Suicide is one of the world's greatest public health problems. More than 700,000 people lose their lives to suicide every year. While funding for mental health waits to be increased, thousands of suicides occur every day.

Material and methodsThis study aims to quantify the global impact of suicide compared to other external causes of death in terms of years of potential life lost (YPLL), and how this will change between 1995 and 2020. Our source of information is the World Health Organization (WHO) mortality database. We then use YPLL, a standard measure of premature mortality and burden of disease that brings precision to the assessment of the impact of different causes of death. This, combined with the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) as a way of expressing increase, gives us a better understanding of the real situation and trends of suicide compared to other external causes of death in different countries worldwide.

ResultsBased on the available sources of information and the selection criteria, we obtained a sample of 69 countries. The CAGR for all causes per capita decreased over the observed period in 65 countries, and it increases in 4 countries. In contrast, the CAGR specifically for suicide decreased in 49 countries, while an increase was observed in 20 countries.

ConclusionsPrevention of most external causes of mortality shows promising data in most countries. However, this is not the case for suicide. Thus, YPLL due to suicide have decreased to a comparatively lesser extent and have even increased in some countries, a very worrying situation that poses many clinical and epidemiological challenges.

Suicide is one of the world's greatest public health problems. Each year, more people die from suicide than from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), malaria, breast cancer, war, or homicide. In 2019, one in 100 deaths will be the result of suicide.1

While mental health funding waits to be increased, thousands of suicides occur every day. Although mental illness is a major health problem, the resources devoted to it are, in most cases, inadequate. As described in the editorial “If depression were cancer” published in Nature,2 tackling this problem requires global government and community action, including funding, awareness raising and risk assessment.3 The economic costs of suicide are also striking. Studies such as Chen et al.4 suggest that the cost of suicide in Japan in 2006 was approximately $197 million. There is another indicator that may be more important than economic impact or the number of deaths: years of potential life lost (YPLL), a standard measure of premature mortality and disease burden that provides precision in assessing the impact of different causes of death. Its values increase when the causes studied affect the younger population, and it allows us to assess the impact of deaths on society.

In mental health, the YPLL health indicator has been used to draw attention to the impact of various conditions and serious diseases such as cancer,5 infectious diseases6 or schizophrenia,7 where they reflect mortality trends in younger age groups and provide a more accurate overview of premature mortality as well as secondary productivity loss.

However, studies exploring YPLL due to suicide are less common. Among this last group, we find the works of Porras-Segovia et al.8 and Merayo-Cano et al.,9 which compared YPLL due to suicide with those due to COVID-19 in the USA and Spain, respectively. Porras-Segovia et al.8 found that although YPLL as a consequence of suicide were almost as high as those produced by COVID, comparatively the measures taken for suicide control are strikingly lower. For their part, Merayo-Cano et al.9 found that YPLLs were higher for suicide than for COVID-19 in Spain.

Other previous studies have analyzed external mortality rates and compared them in different countries. For instance, Bourbeau10 compared mortality rates from violence with other external causes of death in a large number of countries, finding differences in the causes and structure of mortality rates according to the socio-economic level of the country. Other works such as Bouvier-colle et al.11 have also compared external causes of death. They found a marked increase in mortality at younger ages. They concluded that suicide had increased in all countries while mortality from road traffic accidents had decreased in many of them.

However, no previous study has analyzed the status of suicide compared to other external causes of death in different countries around the world. This study aims to quantify the global impact of suicide compared to other external causes of death, and its evolution over the last three decades. We hypothesize that while YPLL due to all other external causes of mortality will have decreased considerably over the years in most countries, YPLL due to suicide will have experienced no such reduction or even increased in some countries.

MethodsDesign and sources of informationThis is an epidemiological data review study. We followed the Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting (GATHER).12 Our source of information was the World Health Organization (WHO) mortality database, which presents a compilation of mortality data by age, sex and cause of death, as reported annually by Member States from their civil registration systems (WHO Mortality Database).

Our inclusion criteria were:

- •

Countries that had published censuses of mortality from all causes, violence, suicide, war, and accidents for ages 0–75 years in the WHO Mortality Database in April 2023.

- •

Where data were presented by age group.

- •

With data available from 1995 to 2020.

Exclusion criteria were:

- •

Those countries which had 5 years or more with missing data in the referred period (1995–2020).

- •

Countries with less than 1,000,000 inhabitants according to the Data World Bank.13

- •

We have also categorised the socio-economic level of the countries we are referring to according to the Data World Bank.14

In this study, we used years of potential life lost (YPLL) as an indicator instead of the usual mortality rates because the number of deaths does not provide information about premature death and its social, economic and health consequences. The calculation of YPLLs can be used to detect causes of death that change rapidly, even if the level of mortality is relatively low.15

In addition we also considered the compound annual growth rate (CAGR), raw and adjusted per capita. The CAGR is a way of expressing the growth of a specific indicator, in our case YPLL, with respect to the level of previous years. To calculate it, the final value of the asset is divided by the initial value, and the result is raised to the power of one by the number of years. Finally, subtract one from the result.

We decided to add the values adjusted by 1,000,000 inhabitants in order to be able to reliably compare situations between countries with different populations.

Statistical analysesThe calculation of YPLL before age 75 was performed for each cause, country, and year. We chose a standard of YPLL before age 75 because is closer to global life expectancy, which is 73.4 years in 2019 according to the WHO.16

To calculate YPLL before age 75, we first look at the number of deaths in each age group according to the WHO Mortality Database. We then subtracted the average age of each age group from the age of 75. We multiplied the result by the number of deaths corresponding to each age group. Finally, we added the results to obtain the total YPLL.

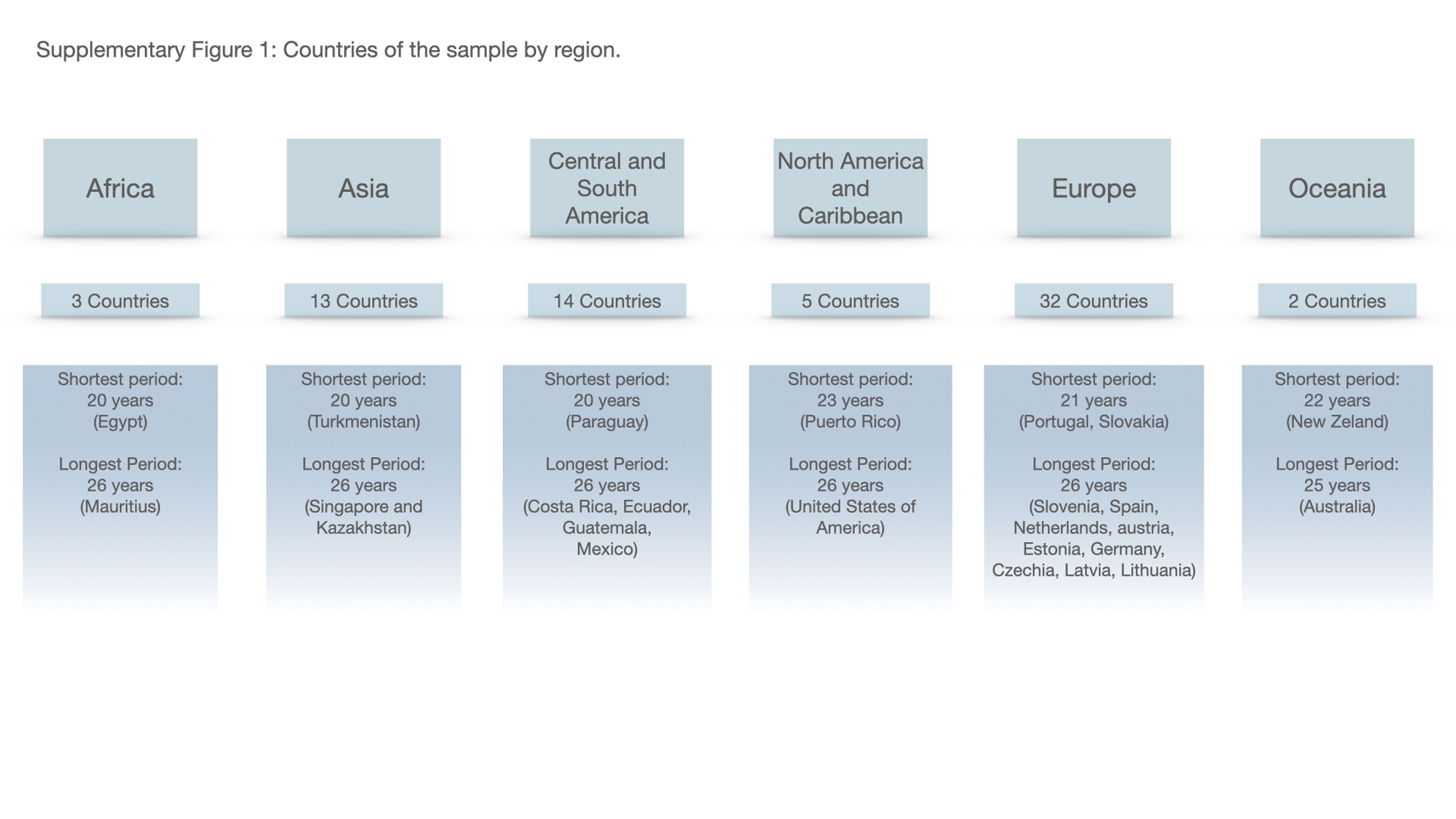

ResultsBased on the available sources of information and the selection criteria, we obtained a sample of 69 countries. Of these, 3 countries belonged to the African continent, 13 to Asia, 14 to Central and South America, 32 countries corresponded to the European continent, 5 countries belonged to North America and 2 to Oceania.

The complete list of countries is shown in supplementary Table 1.

The longest observation period was 26 full years, between 1995 and 2020, in the following countries: Slovenia, Guatemala, Singapore, Spain, Netherlands, Austria, Estonia, Mauritius, USA, Germany, Ecuador, Czechia, Latvia, Costa Rica, Kazakhstan, Lithuania and Mexico.

The shortest period was 20 years in the following countries: Turkmenistan, Egypt and Paraguay.

The mean number of years of observation was 24.2 years.

supplementary Fig. 1 shows the outline of the countries included.

Worldwide resultsThe mean YPLL per capita per year for all external causes ranged from 6292 in Singapore to 64,695 for Russia. The mean YPLL per capita per year for suicide ranged from 35 for Egypt to 9743 for Lithuania..

As for the CAGR for all causes per capita, we observed a decrease over the observed period in 65 countries. The largest decrease was observed in Estonia, with a CAGR of −3.9%. In contrast, an increase was observed in 4 countries. The largest increase was observed in the Dominican Republic with 1.0%.

Considering only the CAGR for suicide per capita, a decrease was found in 49 countries over the period studied. The largest decrease was observed in El Salvador with −5.9%. On the other hand, an increase was observed in 20 countries, with Dominican Republic leading with 5.6%.

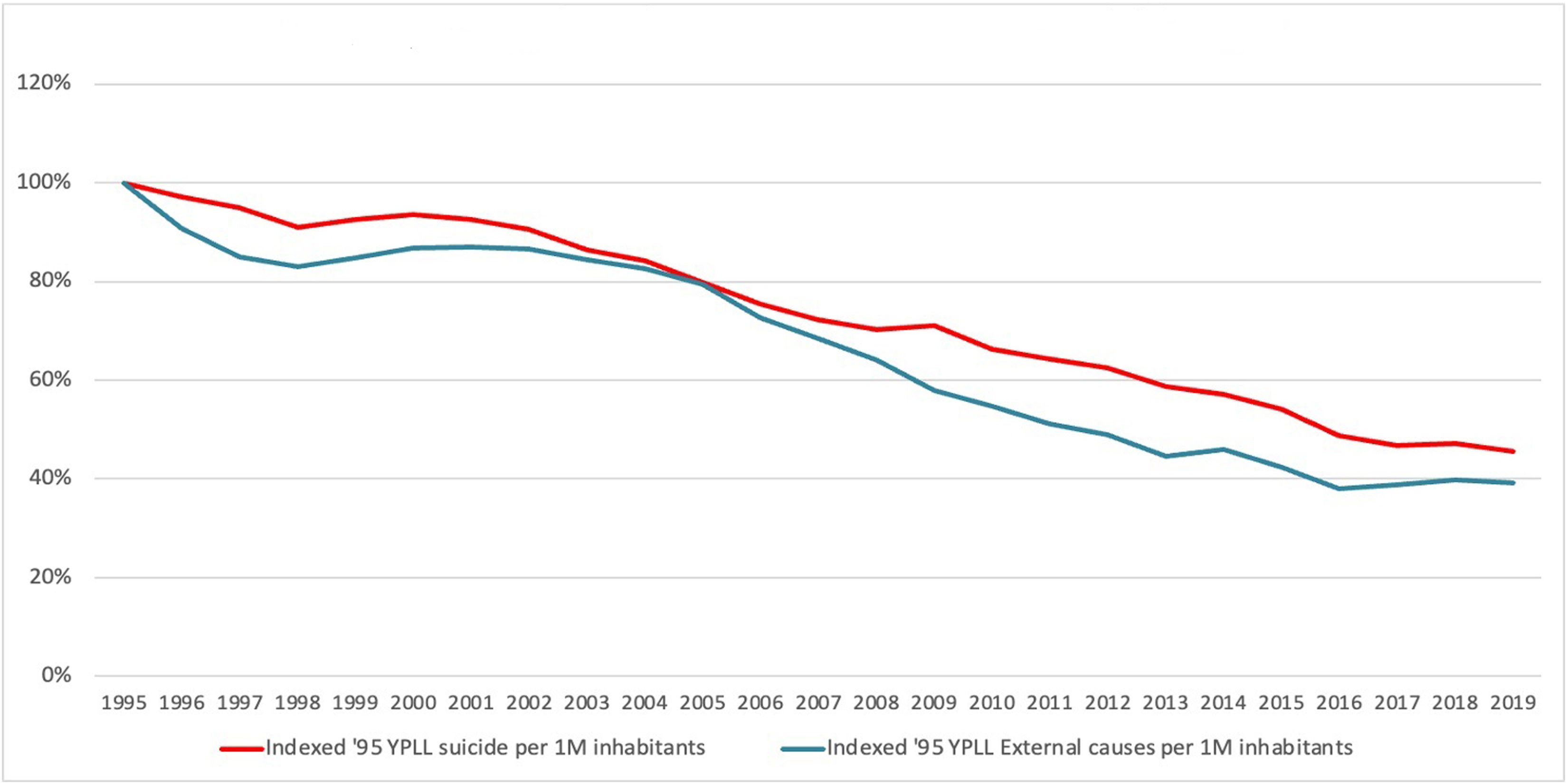

AsiaIn Asia, the percentage of suicide YPLL to total YPLL ranges from 0.5% in 2009, 2014, 2017 and 2019 in Armenia to 17.5% in 2019 in Korea, while the total CAGR ranges from −2.7% in Korea to 1.8% in Kuwait. The CAGR for suicide ranges from −6.1% in Armenia to 4.7% in Kuwait.

Of the 13 countries analyzed, in 12 of them, YPLL due to suicide exceeded YPLL due to violence.

In the case of the CAGR for suicide, an increase was observed in 4 of the 13 countries analyzed. While in deaths due to injuries and violence there was a CAGR decrease in 100% of the countries analyzed (with the exception of Georgia in the case of violence, where there was a significant increase).

When analyzing the data detailed, it is observed that Japan has one of the highest percentages of YPLL as a result of suicide among all causes, 11.9%. In the period from 1995 to 2019, YPLL due to accidents and violence have decreased significantly (CAGR of −2.8% and −4.8% respectively), while YPLL due to suicide have decreased comparatively more modestly (−0.4%).

A similar pattern was observed in Korea, with one of the highest percentages of YPLL due to suicide (11.3%). It is noteworthy that the other causes (injuries and violence) have decreased (CAGR of −3.7% and −4.4% respectively) while suicide has increased (+2.2%) in the period from 1995 to 2019.

Hong Kong, also has a high percentage of YPLL as a result of suicide, 9.5%. Moreover, the CAGR related to suicide is the only one that increases in the period from 1995 to 2017, while all other violent causes decrease.

When we consider the per capita adjustments, Kuwait is remarkable, where an increasing CAGR is observed, which decreases strikingly if this adjustment is made, from 4.7% to 0.5%.

North America and the CaribbeanMean global YPLL causes per capita range from 42,071 in 2019 in Canada to 109,167 in 1995 in Puerto Rico.

Mean YPLL suicide per capita ranged from 490 in 1996 in Dominican Republic to 5541 in 1995 in Cuba.

As for the percentage of YPLL of suicide with respect to all causes, it ranged from 0.7% in 1997 and 2002 in the Dominican Republic to 8.6% in 1999 in Canada.

Total CAGR ranged from −2.7% in Puerto Rico to 2.3% in the Dominican Republic.

Suicide CAGR ranged from −3.5% in Cuba to 7.0% in the Dominican Republic.

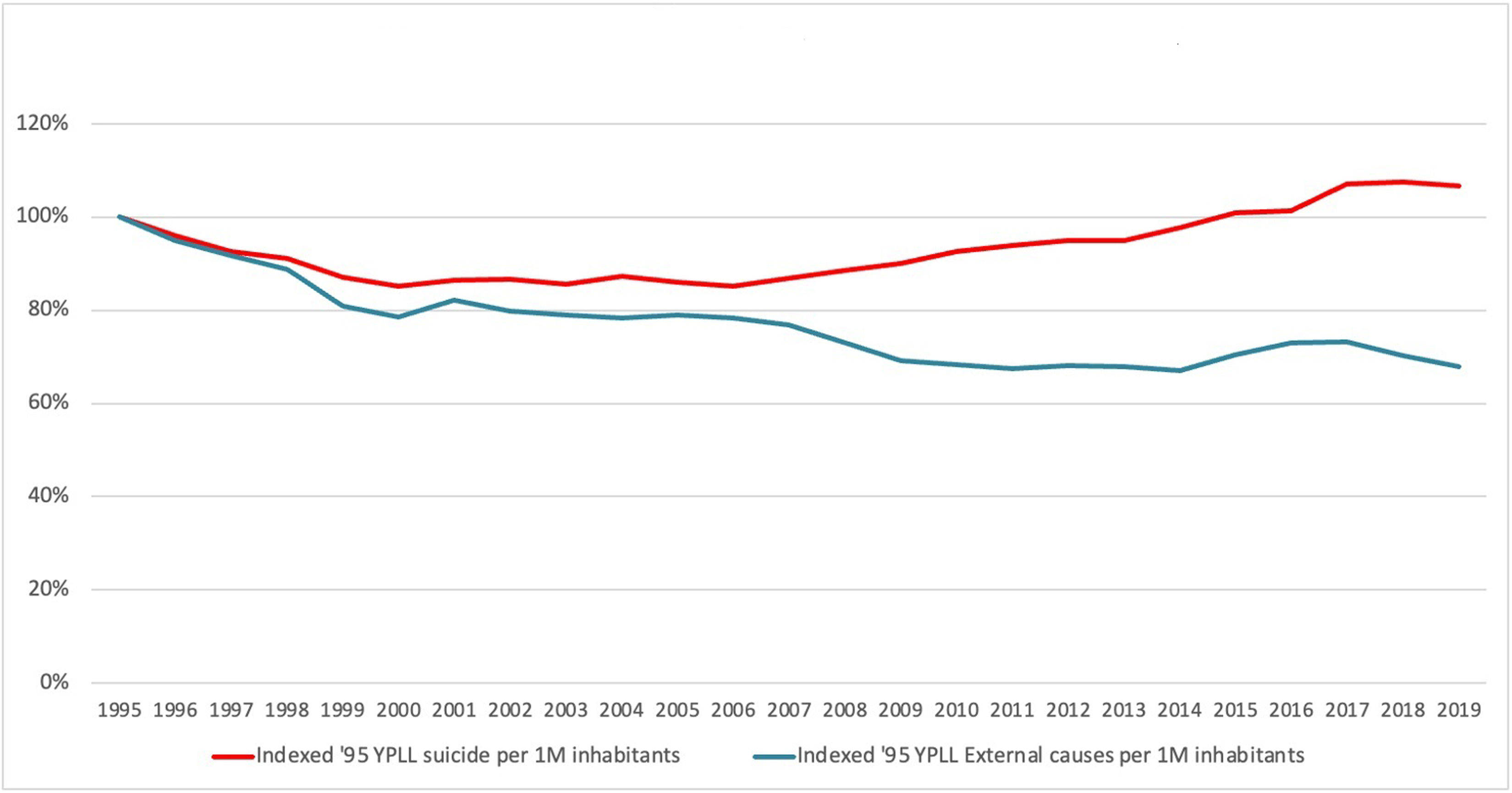

Of the 5 countries analyzed, in 3 of them YPLL due to suicide exceeded YPLL due to violence.

In the case of the CAGR for suicide, an increase was observed in 2 of the 5 countries analyzed. Meanwhile, deaths due to injury and violence showed a decrease in the CAGR in all countries except one.

Canada stands out, with one of the highest percentages of YPLL as a result of suicide, 7.5%. This accounts for 26.8% of YPLL due to external causes in the period 1995–2019.

In the USA, while other external causes of death have kept stable in the period 1995–2020, the CAGR rate related to suicide has increased (CAGR of 1.3%).

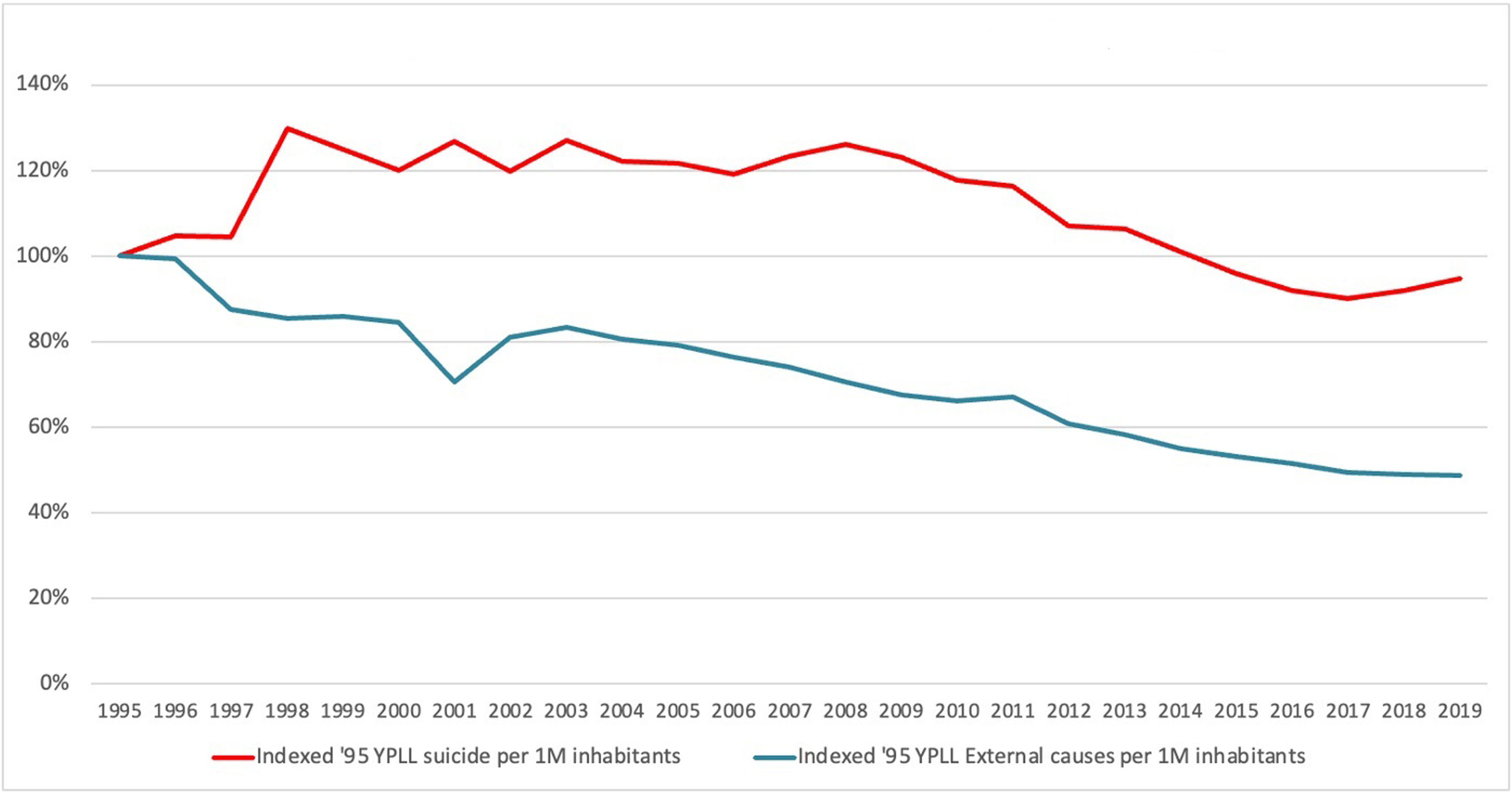

EuropeMean YPLL for all causes per capita ranges from 30,736 in 2018 in Switzerland to 239,538 in 1995 in Rep. of Moldova.

Mean YPLL suicide per capita ranges from 686 in 2002 in Greece to 13,465 in 1996 in Lithuania.

As for the percentage of suicide YPLL with respect to the total, it ranges from 0.0% in 2005, 2006 and 2009 in Albania to 12.3% in 1995 in Finland.

Total CAGR ranges from −4.2% in Estonia to −0.9% in North Macedonia.

CAGR suicide ranges from −5.6% in Russia to 0.9% in United Kingdom.

In 100% of the 32 countries analyzed, YPLL due to suicide exceeded YPLL due to violence.

Although we only found an increase in the CAGR related to suicide in 2 of the 32 countries analyzed, it is noteworthy that in 81.25% of them suicide is the cause of external death that has improved the least over this period.

The case of Finland stands out. When a detailed analysis is performed, in spite of finding a decreasing CAGR index related to suicide (−2.9%), it is another of the countries with the highest percentage of YPLL as a result of suicide among all causes of death, with 10.0% in the period from 1995 to 2019. It is also one of the countries with the highest YPLL per capita as a result of suicide with a total of 5379 YPLL, on the other hand it also accounts for a high percentage of YPLL among external causes of death, 30.21%.

Other leading countries are Slovenia with 9% YPLL as a result of suicide and Lithuania with 8.8%.

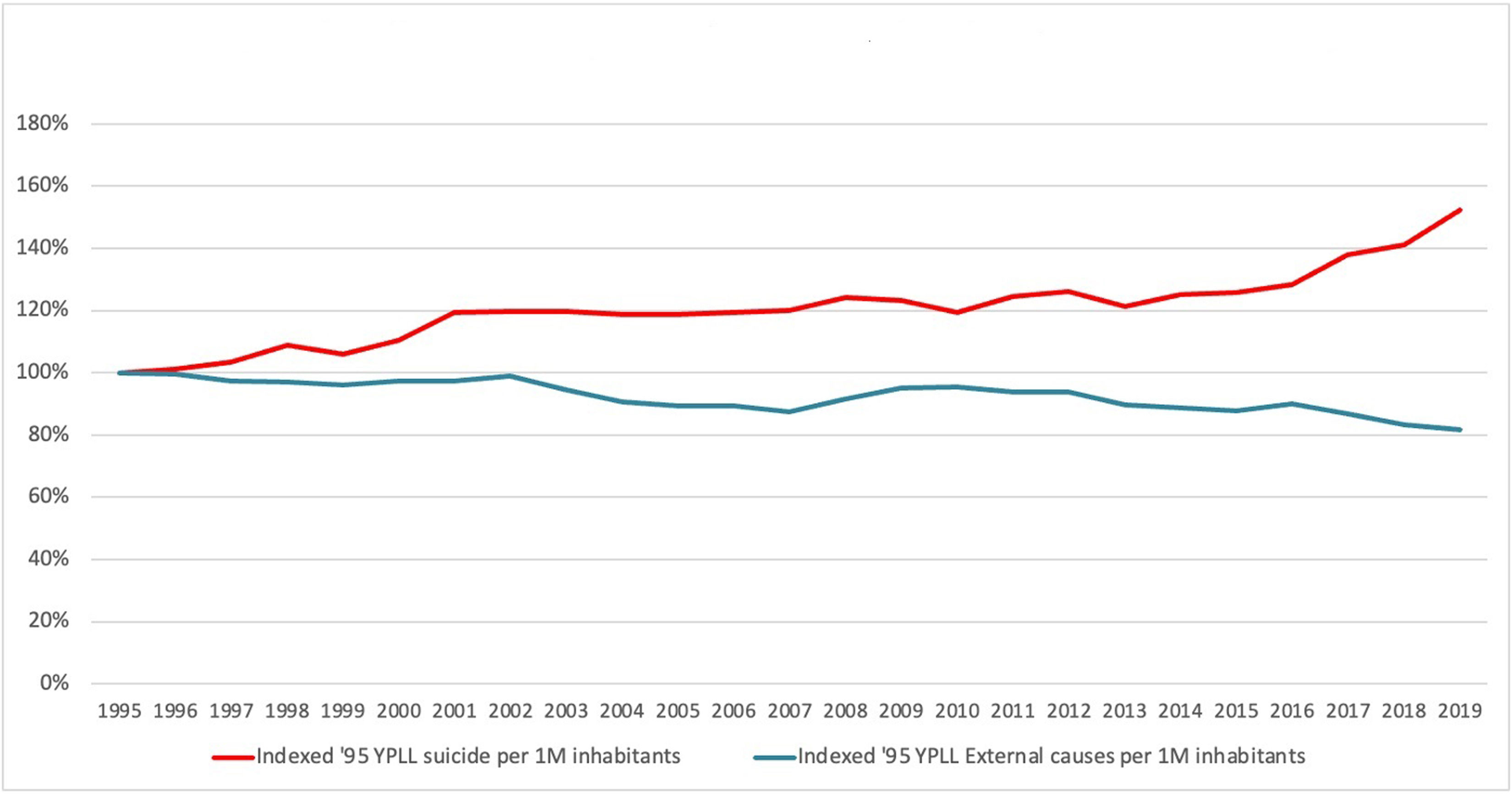

Central and South AmericaMean YPLL for all causes per capita ranges from 44,221 in 2016 in Peru to 248,228 in 1995 in Guatemala. Mean YPLL suicide per capita ranges from 216 in 2009 in Peru to 5816 in 2019 in Uruguay. As for the percentage of suicide YPLL with respect to the total, it ranges from 0.3% in various years such as 2000 in Guatemala to 8.5% in 2017 in Uruguay.

Regarding the CAGR, the total figure ranges from −1.4% in Guatemala to 2.2% in Venezuela. CAGR suicide ranges from −5.6% in El Salvador to 6.3% in Paraguay.

Argentina maintains an increase in the CAGR of 2.7% of YPLL as a result of suicide. It has gone from 1.7% YPLL as a result of suicide in 1995 to 3.95% in 2019. It has grown the most compared to the other causes analyzed (CAGR of 0.5% for violence and CAGR of −0.3% for accidents).

Of the 14 countries analyzed, in 3 of them YPLL due to suicide have exceeded those caused by violence.

If we analyze the CAGR, there is an improvement trend in injuries and violence (92.9% in both and 57.1% in both), while we find an increase in deaths due to suicide in 11 of the 14 countries analyzed.

In the case of Mexico, although there is an increase in YPLL for all the causes analyzed, the CAGR for suicide is strikingly increasing at 4.0%. In 1995, YPLL secondary to suicide accounted for 1.12% of all-cause YPLL, whereas in 2020 it has doubled.

Colombia is another striking case. While trends for accidents and violence have declined, YPLL secondary to suicide have increased considerably with a CAGR of 3.6%.

OceaniaMean YPLL for all causes per capita ranges from 33,539 in 2020 in Australia to 64,372 in 1995 in New Zealand. Mean YPLL suicide per capita ranged from 3136 in 2006 in Australia to 5589 in 1997 in New Zealand. As for the percentage of suicide YPLL relative to the total, this ranges from 7.6% in 1995 in Australia to 11.4% in 2017 also in Australia.

Total CAGR ranges from −1.0% in New Zealand to −0.5% in Australia. CAGR suicide ranges from −0.3% in New Zealand to 1.0% in Australia. YPLLs are higher for suicide than for violence in the two countries analyzed. In Australia the CAGR for suicide has improved much less significantly than the other external causes of death.

AfricaData from three African countries are available. In the case of Egypt, there was a 2.1% increase in the CAGR for suicide, which remained stable when adjusted for per capita, with a CAGR of 0.0%.

In the case of South Africa, the largest increase was observed for violence, followed by suicide, while the number of injuries decreased.

In Mauritius, the CAGR for suicide decreased, but by a smaller percentage than for injuries. Violence, on the other hand, showed an increase. Mauritius is the country with the highest percentage of YPLL due to suicide among the other causes of death.

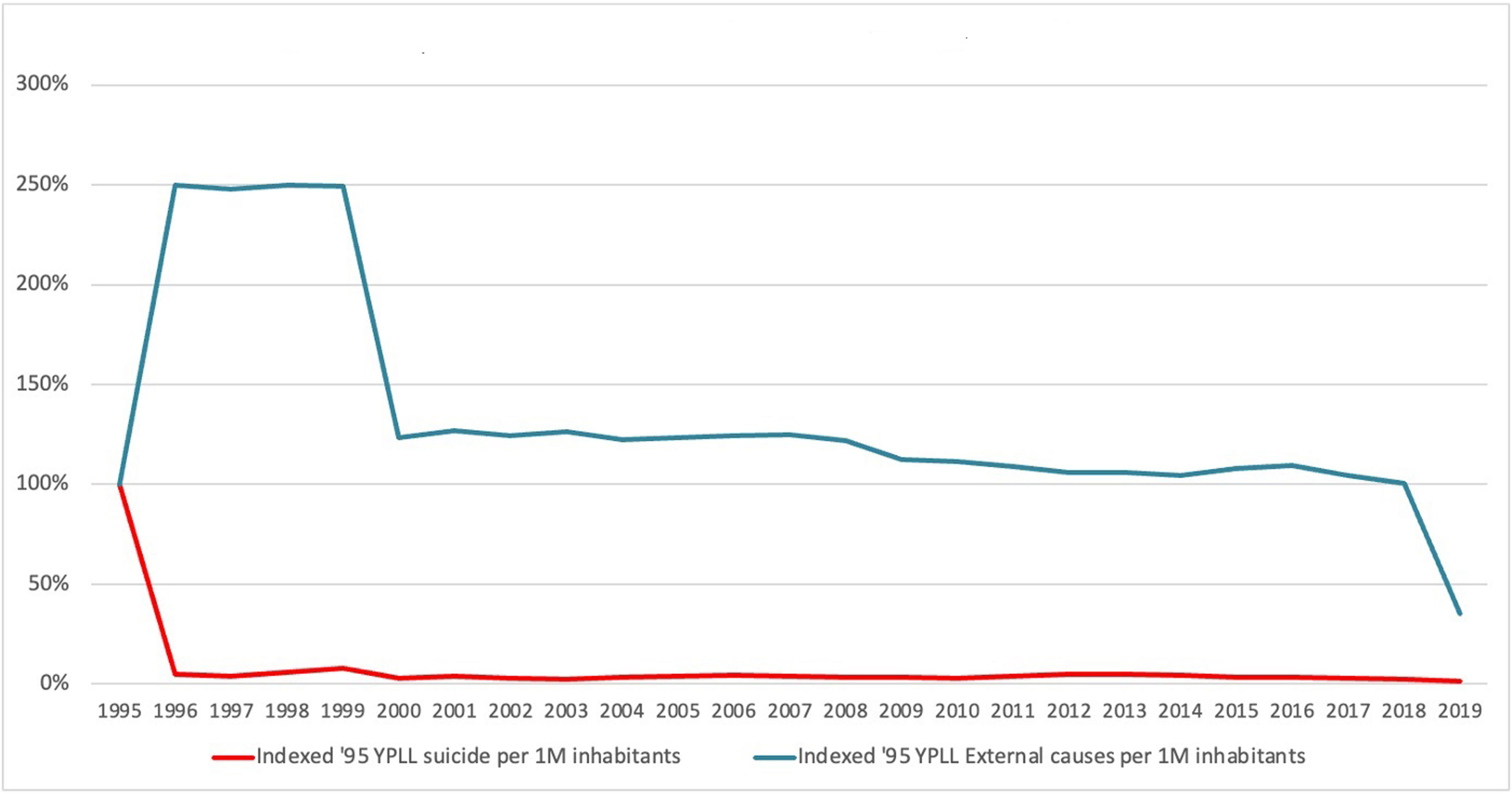

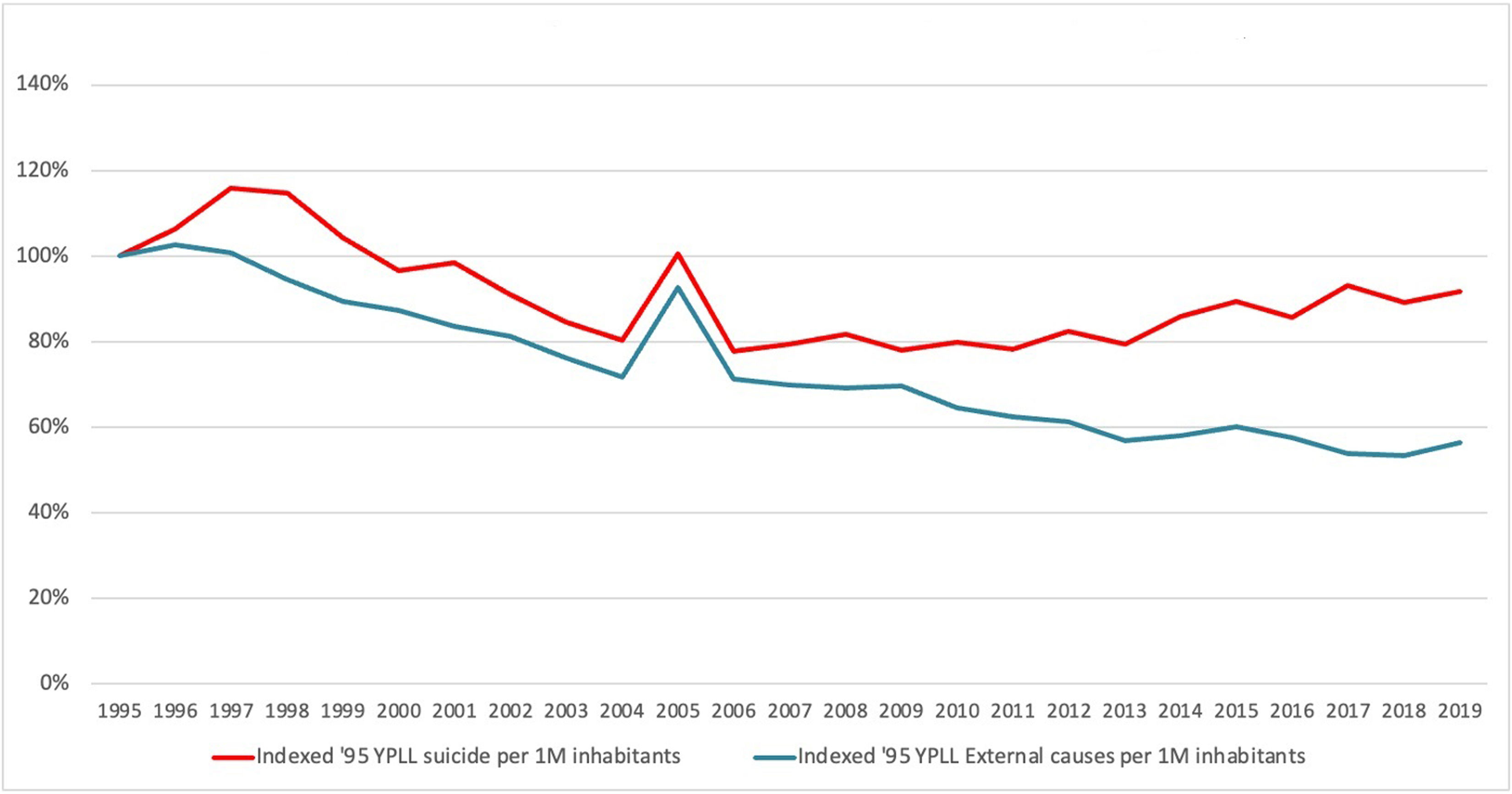

We include the graphs by region showing suicide and other external causes of death indexed for better understanding and visualization of the results described above. We have chosen to adjust the data to a common reference point to facilitate relative comparisons (Figs. 1–6).

In our study, we explored the comparative YPLL data for suicide, violence, and injuries in several countries worldwide. We found that the mean YPLL per capita per year for all external causes ranged from 6292 to 64,695 while the mean YPLL per capita per year for suicide ranged from 35 to 9743. We found that the CAGR for all causes per capita decreased over the observed period in 65 countries, and it increases in 4 countries. In contrast, the CAGR specifically for suicide decreased in 49 countries, while an increase was observed in 20 countries.

Thus, our initial hypothesis that while YPLL due to all other external causes of mortality will have decreased considerably over the years in most countries, YPLL due to suicide will have experienced no such reduction or even increased in some countries, has been confirmed.

Below we discuss some of the possible mechanisms that could explain our findings.

Comparison to previous studiesIn comparison with previous studies, we have also found that the epidemiological situation related to suicide is worrying. Thus, Porras-Segovia et al.,8 in their comparison of the YPLL of suicide and COVID, found that both had very similar scores. In our study, instead of comparing with natural causes of mortality, we have explored the impact of suicide in comparison with other external causes. As with the natural causes explored in previous studies, it can be seen that the impact of suicide considerably exceeds the usual public health consideration. Thus, in Spain, it is estimated that the Directorate General of Traffic – the body in charge of organising state campaigns for the prevention of motor vehicle accidents – consumes almost 25% of the Spanish state's institutional advertising budget, a figure much higher than that received by suicide prevention campaigns.17

Socio-economic factorsIn our study, we found that the fastest growing suicide CAGRs were found in countries corresponding to low- and middle-income countries. However, we found that the highest percentages of YPLL due to suicide over all other external causes of death occurred in high-income countries, such as Japan, Korea, Finland, Australia or Canada.

According to our analysis, we believe that we need to take into account not only the socio-economic position of the population, but also sudden changes in it, such as the situation experienced in Western countries after the 2008 crisis, unemployment or overwork, which require its maintenance or improvement. Situations such as increased unemployment rates, social fragmentation, low socio-economic status, and low levels of education are significantly associated with increased suicide rates.18–21 For instance, Koo and Cox19 explored the relationship between the suicide rate and the unemployment rate found it significantly and robustly positive even after controlling for several social variables. For their part, Yoshioka et al.,21 in their study about association between characteristics of population and suicide found that the level of urbanicity, fragmented municipalities or area-specific socio-economic characteristics were related with the risk of suicide.

Geographic and demographic factorsThe analysis of the results in countries such as Canada or Australia, for example, can relate the suicide situation to possible geographical and urban factors. Compared with people living in urban areas, people living in rural areas who died by suicide were younger, more likely to have used firearms or hanged themselves, and had a higher average blood alcohol content at the time of death. Rural and agricultural populations were also less likely to have a history of suicide attempts, mental illness or alcohol abuse, and to have fewer specialists and less access to mental health care.22–24

In the case of Canada and the United States, racial discrimination against minorities, particularly black, Latino, and indigenous populations, may be associated with increased problems with alcohol use.25,26

Another possible common denominator and risk factor that may contribute to higher suicide rates is sunlight. Several studies have shown how insufficient sunlight exposure increases the number of deaths by suicide in European countries.27,28 Similar effects have also been studied in the Japanese population, finding a possible relationship between suicide rate and total annual sunshine, with a higher risk in places with fewer daylight hours.29

Population structures may also be relevant to explain the results obtained. The reduced availability of social and emotional support, shame and isolation, have been linked to higher rates of unhappiness, stress, chronic depression and suicide peak in middle age.

Toxics and alcohol abuseAccording to our analysis, some of the countries in which we found a worse suicide situation (less improvement in trends or even a worsening, as well as high numbers of YPLL as a result of suicide or high rates of suicide among other deaths) are those in which a higher use of toxic use has been observed.

Several studies have shown that alcohol and drug-related disorders are major contributors to increased risk of suicide, aggressive behavior, comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders and interpersonal conflicts.30–32

In terms the geographical distribution of drug abuse, the countries that formerly comprised the Soviet Union are known to have some of the highest rates of alcohol consumption in the world. In contrast, Asian countries have the lowest rates of alcohol consumption, while European and American countries are in between.33 There is some geographical association between high alcohol consumption and high mortality rates and social problems, a striking situation in the Baltic countries34 where significant links with suicide rates have also been found in regions such as Russia.35 On the other hand, in the case of Asian countries, although they do not represent the region with the highest alcohol consumption, their growth rates have been increasing in recent years.36 Although, as we have already mentioned, alcohol is not the only risk factor, it is the only one.

Cultural factorsWe note that Japan and Korea have the highest percentages of YPLL due to suicide among other causes. Changing social and cultural contexts, as in the case of Korea, have been studied as possible underlying risk factors for suicidal behavior.37

Previous studies also refer to a possible “tradition of suicide” in these societies. Some sociologists argue that the “culture of courage” unique to Asian culture contributes to Japan's unusually high suicide rates among industrialized countries.38

On the European continent, factors such as social suffering caused by the post-Soviet transition and difficulties in implementing an effective mental health system inherited from the Soviet Union in the 1990s may influence a higher risk of suicide.30 In the case of Finland, the suicide rate went from the lowest in 1870 to the highest in 1990, as reported by Helliwell39 and Durkheim,40 a more than tenfold increase.41

As reported by Daly et al.,42 “the happiest places, such as Finland, tend to have the highest suicide rates”. The results of this studies suggest that people construct their norms by observing the behavior and outcomes of others. As such, they will tend to judge their own.43

Interventions and health planningNumerous studies have assessed the socio-economic impact of accidents and injuries over time, which has contributed to the development of policies and interventions to reduce and prevent these causes of death.44 In contrast, in the case of suicide, these interventions have not played such a prominent role, even though they are cost-effective and can lead to significant potential cost savings due to averted suicide deaths and reduced disability due to depression.45

Some regions have implemented prevention programs that have proven to be effective and from which conclusions can be drawn that are potentially applicable to other regions. In the case of Denmark, for example, a long-term reduction in suicide rates has been observed since the implementation of various strategies, which have helped to reduce the suicide rate from 38 per 100,000 population in 1980 to 11.4 per 100,000 in 2007.46

European Alliance Against Depression and Australia's Long Term National Health Plan are examples of investment and research in suicide prevention.47,48

On the other hand, the Qungasvik program in Alaska takes a Native cultural approach to suicide and alcohol abuse prevention.49

For all these reasons, WHO has developed The WHO Live Life for policy development and practical guidance for implementing suicide prevention interventions.3

Strengths and limitationsOne of the main strengths of our study is the novel tools used, the YPLL and the CAGR, which allow us to make a detailed analysis of the suicide situation throughout the world and over time.

In addition to the individual study of each country, we have added per capita adjusted data, which allows us to objectively compare the situation between countries.

The main limitation was the lack of data from all countries in the world, as not all of them met the inclusion criteria. On the other hand, it is also important to note that there are many countries where the number of suicides is underreported. This is one of the major challenges in suicide epidemiology worldwide. Furthermore, our analysis of the available epidemiological data does not allow us to draw definitive conclusions about the complex factors involved in suicidal behaviour.

ConclusionsIn our study we found available data for 69 countries, mostly from the European, American and Asian continents. In contrast, data from the African continent is very scarce. It is therefore possible that there are worrying clinical situations that we cannot fully assess.

In the 69 countries surveyed, the data on suicide are not encouraging.

In most countries, the CAGR index for external causes of death shows decreasing figures, indicating improvement. Prevention of most external causes of mortality shows promising data in most countries. However, this is not the case for suicide. Thus, YPLL due to suicide have decreased to a comparatively lesser extent and have even increased in some countries, a very worrying situation that poses many clinical and epidemiological challenges. The highest rate of suicide was found in high-income countries such as Japan, Korea, Finland, Canada or Australia.

For low- and middle-income countries, the results are very disparate. For example, the largest decrease in suicide CAGR was found in El Salvador, while the largest increase was found in the Dominican Republic.

The situation described suggests that the measures implemented so far may not be sufficient to effectively prevent suicide and achieve the goal of the WHO Global Plan of Action for Mental Health, which proposes to halt the increase in suicide rates and attempt to reduce them by 2030.50

FundingThis research was supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III with the support of the European Regional Development Fund (ISCIII JR22/00011; ISCIII PI20/01555; TED2021-131120B-I00), the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (LSRG-1-005-16), the Madrid Regional Government (AGES-3-CM), and the Fundació La Marató TV3 (202226.31).

Authors’ contributionsConceptualization: Jimena María Merayo-Cano, Alejandro Porras-Segovia, Santiago Ovejero and Enrique Baca-García. Data curation: Jimena María Merayo-Cano. Formal and analysis: Jimena María Merayo-Cano and Enrique Baca-García. Investigation and Methodology: Jimena María Merayo-Cano, Alejandro Porras-Segovia and Enrique Baca-García. Supervision: Santiago Ovejero and Enrique Baca-García. Writing – original draft: Jimena María Merayo-Cano and Alejandro Porras-Segovia. Writing – review and editing: Santiago Ovejero and Enrique Baca-García.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

This research was supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III with the support of the European Regional Development Fund (ISCIII JR22/00011; ISCIII PI20/01555; TED2021-131120B-I00), the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (LSRG-1-005-16), the Madrid Regional Government (AGES-3-CM), and the Fundació La Marató TV3 (202226.31).