 23 | 1125 | 515 | HBsAg- | 2.0% |

According to the risk of acquiring HBV infection, participants enrolled in the included studies were divided into four populations, including the healthy population in 4 studies, the general population in 12 studies, the population born to HBsAg-positive mothers in 19 studies, and the HIV-infected population in 3 studies.

3.2Quality assessmentThe details of the methodological quality assessment are illustrated in Supplement Table 1. 14 studies were considered at low risk of bias, 20 studies were considered at moderate risk of bias, and 16 studies were considered at high risk of bias.

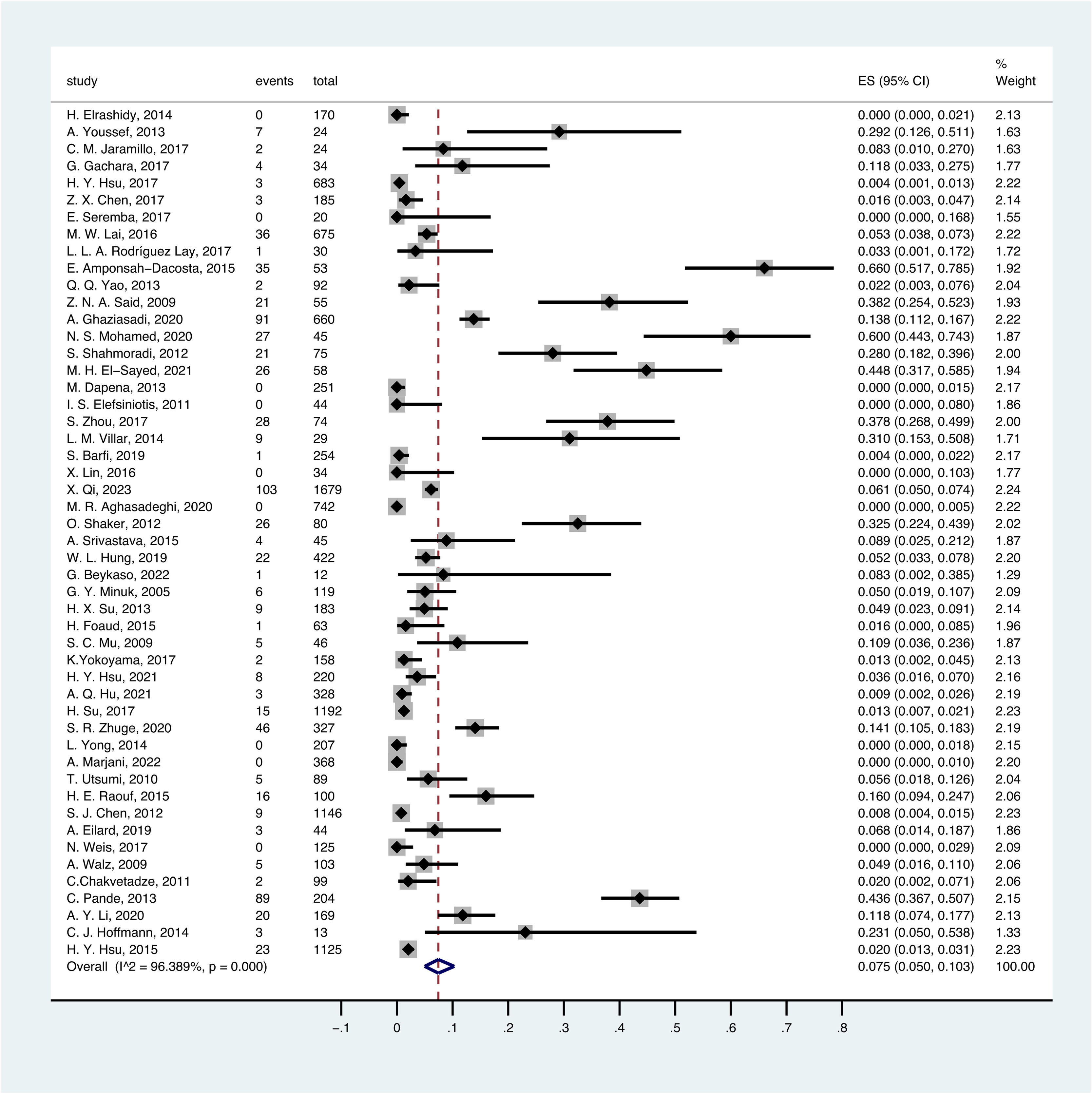

3.3Overall OBI prevalence in childrenA random-effect model was performed to estimate the overall prevalence of occult HBV infection in children and adolescents because it has significantly high heterogeneity (I2 = 96.389%, p < .1).

The overall pooled OBI prevalence in children and adolescents was 7.5% (95% CI: 0.050–0.103) (Fig. 2). Based on different serological criteria, the overall prevalence of OBI was as follows: 7.9% (95% CI: 0.050–0.114) for HBsAg-negative, 3.2% (95% CI: 0.000–0.108) for HBsAg-negative and anti-HBc-negative, 8.9% (95% CI: 0.006–0.232) for HBsAg-negative and anti-HBc-positive, and 7.3% (95% CI: 0.039–0.114) for HBsAg-negative and other criteria.

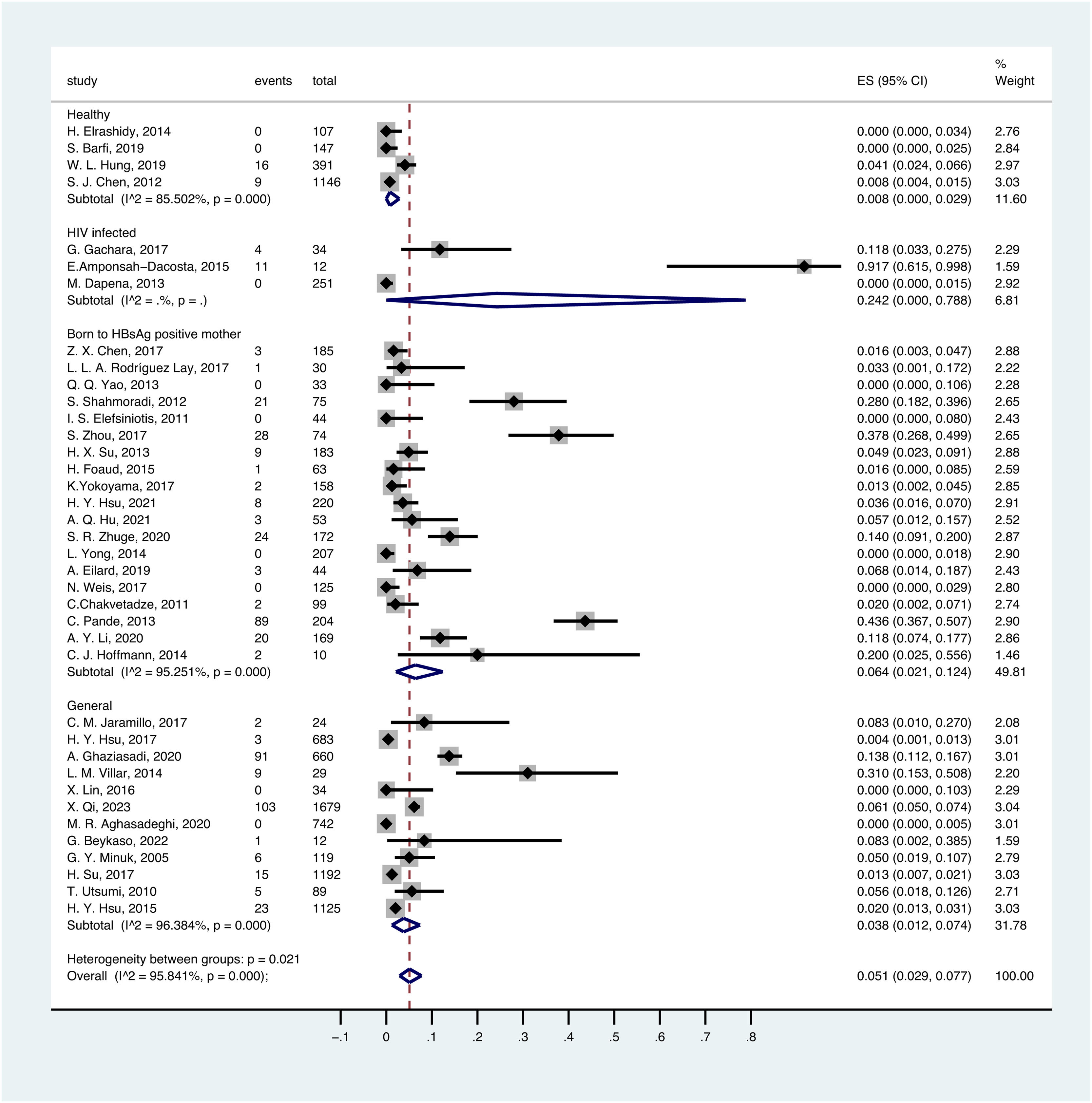

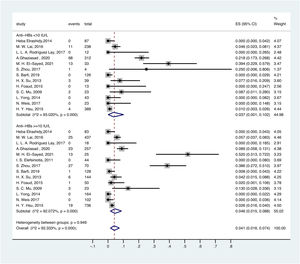

3.4OBI prevalence in different populationsThere was a significant variation in different populations. The prevalence of OBI in the healthy population was estimated to be 0.8% (95% CI:0.000–0.029), with a total of 1791 participants from 4 prevalence datasets. The prevalence of OBI in the general population was estimated to be 3.8% (95% CI:0.012–0.074), with a total of 6388 participants from 12 prevalence datasets. The prevalence of OBI in the population with HIV infection was 24.2% (95% CI: 0.000-0.788), with a total of 297 participants from 3 prevalence datasets. The prevalence of OBI in children born to HBsAg-positive mothers was 6.4% (95% CI: 0.021–0.124), with a total of 2148 participants from 19 prevalence datasets (Fig. 3).

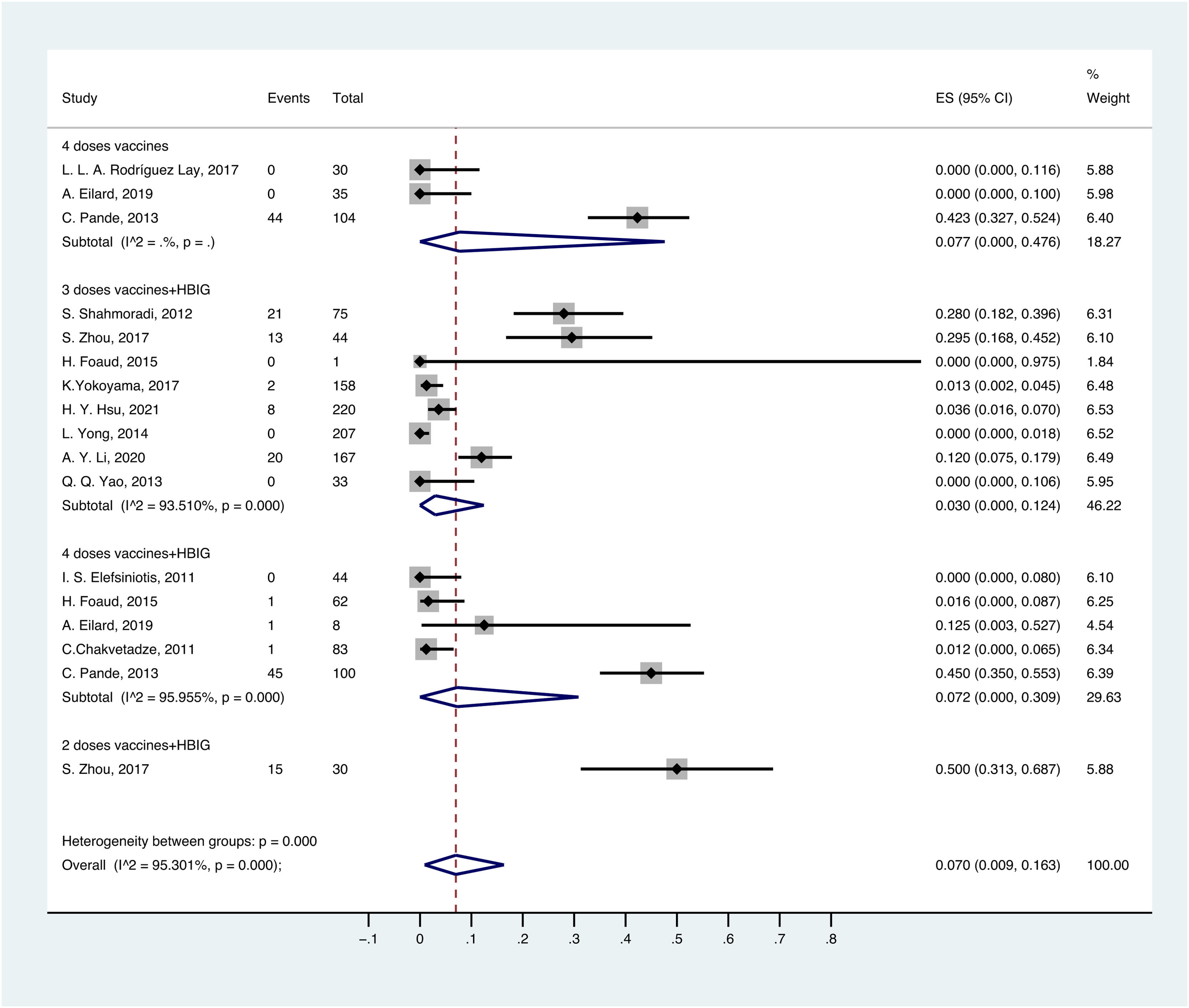

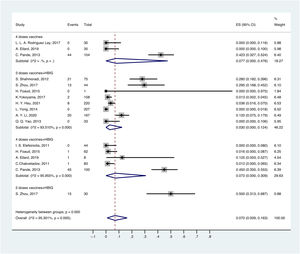

OBI prevalence varied with different methods of passive-active immunoprophylaxis. For the population born to HBsAg-positive mothers, the prevalence of OBI was 3.0% (95% CI: 0.000–0.124) in children vaccinated with 3 doses of vaccine and HBIG, followed by 7.2% (95% CI: 0.000–0.309) in children vaccinated with 4 doses of vaccine and HBIG, 7.7% (95% CI: 0.000–0.476) in children vaccinated with 4 doses of vaccine, and 50% (95% CI: 0.313–0.687) in children vaccinated with 2 doses of vaccine and HBIG (Fig. 4).

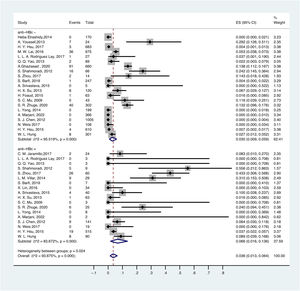

3.5OBI prevalence in different serological profiles of HBV infectionThe prevalence of OBI varied with HBV serological status. The prevalence of OBI in HBsAg-negative and anti-HBc-positive participants was 6.6% (95% CI: 0.016–0.136), with a total of 1075 participants from 18 prevalence datasets. The prevalence of OBI in HBsAg-negative and anti-HBc-negative participants was 3.0% (95% CI: 0.009–0.059), with a total of 5775 participants from 21 prevalence datasets (Fig. 5).

For anti-HBs in serum, ≥ 10 mIU/ml was considered positive. Thus, the prevalence of OBI in HBsAg-negative and anti-HBs-positive participants was 4.6% (95% CI: 0.015–0.088), with a total of 2281 participants from 14 prevalence datasets. The prevalence of OBI in HBsAg-negative and anti-HBs-negative participants was 3.7% (95% CI: 0.001–0.102), with a total of 1342 participants from 13 prevalence datasets (Fig. 6).

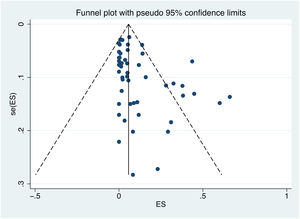

3.6Publication biasPublication bias was assessed using Egger's test and a visual inspection of the funnel plot. The shape of the funnel plot is not symmetrical, indicating a potential bias (Fig. 7). The results of Egger's test (p value = 0.002) confirm the existence of publication bias.

4DiscussionThis is the first meta-analysis to estimate the global prevalence of OBI in children and adolescents. The prevalence of OBI varies in different populations. In this study, we found that the prevalence of OBI was 0.8% in the healthy population and 3.8% in the general population. The prevalence of OBI in children born to HBsAg-positive mothers was almost twice that in the general population. OBI prevalence was remarkably higher in the HIV-infected population than in the population born to HBsAg-positive mothers.

Mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of HBV is a key route of transmission. WHO recommends that children born to HBsAg-positive mothers should receive HBIG and at least 3 doses of hepatitis B vaccine to prevent MTCT [65]. However, there is still a residual risk of HBV infection in children born to HBsAg-positive mothers despite neonatal passive-active immunoprophylaxis. In our study, we found that the usage of HBIG and 3 doses of hepatitis B vaccine was the most effective method to prevent children born to HBsAg-positive mothers from occult HBV infection. We need studies of large samples to confirm this result. In addition, maternal HBeAg status and HBV DNA load had positive correlations with the MTCT incidence of HBV [66]. However, Li et al[67] found that maternal age, HBsAg titer, HBeAg status, HBV DNA viral load, alanine aminotransferase level, child's sex, feeding pattern, HBIG dosage, birth weight, and anti-HBs level had no significant association with OBI incidence in 7-month-old infants. These controversies need further research to resolve. In addition, some studies have indicated that OBI in children born to HBsAg-positive mothers may be transient or become overt after several years [24,35,58]. Therefore, long-term follow-up is needed in children born to HBsAg-positive mothers.

Considering the overlap of transmission routes, HBV infection is common in people living with HIV. A meta-analysis study [68] indicated that the global OBI prevalence in HIV-infected patients was 16.26%. Kajogoo et al[69] reported that the prevalence of OBI was 12.4% among HIV-infected individuals in Africa. Xie et al[70] reported that 9% of patients living with HIV in Asia had occult HBV infection. While we found that the prevalence of OBI was 24.2% in the HIV-infected population in our study. The following reasons may be responsible for this: 1) HIV-infected children have inadequate expression of cytokines related to the immune response and inadequate production of anti-HBs, which may lead to HBV infection [71]. 2) HIV-infected patients have immune dysfunction, which may lead to HBV reactivation [72]. 3) HBV-resistance mutations may occur when HIV-infected patients receive lamivudine-based therapies [73]. 4) Low CD4 count is related to OBI incidence in HIV-infected patients [74]. However, one study had the opposite result, in which the occurrence of OBI was not concerned with CD4 count [75]. Therefore, detection of HBV DNA should be a routine examination in the HIV-infected population. Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) with 2 anti-HBV nucleos(t)ide analogs is recommended for HIV-infected patients with OBI [76].

Anti-HBc is considered a sign when people have been exposed to HBV, and it can be detected before the appearance of HBsAg [77]. In this study, we found that the prevalence of OBI in the HBsAg-negative and anti-HBc-positive participants was significantly higher than that in the HBsAg-negative and anti-HBc-negative participants. This result was in line with two meta-analysis studies that reported 20.1% vs. 8% and 51% vs. 19%, respectively [14,78]. Thus, the detection of anti-HBc is recommended for screening OBI in underdeveloped regions. For anti-HBs, the prevalence of OBI in HBsAg-negative and anti-HBs-positive subjects was similar to that in HBsAg-negative and anti-HBs-negative subjects. However, among children born to HBsAg-positive mothers, the OBI prevalence in infants with low anti-HBs (< 100 mIU/mL) was higher than that in infants with high anti-HBs (≥ 100 mIU/mL) [62] . Therefore, a high-risk population may need a booster vaccine and/or a higher dosage of vaccine.

Our study had some limitations. First, we used a homemade assessment tool to evaluate the quality of articles, and the majority of included studies were considered at moderate risk. Second, there was significant heterogeneity that we could not explain, although we performed subgroup analyses. Third, we cannot evaluate the prevalence of OBI in the HCV-infected population and transfused population, because there were not enough studies. Fourth, the studies included children born to HBsAg-positive mothers were from different countries with different methods of HBV prophylaxis at birth. Last, the sensitivity and specificity of the HBsAg assay was improved gradually, and the methods of HBV DNA detection were different in the included studies. No gold standards can be followed to estimate OBI prevalence between the studied periods now.

Despite the above limitations, the main strength of our study was that the prevalence of OBI in children born to HBsAg-positive mothers was first estimated. We also accounted the prevalence of OBI according to the anti-HBc/anti-HBs serostatus.

5ConclusionsThis review first summarized the global prevalence of OBI in children and adolescents. With the popularity of the HBV vaccine and HBIG, children still have the chance to be infected with occult HBV. OBI prevalence varies with different populations. In high-risk groups, OBI prevalence is remarkably high. We should pay more attention to OBI in children and adolescents.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributionsJiaying Wu developed the study protocol and wrote the manuscript. Jiaying Wu and Hongmei Xu performed the search, screened the articles and data analysis. Jiaying Wu, Hongmei Xu, and Jiayao He performed quality assessment. All authors reviewed and agreed with the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability statementData are available upon request, please contact author for data requests.