Background. The relationships between the metabolic parameters and the endoscopic findings of esophageal varices have been poorly investigated. We investigated the association of the branched-chain amino acids to tyrosine ratio (BTR) with the severity of liver fibrosis and esophageal varices.

Material and Methods. We studied hepatitis C virus (HCV)-positive chronic liver disease patients who had undergone liver biopsy (n = 149). The relationship between the BTR values and the liver fibrotic stage was investigated. We also studied whether the BTR value was associated with the presence and bleeding risk of varices in patients with HCV-related compensated cirrhosis.

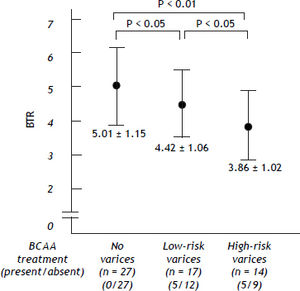

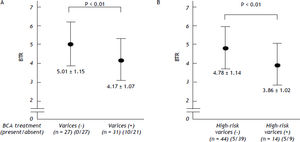

Results. The mean values of the BTR decreased with the progression of the fibrosis (METAVIR score: F0-1: 6.40 ± 1.19; F2: 5.85 ± 1.33; F3: 5.24 ± 0.97, F4: 4.78 ± 1.14). In the 58 patients with HCV-related compensated cirrhosis, the mean values of the BTR decreased with the severity of varices (patients without varices: 5.01 ± 1.15, patients with a low-risk varices: 4.42 ± 1.06, patients with a high-risk varices: 3.86 ± 1.02). The BTR value was significantly lower in the patients with varices than in those without varices (4.17 ± 1.07 vs. 5.01 ± 1.15, P < 0.01). The BTR value was also significantly lower in the patients with a high risk of hemorrhage than in those with a low risk (3.86 ± 1.02 vs. 4.78 ± 1.14, P < 0.01). Furthermore, the BTR value was the most significantly different parameter, with the smallest P-value among all the factors examined, including the platelet count and albumin level.

Conclusion. A decreased BTR value was found to be associated with the progression of liver fibrosis and severity of varices.

In patients with liver cirrhosis, variceal hemorrhage due to portal hypertension is a severe complication that can occasionally cause an unfavorable prognosis. Three factors have been identified as conditions that are associated with a high risk of variceal bleeding: a large variceal size, red signs on the varices, and advanced liver disease (Child-Pugh class B or C status).1 Since esophagogastroduode- noscopy (EGD) is the gold standard method of evaluating variceal size and the presence of red signs, EGD should be performed in all cirrhotic patients.2,3

Despite the importance of EGD examination, this uncomfortable and expensive method is sometimes difficult for patients to accept. Therefore, several noninvasive biomarkers of liver fibrosis have so far been proposed to predict the presence and bleeding risk of varices in cirrhotic patients,4–6 because the progression of liver fibrosis is thought to be a major cause of portal hypertension. The major target population for a screening test should be the compensated cirrhotic patients without any clinical symptoms, rather than patients with obvious cirrhosis-related symptoms.6 However, in the case of cirrhotic patients with well-maintained liver function (Child-Pugh class A), there are few clinical parameters that have been reported to be related to the presence of treatment-requiring high-risk varices. In particular, the relationships between the metabolic parameters and the endoscopic findings of esophageal varices have up to now been poorly investigated, although the liver plays a central role in various functions associated with the metabolism.

It is well known that cirrhotic patients have low serum levels of branched-chain amino acids (BCAA), such as valine, leucine and isoleucine, and high serum levels of aromatic amino acids (AAA) such as tyrosine (Tyr) and phenylalanine. Therefore, the decreased serum ratio of BCAA and AAA (the Fisher’s ratio) in cirrhotic patients has been used as an indicator of an amino acid imbalance.7–9 The ratio of the BCAA and Tyr level (BCAA to Tyr ratio: BTR) has also been reported to decline in patients with liver cirrhosis, and the BTR can therefore be used as an easily measurable and inexpensive parameter to assess the amino acid imbalance, and is currently used in Japan.10,11

In the present study, we investigated the relationship between the histological grading of liver fibrosis and the value of BTR in patients with HCV-positive CLD. We further analyzed the values of BTR in HCV-related compensated cirrhotic patients with Child-Pugh class A status.

Material and MethodsIn order to examine the relationship between the BTR value and the progression of liver fibrosis in CLD patients, we studied 149 patients with HCV-related disease who had undergone a percutaneous liver biopsy from January 2008 to July 2011. The HCV infection was diagnosed by the detection of HCV antibodies and HCV-RNA in serum, and liver biopsy examinations were performed using the standard techniques. All liver samples were evaluated by well-trained pathologists at this institute, with an evaluation of the fibrosis stage and activity grade. Fibrosis was staged on a scale of F0–F4 (F0: no fibrosis; F1: portal fibrosis without septa; F2: portal fibrosis with rare septa; F3: numerous septa without cirrhosis. F4: liver cirrhosis) according to the METAVIR scoring system.12 The histological evaluation of the biopsy samples was also routinely performed in our department. All authors participated in the conferences about the histological evaluation, and the final results were confirmed by two authors (HE and HI) who received training for histological studies.

EGD was routinely performed in CLD outpatients at our institution according to the standard techniques. Esophageal varices detected by EGD was graded as I–IV according to the Paquet grading system,13 and the presence of red signs on the varices was also evaluated. Patients with large varices (grade III–IV) or small varices with red signs were categorized to be treatment-requiring (high-risk) varices. All HCV-related compensated (Child-Pugh class A) cirrhotic patients admitted to our department for the treatment of esophageal varices from January 2008 to July 2011 were included in the present study as the high-risk varices group. Liver cirrhosis as the cause of portal hypertension was diagnosed by histological criteria and/or by the clinical (laboratory, endoscopic and/or ultrasonographic) findings.

In order to collect the BTR values in the compensated (Child-Pugh class A) cirrhotic patients without high-risk varices, we enrolled consecutive HCV-positive CLD patients who had been diagnosed with cirrhosis (F4 stage) by liver biopsy, but who did not have treatment-requiring risky varices. The evaluation by EGD was performed within two months of the liver biopsy. The cirrhotic patients who did not have high-risk varices were divided into two groups; patients without detectable varices were classified as the no varices group and patients with small varices without red signs were classified as the low-risk varices group.

All blood samples were obtained on the day of liver biopsy or endoscopic treatment for esophageal varices, and patients without a complete data set on the day of the liver biopsy or the endoscopic treatment were excluded from the study. Patients with the following conditions were also excluded from the study: the presence of other liver diseases, using immunosuppressive therapy, hepatitis B virus co-infection and cases with insufficient liver tissue available for the evaluation of liver fibrotic staging. The study conformed to the ethical guidelines of the Helsinki declaration, and was approved by the ethics committees of the institutional review board. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients on admission.

Statistical analysisIn the present study, we attempted to clarify whether the BTR value was associated with the progression of liver fibrosis in HCV-related CLD. The data for the comparisons among the groups F0–1 vs. F2 vs. F3 vs. F4 were analyzed by a non-repeated measurements ANOVA, and statistical significance was further examined with the Bonferroni correction. We also investigated whether the BTR values differed among the three groups (no varices group, low-risk varices group and high-risk varices group). The data for the comparisons among the groups were analyzed by a non-repeated measurements ANOVA with a subsequent Bonferroni correction. In addition, we investigated whether the BTR differed between the groups with or without varices, and the differences in the baseline characteristics of the two groups were also investigated. We also evaluated whether the BTR values were different between the groups with and without high-risk (treatment-requiring) varices. Numerical variables with a normal distribution were expressed as the mean values ± SD, and the statistical significance of differences between two groups was evaluated using Student’s t-test. Numerical variables with an abnormal distribution were expressed as the median values (range) and the statistical analysis between two groups was done using the Mann-Whitney U test.

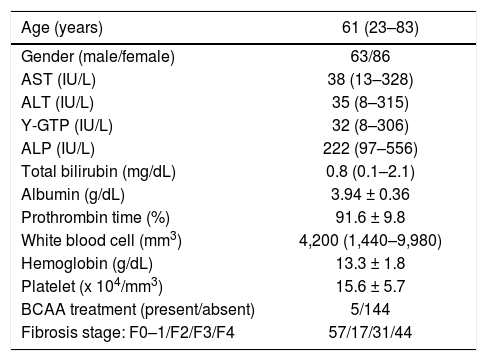

ResultsThe BTR values decreased with the progression of liver fibrosis in patients with HCV-related CLDA total of 149 patients with HCV-related CLD were included in this study to investigate the association between the BTR value and the histological progression of liver fibrosis, based on the criteria described in the Material and Methods section. The characteristics of the enrolled patients are summarized in table 1. The population included 63 (42%) males and 86 (58%) females, and the age of patients ranged from 23 to 83 years of age (median 61). The METAVIR liver fibrosis staging 12 showed that 92 (62%) patients had significant fibrosis (F2–F4), 75 (50%) patients had severe fibrosis (F3–F4) and 44 (30%) had cirrhosis (F4). Five out of a total of 149 patients were administered BCAA, and all five patients were histologically diagnosed to have cirrhosis by liver biopsy.

Characteristics of the 149 HCV-positive patients who received liver biopsy.

| Age (years) | 61 (23–83) |

|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 63/86 |

| AST (IU/L) | 38 (13–328) |

| ALT (IU/L) | 35 (8–315) |

| Y-GTP (IU/L) | 32 (8–306) |

| ALP (IU/L) | 222 (97–556) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.8 (0.1–2.1) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.94 ± 0.36 |

| Prothrombin time (%) | 91.6 ± 9.8 |

| White blood cell (mm3) | 4,200 (1,440–9,980) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.3 ± 1.8 |

| Platelet (x 104/mm3) | 15.6 ± 5.7 |

| BCAA treatment (present/absent) | 5/144 |

| Fibrosis stage: F0–1/F2/F3/F4 | 57/17/31/44 |

BCAA: branched-chain amino acids. Quantitative variables were expressed as the mean values ± SD or median (range).

The values of the BTR were decreased with the progression of the fibrosis (Figure 1), indicating that the value of the BTR is associated with the degree of liver fibrosis in HCV-associated CLD patients.

The values of BTR in relation to the METAVIR histological grading for liver fibrosis in patients with HCV-positive disease. The BTR value decreased as the fibrosis progressed. There was a significant difference between the F0/1 vs. F4, F3 and F2 groups. There was also a significant difference between the F2 vs. F4 and F2 vs. F3 groups.

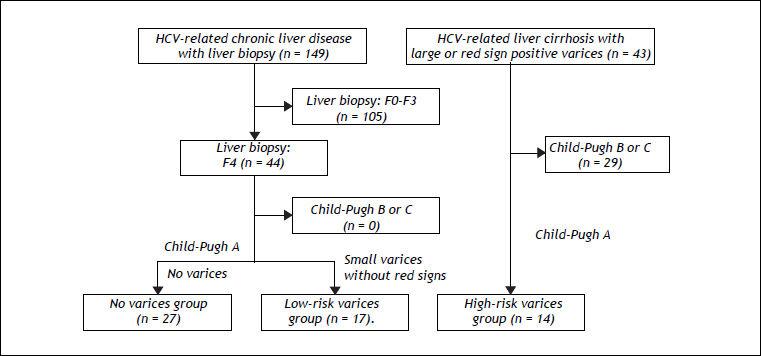

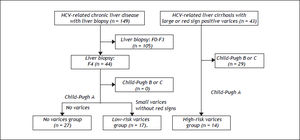

Since several biomarkers of liver fibrosis were reported to be associated with the presence and/or bleeding risk of esophageal varices,4–6 we examined whether the values of BTR were related to the severity of esophageal varices in patients with HCV-related compensated cirrhosis (Figure 2). In order to ascertain the characteristics of compensated cirrhotic patients with a low risk of variceal bleeding, we examined the 44 patients who were categorized as compensated cirrhotic patients (44 patients with a METAVIR score of F4, as shown in figure 1) with a low risk of variceal bleeding; 27 patients were diagnosed with liver cirrhosis without detectable varices (no varices group) and the remaining 17 patients had small varices without red signs (low-risk varices group). Of the CLD patients in our department, 43 HCV-positive patients were found to have a high risk of variceal bleeding because they had large varices (grade III-IV) or small varices with red signs. In these HCV-related cirrhotic patients, the Child-Pugh classification was grade A in 14 patients, grade B in 27 patients and grade C in two patients. The 14 patients with Child-Pugh class A were categorized as the HCV-related compensated cirrhotic patients with a high risk of variceal hemorrhage (high-risk varices group).

Algorithm for the classification of the patients with HCV-related compensated (Child-Pugh class A) cirrhosis. The 44 patients with a METAVIR score of F4 (shown in figure 1) were categorized as compensated cirrhotic patients with a low risk of variceal bleeding; 27 patients were diagnosed with liver cirrhosis without detectable varices (no varices group) and the remaining 17 patients had small varices without red signs (low-risk varices group). Of the CLD patients in our department, 43 HCV-positive patients were found to have a high risk of variceal bleeding because they had large varices (grade III-IV) or small varices with red signs. In these HCV-related cirrhotic patients, the 14 patients with Child-Pugh class A were categorized as the HCV-related compensated cirrhotic patients with a high risk of variceal hemorrhage (high-risk varices group).

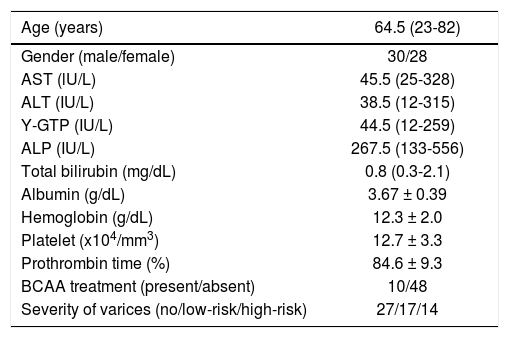

The characteristics of all 58 compensated cirrhotic patients (27 patients in the no varices group, 17 patents in the low-risk varices group, and 14 patients in the high-risk varices group) are shown in table 2. The population consisted of 30 males (52%) and 28 females (48%), and the age of patients ranged from 23 to 82 years old (median 64.5). BCAA were administrated to none of the 27 patients (0%) in the no varices group, 5 of 17 patients (29%) in the low-risk varices group, and 5 of 14 (36%) patients in the high-risk varices group.

Characteristics of the total 58 patients with HCV-positive compensated cirrhosis.

| Age (years) | 64.5 (23-82) |

|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 30/28 |

| AST (lU/L) | 45.5 (25-328) |

| ALT (IU/L) | 38.5 (12-315) |

| Y-GTP (IU/L) | 44.5 (12-259) |

| ALP (IU/L) | 267.5 (133-556) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.8 (0.3-2.1) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.67 ± 0.39 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.3 ± 2.0 |

| Platelet (x104/mm3) | 12.7 ± 3.3 |

| Prothrombin time (%) | 84.6 ± 9.3 |

| BCAA treatment (present/absent) | 10/48 |

| Severity of varices (no/low-risk/high-risk) | 27/17/14 |

BCAA: branched-chain amino acids. BTR: BCAA to tyrosine ratio. Quantitative variables were expressed as the mean values ± SD or median (range).

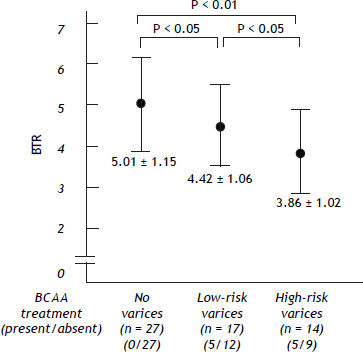

Irrespective of the higher ratio of BCAA-treated patients, the values of the BTR were decreased as the bleeding risk increased, suggesting that the low BTR value was correlated with the severity of portal hypertension (Figure 3).

The values of the branched-chain amino acids to Tyr ratio (BTR) in patients with HCV-related compensated (Child-Pugh class A) cirrhosis. The BTR values were reciprocally decreased as the bleeding risk of esophageal varices increased. There was a significant difference between the no varices group vs. the low-risk varices group, the no varices group vs. the high-risk varices group and the low-risk varices group vs. the high-risk varices group.

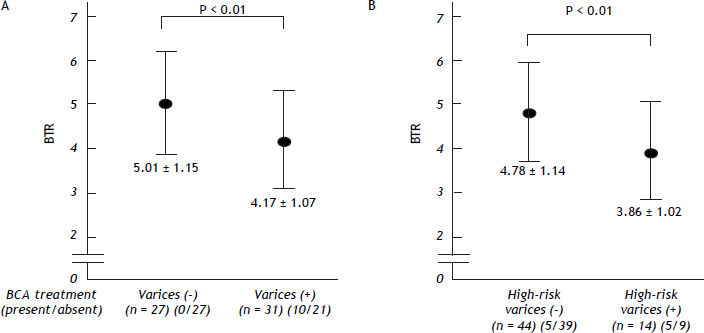

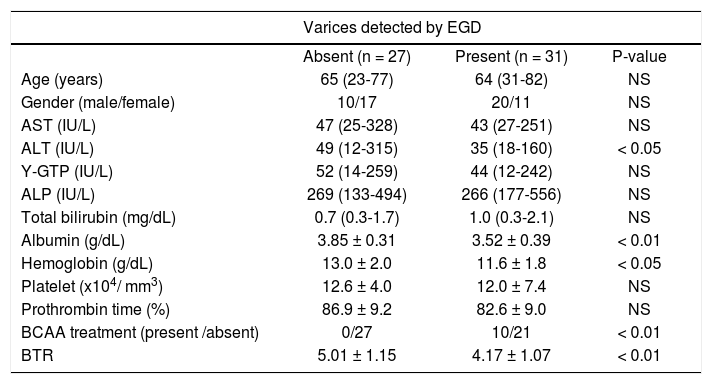

We also examined the differences in the BTR values between the patients with varices and patients without varices. Comparing the 31 patients with varices (the high-risk varices group and the low-risk varices group) and 27 patients without varices (the no varices group), the BTR value was significantly lower in patients with varices than that in patients without varices, although the percentage of BCAA-treated patients was significantly higher in the group with varices than in the patients without varices, suggesting that the decreased BTR values was associated with the presence of varices (Figure 4A). The low BTR value was found to be significantly different in the presence of varices, as well as a higher ALT value and lower albumin and hemoglobin values (Table 3).

The decreased values of the branched-chain amino acids to Tyr ratio (BTR) in relation to the severity of varices in patients with HCV-related compensated (Child-Pugh class A) cirrhosis. A. The branched-chain amino acids to Tyr ratio (BTR) in patients with HCV-related compensated (Child-Pugh class A) cirrhosis with or without varices. A comparison between the 31 patients with varices (in the high-risk varices group or the low-risk varices group) and the 27 patients in the no varices group is shown. The BTR value was significantly lower in the patients with varices than that in the patients without varices. B. The branched-chain amino acids to Tyr ratio (BTR) in patients with HCV-related compensated (Child-Pugh class A) cirrhosis with or without high-risk varices. A comparison between the 14 patients in the high-risk varices group and the 35 patients without high-risk varices (in either the no varices group or the low-risk varices group) is shown. The BTR ratio was significantly lower in patients with high-risk varices than that in patients without high-risk varices.

Characteristics of the compensated cirrhotic patients with or without varices.

| Varices detected by EGD | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Absent (n = 27) | Present (n = 31) | P-value | |

| Age (years) | 65 (23-77) | 64 (31-82) | NS |

| Gender (male/female) | 10/17 | 20/11 | NS |

| AST (IU/L) | 47 (25-328) | 43 (27-251) | NS |

| ALT (IU/L) | 49 (12-315) | 35 (18-160) | < 0.05 |

| Y-GTP (IU/L) | 52 (14-259) | 44 (12-242) | NS |

| ALP (IU/L) | 269 (133-494) | 266 (177-556) | NS |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.7 (0.3-1.7) | 1.0 (0.3-2.1) | NS |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.85 ± 0.31 | 3.52 ± 0.39 | < 0.01 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.0 ± 2.0 | 11.6 ± 1.8 | < 0.05 |

| Platelet (x104/ mm3) | 12.6 ± 4.0 | 12.0 ± 7.4 | NS |

| Prothrombin time (%) | 86.9 ± 9.2 | 82.6 ± 9.0 | NS |

| BCAA treatment (present /absent) | 0/27 | 10/21 | < 0.01 |

| BTR | 5.01 ± 1.15 | 4.17 ± 1.07 | < 0.01 |

BCAA: branched-chain amino acids. BTR: BCAA to tyrosine ratio. Quantitative variables were expressed as the mean values ± SD or median (range).

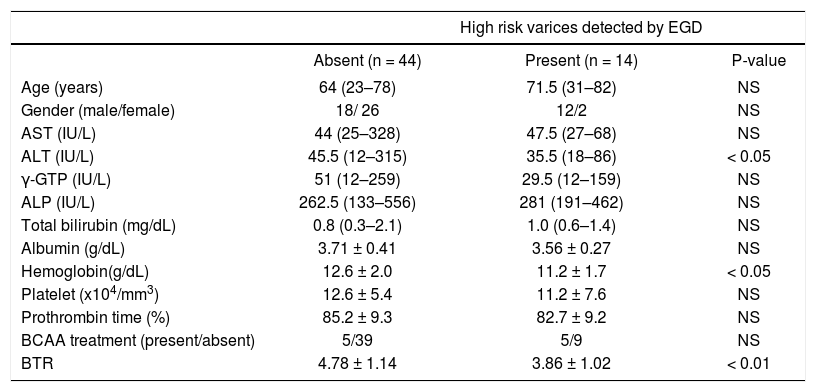

When we compared the 14 patients in the high-risk varices group with the 44 patients in the no varices group or the low-risk varices group, the BTR value was significantly lower in the patients in the high-risk varices group, although the percentage of BCAA-treated patients was higher in the patients with high-risk varices than in patients without high-risk varices (Figure 4B), thus suggesting that a low BTR value is related to an increased risk of variceal hemorrhage. We also found a significantly higher ALT and lower hemoglobin level in the high-risk varices group. Interestingly, the BTR value showed the smallest p-value (P = 0.0093 < 0.01) among all of the parameters examined (Table 4).

Characteristics of the compensated cirrhotic patients with or without high-risk varices.

| High risk varices detected by EGD | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Absent (n = 44) | Present (n = 14) | P-value | |

| Age (years) | 64 (23–78) | 71.5 (31–82) | NS |

| Gender (male/female) | 18/ 26 | 12/2 | NS |

| AST (IU/L) | 44 (25–328) | 47.5 (27–68) | NS |

| ALT (IU/L) | 45.5 (12–315) | 35.5 (18–86) | < 0.05 |

| γ-GTP (IU/L) | 51 (12–259) | 29.5 (12–159) | NS |

| ALP (IU/L) | 262.5 (133–556) | 281 (191–462) | NS |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.8 (0.3–2.1) | 1.0 (0.6–1.4) | NS |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.71 ± 0.41 | 3.56 ± 0.27 | NS |

| Hemoglobin(g/dL) | 12.6 ± 2.0 | 11.2 ± 1.7 | < 0.05 |

| Platelet (x104/mm3) | 12.6 ± 5.4 | 11.2 ± 7.6 | NS |

| Prothrombin time (%) | 85.2 ± 9.3 | 82.7 ± 9.2 | NS |

| BCAA treatment (present/absent) | 5/39 | 5/9 | NS |

| BTR | 4.78 ± 1.14 | 3.86 ± 1.02 | < 0.01 |

BCAA: branched-chain amino acids. BTR: BCAA to tyrosine ratio. Quantitative variables were expressed as the mean values ± SD or median (range).

EGD is the most reliable method to determine whether a cirrhotic patient should receive a prophylactic treatment for variceal hemorrhage.2,3 However, patients with a well-maintained liver function (Child-Pugh class A) usually do not have any clinical symptoms, sometimes leading to a negative attitude toward undergoing the EGD examination. Therefore, it should be attractive to find a biomarker which is related to the presence and the bleeding risk of varices even in compensated (asymptomatic) cirrhotic patients.

Although several biomarkers of liver fibrosis have been reported to predict the presence of varices,4–6 there have been few studies that have investigated the relationships between the endoscopic variceal findings and the fibrosis-related markers in compensated cirrhotic patients with well-maintained liver function (Child-Pugh class A status). In particular, there have been few studies that have investigated the relationship between the metabolic parameters and the severity of varices in compensated cirrhotic patients.

We previously examined several biomarkers, including the AST-to-ALT ratio (AAR),14 the FIB-4 indices15 and the AST-to-platelet count ratio index (APRI)16 in HCV-related cirrhotic patients with Child-Pugh class A status, and reported that the AAR was associated with both with presence and the bleeding risk of varices.17 In addition, we examined the two glycated proteins (glycated albumin: GA and glycated hemoglobin: HbA1c) proteins in patients with CLD, and reported that the GA/HbA1c ratio was correlated with the severity of the esophageal varices in HCV-related cirrhotic patients.18 We also reported that this ratio (the GA/HbA1c ratio) was increased with the progression of liver fibrosis in patients with HCV-related CLD and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.19,20

In the present study, we focused on the amino acid imbalance in CLD and found the BTR to be decreased with the severity of varices. Amino acid imbalances are well-known metabolic disorders in patients with CLD, and a previous report examined the relationship between the progression of liver fibrosis and the BTR value in CLD patients with various etiologies, including HCV infection, HBV infection, autoimmune hepatitis and cryptogenic hepatitis.21 Furthermore, Habu, et al.22 showed that there was an association between a low BTR value and the presence of a porto-systemic shunt in patients with compensated liver cirrhosis. We herein showed that the value of BTR decreased with the progression of liver fibrosis and with the severity of varices in HCV-related CLD patients, and these results were in agreement with previous reports regarding CLD patients with various etiologies.21,22 Interestingly, despite the fact that the ratio of BCAA-treated patients was increased with the severity of varices, the BTR value was inversely decreased with the severity. Therefore, if none of the patients had received the BCAA treatment, the decrease of the BTR value with the progression of liver fibrosis and the severity of varices would have been even more remarkable. Our findings suggest that the BTR value is a unique parameter that is strongly associated with various clinical conditions in patients with HCV-positive CLD, including the degree of liver fibrosis and the severity of varices, as well as the amino acid imbalance. It is interesting to note that recent reports.23,24 suggest that the values of BTR are associated with the prognosis of HCC. Although the main focus of the disorders of amino acid metabolism has been on patients with cirrhosis, an evaluation of the amino acid imbalance by measuring the BTR should provide new information with regard to the various clinical statuses in patients with CLD, as well as in cirrhotic patients.

It is of interest to clinicians to determine cut-off values of the BTR that can discriminate between compensated cirrhotic patients with or without varices and with or without high-risk varices. We performed the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses and obtained possible cut-off values (BTR values of 4.39 and 3.93, respectively). However, it was not easy to identify the cut-off values of the BTR that had a sufficient diagnostic performance, perhaps because of the relatively small number of patients in the present study. Therefore, further investigations in a larger number of patients are needed.

In summary, we showed that the BTR value is associated with the progression of liver fibrosis and the severity of esophageal varices. The liver plays an important role in many aspects of metabolism, and various metabolic disorders involving glucose, amino acids and lipids are observed in patients with CLD.25,26 Therefore, it would be interesting and important to investigate the metabolic parameters, including the GA/ HbA1c ratio and the BTR value, for their correlations with the presence of varices or the bleeding risk of varices in a larger number of patients.

Abbreviations- •

AAA: aromatic amino acids.

- •

BCAA: branched-chain amino acids.

- •

BTR: BCAA to Tyr ratio.

- •

CLD: chronic liver disease.

- •

EGD: esophagogastroduodenoscopy.

Supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Health and Labor Sciences Research from the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan.