Suicide constitutes a major health concern worldwide, being a significant contributor of death, globally. The diagnosis of a mental disorder has been extensively linked to the varying forms of suicidal ideation and behaviour. The aim of our study was to identify the varying diagnostic profiles in a sample of suicide attempters.

MethodsA sample of 683 adults (71.3% females, 40.10±15.74 years) admitted at a hospital emergency department due to a suicide attempt was recruited. Latent class analysis was used to identify diagnostic profiles and logistic regression to study the relationship between comorbidity profile membership and sociodemographic and clinical variables.

ResultsTwo comorbidity profiles were identified (Class I: low comorbidity class, 71.3% of attempters; Class II: high comorbidity class, 28.7% of attempters). Class I members were featured by the diagnosis of depression and general anxiety disorder, and low comorbidity; by contrast, the high comorbidity profile was characterized by a higher probability of presenting two or more coexisting psychiatric disorders. Class II included more females, younger, with more depressive symptoms and with higher impulsivity levels. Moreover, Class II members showed more severe suicidal ideation, higher number of suicide behaviours and a greater number of previous suicide attempts (p<.01, for all the outcomes), compared to Class I members.

ConclusionsPsychiatric profiles may be considered for treatment provision and personalized psychiatric treatment in suicidal attempters as well as tackle suicide risk.

More than 700,000 people died by suicide in 2019. It means 1.3% of global deaths.1 Despite the huge variability of suicidal behaviour according to age, sex and region,2 the WHO states suicide to be a serious public health concern with global impact.

The latest report published by the WHO showed 36% decrease in the suicide rate compared to the year 2000. Even though, suicide is still the fourth leading cause of death among people between 15 and 29 years old (right below traffic accidents, tuberculosis and interpersonal violence). Besides, prospects on suicide trend are not quite promising. Although the evidence is limited, an increase in stressors derived from pandemics (e.g. Spanish flu, COVID-19) has been observed.3

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and measures to reduce the SARS-CoV-2 virus spread at a national level (e.g., social distancing measures, confinement, national lockdown) may be able to favour certain triggers and risk factors for suicide (e.g., domestic violence, alcohol consumption, social isolation, loneliness).4

A meta-analysis carried out on 113,428 individuals from different countries has found an increase in the prevalence of suicidal ideation, being 11.5% higher during the pandemic times in comparison to previous years.5 One in three people with significant levels of ideation may engage in a suicide attempt within the next 12 months.6 Moreover, over one in ten attempters may engage in a fatal suicidal attempt.7–9 An increasing suicide mortality trend would have therefore been expected. However, studies covering the first months of 2020 did not provide significant evidence on the effect of the pandemic on suicide mortality.10–12 Other studies, using data of 2020, did report an upward trend in the number of suicides since May 2020.3,13–15

Several reasons may be provided in favour of a steady trend of suicide mortality during the first year of pandemic. First, suicidal risk may be mitigated by mental health support strategies and other strategic actions carried out at the governmental level in the countries that launched a national suicide prevention plan.11,16–18 Second, new forms of social connection and engagement have emerged during the pandemic lockdown (both intrafamily and interfamily). Finally, the lack of quality of data collected may be beyond the suicide figures in some countries.19 Nonetheless, it is recommended to monitor the general population, and vulnerable groups (i.e., healthcare workers, people in low-income areas, people with mental health problems) specifically, to see the delayed effects of the pandemic on suicide behaviour and related mortality.4

People with mental health problems may be a key vulnerable population. In low- and middle-income countries, it has been found that around 56% of adults who die by suicide have a mental disorder,20 but in high-income countries, mental disorders may be present in up to 90% of people who die by suicide,1,20 being an important risk factor for suicidal attempts and other suicide behaviours.21–23 Therefore, the excess risk of mortality and disease burden in patients with a mental disorder has become a research and prevention key priority for national health systems.21,24 Depression and alcohol use disorders are the conditions most commonly associated with suicidal behaviour.24–28 Individually, depression has been linked with suicidal ideation and behaviour.24,27,29 Moreover, disorders characterized by anxiety and/or agitation (i.e., post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) and poor impulse control (i.e., conduct disorder and substance use disorders), are strong predictors of suicidal behaviour, particularly unplanned attempts that involves medical severity.26,27,30

Furthermore, the risk of suicidal behaviour may dramatically increase with comorbidity.21,23,27,28,31,32 Comorbidity between disorders constitutes a major challenge in real-world settings, due to complex management and prognosis. The literature supports that the co-occurrence of at least two mental disorders may lead to increased suicidal risk. More concretely, suicidal risk may increase by 3- to 10-times in patients showing comorbid disorders.21,23 This increased risk may be derived from the impact of symptoms, combined with cognitive and/or affective alterations, and side effects from pharmacological treatments on patient's functioning and daily living.27,33,34

Research on the complex interactions between disorders may help characterize suicidal risk. Patients with a recent suicide attempt are especially critical because of the increased risk of suicide repetition and mortality risk.35 The aim of the study was to identify the psychiatric profiles in a sample of adults admitted to a psychiatric emergency ward due to a suicide attempt. We were also interested in studying the relationships of psychiatric profiles with sociodemographic and clinical factors, and suicide behaviour features.

MethodsSampleA sample of 683 adults (71.30% women; M=40.85 years, SD=15.48) from the SURVIVE study was used.36 All patients were recruited at the psychiatric emergency ward from seven public, general, university hospitals across Spain. As an inclusion criterion, patients should have engaged in a suicide attempt within the last 15 days. In addition, all patients should be able to understand the study procedures and signed an informed consent form.

The exclusion criteria were: (1) incapacity to give informed consent, (2) lack of fluency in Spanish and (3) taking part in another clinical study that, in the opinion of the investigator, is likely to interfere with the objectives of the study.

The study was carried out in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki and following the good practice principles. All the protocols from this study have been approved by an ethical committee for human research from each of the recruiting sites.

MeasuresAn ad hoc interview was conducted to collect sociodemographic data: sex, age, marital status and employment status. In addition, the International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)37 was used out to evaluate DSM-5.38 Modules to inspect are: major depressive disorder (MDD), MDD with psychotic features, bipolar disorder type I (BDI), BDI with psychotic features (BDIP), bipolar disorder type II (BDII), other specified and related BD (OSBD), panic disorder (PD), social anxiety disorder (SAD), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), alcohol use disorder (AUD), substance use disorder (SUD), any psychotic disorder (APD), brief psychotic disorder (BPD), substance medication-induced psychotic disorder (IPD), psychotic disorder due to another medical condition (MPD), other specified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder (OSPD), unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder (UPD), anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), binge-eating disorder (BED).

For the assessment of suicidal ideation and behaviour, the Columbia Suicide Rating Scale (C-SSRS) was used.39 The C-SSRS is a clinical scale that assesses and classifies suicidal ideation and behaviour. It also measures presence, severity and intensity of suicidal ideation and types of suicidal behaviour attempts.

The acquired capability for suicide scale-fearlessness about death (ACSS-FAD)40 was also carried out to assess levels of the acquired capability for suicide. ACSS-FAD is a 7-item self-report measure which uses a 5-point Likert scale, from 0 (not at all like me) to 4 (very much like me).

Symptoms of depression and anxiety were evaluated. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)41 was conducted to assess the frequency of depressive symptoms during the last 2 weeks. This questionnaire is completed on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). To assess worry and anxiety symptoms, the general anxiety disorder-7 (GAD-7)42 was used.

The Barratt Impulsivity Scale (BIS-11)43 was conducted to assessed impulsive behaviour. The total score derived from the scale was used in this study.

Data analysisPsychiatric profiles were identified using latent class analysis (LCA).44 LCA constitutes an exploratory, data-driven approach to find the solution with the optimal enumeration of mutually exclusive groups (i.e., classes of psychiatric profile). Clustering variable was the endorsement of diagnosis of each individual Axis 1 disorder (i.e., 27 individual diagnoses; see above), according to DSM-5.38 No covariates were included for latent class solution estimation to prevent from class overestimation.45 Model fit to data was assessed using the following fit indexes: log-likelihood (LliK) value of model convergence, Akaike's information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and entropy R2. Lower values on AIC and BIC, and entropy R2 higher than .70 support feature the model with a better fit to data. Two meaningfulness criteria were also considered to select the model with the optimal class enumeration: the mean of posterior probabilities of being classified into a class should be greater than .70, and a meaningful percentage of cases (at least 5%) within each class.

Logistic (binary or multinomial, depending on the number of identified classes) regression was used to study the relationship between comorbidity profile membership and sociodemographic and clinical factors. The odds ratio (OR) was used as a risk effect estimate. The AIC was used to assess whether the model with covariates explains more outcome variance than an unconstrained model (without covariates). Finally, the relationship between profile membership and categorical suicide behaviour forms (i.e., presence of suicidal ideation and behaviour, and severity of damage from attempt) was studied using the χ2 test; and their intensity by using t tests.

All the analyses were conducted using the R software (package poLCA, lme4, and psych).

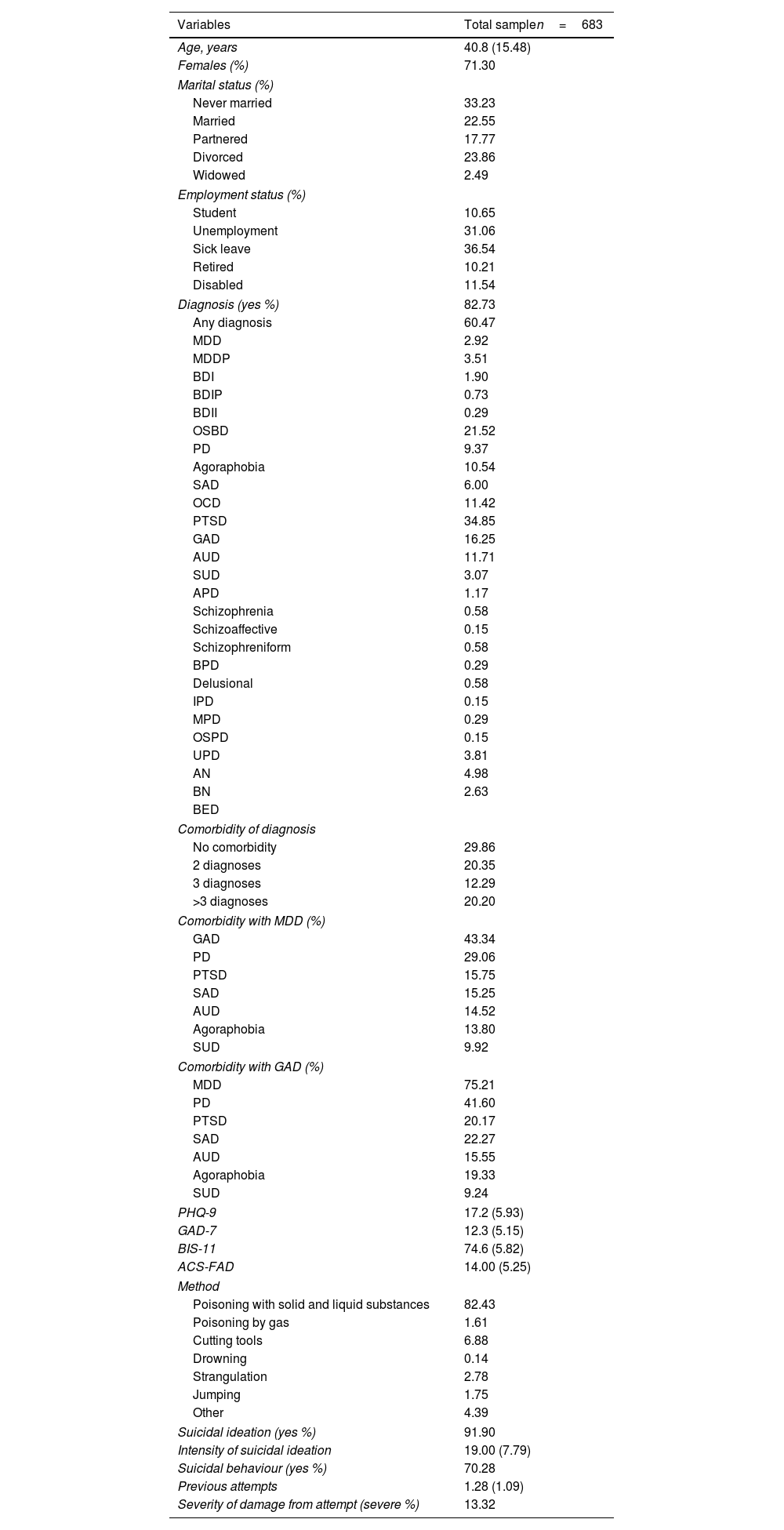

ResultsSociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients are displayed in Table 1. 82.73% of the sample had some diagnosis of mental disorder. 20.20% of these patients had more than three diagnoses. The most common mental disorder in our sample was MDD (60.47%) followed by GAD (34.85%), PD (21.52%) and AUD (16.25%). The comorbidity analysis of the main disorders present in the sample analyzed (presence greater than 5%) showed that 43.34% of the patients with a diagnosis of MDD also had a diagnosis of GAD and in 75.21% of the cases with a diagnosis of GAD, MDD was also diagnosed.

Demographics, and clinical variables.

| Variables | Total samplen=683 |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 40.8 (15.48) |

| Females (%) | 71.30 |

| Marital status (%) | |

| Never married | 33.23 |

| Married | 22.55 |

| Partnered | 17.77 |

| Divorced | 23.86 |

| Widowed | 2.49 |

| Employment status (%) | |

| Student | 10.65 |

| Unemployment | 31.06 |

| Sick leave | 36.54 |

| Retired | 10.21 |

| Disabled | 11.54 |

| Diagnosis (yes %) | 82.73 |

| Any diagnosis | 60.47 |

| MDD | 2.92 |

| MDDP | 3.51 |

| BDI | 1.90 |

| BDIP | 0.73 |

| BDII | 0.29 |

| OSBD | 21.52 |

| PD | 9.37 |

| Agoraphobia | 10.54 |

| SAD | 6.00 |

| OCD | 11.42 |

| PTSD | 34.85 |

| GAD | 16.25 |

| AUD | 11.71 |

| SUD | 3.07 |

| APD | 1.17 |

| Schizophrenia | 0.58 |

| Schizoaffective | 0.15 |

| Schizophreniform | 0.58 |

| BPD | 0.29 |

| Delusional | 0.58 |

| IPD | 0.15 |

| MPD | 0.29 |

| OSPD | 0.15 |

| UPD | 3.81 |

| AN | 4.98 |

| BN | 2.63 |

| BED | |

| Comorbidity of diagnosis | |

| No comorbidity | 29.86 |

| 2 diagnoses | 20.35 |

| 3 diagnoses | 12.29 |

| >3 diagnoses | 20.20 |

| Comorbidity with MDD (%) | |

| GAD | 43.34 |

| PD | 29.06 |

| PTSD | 15.75 |

| SAD | 15.25 |

| AUD | 14.52 |

| Agoraphobia | 13.80 |

| SUD | 9.92 |

| Comorbidity with GAD (%) | |

| MDD | 75.21 |

| PD | 41.60 |

| PTSD | 20.17 |

| SAD | 22.27 |

| AUD | 15.55 |

| Agoraphobia | 19.33 |

| SUD | 9.24 |

| PHQ-9 | 17.2 (5.93) |

| GAD-7 | 12.3 (5.15) |

| BIS-11 | 74.6 (5.82) |

| ACS-FAD | 14.00 (5.25) |

| Method | |

| Poisoning with solid and liquid substances | 82.43 |

| Poisoning by gas | 1.61 |

| Cutting tools | 6.88 |

| Drowning | 0.14 |

| Strangulation | 2.78 |

| Jumping | 1.75 |

| Other | 4.39 |

| Suicidal ideation (yes %) | 91.90 |

| Intensity of suicidal ideation | 19.00 (7.79) |

| Suicidal behaviour (yes %) | 70.28 |

| Previous attempts | 1.28 (1.09) |

| Severity of damage from attempt (severe %) | 13.32 |

Note. Percentage of cases are displayed for dichotomous and categorical variables. Means and standard deviation (between brackets) are displayed for continuous variables.

MDD: major depressive disorder; MDDP: MDD with psychotic features; BDI: bipolar disorder type I; BDIP: BDI with psychotic features; BDII: bipolar disorder type II; OSBD: other specified and related BD; PD: panic disorder; SAD: social anxiety disorder; OCD: obsessive compulsive disorder; PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder; GAD: generalized anxiety disorder; AUD: alcohol use disorder; SUD: substance use disorder; APD: any psychotic disorder; BPD: brief psychotic disorder; IPD: substance_medication-induced psychotic disorder; MPD: psychotic disorder due to another medical condition; OSPD: other specified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder; UPD: unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder; AN: anorexia nervosa; BN: bulimia nervosa; BED: binge-eating disorder; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire; GAD-7: generalized anxiety disorder; BIS-11: Barrat Impulsivity Scale; ACS-FAD: acquired capability for suicide.

Regarding suicide behaviour outcomes, 91.90% of the patients presented suicidal ideation and 70.28% suicidal behaviours (this variable refers to suicidal behaviours assessed 15 days after admission following the onset of suicidal behaviour, as measured by C-SSRS including the presence of non-suicidal self-injurious behaviour, interrupted attempt, aborted attempt, preparatory acts or behaviour since last assessment) and 13.32% of current attempts qualified as severe, in terms of medical damage. The most common method of suicide attempt was self-poisoning (82.43%).

The 2-class solution was retained due to the low levels of AIC and BIC, and acceptable entropy R2 value. Proportion of participants within each class was >5% (see Table 2). Fig. 1 displays the probability of showing each Axis 1 disorder diagnosis according to profile class. Participants in Class I (n=503; 73.64%), so-called low comorbidity class, mainly featured by emotional disorder endorsement, were more likely to show MDD (49.70% of class member), GAD (20.67%), AUD (15.90%) and SUD (12.13%), respectively. The number of diagnosed conditions in Class I members was m=1.24 (SD=0.98).

Latent class model fit. Model comparation table.

| Class 1 | Class 2 | Class 3 | Class 4 | Class 5 | Class 6 | Class 7 | Class 8 | Class 9 | Class 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LliK | −3537.14 | −3271.88 | −3224.89 | −3183.58 | −3183.14 | −3122.99 | −3080.71 | −3109.54 | −3057.24 | −3054.38 |

| AIC | 7128.28 | 6653.76 | 6615.78 | 6589.16 | 6644.28 | 6579.99 | 6551.41 | 6665.08 | 6616.49 | 6666.76 |

| BIC | 7250.50 | 6902.72 | 6991.48 | 7091.60 | 7273.46 | 7335.91 | 7434.08 | 7674.49 | 7752.64 | 7929.65 |

| Entropy R2 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.84 | 0.80 | |

| Percentage of participants (posterior probability) | ||||||||||

| Class 1 | 74 (0.95) | 28 (0.93) | 53 (0.89) | 3 (0.92) | 22 (0.91) | 3 (0.98) | 3 (1) | 15 (0.93) | 61 (0.94) | |

| Class 2 | 26 (0.92) | 71 (0.95) | 19 (0.96) | 26 (0.90) | 1 (0.99) | 13 (0.84) | 1 (0.98) | 12 (0.71) | 2 (1) | |

| Class 3 | <2 (1) | 26 (0.92) | <3 (1) | 6 (0.92) | 56 (0.89) | 11 (0.84) | 1 (0.91) | <2 (1) | ||

| Class 4 | 2 (0.95) | 71 (0.94) | <2 (1) | 1 (0.99) | 65 (0.91) | <2 (1) | 1 (0.95) | |||

| Class 5 | <2 (1) | 69 (0.94) | 6 (0.94) | 1 (0.98) | 1 (0.97) | 11 (0.85) | ||||

| Class 6 | 2 (0.99) | <2 (1) | 18 (0.78) | 9 (0.98) | 3 (0.90) | |||||

| Class 7 | 21 (0.88) | <2 (1) | 58 (0.91) | 3 (1) | ||||||

| Class 8 | <2 (1) | <8 (1) | 7 (0.85) | |||||||

| Class 9 | 2 (0.98) | 12 (0.72) | ||||||||

| Class 10 | 2 (0.93) | |||||||||

Note. LliK: log-likelihood convergence value; AIC: Akaike information criterion; BIC: Bayesian information criterion.

Probability of showing each diagnosis according to profile class.

Note. Each of the red bars represents the percentage of patients according to the class of membership. Class I: low comorbidity class; Class II: high comorbidity class.

MDD: major depressive disorder; MDDP: MDD with psychotic features; BDI: bipolar disorder type I; BDIP: BDI with psychotic features; BDII: bipolar disorder type II; OSBD: other specified and related BD; PD: panic disorder; SAD: social anxiety disorder; OCD: obsessive compulsive disorder; PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder; GAD: generalized anxiety disorder; AUD: alcohol use disorder; SUD: substance use disorder; APD: any psychotic disorder; BPD: brief psychotic disorder; IPD: substance_medication-induced psychotic disorder; MPD: psychotic disorder due to another medical condition; OSPD: other specified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder; UPD: unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder; AN: anorexia nervosa; BN: bulimia nervosa; BED: binge-eating disorder.

Class II (n=180; 26.35%) (so-called high comorbidity class, and featured by a wide amount of endorsed diagnoses) was characterized by patients with high probability of a wide variety of disorder (m=4.49 diagnoses, SD=1.56), namely having MDD (90.55%), GAD (74.44%), other anxiety disorders, PD (65.55%), agoraphobia (35%), SAD (39.44%); PTSD (37.22%), OCD (11.66%), AUD (17.22%), SUD (10.55%) and eating disorders: AN (11.66%), BN (16.11%) and BED (8.8%).

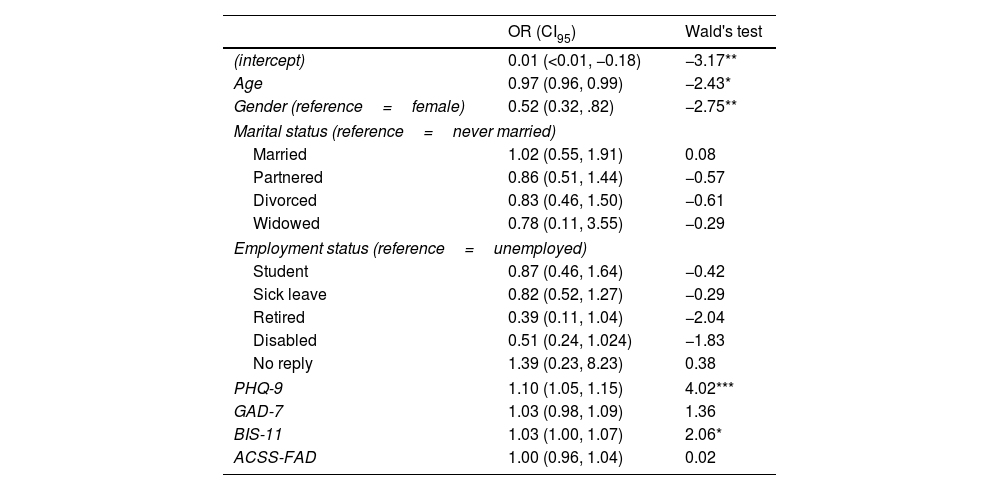

Estimates from logit regression were calculated considering the normative class (Class I). Regarding the logistic regression performed to feature profile classes, the regression model with the predictors showed a better fit (AIC=708.08; R2=.22) than the unconditional model (AIC=789.81), and the model in which only the sociodemographic predictors were included (AIC=755.93). The results indicated that Class II (compared to Class I) were more likely to be female (OR=0.97, p<.01), younger in age (OR=0.52, p<.05), with more depression symptoms (OR=1.10, p<.001) and higher impulsivity (OR=1.03, p<.05) (see Table 3).

Odds ratio and logistic regression loadings of predictors.

| OR (CI95) | Wald's test | |

|---|---|---|

| (intercept) | 0.01 (<0.01, −0.18) | −3.17** |

| Age | 0.97 (0.96, 0.99) | −2.43* |

| Gender (reference=female) | 0.52 (0.32, .82) | −2.75** |

| Marital status (reference=never married) | ||

| Married | 1.02 (0.55, 1.91) | 0.08 |

| Partnered | 0.86 (0.51, 1.44) | −0.57 |

| Divorced | 0.83 (0.46, 1.50) | −0.61 |

| Widowed | 0.78 (0.11, 3.55) | −0.29 |

| Employment status (reference=unemployed) | ||

| Student | 0.87 (0.46, 1.64) | −0.42 |

| Sick leave | 0.82 (0.52, 1.27) | −0.29 |

| Retired | 0.39 (0.11, 1.04) | −2.04 |

| Disabled | 0.51 (0.24, 1.024) | −1.83 |

| No reply | 1.39 (0.23, 8.23) | 0.38 |

| PHQ-9 | 1.10 (1.05, 1.15) | 4.02*** |

| GAD-7 | 1.03 (0.98, 1.09) | 1.36 |

| BIS-11 | 1.03 (1.00, 1.07) | 2.06* |

| ACSS-FAD | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | 0.02 |

Note. Estimates from logit regression were calculated considering the normative class (Class I) as the reference category.

OR: odds ratio; CI: 95% confidence interval.

PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire; GAD-7: generalized anxiety disorder; BIS-11: Barrat Impulsivity Scale; ACSS-FAD: acquired capability for suicide.

In terms of suicidal outcomes, 90.05% of low comorbidity class and 97.20% of high comorbidity class patients presented suicidal ideation during the interview, there being significant differences between both classes (χ2=8.24, df=1, p<.01, Cohen's W=0.11) (see Fig. 2). They also had significant differences in terms of intensity of ideation (t=−4.91, df=389.3, p<.001, Cohen's d=0.38), with a mean severity of Class I, m=18.20 (SD=8.07); and Class II, m=21.16 (SD=6.49).

Percentage of patients with presence of suicidal ideation and behaviour according to class.

Note. The figure shows the percentages of patients by class of belonging who had suicidal ideation, suicidal behaviour and actual attempt severity.

The grey columns belong to Class I (low comorbidity class) and the white columns to Class II (high comorbidity class).

**p<.01; ***p<.001.

Significant differences were also observed in the presence of suicidal behaviours (χ2=26.33, df=1, p<.001, Cohen's W=0.2). Suicidal behaviour was reported by 85.55% of patients belonging to high comorbidity class, compared to 64.81% of low comorbidity class. Moreover, the number of previous attempts was higher in Class II, m=1.69 (SD=1.06) than in Class I, m=1.13 (SD=1.07) (t=−6.18, df=318.01, p<.001, Cohen's d=0.53). No significant differences were observed in medical damage from the attempt (χ2=0.14, df=1, p=.70, Cohen's W=0.2).

DiscussionThe aim of this study was to identify psychiatric profiles in a sample of adults admitted to a psychiatric emergency department due to a suicide attempt and to study the relationships of these profiles with sociodemographic and clinical factors, and characteristics of suicidal behaviour. The main results of our study show the identification of two comorbidity profiles. On the one hand, Class I or low comorbidity class, characterized by the presence of MDD and GAD and Class II or high comorbidity class, characterized by the presence of MDD, GAD and other anxiety disorders, being more likely to have two or more coexisting psychiatric disorders. Compared to the ow comorbidity class, the high comorbidity class members showed more severe suicidal ideation and a higher number of suicide attempts.

82.73% of our sample with attempted suicide had a diagnosis of a mental disorder. This is in line with other studies that have found that a high percentage of patients with a suicide attempt had mental health problems20,25; although as already indicated this is neither a necessary nor a sufficient factor for the presence of suicidal ideation and/or behaviour.

We found two profiles of patients with a suicide attempt, in terms of diagnosed mental disorders. Membership to each class was associated with risk factors and a differential suicidal behaviour. Our results are consistent with the clinical complexity observed among suicide attempters, proposing that the patterns of psychiatric diagnoses and related comorbidities may be a critical factor to be considered in the context of suicide prevention, that may interact with other risk factors, such as impulsivity and depressive symptoms, feature suicide behaviour outcomes.46

The low comorbidity class (73.64% of sample) was featured by a higher prevalence of emotional disorders (i.e., MDD and GAD), and substance use disorders (both AUD and SUD). Previous studies have already described a higher probability of diagnosis of affective disorders among people who attempt suicide.20,25 The high comorbidity class was mainly characterized by the presence of MDD in co-occurrence with a wide variety of mental disorders (i.e., GAD, PD, SAD, PTSD, agoraphobia, AUD, BN, AN, OCD, SUD and BED.). Both classes shared elevated levels of depression and anxiety symptoms, the most common form of mental health problems in suicidal behaviour, that may influence the recovery outcomes and prognosis.30

The high comorbidity class was associated with being a woman, younger, more impulsivity, and more depressive symptoms. More specifically, we observed that the risk of being Class II being female is 50% higher than being male, moreover, with each one-year increase in age, the risk of being Class II decreases by 3% and with each one-point increase in the PHQ-9/BIS-11, the risk of belonging to Class II increases by 3%.

Interestingly, the high comorbidity class was featured in a similar way that Bernanke et al.46 featured patients classified into the so-called stress-responsive thinking class. The authors related this pattern with an impulsive stress response and with childhood trauma history.

Childhood trauma is identified as a risk factor for suicidal behavior6,47,48 and multiple attempts.49 Although childhood trauma has been associated with suicidal behavior6 and repeat suicide attempts,49 it seems to be more impulsive patients.46 We speculate that Class II patients from our study may be also featured by a history of traumatic experiences, as well. Regarding suicidal behaviour outcomes, it is observed that the high comorbidity profile patients had more presence and severity of suicidal ideation and higher number of previous suicide attempts, in line with previous studies stressing higher suicidal risk with mental disorder comorbidity.21,31,49

The presence of suicidal ideation is related to feelings of defeat and entrapment associated with depression.50,51 In addition, patients in the high comorbidity profile showed more depressive symptoms, which could be related with higher presence and severity of suicidal ideation.

In addition, higher number of previous suicide attempts was observed in the high comorbidity class members. Suicide attempt repetition is quite common in patients with comorbid disorders, and it has been observed a history of suicide attempts to be the strongest predictor of future suicidal behaviour.7,31 In this regard, 32.49% of our sample had three or more diagnoses, and other studies have shown that comorbidity of three or more mental disorders increased the risk (OR=3.7) of being a suicide re-attempter almost fourfold.52 Specifically, mood disorder (95% CI [0.13, 0.52], p<0.001), bipolar disorder (95% CI [0.39, 0.56], p<0.001), anxiety (95% CI [0.22, 0.35], p<0.001), post-traumatic stress disorder (95% CI [0.35, 0.57], p<0.001), eating disorder (95% CI [0.07, 0.44], p<0.022) and the presence of psychotic symptoms (95% CI [0.17, 0.51], p<0.001) have been linked to multiple suicide attempts.49

The history of mental problems, particularly depressive episodes and comorbidity between emotional disorders (i.e., depression and anxiety disorders), is proven to be an important factor involved in the transition from the desire for death to suicide attempt engagement.22,30 Furthermore, anxiety disorders and substance use together with the experience of traumatic experiences such as sexual abuse (linked with PTSD), may univocally lead to a higher risk of suicide attempt engagement.30,50 Therefore, individuals in the high comorbidity profile may be at higher risk of future suicide attempts because these patients showed greater levels of risk factors of suicidal behaviour (i.e., more severe suicidal ideation, greater impulsivity, and greater history of suicidal behaviour).6,9,50

Our study had some limitations. First, our study comes from a cross-sectional design, so it was not possible to establish causal relationships between variables that would provide a more decisive explanation on clinical profile of suicide attempters. Moreover, the LCA constitutes an exploratory technique that should only lead to results that should be confirmed in future studies. In addition, although relevant variables in suicidal behaviour were considered, some risk factors, such as childhood trauma or medication, were not studied. Finally, Axis-II diagnoses (i.e., personality disorder diagnoses) were not considered in this study. Future studies should adopt a more comprehensive approach, covering a wider amount of risk factors.

Nevertheless, our study has important clinical implications due to its contribution to personalized psychiatric medicine, as we identified subgroups of individuals with varying psychiatric conditions, patterns of comorbidity and differential relationships with suicide risk factors. In this way, care provision for patients with suicidal behaviour should be more adjusted to the particular needs of each patient, considering their diagnostic profiles. In addition, this study may contribute to develop new therapeutic approaches in line with personalized medicine principles. This is critical for the effectiveness of public policies on suicide prevention.

ConclusionsOur results show that different subtypes of suicide attempters should be considered, according to psychiatric diagnoses. Although suicide is a public health concern and mental pathology is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for suicidal behaviour to occur, its importance should not be underestimated and comorbidity of mental disorders should particularly be regarded as a relevant risk factor for both suicidal ideation and behaviour among attempters. The characterization of these groups is also important for developing new personalized therapeutical approaches that provide valuable insight into the uniqueness of the patient and clinical management in real settings.

FundingThis work was supported by grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), cofounded with ERDF funds: Complutense University of Madrid (PI20/00259), Hospital del Mar (PI19/00236), Universidad de Oviedo, ISPA, SESPA, CIBERSAM (PI19/01027), Hospital Clínico San Carlos (PI19/01256), Hospital Universitario Araba-Santiago, Universidad del País Vasco, CIBERSAM (PI19/00569), La Paz Institute for Health Research (IdiPAZ) (PI19/00941), Hospital Universitario Parc Taulí de Sabadell (PI19/01484), Hospital Clínic, IDIBAPS (PI19/000954) and Hospital Virgen del Rocío de Sevilla (PI19/00685).

IG thanks the support of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MCIN) (PI19/00954) integrated into the Plan Nacional de I+D+I and cofinanced by the ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación y el Fondos Europeos de la Unión Europea (FEDER, FSE, Next Generation EU/Plan de Recuperación Transformación y Resiliencia_PRTR); the Instituto de Salud Carlos III; the CIBER of Mental Health (CIBERSAM); and the Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement (2017 SGR 1365), CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya as well as the Fundació Clínic per la Recerca Biomèdica (Pons Bartran 2022-FRCB_PB1_2022).

Conflict of interestIG has received grants and served as consultant, advisor or CME speaker for the following identities: ADAMED, Angelini, Casen Recordati, Ferrer, Janssen-Cilag, and Lundbeck, Lundbeck-Otsuka, Luye, SEI Healthcare outside the submitted work.

AGP has received grants and served as consultant, advisor or CME speaker for the following entities: Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Alter, Angelini, Exeltis, Novartis, Rovi, Takeda, the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (CIBERSAM), the Ministry of Science (Carlos III Institute), the Basque Government, and the European Framework Programme of Research.

PLP in the last 5 years has received collaborations in the form of registration fees for courses and congresses from the following industries: Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Angelini, Novartis, Rovi, Takeda.

IZ in the last 5 years he has received contributions in the form of registration fees for courses, congresses and speakers from the following industries: Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Angelini, Novartis, Rovi, Takeda.

The following are members of SURVIVE: Natalia Angarita, Irene Canosa, Laura Comendador, Javier Curto, Patricia Díaz-Carracedo, Jennifer Fernández-Fernández, Giovanna Fico, Daniel García, Elena García Ligero, Adriana García Ramos, Natahalia Garrido Torres, Luis Jiménez Treviño, Guillermo Juarez Elvira Lara, Itziar Leal Leturia, María Teresa Muñoz, Beatriz Orgaz, Diego J. Palao, Iván Pérez Díez, Joaquím Punti, Pablo Reguera-Pozuelo, Julia Rider, Pilar A. Sáiz, Elisa Seijo-Zazo, Alba Toll, Mireia Vázquez, Miguel Velasco, Eduard Vieta.

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the research participants, who helped to make this work possible.