Losing a patient by suicide may lead to psychological distress and mid/long-term personal and professional consequences for psychiatrists, becoming second victims.

Material and methodsThe validated Spanish version of the Second Victim Experience and Support Tool (SVEST-E) questionnaire and a 30-item questionnaire created ad-hoc was administered online to psychiatrists from all over Spain to evaluate how patient suicide affects mental health professionals.

ResultsTwo hundred ninety-nine psychiatrists participated in the survey, and 256 completed the SVEST-E questionnaire. The results of the SVEST-E questionnaire revealed a negative impact of suicide on emotional and physical domains, although this seemed not to lead to work absenteeism. Most respondents desired peer support from a respected colleague and considered institutional support, although desirable, lacking. Almost 70% of surveyed stated that an employee assistance program providing free counseling to employees outside of work would be desirable. The ad-hoc questionnaire showed that up to 88% of respondents considered some suicides unavoidable, and 76% considered the suicide unexpected. Almost 60% of respondents reported no changes in the approach of patients with suicidal ideation/behavior, after losing a patient. However, up to 76% reported performing more detailed clinical evaluations and notes in the medical record. Up to 13% of respondents considered leaving or changing their job or advancing retirement after losing a patient by suicide.

ConclusionsAfter a patient's suicide, psychiatrists often suffer the feelings of second victim, impacting personal and professional areas. The study results indicate the need for postvention strategies to mitigate the negative impact of patient suicide.

According to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, approximately 700,000 people commit suicide every year.1 Although multiple factors are involved in suicidal behaviors, most suicides are related to psychiatric diseases (depression, substance use, and psychosis, among others).2 Suicides have an enormous and long-lasting impact on families (first victims) and mental healthcare professionals (second victims). The frequency of professionals who experience patient suicide is unknown. However, it is reported that between 31% and 92% of psychiatrists will suffer the suicide of one or more patients during their professional life.3–6

Recent data from the Spanish Institute of Statistics (INE) depicts a worrisome scenario, showing that from 2018 to 2021, suicide rates grew by 6.4%.7 With an increased number of deaths by suicide and suicide attempts, the need for trained professionals that are capable of adequately conducting risk assessments and treatments is mandatory. In addition, these rates highlight the urgent need for postvention guidelines that could support different stakeholders surviving death by suicide.

Losing a patient may cause feelings of being a second victim to mental healthcare providers,8,9 involving psychosomatic and psychological consequences, mainly troubling memories, anxiety, anger, remorse, and distress, among others.10 This impact could even result in severe consequences such as acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder.11 Moreover, effects on second victims may be exacerbated by a lack of organizational support or litigation.9 Apart from the emotional impact, the second victim phenomenon entails a significant economic impact regarding absenteeism, unnecessary prescription derived from increased uncertainty in clinical decision-making, burnout, and loss of professionals due to a turnover increase.12 Finally, costs associated with the loss of reputation and the institution's social image should also be considered.13

Among Spanish health professionals, the second victim experience has been little investigated,13–15 and no data regarding this phenomenon on psychiatrists have been published so far. Previous studies have investigated the second victim experience concerning losing a patient after a medical adverse event, sometimes leading to mala praxis claims. Data from previous studies conducted in Spain showed that when receiving a malpractice claim, up to 80% of the physicians experienced distress, anxiety and depressive symptoms that affect their professional and personal life. Moreover, this data shows a positive correlation between experiencing distressing symptoms and changes in clinical practice.16,17

Understanding the personal and professional impact of patient suicide is crucial to design tailored postvention strategies that effectively assist the recovery process of those severely affected by a patient's loss.18 As suicide rates in Spain increase, it is reasonable to think that more mental health professionals would encounter patients displaying suicidal behavior. In this context, understandably, the discussion has been focused on preventing actions and understanding the individual, societal and economic impact of suicide. However, the burden of suicide on mental health professionals and the need of postvention has received less attention.

Therefore, this study aimed to describe how patient suicide affects Spanish psychiatrists. Specifically, we aim to understand its implications on the emotional and physical domains and the attitudes toward working with patients showing suicidal behavior. In addition, our study aims to shed light on the needs of professionals encountering suicide to propose actions that might reduce its negative impact.

Material and methodsStudy design and participantsThe present study was designed as a survey. Psychiatrists and psychiatry residents were invited to participate by the Spanish Association of Biological Psychiatry (SEPB, Sociedad Española de Psiquiatría Biológica) and were invited to distribute the survey among their colleagues. No other inclusion criteria were requested. Invitation e-mails were sent to SEPB members four times; in April, June, and July 2022. Participants completed the questionnaire through an online platform (Evalandgo) that ensured data anonymity and confidentiality.

InstrumentsAn ad-hoc questionnaire was created and included 30 questions regarding personal information, impact of the suicide on professional life, support received and legal issues. Then, participants completed the validated Spanish version of the Second Victim Experience and Support Tool (SVEST) questionnaire.19,20 The SVEST-E questionnaire includes 36 items grouped in 8 dimensions: psychological distress (4 items), physical distress (4 items), colleague support (4 items), supervisor support (4 items), organizational support (3 items), non-work-related support (2 items), and professional self-efficacy (4 items); two outcome variables: absenteeism (2 items) and turnover intentions (2 items); and one extra dimension: support option (7 items). Items are evaluated with a five-point Likert scale, with scores ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). The seven items assessing “support option” outcomes are also evaluated through a five-point Likert scale, where 1 corresponded to “strongly do not desire” and 5 “strongly desire”. Higher scores are indicative of a greater experience and feeling of second victim.12 The sum of the scores of all dimensions allows obtaining a total score about the feeling of second victim.12 In our sample, Cronbach's alpha of the SVEST was 0.87.

Statistical methodsThe demographic and sociological characteristics of the participants were summarized using descriptive statistics. Variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) or number and percentage.

ResultsParticipant's characteristicsOne thousand five hundred twenty-seven psychiatrists and residents affiliated with the SEPB were invited via e-mail to participate in the survey. Of them, 299 completed at least one of the questionnaires. Around 60% of participants were female and mainly psychiatrists (98%), with 15.32 years of specialization on average. Participants affirmed they had suffered 3.48 suicides during the professional career, on average. Detailed information about demographics and routine clinical practice of participants is shown in Table 1.

Impact of suicide on professional life, support received and legal issuesUp to 88% of respondents considered some suicides unavoidable, and 76% contemplated suicide as an occupational risk (Fig. 1a). When interrogated about the suicide most impacting in their careers, 76% of participants considered the suicide unexpected, although 50% of patients had a history of suicide attempts. Moreover, only 23% of patients were hospitalized at the time of suicide (Fig. 1b).

Regarding the professional impact, 59% of respondents reported no changes in the patient's approach in patients with suicidal ideation/behavior, although up to 76% of them reported performing more detailed clinical evaluations and notes in the medical record. Furthermore, 47% of participants reported using more legal arguments to explain their clinical decisions. Only 5% of respondents stated avoiding treating suicidal patients, although up to 38% reported changes in their clinical decisions, such as increased hospitalization rates in patients with suicidal risk (Fig. 1c).

Only 25% of respondents perceived changes in their ability to establish therapeutic alliance with suicidal patients. However, most respondents (72%) have adjusted their therapeutic achievement expectations into more realistic ones. Only 3% of respondents reported need of time off after the event, with a recovery period of 9.43 days off, on average. In contrast, up to 13% of respondents considered leaving or changing the job or advancing the retirement after losing a patient by suicide (Fig. 1c).

With regard to the support received, only 2% of respondents contacted professional associations. Overall, 59% contacted patient's family/friends after the suicide, and 82% of them stated that this was supportive. The 34% of providers felt fear or rejection from patient's relatives, and only 9% of respondents attended the patient's funeral (Fig. 1d).

Regarding legal issues, 20% of respondents stated being prosecuted after the event, although in 14% of cases, the prosecution was toward the institution. Among professionals involved in prosecution, the majority (70%) reported no changes to more negative perception of the patient's family (Fig. 1e).

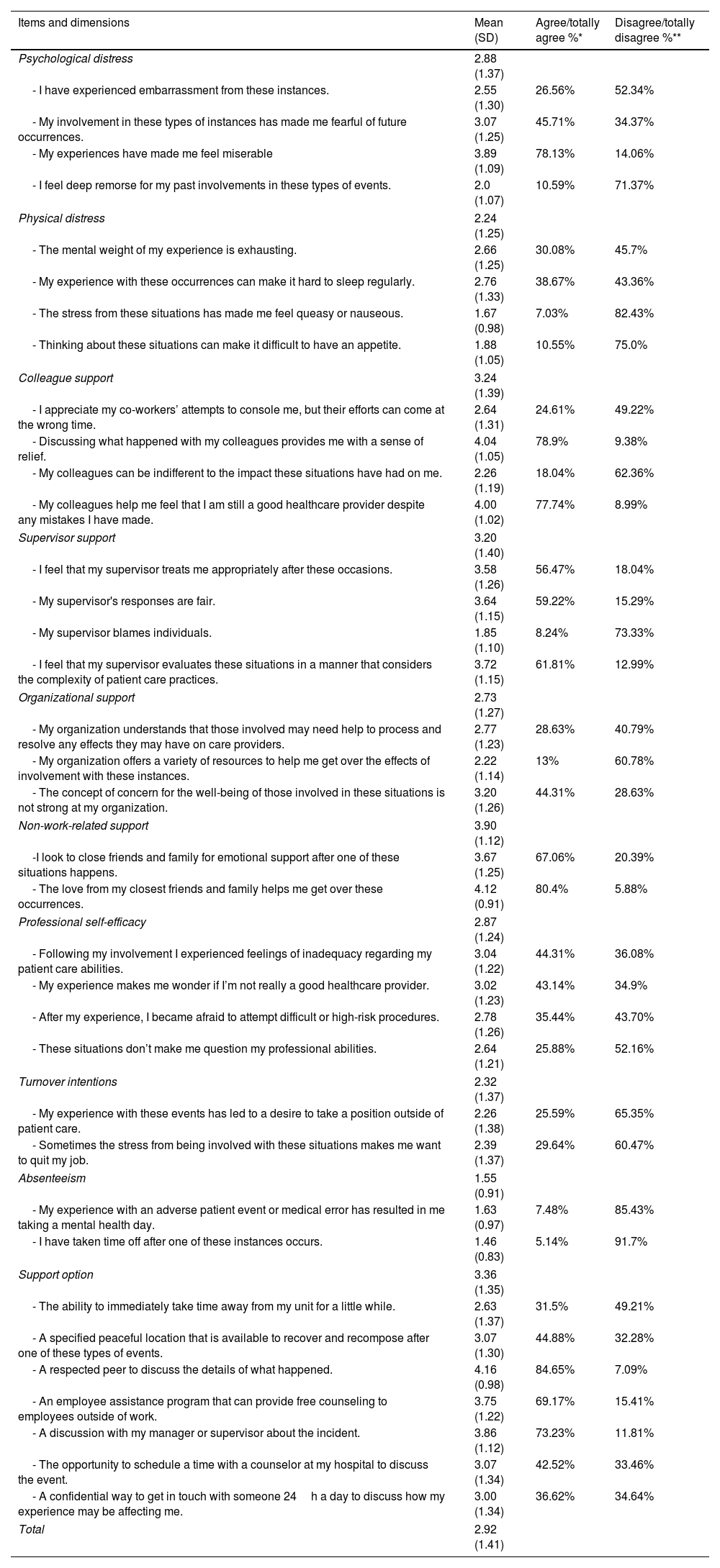

SVEST-E questionnaire resultsThe mean score of the SVEST-E questionnaire for the total sample was 2.92 (SD=1.41). The highest score was obtained on the “non-work-related support” dimension (3.90, SD=1.12), and the lowest on the “absenteeism” outcome (1.55, SD=0.91). The mean (SD), and percentage of agreement for each item of the SVEST-E questionnaire is shown in Table 2.

Questionnaire SVEST-E.

| Items and dimensions | Mean (SD) | Agree/totally agree %* | Disagree/totally disagree %** |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological distress | 2.88 (1.37) | ||

| - I have experienced embarrassment from these instances. | 2.55 (1.30) | 26.56% | 52.34% |

| - My involvement in these types of instances has made me fearful of future occurrences. | 3.07 (1.25) | 45.71% | 34.37% |

| - My experiences have made me feel miserable | 3.89 (1.09) | 78.13% | 14.06% |

| - I feel deep remorse for my past involvements in these types of events. | 2.0 (1.07) | 10.59% | 71.37% |

| Physical distress | 2.24 (1.25) | ||

| - The mental weight of my experience is exhausting. | 2.66 (1.25) | 30.08% | 45.7% |

| - My experience with these occurrences can make it hard to sleep regularly. | 2.76 (1.33) | 38.67% | 43.36% |

| - The stress from these situations has made me feel queasy or nauseous. | 1.67 (0.98) | 7.03% | 82.43% |

| - Thinking about these situations can make it difficult to have an appetite. | 1.88 (1.05) | 10.55% | 75.0% |

| Colleague support | 3.24 (1.39) | ||

| - I appreciate my co-workers’ attempts to console me, but their efforts can come at the wrong time. | 2.64 (1.31) | 24.61% | 49.22% |

| - Discussing what happened with my colleagues provides me with a sense of relief. | 4.04 (1.05) | 78.9% | 9.38% |

| - My colleagues can be indifferent to the impact these situations have had on me. | 2.26 (1.19) | 18.04% | 62.36% |

| - My colleagues help me feel that I am still a good healthcare provider despite any mistakes I have made. | 4.00 (1.02) | 77.74% | 8.99% |

| Supervisor support | 3.20 (1.40) | ||

| - I feel that my supervisor treats me appropriately after these occasions. | 3.58 (1.26) | 56.47% | 18.04% |

| - My supervisor's responses are fair. | 3.64 (1.15) | 59.22% | 15.29% |

| - My supervisor blames individuals. | 1.85 (1.10) | 8.24% | 73.33% |

| - I feel that my supervisor evaluates these situations in a manner that considers the complexity of patient care practices. | 3.72 (1.15) | 61.81% | 12.99% |

| Organizational support | 2.73 (1.27) | ||

| - My organization understands that those involved may need help to process and resolve any effects they may have on care providers. | 2.77 (1.23) | 28.63% | 40.79% |

| - My organization offers a variety of resources to help me get over the effects of involvement with these instances. | 2.22 (1.14) | 13% | 60.78% |

| - The concept of concern for the well-being of those involved in these situations is not strong at my organization. | 3.20 (1.26) | 44.31% | 28.63% |

| Non-work-related support | 3.90 (1.12) | ||

| -I look to close friends and family for emotional support after one of these situations happens. | 3.67 (1.25) | 67.06% | 20.39% |

| - The love from my closest friends and family helps me get over these occurrences. | 4.12 (0.91) | 80.4% | 5.88% |

| Professional self-efficacy | 2.87 (1.24) | ||

| - Following my involvement I experienced feelings of inadequacy regarding my patient care abilities. | 3.04 (1.22) | 44.31% | 36.08% |

| - My experience makes me wonder if I’m not really a good healthcare provider. | 3.02 (1.23) | 43.14% | 34.9% |

| - After my experience, I became afraid to attempt difficult or high-risk procedures. | 2.78 (1.26) | 35.44% | 43.70% |

| - These situations don’t make me question my professional abilities. | 2.64 (1.21) | 25.88% | 52.16% |

| Turnover intentions | 2.32 (1.37) | ||

| - My experience with these events has led to a desire to take a position outside of patient care. | 2.26 (1.38) | 25.59% | 65.35% |

| - Sometimes the stress from being involved with these situations makes me want to quit my job. | 2.39 (1.37) | 29.64% | 60.47% |

| Absenteeism | 1.55 (0.91) | ||

| - My experience with an adverse patient event or medical error has resulted in me taking a mental health day. | 1.63 (0.97) | 7.48% | 85.43% |

| - I have taken time off after one of these instances occurs. | 1.46 (0.83) | 5.14% | 91.7% |

| Support option | 3.36 (1.35) | ||

| - The ability to immediately take time away from my unit for a little while. | 2.63 (1.37) | 31.5% | 49.21% |

| - A specified peaceful location that is available to recover and recompose after one of these types of events. | 3.07 (1.30) | 44.88% | 32.28% |

| - A respected peer to discuss the details of what happened. | 4.16 (0.98) | 84.65% | 7.09% |

| - An employee assistance program that can provide free counseling to employees outside of work. | 3.75 (1.22) | 69.17% | 15.41% |

| - A discussion with my manager or supervisor about the incident. | 3.86 (1.12) | 73.23% | 11.81% |

| - The opportunity to schedule a time with a counselor at my hospital to discuss the event. | 3.07 (1.34) | 42.52% | 33.46% |

| - A confidential way to get in touch with someone 24h a day to discuss how my experience may be affecting me. | 3.00 (1.34) | 36.62% | 34.64% |

| Total | 2.92 (1.41) | ||

SVEST: Second Victim Experience and Support Tool.

Regarding particular items, the one with highest score was “A respected peer to discuss the details of what happened” (4.16, SD=0.98), thus indicating that most participants would desire support from a peer after a patient suicide. The item with the lowest mean was “I have taken time off after one of these instances occurs” (1.46, SD=0.83), indicating no impact on absenteeism (Table 2).

Respondents reported psychological distress, since 78.13% agreed that their experiences have made them feel miserable. However, 71.37% of respondents did not feel deep remorse for their past involvements in these types of events. Regarding physical distress, 82.43% and 75.0% of surveyed disagreed that the stress from these situations has made them feel queasy or nauseous, and that thinking about these situations can make it difficult to have an appetite, items 2.3 and 2.4, respectively (Table 2).

When interrogated about colleague support, around 78% of respondents agreed that discussing what happened with their colleagues provided them with a sense of relief and that their colleagues help them feel that they are still good healthcare providers despite any mistakes they have made. Up to 73.33% of survey respondents did not agree with the item 4.3 “My supervisor blames individuals”, and 80.4% agreed that the love from their closest friends and family helps them get over these occurrences. No consensus was reached on any items regarding organizational support. In addition, up to 84.65% of surveyed agreed that would desire a respected peer to discuss the details of what happened, or a discussion with their manager or supervisor about the incident as support options. Finally, almost 70% of surveyed stated that an employee assistance program that could provide free counseling to employees outside of work would be a desirable support option (Table 2).

Regarding absenteeism, 85.43% of surveyed disagreed that their experience with an adverse patient event or medical error has resulted in them taking a mental health day and 91.7% disagreed that they have taken time off after one of these instances occurred. No consensus was reached on any items regarding turnover intentions (Table 2).

DiscussionThe impact of suicide is far-reaching, affecting relatives, friends, co-workers, health professionals, and institutions. Suicide is avoidable, yet it is estimated that up to 92% of psychiatrists will experience the suicide of a patient.3,4,6,21 Here, we provide data on how Spanish psychiatrists cope with patient suicide. Overall, the results of this survey indicate that losing a patient by suicide negatively impacted most participants, either psychologically or physically. Family, friends, and colleagues’ support was regarded as helpful and essential, whereas most respondents indicated that institutional support was lacking.

To our knowledge, the present study is the first investigation evaluating the second victim phenomena in psychiatry, specifically after an adverse event such as patient suicide. When looking at specific items from the SVEST-E questionnaire, it seems that most participant felt distressed, many of the remained fearful of future consequences and more than a third, experienced some type of sleep disturbance. This data aligns with previous publications, where a significant emotional and psychological impact of patient suicide on mental health professionals was reported.6,22,23 Consistently with other studies,24 our data shows that professional self-efficacy did not seem to be affected, presumably, because many considered suicides as an occupational hazard,25 which is often unavoidable.

Despite suffering psychological and physical distress, few respondents reported turnover intentions nor having taken time off after the event. The few respondents who reported taking time off needed a recovery period of 9.43 days, on average. This could reflect a lower interference of psychological distress on their ability to cope with daily work, which could be related to personal characteristics (e.g., personality traits) or contextual factors (e.g., social support). However, previous evidence in this regard is insufficient to provide a more accurate explanation. Previous data suggest that, in general, psychiatrists are vulnerable to burnout, although they experience lower burnout levels than other mental health professionals.26,27 Future studies could compare absenteeism rates after an adverse event, such as the suicide of a patient, among mental health professionals.

Family and friends were considered the primary source of support, and respondents agreed that the love from their closest friends and family helped them overcome the situation. Additionally, most participants reported that talking to colleagues provided relief and that the supervisor was supportive. This finding is consistent in the literature.28–30 Conversely, most participants perceived receiving no support from the institution, and professional associations were often disregarded as sources of support. Perceiving organizational support is associated with better safety culture and lower emotional exhaustion in second victims; and vice versa, second victims reporting inadequate organization support are significantly more negative in their assessments of safety culture and well-being,31 resulting in a vicious circle. Comparing the impact of patient suicide on groups of professionals who undergo specific support programs with those who would not be an interesting avenue for future research.

Overall, the results of this survey pointed out an unmet need for postvention. Most participants agreed that discussing with a respected peer or supervisor would be helpful. In addition, employee assistance programs providing free counseling outside of work were also considered beneficial. These results are in line with previously published data on second victims.12,20,28–30 Talking to a peer helps normalize the situation, especially because other professionals may have got through similar situations as well. Postvention toolkits are available to students in schools, families, and communities that have suffered the suicide of a loved one. As suggested by our results, postvention actions should include support from colleagues and supervisors after the loss of a patient. We argue that when a patient dies by suicide, institutions should display a set of actions to identify severely distressed professionals and provide them with individualized help. Ensuring a judgment-free and safe environment is essential to diminish feelings of guilt and shame that might emerge as part of the emotional experience of second victims and might restrain professionals from seeking help.32 Although resources to prevent and treat mental health disorders in health professionals are available, active, and specific postvention strategies are still needed. In Spain, some organizational interventions have been designed for second victim assistance33,34; unfortunately, these are not widely spread, and much work still must be done in this area. Continued supervision as part of the routinary professional life should have a pivotal role, and it might serve as an effective prevention strategy for those working with patients at risk.

The results of this study have motivated the creation of a set of webinars in which experienced psychiatrists and family members of patients who died by suicide address several topics, including how to cope with suicide, how to interact with families of patients died by suicide, emotional regulation and prevention, and emotional intelligence. In the future, the impact of such postvention actions should be investigated to design and implement helpful and efficient resources for those who need them. Professionals, institutions, scientific societies, and governments should work collectively to offer support to healthcare providers to improve their well-being and avoid the loss of professionals.

LimitationsThis study has some limitations that should be mentioned. First, the survey was distributed to be completed online among Spanish psychiatrists affiliated with the SEPB. Although they were encouraged to distribute the survey among colleagues, this might have biased the sample. In addition, only 19.5% of the members of the SEPB responded to the survey, which is lower than reported in other studies.35 The online survey burden after COVID might be related to this. Actions to increase the response rate would be needed in future studies. Second, previously published data indicates that demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, profession, age), years of experience, the amount and type of support received, the emotional closeness to the patient have an influence on having more or fewer feelings of second victim.6,19,28 In our sample, no significant correlations between socio-demographics and SVEST-E scores were found. That being said, including a more diverse sample in terms of experience, work-context, and training would have been interesting to observe potential disparities related to them. Third, the responses might be subjected to recall bias. It is possible that respondents who had experienced the suicide of a patient more recently reported more distress than those recalling more distant events. Fourth, the questionnaire did not capture the context in which the respondent works (e.g., private practice, public sector, specialized or primary care), the characteristics of their patients (e.g., age group, diagnosis), or whether they received specialized training in suicide management or supervision. Finally, another possible limitation is the questionnaire length, with 30 questions in the first part and 36 in the second part, which might have caused some bias due to tiredness.

ConclusionsAfter losing a patient, professionals who work in mental healthcare suffer feelings of second victims; in particular, physical and physiological distress. This study highlights the unmet need for institutional support and its importance to the provider's well-being. Efforts should be placed into developing guidelines and specific protocols to identify this phenomenon and develop support tools to overcome these situations. Addressing the need for support for second victims is paramount to improving patient safety and mental health providers’ well-being.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

FundingThis research project has been funded by Janssen-Cilag and the Spanish Society of Psychiatry and Mental Health (SEPSM).

Conflict of interestDr. VP-S has been a consultant to or has received honoraria or grants from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Servier, Medtronic and Exeltis, Novartis, Esteve. Dr. PS has been a consultant to and/or has received honoraria/grants from Adamed, Alter Medica, Angelini Pharma, CIBERSAM, European Commission, Government of the Principality of Asturias, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Plan Nacional Sobre Drogas, and Servier. Dr. DP has received grants and also served as consultant or advisor for Rovi, Angelini, Janssen, Lundbeck and Servier, with no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article. Dr. AG-P has received grants and served as consultant, advisor or CME speaker for the following entities: Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Alter, Angelini, Exeltis, Novartis, Rovi, Takeda, the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (CIBERSAM), the Ministry of Science (Carlos III Institute), the Basque Government, and the European Framework Program of Research. Dr. LG has been a consultant to and/or has received honoraria or grants in the last five years from Adamed, Angelini, Ethypharm Digital Therapy, Janssen-Cilag, Plan Nacional Sobre Drogas and Servier. Dr. MC has been a consultant to and/or has received honoraria or grants from Lundbeck, Otsuka, Janssen and Cassen Recordati.

The rest of the authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank Luzán 5 Health Consulting for their help in the design and execution of the study, and Alba Gómez, PhD for the writing support.

The authors thank the Government of the Principality of Asturias PCTI-2021-2023 IDI/2021/111, the Fundación para la Investigación e Innovación Biosanitaria del Principado de Asturias (FINBA), and Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación. DP thanks the support of Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation/ISCIII/FEDER (PI17/01205 and PI21/01148); the Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement of the Generalitat de Catalunya (2017 SGR 1412); and the CERCA program to the I3PT; the Instituto de Salud Carlos III and the CIBER of Mental Health (CIBERSAM), Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación. This research was supported and funded by project PI19/00236, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) and the European Union; CIBER – Consorcio Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red – (CB/07/09/0010), ISCIII, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación; and the Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement de la Generalitat de Catalunya Government of Catalonia (SGR_00101).